Introduction

Cervical cancer remains the second most common cancer among women of East African descent with a high level of mortality [1-3]. In 2012, the World Health Organization reported a cervical cancer incidence rate in Somalia of 34.8 new cases per 100,000 and mortality from cervical cancer at 22.5 per 100,000; these figures contrast sharply with the relatively low incidence and mortality for women in North America; 6.6 and 2.5 per 100,000 women, respectively [4].

Due to political instability in various regions in Africa, an increasing number of refugees are resettling in other countries [5]. Somali immigrants account for the largest proportion of African refugees coming to the U.S. [6]. Given this population growth and cervical cancer incidence rates in the Somali women, there is a growing need to further explore their health seeking practices and behaviors. Advances in cervical cancer control have resulted in reduction of cervical cancer morbidity and mortality among the general U.S. population [7, 8].This progress is largely attributed to the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening programs [9, 10]. Despite this progress, not all racial, ethnic or minority groups in the U.S. have benefitted equally [11, 12].

Studies show lower cervical cancer screening rates among immigrant women compared to the general U.S. population [13-15]. One such group is the Somali immigrant women in the U.S., Two studies have shown that Somali women have lower cancer screening rates compared to other African immigrants groups [16, 17]. Carroll and colleagues found that Somali women were not familiar with the tests and concepts used for cancer screening services [18]. Other studies found that limited knowledge about cancer screening, language difficulties, fear of the test, embarrassment exposing one's body and negative past experiences have greatly contributed to the low use of cancer screening services in this immigrant population [19-22].

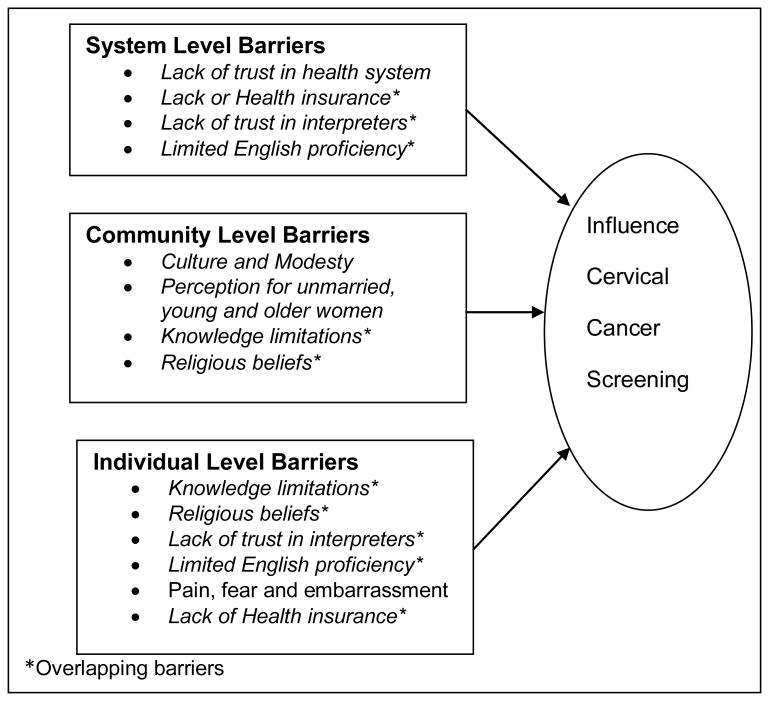

Although several studies identify barriers and facilitators to cancer screening among Somali immigrant women in the U.S., they do not explain how these barriers overlap across different ecological levels. To address this gap, we adopted the socio-ecological framework (Figure 1) [23] to cluster identified screening barriers at multiple levels. This framework has been utilized to develop multilevel intervention models to impact cancer screening behaviors [24-27]. We conducted a qualitative study with the aim of exploring suitable language, structure, and context to describe cervical cancer prevention and screening methods among women in Minnesota's Somali community.

Figure 1. Multilevel System Barriers.

Methods

This work was a result of a partnership between a Minnesota based Somali community organization; New Americans Community Services (NACS) and the University of Minnesota. Using principles of community engagement; we conducted 23 key informant interviews to explore knowledge and barriers to cervical cancer screening among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota. The project was approved and monitored by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Together, the UMN research team and NACS created a list of 55 potential participants for the informant interviews. This list consisted of women who are known to offer health related guidance for the Somali community, and had some formal/informal leadership roles in the Somali community such as medical interpreters, community health care workers, or health care providers. The participants were 18 years and older and of Somali descent.

Key Informant interview procedure

The NACS team identified two bilingual and bicultural Somali staff to train as interviewers. They were trained by the University staff on the use of semi-structured question sets, probing on unanticipated issues, process of audio and written recording, and basics of community based participatory research methods. Participants filled out a demographic survey prior to or after each interview. In-person interviews followed a semi-structured method, including open-ended questions and further probing by interviewers. The goal for questions 1 and 2 was to explore Somali women's knowledge about what they considered important health issues for women. Questions 3, 4 and 5 were directed at the content areas which assessed knowledge surrounding cervical cancer and screening. Questions 6 and 7 assessed the screening barriers and facilitators. (Table 1)

Table 1. Topics Covered in the Key Informant Interview Guide.

|

Interviews were conducted in English, Somali, or both. Interviews were audio recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim thereafter. The interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes. Participants were reimbursed $50 for their time. Interviews were conducted between August 2011 and January 2012 and held in various community locations in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Data analysis

All interviews were tape-recorded. Interviews conducted in English were transcribed by Verbal Ink (http://verbalink.com/). The interviews conducted in Somali were transcribed by one of the Somali speaking research staff, and the transcription was checked against the audio file by a second Somali research staff. Based on the interview questions and probes, two coders from the university team reviewed each transcript independently and identified emergent themes and subthemes based on the interviewees' statements. The research team met on a regular basis to cross-check each transcript for accuracy and reliability and developed a coding scheme that was uniformly applied to each transcript to identify recurring themes. For each transcript the codes were compared for reliability. A difference in interpretation by the coders was reconciled by presenting the divergent views to the research team and the NACS team, who came to a consensus pertaining to these differences. The socio-ecological framework (Figure 1) was used during the analysis to help guide the interpretation and organization of the reported cervical cancer screening barriers.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 55 candidates initially identified, 23 participated in the interviews. More than half of the participants were between 26-45 years old; approximately half had lived in Minnesota for 10 years or more (Table 2).

Table 2. Participant Characteristics, N=23.

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | ≤25 | 6 (27%) |

| 26-45 | 13 (59%) | |

| ≥ 46 | 3 (13%) | |

| Years in MN | ≤ 10 | 10 (43%) |

| > 10 | 13 (57%) | |

| Highest grade level | < High school graduate or GED | 3 (13%) |

| ≥ High school graduate or GED | 20(87%) | |

Themes

We identified and grouped the barriers to cervical cancer screening under three socio-ecological levels; individual, community and system level (Figure 1). While some barriers overlap between categories, viewed collectively they provide a comprehensive framework on which to develop interventions that might address the complex obstacles surrounding cervical cancer screening. We will describe these multi-level screening barriers in detail below.

Individual barriers

Knowledge limitations

There was a general lack of knowledge around the benefits of cervical cancer screening. Many participants cited that individuals in the community did not feel a need to seek health nor see a need for a doctor if they were not sick. This presumption extended to multiple preventive health care services including breast and cervical cancer screening. Knowledge regarding risk factors for cervical cancer and the recommendation for cervical cancer screening was limited. Participants believed there was perception among individuals in the community that screening for cancer was unnecessary unless one was sick, experiencing vaginal bleeding, concerned with vaginal infection or had pain. There was limited distinction between standard gynecological cancer screening test and all other gynecological exams; it was reported that often a Somali woman might not know if she had undergone a cervical cancer screening test. Most participants indicated that screening was perceived as a sign of illness and the purpose was misinterpreted by many women.

Participants indicated that when they presented to clinics and were asked to undergo cervical cancer screening they did not know why the testing was necessary and often refused to do the screening tests. Most often they did not recognize themselves to be at risk for cervical cancer. The majority of women believed that a select number of women were perceived to be at risk for cervical cancer and this excluded women who were single, unmarried, divorced or older (Table 3; Quotes 1 & 2).

Table 3. Selected Quotes: Individual Barriers.

| Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Limitations | 1. We generally don't screen for anything, Somali's don't screen for anything. We don't believe in prevention. We think if we try to prevent something then we are actually chasing it, calling for it to happen. |

| 2. I don't think they have enough education or enough knowledge about cervical cancer. That is number one. | |

| Religion, fatalism | 3. If you ignore it and don't think about it and you pray to Allah, it won't happen to you. |

| 4. Either way you're gonna die the day you're supposed to die. | |

| Pain, fear and embarrassment | 5. Some of them believed that equipment would damage their baby productive ways. |

| 6. You know, if you cannot speak English well, and you ask to have an interpreter, sometimes interpreter could be a male. Sometimes interpreter could be someone you never meet before, and you just feel shame to ask, I want to check – I want to have, you know, check – I want to have somebody to check in my, you know, bottom. |

Religious beliefs

Religion plays a significant role within the Somali community; the majority of participants identify themselves as Muslim. Participants indicated that teachings in the Koran advocated for taking care of one's health, but at the same time everything that happens is understood to be under God's will. Prayer can help to keep one healthy and prevent illness. In addition prayer can help to heal. Religious individuals were perceived to be in good health. Accepting the will of God is important and many women reported that prevention has no impact because if God plans for someone to get sick, they will despite screening. Many people recognized cancer, similar to other illnesses as HIV/AIDS, as a type of punishment inflicted on the individual. Most women expressed a sense of fatalism; one was going to die the day they were supposed to die and participating in health prevention would not change this outcome (Table3; Quotes 3 & 4).

Pain, fear and embarrassment

The process of undergoing pelvic examination was perceived to be invasive and use of instruments such as a speculum was identified as a problem. Some individuals reported hearing women who declined Pap smear testing upon knowledge that a speculum was going to be inserted into the vagina. They believed that the equipment itself would damage reproductive organs or impact ability to carry a pregnancy in the future.

Other women perceived undergoing a Pap test as a sign of a problem or indication that a woman is unhealthy or possibly experiencing infection. It was also often stated that although religion itself did not prevent them from seeing a male physician they would prefer a female physician if available. A health care provider like them and a woman of color was perceived positively. Some of them explicitly stated that they would never undergo screening by a man. Although some participants understood the role of Pap test, they reported embarrassment and concern about how the community would interpret undergoing the examination because undergoing a gynecologic examination implies being sexually active (Table 3; Quotes 5 & 6).

Community barriers

Culture and modesty

Most women reported that sexuality is not an openly discussed topic among community members. They connected discussions about cervical cancer screening with sexual health. They described a community perception that if you undergo a Pap smear testing you must be sexually active, so the practice of cervical cancer screening was only openly allowed for married women.

The majority of women reported that circumcision is a barrier to cervical cancer screening both at an individual and community level. Although few participants mentioned its cultural significance, many identified that circumcision did prevent them from tolerating a pelvic exam. They reported a perception within the community that most women are circumcised and a pelvic exam was reported to be “culturally invasive”. Virginity is recognized as being very important in the Somali community and they reported that Pap tests for unmarried woman were not possible and unmarried women at any age would feel uncomfortable undergoing screening (Table 4; Quotes 1 & 2).

Table 4. Selected Quotes: Community Barriers.

| Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Culture and modesty | 1. Pap smear we don't see their importance because as a Somali woman – not only Somali woman, as a Muslim woman, we are not that much of active when it comes to sexuality. |

| 2. Even if she wanted to herself and she didn't care, she would be worried more about what the community feels about what she's doing rather than what is good for her | |

| Perception for unmarried, young and older women | 3. It would say 60 and over, they would think what the point is, I'm already 60 and over and in my dying stage. So they just focus on spirituality and doing whatever they can to be comfortable.” |

| 4. Because they think the minute you ask them to have the Pap smear, they think, “You are having sex. So then go and check yourself.” That's their interpretation of the Pap smear. | |

| Stigma of cancer | 5. It's looked down as like it's punishment or something like that. Many people think it's kind of like HIV/AIDS |

Perception for unmarried, young and older women

Sexual practices among younger woman were understood to be changing, however the overall community perception is that single women, divorced women, and older women do not need to undergo screening because they are not at risk for acquiring cervical cancer. Women from age 45 to 60 were described as “older” and therefore focused more on religious endeavors, so they were more likely to decline screening (Table 4; Quotes 3 & 4).

Stigma of Cancer

There was significant stigma related to cancer and people recognized that cancer was a difficult topic to discuss within the community. To some members in the community, cancer is understood to be a form of punishment from God. Individuals can be isolated from the community if they are sick from cancer. Some stated that they would rather die than know that they had cancer; they perceived cancer as a death sentence (Table 4; Quote 5).

Systems barriers

Language and logistic barriers

English is a second language for many Somali women and this remains a barrier to participation in screening, especially for older immigrants. Although many knew interpreter services were available, issues regarding trust in the interpreter, embarrassment around disclosing private issues to the interpreter, and the gender of the interpreter were identified as barriers. Participants reported a lack of time and competing demands on their time. In particular women often have multiple young children and have difficulties securing childcare and some lacked easy access to transportation. Participants indicated to us that women who did not possess health insurance find it challenging to participate in any health programs. Some women work part time and do not have insurance (Table 5; Quote 1 & 2).

Table 5. Selected Quotes: Systems Barriers.

| Quotes | |

|---|---|

| Logistical and language | 1. So language is always a problem, at least for the older women. |

| 2. Yes very much, because Somalis usually have a lot of children so she may have 4-5 kids and may not have chance to go. Even she may not get time to herself. | |

| Lack of trust in the healthcare system | 3. Our community, what I have seen so far, is we are a new immigrant. We don't know this system. And the health system is so huge. And we have a fear of going to people. |

| 4. They worry that they might take away their egg or something. They have their own way of picturing what is going to happen to them. |

Trust in the healthcare system

Lack of trust in the healthcare system and doctors is a major barrier to screening. Many participants questioned procedures that were recommended by physicians, and reported that they would often question all of the recommendations and second guess basic instructions. The health care system or the doctor was not perceived to be reliably operating to their benefit. Some reported that they would not follow the doctors' instructions without asking other women in the community if they should do so (Table 5; Quotes 3 & 4).

Discussion

Informant interviews conducted among Somali women in Minnesota revealed multiple barriers to cervical cancer screening. Using the socio-ecological framework to group the barriers, we were able to categorize them into three major levels, to make sense of which barriers overlap and at what levels (Figure 1).

The Somali community is a relatively close community and women share their encounters and experiences with family and friends. Some of these experiences have not been pleasant and have created a negative perception about the healthcare system. Some of these views are discussed by Carol and colleagues the discordant health beliefs and the divergent expectations [28]. Cultural beliefs and religious practices are a significant part of this community and the impact of religion advocating for healthy life style as well as an emphasis on the role of god and prayer in predicting one's health were clearly identified. Our findings are consistent with other studies that have reported on these views of religion, and modesty in regards to cervical cancer screening [18, 20, 21]. At the system level, our study participants indicated that the health care providers who do not share their similar religious beliefs find it hard to understand why the women decline to screen.

Fear, pain and embarrassment was specific at the individual level. Participants indicated that Somali women may share some health encounters and experiences with family and friends; however sexuality is not an openly discussed topic among community members. At the community level, overall the Somali women perceived the need for testing as a sign of poor health and or sexual activity outside of marriage. This perception in the community that older and divorced women are not at risk of cervical cancer creates stigma in the community resulting in some women choosing not to screen for fear of the community accusing them of being sexually active.

Participants indicated that the system based barriers are endemic to the complex US healthcare system. We concluded that a significant aspect of the lack of trust in the healthcare system was a result of the challenges Somali women experience in communicating with the healthcare providers despite the presence of interpreters. The interpreter is critical to navigating the health care system. In this close knit community, the women are not sure if their information is safe with the interpreters, thus they tend to avoid the seeking healthcare services all together unless they are ill. The language barriers reported by our participants are consistent with those reported in another study where women's experiences interacting with the healthcare system were unpleasant and thus created a negative perception about the Western healthcare system for these women [28].

We believe that one of the ways to address English language as a barrier; is to develop programs that address this barrier at all levels. At the individual level, we will need to provide language appropriate messages that address cervical cancer and screening services. At the community level we will need to address the prevailing stigma surrounding sexual health and at the systems level, we will need to engage with all healthcare providers and develop ways to appropriately address cancer screening for communities that are not proficient in English.

A limitation of these data is that the Somali immigrant community in Minnesota may not be representative of the Somali immigrant population in the US; however the Minnesota Somali immigrant community is the largest in the country [29, 30]. In addition, the study selected informants who were more educated than the average Somali immigrant woman, as a result the information they provided may not be representative for those with a lower education level. However, we believe that to who participated provided us with views their own views and those from the community, since they were chosen to participate in the study based on their leadership roles and knowledge of the community practices.

Also, the interview topic was sensitive in nature, including exploration of women's sexual health, therefore there may be components of screening behavior that could not be fully ascertained using this method. The data are descriptive and therefore there is no basis for inferring causality.

Implications

Our study findings are supportive of an approach to cervical cancer prevention and overall women's health that engages on community, individual and health care system levels. There are barriers that were specific to a woman's knowledge around her individual risk factors. These were compounded by the community's inaccurate perception of risk. Thus any approaches to intervention would have to design solutions that target multiple levels. Knowledge of cultural barriers as well as issues around modesty and sexual practices are needed as health care systems and practitioners engage Somali women in cervical cancer prevention. Non-traditional, innovative methods of cervical cancer screening that do not require a pelvic exam and Pap testing may be applicable to this community.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute: Minnesota Community Networks Center for Eliminating Cancer Disparities (U54CA153603) and Cancer-related Health Disparities Education and Career Development Program (1R25CA163184). Special thanks to the Somali immigrant women for volunteering to participate in this study. We also thank the staff members of the New Americans Community Services team who aided in the recruitment and moderating the interviews.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

Conflict of interest statement: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, S H, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers CD, Parkin D. GLOBO-CAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer- Base No. 10. 2008 [Internet]. from Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Sitas F, Chirenje M, Stein L, Abratt R, Wabinga H. Part I: Cancer in Indigenous Africans--burden, distribution, and trends. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization; 2012. Globocan 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2014, from http://globocan.iarc.fr/ia/World/atlas.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Census Bureau. U.S. Immigration: National and State Trends and Actions. U.S. Census Working Paper No.81, “Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000,” Table 14: Nativity of the population, for regions, divisions, and states: 1850 to 2000. 2013 Retrieved January 15, 2014, from http://www.pewstates.org/research/data-visualizations/us-immigration-national-and-state-trends-and-actions-85899500037.

- 6.Department., U. S. S. Bureau of Population Refugees, and Migration Washington DCRefugee Admissions Program for Africa. 2013 Retrieved June, 2014, from http://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/onepagers/202626.htm#.

- 7.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MMWR. 3. Vol. 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Cancer screening—United States, 2010; p. 4145. from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/screening.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2012 Retrieved February 2014 from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-031941.pdf.

- 11.Khadilkar A, Chen Y. Rate of cervical cancer screening associated with immigration status and number of years since immigration in Ontario, Canada. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(2):244–248. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsui J, Saraiya M, Thompson T, Dey A, Richardson L. Cervical cancer screening among foreign-born women by birthplace and duration in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(10):1447–1457. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrasquillo O, Pati S. The role of health insurance on Pap smear and mammography utilization by immigrants living in the United States. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echeverria SE, Carrasquillo O. The roles of citizenship status, acculturation, and health insurance in breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrant women. Med Care. 2006;44(8):788–792. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215863.24214.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harcourt N, Ghebre RG, Whembolua GL, Zhang Y, Warfa Osman S, Okuyemi KS. Factors Associated with Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Behavior Among African Immigrant Women in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison TB, Wieland ML, Cha SS, Rahman AS, Chaudhry R. Disparities in preventive health services among Somali immigrants and refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):968–974. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, Volpe E, Diaz K, Omar S. Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and preventive health care among somali women in the United States. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(4):360–380. doi: 10.1080/07399330601179935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdullahi A, Copping J, Kessel A, Luck M, Bonell C. Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health. 2009;123(10):680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redwood-Campbell L, Fowler N, Laryea S, Howard M, Kaczorowski J. ‘Before you teach me, I cannot know’: immigrant women's barriers and enablers with regard to cervical cancer screening among different ethnolinguistic groups in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(3):230–234. doi: 10.1007/BF03404903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Amoudi S, Canas J, Hohl SD, Distelhorst SR, Thompson B. Breaking the Silence: Breast Cancer Knowledge and Beliefs Among Somali Muslim Women in Seattle, Washington. Health Care Women Int. 2013 doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.857323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, Gipson T, Volpe E, Jean-Pierre P. Caring for Somali women: implications for clinician-patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health program planning: an educational and ecological approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nuss HJ, Williams DL, Hayden J, Huard CR. Applying the Social Ecological Model to evaluate a demonstration colorectal cancer screening program in Louisiana. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1026–1035. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daley E, Alio A, Anstey EH, Chandler R, Dyer K, Helmy H. Examining barriers to cervical cancer screening and treatment in Florida through a socio-ecological lens. J Community Health. 2011;36(1):121–131. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae SS, Jo HS, Kim DH, Choi YJ, Lee HJ, Lee TJ. Factors associated with gastric cancer screening of Koreans based on a socio-ecological model. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41(2):100–106. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.2.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pavlish CL, Noor S, Brandt J. Somali immigrant women and the American health care system: discordant beliefs, divergent expectations, and silent worries. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grieco EM, Rytina NF. US data sources on the Foreign Born and Immigration. International Migration Review. 2011;45(4):1001–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronningen B. Estimates of Selected Immigrant Populations in Minnesota: Minnesota State Demographic Center 2004 [Google Scholar]