Abstract

This study explores relationships between lifetime and 12 month DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD), depressive symptoms and involvement with family and friends within a national sample of African American and Black Caribbean adults (n=5,191). MDD was assessed using the DSM-IV World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) and depressive symptoms were assessed using the CES-D and the K6. Findings indicated that among both populations close supportive ties with family members and friends are associated with lower rates of depression and major depressive disorder. For African Americans, closeness to family members was important for both 12 month and lifetime MDD; and both family and friend closeness were important for depressive symptoms. For Caribbean Blacks, family closeness had more limited associations with outcomes and was directly associated with psychological distress only. Negative interactions with family (conflict, criticisms), however, were associated with higher MDD and depressive symptoms among both African Americans and Black Caribbeans.

Keywords: Depression, Afro-Caribbean, West Indian, Black American, Informal Social Support, Kinship

Introduction

Research on social support from family and friends indicates that social support has beneficial effects on a range of mental health outcomes such as depression (George, 2011; Lincoln, et al., 2010; Travis et al., 2004; Wethington & Kessler, 1986), anxiety (Lincoln et al., 2010; Mehta et al., 2004), and psychological distress (Brown et al., 2009). In regards to depression, social support may be important in helping individuals cope more effectively with personal difficulties and managing the emotional distress associated with these problems. For example, perceived availability of emotional support from loved ones may reduce worry about life’s problems and daily hassles (Peirce et al., 2000). Alternatively, social support may enhance emotional functioning by reframing adverse events in ways that are less threatening. Finally, social support may provide encouragement and advice that bolster a sense of positive self-worth and competence and provide more effective strategies for handling life problems (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Social Support and Negative Interaction

Social support research primarily focuses on the beneficial aspects of social relationships. However, recent work has demonstrated that negative interactions (i.e., criticisms, arguments) with social network members, including family and friends, can have deleterious impacts on one’s mental health. Negative interactions are a direct source of stress that are associated with negative affect (Newsom et al., 2003), depression (Rook, 1984), heightened physiological reactivity (King et al., 2002), heightened susceptibility to infectious disease (Cohen et al., 1997), declines in physical functioning (Seeman & Chen, 2002) and mortality (Tanne et al., 2004). Further, negative interactions may exacerbate the effects of other types of stressors on mental health (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1988; Lincoln et al., 2005).

Bertera’s study (2005) found that social support was negatively associated with anxiety and mood disorders, while negative interaction was positively associated with anxiety and mood disorders. Furthermore, the impact of social support varied by network source. Social support from family was associated with fewer anxiety disorders and number of mood disorder episodes while support from friends was unrelated to anxiety and mood disorders. In contrast, negative interaction had a much more robust effect and was associated with an increase in the number of anxiety and mood disorders irrespective of the source (i.e., spouse, relative or friend). Finally, a recent study (Warren-Findlow et al., 2011) found that both family and friend support were associated with better self-rated emotional health among middle-aged and older African Americans. Family strain (negative interactions) was associated with lower emotional health in unadjusted analyses, but was insignificant in the multivariate context. As these studies indicate, both positive and negative aspects of social interactions from a variety of sources must be accounted for in order to fully understand the impact of social relationships on mental health.

Diversity among the Black American Population

The commonly used term, Black Americans, obscures the presence of ethnically defined subgroups within the Black population in the U.S. This is particularly evident with regard to Black Caribbeans who, despite their sizable numbers and long history in the U.S., are typically not recognized as a separate ethnic group within the Black population. As a consequence, in the vast majority of research on Black Americans, Black Caribbeans are seldom distinguished from native born African Americans and, as a result, potential differences associated with ethnicity, culture and life circumstances characterizing these distinct groups remain unexplored (Logan & Deane, 2003).

Over the past several decades, there has been a significant growth in the size of Black immigrant populations from Caribbean countries. Black Caribbeans represent roughly 4.5 % of the Black population overall and 2000 Census estimates indicate that they make up fully one-quarter of the Black population in New York, Boston, and Nassau-Suffolk, NY, and over 30% of Blacks in Miami (Logan & Deane, 2003: Table 2). The Black Caribbean presence is especially pronounced in these specific geographic and metropolitan areas. This is reflected in the establishment of ethnic enclaves within these areas that constitute a range of civic, religious, business, health care and educational initiatives and organizations that serve the Black Caribbean community. This includes Black Caribbean churches, radio stations, newspapers, restaurants, bakeries, social clubs and cricket and soccer leagues (Henke, 2001: 49–51; Taylor et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2010). However, despite the growth of the Black Caribbean foreign-born population within these specific geographic and metropolitan areas, the issue of ethnic heterogeneity within the Black racial category continues to be largely ignored in research on the entire black population in the U.S. Consequently, in research on the Black population in the United States Caribbean Blacks remain relatively “invisible” and this has resulted in very little systematic and broad-based social science research on this population. This omission is especially evident with regards to research on the association between social relationships and mental health and psychiatric disorders.

Table 2.

Multivariable weighted logistic regressions predicting 12-month major depression among African American and Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003).

| Model 1 African Americans OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 Caribbean OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Negative Interaction | 1.48 (1.19, 1.83) *** | 2.02 (1.38, 2.95) *** |

| Family Closeness | 0.72 (0.59, 0.88) ** | 0.71 (0.40, 1.25) |

| Family Contact | 0.94 (0.84, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) |

| Friend Closeness | 0.96 (0.77, 1.20) | 1.32 (0.78, 2.24) |

| Friend Contact | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) | 0.93 (0.62, 1.39) |

| Age | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) * | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) |

| Gender: Women vs. Men | 1.61 (1.15, 2.24) * | 0.70 (0.29, 1.69) |

| Marital Status: Unmarried vs. Married | 1.69 (1.04, 2.74) | 2.14 (0.78, 5.88) |

| Education in Years | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 1.03 (0.80, 1.32) |

| Ratio of Household Income to Poverty | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.99 (0.84, 1.16) |

| Social Desirability | 0.25 (0.09, 0.65) ** | 0.24 (0.01, 4.67) |

| Region | ||

| African American (Ref: South) | ||

| Northeast | 1.46 (1.06, 2.02) * | |

| Midwest | 1.99 (1.39, 2.85) *** | |

| West | 1.43 (0.73, 2.82) | |

| Caribbean: Other vs. Northeast | 1.79 (0.73, 4.43) | |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

African American and Black Caribbean Family and Friendship Networks

Both historically and contemporaneously, family and friendship-based support networks have played an important role in the lives of African Americans. African American social support networks have been instrumental in assisting single mothers, helping individuals cope with the daily stress of poverty, and in providing care to elderly relatives (Taylor et al., 1990). Additionally, African American families’ provision of emotional support has documented benefits for enhancing mental health (Lincoln et al., 2007), and buffering the stresses associated with caregiving (Brummett et al., 2012).

Similar to other immigrant groups, family and friendship networks are critical for the survival and well-being of Black Caribbeans in the United States. For Black Caribbean families’ social support is maintained through kin networks that often extend across international boundaries (Basch et al., 1994). Traditional patterns of family-based support found in the Caribbean region have been modified to meet the needs of cross-national family members. These support networks extend both material and emotional assistance and distribute risks and resources across several households in multiple transnational locations (Basch et al. 1994). Although still relatively small, an emerging body of survey research on family support among Black Caribbeans indicates that family relationships can be both a risk and protective factor for well-being and mental health factors such as marital satisfaction (Taylor et al., 2012) and suicidal behavior (Lincoln et al., 2012).

The question of social support and its association with mental health is a particularly important concern for African Americans and Black Caribbeans for several reasons. First, few studies empirically examine the complexity of social relationships among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. As a consequence, we know little about whether and how different sources of social support (e.g., family, friends) are linked to mental health. Fewer still are studies that consider whether and how negative interaction is associated with the mental health of these two groups. Finally, only a few studies explore the informal social support networks of Black Caribbeans. The vast majority of available research in this area is qualitative with little work on the correlates of receiving social support and even less research that examines the connections of social support with mental health and mental illness. As a consequence, information about whether and how social relationships from family and friends are related to mental health among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks is especially lacking.

The purpose of the current study is to investigate the association between social support from family and friends and negative interactions with family on depression and depressive symptoms using cross-sectional data from a national sample of African Americans and Black Caribbeans. As is the case with other studies of this type, the use of cross-sectional data does not permit a determination of causal relationships between social relationships with family and friends and depression. Nonetheless, our study contributes to the current literature in several important ways.

First, previous studies are based on convenience samples and/or involve specific subgroups of these populations, such as older adults (Chogahara, 1999; Mahon et al., 1998), adult caregivers (Monahan & Hooker, 1995), and pregnant women (Seguin et al., 1995). In contrast, the current study uses a nationally representative sample of African Americans and Caribbean Blacks, which allows us to generalize findings to these populations. Second, in spite of recent improvements, very few studies examine the full range of network dimensions (interaction, closeness) associated with different types and sources of support and negative interaction. Third, the study investigates DSM-IV 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D and serious psychological distress as measured by the K-6. In sum, the present study examines the complexity of social relationships in terms of their type (i.e., both positive and the negative aspects), source (e.g., family, friends) and their relationships (e.g., positive, negative) with depression, depressive symptoms and psychological distress among representative samples of African Americans and Black Caribbeans.

Methods

Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The field work for the study was completed by the Institute for Social Research’s Survey Research Center, in cooperation with the Program for Research on Black Americans. The NSAL sample has a national multi-stage probability design which consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSUs). Fifty-six of these primary areas overlap substantially with existing Survey Research Center’s National Sample primary areas. The remaining eight primary areas were chosen from the South in order for the sample to represent African Americans in the proportion in which they are distributed nationally.

The NSAL includes the first major probability sample of Black Caribbeans. For the purposes of this study, Black Caribbeans are defined as persons who trace their ethnic heritage to a Caribbean country, but who now reside in the United States, are racially classified as Black, and who are English-speaking (but may also speak another language). In both the African American and Black Caribbean samples, it was necessary for respondents to self-identify their race as black. Those self-identifying as black were included in the Black Caribbean sample if they: 1) answered affirmatively when asked if they were of West Indian or Caribbean descent, b) said they were from a country included on a list of Caribbean area countries presented by the interviewers, or c) indicated that their parents or grandparents were born in a Caribbean area country.

The data collection was conducted from February 2001 to June 2003. The interviews were administered face-to-face and conducted within respondents’ homes; respondents were compensated for their time. A total of 6,082 face-to-face interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older, including 3,570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic Whites, and 1,621 Blacks of Caribbean descent. The overall response rate was 72.3%. Response rates for individual subgroups were 70.7% for African Americans, 77.7% for Black Caribbeans, and 69.7% for non-Hispanic Whites. The response rate is excellent given that African Americans (especially lower income African Americans) are more likely to reside in major urban areas which are more difficult and expensive with respect to survey fieldwork and data collection. Final response rates for the NSAL two-phase sample designs were computed using the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines (for Response Rate 3 samples) (AAPOR 2006) (see Jackson et al. 2004 for a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample). The NSAL data collection was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Dependent Variables

There are four dependent variables in this analysis: depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D, serious psychological distress as measured by the K6, 12-month major depressive disorder and lifetime major depressive disorder. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). This abbreviated CES-D has been found to have acceptable reliability and a similar factor structure compared to the original version. Item responses are coded 1 (“hardly ever) to 3 (“most of the time”). These 12 items measure the extent to which respondents: had trouble keeping their mind on tasks, enjoyed life, had crying spells, could not get going, felt depressed, hopeful, restless, happy, as good as other people, that everything was an effort, that people were unfriendly, and that people dislike them in the past 30 days. Positive valence items were reverse coded and summed resulting in a continuous measure; a high score indicates a greater number of depressive symptoms (M = 6.68, SE = 0.17) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78).

Serious psychological distress (SPD) was measured by the K6. This is a 6-item scale designed to assess non-specific psychological distress including symptoms of depression and anxiety in the past 30 days (Kessler et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 2003). Specifically, the K6 includes items designed to identify individuals with a high likelihood of having a diagnosable mental illness and associated limitations. The K6 is intended to identify persons with mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate to serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). Positive valence items were reverse coded and summed scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of psychological distress (M = 3.79, SE = 0.12) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83).

The DSM-IV World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), a fully structured diagnostic interview, was used to assess both 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD). The mental disorders sections used for the NSAL are slightly modified versions of those developed for the World Mental Health project initiated in 2000 (World Health Organization, 2004) and the instrument used in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) (Kessler & Ustun, 2004).

The DSM-IV World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI), a fully structured diagnostic interview, was used to assess the dependent variables, 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder. The mental disorders sections used for NSAL are slightly modified versions of those developed for the World Mental Health project initiated in 2000 (World Health Organization, 2004) and the instrument used in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) (Kessler & Ustun, 2004). A full description of 12-month and lifetime depression is provided by Taylor et al. (2012).

Family and Friendship Variables

There are five independent variables representing selected measures of involvement in extended family and friendship informal social support networks. Three measures assess involvement in family support networks and two measures assess involvement in friendship support networks. Degree of subjective family closeness is measured by the question: “How close do you feel towards your family members? Would you say very close, fairly close, not too close or not close at all?” This item was also asked of friends (i.e., Subjective Friendship Closeness). Frequency of contact with family members is measured by the question: “How often do you see, write or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you? Would you say nearly every day, at least once a week, a few times a month, at least once a month, a few times a year, hardly ever or never?” This question was also asked of friends (i.e., Friend Contact). Lastly, negative interaction with family members is measured by an index of three items. Respondents were asked “Other than your (spouse/partner) how often do your family members: 1) make too many demands on you? 2) criticize you and the things you do? and 3) try to take advantage of you?” The response categories for these questions were “very often,” “fairly often,” “not too often” and “never.” Higher values on this index indicate higher levels of negative interaction with family members (M = 1.85, SE = 0.02) (Cronbach’s alpha =0.

Control Variables

Several demographic characteristics were measured, including gender, age, marital status (married, unmarried), education, poverty ratio and region (South, Northeast, Midwest, West). Poverty ratio is measured using the 2001 United States Census Bureau poverty thresholds (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2007). The Census Bureau uses a set of money income thresholds that vary by household size and composition (number of adults and children under 18 in the household) to determine who is in poverty. The poverty ratio is the ratio of household income divided by their Federal poverty threshold. Also assessed was social desirability bias. Social desirability bias is assessed using 10 items from the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale designed to assess personality factors that might bias responses to sensitive questions (Marlowe & Crowne, 1961). Accordingly, social desirability is measured as the mean of 10 items endorsed as true (1) or false (0). This scale includes items such as “I never get annoyed when people cut ahead of me in line,” “I never get lost, even in unfamiliar places,” “I have always told the truth,” “I have never lost anything,” and “It doesn’t bother me if someone takes advantage of me.”

Analysis Strategy

Weighted internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) were calculated using SAS (Version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, 2005). The distribution of basic demographic characteristics, weighted linear regression analyses and logistic regression analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN (Version 9.0, RTI International, 2004). Regression analysis was used with the two continuous dependent variables and logistic regression was used with the two dichotomous dependent variables. Odds ratio estimates and 95% confidence intervals are presented for logistic regression analyses, and beta estimates and standard errors are presented for linear regression analyses, with statistical significance determined using the design-corrected F-statistic. Standard error estimates are corrected for unequal probabilities of selection, nonresponse, poststratification, and the sample’s complex design (i.e., clustering and stratification), and results from these analyses are generalizable to the African American adult and Black Caribbean adult populations.

Results

The distribution of demographic characteristics of African American and Black Caribbean participants is presented in Table 1. Bivariate comparisons indicate that Caribbeans are on average younger, have higher mean levels of education, and are more likely to live in the Northeastern U.S. compared to African Americans. African Americans in contrast are closer to the poverty threshold and less likely to be married compared to Black Caribbeans. African Americans also report greater contact with family members, but no significant differences in other family and friendship variables were found.

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics of African American and Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003).

| African American n = 3570 |

Caribbean n = 1621 |

Total N = 5191 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime MDD, n (%) | |||

| No | 3014 (88.0) | 1415 (85.7) | 4429 (87.8) |

| Yes | 420 (12.0) | 170 (14.3) | 590 (12.2) |

| 12-Month MDD, n (%) | |||

| No | 3206 (93.3) | 1493 (91.8) | 4699 (93.2) |

| Yes | 228 (6.7) | 92 (8.2) | 320 (6.8) |

| CESD, Mean (SE) | 6.70 (0.19) | 6.40 (0.33) | 6.68 (0.17) |

| K6, Mean (SE) | 3.81 (0.13) | 3.52 (0.11) | 3.79 (0.12) |

| Negative Interaction, Mean (SE) | 1.84 (0.02) | 1.92 (0.06) | 1.85 (0.02) |

| Family Closeness, Mean (SE) | 3.64 (0.02) | 3.68 (0.03) | 3.64 (0.01) |

| Family Contact, Mean (SE) ** | 6.07 (0.03) | 5.87 (0.07) | 6.06 (0.03) |

| Friend Closeness, Mean (SE) | 3.29 (0.02) | 3.31 (0.06) | 3.29 (0.02) |

| Friend Contact, Mean (SE) | 5.58 (0.03) | 5.77 (0.12) | 5.60 (0.03) |

| Age, Mean (SE) * | 42.33 (0.52) | 40.27 (0.84) | 42.18 (0.49) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Men | 1271 (44.0) | 643 (50.87) | 1914 (44.5) |

| Women | 2299 (56.0) | 978 (49.1) | 3277 (55.5) |

| Marital Status * | |||

| Married | 1222 (41.7) | 693 (50.2) | 1915 (42.3) |

| Unmarried | 2340 (58.4) | 928 (49.9) | 3268 (57.8) |

| Education in Years, Mean (SE) ** | 12.43 (0.09) | 12.89 (0.15) | 12.46 (0.08) |

| Poverty Ratio, Mean (SE) ** | 2.68 (0.10) | 3.38 (0.24) | 2.73 (0.10) |

| Social Desirability, Mean (SE) | 0.20 (0.00) | 0.19 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.00) |

| Region, n (%) *** | |||

| South | 2330 (56.2) | 456 (29.1) | 2786 (54.4) |

| Northeast | 411 (15.7) | 1135 (55.7) | 1546 (18.5) |

| Midwest | 595 (18.8) | 12 (5.1) | 607 (17.8) |

| West | 234 (9.3) | 18 (11.1) | 252 (9.4) |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Note: Column total may not sum to total sample size due to missing data.

We conducted analyses examining 12-month MDD separately among African American and Black Caribbean participants (Table 2). In both groups, greater negative interaction with family was associated with greater odds of 12-month MDD. Family closeness was associated with lower odds of 12-month MDD among African Americans only. This same pattern is seen for lifetime MDD (Table 3). We examined four sets of interactions in African American and Black Caribbean models of 12-month and lifetime MDD. Interaction terms were examined for negative interaction and each of the following variables: family closeness, family contact, friend closeness, and friend contact. No significant interactions were detected in African American models for either 12-month or lifetime MDD, or for the Caribbean model for 12-month MDD. However, two significant interactions for lifetime MDD for Caribbeans were found. Specifically, among Black Caribbean participants, significant interactions were found for negative interaction with family and family closeness and negative interaction with family and friend closeness (Table 3, Model 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable weighted logistic regressions predicting lifetime major depression among African American and Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003)

| Model 1 African Americans OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 Caribbean OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 Caribbean OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Interaction | 1.49 (1.30, 1.71)*** | 1.80 (1.33, 2.44)*** | 3.91 (0.97, 15.74) |

| Family Closeness | 0.79 (0.65, 0.95)* | 0.83 (0.49, 1.39) | 3.02 (0.84, 10.80) |

| Family Contact | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) | 1.00 (0.67, 1.49) | 1.01 (0.67, 1.54) |

| Friend Closeness | 0.99 (0.83, 1.19) | 0.88 (0.56, 1.37) | 0.39 (0.17, 0.86)* |

| Friend Contact | 0.99 (0.89, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.38) | 1.00 (0.72, 1.39) |

| Age | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) |

| Gender: Women vs. Men | 1.58 (1.22, 2.05)*** | 1.12 (0.56, 2.23) | 1.04 (0.54, 2.02) |

| Marital Status: Unmarried vs. Married | 1.42 (1.04, 1.94)* | 2.08 (1.17, 3.71)* | 2.15 (1.20, 3.83)* |

| Education in Years | 0.99 (0.92, 1.08) | 1.10 (0.88, 1.36) | 1.09 (0.89, 1.34) |

| Ratio of Household Income to Poverty | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.14) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.16) |

| Social Desirability | 0.22 (0.11, 0.41)*** | 0.26 (0.02, 3.01) | 0.24 (0.02, 3.04) |

| Region | |||

| African American (Ref: South) | |||

| Northeast | 1.72 (1.38, 2.15)*** | ||

| Midwest | 1.90 (1.42, 1.53)*** | ||

| West | 0.98 (0.56, 1.71) | ||

| Caribbean: | |||

| Other vs. Northeast | 1.83 (0.87, 3.87) | 1.91 (0.88, 4.06) | |

| Negative Interaction* | |||

| Family Closeness | 0.58 (0.36, 0.92)* | ||

| Negative Interaction* | |||

| Friend Closeness | 1.44 (1.10, 1.88)** | ||

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

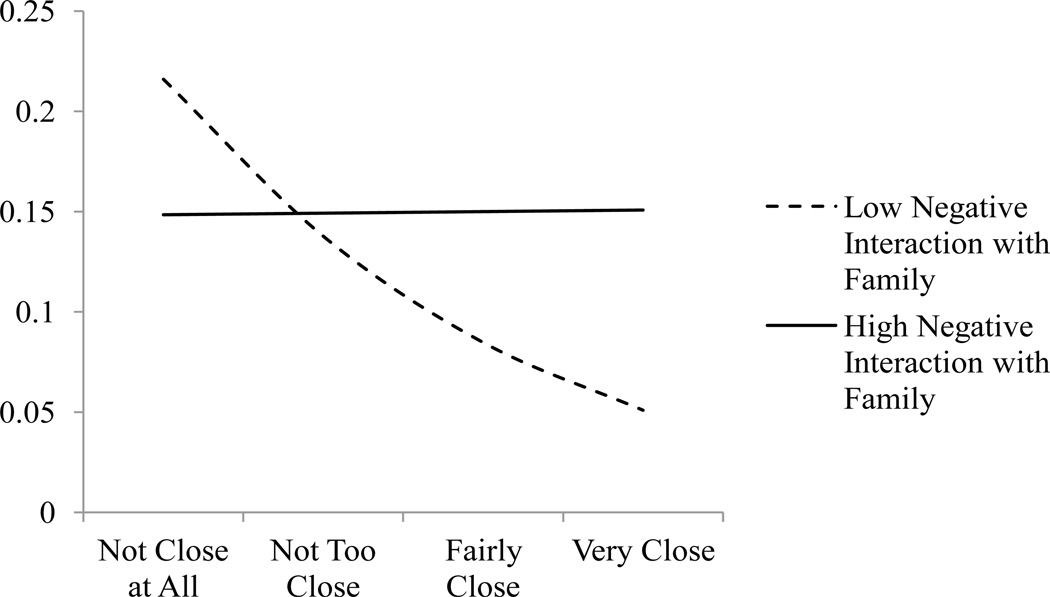

To illustrate these interactions, we constructed predicted probabilities of lifetime MDD. We chose values of one standard deviation above and below the mean value to represent low and high levels of negative interaction with family, respectively. We used values of one to four to represent the range of possible scores for both the family closeness and friend closeness variables. We chose mean values for all remaining covariates to illustrate the interaction for the average Black Caribbean participant. Among Black Caribbeans, we found that family closeness was associated with lower odds of lifetime MDD among persons with high negative interaction with family (Figure 1). For those with low levels of negative interaction with family, there was little relationship between family closeness and lifetime MDD. A different pattern of associations emerged when examining friend closeness and negative interaction with family in relation to lifetime MDD. Specifically, greater friend closeness was associated with lower probability of lifetime MDD, but only among those with low levels of negative interaction with family (Figure 2). Among those with high levels of negative interaction with family, friend closeness showed little relationship.

Figure 1.

Probability of lifetime major depression by negative interaction with family and family closeness among Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003).

Figure 2.

Probability of 12-month major depression by negative interaction with family and friend closeness among Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003).

We supplemented MDD analyses by examining psychological distress (K6) and depressive symptoms (CES-D) (Table 4). Similar to analyses for MDD, among both African Americans and Black Caribbeans, negative interaction with family was associated with higher levels of psychological distress and depressive symptoms. Family closeness was associated with lower levels of psychological distress and fewer depressive symptoms for African Americans and fewer depressive symptoms for Black Caribbeans. When examining the remaining family and friendship variables, we found differences between the two groups. Family contact was not significantly associated with either psychological distress or depressive symptoms among African Americans. However, family contact was associated with significantly lower levels of psychological distress and fewer depressive symptoms among Black Caribbeans. In contrast, friend closeness was associated with significantly lower psychological distress and fewer depressive symptoms among African Americans, but was unrelated to these outcomes among Black Caribbeans. Friend contact was associated with lower psychological distress for Caribbean Blacks and fewer depressive symptoms for African Americans. For each of the models for psychological distress and depressive symptoms, we tested interaction terms between negative interaction with family and the four family and friend variables; none of these were significant.

Table 4.

Multivariable weighted linear regressions predicting psychological distress and depressive mood among African American and Caribbean participants in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL, 2001–2003).

| African American | Caribbean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K6 b (SE) |

CESD b (SE |

K6 b (SE) |

CESD b (SE) |

|

| Intercept | 9.25 (0.88)*** | 16.48 (1.31)*** | 9.37 (2.24)*** | 17.26 (2.32)*** |

| Negative Interaction | 1.16 (0.13)*** | 1.62 (0.17)*** | 0.97 (0.18)*** | 1.64 (0.33)*** |

| Family Closeness | −0.31 (0.15)* | −0.62 (0.19)** | −0.50 (0.35) | −0.85 (0.39)* |

| Family Contact | −0.16 (0.09) | −0.18 (0.10) | −0.48 (0.23)* | −0.59 (0.26)* |

| Friend Closeness | −0.49 (0.15)** | −0.69 (0.17)*** | 0.27 (0.39) | −0.26 (0.46) |

| Friend Contact | 0.01 (0.06) | −0.18 (0.08)* | −0.27 (0.12)* | −0.20 (0.22) |

| Age | −0.03 (0.00)*** | −0.05 (0.01)*** | 0.03 (0.01)*** | −0.04 (0.01)* |

| Gender: | ||||

| Women vs. Men | 0.65 (0.19)** | 0.82 (0.20)*** | −0.32 (0.54) | −0.77 (0.92) |

| Marital Status: | ||||

| Unmarried vs. Married | −0.05 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.23) | 0.72 (0.44) | 1.22 (0.52)* |

| Education in Years | −0.24 (0.04)*** | −0.39 (0.04)*** | −0.11 (0.08) | −0.32 (0.12)** |

| Ratio of Household | ||||

| Income to Poverty | −0.16 (0.05)*** | −0.20 (0.06)** | −0.09 (0.07) | −0.17 (0.09) |

| Social Desirability | 1.42 (0.46)** | 1.58 (0.50)** | 0.45 (0.84) | 0.43 (1.14) |

| Region | ||||

| African American (Ref: South) | ||||

| Northeast | 0.34 (0.19) | 0.41 (0.37) | ||

| Midwest | 0.49 (0.26)* | 0.76 (0.33)* | ||

| West | 0.03 (0.38) | 0.15 (0.50) | ||

| Caribbean: | ||||

| Other vs. Northeast | 0.67 (0.23)** | 0.88 (0.60) | ||

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Discussion

This study investigated the association of social support from family and friends and negative interactions with family with depression and depressive symptoms among a national sample of African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Overall, the findings indicate that family and friend support is associated with less depression, whereas negative interaction with family members is linked to higher odds of depression and depressive symptoms. The findings also indicate that while the pattern for African Americans and Black Caribbeans were similar in broad respects, they diverged in terms of specific relationships. The discussion will first focus on family and friends associations with depression among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Following this, we discuss findings on the relationship between negative interaction and depression for both groups.

African American Findings

Among African Americans, subjective closeness to extended family members was significantly and negatively associated with 12-month MDD, lifetime MDD, psychological distress and depressive symptoms. Frequency of family contact was not significantly related to any of the dependent variables. Clearly, with regards to family support, the emotional bonds of subjective closeness to family members (sense of belonging and attachment) are more important for depression than mere contact with family. Subjective closeness to friends was negatively associated with the psychological distress and depressive symptoms, while friendship contact was negatively associated with the depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with other research on friendships indicating that non-kin peers play important supportive roles for African Americans (Chatters et al., 1994). Consistent with research on self-rated emotional health (Warren-Findlow et al., 2011), this study found that friend support was associated with lower odds of depression even when controlling for family sources of support. Several conclusions can be drawn from this collection of findings. First, both family and friendship networks are important for depressive symptoms. For most African Americans, family networks are more important than friendship networks in relation to 12-month and lifetime MDD. For both family and friendship networks, subjective closeness to the family/friends is a more consistent correlate of depression than frequency of contact with family/friends.

Black Caribbean Findings

The pattern of relationships between family and friend support and mental health for Black Caribbeans is somewhat different than that for African Americans. First, similar to African Americans, subjective family closeness was associated with lower odds of depressive symptoms (CES-D). Both forms of support were associated with lifetime MDD, but not in a simple or straightforward manner. As noted previously, two significant interactions emerged involving family and friend support and negative interaction. For the first interaction (depicted in Figure 1), greater subjective family closeness buffers the impact of frequent negative interactions with extended family members on lifetime depression. In other words, despite negative interactions with family members, individuals who were emotionally close to family did not experience the detrimental effects of negative interactions on lifetime MDD (at lower risk for lifetime MDD). Conversely, those who report frequent negative interactions with family and do not feel close to family members have an increased odds for lifetime MDD.

The second interaction involving subjective closeness to friends (depicted in Figure 2), indicated that closeness with friends does not buffer negative interactions with family when negative interactions occur frequently. However, subjective closeness to friends was protective for lifetime depression when negative interactions with family members were low (Figure 2). In other words, closeness to friends has protective effects on lifetime MDD, but only when negative interactions with family members are infrequent. Taken together, these findings suggest that family closeness has a more prominent role than closeness to friends as a buffer for lifetime depression.

Further, for Caribbean Blacks, family contact was associated with fewer depressive symptoms as assessed by both the K6 and the CES-D. This finding is somewhat unexpected because structural features of family networks, such as frequency of contact are generally less likely to be associated with health and mental health than subjective measures of social support (Warren-Findlow et al., 2011). In interpreting this finding, it is important to note that contemporary Caribbean Black families are often highly geographically dispersed (i.e., transnational families). For example, Caribbean Black families living in Brooklyn may also have relatives residing in Florida, Toronto, Montreal, and London, as well as their country of origin (Basch, 2001; Foner, 2005). This level of geographic dispersion reduces the likelihood of personal contact and interaction with family and, to some extent, phone and other mediums for communication (email, video chat). Findings noted previously indicated that Caribbean Blacks had less frequent interaction with their family members than African Americans. For Caribbean Blacks, it may be the case that the more limited frequency of family interaction and contact are more consequential in relation to depressive symptoms. Finally, contact with friends was associated with lower odds of psychological distress (K6) which is similar to findings for African Americans in which friend contact was associated with lower odds of depressive symptoms (CES-D).

Negative Interaction Findings for African Americans and Black Caribbeans

For both African Americans and Black Caribbeans, negative interaction with family members was the most consistent social relationship correlate and, further, was associated with all of the dependent variables examined in the expected manner. More frequent negative interactions with family members was associated with increased odds for having a major depressive disorder (12-month and lifetime) and higher levels of psychological distress and depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous research on the general population in which negative interaction is associated with greater odds of having a psychiatric disorder (Bertera, 2005; Zlotick et al., 2000) and higher levels of psychiatric distress (Lincoln et al., 2003; Lincoln et al., 2005). These findings verify that negative interaction with family members is a significant risk factor for depression and depressive symptoms among both African Americans and Black Caribbeans.

The present findings highlight both the positive and negative aspects of family relationships. Although families are important sources of joy, happiness and support, as demonstrated in previous research, families themselves can also be sources of stress. Research on family relationships and interactions underscore both the positive aspects of family life, as well as the day-to-day difficulties, conflicts and accommodations that are inherent in families. For example, interpersonal conflicts with family members (e.g., marital difficulties, conflicts with children) are frequently mentioned as being serious personal problems (Neighbors, 1997). Families are often very responsive in providing emotional and tangible assistance when members face personal difficulties (illness or job loss). However, long-standing problems (e.g., chronic unemployment, lengthy illness), may expose families to periods of prolonged stress which tax both emotional and material resources (i.e., compassion fatigue).

Consistent with other studies (Bertera, 2005; Zlotick et al., 2000) indicating that negative interactions have serious consequences for mental health status, we found that direct reports of negative interactions with family members (being taken advantage of, excessive demands, and criticism) were associated with increased risk for 12-month and lifetime major depressive disorder, psychological distress and more depressive symptoms. Unfortunately, cross-sectional data prevents a determination of causality in these relationships. However, even with longitudinal data, determining causality would be difficult because negative interactions with family members could be both a cause and consequence of depression. Families that are characterized by chronic problematic and conflictual relations reflect environments that have few and/or ineffective coping resources, difficulties in interpersonal communication, all of which engender physiological states such as heightened arousal and vigilance that are associated with prolonged stress and higher risk for depression. A 30-year prospective study found that difficult relationships with siblings prior to the age of 20 was associated with the occurrence of major depressive disorder and the use of mood altering drugs by the age of 50, indicating that negative family interactions early in the life course are associated with psychiatric disorders later in life (Waldinger et al., 2007).

Conversely, being depressed can, itself, lead to negative interactions with family members, especially given that mental illness is stigmatized and under-reported and most families do not understand the symptoms of depression. Some African Americans and Black Caribbeans may be reluctant to identify and seek treatment for depression due to cultural beliefs about emotional control and strength. Family members’ attempts to be helpful, may include comments that emphasize personal responsibility for their illness and may inadvertently, “blame the victim.” Although meant to be motivating and supportive, such comments generate additional stress for depressed individuals, make it more difficult to seek assistance from family, and may result in an exacerbation of symptoms. Importantly, this scenario illustrates how family members’ definitions and understanding of mental illness can lead to interactions and comments that are viewed as unsupportive and interpreted as negative interactions that are directed toward the individual.

Conclusions

This study has several limitations. First, because several segments of the population such as homeless and institutionalized individuals were not represented, our findings are not generalizable to these subgroups. Second, disorder-specific symptoms and behaviors may be underreported (potentially resulting in lower prevalence rates) due to non-response to sensitive questions, a common issue in survey interviewing. A third potential limitation is related to statistical power, which may be a particular concern when examining outcomes with a low prevalence and in smaller subgroups (e.g., models examining 12-month MDD among Caribbean Blacks). As in all analyses, however, statistical significance should not be the sole barometer in determining the meaningfulness of relationships, and the effect size should also be considered in gauging the relative importance of an association.

As noted earlier, causal inferences are problematic with cross-sectional data and longitudinal data are preferred. While cross-sectional data provides evidence of associations between depressive factors and family and friend social relationships, such data cannot establish a definite causal sequence. The relationship between depressive symptoms and family and friendship relations likely reflects complex and reciprocal interpersonal dynamics. Much of the research argues for a causal relationship indicating that negative interactions from others precipitate depressive episodes and symptoms. It is important to note that mental disorders can have an adverse impact on social support networks. Persons experiencing depression may view and respond to socially awkward situations and exchanges as negative or distressing. Although family and friends may refute these interpretations, further attempts may be construed as being non-supportive, critical or indications of a lack of understanding. This may lead to more interpersonal tension in families and exacerbate problems in already fragile family and friendship networks. Alternatively, social interactions with persons experiencing depression may be characterized by repeated and unsuccessful attempts to provide support. In these situations, repeated efforts to provide assistance to others (sometimes with little or no effect) may violate conventional norms of reciprocity that govern social support provision. The support provider may come to feel overtaxed by support demands and begin to view these exchanges as burdensome. In addition, support recipients are also likely conscious of the imbalances in these support exchanges and may come to think of their continued needs as evidence of their burden on family and friends who provide assistance. Research has shown that those who are the recipients of unbalanced support exchanges have higher levels of psychological distress (Liang et al., 2001; Thomas, 2010).

Despite these limitations, the significant advantages of the sample provided a unique opportunity to examine the associations between social support and negative interaction from family members and friends and depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. As one of the few studies of social relationships and depression among African Americans and Black Caribbeans, the present study suggests that close supportive ties with family members and friends are protective against depression and major depressive disorder. For African Americans, closeness to family members was clearly important for both 12-month and lifetime MDD; both family and friend closeness were important for depressive symptoms and psychological distress. For Caribbean Blacks, family closeness had more limited effects on outcomes and was directly associated with psychological distress only. Notably, for Caribbean Blacks closeness with both family and friends interacted with family negative interaction in relation to lifetime MDD. Overall, Caribbean Blacks who characterized their families as having low levels of negative interaction had lower risk of lifetime MDD than those who had families with more frequent negative interactions. However, for persons with families who engage in more frequent negative interaction, increased family closeness was associated with a reduced risk of depression. For persons with families who experience less frequent negative interactions, more family closeness was associated with increased risk of depression. The second interaction involving friend closeness indicated that for Caribbean Blacks who characterized their families as having more frequent negative interaction, levels of friend closeness had no impact on risk of lifetime MDD. However, for families with less frequent negative interaction, increased levels of friend closeness reduced the risk for lifetime MDD.

Taken together, the findings suggest that negative interactions with family may have adverse consequences for mental health (major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms) among both African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Our findings indicated that negative interaction was more likely to be significantly associated with depression and depressive symptoms than were family and friendship closeness. This is consistent with observations that negative interactions have more potent impacts on well-being than socially supportive interactions (Lincoln, 2000; Rook, 1984). Nonetheless, family closeness was associated with lower odds of major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms for African Americans and depressive symptoms for Caribbean Blacks. Further research among Caribbean Blacks, is needed to understand: 1) how quantity and quality of family contact function in relation to risk for psychological distress and depression in families that are geographically dispersed, and 2) how family and friend support operates in relation to differential risk for lifetime MDD among families that are characterized by high vs. low levels of negative interaction. Finally, additional research that clarifies the causal ordering and timing of negative interaction and social support in relation to depression, as well as the specific mechanisms involved, can help us to understand their impact on mental health among both African Americans and Caribbean Blacks.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant P30-AG15281(to Dr. Taylor) from the National Institute on Aging and by Grant R01-MH084963 (to Dr. Lincoln and Chatters) from the National Institute on Mental Health. The data collection on which this study is based was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors do not have any commercial associations which may cause a conflict of interest.

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4th edition. Lenexa, Kansas: AAPOR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Basch L. Transnational social relations and the politics of national identity: An Eastern Caribbean case study. In: Foner N, editor. Islands in the city: West Indian migration to New York. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2001. pp. 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Basch L, Schiller NG, Blanc CS. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. New York: Gordon and Breach; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bertera EM. Mental health in U.S. adults: the role of positive social support and social negativity in personal relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. 2005;22:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Mason CA, Spokane AR, Cruza-Guel MC, Lopez B, Szapocznik J. The relationship of neighborhood climate to perceived social support and mental health in older Hispanic immigrants in Miami, Florida. J Aging Health. 2009;21(3):431–459. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Williams RB, Hilliard TS, Dilworth-Anderson P. Associations of social support and 8-year follow-up depressive symptoms: Differences in African American and white caregivers. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:289–302. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.678569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jayakody R. Fictive kinship relations in Black extended families. J Comp Fam Stud. 1994;25:297–313. [Google Scholar]

- Chogahara M. A multidimensional scale for assessing positive and negative social influences on physical activity in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54:S356–S367. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.6.s356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psych Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277(24):1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foner N. In a New Land: A Comparative View of Immigration. New York: New York University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Social factors, depression and aging. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. (7th ed) 2011:149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Henke H. The West Indian Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RN, Taylor RJ, Trierweiler SJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andres G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand ST, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Meth Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Dyer CS, Shuttleworth EC. Upsetting social interactions and distress among Alzheimer’s disease family care-givers: A replication and extension. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16(6):825–837. doi: 10.1007/BF00930895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Atienza A, Castro C, Collins R. Physiological and affective responses to family caregiving in the natural setting in wives versus daughters. Int J Behav Med. 2002;9(3):176–194. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0903_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Krause NM, Bennett JM. Social exchange and well-being: is giving better than receiving? Psychol Aging. 2001;16(3):511–523. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD. Social support, negative social interactions and psychological well-being. Soc Serv Rev. 2000;74:231–252. doi: 10.1086/514478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among Black and White Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Social support, traumatic events and depressive symptoms among African Americans. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67:754–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Profiles of depressive symptoms among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Chatters LM, Himle JA, Woodward AT, Jackson JS. Emotional support, negative interaction and DSM IV lifetime disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(6):612–621. doi: 10.1002/gps.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among Black Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;53B:S225–S233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among Black Americans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1947–1958. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0512-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Deane G. Report from the Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research. Albany, NY: State University of New York; 2003. [Retrieved June 1, 2006]. Black diversity in metropolitan America. from Website: http://mumford1.dyndns.org/cen2000/BlackWhite/BlackDiversityReport/black-diversity01.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe D, Crowne DP. Social desirability and response to perceived situational demands. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1961;25:109–115. doi: 10.1037/h0041627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski A, Yarcheski TJ. Social support and positive health practices in young adults: Loneliness as a mediating variable. Clin Nurs Res. 1998;7:292–308. doi: 10.1177/105477389800700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Penninx B, Schulz R, Rubin SM, Satterfield S, Yaffe K. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety symptoms in well-functioning older adults: Findings from the Healthy Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;12:265–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan DJ, Hooker K. Health of spouse caregivers of dementia patients: The role of personality and social support. Soc Work. 1995;40:305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW. Husbands, wives, family, and friends: Sources of stress, sources of support. In: Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, Chatters LM, editors. Family Life in Black America. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 227–292. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Nishishiba M, Morgan DL, Rook KS. The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: A longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(4):746–754. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML, Mudar P. A longitudinal model of social contact, social support, depression, and alcohol use. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1):28–38. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-reported depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS. The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46(5):1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RTI International. SUDAAN: Version 9.0.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT user’s guide. Version 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T, Chen X. Risk and protective factors for physical functioning in older adults with and without chronic conditions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(3):S135–S144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin L, Potvin L, St-Denis M, Loiselle J. Chronic stressors, social support, and depression during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:583–589. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00449-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne D, Goldbourt U, Medalie JH. Perceived family difficulties and prediction of 23-year stroke mortality among middle-aged men. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(4):277–282. doi: 10.1159/000080352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Brown E, Chatters LM, Lincoln KD. Extended family support and relationship satisfaction among married, cohabiting and romantically involved African Americans and Black Caribbeans. J Afr Am Stud. 2012;16:373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Tucker MB, Lewis E. Development in research on Black families: A decade review. J Marriage Fam. 1990;52:993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Mattis JS, Joe S. Religious involvement among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Rev Relig Res. 2010;52:125–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Religious media use among African Americans, Black Caribbeans and Non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. J Afr Am Stud. 2011;15:433–454. doi: 10.1007/s12111-010-9144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA. Is it better to give or to receive? Social support and the well-being of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B:351–357. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis LA, Lyness JM, Shields CG, King DA, Cox C. Social support, depression, and functional disability in older adult primary-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Bureau of the Census. [Retrieved January 14, 2008];Poverty Thresholds for 2001 by Size of Family and Numberof Related Children Under 18 Years. 2007 from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshld/thresh01.html.

- Waldinger RJ, Vaillant GE, Orav EJ. Childhood sibling relationships as a predictor of major depression in adulthood: A 30-year prospective study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:949–954. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren-Findlow J, Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Thompson ME. Associations between social relationships and emotional well-being in middle-aged and older African Americans. Res Aging. 2011;33(6):713–734. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Kessler RC. Perceived support, received support and adjustment to stressful events. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27(1):78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Kohn R, Keitner G, Della Grotta SA. The relationship between quality of interpersonal relationships and major depressive disorder: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord. 2000;59:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]