Abstract

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters play an increasing role in the understanding of pathologic peptide deposition in neurodegenerative diseases (NDs), such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. To describe the location of the most important ABC transporters for NDs in human brain tissue, we investigated ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunohistologically in the adult human brain and pituitary. Both transporters have similar but not identical expression patterns. In brain regions with an established blood-brain barrier (BBB), ABCB1 and ABCC1 were ubiquitously expressed in endothelial cells of the microvasculature and in a subset of larger blood vessels (mostly venules). Remarkably, both transporters were also found in fenestrated capillaries in circumventricular organs where the BBB is absent. Moreover, ABCB1 and ABCC1 were also expressed in various non-endothelia cells such as pericytes, astrocytes, choroid plexus epithelia, ventricle ependymal cells, and neurons. With regard to their neuronal expression it was shown that both transporters are located in specific nerve cell populations, which are also immunopositive for three putative cell markers of purinergic cell signalling, namely 5´-nucleotidase, adenosine deaminase and nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2. Therefore, we speculate that neuronal expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 might be linked to adenosinergic/purinergic neuromodulation. Lastly, both transporters were observed in multiple adenohypophyseal cells.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1 (ABCB1), ATP-binding cassette sub-family C member 1 (ABCC1), ABC transporters, human brain, human pituitary, blood-brain barrier, circumventricular organs, neurons, purinergic signalling

1. INTRODUCTION

ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1 (ABCB1; aka P-gp - P-glycoprotein 1, MDR1 - multidrug resistance protein 1, or CD 243) and ATP-binding cassette sub-family C member 1 (ABCC1; aka MRP1 - multidrug resistance-associated protein 1) are proteins that belong to the largest superfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which play important roles as multidrug transporters in regulating drug distribution and efflux in/from the brain and other organs. ABCB1 and ABCC1 act as potent and efficient efflux pumps at the blood-brain barrier (BBB). They export drugs, xenobiotics, and metabolites from brain capillary endothelial cells, the choroid plexus cells, and the brain interstitial fluid / cerebrospinal fluid into the blood stream (reviewed in (Begley, 2004; Hartz and Bauer, 2010)), thus prominently contributing to brain detoxification, neuroprotection, neuroregeneration, and overall central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis (Pahnke et al., 2009; Schinkel and Jonker, 2003; Schumacher et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2005; Wolf et al., 2012). However, both transporters have been shown also to handle endogenous substrates that are linked to specific diseases. They are, for example, critically involved the clearance of Aβ thus being putative molecular targets for AD treatment (Cirrito et al., 2005; Gosselet et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Koldamova et al., 2010; Krohn et al., 2011; Pahnke et al., 2013; Pahnke et al., 2009; Pahnke et al., 2008; Scheffler et al., 2012; Schumacher et al., 2012; Vogelgesang et al., 2002; Vogelgesang et al., 2004). Dysfunction of ABCB1 has been associated with Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multi-systems atrophy (MSA) and very recently genetic associations with depressive disorders were found (Bartels et al., 2008; Enokido et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2014). In accordance with their function as “gatekeepers” at the BBB, ABCB1 and ABCC1 are localized in both the luminal and abluminal membranes of brain capillary endothelial cells, in adjacent pericytes and astrocytes as well as in choroid plexus epithelia and ventricular ependyma (for reviews see (Ballerini et al., 2002; Bendayan et al., 2002; Gazzin et al., 2008; Keep and Smith, 2011; Thiebaut et al., 1987; Wolf et al., 2012)). Interestingly, with the exception of the choroid plexus (Bendayan et al., 2006; Cordon-Cardo et al., 1989; Roberts et al., 2008; Soontornmalai et al., 2006), and, possibly, the area postrema (Willis et al., 2007) it is yet not clear, if the expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 is only restricted to those brain blood vessels that are part of the BBB, or if they are equally expressed in fenestrated capillaries of the circumventricular organs (CVOs, i.e. area postrema in the brainstem, the subfornical organ, the median eminence, the pineal body, the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis, choroid plexus, and neurohypophysis). Drugs that activate ABCC1 transporters functionally in the area postrema (e.g. thiethylperazine) are being used as anti-emetic and anti-vomiting treatment especially for adverse effects of chemotherapies in cancer treatment (Diaz-Rubio et al., 1991; Martin-Jimenez et al., 1987; Martin Jimenez and Diaz-Rubio, 1986; Radi, 1990).

Moreover, a neuronal occurrence of both transporters has been reported: ABCB1 was found in neurons of rat brain (Yu et al., 2011) and of foetal and neonatal human CNS (Daood et al., 2008), whereas ABCC1 expression was confined to nerve cells in the developing (Daood et al., 2008) but not adult human brain (Nies et al., 2004). However, the role of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in neurons is largely unknown. This shows that despite their enormous functional importance for normal human CNS function and brain diseases, knowledge about the brain region-specific distribution of ABCB1 and ABCC1 proteins is still fragmentary. Hence, we decided to systematically map adult human brains for the regional distribution and cellular localization of ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactivities with regard to CVOs and extravascular localizations.

2. MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1. Material and Processing

2.1.1. Post-mortem human brain tissue

All brains were obtained from the Magdeburg brain bank at the Department of Psychiatry. The case recruitment, acquisition of personal data, performance of autopsy, and handling of autoptic material were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Magdeburg University. The brains of eight human subjects (4 males, and 4 females; mean age: 53.4 ± 4.3 years) without a history of neuropsychiatric or neurological disorder were investigated. None of the subjects had a history of substance abuse or alcoholism. Clinically inert morphologic changes due to neurodegenerative or traumatic processes were ruled out by detailed neuropathological examination.

2.1.2. Human pituitary glands

Three pituitaries were obtained at autopsy (Department of Forensic Medicine, University of Essen, Germany). The donors were two female subjects (aged 55 and 59 years, who died from generalized sepsis and suicide by hanging; post-mortem intervals 24 and 14 h, respectively) and one male (aged 33 years, who was killed in a car accident; post-mortem interval 31 h). Pituitary glands were removed from the cranium, fixed in-toto in 8% formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut at 20 µm using a sliding microtome. For morphological orientation every eighth section was stained with Azan as described earlier (Bernstein et al., 2008).

2.1.3. Tissue processing

The subjects’ brains were removed within 12–26 h after death and fixed in-toto in 8% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for at least 2 months.

Frontal and occipital poles were separated by coronal sectioning anterior to the genu and posterior to the splenium of the corpus callosum. After embedding of all brain blocks in paraffin, serial coronal sections of the middle block were cut (20 µm) and mounted. The distance between the sections was 8 mm. Every 20th section was Nissl and myelin stained (Heidenhain/Woelke stain). For immunostainings frontal sections were collected at intervals of about 2.0 cm from the level 2 cm rostral to the splenium to the posterior splenium, and from the central portion of the raphe nuclei to the central portion of the olivary nuclei.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.2.1. Antisera

To immunolocalize ABCB1 and ABCC1, we used monospecific polyclonal antibodies generated in rabbits (ABCB1: Sigma HPA002199; ABCC1: Sigma HPA002380). Both antisera yielded very good and specific staining results and are known to specifically detect ABCB1 or ABCC1, resp. The specificity was recently also proven by us in Western blot analyses (Krohn et al., 2011).

2.2.2. Immunohistochemical protocols for ABCB1, ABCC1, 5´-N, ADA, NTPDase2, glutamine synthetase and GFAP

Formalin-fixed tissue sections were deparaffinized and antigen demasking was performed by boiling of the sections for 4 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Preincubation with 1.5% hydrogenperoxide for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity was followed by blocking of non-specific binding sites with 10% normal goat serum for 60 min and repeated washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The primary antibodies were diluted in PBS and applied for 48 h at 4°C in a humidity chamber. Dilutions for both anti-ABCB1 and anti-ABCC1 were 1:200. Thereafter, sections were processed with the labeled streptavidin biotin method (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and the reaction product visualized with 3,3´-diaminobenzidine. The color reaction of the immunostainings was enhanced by adding 2 ml of a 0.5% (v/v) nickel ammonium sulfate solution to the diaminobenzidine as previously described (Bernstein et al., 1999). This procedure yielded a dark purplish-blue to dark-blue color reaction product. Specificity controls included the omission of the primary antibody; its substitution with an irrelevant IgG antibody, or normal rabbit serum.

Adenosine deaminase (E.C. 3.5.4.4) and 5´-nucleotidase (E.C. 3.1.3.5) immunohistochemistry adjacent sections to those showing neuronal localization of ABCB1 and/or ABCC1 (see Results) were immunostained for either adenosine deaminase (ADA) or 5´-nucleotidase (5´-N) using a monoclonal antibody against ADA (abcam 54969, Abcam, dilution 1:50) or a polyclonal antiserum produced in goat against 5´-N (sc-248113, epitope mapping near the C-terminus of NT5DC4 of human origin; Santa Cruz; dilution 1:200). ADA immunostaining protocol further involved the application of anti-mouse peroxidase (from Biozol, Eching, Germany; dilution 1:50) and use of nickel-enhanced visualization with 3,3´diaminobenzidine as a substrate. Further incubation steps for anti-5´-N were the application of the avidin-biotin method (Vectastain-peroxidase kit) with nickel-enhanced 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen to visualise the reaction product. In order to better characterize loci of extravascular ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunostainings we also immunocolocalized with the following additional cellular markers: (1) NTPDase2 (E.C. number 3.6.1.-) using a polyclonal antiserum generated in rabbits against the human enzyme protein (antibody 102651 from abcam). The primary dilution was 1:100 in PBS. Sections were processed with the labeled streptavidin biotin method (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and the reaction product visualized with 3,3´-diaminobenzidine. The color reaction of the immunostainings was enhanced by adding nickel ammonium sulfate solution. (2) Glutamine synthetase (E.C. 6.3.1.2), employing a polyclonal antiserum produced in rabbits against human glutamine synthetase (Sigma) as recently described in detail (Bernstein et al., 2013) and (3) GFAP by use of a mouse monoclonal antibody (Roche), diluted 1.200 in PBS (Bernstein et al., 2004).

2.2.3. Morphological analysis

The Olympus BH-2 microscope was used for the qualitative analysis of the brain sections. The brain slices were investigated systematically in terms of a direct comparison between ABCB1 and ABCC1 distribution. The following brain areas were studied: cerebral cortex (parahippocampal, entorhinal, orbitofrontal, inferior temporal, medial temporal, insular [longus and breves], medial frontal, superior frontal, anterior and posterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), hippocampus (CA1–CA4 subfields, dentate gyrus, subiculum), hypothalamic nuclei, basal ganglia, septum, thalamic nuclei, cerebellum, midbrain, brain stem, and white matter. In addition, anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary were analyzed. We distinguished between the occurrence of immunoreactivities in capillaries (diameter 7 µm or less) and larger blood vessels (arterioles or venules). Special attention was paid to brain regions where the BBB is greatly reduced or even absent due to fenestrated capillaries (i.e. circumventricular organs; CVOs). To learn more about the density of ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactive blood vessels in regions with BBB and CVOs we counted their number in the CVOs and calculated their numerical densities. In addition, we estimated the density of all capillaries in both CVOs and select regions with BBB using adjacent Heidenhain/Woelcke stained sections as described earlier in sufficient detail for rat brain (Piontkewitz et al., 2012). Given that the Nissl component of the Heidenhain/Woelcke histological staining labels all capillaries, one can determine mean ratios between the numerical densities of ABCB1 or ABCC1 immunostained capillaries (expressed as number of capillary segments/mm3) and the densities of Heidenhain/Woelcke stained capillaries in the same brain region (expressed as number of capillary segments/mm3). A ratio of 1 or above would indicate that all capillaries express either ABCB1 or ABCC1. Statistical analysis of the data was done using the parametric Student´s t-test. In addition to vascular immunostainings, extra-vascular immunopositive cells were qualitatively analysed.

3. RESULTS

3. 1. Regional and cellular distribution patterns of ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactivities in the human brain

3.1. 1. Blood vessels in brain regions with BBB

Countings of capillaries immunostained for ABCB1, ABCC1, and Heidenhain-Woelcke stain revealed that in regions with BBB endothelial cells of most (if not all) capillaries in these brain areas express both ABCB1 and ABCC1 (summarized in table 1 and shown in Figs. 1A–E). However, due to the (nearly) ubiquitous appearance of both proteins in BBB brain capillaries, this result might simply reflect the overall density of human brain capillaries (Hunter et al., 2012). Of note, the intracellular staining intensity was slightly higher for ABCB1 than for ABCC1. Immunostaining was also observed in many larger vessels (mostly venules), where the expression of both proteins was not restricted to endothelial cells, but also occurred in surrounding pericytes and astrocytes end-feet processes (Fig. 1F).

Table 1.

Number of capillary segments/mm3 as revealed by ABCB1, ABCC1 and Nissl staining in different brain areas with BBB and CVOs

| Brain region |

MDT right |

MDT left |

DG right |

DG left |

SFO | Neuhyp | Apost | PinG | ChorPl | SCO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary staining | |||||||||||

| ABCB1 | 5482 ± 433 | 5589 ± 925 | 2571 ± 233 | 2718 ± 230 | 455 ± 128 | 949 ± 288 | 242 ± 88 | 99 ± 39 | 195 ± 46 | 859 ± 312 | |

| ABCC1 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 2069 ± 777 | 688 ± 202 | 863 ± 400 | not expressed | not expressed | 189 ± 62 | 574 ± 211 | |

| Nissl | 4068 ± 1442 | 4043 ± 965 | 2257 ± 919 | 2187±1154 | 1810 ± 412 | 4307 ± 431 | 2998 ± 519 | 2355 ± 278 | 4339 ± 622 | 1906 ± 416 | |

| Mean ratios ABCB1: Nissl |

1.34 | 1.38 | 1.14 | 1.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.45 | |

| Mean ratios ABCC1: Nissl |

N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.30 |

Anatomical nomenclature: MDT, mediodorsal thalamus; DG, dentate gyrus; SFO, subfornical organ; Neuhyp, neurohypophysis; Apost, area postrema; PinG Pineal gland; ChorPl, choroid plexus; SCO, subcommissural organ

Fig. 1. Expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in BBB forming cerebral microvasculature.

Fig. A Localization of ABCB1 in hippocampal capillaries. Scale bar = 70µm.

Fig. B Localization of ABCC1 in neocortical capillaries. Scale bar = 70 µm.

Fig. C Expression of ABCB1 in thalamic capillaries. Scale bar = 100µm

Fig. D Expression of ABCC1 in thalamic capillaries. Please note that compared with ABCB1 the intraendothelial staining for ABCC1 is slightly weaker. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. E ABCB1 immunopositive white matter microvasculature. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. F. ABCC1 immunopositive venule. The punctate localization of the immunoreaction is attributable to either astrocyte endfeet or to pericytes. Scale bar = 20µm.

3.1. 2 Blood vessels in circumventricular organs (CVOs)

Contrary to what was reported in the literature (Cordon-Cardo et al., 1989; Willis et al., 2007) ABCB1 and ABCC1 were found to be expressed in CVO blood vessels. ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactive material, however, decorated only subsets of CVO capillaries (tables 1 and 2): subfornical organ (SFO): ABCB1 (Fig. 2A) about 25% of all, ABCC1 (Fig. 2B) about 38% of all; neurohypophysis: ABCB1 (Fig. 2C) about 22% of all, ABCC1 (Fig. 2D) about 20% of all; area postrema (AP): ABCB1 (Fig. 2E) about 8% of all; ABCC1 not detectable; pineal organ: ABCB1 (Fig. 2E) less than 5%; ABCC1 not detectable; choroid plexus (CP), both proteins less than 5%, Fig. 3C).

Table 2.

Semi-quantitative assessment of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in CVOs

| Circumventricular organ | ABCB1 | ABCC1 |

|---|---|---|

| Subfornical organ | capillaries + astrocytes + | capillaries + astrocytes ++ |

| Vascular organ of the lamina terminalis | not studied | not studied |

| Median eminence | capillaries+ pars tuberalis cells + | capillaries + pars tuberalis cells + |

| Neurohypophysis | capillaries+ pituicytes +++ | capillaries + pituicytes + |

| Pineal gland | capillaries + homogenous staining ++ | not detectable |

| Subcommissural organ (residual in adult brain; non-fenestrated capillaries) | capillaries ++ ependymal cells + | capillaries + ependymal cells − |

| Area postrema (in a total of 4 brain stems) | capillaries ± | capillaries − |

| choroid plexus | capillaries ± epithelial cells +++ | capillaries ± epithelial cells +++ |

Average signal intensities: − absent; ± barely detectable; + weak expression; ++ moderate expression; +++ strong expression.

Fig. 2. Expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in CVOs.

Fig. A Immunodetection of ABCB1 in the capillaries of the subfornical organ. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. B Immunodetection of ABCC1 in the capillaries of the subfornical organ. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. C Strong immunostaining for ABCB1 in the neurohypophysis. Scale bar = 300µm.

Fig. D Immunolocalization of ABCC1 in the neurohypophysis. A subset of capillaries and some pituicytes express the protein. Scale bar = 200µm.

Fig. E Immunodetection of ABCB1 in a pineal gland (fragment). Besides a homogenously distributed immunostaining a very few capillaries can be seen (arrow). Unstained palish regions represent colloid cysts typical found in human pineal glands. Scale bar = 300µm.

Fig. F ABCB1 immunoreactive capillaries in the area postrema. Only a few percent of the microvessels are immunopositive. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. 3. Extravascular localization of ABCB1 and ABCC1 I. Glia, choroid plexus, ependyma.

Fig. A ABCB1 immunoreactive white matter astrocyte. Scale bar = 12µm.

Fig. B ABCC1 immunoreactive astrocytes in the hypothalamus. Scale bar = 12µm.

Fig. C ABCB1 localization in choroid plexus epithelial cells but not capillaries. Scale bar = 100µm.

Fig. D ABCC1 expression in the ependyma of the lateral ventricle. Scale bar = 100µm.

In the subcommissural organ (which is only residual in the adult human brain and possesses non-fenestrated capillaries; (Ganong, 2000)) about 45 % of all expressed ABCB1 and about 30% of all were immunopositive for ABCC1. Remarkably all CVOs studied here were characterized by the appearance of extra-vascular localization of both proteins, which was mostly attributable to astroglial cells, with the exception of the area postrema (Fig. 2F, the results are summarized in table 2).

3. 1. 3. Extravascular localization

ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactivities were also found apart from blood vessels. Besides in CVOs, numerous immunoreactive astrocytes were found scattered throughout gray and white matter (Fig. 3A) and also located in the subventricular zone (SVZ) adjacent to the lateral ventricles. Numerous ABCC1 immunoreactive astrocytes were evident in the hypothalamus (Fig. 3B). The ependymal layer of the third and the lateral ventricles as well as choroid plexus epithelial cells showed intense staining for both proteins, whereas immunopositive blood vessels were barely detectable (Fig. 3C, D). At the wall of the third ventricle a few ABCC1 positive tanycytes could be found. Occasionally, ABCB1 (but not ABCC1) immunoreactive white matter oligodendrocytes were observed. Microglial cells were not identified as expressing either ABCB1 or ABCC1 immunoreactivity.

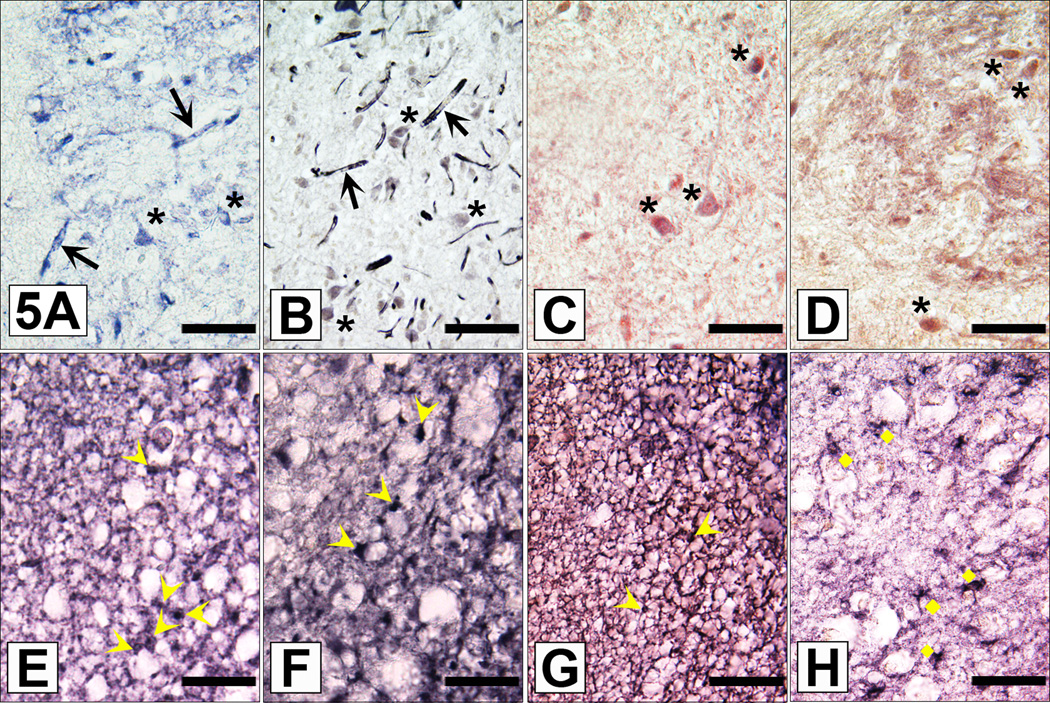

Special emphasis was given on immunostained neurons. Circumscribed groups of ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactive neurons were found in a few cortical areas (most prominent in cingulate cortex, Fig. 4A), the hippocampus (some interneurons intensely immunostained for ABCB1 but not ABCC1; Fig. 4B), the habenula (see below), the lateral geniculate, certain hypothalamic nuclei (i.e. supraoptic (SON), paraventricular (PVN) and suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN); Fig. 4C, D), Substantia nigra (Fig. 4E), the Locus coeruleus, the periaqueductal gray, the ventral tegmental area and the cerebellum (ABCB1 only, being expressed in Purkinje cells, Golgi 1 and Golgi 2 cells and some granular cells; Fig. 4F). In some neurons, ABCB1 immunoreactivity showed a punctate intracytoplasmic localization (Fig. 4A and E). This intracellular localization of ABCB1 might be of relevance in light of a recently discovered contribution of lysosomes to ABCB1 cell drug delivery (Yamagishi et al., 2013). Since subpopulations of neurons located in the above listed brain regions have repeatedly been linked with aspects of purinergic and/or adenosinergic neuromodulation (for a recent comprehensive reviews see Gampe et al. (2012) and especially Mutafova-Yambolieva and Durnin (2014), decided to look for three putative cell markers for adenosinergic/purinergic cell signalling (i.e. ADA, 5´-N and NTPDase2). We found a strong expression of ABCB1, ABCC1, 5´-N and ADA in neurons of the medial habenula (Fig. 5A–D). However, the occurrence of ADA and 5-N´ immunoreactivities was not restricted to circumscribed ABCB1 or ABCC1 immunopositive nerve cell populations, but were found to be more widely distributed throughout human brain (not shown). Therefore, we introduced a third cellular marker, the NTPDase2, which is regarded a good morphologic indicator of purinergic neurotransmission in the rat medial habenula (Gampe et al., 2012). When doing this, we were able to identify numerous NTPDase2 immunolabelled, nonstellate astroglial cells (Fig. 5E), which are regarded typical for the presence of purinergic neurotransmission (at least in the rat; Gampe et al. (2012)). Interestingly, we could confirm the observation made by Gampe et al. (2012) that NTPDase2 partly co-localizes with GFAP in the medial but not in the lateral habenula (Fig. 5G and H), and with another suitable astroglial marker, glutamine synthetase (Fig. 5F). The results are summarized in table 3.

Fig. 4. Extravascular localization of ABCB1 and ABCC1 II. Neurons.

Fig. A ABCB1 immunostaining of large neurons in the cingulate cortex. Please note the punctate intracytoplasmic localization of ABCB1 immunoreactivity. Scale bar = 25µm.

Fig. B A hippocampal interneurons intensely immunostained for ABCB1. Scale bar = 35µm.

Fig. C Multiple ABCB1 immunoreactive magnocellular neurons in the PVN. Scale bar = 35µm.

Fig. D Large ABCC1 immunoreactive neuron in the PVN. Scale bar = 10µm.

Fig. E ABCB1 expressing neurons in the substantia nigra. Please note the intracytoplasmic granules. Scale bar = 35µm.

Fig. F ABCB1 in the cerebellum. Purkinje cells and granule cells are immunostained. Scale bar = 35µm.

Fig. 5. Comparative immunolocalization of ABCB1 and ABCC1 and different cellular markers in the human medial habenula as demonstrated on consecutive brain sections.

Fig. A Expression of ABCB1 protein in capillaries (black arrows), neurons (black asterisks) and single fibers of the medial habenula. Scale bar = 70µm.

Fig. B Expression of ABCC1 protein in capillaries (black arrows) and neurons (black asterisks) of the medial habenula. Scale bar = 55µm.

Fig. C 5´-N immunoreactive neurons (black asrerisks) in the medial habenula. Scale bar = 70µm.

Fig. D ADA expressing small sized neurons (black asterisks) und fibers in the medial habenula. Scale bar = 55µm.

Fig. E NTPDase2 immunoreactive (nonstellate) habenular astrocyte cell bodies (yellow arrowheads) “forming thin cellular sheats surrounding neuronal cell bodies” (Gampe et al. 2012). Scale bar = 40µm.

Fig. F Glutamine synthetase expressing glial cells (yellow arrowheads) and fibers surounding neuronal perikarya. Like NTPDase2, the astroglial marker glutamine synthetase is expressed in the nonstellate astrocyte cell type (yellow arrowheads). Scale bar = 40µm.

Fig. G In the medial habenula the astroglial marker GFAP is predominantly expressed in nonstellate astrocytes (yellow arrowheads) and a dense network of glial processes surrounding neuronal cell bodies. Scale bar = 55µm.

Fig. H In the lateral habenula GFAP is expressed in normal (“stellate”) astrocytes (yellow diamonds). Same section as Fig. 5G. Scale bar =55µm.

Table 3.

Comparion of the cellular localization of ABCB1, ABCC1, 5´-nucleotidase (5´-N), adenosine deaminase (ADA) and nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2 (NTPDase2)

| Brain structure |

ABCB1 | ABCC1 | 5´-N | ADA | NTPDase2 (analysed in detail only in the habenula) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cingulate cortex |

few neurons, fibers |

fibers | few neurons, fibers |

Numerous neurons, fibers |

|

| hippocampus | interneurons, neuropil surrounding pyramidal cells of CA3 region |

single fibers | neuropil surrounding pyramidal cells |

single pyramidal cells, interneurons, fibers |

|

| habenula | small-sized neurons, fibers (medial habenula), fibers (lateral habenula) |

small-sized neurons, a few fibers (medial habenula) |

small-sized neurons, fibers (medial habenula), fibers (lateral habenula) |

small-sized neurons, fibers (medial habenula), neurons and fibers (lateral habenula) |

immunoreactive (nonstellate; Gampe et al. 2012) astrocyte cell bodies “forming thin cellular sheats that surround neuronal cell bodies” |

| lateral geniculate |

numerous neurons, fibers |

single neurons, fibers |

fibers | numerous neurons, fibers |

|

| hypothalamus | son: single neurons pvn: numerous magnocellular neurons scn: single neurons |

son: single neurons pvn: numerous neurons scn: single neurons; numerous astrocytes |

son : none pvn : single neurons, fibers scn : fibers |

son : none pvn : single neurons, fibers scn : fibers |

|

| Substantia nigra |

neurons, dense fibers |

dense fibers | dense fibers | neurons, dense fibers |

|

| ventral tegmental area |

dense fibers | dense fibers | dense fibers | dense fibers | |

| periaqueductal gray |

dense fibers | fibers | fibers | fibers | |

| Locus coeruleus |

single neurons, fibers |

some fibers | some fibers | fibers | |

| cerebellum | some Purkinje cells, Golgi 1 and 2 cells, some granule cells, fibers |

some granule cells, fibers |

fibers | some Purkinje cells granule cells, fibers |

3.2. Regional and cellular distribution patterns of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in the pituitary

In the neurohypophysis (a CVO) numerous ABCB1 and ABCC1 immunoreactive capillaries and pituicytes were immunolabeled. Overall, the immunostaining for ABCB1 was much stronger than for ABCC1 (see above, Fig. 2 C and D). In the adenohypophysis many cells were revealed to express ABCB1 immunoreactive material. ABCC1 expression was also confined to numerous cells; however, their regional distribution pattern was distinct from that of ABCB1 cells (Fig. 6 A, B). Remarkably, only a very few blood vessels were immunolabeled for either ABCB1 or ABCC1.

Fig. 6. ABCB1 and ABCC1 in the pituitary gland (adenohypophysis).

Fig. A ABCB1 is expressed in multiple adeohypophyseal cells. Scale bar = 35µm.

Fig. B ABCC1 is expressed in a subpopulation of adenohypophyseal cells. Scale bar = 35µm.

3. DISCUSSION

This is, at least to our knowledge, the first detailed study on the regional distribution and cellular localization of the two transporter proteins ABCB1 and ABCC1 in adult human brain. In essence, we herein show that (1) ABCB1 and ABCC1 are (nearly) ubiquitously expressed in the BBB-forming microvasculature, (2) both proteins can be found as well in some (but not all) fenestrated capillaries of CVOs, and (3) ABCB1 and ABCC1 show remarkable extravascular distribution patterns in human brain, with neurons being a major cellular component of expression.

As expected, a vast majority of blood-brain barrier forming capillaries was strongly immunostained for ABCB1, which supports, from an anatomical viewpoint, the concept of a leading role of ABCB1 as a blood-brain barrier efflux transporter in the human brain’s blood vessels (for overview see (Warren et al., 2009) (mRNA expression study) and functionally (van Assema et al., 2012). Further, the very wide immunolocalization of ABCC1 in human cerebral capillaries as shown here is in good agreement with mRNA findings of (Warren et al., 2009) on the abundant expression of this protein in human brain blood vessels. Of note, although the transporter proteins ABCB1 and ABCC1 are obviously co-expressed in almost all BBB-associated brain capillaries, they achieve a separation of functionality by preferring different classes of substrates (ABCB1: cationic amphiphilic and lipophilic compounds; ABCC1: neutral hydrophobic compounds). However, there is some evidence that under certain circumstances brain barrier associated ABCB1 may compensate for the lack of ABCC1 (Lee et al., 2004), which might be of importance in the context of treating human brain diseases (Lee and Bendayan, 2004; Warren et al., 2009).

Surprisingly, a closer look at CVO microvasculature revealed that some capillaries apart from the BBB do obviously express ABCB1 and/or ABCC1 under normal conditions. The percentage of immunolabeled CVO capillaries varied between less than 5% (choroid plexus, pineal gland) and 38% (subfornical organ). The functional importance of ABCB1 and ABCC1 expression in CVO capillaries is yet unclear. With the known exception of the subcommissural organ (Ganong, 2000), in CVO regions the tight junctions between endothelial cells are discontinuous, thus allowing a facilitated, “BBB circumventing” entry of many molecules. Hence, the classical role of ABCB1 and ABCC1 as “brain guardians” (Schinkel, 1998) can hardly be played successfully in those capillaries. Therefore, we assume that in the CVO microvasculature ABCB1 and ABCC1 may fulfil tasks beyond the well-established drug transport. Since CVO areas participate in many different processes, including secretion of glycosylated proteins into CSF, regulation of thirst and hormonal control (reviewed in (Benarroch, 2011)), it is conceivable that ABCB1 and ABCC1 play certain roles in these activities – possibly in functional interaction with ABCB1/ABCC1 expressing, noncapillary cells in CVOs (astrocytes and others). However, this speculation has to be approved by further studies.

A particularly intriguing result of our study is the occurrence of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in certain neurons, because their regional distribution pattern closely resembles that of brain areas with adenosinergic and/or purinergic cell signalling (recently summarized by (Abbracchio et al., 2009; Burnstock, 2007; Burnstock, 2013; Burnstock et al., 2011; Gampe et al., 2012; Mutafova-Yambolieva and Durnin, 2014). To learn more about a possible connection between neuronal localization of both transporter proteins and this particular type of neuromodulation, we compared the distribution of ABCB1 and ABCC1 with those of 5-N´ ADA and NTPDase2. Since all three enzymes are important regulators of purinergic cell signalling (Burnstock, 2013; Gampe et al., 2012; Kulesskaya et al., 2013; Mutafova-Yambolieva and Durnin, 2014) by degrading ATP (5-N´ degrades 5´-AMP to adenosine, ADA degrades adenosine to inosine and NTPDase2 hydrolyses extracellular nucleoside triphosphates to nucleoside monophosphates) they have repeatedly been used as putative marker enzymes to anatomically localize adenosinergic/purinergic neuromodulation (Bernstein et al., 1978; Kulesskaya et al., 2013; Staines et al., 1988; Yamamoto et al., 1987)). However, due to their wide distribution within the brain ((Burnstock et al., 2011); this study) the immunodetection of 5´-N and/or ADA in a specific brain cell compartment does not unequivocally prove the presence of purinergic/adenosinergic neuromodulation). Hence, we introduced a third, more specific cellular marker. the astrocyte-located ectonucleotidase NTPase2; Gampe et al. (2012)). After having compared the cellular expression of both ABCB1 and ABCC1 with the three putative markers of purinergic neurontransmission, we are fairly sure that at least in the medial habenula the occurrence of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in neuronal perikarya and fibers is indeed linked with aspects of purinergic neuromodulation. The medial habenula is (at least in non-humans) one of the very few regions where synaptic currents can be evoked by ATP, and ATP is the sole neurotransmitter which can elicit receptor-mediated calcium currents (reviewed in Gampe et al. (2012)). Further, in addition to the expression of 5-N´ and ADA, NTPase2 is localized in a subtype of habenular astroglial cells (Gampe et al., 2012). Interestingly, one of the mechanisms underlying ATP efflux from astrocytes seems to involve ABC transporters (at least in cell culture, Ballerini et al. (2002)). Why, however, a neurotransmission system that operates on the release of ATP should co-express transporter proteins which use ATP as a source of energy (and thereby concur for ATP) remains to be elucidated.

With respect to neurodegenerative diseases (NDs), expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 not only at the BBB but also in neurons might also be important for the excretion of Aβ or α-synuclein from these cells. Thus, projects aiming to resolve the functional relevance of cell type specific ABC transporter expression for NDs, neuronal signalling and normal brain function will be of great interest. Lastly, when studying the neurohypophysis as a CVO, we had the chance to simultaneously look at the localization of ABCB1 and ABCC1 in adenohypophyseal cells. It is well-known that brain ABCB1 is capable of regulating the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenocortical hormonal axis (Muller et al., 2003). However, the local expression of ABCB1 in the pituitary is poorly explored. A recent report suggests that both ABCB1 and ABCC1 can be detected in TtT/GF cells, which is a pituitary tumour-derived cell line with follicate-stellate cell-like characteristics (Mitsuishi et al., 2013). Our data show that both transporters are highly expressed in the anterior pituitary, although in separate (but possibly overlapping) cell populations. Further studies have to be performed in order to clarify the functional importance of this finding.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank K. Paelchen, B. Jerzykiewicz and D. Hartmann for their skilful technical assistance. The work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) PA930/9-1 and PA930/12-1 to J.P.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions:

HGB - did analyses and wrote manuscript

GH - did analyses

HD - did analyses

JH - did analyses

KT - donated human material of the pituitary glands

MK - wrote manuscript

BB - donated human brain material

JP - planned the study, donated material, and wrote manuscript

Conflict of interest: None

References

- Abbracchio MP, et al. Purinergic signalling in the nervous system: an overview. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini P, et al. Glial cells express multiple ATP binding cassette proteins which are involved in ATP release. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1789–1792. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200210070-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels AL, et al. Decreased blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein function in the progression of Parkinson's disease, PSP and MSA. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:1001–1009. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0030-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley DJ. ABC transporters and the blood-brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1295–1312. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE. Circumventricular organs: receptive and homeostatic functions and clinical implications. Neurology. 2011;77:1198–1204. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f04a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendayan R, et al. Functional expression and localization of P-glycoprotein at the blood brain barrier. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:365–380. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendayan R, et al. In situ localization of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) in human and rat brain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1159–1167. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6870.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, et al. Regional and cellular distribution of neural visinin-like protein immunoreactivities (VILIP-1 and VILIP-3) in human brain. J Neurocytol. 1999;28:655–662. doi: 10.1023/a:1007056731551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, et al. ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) 12 is expressed in rat and human brain and localized to oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:353–360. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, et al. Regional and cellular distribution patterns of insulin-degrading enzyme in the adult human brain and pituitary. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;35:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, et al. Disruption of glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle significantly impacts on suicidal behaviour: survey of the literature and own findings on glutamine synthetase. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12:900–913. doi: 10.2174/18715273113129990091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, et al. Cytochemical investigations on the localization of 5'-nucleotidase in the rat hippocampus with special reference to synaptic regions. Histochemistry. 1978;55:261–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00495765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Introduction to purinergic signalling in the brain. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;986:1–12. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4719-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, et al. Purinergic signalling: from normal behaviour to pathological brain function. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:229–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, et al. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3285–3290. doi: 10.1172/JCI25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Multidrug-resistance gene (P-glycoprotein) is expressed by endothelial cells at blood-brain barrier sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:695–698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daood M, et al. ABC transporter (P-gp/ABCB1, MRP1/ABCC1, BCRP/ABCG2) expression in the developing human CNS. Neuropediatrics. 2008;39:211–218. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Rubio E, et al. The antiemetic efficacy of thiethylperazine and methylprednisolone versus thiethylperazine and placebo in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide). A randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. Acta Oncol. 1991;30:339–342. doi: 10.3109/02841869109092382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enokido M, et al. Implication of P-Glycoprotein in Formation of Depression-Prone Personality: Association Study between the C3435T MDR1 Gene Polymorphism and Interpersonal Sensitivity. Neuropsychobiology. 2014;69:89–94. doi: 10.1159/000358063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gampe K, et al. The medial habenula contains a specific nonstellate subtype of astrocyte expressing the ectonucleotidase NTPDase2. Glia. 2012;60:1860–1870. doi: 10.1002/glia.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong WF. Circumventricular organs: definition and role in the regulation of endocrine and autonomic function. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:422–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzin S, et al. Differential expression of the multidrug resistance-related proteins ABCb1 and ABCc1 between blood-brain interfaces. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:497–507. doi: 10.1002/cne.21808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselet F, et al. Amyloid-beta peptides, Alzheimer's disease and the blood-brain barrier. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10:1015–1033. doi: 10.2174/15672050113106660174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Bauer B. Regulation of ABC transporters at the blood-brain barrier: new targets for CNS therapy. Mol Interv. 2010;10:293–304. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.5.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JM, et al. Morphological and pathological evolution of the brain microcirculation in aging and Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keep RF, Smith DE. Choroid plexus transport: gene deletion studies. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:26. doi: 10.1186/2045-8118-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, et al. Deletion of Abca7 increases cerebral amyloid-beta accumulation in the J20 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4387–4394. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4165-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koldamova R, et al. The role of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in Alzheimer's disease and neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:824–830. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn M, et al. Cerebral amyloid-beta proteostasis is regulated by the membrane transport protein ABCC1 in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3924–3931. doi: 10.1172/JCI57867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesskaya N, et al. CD73 is a major regulator of adenosinergic signalling in mouse brain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Bendayan R. Functional expression and localization of P-glycoprotein in the central nervous system: relevance to the pathogenesis and treatment of neurological disorders. Pharm Res. 2004;21:1313–1330. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000036905.82914.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, et al. Do multidrug resistance-associated protein -1 and-2 play any role in the elimination of estradiol-17 beta-glucuronide and 2,4-dinitrophenyl-S-glutathione across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier? J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:99–107. doi: 10.1002/jps.10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, et al. Novel and functional ABCB1 gene variant in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Jimenez M, et al. Antiemetic combination for PAC (cisplatin-adriamycin-cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy-induced emesis in ovarian cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1987;8:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Jimenez M, Diaz-Rubio E. Antiemetic combination for cisplatin-induced emesis. Results from a controlled study. Bull Cancer. 1986;73:294–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuishi H, et al. Characterization of a pituitary-tumor-derived cell line, TtT/GF, that expresses Hoechst efflux ABC transporter subfamily G2 and stem cell antigen 1. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:563–572. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MB, et al. ABCB1 (MDR1)-type P-glycoproteins at the blood-brain barrier modulate the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system: implications for affective disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1991–1999. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutafova-Yambolieva VN, Durnin L. The purinergic neurotransmitter revisited: A single substance or multiple players? Pharmacol Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies AT, et al. Expression and immunolocalization of the multidrug resistance proteins, MRP1-MRP6 (ABCC1-ABCC6), in human brain. Neuroscience. 2004;129:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke J, et al. Impaired mitochondrial energy production and ABC transporter function-A crucial interconnection in dementing proteopathies of the brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke J, et al. Alzheimer's disease and blood-brain barrier function-Why have anti-beta-amyloid therapies failed to prevent dementia progression? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahnke J, et al. Clinico-pathologic function of cerebral ABC transporters - implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:396–405. doi: 10.2174/156720508785132262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piontkewitz Y, et al. Effects of risperidone treatment in adolescence on hippocampal neurogenesis, parvalbumin expression, and vascularization following prenatal immune activation in rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi A. Torecan, a review of references and clinical control examinations. Ther Hung. 1990;38:56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LM, et al. Subcellular localization of transporters along the rat blood-brain barrier and blood-cerebral-spinal fluid barrier by in vivo biotinylation. Neuroscience. 2008;155:423–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, et al. Common genetic polymorphisms in the ABCB1 gene are associated with risk of major depressive disorder in male Portuguese individuals. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2014;18:12–19. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2013.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler K, et al. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms specifically modify cerebral beta-amyloid proteostasis. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:199–208. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0980-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel AH. Pharmacological insights from P-glycoprotein knockout mice. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;36:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel AH, Jonker JW. Mammalian drug efflux transporters of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family: an overview. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:3–29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher T, et al. ABC transporters B1, C1 and G2 differentially regulate neuroregeneration in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soontornmalai A, et al. Differential, strain-specific cellular and subcellular distribution of multidrug transporters in murine choroid plexus and blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience. 2006;138:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staines WA, et al. Distribution, morphology and habenular projections of adenosine deaminase-containing neurons in the septal area of rat. Brain Res. 1988;455:72–87. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, et al. ABC proteins: key molecules for lipid homeostasis. Med Mol Morphol. 2005;38:2–12. doi: 10.1007/s00795-004-0278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebaut F, et al. Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7735–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Assema DM, et al. Blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein function in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2012;135:181–189. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelgesang S, et al. Deposition of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid is inversely correlated with P-glycoprotein expression in the brains of elderly non-demented humans. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:535–541. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelgesang S, et al. The role of P-glycoprotein in cerebral amyloid angiopathy; implications for the early pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2004;1:121–125. doi: 10.2174/1567205043332225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren MS, et al. Comparative gene expression profiles of ABC transporters in brain microvessel endothelial cells and brain in five species including human. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis CL, et al. Microvascular P-glycoprotein expression at the blood-brain barrier following focal astrocyte loss and at the fenestrated vasculature of the area postrema. Brain Res. 2007;1173:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, et al. ABC Transporters and the Alzheimer's Disease Enigma. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi T, et al. P-glycoprotein mediates drug resistance via a novel mechanism involving lysosomal sequestration. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:31761–31771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, et al. Subcellular, regional and immunohistochemical localization of adenosine deaminase in various species. Brain Res Bull. 1987;19:473–484. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B activity regulates brain expression of P-glycoprotein in the kainic acid-induced seizure rats. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011:670613. doi: 10.1155/2011/670613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]