Abstract

We developed a multiple time-stepping (MTS) algorithm for multiscale modeling of the dynamics of platelets flowing in viscous blood plasma. This MTS algorithm improves considerably the computational efficiency without significant loss of accuracy. This study of the dynamic properties of flowing platelets employs a combination of the dissipative particle dynamics (DPD) and the coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) methods to describe the dynamic microstructures of deformable platelets in response to extracellular flow-induced stresses. The disparate spatial scales between the two methods are handled by a hybrid force field interface. However, the disparity in temporal scales between the DPD and CGMD that requires time stepping at microseconds and nanoseconds respectively, represents a computational challenge that may become prohibitive. Classical MTS algorithms manage to improve computing efficiency by multi-stepping within DPD or CGMD for up to one order of magnitude of scale differential. In order to handle 3–4 orders of magnitude disparity in the temporal scales between DPD and CGMD, we introduce a new MTS scheme hybridizing DPD and CGMD by utilizing four different time stepping sizes. We advance the fluid system at the largest time step, the fluid-platelet interface at a middle timestep size, and the nonbonded and bonded potentials of the platelet structural system at two smallest timestep sizes. Additionally, we introduce parameters to study the relationship of accuracy versus computational complexities. The numerical experiments demonstrated 3000x reduction in computing time over standard MTS methods for solving the multiscale model. This MTS algorithm establishes a computationally feasible approach for solving a particle-based system at multiple scales for performing efficient multiscale simulations.

Keywords: multiple time stepping, multiscale modeling, coarse-grained molecular dynamics

Introduction

The coagulation cascade of blood may be initiated by flow-induced platelet activation, which prompts clot formation in prosthetic cardiovascular devices and arterial disease processes [1–3]. While platelet activation may be induced by biochemical agonists, shear stresses arising from pathological flow patterns enhance the propensity of platelets to activate and initiate coagulation pathway, leading to thrombosis [4–6]. Quantitatively determining the illusive dynamics and mechanics of platelets in pathological cases can facilitate developing effective treatments [7] and elucidating the platelet initiate processes such as thrombus formation; platelets undergo complex biochemical and morphological transitions during activation, resulting in aggregation and adhesion to blood vessel to form thrombi. In addition to traditional laboratory experiments, numerical simulations augment investigation into understanding of the behavior of platelets at molecular scales [8]. Clearly, a useful model must encapsulate sufficient spatial and temporal details. Fedosov et al [9] describe an elastic model for the membrane with an accurate representation of mechanic properties of red blood cells. Martinez et al [10] conclude that total rigidity of cortex stiffening significantly influenced detachment forces of adherent platelets and cell-membrane internal stresses. These indicate that the membranous viscoelasticity may be a factor for modeling resulting in, unavoidably, more computational complexity. While a complete all-atom molecular dynamics simulation of a biological system can capture the dynamics of platelets at molecular scales [8, 11], this is not practical due to the prohibitive computational resources required [8, 11, 12] as evident by two recent ACM Gordon Bell supercomputing performance records. The first conducted a simulation using 13 trillion grid points in 2013 [13] and the second performed gravitational N-body simulations with one trillion particles in 2012 [14]. These are infinitesimal compared to the atomic modeling of platelets flowing in the viscous fluid flows. A typical platelet could consist of more than 0.7 trillion atoms, roughly estimated by an average mean platelet volume of ~7.1×10−15 L and the possible number of atoms contained in it as compared with a C12 atom with volume of 1.0×10−26 L [15]. Additionally, some atoms interact at diverse scales both in space and time. Thus, we must develop algorithms to model the dynamics of these atoms at corresponding spatiotemporal scales [16–19].

A multiscale particle-based model is proposed to combine the DPD-CGMD methods for modeling the dynamics of platelets flowing in response to extracellular flow-induced stresses [18]. The model adapts the dissipative particle dynamics (DPD) method for describing macroscopic transport of blood plasma in vessels and the coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) method for handling individual platelets. A hybrid force field formulated for establishing a functional interface between the platelet membrane and the surrounding fluid, in which the microstructural changes of platelets may respond to extracellular flow-induced stresses transferred to them. The DPD and CGMD force fields are technically different particle-based coarse-graining methods: the coarse-graining stochastic dynamics and the coarse-graining molecular dynamics [20]. As DPD is the only CGSD method in the work, we use the DPD term for better clarity. First, CGMD forces are conservative [21] but DPD forces depend on relative velocities between particles [22, 23]. Second, the time scale of CGMD is of picoseconds to nanoseconds while that of high-frequency oscillations of covalent bonds is of femtoseconds. However, the time scale of DPD is of microseconds, much slower than those of the constituents in CGMD [24, 25]. Typically, standard time-stepping (STS) algorithms use a single step size which must be the smallest of all time scales involved [21, 26] to gain the needed accuracy at the expenses of significant loss of efficiency.

Admittedly, the STS algorithm can solve the model accurately; however, ignoring the temporal scale differential in a variety of integrators would result in a massive number of redundant computations leading to inefficient use of computational resources. To remedy such deficiency, a variety of multiple time-stepping (MTS) algorithms have been developed for CGMD and for DPD independently. For example, the reversible reference system propagator algorithm (r-RESPA) [27] is widely adopted as the CGMD integrator and it greatly accelerates simulations of systems with multiple times scales and long-ranged forces [27–29]. Second, DPD integrators use the modified velocity Verlet integrator derived from stochastic Trotter formula [23, 30, 31], departing from usual CGMD integrators. Following the modified velocity Verlet integrator, Symeonidis et al [25] integrated the MTS scheme to hybrid DPD models for simulating dilute polymer solutions. It introduced relaxation parameters for optimization with which it gained a 10 folds of efficiency while keeping the accuracy. Jakobsen el al [32] studied several MTS update schemes for a coarse-grained model of a lipid bilayer in water and it reduced considerably the simulation time by optimizing two time scales separately for lipid and solvent within error brackets. MTS algorithms are essential for improving efficiencies of CGMD and DPD [22, 33].

Although multiscale models of cell and tissue dynamics are prevailing [9, 16, 34] and MTS algorithms are established at various scales [25, 27], the temporal coupling is by no means a trivial task. For instance, in the triple decker scheme [34], the time progression in each subdomain is independent and communication of boundary conditions (BC) such as velocity averaging is performed every certain timesteps. The same exchange of boundary information is widely applied to multiscale simulations. Even with rapid advances in raw computing speeds and algorithms, these simulations are still computational expansive [35] and it is necessary to construct models that leverage on accurate understanding of the underlying biomechanics, for maximum utilization of computing resources [22, 24, 33].

Extending our previous efforts on a multiscale model of platelets flowing in viscous blood plasma flows, we develop an integrated MTS algorithm for performing multiscale simulations. We present the force fields and describe the formulation and properties of MTS algorithms for coupling the DPD and CGMD. In this integrated MTS algorithm various parameters are introduced to guide the selection of step sizes for achieving performance optimization. To estimate the quality of the MTS algorithms, we introduce the accuracy vs. speed relationships as functions of step sizes. Extensive numerical experiments were conducted using performance metrics, to measure the relative performances of standard single-scaled time-stepping (STS) algorithm vs. ours. This study is an integral part to a full multiscale particle-based model that studies flow-induced platelet-mediated thrombosis composed of: (i) the spatial interface of the top-scale and bottom-scale methods: DPD and CGMD, whereby the microscale model of platelets allows to continuously undergo microstructural changes in response to extracellular flow-induced stresses [18, 36] and (ii) the temporal interface of the top-scale and bottom-scale integrators in which the step sizes are appropriately specified as multiple scales in order to enhance the computational efficiency while keeping the solutions within predefined error boundaries.

Models

Platelets Flipping in Viscous Flows

In our multiscale model, we consider two scales: (i) the macroscopic/top-scale using DPD for describing viscous fluid flows; and (ii) the microscopic/bottom-scale using CGMD (classical molecular dynamics with reduced degrees of freedom) for describing deformable platelets with internal constituents including membrane, cytoskeleton and cytoplasm. A functional interface hybridizes DPD and CGMD for continued shape changes of flowing platelets in response to extracellular flow-induced stresses.

Top-scale viscous flow model

DPD is employed to simulating human blood flows [23, 37], in which each DPD particle embodies a cluster of atoms or molecules and their collective motion is governed by

| (Equation 1) |

where,

FC, FD and FR are the conservative, dissipative and random forces acting on the particle and FE is the external force exerted to each particle to lead the fluid flow [23, 38]. rij is the inter-particle distance, vij = vi − vj is the relative velocity and eij is a unit vector in the direction ri − rj. ζij is a Gaussian random variable with zero mean and unit variance. α is the maximum inter-particle repulsion [23] given by α = 75kBT/(ρfrc) where ρf is the number of fluid particles. The weight function ωC is set to zero beyond the cutoff length rc and is given by

| (Equation 2) |

Español et al [39] established a relation between γ and σ and weight functions given by σ2 = 2γkBT and ωD = [ωR]2. We construct the wall-driven Couette flow (Figure 1) in a 16×16×8 box (length×height×width in μm) = 2,048 μm3 in volume. The upper and lower vessel walls are moving in opposite directions at a rate of 30 cm/s. Periodic boundary condition (PBC) [21] is imposed along the x-/z-dimension. The no-slip boundary condition between the flow and the vessel is imposed following the work [40]. This general no-slip condition consists of the inclusion of fictitious particles beyond the vessel with reversed velocity to develop an equilibrated shear layer, naturally enforcing zero velocities at the wall plane [40, 41]. Following [23], we work with a number density of the fluid system ρf = 3, i.e., 4,236 particles/μm3. For the flow domain, we have 8.73 million particles.

Figure 1.

The wall-driven Couette flow and the initial position of the platelet model

Bottom-scale deformable platelet model

CGMD is employed to model 3D deformable platelets [18] and structural details are shown in Figure 1. The platelet model comprises of microscale internal constituents including an elastic membrane, a supporting cytoskeleton structure and padding cytoplasm. The model contains 73,036 particles including 19,675 membrane particles (27%), 36,296 cytoskeleton particles (50%) and the remaining 17,065 cytoplasm particles (23%). The initial shape of platelet is a oblate spheroid with semi-major and semi-minor axes of 2.0 and 0.5 μm leading to a total volume of 8.37 μm3. Thus, the number density of the model is 8,722 particles/μm3 and it is roughly twice that of the fluid system. A reduced molecular-scale force field is developed and it includes the bonded interactions (bonds and angles) and the nonbonded interactions (Lennard-Jones (L-J) potential) and given by:

| (Equation 3) |

where

V is the total energy. The first two terms on the right-hand side are the bond and angle components where kb and kθ are the force constants while r0 and θ0 are the equilibrium distance and angle. The last term is the nonbonded L-J potential where ε is the depth of potential well and σ is the characteristic distance at which the inter-particle potential vanishes. The bonded terms exist in membrane and cytoskeleton, and the nonbonded terms are present between any particle pairs within a radius of interaction. Young’s modulus of the membrane model is (1.5±0.6)×103 dyn/cm2 [18]. Young’s modulus of human platelet membrane is reported as (1.7±0.6)×103 dyn/cm2 in [42] (values are mean±standard deviation). For other functional structures, the force constants for cytoskeleton structure are selected strong enough to maintain rigidity and thus to provide support to the ellipsoidal shape of resting platelets. The L-J potential for cytoplasm is selected to preserve the volume of the platelet. Advancing from previous rigid spheroid models [43–48], this model characterizes the proper deforming capability of the membrane and allows us to observe the responsive deformation of platelets and to investigate dynamic stress mapping on the surface membrane resulting from the fluid-platelet interaction.

The top-/bottom-scale spatial interfacing

The DPD-CGMD methods are interfaced on the surface membrane where a hybrid force field is established [18]. Figure 2 shows the schematics of the spatial-interfacing approach. The hybrid force field is defined as:

| (Equation 4) |

where,

Figure 2.

Multiple methods: DPD and CGMD D in the multiscale approach

ε and σ are the characteristic energy and distance parameters in CGMD. Other parameters including γp and σp retain the same definitions as in DPD. All forces are truncated beyond a cutoff radius which defines the length scale in the fluid-platelet contact region [34]. The L-J force ∇U(rij) helps the cytoskeleton-confined shapes and the incompressibility of platelets against the applied stress of circumfluent plasma flow. The dissipative and random force terms maintain the flow local thermodynamic and mechanical properties and exchange momentum to express interactions between the platelet and the surrounding flows. A no-slip boundary condition was applied at the fluid-membrane surface interface. A dissipative or drag force was added to enforce the no-slip boundary condition at the fluid and membrane interface, so the fluid particles are dragged by dissipative forces of membrane particles as they are getting closer to the membrane, mimicking boundary layer mechanism where one layer drags its adjacent layers. The hard-core L-J force simultaneously provides a bounce-back reflection of fluid particles on the membrane (to prevent fluid particles from penetrating through the platelet membrane) with the no-slip achieved by slowing down the fluid particles (by the same repulsive term) as the fluid particles are getting closer to the membrane surface. The magnitude of the L-J force increases to infinity as the distance decreases, guaranteeing that the L-J force be strong enough to slow down and bounce back fluid particles. The parameters for these forces were appropriately selected to preserve the dynamic pr roperties of flowing platelets in shear viscous flows. This complex repulsive-drag force used to achieve the no-slip conditio on at the surface, was used to compute the values of the stresses on the surface of the membrane, following the force virial contribution using the algorithm in [21, 49].

Multiple Time-Stepping Algorithms for Multiscale Modeling

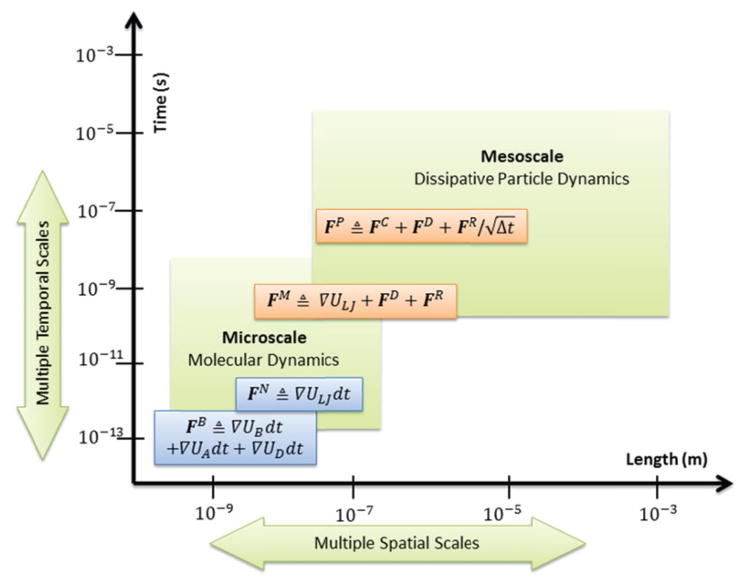

The disparity in the spatial and temporal scales between the CGMD-based platelet and the DPD-based fluid is depicted in Figure 3, where bonded forces FB and nonbonded force FN cover molecular-scale interactions within the platelet. FB consists of bond and angle forces between cytoskeleton particles. FN is the L-J force between cytoplasm and other intra-platelet components including membrane and cytoskeleton. The macroscopic-scale interaction means the DPD force FP for describing the bulk transport of flowing plasma. The mesoscopic hybrid force field FM integrates the conservative force ∇ULJ from the molecular level and the thermostatic forces FD + FR from the macroscopic level and this requires a median time integrator. The bottom-scale CGMD force field is conservative while the top-scale DPD, as a novel thermostatting method [23], considers the additive dissipative and random interactions. FM follows such thermostatting method as a variant of the DPD force field in which the soft conservative potential is replaced with a hard one.

Figure 3.

Multiple spatiotemporal scales in one model

The temporal scales for CGMD and DPD require nanoseconds and microseconds respectively [23, 50]. Standard timesteping (STS) algorithm requires a timestep small enough to resolve fastest motions [51]. Thus, the nanoscale integrator is applied to both top-scale and bottom-scale methods for capturing the dynamics of platelets flowing in viscous blood plasma. However, this significantly increases the unnecessary computation for DPD with fine-grained integrators [23]. Moreover, even for the CGMD, a long-range and low-frequency force can be calculated with a larger time step than a short-range and high-frequency one [29]. To improve the computing efficiency within error boundaries, we must design MTS algorithms for handling the disparity in temporal scales between DPD and CGMD.

MTS for top-scale DPD

In DPD, the forces are stochastic and nonlinear as the dissipative force depends on velocity [23, 25, 39] and, particularly, the conservative force FC(r) in (Equation 1) is similar to that in CGMD. The stochastic of this process disables the previous Euler-type algorithm used in the standard velocity Verlet integrator [52] that requires a velocity-independent force. Thus, a modified velocity Verlet integrator is derived from stochasttic Trotter formula [23, 30, 31]:

| (Equation 5) |

Starting from initial conditions {r(0), v(0)}one computes the position at full-step then a prediction for the new velocity, which is denoted by ṽ, and then computes the force and corrects the velo ocity at the last step. This is a basic predictor-corrector approach in which the velocities, for each time step, are predicted while estimating the force and are corrected at the end. The provisional values of velocities are crucial as s the dissipative force depends on relative velocities of particles. The empirical factor λ accounts for the additive effects of stochastic interactions [23]. If the force is conservative without either dissipative or random terms, λ=0.5 restores the velocity Verlet integrator with O(Δt2).

Symeonidis el al [25] extend a MTS scheme to DPD to simulate a complex fluid with hard/soft potentials using two integrator scales: δt and Δt = n · δt where n is a positive integer. Standard integrator in DPD is subdivided into a multi-rated dynamics of two matters with the hard and soft potentials described by the L-J potential and the soft-repulsive potential, respectively. The soft (or hard) matter employs the soft (or hard) potential so the dynamics is advanced with a larger (or smaller) time-step Δt (or δt). With extension of velocity Verlet integrator, MTS for DPD is summarized in Table 1. In the table, the subscripts h and s correspond to variables for hard and soft potentials. Fh and Fs represent the forces derived for corresponding potentials and λh and λs are relaxation parameters.

Table 1.

The multiple time-stepping algorithm within a 2-level integrator in DPD

| ▶ |

|

Soft potential | |

| ▶ | For l = 0 … n − 1 (δt = Δt/n) | Hard potential | |

| ▶ | set t0 = l · δt, t1 = (l + 1) · δt | Hard potential | |

| ▶ | Hard potential | ||

| ▶ | r(t1) ← r(t0) + δt · ṽ(t1) | Soft/Hard potentials | |

| ▶ | compute Fh[rh(t1), ṽh(t1) | Hard potential | |

| ▶ | Hard potential | ||

| ▶ | compute Fs[rs(Δt), ṽs(Δt) | Soft potential | |

| ▶ |

|

Soft potential |

MTS for bottom-scale CGMD

In CGMD, the reversible reference system propagator algorithm (rRESPA) [27] is widely adopted. Standard integrators in molecular dynamics require evaluating forces at every time step regardless of interaction range, resulting in massive and, sometimes, unnecessary computation. A faster solution is to subdivide the pair forces F(x) into short- and long-ranged components Fs and Fl. The short-ranged force determines the time step δt and the long-ranged uses step size Δt = n · δt where n is usually chosen as a positive integer. Fs includes the bonded forces while Fl the non-bonded forces such as Coulombic potential. rRESPA is based on Trotter expansion of classical Liouville operator [27–29] and the Liouville operator L for a system of N degrees of freedom in Cartesian coordinates is where Γ = {xj, pj} are the position and conjugate momenta of the system, Fj is the force on the jth degree of freedom, and {···, ···} is Poisson bracket of the system. L is a linear Hermitian operator on the space of square integrable functions of Γ [27] so it can be decomposed as iL = iL1 + iL2 where and . Classical time propagator is U(t) = exp(iLt) and the state of the system at time t is Γ(t) = U(t)Γ(0) = eiLt Γ(0) where Γ(0) is the initial state. Trotter expansion yields the velocity Verlet integrator [27, 28]:

| (Equation 6) |

Starting from initial conditions {r(0), v(0)}, one computes the velocity at the half-step then the position at the full step, and completes calculation of the velocity at the second half-step. This velocity Verlet integrator performs better at small time steps than the position Verlet integrator [27] and is used in LAMMPS [53]. With rRESPA,, the MTS algorithm for CGMD [53] is summarized in Table 2. In our platelet model, the bonded force is used in cytoskeleton structure (filamentous bundles) and the nonbonded L-J force is used between cytoplasm particles. These forces act at nanometer scales. The equilibrium bond length for filamentous bundles is 21.3 nm and the equilibrium distance at which the L-J potential for cytoplasm is zero is 71.1 nm [18]. In this case, the bonded and nonbonded forces FB and FN are considered as the short and long range forces Fs and Fl (Table 2), respectively. This yields a separation of short-range bonded and long-range nonbonded forces in the CGMD-based platelet system. In the notation, we follow the traditional terminology for Fl and Fs in expressing MTS algorithms for molecular dynamics (Table 2) [27, 28]. When describing specific MTS schemes, we change to more specific terms FN (CGMD-NB) and FB (CGMD-BD) (Table 3). Recently, novel equations of motions are suggested such as in [54] that showed promising performance for molecular dynamics with large time step without resonant problems [55] and might be useful within CGMD when the framework needs remodeling for the future. This work followed standard Trotter expansion formulas as in [23, 27, 28, 30, 31].

Table 2.

The multiple time-stepping algorithm within a 2-level integrator in CGMD

| ▶ |

|

Long range force | |

| ▶ | For l = 0 … n − 1 (δt = Δt/n) | Short range force | |

| ▶ | set | Short range force | |

| ▶ | Short range force | ||

| ▶ | Long/Short range force | ||

| ▶ | compute Fs[r(t0 + δt)] | Short range force | |

| ▶ | Short range force | ||

| ▶ | compute Fl[r(Δt)] | Long range force | |

| ▶ |

|

Long range force |

Table 3.

Overview of the multiple time-stepping algorithms for the multiscale model

| ▶ | vp ← vp + λp · (Δt/m) · FP | DPD |

| ▶ | For l1 = 0 … K1 − 1 | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | set δt1 ≡ Δt/K1 | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | vm ← vm + λm · (δt1/m) · FM | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | For l2 = 0 … K2 − 1 | CGMD-NB |

| ▶ | set δt2 ≡ δt1/K2 = Δt/(K1 · K2) | CGMD-NB |

| ▶ | vn ← vn + (δt2/2m) · FN | CGMD-NB |

| ▶ | For l3 = 0 … K3 − 1 | CGMD-BD |

| ▶ | set δt ≡ δt3 = δt2/K3 = Δt/(K1 · K2 · K3) | CGMD-BD |

| ▶ | vb ← vb + (δt/2m) · FB | CGMD-BD |

| ▶ | r ← r + δt · v | All Particles |

| ▶ | Communication of positions and velocities. | |

| ▶ | compute FB(r) | CGMD-BD |

| ▶ | Communication of forces. | |

| ▶ | vb ← vb + (δt/2m) · FB | CGMD-BD |

| ▶ | compute FN(r) | CGMD-NB |

| ▶ | Communication of forces. | |

| ▶ | vn ← vn + (δt2/2m) · FN | CGMD-NB |

| ▶ | compute F̃M(r, v) | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | Communication of forces. | |

| ▶ | vm ← vm + (δt1/2m) · (FM + F̃M) | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | FM ← F̃M | DPD-CGMD |

| ▶ | compute F̃P(r, v) | DPD |

| ▶ | Communication of forces. | |

| ▶ | Add external forces to the viscous flow if any. | Add Forces to flow |

| ▶ | vp ← vp + (Δt/2m) · (FP + F̃P) | DPD |

| ▶ | FP ← F̃P | DPD |

The top-/bottom-scale temporal interfacing

MTS algorithms have been widely used in each of CGMD [27–29, 56] and DPD [23, 25, 53] independently and have been extended with the velocity Verlet integrator. Therefore, in our proposed integration of MTS algorithms for the DPD-CGMD model, we decompose the whole integrator process into four levels (Figure 4). The topmost two levels use the scheme in Table 1, referred as DPD-MTS, because both of them employ the DPD thermostatting method. The bottommost two levels use the scheme in Table 2, referred as CGMD-MTS, because both of them employ the conservative potentials. In each of DPD-MTS and CGMD-MTS, the integrator is subdivided into two time scales, one for the soft potential with a larger step size and the other for the hard potential with a smaller step size. Table 3 describes the 4-level integration procedure where communication and external forces are considered. In our multiscale model, “DPD” in the table implies the soft-repulsive, dissipative and random forces between the plasma particles, as well as the external forces applied to the plasma. It is advanced by the DPD-MTS integrator with Δt as defined in Figure 4. “DPD-CGMD” implies the deformable platelet membrane as the contact region between the platelet and the surrounding fluid and it combines the hard-repulsive L-J potential with thermostatting variables, so that it is advanced by DPD-MTS but with a smaller step δt1 = Δt/K1. Wrapped by the membrane are the CGMD-governing intra-platelet constituents and thus CGMD-MTS is used for cytoskeleton and cytoplasm. The cytoskeleton component is for describing the very molecular-scale events such as filopodia formation and the cytoplasm component is for emulating transport of intra-platelet biofluids. The latter structure is grainer than the former resulting in the appropriate integrator choice. The cytoplasmic flow is applied with δt2 = δt1/K2 and the cytoskeleton with the smallest δt3 = δt2/K3.K1, K2 and K3 are all chosen to be integers. Following [23, 25], we use λp = λm = 0.5. The dimensionless and physical units rescaling adopts a dimensionless unit of time equal to 1.2 μs in physical units. Thus, the step size for the DPD integrator is performed at the scale of 10−3 in dimensionless units (i.e., 1.2 ns), and the step size for the CGMD integrator at the scale of 10−7 in dimensionless units (i.e., 120 fs).

Figure 4.

Multiple timestep sizes in the MTS algorithm

Accuracy vs. Speed for Multiscale Simulations

MTS algorithm is usually a matter of trade-offs between speed and accuracy for efficient multiscale simulations. Energy conservation and maintenance of adequate precisions of other measures must be verified while accelerating the computations. We aim to investigate the microscopic shape changes of platelets in response to macroscopic flow-induced stresses. Thus, in measuring numerical solutions we focus on the accuracy of characterizing the hybrid system and the flowing platelets, as well as the accuracy of calculating the dynamic flow-induced stresses on the surface membrane.

For comparative purposes we benchmark all algorithms against the standard time-stepping (STS) algorithm at smallest Δt = 10−7 in its integrator. The largest stepsize for the DPD flow regime is 0.001 which is within critical stepsize [23, 57]. In theoretical accuracy study, “critical stepsize” is the stepsize beyond which the numerical method starts to show pronounced artifacts in [57]. By varying parameters K1, K2 and K3, we produce four representative MTS configurations as shown in Table 4. MTS-L denotes the most liberal integrator in which all timescales are increased up to the top scale while MTS-S represents the most conservative in which the top scale is further fine grained. The other two cases, MTS-M1 and MTS-M2 are the middle levels in which only step sizes for the hybrid force field and nonbonded intra-platelet potentials are adjusted. Through numerical experimentation, the impacts of MTS parameters are examined against STS.

Table 4.

The time steps and configurations for different test cases

| Case Name | Time steps for each scale

|

Configurations 1

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPD | DPD-CGMD | CGMD-NB | CGMD-BD | Δt | K1 | K1 | K3 | |

| MTS-L | 10−3 | 2 × 10−4 | 2 × 10−4 | 2 × 10−4 | 10−3 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| MTS-M1 | 10−3 | 10−5 | 10−6 | 10−7 | 10−3 | 100 | 10 | 10 |

| MTS-M2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−5 | 10−7 | 10−3 | 10 | 10 | 100 |

| MTS-S | 10−4 | 10−4 | 10−6 | 10−7 | 10−4 | 1 | 100 | 10 |

|

| ||||||||

| STS | 10−7 | 10−7 | 10−7 | 10−7 | 10−7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Measures of accuracy

Most measurable variables for our simulations depend on time and they fluctuate around a “mean” value and the long-time average is often considered as a steady state normal value [21]. Time-dependent function ε(υ; t) measures the normalized deviation for variable υ(t) from equilibrium over time (i.e., the time-averaged value v0) is

| (Equation 7) |

where ||·|| is an norm operator. In our model, we directly apply to temperature T, pressure P and total energy Etot of the hybrid system, as well as kinetic energy (kBT)platelet of the platelet where kB is Boltzmann’s constant. This indicator is for assessing the impacts of MTS parameters on the statistical stability of these measures. The dynamic stress distribution on the surface membrane also measures the accuracy of assessing the platelet activation factors. In this, we introduce a more rigorous per-particle comparison between MTS and STS, and design a 3-step procedure as follows: in Step I, the per-particle stress tensor τij(p, t) = [ταβ]3×3 where α and β ∈ x, y, z to generate the 6 time-varying components of symmetric tensor [26, 49]:

| (Equation 8) |

where r1, r2 and F1 and F2 are the positions and resulting pairwise forces of two particles. The first term comes from kinetic energy and the rest computes a scalar virial produced by a group of interacting particles as defined in [49, 58]. Specifically, the second and third terms are from nonbonded and bonded pairwise energy, respectively, where n loops over Np neighboring particles and m loops over Nb bonded particles. The virial theorem routinely computes the volume averaged tensors for a collection of particles and thus the per-particle stress needs to be divided by a per-particle volume to have the correct measure of stress [49, 58]. (Equation 8) is an alternate formula of per-particle stress in CGMD [21, 58]. In Step II, the instantaneous stress tensor is rendered into a scalar τ̂(p, t) as defined in [5, 59]:

| (Equation 9) |

In Step III, the per-particle stress scalars are produced on the surface membrane and the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) is calculated to measure deviations of the per-particle stress scalars between the two systems:

| (Equation 10) |

where Nm is the total number of the membrane particles. τ̂m(p, t) is the stress scalar of particle p at time t through using MTS. Similar to (Equation 7), τ̂0(p, t) is the averaged stress scalar of the same particle over a period of dynamic equilibrium through using STS. RMSD(τ̂, t) evolves with time and it is an indicator for stability of accurately assessing the dynamic stress distributions on the membrane and such an indicator for a MTS algorithm must be bounded when comparing with STS. Finally, integrating RMSD(τ̂, t) with ε(υ; t) yields:

| (Equation 11) |

The numerator is RMSD(τ̂, t) and the denominator is the spatial-averaged magnitude of the per-particle stresses on the surface membrane. Collectively, ε(τ̂; t) indicated the relative deviations of averaged stress τ̂(t) on the membrane.

Measures of speed

The wallclock time of a simulation,

(ts, np) in which ts is the simulated time (for the physical problem) and np is the number of processor cores allows us to define a normalized speed

(ts, np) in which ts is the simulated time (for the physical problem) and np is the number of processor cores allows us to define a normalized speed

(np) as:

(np) as:

| (Equation 12) |

The unit of

(ts, np) is hours and the unit of ts is the dimensionless simulation time unit. Thus,

(ts, np) is hours and the unit of ts is the dimensionless simulation time unit. Thus,

(p) measures the length of simulated time per core-hour. A larger

(p) measures the length of simulated time per core-hour. A larger

(p) means a faster simulation. Speedup of a MTS algorithm is defined as the ratio of the speed of a MTS algorithm over that of a STS algorithm so it refers to how much MTS is faster than STS using the same resources. Parallel efficiency of a parallel program is traditionally defined as:

(p) means a faster simulation. Speedup of a MTS algorithm is defined as the ratio of the speed of a MTS algorithm over that of a STS algorithm so it refers to how much MTS is faster than STS using the same resources. Parallel efficiency of a parallel program is traditionally defined as:

| (Equation 13) |

where

(ts, 1) is the wallclock time of a sequential program and ts defines the problem size. However, this efficiency measure is not conveniently applicable to our program of size far beyond the capability of any single node. To address this issue, we define the efficiency

(ts, 1) is the wallclock time of a sequential program and ts defines the problem size. However, this efficiency measure is not conveniently applicable to our program of size far beyond the capability of any single node. To address this issue, we define the efficiency

(np1, np2) as:

(np1, np2) as:

| (Equation 14) |

where np1 and np2 are the numbers of cores and

(np1, np2) uses the speed

(np1, np2) uses the speed

(np1) as a baseline to measure the speed ratio due to core count difference Δp = np2 − np1. 100% means the perfect efficiency for adding these Δp cores. When np1 is small enough and the program has perfect parallelization on fairly small numbers of cores, then

(np1) as a baseline to measure the speed ratio due to core count difference Δp = np2 − np1. 100% means the perfect efficiency for adding these Δp cores. When np1 is small enough and the program has perfect parallelization on fairly small numbers of cores, then

(np1, np2) asymptotically approaches

(np1, np2) asymptotically approaches

(1, np2), i.e., conventional measures such as parallel efficiency in (Equation 13) and thus this efficiency measure measures scalability more accurately.

(1, np2), i.e., conventional measures such as parallel efficiency in (Equation 13) and thus this efficiency measure measures scalability more accurately.

Results and Discussion

To measure the accuracy vs. speed described earlier, we have performed numerous experiments of platelets flowing in benchmark Couette flows. In our simulations, the base step size for STS is Δt = 10−7 (dimensionless unit). The various MTS parameters are listed in Table 4. The simulations using MTS are compared with those using STS in terms of all selected measures described earlier. The spatial cutoff is set as rc = 1.8 for DPD, rc = 1.6 for DPD-CGMD and rc = 1.0 for CGMD. For our experiments, the system must go through a lengthy equilibration process before the plasma laminar flow is stably reproduced and results are collected.

The empirical selection of the larger step size in MTS is up to a multiplier of 10 of the well-established step size in STS and limited by the simulation stability. Symeonidis et al [25] use a multiplier of 10 in the time-staggered DPD model and the multiplier is smaller in CGMD involving the short- and long-ranged forces [28, 51]. However, in our model, the disparity in temporal scales between CGMD and DPD intrinsically poses a great gap, clearly mandating to perform such multiscale simulation more efficiently in order to overcome the computational challenge. For a further analysis of computational feasibility within certain error boundaries, two groups of measures, chaotic (sensitive to MTS parameters) and non-chaotic (insensitive) measures [33] are examined.

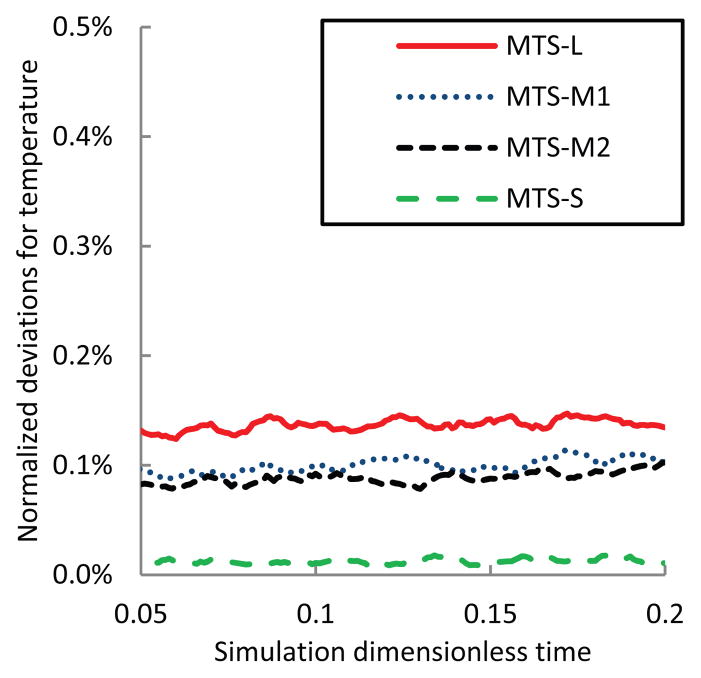

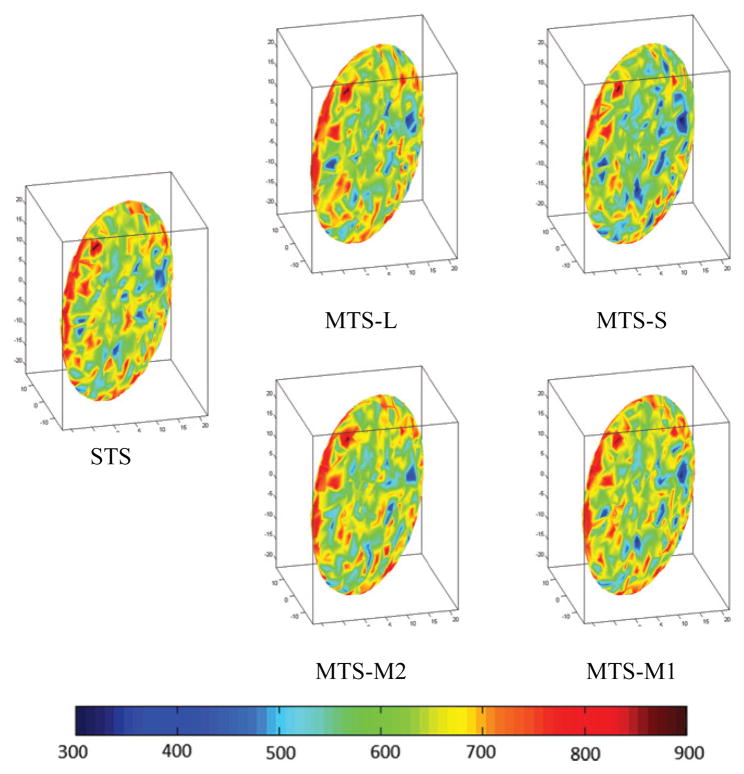

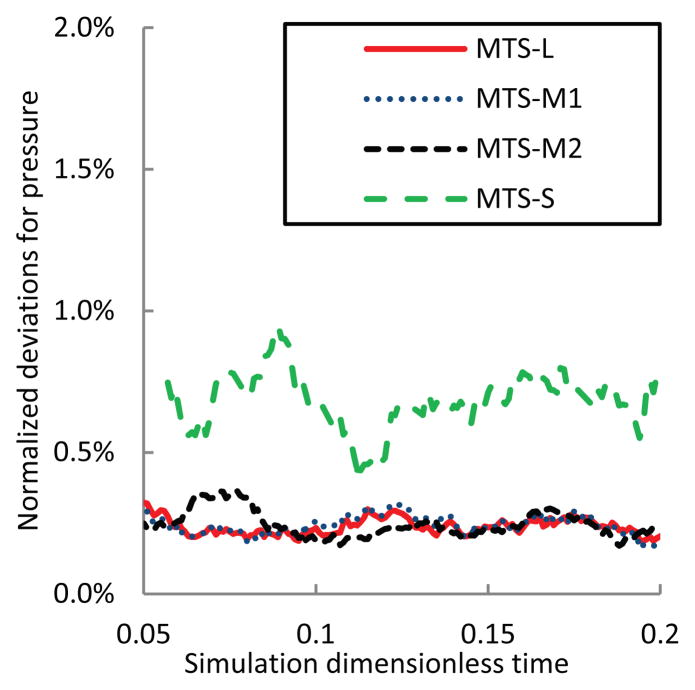

Analysis of Accuracy

Figure 5 to Figure 7 show the evolution of normalized deviations for temperature T, the pressure P and total energy Etot of the hybrid system, respectively. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the evolution of normalized deviations for kinetic energy of the platelet and dynamic stress distributions on the surface membrane, respectively. In all figures, ε(υ; t) (as defined in (Equation 7) is plotted as a function of the dimensionless time t where v takes one of these measures. Mean values and standard deviations of these measures are present in Table 5 for comparisons. Furthermore, Figure 10 shows evolution of RMSD values for flow-induced stresses on the surface membrane by comparing with STS and Figure 11 illustrates 3D stress distributions in a color contour-magnitude diagram. Figure 12 illustrates the trajectories of platelet flipping using MTS-L and compare with the Jeffery’s orbit that is often viewed as a reference point [40, 43, 60].

Figure 5.

ε(T, t): normalized deviations for temperatures T of the system over time

Figure 7.

ε(Etot, t): normalized deviations for total energy Etot of the system over time

Figure 8.

ε((KBT)platelet, t): normalized deviations for kinetic energy of single platelet over time

Figure 9.

ε(τ̂, t): normalized deviations for stress distributions on the membrane over time

Table 5.

Accuracy and speedup comparisons for different MTS parameters

| Metrics for Accuracy and Speed | MTS test cases

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTS-L | MTS-M1 | MTS-M2 | MTS-S | |

| Normalized deviation for temperature: ε(T, t) | (0.136 ± 0.012) % | (0.099 ± 0.013) % | (0.088 ± 0.012) % | (0.012 ± 0.009 %) |

| Normalized deviation for pressure: ε(P, t) | (0.245 ± 0.183) % | (0.247 ± 0.187) % | (0.247 ± 0.175) % | (0.706 ± 0.552) % |

| Normalized deviation for total energy: ε(Etot, t) | (0.144 ± 0.001) % | (0.142 ± 0.001) % | (0.143 ± 0.001) % | (0.148 ± 0.001) % |

|

| ||||

| Normalized deviation for kinetic energy of platelet: ε(KBT, t) | (25.15 ± 2.12) % | (16.96 ± 2.60) % | (15.36 ± 2.34) % | (0.303 ± 0.177) % |

| Normalized deviation for the stress distribution: ε(τ̂, t) | (15.22 ± 0.11) % | (15.6 ± 0.10) % | (15.03 ± 0.09) % | (12.53 ± 0.11) % |

|

| ||||

| Parallel speed (simulated time per core-hour) | 5.58 × 10−5 | 1.53 × 10−7 | 2.00 × 10−7 | 1.56 × 10−7 |

| Speedup (ratio of MTS speed over STS speed) | 2682.1 | 7.3 | 9.6 | 7.5 |

| Parallel efficiency (%) | 51 % | 47 % | 52 % | 45% |

Note: (i) The values for normalized deviations are represented as (mean±standard deviation). (ii) Parallel performance metrics are compared based on experiments using 600 cores.

Figure 10.

Evolution of RMSD for stress distributions on the membrane over time

Figure 11.

The dynamic stress distributions on the surface membrane using STS and MTS

Figure 12.

Change of rotational angles of the platelet using MTS-L, comparing with the Jeffery’s orbit (Analytical)

Among these measures, temperature and total energy of the hybrid system behave the most stable as their normalized deviations are consistently < 0.2%. This verifies that selected MTS parameters maintained energy conservation from the system point of view. Pressure is another non-chaotic measure since it has achieved > 95% in accuracy, though its normalized deviations are larger than those of T and Etot. Obviously, there is no a clear-cut distinction between chaotic and non-chaotic measures and the assignment depends on MTS parameters. Thus, within selected MTS parameters and simulation period, macroscopic measures including temperature, pressure and total energy could be viewed as non-chaotic.

Comparatively, kinetic energy of the platelet is fairly sensitive to MTS parameters. The conservative scheme, MTS-S allowed a negligible deviation from STS but the aggressive scheme, MTS-L caused >25% loss of accuracy. Two middle schemes, MTS-M1 and MTS-M2 posed a similar loss of accuracy between 15% and 20%. An advantage of four MTS schemes is that they all appear a bounded error range, thus avoiding propagation of resultant errors. This advantage offers an alternative way towards a computationally feasible simulation for large-scale time-consuming simulations, within certain error boundaries. Using MTS-L the trajectory of flipping platelets was consistent with Jeffery’s orbit (Figure 12).

Finally, the dynamic stress distributions on the surface membrane are sensitive to MTS parameters but they are not as chaotic as the kinetic energy of the platelet. The loss of accuracy remains at ~15 % and it depends more on the choice of the DPD step size than the choice of other parameters. That is because: (a) MTS-L, MTS-M1 and MTS-M2 used the same step size Δt = 10−3 for DPD and they obtained a similar loss of accuracy. (b) Only MTS-S used Δt = 10−4 and increased the accuracy by >2%. Figure 9 demonstrates that the propagation of resultant errors was prevented within 16%. Figure 10 clearly reaffirms the absolute error boundaries of RMSD values. In an intuitive perspective, the visual representation of the resultant stresses acting on the platelet surface membrane is depicted in Figure 11 for comparing the effect of the different integrators on the resultant stress distribution.

We conclude that in MTS, the macroscopic measures such as T, P and Etot are non-chaotic while the kinetic energy of the platelet and the dynamic stress distributions on the surface membranes are chaotic. These experiments demonstrated that (i) the microscopic measures for single platelets are more sensitive to MTS parameters than the macroscopic measures for the hybrid system. Specifically, the bulk transport of viscous fluid flows can safely advance with a larger step size and the study of microstructural changes of flowing platelets requires a smaller step size. (ii) Within the simulated period and selected step sizes, the errors do not propagate.

In addition to the simple scheme for integrating the DPD flow regime [23], there proposed many integrator variants [22, 57, 61] that allow larger timestep sizes for accurate stochastic dynamics. Though the impact of CGMD MTS scheme dominates in this work with the goal of describing platelets dynamics in flowing blood plasma, one may extend other DPD MTS techniques in molecular modeling such as for complex fluids and polymers [54, 57].

Analysis of Speed

There is a significant improvement in computing efficiency, though some measures showed somewhat chaotic behavior. Figure 13 presents absolute speeds of simulations using MTS and STS. Figure 14 shows speedups of MTS algorithms by comparing to STS. Figure 15 demonstrates parallel efficiencies of MTS and STS. Table 5 presents the performance of these MTS algorithms.

Figure 13.

Parallel speeds

(p) vs. various processor cores p for the non-MTS and MTS solvers (A base 10 logarithmic scale for the vertical axis)

(p) vs. various processor cores p for the non-MTS and MTS solvers (A base 10 logarithmic scale for the vertical axis)

Figure 14.

Speedups of MTS algorithms over the STS algorithm (A base 10 logarithmic scale for the vertical axis)

Figure 15.

The parallel efficiencies

(10, p2) versus various processor cores p2 for the non-MTS and MTS solvers

(10, p2) versus various processor cores p2 for the non-MTS and MTS solvers

In terms of absolute speeds, MTS-M1, MTS-M2 and MTS-S are roughly 10-fold faster than STS and MTS-L, achieving about 2000~3000 reduction in computation time. The timing records presented in Figure 13, indicate that for the computational challenge of simulating one millisecond multiscale phenomena of platelets flowing in viscous fluid flow, STS requires 26 years using 600 cores, where using the same resources MTS requires only ~3.5 days. MTS algorithms offered an opportunity of simulating the molecular-scale mechanisms of deformable platelets flowing in the viscous fluid flows within affordable computing demands.

Figure 14 reiterates the constant effectiveness of MTS algorithms at a variety of computing system sizes. As the number of cores increases, communication is becoming a more dominant factor of limiting the scalability than computation. Thus, the speedups of MTS-L over STS decreased from >4000 to ~2000 while the parallel efficiencies decreased dramatically, as illustrated in Figure 15. Figure 16 compares the percentiles of communication and computation for MTS-L and STS. The results obviously demonstrate that MTS-L is effective at reducing the computation but it poses higher demands on communication than STS does. The performance analysis clearly indicated that a powerful communication system is quite important for improving the performance of multiscale modeling using MTS [12, 62].

Figure 16.

Percentiles of computation (Compt.) and communication (Comm.) over the total running time vs. the number of cores for the STS and MTS-L integrators

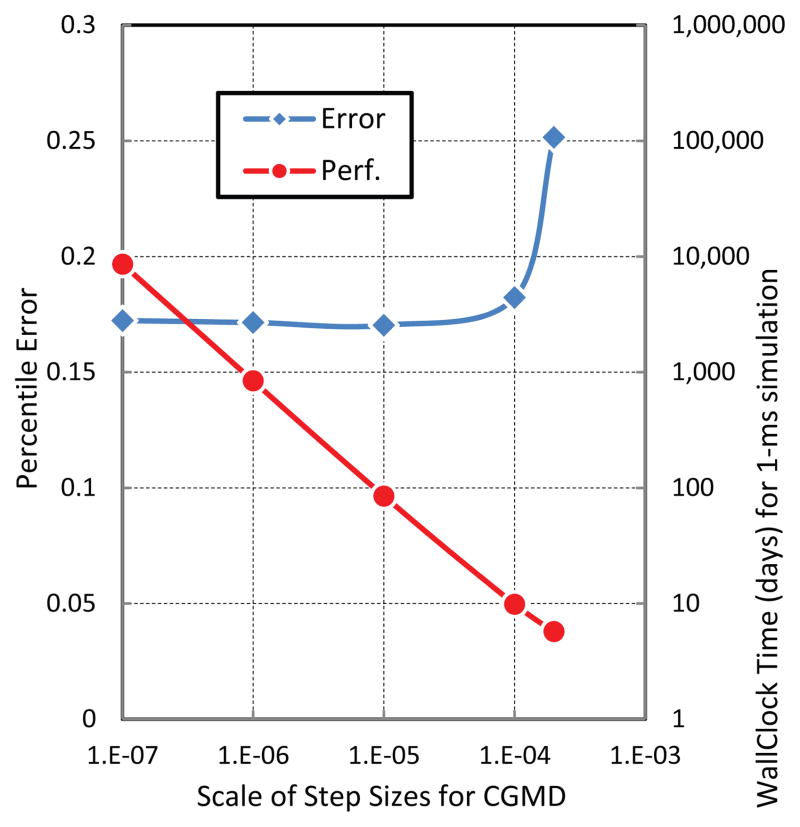

Accuracy vs. Speed for Efficient Multiscale Simulations

Accuracy analysis indicated that, as a measure, the kinetic energy of the platelet system is most chaotic. Analyzing the speed, we realized that the step sizes for CGMD and DPD significantly impacted the computational performance. These observations inspired us to seek a balance between accuracy and speed. In our experiments, we use normalized deviations of kinetic energy of the single platelet as the criterion of accuracy, terming it as the percentile error. A smaller percentile error usually results from a more fine-grained integrator. Additionally, we use the wallclock time (in days) to complete a 1-ms simulated time as the criterion of speed. Our computer has 300 cores. We start with step size for CGMD at 10−7 and vary the step sizes for DPD as shown in Figure 17. We observed that: (a) when the step sizes for DPD increased from 10−7 to 10−5, the speed considerably improved; (b) when the step size for DPD is between 10−5 and 10−3, both the accuracy and speed curves reached a plateau. The percentile error was within 20%, though DPD advanced with a nanoscale step size (Δt = 10−3). Following that, we continued to use the step size 10−3 for DPD and then varied the step sizes for CGMD as shown in Figure 18. We observed that: (c) increasing the step sizes for CGMD caused an obvious performance gain. However, (d) there was a critical point for the accuracy: when the step size for CGMD was close to 10−3, the accuracy quickly deteriorated. These experiments suggest that a nanoscale integrator for coarse-grained stochastic dynamics (Δt ~ 1.2 ns) and a sub-nanoscale integrator for coarse-grained molecular dynamics (Δt ~ 0.12 ns) constitute an optimal combination for accelerating the simulation speed while keeping the percentile error within 20%. These experiments demonstrated that appropriate choice of MTS parameters considerably improve the computational efficiency without a significant loss of accuracy, thus establishing a computationally feasible approach for solving a particle-based system at multiple scales for performing efficient multiscale simulations. The MTS optimization scheme developed and presented herein, tunes a multiple timesteping algorithm for combined DPD-CGMD simulations, which we have applied to the modeling of platelets dynamics in flowing blood plasma. This approach can be employed in any application using such a combined scheme. Generally, the top-scale method of such scheme could advance with much larger step sizes than the bottom-scale method and the spatial-interface between two scales should then adopt a corresponding middle step size. An optimal MTS scheme could be obtained for keeping accuracy of simulating bottom-scale within certain error boundaries.

Figure 17.

Percentile error and wallclock time (in days) for 1-ms simulation vs. different scales of step sizes for DPD in which the CGMD is integrated at 10−7

Figure 18.

Percentile error and wallclock time (in days) for 1-ms simulation vs. different scales of step sizes for CGMD in which the DPD is integrated at 10−3

Conclusions

This paper presents an integrated multiple time-stepping (MTS) algorithm to solve a multiscale model of the dynamics of platelets flowing in viscous blood flow. The MTS algorithm proposes a multi-level integration scheme, allowing an optimization procedure for seeking a faster performer within certain error boundaries. The results demonstrated that the microscopic measures for single platelets are more sensitive to the MTS parameters than the macroscopic measures for the hybrid system; and the error propagation prevented in all cases studied. The results reaffirms that a separation of temporal scales in MTS considerably improves the efficiency of utilizing parallel computing resources, as compared to conventional single-scale methods in which considerable time is wasted conducting massive unnecessary computations (for example, completing 1-ms multiscale simulation of a 10-million particle system is reduced from 2.6 years to 3.5 days only). This work establishes a computationally feasible approach for solving large-scale particle-based systems at multiple scales for performing efficient multiscale simulations. Integrated MTS algorithms such as the one presented in the current work are essential for achieving full multiscale particle-based modeling of complex physiological flows, e.g., flow-induced platelet-mediated thrombosis, etc. Using MTS, we have achieved a dramatic reduction of the modeling time for system sizes and simulation times that are relevant to multiscale phenomena such as thrombosis formation. By developing computationally feasible and efficient approaches, such challenging simulations of molecular biomechanics at multiple scales are brought within the reach of current high-performance computing resources.

Figure 6.

ε(P, t): normalized deviations for pressures P of the system over time

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grants from the National Institute of Health: NHLBI R21 HL096930-01A2 (DB) and NIBIB Quantum Award Implementation Phase II-U01 EB012487-0 (DB). This research utilized computing resources at the National Supercomputing Center in Jinan, China, under the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2012BAH09B03).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bluestein D, Yin W, Affeld K, Jesty J. Flow-induced platelet activation in mechanical heart valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004 May;13:501–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin W, Alemu Y, Affeld K, Jesty J, Bluestein D. Flow-induced platelet activation in bileaflet and monoleaflet mechanical heart valves. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004 Aug;32:1058–66. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000036642.21895.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsheikh-Ali AA, Kitsios GD, Balk EM, Lau J, Ip S. The Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque: Scope of the Literature. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Sep 21;153:387–W149. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-6-201009210-00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien JR, Salmon GP. An independent haemostatic mechanism: shear induced platelet aggregation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1990;281:287–96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3806-6_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alemu Y, Bluestein D. Flow-induced platelet activation and damage accumulation in a mechanical heart valve: numerical studies. Artif Organs. 2007 Sep;31:677–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroll MH, Hellums JD, McIntire LV, Schafer AI, Moake JL. Platelets and shear stress. Blood. 1996 Sep 1;88:1525–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girdhar G, Xenos M, Alemu Y, Chiu WC, Lynch BE, Jesty J, Einav S, Slepian MJ, Bluestein D. Device thrombogenicity emulation: a novel method for optimizing mechanical circulatory support device thromboresistance. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dror RO, Dirks RM, Grossman JP, Xu H, Shaw DE. Biomolecular simulation: a computational microscope for molecular biology. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:429–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedosov DA, Caswell B, Karniadakis GE. A Multiscale Red Blood Cell Model with Accurate Mechanics, Rheology, and Dynamics. Biophysical journal. 2010;98:2215–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez EJ, Lanir Y, Einav S. Effects of contact-induced membrane stiffening on platelet adhesion. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2004 Mar;2:157–67. doi: 10.1007/s10237-003-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Y, Zhang P, Marques C, Powell R, Zhang L. Analysis of Linpack and power efficiencies of the world’s TOP500 supercomputers. Parallel Computing. 2013;39:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossinelli D, Hejazialhosseini B, Hadjidoukas P, Bekas C, Curioni A, Bertsch A, Futral S, Schmidt SJ, Adams NA, Koumoutsakos P. 11 PFLOP/s simulations of cloud cavitation collapse. presented at the Proceedings of SC13: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis; Denver, Colorado. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiyama T, Nitadori K, Makino J. 4.45 Pflops astrophysical N-body simulation on K computer: the gravitational trillion-body problem. presented at the Proceedings of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis; Salt Lake City, Utah. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesnutt JKW, Han H-C. Effect of red blood cells on platelet activation and thrombus formation in tortuous arterioles. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 2013 Dec 3;1 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2013.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi T, Ishikawa T, Imai Y, Matsuki N, Xenos M, Deng Y, Bluestein D. Particle-based methods for multiscale modeling of blood flow in the circulation and in devices: challenges and future directions. Sixth International Bio-Fluid Mechanics Symposium and Workshop March 28–30, 2008 Pasadena, California. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010 Mar;38:1225–35. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9904-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarty J, Lyubimov IY, Guenza MG. Multiscale Modeling of Coarse-Grained Macromolecular Liquids. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009 Sep 03;113:11876–11886. doi: 10.1021/jp905071w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang P, Gao C, Zhang N, Slepian M, Deng Y, Bluestein D. Multiscale Particle-Based Modeling of Flowing Platelets in Blood Plasma Using Dissipative Particle Dynamics and Coarse Grained Molecular Dynamics. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering. 2014 Sep 04;:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang N, Zhang P, Kang W, Bluestein D, Deng Y. Parameterizing the Morse potential for coarse-grained modeling of blood plasma. Journal of Computational Physics. 2014;257(Part A):726–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2013.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padding JT, Briels WJ. Systematic coarse-graining of the dynamics of entangled polymer melts: the road from chemistry to rheology. J Phys Condens Matter. 2011 Jun 15;23:233101. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/23/23/233101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen MP, Tildesley DJ. Computer simulation of liquids. Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besold G, Vattulainen II, Karttunen M, Polson JM. Towards better integrators for dissipative particle dynamics simulations. Phys Rev E Stat Phys Plasmas Fluids Relat Interdiscip Topics. 2000 Dec;62:R7611–4. doi: 10.1103/physreve.62.r7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groot R, Warren P. Dissipative particle dynamics: Bridging the gap between atomistic and mesoscopic simulation. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1997;107:4423–4435. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vattulainen I, Karttunen M, Besold G, Polson JM. Integration schemes for dissipative particle dynamics simulations: From softly interacting systems towards hybrid models. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2002;116:3967. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Symeonidis V, Karniadakis GE. A family of time-staggered schemes for integrating hybrid DPD models for polymers: Algorithms and applications. Journal of Computational Physics. 2006;218:82–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plimpton S. Fast Parallel Algorithms for Short-Range Molecular-Dynamics. Journal of Computational Physics. 1995 Mar 1;117:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuckerman M, Berne BJ, Martyna GJ. Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1992;97:1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ, Martyna GJ. Molecular-Dynamics Algorithm for Multiple Time Scales - Systems with Long-Range Forces. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1991 May 15;94:6811–6815. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuckerman ME, Martyna GJ, Berne BJ. Molecular-Dynamics Algorithm for Condensed Systems with Multiple Time Scales. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1990 Jul 15;93:1287–1291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thalmann F, Farago J. Trotter derivation of algorithms for Brownian and dissipative particle dynamics. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2007 Sep 28;127 doi: 10.1063/1.2764481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano M, De Fabritiis G, Espanol P, Coveney PV. A stochastic Trotter integration scheme for dissipative particle dynamics. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation. 2006 Sep 9;72:190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakobsen AF, Besold G, Mouritsen OG. Multiple time step update schemes for dissipative particle dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2006 Mar 7;124:94104. doi: 10.1063/1.2167645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grubmüller H, Tavan P. Multiple time step algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations of proteins: How good are they? J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1534–1552. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fedosov DA, Karniadakis GE. Triple-decker: Interfacing atomistic-mesoscopic-continuum flow regimes. Journal of Computational Physics. 2009;228:1157–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, King MR. Multiscale modeling of platelet adhesion and thrombus growth. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2012 Nov;40:2345–54. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P, Sheriff J, Soares JS, Gao C, Pothapragada S, Zhang N, Deng Y, Bluestein D. Multiscale Modeling of Flow Induced Thrombogenicity Using Dissipative Particle Dynamics and Coarse Grained Molecular Dynamics. ASME 2013 Summer Bioengineering Conference; 2013; pp. V01BT36A002–V01BT36A002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ku DN. Blood flow in arteries. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 1997;29:399–434. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lei H, Fedosov DA, Karniadakis GE. Time-dependent and outflow boundary conditions for Dissipative Particle Dynamics. Journal of Computational Physics. 2011 May 31;230:3765–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Espanol P, Warren P. Statistical mechanics of dissipative particle dynamics. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 1995;30:191. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soares JS, Gao C, Alemu Y, Slepian M, Bluestein D. Simulation of platelets suspension flowing through a stenosis model using a dissipative particle dynamics approach. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013 Nov;41:2318–33. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0829-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willemsen SM, Hoefsloot HCJ, Iedema PD. No-slip boundary condition in dissipative particle dynamics. International Journal of Modern Physics C. 2000 Jul;11:881–890. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haga JH, Beaudoin AJ, White JG, Strony J. Quantification of the passive mechanical properties of the resting platelet. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 1998;26:268–277. doi: 10.1114/1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweet CR, Chatterjee S, Xu Z, Bisordi K, Rosen ED, Alber M. Modelling platelet–blood flow interaction using the subcellular element Langevin method. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2011;8:1760–1771. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mody NA, King MR. Three-dimensional simulations of a platelet-shaped spheroid near a wall in shear flow. Physics of Fluids. 2005;17:113302. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mody NA, Lomakin O, Doggett TA, Diacovo TG, King MR. Mechanics of transient platelet adhesion to von Willebrand factor under flow. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88:1432–1443. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pozrikidis C. Flipping of an adherent blood platelet over a substrate. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 2006;568:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mody NA, King MR. Platelet adhesive dynamics. Part I: characterization of platelet hydrodynamic collisions and wall effects. Biophysical Journal. 2008 Sep;95:2539–55. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.127670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mody NA, King MR. Platelet adhesive dynamics. Part II: high shear-induced transient aggregation via GPIbalpha-vWF-GPIbalpha bridging. Biophysical Journal. 2008 Sep;95:2556–74. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.128520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson AP, Plimpton SJ, Mattson W. General formulation of pressure and stress tensor for arbitrary many-body interaction potentials under periodic boundary conditions. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2009 Oct 21;131 doi: 10.1063/1.3245303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dzwinel W, Yuen DA, Boryczko K. Mesoscopic dynamics of colloids simulated with dissipative particle dynamics and fluid particle model. Journal of Molecular Modeling. 2002 Jan;8:33–43. doi: 10.1007/s00894-001-0068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han G, Deng Y, Glimm J, Martyna G. Error and timing analysis of multiple time-step integration methods for molecular dynamics. Computer Physics Communications. 2007;176:271–291. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verlet L. Computer Experiments on Classical Fluids. I. Thermodynamical Properties of Lennard-Jones Molecules. Physical Review. 1967;159:98. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plimpton S, Pollock R, Stevens M. Particle-Mesh Ewald and rRESPA for Parallel Molecular Dynamics Simulations. PPSC. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leimkuhler B, Margul DT, Tuckerman ME. Stochastic, resonance-free multiple time-step algorithm for molecular dynamics with very large time steps. Molecular Physics. 2013 Dec 1;111:3579–3594. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schlick T, Mandziuk M, Skeel RD, Srinivas K. Nonlinear resonance artifacts in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Physics. 1998 Feb 10;140:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuckerman ME, Berne BJ, Rossi A. Molecular-Dynamics Algorithm for Multiple Time Scales - Systems with Disparate Masses. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1991 Jan 15;94:1465–1469. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leimkuhler B, Shang X. On the numerical treatment of dissipative particle dynamics and related systems. 2014 arXiv preprint arXiv: 1405.4839. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heinz H, Paul W, Binder K. Calculation of local pressure tensors in systems with many-body interactions. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005 Dec;72:066704. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.066704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Apel J, Paul R, Klaus S, Siess T, Reul H. Assessment of hemolysis related quantities in a microaxial blood pump by computational fluid dynamics. Artif Organs. 2001 May;25:341–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2001.025005341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeffery GB. The motion of ellipsoidal particles in a viscous fluid. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series a-Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 1922 Nov;102:161–179. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leimkuhler B, Matthews C. Rational construction of stochastic numerical methods for molecular sampling. Applied Mathematics Research eXpress. 2013;2013:34–56. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang P, Powell R, Deng Y. Interlacing Bypass Rings to Torus Networks for More Efficient Networks. Parallel and Distributed Systems, IEEE Transactions on. 2011;22:287–295. [Google Scholar]