Abstract

In this work we describe the synthesis of mono- and divalent β-N- and β-S-galactopyranosides and related lactosides built on sugar scaffolds and their evaluation as substrates and inhibitors of the Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase (TcTS). This enzyme catalyzes the transfer of sialic acid from an oligosaccharidic donor in the host, to parasite βGalp terminal units and it has been demonstrated that it plays an important role in the infection. Herein, the enzyme was also tested as a tool for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of sialic acid containing glycoclusters. The transfer reaction of sialic acid was performed using a recombinant TcTS and 3’-sialyllactose as sialic acid donor, in the presence of the acceptor having βGalp non reducing ends. The products were analyzed by high performance anion exchange chromatography with pulse amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD). The ability of the different S-linked and N-linked glycosides to inhibit the sialic acid transfer reaction from 3’-sialyllactose to the natural substrate N-acetyllactosamine, was also studied. Most of the substrates behaved as good acceptors and moderate competitive inhibitors. A di-N-lactoside showed to be the strongest competitive inhibitor among the compounds tested (70% inhibition at equimolar concentration). The usefulness of the enzymatic trans-sialylation for the preparation of sialylated ligands was assessed by performing a preparative sialylation of a divalent substrate, which afforded the monosialylated compound as main product, together with the disialylated glycocluster.

Keywords: β-galactopyranosides, multivalent ligands, sialic acid, sugar scaffolds, T. cruzi trans-sialidase

Introduction

Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of American trypanosomiasis, affects millions of people in Latin America [1–2] and is transmitted to animals, including humans, by triatomine insects. The parasite is passed from the mother to the fetus during pregnancy, and also by blood transfusions and organ transplants [3]. North American and European countries are now at risk as a consequence of globalization and immigration, as Chagas’ disease is usually not tested in blood banks [4–6].

Terminal β-galactopyranosides (βGalp) present in T. cruzi mucins play an important role in the interaction between the parasite and the host since they are the acceptors for sialic acid transferred by the unique trans-sialidase (TcTS) [7–9] from host cells instead of using a sialyltransferase and the donor nucleotide CMP-sialic acid [10]. Although TcTS can be considered as “promiscuous” with respect to the sialyl donor and the β-galactopyranoside acceptor, it should be noted that the reaction is in fact specific in vivo. Only sialic acid-linked α(2→3) to β-galactopyranosides in glycoconjugates is transferred to terminal β-galactopyranoside units in the acceptor substrate, to construct the same type of linkage [11–12]. TcTS also transfers, efficiently, α(2→3)-linked N-glycolylneuraminic acid to terminal βGalp groups [13–14].

The search of efficient inhibitors for TcTS is an attractive field of research not only for their potential use for chemotherapy, since there is no equivalent enzymatic activity in the human host, but also because it could provide a tool for probing the biological functions of the enzyme. Given the 3D structure of TcTS [15–18], inhibitors may be directed to the sialic acid binding site or to the galactose acceptor site. Inhibitors of TcTS binding to the βGalp acceptor site would be highly selective, as other sialidases lack this interaction. In this direction, a group of octyl β-galactopyranosides and octyl N-acetyllactosaminides were described as substrates as well as inhibitors of the enzyme [19]. Also, the synthesis of the mucin oligosaccharides allowed the study of their acceptor and inhibitory properties [20–21]. Lactose derivatives were shown to be good inhibitors of the transfer of sialic acid to the natural acceptor, N-acetyllactosamine (LN) [22]. In particular, lactitol efficiently controlled the apoptosis triggered by TcTS [23]. The synthesis of multivalent glycoclusters designed to be high affinity ligands for specific proteins has been an active area of research during the last years [24–28]. Among them, tetravalent glycoclusters bearing β-lactosyl residues showed to have trypanocidal activity [29]. On the other hand, a recent paper described the synthesis of 1,6-linked cyclic pseudo-galacto oligosaccharides and their in vitro sialylation by recombinant TcTS [30]. Conjugation of lactose analogs with multiarm poly(ethylene glycol) increases the bioavailability in vivo [31]. Triazole-substituted β-galactopyranosides and triazole-sialyl mimetics have been synthesized by click chemistry and their inhibitory activity on the hydrolysis of 2’-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-β-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid by TcTS and trypanocidal activity were evaluated [32–33].

In the present work, we selected thioglycosidic and N-glycosidic bonds to link the acceptor sugars to a platform by click chemistry, taking into consideration that they are highly resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis [34–35]. We have previously described the synthesis of multivalent β-thiogalactopyranosides and their inhibitory activity against the β-galactosidase from E. coli [36–37]. The study of β-galactopyranosides as acceptor substrates for sialic acid is in general concomitant with the study of their inhibitory properties, as they usually behave as competitive acceptors. Thus, both aspects have been explored, even though our main goal was the use of the TcTS enzyme as a tool for the synthesis of sialylated biantennary β-N- and β-S-galactopyranosides and related lactosides. On the other hand, we considered imperative the purification and characterization of the sialylated products, an aspect that has not been often exploited in previous reports. A preparative method based on anion exchange chromatography using AG1X2 resin, followed by analytical HPAE-PAD chromatography was optimized. The inhibitory behavior of the substrates for the transfer of sialic acid to the natural acceptor N-acetyllactosamine was also evaluated.

Results and Discussion

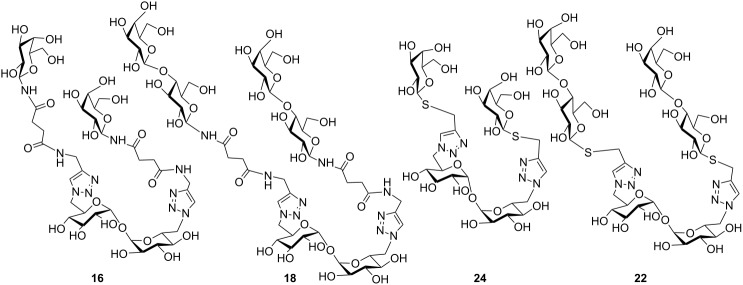

As part of our project on the synthesis and biological evaluation of multivalent ligands, two families of mono- and divalent structures were synthesized in order to study their ability as acceptors or inhibitors of the reaction catalyzed by the T. cruzi trans-sialidase. Taking into consideration that mainly ester but also glycosidic linkages are labile in biological fluids, we choose amide and thioglycosidic bonds to attach the sugar residues to the platforms.

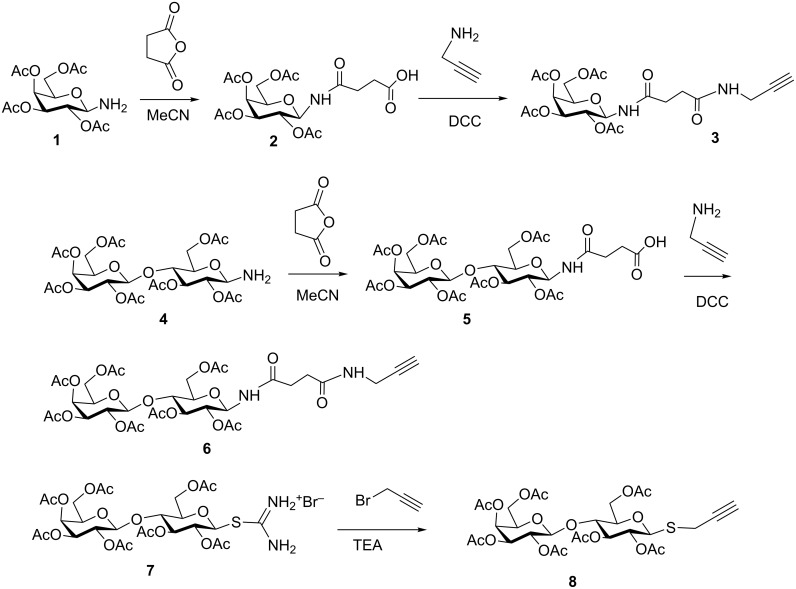

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-D-galactosylamine (1) was obtained by catalytic hydrogenation of the azide precursor and then treated with succinic anhydride to afford 2 in excellent yield, using a methodology similar to that previously described [38]. Reaction with propargylamine in the presence of DCC yielded precursor 3. A similar procedure applied to the lactosylamine derivative 4, led to compound 6 (Scheme 1). On the other hand, thiolactose derivative 8 was prepared by reaction of the thiouronium salt 7 [37] and propargyl bromide in the presence of triethylamine.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the alkynyl precursors 3, 6 and 8.

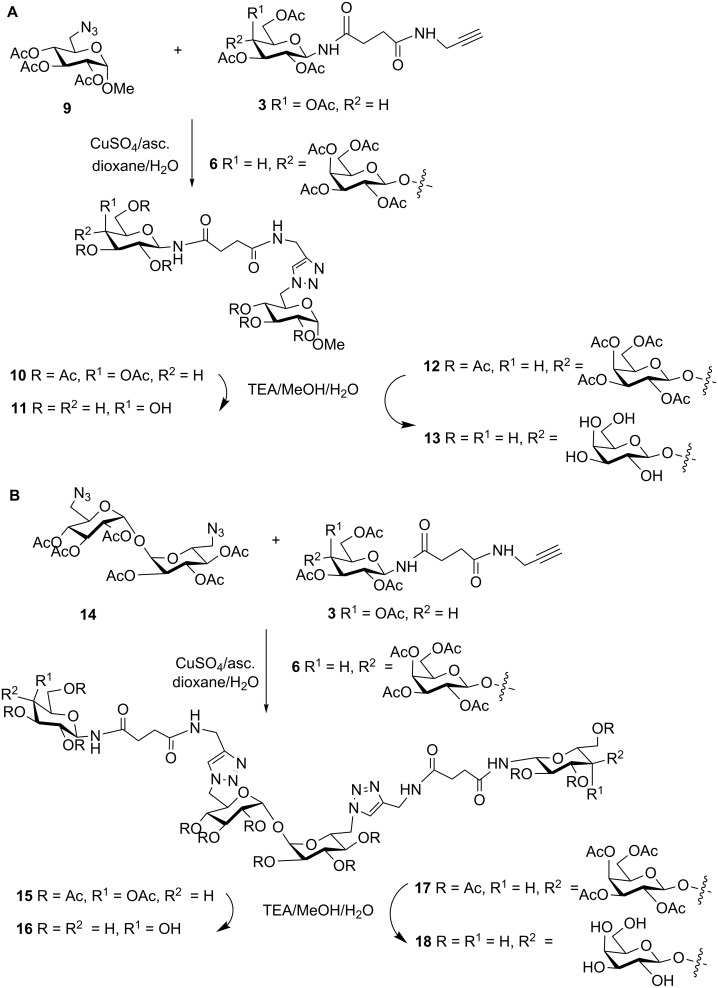

Compounds 3, 6 and 8, functionalized with terminal alkynyl residues, were convenient precursors for the synthesis of mono- and divalent ligands based on the azide scaffolds 9 and 14, readily available in our laboratory [36–37]. Thus, by cycloaddition reaction of monoazide 9 and N-galactopyranoside 3 or N-lactoside 6, two monovalent derivatives (10 and 12, respectively) were obtained after purification by column chromatography (Scheme 2A). The 1H NMR spectra showed the diagnostic signals corresponding to the aromatic protons of the triazole ring (≈7.65 ppm), as well as the anomeric signals. For compound 10, the H-1 of the βNGal appeared at 5.22 ppm (J ≈ 9.1 Hz) and the H-1 of the αGlc at 4.92 ppm (J = 3.6 Hz). In the case of 12, an additional anomeric signal corresponding to the terminal βGal residue was observed at 4.46 ppm (J = 7.9 Hz). Triazole carbon signals appeared at ca. 145.0 and 124.0 ppm in the 13C spectrum and anomeric carbons of the αGlc (96.8 ppm) scaffold, and the N-linked residue (78.5 ppm for the βNGal of 10 and 78.2 for the βNGlc moiety of 12) were clearly distinguishable. When precursors 3 and 6 reacted with α,α-trehalose diazide derivative 14, the two divalent acetylated products 15 and 17 were respectively obtained (Scheme 2B). As a consequence of the symmetry of these trehalose-based divalent products, the NMR spectra of 15 showed to be similar to those of 10, with the exception of the signal of the anomeric CH3O group in the case of 10. The same observation applied for NMR spectra of compound 17, with respect to those of 12.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the mono-(A)- and di-(B)-N-galactopyranosides and lactosides.

On the other hand, β-thiolactosides 19 and 21 were prepared (Scheme 3). Again, they showed very similar NMR spectra. For example, in the 13C spectra the anomeric signals appeared at ca. 101 ppm, 91–97 ppm and 82 ppm, corresponding respectively to the terminal βGal, αGlc from the scaffold and the βSGlc residues.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the mono- and di-S-lactosides.

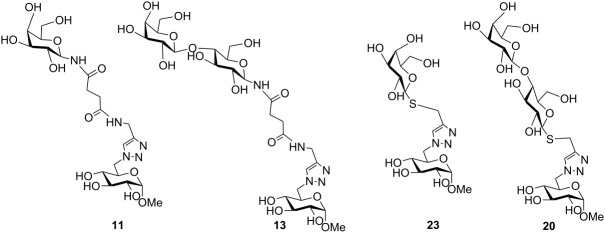

N-linked precursors 10, 12, 15 and 17 and S-glycosides 19 and 21 were treated with base in mild conditions (TEA/MeOH/H2O), to give the final deacetylated products. The solutions were desalted using a mixed bed exchange resin and purified by passing through a reversed phase mini-column. The NMR spectra of the monovalent ligands 11, 13 and 20, as well as those corresponding to the divalent 16, 18 and 22 confirmed their identity and purity.

Thiolactosides 20 and 22, together with the thiogalactosides 23 and 24 previously reported (Table 1 and Table 2) [36], constituted thio-linked analogs to the above mentioned N-linked derivatives, and thus, a set of 8 structurally related mono- and divalent acceptors was available to study the trans-sialylation reaction.

Table 1.

Evaluation of monovalent substrates in the TcTS reaction.

| |||

| Entry | Compound | Transfer (%)a | Inhibition (%) |

| 1 | 11 | 47 | 26 |

| 2 | 13 | 41 | 32 |

| 3 | 23 | 52 | 35 |

| 4 | 20 | 55 | 41 |

aCalculated by integration of the peaks of all sialylated compounds observed in the HPAEC.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the divalent substrates in the TcTS reaction.

| ||||||||||

| X | SL:X = 1:1 | SL:X = 2:1 | SL:X = 1:1 | |||||||

| % Xa | % S-Xa | % S2-Xa | % Xa | % S-Xa | % S2-Xa | Inhibition (%) | ||||

| 16 | 35 | 57 | 8 | 29 | 49 | 22 | 16 | |||

| 18 | 40 | 40 | 20 | 33 | 39 | 28 | 70 | |||

| 24 | 53 | 41 | 12 | 41 | 47 | 12 | 48 | |||

| 22 | 46 | 46 | 8 | 29 | 58 | 13 | 53 | |||

aRelated to the total amount of X (X + SX + S2X) by integration of the peaks observed in the HPAEC. X, compound tested, S-X, monosialylated compound X, S2-X, disialylated compound X, SL, sialyllactose, SL:X indicates de molar ratio of SL with respect to X.

Mono- and divalent β-N- and β-S-galactopyranosides and related lactosides as sialic acid acceptors and inhibitors in the trans-sialidase reaction

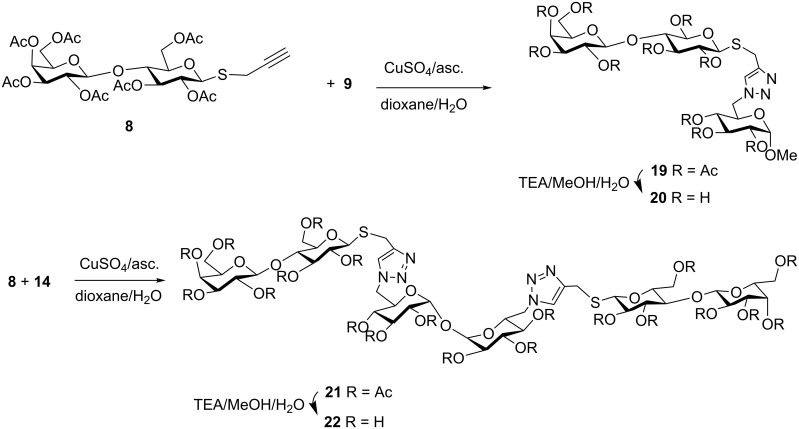

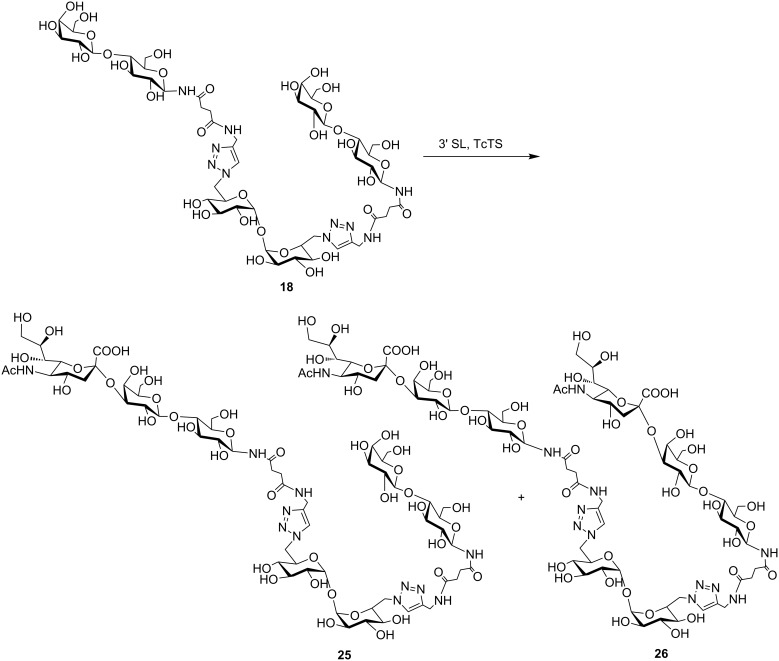

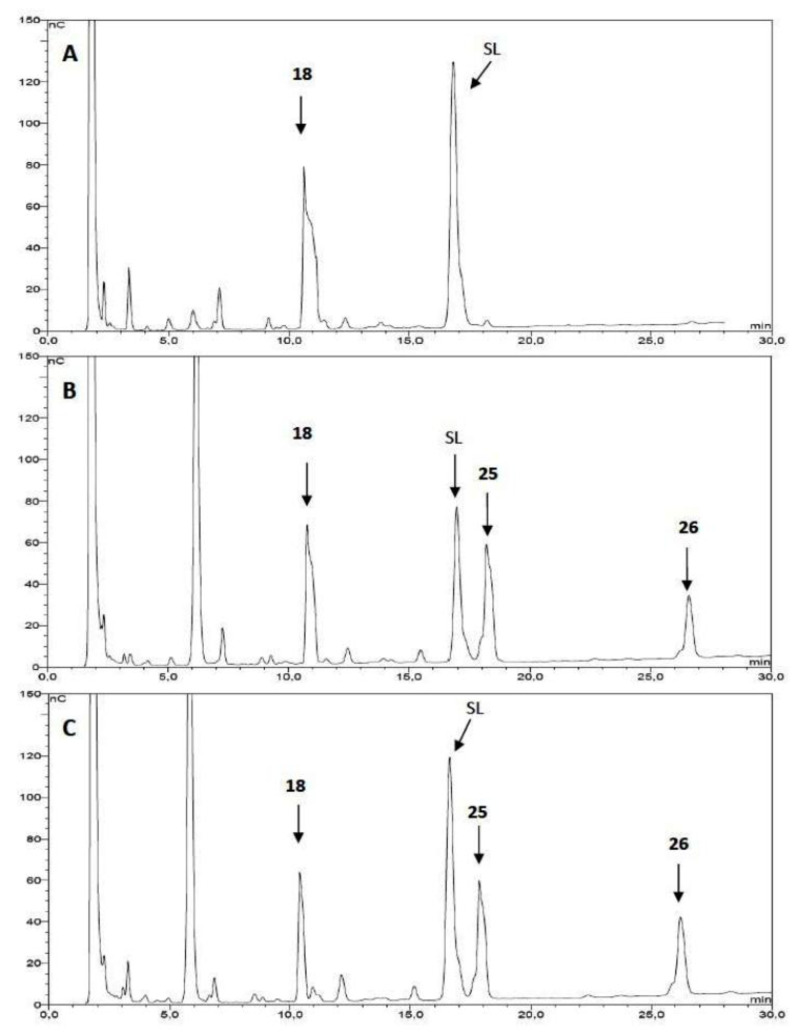

The N-galactopyranoside 11, N-lactoside 13, S-galactopyranoside 23 [36], S-lactoside 20 (Table 1) and the divalent analogous 16, 18, 24 [36] and 22 (Table 2) were first analyzed as acceptor substrates for TcTS. The reaction is depicted for substrate 18 (Scheme 4). Conditions for incubations were as previously described [22] using 1 mM of 3’-sialyllactose (SL) as donor and 1 mM of the substrate if not otherwise indicated. The reaction was analyzed by high pH anion exchange chromatography with pulse amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) as shown in Figure 1 for the sialylation of 18. In all cases, the reaction was fast and reached the equilibrium in about 15 min. All the compounds were good acceptors of sialic acid (Table 1 and Table 2). As expected, the new sialylated compounds were more retained in the anion exchange column than the original substrates. In the case of the divalent compounds 16, 18, 24 and 22 the disialylated compounds were also observed as minor products with the highest retention times. The extent of total sialylation reached about 60% for most of the divalent substrates (Table 2). To evaluate the disialylated species obtained from divalent substrates, experiments using 2 equivalents of SL were performed (Table 2 and Figure 1C). Although the disialylated compound was always the minor product an increase in the ratio between di- and monosialylated derivatives was evident. No significant changes were observed by prolonging the incubation times. It should be noted that, remarkably, in the case of compound 18, almost one third of the molecules incorporated two sialyl residues. In a pioneering work using TcTS to sialylate radiolabeled alditols obtained from parasite mucins, analysis by paper electrophoresis showed that, after incorporation of the first sialyl residue, the incorporation of sialic acid on a second galactosyl unit in the same molecule was highly reduced [39]. It was then inferred that sialylation of one residue in T. cruzi glycans modulates the susceptibility of nearby sites, and thus, polysialylated complex multiantennary glycans would not be reachable by using the enzyme. Our results suggest that the amount of disialylated glycoclusters obtained (mainly in the case of 18, and also for 16, although at a lesser extent) is related to the structure of the acceptor and the experimental conditions. When both arms of the divalent precursors are sufficiently distant one from the other, they may be independently available for the enzyme. Since determinations were performed under equilibrium conditions, we cannot rule out the possibility that the percentages obtained also depend on the stability of the sialylated products that could act as donor substrates. However, incubations performed at different times between 15 and 120 min gave very similar results (not shown). A steric effect operating on the sialylation of multiple Galp residues has been previously suggested for lactosyl lipids attached to membrane microdomains [40]. The dependence of the amount of disialylation of the divalent glycans on the concentration of 3’-sialyllactose in the incubation mixture was shown using equimolar or stoichiometric ratios of SL to acceptor (Table 2).

Scheme 4.

Sialylation of 18. SL: sialyllactose.

Figure 1.

Analysis of 18 as acceptor substrate of TcTS. A: 18 (1 mM) and 3’-sialyllactose (SL, 1 mM), without enzyme; B: 18 (1 mM) was incubated with SL (1 mM) and TcTS for 15 min at 25 °C; C: the same as B but using 2 equivalents of SL (2 mM). The incubation mixtures were analyzed by HPAEC using a CarboPac PA-10 ion exchange analytical column eluted with a linear gradient over 30 min from 20 to 200 mM NaAcO in 100 mM NaOH at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min. Structures for compounds 18, 25 and 26 are shown in Scheme 4.

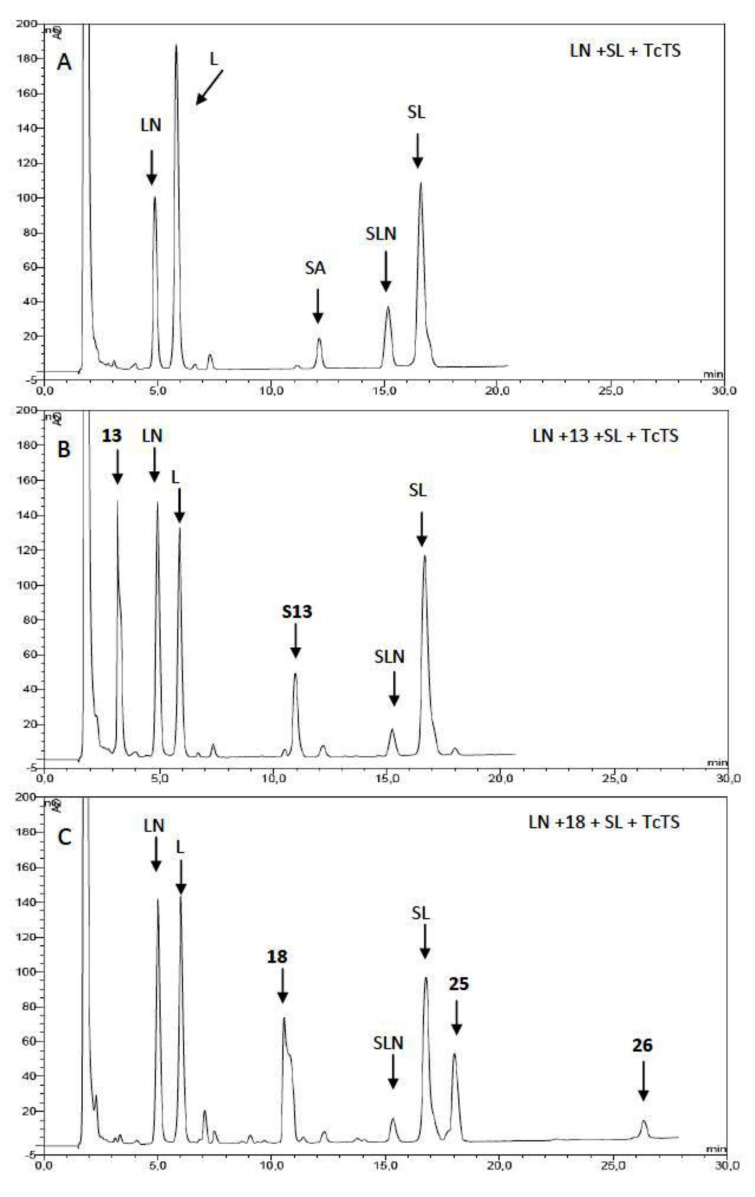

The inhibition of the sialylation of the natural substrate, N-acetyllactosamine (LN), by the synthetic derivatives was also studied (Table 1 and Table 2). Equimolar amounts of SL, the natural acceptor LN, and the potential inhibitors were incubated with TcTS and the reaction mixtures analyzed by HPAEC and compared with the sialylation of LN in absence of the inhibitor. An example is shown in Figure 2 for compounds 13 and 18. The best competitive inhibitor was compound 18 which reached 70% of inhibition of transfer to LN (Table 2). In fact, 18 is a divalent compound, and so, the concentration of lactosyl groups can be considered as twice as that of 13, which showed a 32% inhibition (Table 1). Therefore, there is no multivalent effect in the inhibition of the sialylation of LN. On the other hand, when comparing monovalent 20 (41% inhibition) and divalent 22 (53% inhibition), the latter is actually less effective per lactose residue than the monovalent 20, showing that not even a statistical effect on the inhibition is operative. This result may be a consequence of the linker structure, a fact that can be also playing a role in the proportion of sialylated species listed above (Table 1 and Table 2). On the other hand, the multivalent effect for the inhibition of certain glycosidases was recently described [41–42]. To our knowledge, there is only one previous report on the inhibition properties of multivalent ligands on the TcTS [31].

Figure 2.

Inhibition of sialylation of LN by compounds 13 and 18. A: N-acetyllactosamine (LN, 1 mM), 3’-sialyllactose (SL, 1 mM) and TcTS were incubated for 15 min at 25 °C. B: The same as A, in the presence of 13 (1 mM) as inhibitor. C: The same as A, in the presence of 18 (1 mM) as inhibitor. The incubation mixtures were analyzed by HPAEC using a CarboPac PA-10 ion exchange analytical column eluted with a linear gradient over 30 min from 20 to 200 mM NaAcO in 100 mM NaOH at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min. L: lactose; SA: sialic acid; SLN: sialyl N-acetyllactosamine; S13: monosialyl compound 13.

It should be noted that by using SL as donor substrate and quantifying the new sialylated compounds we assess that only the trans-sialidase activity is measured, and not an alternative sialidase activity. Only traces of free sialic acid have been detected (Figure 2A).

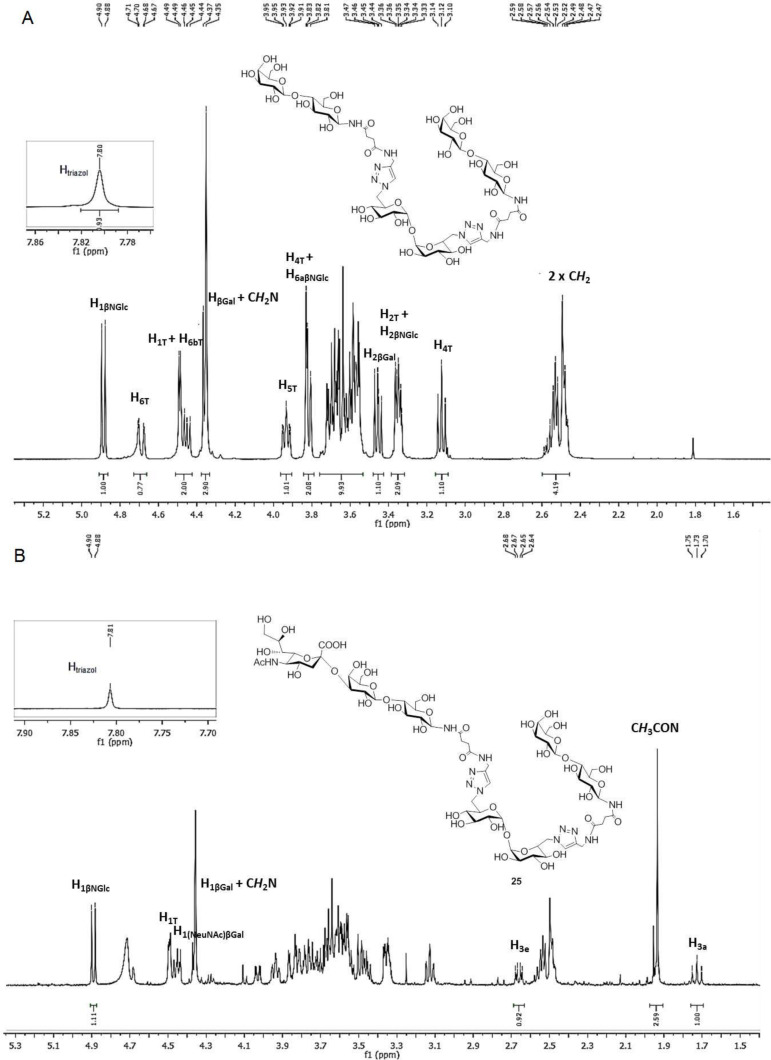

In order to prove the usefulness of the trans-sialidase reaction for the synthesis of sialylated derivatives, a preparative reaction was performed with the divalent N-lactoside 18, as it was shown to be the most sensitive, among the compounds tested, to the concentration of the SL used as donor (Scheme 4). The reaction mixture, containing unreacted 18 and sialyl derivatives 25 and 26, was purified using an AG1X2 (acetate form) resin column. After elution of neutral compounds with water, acidic derivatives were eluted with different concentrations of pyridinium acetate buffer. The eluted fractions were monitored by HPAEC. The fractions containing the monosialylated product, which appeared as a single peak at 18 min, were pooled, and 25 was characterized on the basis of the 1H NMR and two-dimensional HSQC spectra, by comparison with the spectrum of 18 (Figure 3A and Supporting Information File 1). The 1H NMR spectrum of 25 was complex, but diagnostic signals were detected (Figure 3B and Supporting Information File 1). In the anomeric region, a doublet corresponding to both anomeric protons of the two indistinguishable β-N-linked Glc residues appeared at 4.89 ppm (J = 9.3 Hz), which correlated to a 13C anomeric signal at 79.3 ppm in the HSQC spectrum. The two unresolved signals of both anomeric protons of αGlc residues of trehalose (T) were observed at 4.49 ppm (J = 3.9 Hz) and the corresponding signal at 93.4 ppm in the 13C spectrum was detected. Finally, two spots were observed at 4.44 and 4.36 ppm which correlated with signals at 102.6 and 103.1 ppm, respectively. These signals can be ascribed to both βGal residues, one of which is sialylated [(NeuNAc)βGal and terminal βGal (Supporting Information File 1)]. The appearance of signals at 2.66 ppm (H-3eq) and 1.72 ppm (H-3ax), which correlated with a signal at 34.4 ppm (C-3, NeuNAc) in the 13C spectrum, was also diagnostic of the sialic acid residue. Also, a singlet at 1.95 ppm, corresponding to the CH3CON group was observed. The structure of 25 was also confirmed by HRMS (ESI) with the presence of a peak at m/z 842.7806, corresponding to the [M + 2Na]2+ cation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the 1H NMR spectra of 18 (A) and the sialylated derivative 25 (B).

Further elution of the anion exchange column with 500 mM AcOPy gave disialylated compound 26, which appeared as a single peak at 26 min in the HPAEC. Although only 2 mg of compound 26 were obtained, analysis by ESIMS was possible, and a peak at m/z 988.3291, corresponding to the [M + 2Na]2+ cation, was observed consistent with the proposed structure.

Conclusion

Mono- and bivalent β-N and β-S-galactopyranosides and lactosides supported on sugar scaffolds were synthesized by a convergent approach using the CuAAC reaction. Monovalent as well as divalent compounds were shown to be good acceptors of sialic acid residues. Divalent substrates could also be disialylated, which means that both arms are accessible to the enzyme. By increasing the proportion of SL used as donor, a higher yield of disialylated products could be obtained and thus, this approach can be envisaged as a chemoenzymatic methodology for the synthesis of sialylated biantennary sugar derivatives. All the compounds tested were shown to be competitive inhibitors for the sialylation of the natural acceptor N-acetyllactosamine by TcTS. The best result was obtained for compound 18 which showed a 70% inhibition when equimolar amounts of substrates and inhibitor were used. The divalent N- and S-β-galactopyranosides and their sialylated products are potentially useful as inhibitors of other clinically relevant receptors of β-galactoside or sialic acid binding proteins. On the other hand, due to the ability of the compounds synthesized to inhibit the sialic acid transfer reaction from 3’-sialyllactose to the natural substrate N-acetyllactosamine, they are potential candidates for chemotherapy of Chagas’ disease, since TcTS is a fundamental enzyme in the infection process.

Experimental

The synthetic general methods are described in the Supporting Information File 2.

Synthesis of compounds 10, 12, 15, 17, 20 and 22. General procedure for the click reaction [43–44]. The corresponding azido-saccharides 9 or 14 [34] (0.20 mmol) and N-linked glycosides 3 or 6, or S-linked lactoside 8 (0.20 mmol per mol of reacting azide) were dissolved in 2.5 mL of a dioxane/H2O mixture (8:2). Copper sulfate (0.05 mmol per mol of reacting azide) and sodium ascorbate (0.10 mmol per mol of azide reacting group) were added, and the mixture was stirred at 70 °C under microwave irradiation during 50 min. The mixture was then poured into a 1:1 H2O/NH4Cl solution (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (4 × 15 mL). The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography, using the solvent system indicated in each case.

Compound 17: Compound 17 was obtained by reaction of alkyne 6 and diazide 14. Yield: 193 mg, 44%; mp 151–152 °C; [α]D20 +12.5 (c 1.0, CHCl3); Rf 0.18 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (H-triazole), 7.19 (d, J1,NH = 9.3 Hz, 1H, NH), 6.69 (t, JCH2,NH = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.41 (t, J3T,4T = J2T,3T = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-3T), 5.34 (dd, J4´,5´ = 0.7, J3´,4´ = 3.4 Hz, 1H, H-4´), 5.27 (t, J2,3 = J3,4 = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.24 (t, J1,2 = J1,NH = 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.09 (dd, J1´,2´ = 7.9, J2´,3´ = 10.4 Hz, 1H, H-2´), 4.96 (dd, J1T,2T = 3.8, J2T,3T = 9.9 Hz, 1H, H-2T), 4.94 (dd, J3´,4´ = 3.5, J2´,3´ = 10.4 Hz, 1H, H-3´), 4.92 (t, J3T,4T = J4T,5T = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-4T), 4.87 (t, J1,2 = J2,3 = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.74 (d, J1T,2T = 3.8 Hz, 1H, H-1T), 4.59 (dd, JCH2,NH = 5.0, Jgem = 15.0 Hz, 1H, CH2N), 4.54 (dd, J5T,6aT = 0.9, J6aT,6bT = 13.9 Hz, 1H, H-6aT), 4.46 (d, J1´,2´ = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H-1´), 4.40 (dd, J5,6a = 1.4, J6a,6b = 12.1 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.33 (dd, JCH2,NH = 4.5, Jgem = 15.0 Hz, 1H, CH2N), 4.26 (dd, J5T,6bT = 9.4, J6aT,6bT = 14.5 Hz, 1H, H-6bT), 4.14 (dd, J5,6a´ = 6.2, J6a´,6b´ = 11.1 Hz, 1H, H-6a´), 4.09–4.02 (m, 3H, H-5T, H-6b, H-6b´), 3.86 (ddd, J4´,5´ = 0.7, J5´,6a´ = 6.7, J5´,6b´ = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H-5´), 3.78 (t, J3,4 = 8.8, J4,5 = 9.9 Hz, 1H, H-4), 3.74 (ddd, J5,6a = 1.6, J5,6b = 4.1, J4,5 = 10.1, 1H, H-5), 2.59–2.45 (m, 4H, CH2-CH2), 2.15, 2.12, 2.06, 2.04 (3×), 2.03, 2.01 (2×), 1.96 (10 s, 30H, CH3CO); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.7, 171.8, 171.1, 170.5 (2×), 170.3 (2×), 170.2, 170.0, 169.9, 169.6, 169.1 (COCH3), 145.2 (C-4 triazole), 124.1 (C-5 triazole), 101.1 (C-1´), 91.7 (C-1T), 78.1 (C-1), 76.0 (C-4), 74.5 (C-5), 72.9 (C-3), 71.1 (C-3´), 71.0 (C-2), 70.8 (C-5´), 69.9 (C-4T) 69.5 (C-5T), 69.4 (C-3T), 69.1 (C-2´), 69.0 (C-2T), 66.7 (C-4´), 62.0 (C-6), 60.9 (C-6´), 50.8 (C-6T), 35.2 (CH2NH), 31.4, 30.8 (CH2-CH2), 21.0 (2×), 20.8 (6×), 20.7 (2×) (CH3CO-); anal. calcd for C90H120N10O53·2H2O: C, 48.56; H, 5.61; N, 6.29; found: C, 48.20; H, 5.59; N, 6.01. HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C90H121N10O53, 2189.7075; found, 2189.7081.

General procedure for O-deacetylation

Compounds 10, 12, 15, 17, 19 and 21 (0.10 mmol) were deacetylated by treatment with a solution of Et3N/MeOH/H2O 1:4:5 as previously described [45]. Further purification by a mixed bed ion-exchange resin and an octadecyl (C18) mini column was accomplished. Purity was checked by TLC (n-BuOH/EtOH/H2O, 2.5:1:1 or 1:1:1) and the corresponding Rf are indicated in each case.

Compound 18: Yield: 126 mg, 93%; [α]D20 +40.6 (c 0.6, H2O); Rf 0.34 (BuOH/EtOH/H2O 1:1:1); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.80 (s, 1H, H-triazole), 4.89 (d, J1,2 = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.71 (dd, J5T,6aT = 2.0, J6aT,6bT = 14.5 Hz, 1H, H-6aT), 4.49 (d, J1T,2T = 3.9 Hz, 1H, H-1T), 4.45 (dd, J5T,6aT = 8.0, J6aT,6bT = 14.5 Hz, 1H, H-6bT), 4.36 (d, J1´,2´ ≈ 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-1´), 4.35 (s, 2H, NH-CH2), 3.93 (ddd, J5T,6aT = 2.2, J5T,6bT = 7.9, J4T,5T = 10.2 Hz, 1H, H-5T), 3.72–3.55 (m, 9H, H-3´, H-3, H-3T, H-4, H-5´, H-5, H-6a´, H-6b´, H-6b), 3.45 (dd, J1´,2´ = 7.8, J2´,3´ = 9.8 Hz, 1H, H-2´), 3.36 (dd, J1T,2T = 3.9, J2T,3T = 9.9 Hz, 1H, H-2T), 3.34 (t, J1,2 = J2,3 = 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.12 (t, J3T,4T = J4T,5T = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-4T), 2.59–2.47 (m, 4H, CH2-CH2); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δ 175.9, 174.6 (CO), 144.7 (C-4 triazole), 124.7 (C-5 triazole), 102.9 (C-1´), 93.3 (C-1T), 79.1 (C-1), 77.8, 76.3, 75.3, 75.0, 72.6, 72.5, 71.5, 70.9, 70.8 (C-2´, C-2, C-2T, C-3´, C-3, C-3T, C-4, C-5´, C-5), 70.7 (C-4T), 70.4 (C-5T), 68.5 (C-4´), 61.0 (C-6´), 59.9 (C-6), 50.8 (C-6T), 34.4 (NH-CH2), 30.8, 30.4 (CH2-CH2); Anal. calcd for C50H80N10O33·2H2O: C, 43.35; H, 6.11; N, 10.11; found: C, 43.04; H, 5.95; N, 9.80; HRMS–ESI (m/z): [M + Na]+ calcd for C50H80N10O33Na, 1371.4781; found, 1371.4797.

Enzyme catalysis

Compounds 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, and 22–24 were incubated with TcTS in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7 buffer, 30 mM NaCl, containing 1 mM 3’-sialyllactose as donor, in a similar manner as described before [46]. Analysis of the reaction mixture was performed by HPAEC-PAD. For comparison of their capacity to act as acceptors, 1 mM of each, SL and mono- or divalent substrates were used. In the case of divalent substrates, an experiment using a 2-fold excess of SL (2 mM) was also carried out. The percentage of sialylation was calculated by integration of all the sialylated species present (in the case of monovalent compounds) or by integration of mono-, di- and non-sialylated remaining species (in the case of divalent compounds).

Inhibition of sialylation of N-acetyllactosamine

The inhibition experiments were performed as described before [22]. Briefly, monovalent compounds 11, 13, 20, and 23, or divalent 16, 18, 22, and 24, (1 mM) were incubated in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7 buffer (20 µL), 30 mM NaCl, containing 1 mM 3’-sialyllactose as donor, 1 mM N-acetyllactosamine, and recombinant TcTS (300 ng) for 15 min at room temperature. After dilution with deionized water, analysis by HPAEC-PAD was performed. Inhibition was calculated considering the amount of 3’-sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine with respect to the total amount of sialylated compounds, obtained with or without inhibitor.

Preparative sialylation of compound 18

Compound 18 (10 mg, 6.5 μmol) and SL (9.0 mg, 14 μmol) were incubated with 13 μg of recombinant TcTS in 0.2 mL of 20 mM Tris buffer pH 7.6 containing 30 mM NaCl for 14 h at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was analyzed by HPAEC. The sialylated products were purified by passing through an anion exchange resin (AG1X2, acetate form, BioRad, 1.2 × 15 cm). Neutral compounds, namely 18 and lactose, were eluted with H2O and sialylated compounds with a stepped gradient from 50 mM to 500 mM pyridinium acetate buffer pH 5.4. Fractions (1.5 mL) were collected and analyzed by HPAEC. Compound 25, the product of sialylation of 18, was eluted with 100 mM pyridinium acetate while the remaining sialyllactose was eluted with 200 mM pyridinium acetate buffer. Further elution with 500 mM buffer afforded the disialylated compound 26 (2 mg). The pooled fractions were concentrated by lyophilization. Compound 25 was further purified by passing through a SepPack C8 cartridge (Alltech) eluting with H2O to obtain 5 mg of a colourless syrup: 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O), partial assignments assisted by the HSQC spectrum: δ 7.81 (s, 2H, H-triazole), 4.89 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H, H-1-βNGlc), ≈4.69 (m, under the suppressed signal of HDO, H-6aT), 4.49 (2 d superimposed, J = 3.9 Hz, 2H, H-1T), 4.47 (m, J ≈ 8.0, 14.3 Hz, 2H, H-6bT), 4.44 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H-1-(NeuNAc)βGal), 4.37 (d, J ≈ 7.9 Hz, 1H, H-1-βGal), 4.35 (s, 4H, CH2N), 4.03 (dd, J = 3.1, 9.8 Hz, 1H, H-6NeuNAc), 3.94 (m, J = 2.3, 8.0, 10.4 Hz, 2H, H-5T), 3.87–3.45 (m, 30H), 3.37–3.33 (m, 4H, H-2T, H-2-βNGlc), 3.12 (2 t superimposed, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H, H-4T), 2.66 (dd, J = 4.6, 12.3 Hz, 1H, H-3eq-NeuNAc), 2.58–2.47 (m, 8H, 4 × CH2), 1.93 (s, 3H, CH3CON), 1.72 (t, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H, H-3ax-NeuNAc); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O), partial assignments assisted by the HSQC spectrum: δ 124.8 (CH-triazole), 103.1 (C-1-(NeuNAc)βGal*), 102.6 (C-1-βGal*), 93.4 (C-1T), 79.3 (C-1-βNGlc), 77.8, 77.7, 76.3, 75.4 (C-6-NeuNAc), 75.1, 72.6, 72.5, 71.6, 71.4 (C-2T*), 70.9, 70.8 (C-4T), 70.6 (C-2-βNGlc*), 70.4, 70.4 (C-5T), 69.3, 68.4, 68.1 (2×), 67.5, 62.6 (2×), 61.0, 59.8 (2×), 51.6, 50.8 (C-6T), 39.4 (C-3-NeuNAc), 34.4 (CH2N), 30.7, 30.4 (CH2-CH2), 22.2 (CH3CON); ESIMS (m/z): [M + 2Na]2+ calcd for C61H97N11Na2O41, 842.7814; found, 842.7806.

Disialylated compound 26 (2 mg) was obtained by using the anion exchange column and elution with 500 mM AcOPy: ESIMS (m/z): [M + 2Na]2+ calcd for C72H114N12Na2O49: 988.3291; found: 988.3291.

Supporting Information

Experimental section and data of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10–13, 15–22 and 25.

Copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10–13, 15–22 and 25.

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Campetella and his group from Universidad Nacional General San Martín (UNSAM) Argentina, for the kind gift of trans-sialidase from T. cruzi. Support for this work from the National Agency for Promotion of Science and Technology, ANPCyT, Project PICT Bicentenario 2010 – No. 1080, the National Research Council CONICET and the University of Buenos Aires is gratefully acknowledged. María E. Cano is a fellow from CONICET. Rosalia Agusti, María Laura Uhrig and Rosa M. de Lederkremer are research members of CONICET.

Contributor Information

María Laura Uhrig, Email: mluhrig@qo.fcen.uba.ar.

Rosa M de Lederkremer, Email: lederk@qo.fcen.uba.ar.

References

- 1.Brener Z. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1973;27:347–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.27.100173.002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moncayo A. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:577–591. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762003000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rassi A, Rassi A, Marin-Neto J A. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery S P, Starr M C, Cantey P T, Edwards M S, Meymandi S K. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:814–818. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gascon J, Bern C, Pinazo M-J. Acta Trop. 2010;115:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmunis G A, Yadon Z E. Acta Trop. 2010;115:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buscaglia C A, Campo V A, Frasch A C C, Di Noia J M. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:229–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giorgi M E, de Lederkremer R M. Carbohydr Res. 2011;346:1389–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meinke S, Thiem J. Top Curr Chem. 2012;128:330–349. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schenkman S, Jiang M-S, Hart G W, Nussenzweig V. Cell. 1991;65:1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90008-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandekerckhove F, Schenkman S, Pontes de Carvalho L, Tomlinson S, Kiso M, Yoshida M, Hasegawa A, Nussenzweig V. Glycobiology. 1992;2:541–548. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrero-Garcia M A, Trombetta S E, Sánchez D O, Reglero A, Frasch A C C, Parodi A J. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:765–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agusti R, Giorgi M E, de Lederkremer R M. Carbohydr Res. 2007;342:2465–2469. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroven A, Meinke S, Ziegelmüller P, Thiem J. Chem – Eur J. 2007;13:9012–9021. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buschiazzo A, Amaya M F, Cremona M L, Frasch A C C, Alzari P M. Mol Cell. 2002;10:757–768. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amaya M F, Buschiazzo A, Nguyen T, Alzari P M. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:773–784. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaya M F, Watts A G, Damager I, Wehenkel A, Nguyen T, Buschiazzo A, Paris G, Frasch A C C, Withers S G, Alzari P M. Structure. 2004;12:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meinke S, Schroven A, Thiem J. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4487–4497. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01176b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison J A, Kartha R K P, Fournier E J L, Lowary T L, Malet C, Nilsson U J, Hindsgaul O, Schenkman S, Naismith J H, Field R A. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:1653–1660. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00826e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campo V L, Carvalho I, Allman S, Davis B G, Field R A. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:2645–2657. doi: 10.1039/b707772f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Lederkremer R M, Agusti R. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2009;62:311–366. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(09)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agusti R, Paris G, Ratier L, Frasch A C C, de Lederkremer R M. Glycobiology. 2004;14:659–670. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mucci J, Risso M G, Leguizamón M S, Frasch A C C, Campetella O. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1086–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitov P I, Sadowska J M, Mulvey G, Armstrong G D, Ling H, Pannu N S, Read R J, Bundle D R. Nature. 2000;403:669–672. doi: 10.1038/35001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maierhofer C, Rohmer K, Wittmann V. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:7661–7676. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiessling L L, Geswicki J E, Strong L E. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:2348–2368. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chabre Y M, Roy R. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2010;63:165–393. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(10)63006-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingras M, Chabre Y M, Roy M, Roy R. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4823–4841. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60090d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galante E, Geraci C, Sciuto S, Campo V L, Carvalho I, Sesti-Costa R, Guedes P M M, Silva J S, Hill L, Nepogodiev S A, et al. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:5902–5912. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campo V L, Carvalho I, Da Silva C H T P, Schenkman S, Hill L, Nepogodiev S A, Field R A. Chem Sci. 2010;1:507–514. doi: 10.1039/c0sc00301h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giorgi M E, Ratier L, Agusti R, Frasch A C C, de Lederkremer R M. Glycobiology. 2012;22:1363–1373. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carvalho I, Andrade P, Campo V L, Guedes P M M, Sesti-Costa R, Silva J S, Schenkman S, Dedola S, Hill L, Rejzek M, et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:2412–2427. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campo V L, Sesti-Costa R, Carneiro Z A, Silva J S, Schenkman S, Carvalho I. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driguez H. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:311–318. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010504)2:5<311::AID-CBIC311>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Driguez H. Top Curr Chem. 1997;187:85–116. doi: 10.1007/BFb0119254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cagnoni A J, Varela O, Gouin S G, Kovensky J, Uhrig M L. J Org Chem. 2011;76:3064–3077. doi: 10.1021/jo102421e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cagnoni A J, Varela O, Uhrig M L, Kovensky J. Eur J Org Chem. 2013:972–983. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201201412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy P V, Bradley H, Tosin M, Pitt N, Fitzpatrick G M, Glass W K. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5692–5704. doi: 10.1021/jo034336d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Previato J O, Jones C, Xavier M T, Wait R, Travassos L R, Parodi A J, Mendonça-Previato L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7241–7250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noble G T, Craven F L, Segarra-Maset M D, Reyes Martinez J E, Šardzik R, Flitsch S L, Webb S J. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:9272–9278. doi: 10.1039/C4OB01852D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Compain P, Bodlenner A. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:1239–1251. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durka M, Buffet K, Iehl J, Holler M, Nierengarten J-F, Vincent S P. Chem – Eur J. 2012;18:641–651. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rostovtsev V V, Green L G, Fokin V V, Sharpless K B. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tornøe C W, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cagnoni A J, Varela O, Kovensky J, Uhrig M L. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:5500–5511. doi: 10.1039/c3ob41074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agusti R, Giorgi M E, Mendoza V M, Gallo-Rodriguez C, de Lederkremer R M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:2611–2616. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental section and data of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10–13, 15–22 and 25.

Copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10–13, 15–22 and 25.