Abstract

The peroneocuboid joint, between the peroneus longus tendon and the cuboid bone, has not been anatomically well-defined and no embryological study has been published. Furthermore, the ossification of the os peroneum (a sesamoid inside the peroneus longus tendon) and its associated pathology has been considered to be generated by orthostatic and/or mechanical loads. A light microscopy analysis of serially sectioned human embryonic and fetal feet, the analysis of human adult feet by means of standard macroscopic dissection, X-ray and histological techniques have been carried out. The peroneus longus tendon was fully visible until its insertion in the 1st metatarsal bone already at embryonic stage 23 (56–57 days). The peroneocuboid joint cavity appeared at the transition of the embryonic to the fetal period (8–9th week of gestation) and was independent of the proximal synovial sheath. The joint cavity extended from the level of the calcaneocuboid joint all the way to the insertion of the peroneus longus tendon in the 1st metatarsal bone. The frenular ligaments, fixing the peroneus longus tendon to the 5th metatarsal bone or the long calcaneocuboid ligament, developed in the embryonic period. The peroneus longus tendon presented a thickening in the area surrounding the cuboid bone as early as the fetal period. This thickening may be considered the precursor of the os peroneum and was similar in shape and in size relation to the tendon, to the os peroneum observed in adults. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that the os peroneum, articular facets of the peroneus longus tendon and cuboid bone, the peroneocuboid joint and the frenular ligaments appear during the embryonic/fetal development period and therefore they can not be generated exclusively by orthostatic and mechanical forces or pathological processes.

Keywords: cuboid, foot development, os peroneum, peroneus longus, sesamoid

Introduction

The anatomy of the area surrounding the lateral aspect of the cuboid bone, where the peroneus longus tendon bends plantarwards and medially towards its insertion in the first metatarsal bone, has been subjected to different types of studies, but the pathological entities reported are still sometimes confusing or controversial (Sobel et al. 1994).

Anatomical and radiological studies have shown that a sesamoid bone, known as the os peroneum, may be present in up to 30% of peroneus longus tendons as either a single bone, bipartite or multipartite (Pfitzner, 1892, 1896; Bizarro, 1921; Holland, 1921; Burman & Lapidus, 1931; Siecke, 1964; LeMinor, 1987; Cilli & Akcaoglu, 2005; Coskun et al. 2009; Muehleman et al. 2009); anatomical and histological studies have confirmed that up to 55% or more of this sesamoid bone may also present in a non-ossified cartilagenous state (Picou, 1894a; Parsons & Keith, 1897; Drexler, 1958; Leutert, 1958; Benjamin et al. 1995; Benjamin & Ralphs, 1998; Oyedele et al. 2006; Patil et al. 2007). Furthermore, fixing ligaments/bands called frenular ligaments, which extend from the peroneus longus tendon to surrounding tissues, have been described (Stieda, 1889a,b,c; Picou, 1894b; LeDouble, 1897; Wildenauer & Muller, 1951; Drexler, 1958; Patil et al. 2007) and a peroneocuboid joint has even been described (Ebraheim et al. 1999).

The origin of the sesamoid bone or its fibrocartilage substitute has been subject to controversy (LeMinor, 1987) but current opinion is that its origin is related to mechanical forces. In the adult, the tendons of the peroneous longus are subjected to mechanical forces resulting from muscle contraction and also from the orthostatic pressure exerted by body weight (Leutert, 1960). In contrast, during gestation, the only mechanical forces are those exerted by muscle contraction. Furthermore, it was stated that muscle contraction starts during the 2nd month of pregnancy (Starck, 1955), i.e. at the 8–9th week or beginning of the fetal period of development (Patten, 1968; O'Rahilly & Müller, 1987). To the best of our knowledge, no study of the embryonic–fetal development of this area has been carried out.

Therefore, the aim of the current work was to establish whether the structure of the os peroneum, the peroneocuboid joint and the frenular ligaments are already present in the pre-orthostatic load period, the embryonic–fetal period, and therefore its existence would be determined not only by mechanical forces but perhaps genetically.

Material and methods

Two different human samples were analysed: embryonic/fetal and adult. A total of six embryos (stages 20–22) and 17 fetuses (9–32 weeks) belonging to our department collection were used for this study; they were serially sectioned in different axes and stained with different techniques (Bielschowsky, Haematoxylin-eosin, Azan, Mason's trichromic, VOF). Embryos were classified according to the stages defined by O'Rahilly & Müller (1987) and fetuses by stages defined by Patten (1968) (Table 1). The sections were analysed with a standard light microscope attached to a digital camera for picture acquisition.

Table 1.

Details of the embryos and fetuses included in the current work

| Name | No. | Stage (O'Rahilly & Müller) | C-R length (mm) | Age of gestation (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | 1 | Stage 20 | 21 | 50–51 |

| E2 | 1 | Stage 21 | 24 | 52 |

| E3 | 1 | Stage 22 | 25 | 54 |

| E4 | 1 | Stage 22 | 25 | 54 |

| E5 | 1 | Stage 22 | 25 | 54 |

| E6 | 1 | Stage 22 | 27 | 54 |

| Name | No. | Stage (O'Rahilly & Müller) | Patten30 (mm) | Age of gestation (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1 | 32 | 9 | |

| F2 | 1 | 34 | 9 | |

| F3 | 1 | 37 | 9 | |

| F4 | 2 | 37 | 9 | |

| F5 | 1 | 41 | 9 | |

| F6 | 2 | 42 | 9 | |

| F7 | 1 | 44 | 9 | |

| F8 | 2 | 55 | 10 | |

| F9 | 2 | 76 | 11 | |

| F10 | 2 | 100 | 13 | |

| F11 | 2 | 110 | 14 | |

| F12 | 2 | 116 | 14 | |

| F13 | 1 | 131 | 15 | |

| F14 | 2 | 140 | 16 | |

| F15 | 1 | 150 | 17 | |

| F16 | 1 | 177 | 19 | |

| F17 | 1 | 332 | 32 |

No., number of feet studied; C-R, crown–rump length.

The embryos and fetuses were obtained with parental consent according to current law. A second sample consisting of 38 (18 right, 20 left) (14 male, six female) human adult cadaveric feet with an age ranging between 65 and 90 years (mean age = 79; standard deviation = 7.99) were dissected to study the presence of the anterior and/or posterior frenular ligaments, the presence of a thickening in the peroneus longus tendon and the existence of an articular surface in the cuboid bone. After dissection and documentation, the tendons were removed and subjected to X-ray to differentiate the ossified from the non-ossified os peroneum. The tendons with a non-ossified os peroneum were embedded, sectioned and stained with standard histological techniques (Haematoxylin-eosin, Azan, Mason's trichromic).

The adults donated their bodies during life according to current regulations for body donation. Statistical comparisons were made using the chi-squared test (P < 0.005).

Results

Study of embryos and fetuses

During the embryonic period of development, the peroneus longus tendon on the lateral aspect of the cuboid could be detected in one embryo as early as stage 21 (24 mm; 52 days). It appeared as a condensation next to the cuboid bone (Fig. 1A,B); the cuboid bone at this stage was clearly visible in a form closely similar to the final form in the adult (Fig. 1A). The peroneus longus tendon could not be followed to its final insertion into the first metatarsal bone.

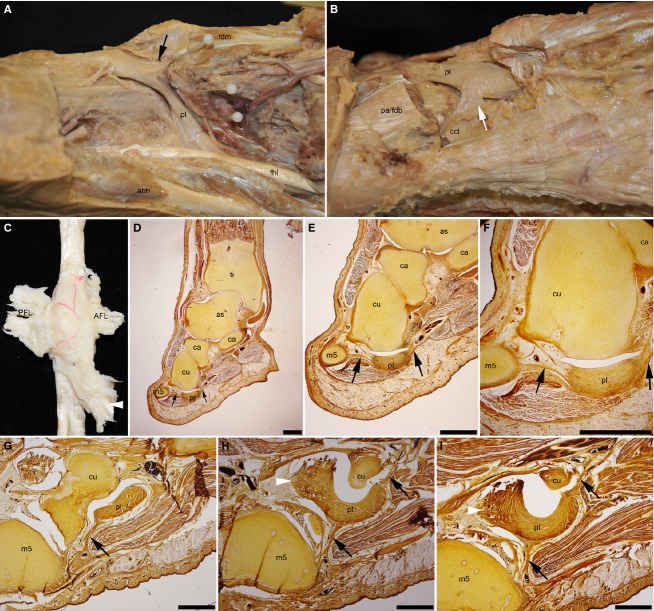

Fig. 1.

Developmental stages of the peroneocuboid joint. (A) Stage 21 embryo, note the tendon of the peroneus longus next to the cuboid bone as a tissue condensation (arrowhead). Note also fibres of the developing abductor digiti minimi (arrows). (B) Magnification of the square in (A). (C) Transversal sections of a stage 22 embryo. Note the completed development of the peroneus longus tendon inserting into the metatarsal bone (arrowhead), and additionally into the first interosseous muscle (arrowhead). (D) Magnification of the square in (C). (E) Transversal/oblique section of a late stage 23 embryo showing already a peroneocuboid joint (arrowhead) and a posterior frenular ligament (arrow). (F) Magnification of the square in (E). (G) Sagittal section of a 9-week-old (34-mm) fetus showing the regression of the tissue between the cuboid bone and the peroneus longus tendon. (H) Magnification of the square in (G. (I) Sagittal section of 9-week-old (37-mm) fetus showing the direct contact between the peroneus longus tendon and the cuboid bone (arrowhead). (J) Magnification of the square in (I). (K) Sagittal section of a 17-week-old fetus showing a completed, adult-like peroneocuboid joint (arrowhead). (L) Magnification of the square in (K). Scale bars: 1000 μm (A,C,E,G,I,K); 100 μm (B,D,F,H,J,L). Ti, tibia; fi, fibula; as, astragalus; Ca, calcaneus; Cu, cuboid bone; c1-c2-c3, first, second and third cuneiform bones; m1–m5, first to fifth metatarsal bone; pl, peroneus longus tendon; adm, abductor digiti minimi muscle.

Before the end of the embryonic period (stages 23), the peroneus longus tendon could be followed from its origin, all the way until its insertion into the first metatarsal bone in all four embryos (Fig. 1C,D). Afterwards, in the transition from the embryonic to the fetal period of development, the formation of a full cavity could be observed in the medial aspect of the peroneous longus tendon (Fig. 1E,F). This cavity extended to the anterior and posterior borders of the peroneous longus tendon but not to the lateral side of the tendon (Fig. 1E,F). At the beginning of the fetal period (9th week of gestation), the cavity increased in size and came in direct contact with the surface of the cuboid bone (Fig. 1G,H). With increasing age of gestation, the cavity increased in size and the tissue surrounding it increased in thickness. The surface of the cuboid bone facing the peroneous longus tendon was devoid of the normally fibrous tissue surrounding the cuboid bone already in 37-mm fetuses (9 weeks) (Fig. 1I,J). The surface of the peroneus longus tendon facing the cuboid bone presented a clearly differentiated layer of fibrous or fibrocartilaginous tissue already in 150-mm fetuses (17 weeks) and older fetuses (three specimens) (Fig. 1K,L).

Proximally, the peroneocuboid joint extended to the level of the calcaneo-cuboid joint (Fig. 2A,B) and distally, all the way to its insertion into the first metatarsal bone (Fig. 2C,D). This cavity is never in contact with the proximal sinovial sheath (Fig. 2A,B).

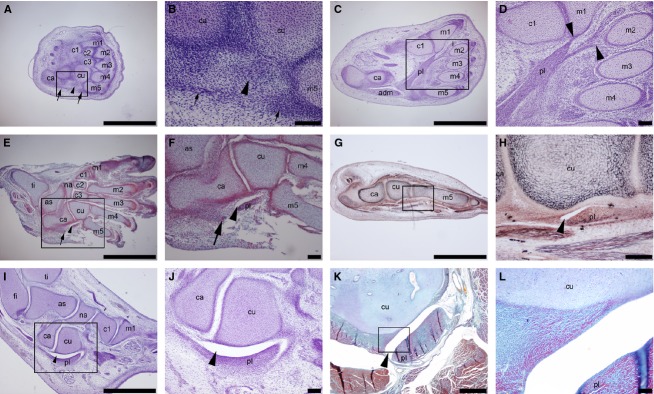

Fig. 2.

Limits of the peroneocuboid joint in fetal feet. (A) Sagittal sections; note the separation between the proximal synovial sheath (arrow) and the peroneocuboid joint (arrowhead). (B) Magnification of the square in (A). (C) Frontal sections; note the insertion of the peroneus longus tendon into the first metatarsal head and how the peroneocuboid joints reached to this insertion point (arrowheads). (D) Magnification of the square in (C). Scale bars: 1000 μm (A,C,D); 100 μm (B). fi, fibula; Ca, calcaneus; Cu, cuboid bone; c1-c2-c3, first, second and third cuneiform bones; m1–m5, first to fifth metatarsal bone; pl, peroneus longus tendon; adm, abductor digiti minimi muscle; fdm, flexor digiti minimi muscle; fdl, flexor digitorum longus muscle; fdb, flexor digitorum brevis muscle; adh, adductor hallucis muscle; fhl, flexor hallucis longus tendon; fhb, flexor hallucis brevis muscle; abh, abductor hallucis muscle.

The peroneus longus tendon at the level of cuboid bone can be fixed to surrounding tissues by fibrous/tendinous bands termed frenular ligaments (Fig. 3). The anterior frenular ligament joined the peroneus longus tendon to the fifth metatarsal bone (Fig. 3A,B), whereas the posterior frenular ligament joined the peroneus longus tendon to the long calcaneo-cuboid ligament or the lateral and deep fascia of the flexor digitorum brevis muscle (Fig. 3A,C). Additional attachments to the fourth dorsal interosseous or the flexor digiti minimi were observed (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Morphology of the frenular ligaments. (A) Plantar view of a right adult foot showing an anterior frenular ligament (black arrow) (B) Plantar view of a right adult foot showing a posterior frenular ligament (white arrow). (C) Adult peroneus longus tendon extracted from a right foot showing anterior (AFL) and posterior frenular ligaments (PFL) as well as an additional insertion into the interosseous muscle (white arrowhead). (D-F) Sagittal/oblique section of a fetal foot showing the anterior and posterior frenular ligament (black arrows). (G-I) Serial transversal sections of a fetal foot showing the anterior and posterior frenular ligaments (black arrows) as well as an additional insertion into the interosseous muscle (white arrowhead). Scale bars: 1000 μm (D-I). ti, tibia; Ca, calcaneus; Cu, cuboid bone; m5, fifth metatarsal bone; pl, peroneus longus tendon; fdm, flexor digiti minimi muscle; fdb, flexor digitorum brevis muscle; pa, plantar aponeurosis; ccl, calcaneo-cuboid ligament; fhl, flexor hallucis longus tendon; abh, abductor hallucis muscle.

The development of these frenular ligaments and additional attachments started simultaneously with the development of the main tendinous mass. So, at embryonic stage 23 the frenular ligaments were already visible emerging from the anterior or posterior borders of the peroneus longus tendon. During the fetal period these frenular ligaments could be observed increasing in thickness and showing a histological appearance similar to that of the main tendinous mass (Fig. 3D–I). The transversal section of the main tendinous mass was not homogeneous along its course; an increase in width of the tendon at the level of the peroneocuboid joint was detectable (Fig. 3D).

Anatomical, radiological and histological study of adult feet

From the total number of specimens studied, 37 feet (the total sample included 38 feet but one was damaged due to previous dissection and was excluded from the study), only the anterior frenular ligament was present in 29.7% (Fig. 3A), only the posterior frenular ligament in 5.4% (Fig. 3B), and both were present simultaneously in 59.5% (Fig. 3C) (Table 2). The morphology of these ligaments varied from thin fibrous bands to broad and thick expansions to the surrounding structures.

Table 2.

Incidence of anterior (AFL) and posterior frenular ligaments (PFL) in association with an ossified or fibrocartilaginous os peroneum (OP)

| No AFL No PFL | AFL | PFL | APF+PFL | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ossified OP | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 11 (29.7%) |

| Fibrocartilaginous OP | 1 | 9 | 0 | 16 | 26 (70.3%) |

| Total | 2 (5.4%) | 11 (29.7%) | 2 (5.4%) | 22 (59.5%) | 37 (100%) |

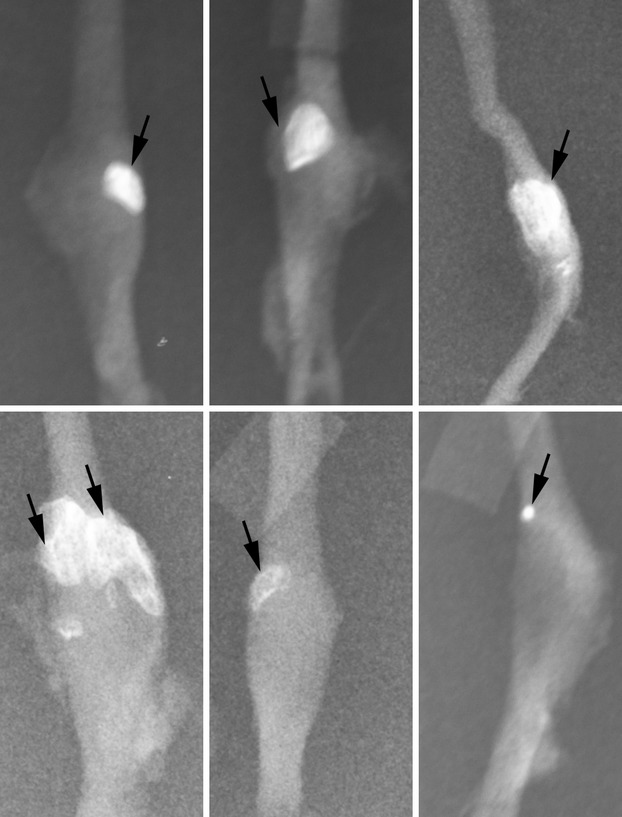

The os peroneum, a sesamoid inside the peroneus longus tendon mass, was present in an ossified state in 29.7% (Fig. 4) and in the remaining cases as a non-ossified state (70.3%), both confirmed macroscopically as a thickening of the peroneus longus tendon and histologically (Fig. 5). The ossified os peroneum showed a range of shapes and sizes and small calcifications were observed in areas outside the tendon bending (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

X-ray caption of isolated adult peroneus longus tendons. Note the variety of sizes and forms as well as location of the ossified/calcified tissue.

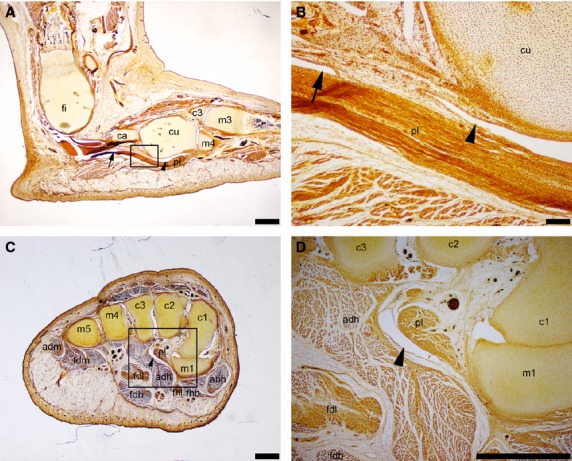

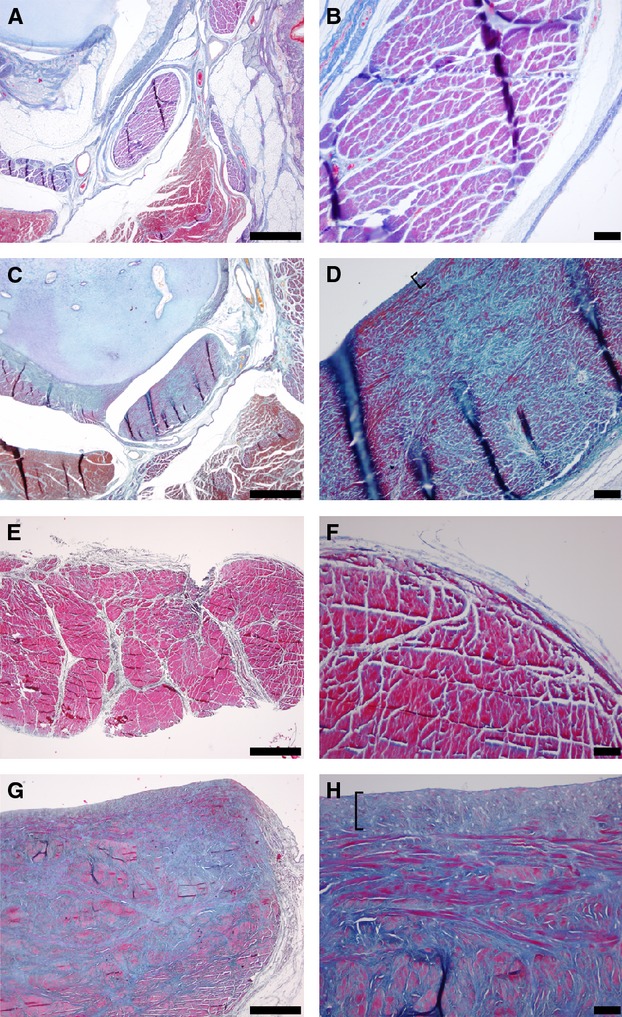

Fig. 5.

Histological sections of the peroneus longus tendon proximal to the peroneocuboid joint (A,B,E,F) and at peroneocuboid joint level (C,D,G,H); Fetal (A-D) and adult feet (E-H). Note the increased amount of elastic fibres (blue staining) surrounding the collagen fibres (red staining) in both fetal and adult feet at peroneocuboid level (C,D,G,H) in comparison with the lack of such fibres in the proximal tendon (A,B,E,F). Note also the articular surface of the peroneus longus tendon in the side that faces the cuboid bone (brackets in D and H). Scale bars: 1000 μm (A,C,E,G); 100 μm (B,D,F,H).

The chi-squared test showed no correlation between the presence of the frenular ligaments and the presence or absence of an ossified os peroneum (P < 0.005) (Table 2).

The histological study confirmed that the non-ossified os peroneum corresponded to an area of fibrous or fibrocartilaginous tissue within the peroneous longus tendon with increased elastic fibres when compared with the structure of the tendon proximally (Fig. 5). Furthermore, a thin fibrous or fibrocartilaginous layer could be detected at its surface in contact with the cuboid bone not only in all adult samples (Fig. 5H) but also in all fetuses older than 17 weeks (Fig. 5D). The cuboid bone presented an articular facet for the peroneus longus tendon in all cases.

Discussion

The type of study carried out in the current work is highly reliable in confirming the existence and extension of the peroneocuboid joint in an undisturbed setting, as no dissection was carried out in the area (Ebraheim et al. 1999) and no disturbances could have been caused by the histological acquisition of samples used. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to shown that the peroneocuboid joint is formed during the embryonic period, just when movement has been stated to start (Starck, 1955). The development of this joint is completed during the fetal period. The joint cavity extends proximally to the level of the calcaneo-cuboid joint and distally all the way to the insertion point of the peroneus longus tendon in the first metatarsal bone. It is also demonstrated that this joint is independent from the proximal synovial sheath, as previously reported (Leutert, 1955; Ebraheim et al. 1999); this may have clinical implications in the pathological processes observed in this area. It is therefore important to bear in mind the existence of this joint, as it may be subjected to have a distinct pathology from that affecting synovial sheaths. This morphological detail may explain some of the different pathological situations described in this area and that have remained obscure/controversial.

The current study expands on the former concepts and demonstrates that a fibrous/fibrocartilaginous os peroneum or thickening of the peroneus longus tendon is already present during embryonic and/or fetal development, and therefore its presence in the adult can not be exclusively the result of mechanical forces related to weight-bearing/walking, as these forced do not exist during gestation. The ossification of the os peroneum may be related to mechanical forces, but neither previous studies nor the current work could elucidate this fact and this remains to be determined with specific studies. A previous radiological study indicated that the ossified os peroneum was more frequently detected radiologically with increasing age (Bizarro, 1921; Siecke, 1964).

The anatomical details of the frenular ligaments or os peroneum found in adults are generally in accordance with those previously reported, except for a higher incidence of the posterior frenular ligament and ossified os peroneum than in previous studies (Picou, 1894b; LeDouble, 1897; Patil et al. 2007); this may be explained by the morphology observed, including thin fibrous bands to thick and broad bands, making it therefore difficult to classify them as ligaments or not. The differences regarding the ossified os peroneum may be due to the fact that the X-rays were taken on excised tendons and not on complete feet, and therefore there is no masking of small calcifications as may be found in living subjects (Siecke, 1964), but our results are in overall accordance with those obtained in similar studies (Muehleman et al. 2009).

In contrast to previous works, the current study presents a composite study of all structures, whereas previous work only analysed single features. This enabled us to dismiss the idea that a relationship may exist between the presence or absence of an os peroneum and the frenular ligaments (Drexler, 1958).

The high incidence of the different morphological structures (frenular ligaments, ossified and non-ossified os peroneum) described in this study makes them relevant when analysing patients presenting lateral foot pain and should be kept in mind when making diagnosis and decisions on repair of a peroneal tendon rupture.

A clinical sign of peroneus longus tear is the proximal migration of the os peroneum (Mains & Sullivan, 1973; Tehranzadeh et al. 1984; Cachia et al. 1988; Bianchi et al. 1991; Bloom, 1991; Blitz & Nemes, 2007; Sammarco et al. 2010). However, taking into consideration that the frenular ligaments are very common, a peroneus longus tear may be present without migration of the os peroneum, as this may be fixed by the frenular ligaments, especially if the tear occurs distal to the os peroneum, as previously described (Peacock et al. 1990).

The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), scintigraphy or ultrasound has proven useful in imaging this area and for differential diagnosis (Crain & El-Khoury, 1989; Lazos, 1995; Rademaker et al. 2000; Okazaki et al. 2003; Brigido et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2005; Zgonis et al. 2005; Fernandes et al. 2007; Sammarco et al. 2010; Sofka et al. 2010; Chadwick et al. 2011). The variety of pathological entities described in this area include fracture of the os peroneum (Stropeni, 1920; Hadley, 1942; Brav & Chewning, 1949; Grisolia, 1963; Peacock et al. 1986; Wilson & Moyles, 1987; Cachia et al. 1988; Pessina, 1988; Hogan, 1989; Peterson & Stinson, 1992; Wander et al. 1994; MacDonald & Wertheimer, 1997; Bessette & Hodge, 1998; Requejo et al. 2000; Okazaki et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2011), hypothetical fracture of the cuboid bone (Haguier, 1937; Ginieys, 1939), peroneus longus tendon rupture (Burman, 1956; Evans, 1966; Davies, 1979; Peacock et al. 1986; Thompson & Patterson, 1989, 1990; Pai & Lawson, 1995; Sammarco, 1995; Truong et al. 1995; Patterson & Cox, 1999; Rademaker et al. 2000), os peroneum friction syndrome (Bashir et al. 2009), degenerative arthritis (Resnick et al. 1977; Burton & Altman, 1986), acute calcific tendinitis of peroneus longus (Cox & Paterson, 1991), peroneus longus stenosing tenosinovitis (Pierson & Inglis, 1992; Bruce et al. 1999), cuboid oedema associated with peroneus longus tendinopathy (O'Donnell & Saifuddin, 2005) and nerve entrapment (Perlman, 1990; Sobel et al. 1994). A painful os peroneum syndrome has been defined (Sobel et al. 1994; Mellado et al. 2003; Vancauwenberghe et al. 2009; Jeppesen et al. 2011), although it was stated that sesamoid bones are only painful if subjected to trauma (Kruse & Chen, 1995).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Alicia Cerro and María Dolores Arroyo for their excellent technical assistance during the acquisition of histological sections. This research was supported by funds obtained through postgraduate training courses by the UCM920547 Group.

Author contributions

Study design: M. Rodriguez-Niedenführ, V. Guimera and T. Vazquez. Acquisition of data: A. Lafuente, L. Zambrana, V. Guimera. Data interpretation: J. R. Sanudo, M. Rodriguez-Niedenführ, A. Lafuente, L. Zambrana, V. Guimera and T. Vazquez. Drafting of the manuscript: M. Rodriguez-Niedenführ, T. Vázquez, J. R. Sanudo. Critical revision of the manuscript: M. Rodriguez-Niedenführ, T. Vázquez. Approval of the article: V. Guimerá, A. Lafuente, L. Zambrana, M. Rodriguez-Niedenführ, J. R. Sañudo and T. Vazquez.

References

- Bashir WA, Lewis S, Cullen N, et al. Os peroneum friction syndrome complicated by sesamoid fatigue fracture: a new radiological diagnosis? Case report and literature review. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin M, Ralphs JR. Fibrocartilage in tendons and ligaments – an adaptation to compressive load. J Anat. 1998;193:481–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19340481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin M, Qin S, Ralphs JR. Fibrocartilage associated with human tendons and their pulleys. J Anat. 1995;187:625–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessette BJ, Hodge JC. Diagnosis of the acute os peroneum fracture. Singapore Med J. 1998;39:326–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S, Abdelwahab IF, Tegaldo G. Fracture and posterior dislocation of the os peroneum associated with rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1991;42:340–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizarro AH. On sesamoid and supernumerary bones of the limbs. J Anat. 1921;55:256–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz NM, Nemes KK. Bilateral peroneus longus tendon rupture through a bipartite os peroneum. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;46:270–277. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom RA. The infracalcaneal os peroneum. Acta Anat. 1991;140:34–36. doi: 10.1159/000147034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brav EA, Chewning JB. Fracture of the os peroneum: a case report. Milit Surg. 1949;105:369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigido MK, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, et al. Radiography and US of os peroneum fractures and associated peroneal tendon injuries: initial experience. Radiology. 2005;237:235–241. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce WD, Christofersen MR, Phillips DL. Stenosing tenosynovitis and impingement of the peroneal tendons associated with hypertrophy of the peroneal tubercle. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:464–467. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman M. Subcutaneous tear of the tendon of the peroneus longus. Its relation to the giant peroneal tubercle. Arch Surg. 1956;73:216–219. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280020030006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman MS, Lapidus PW. The functional disturbances caused by the inconstant bones and sesamoids of the foot. Arch Surg. 1931;22:936–975. [Google Scholar]

- Burton SK, Altman MI. Degenerative arthritis of the os peroneum: a case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1986;76:343–345. doi: 10.7547/87507315-76-6-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachia VV, Grumbine NA, Santoro JP, et al. Spontaneus rupture of the peroneus longus tendon with fracture of the os peroneum. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1988;27:328–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick C, Highland AM, Hughes DE, et al. The importance of magnetic resonance imaging in a symptomatic ‘bipartite’ os peroneum: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:82–86. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilli F, Akcaoglu M. The incidence of accessory bones of the foot and their clinical significance. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2005;39:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun N, Yuksel M, Cevener M, et al. Incidence of accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones in the feet: a radiographic study of the Turkish subjects. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s00276-008-0383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Paterson FWN. Acute calcific tendinitis of peroneus longus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:342. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain MR, El-Khoury GY. Stress fracture of the os peroneum (letter) AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:430. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.2.430-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JAK. Peroneal compartment syndrome secondary to rupture of the peroneus longus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:783–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler L. Fixation der Sehne der M. peroneus longus und Os peronaeum. Acta Anat. 1958;35:345–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ebraheim NA, Lu J, Haman SP, et al. Cartilage and synovium of the peroneocuboid joint: an anatomic and histological study. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:108–111. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD. Subcutaneous rupture of the tendon of peroneus longus. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:507–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R, Aguiar R, Trudell D, et al. Tendons in the plantar aspect of the foot: MR imaging and anatomic correlation in cadavers. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginieys L. Fracture isolée d'un os surnuméraire du tarse (os peroneum). Traitement par l'infiltration novocainique. Rev Orthop. 1939;26:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Grisolia A. Fracture of the os peroneum. Clin Orthop. 1963;28:213–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley HG. Unusual fracture of sesamum peroneum. Radiology. 1942;38:90. [Google Scholar]

- Haguier P. Fracture isolee d'un oselet surnummeraire du tarse (os peroneum) Rev Orthop. 1937;24:356–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan JF. Fracture of the os peroneum. Case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1989;79:201–204. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-4-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CT. On rarer ossifications seen during x-ray examinations. J Anat. 1921;55:235–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen JB, Jensen FK, Falborg B, et al. Bone scintigraphy in painful os peroneum syndrome. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:209–211. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318208f349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse RW, Chen J. Accessory bones of the foot: clinical significance. Mil Med. 1995;160:464–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazos EA. Commentaries on ‘Rupture of the peroneus longus tendon by Pai VS, Lawson D’. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1995;34:510. doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(09)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDouble AF. Traité des variations du système musculaire de l'homme et de leur signification au point de vue de l'anthropoligie et zoologique. Paris: Schleicher Frères; 1897. [Google Scholar]

- LeMinor JM. Comparative anatomy and significance of the sesamoid bone of the peroneus longus muscle (os peroneum) J Anat. 1987;151:85–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutert G. Über den Bau der Sehne des M. fibularis longus im Bereich des äusseren Fussrandess. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch. 1955;61:512–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutert G. Über den histologischen Aufbau des Os peroneaum. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch. 1958;64:639–651. [Google Scholar]

- Leutert G. Über die Entwicklung der Struktur der Sehne des Musculus peronaeus longus. Anat Anz. 1960;108:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BD, Wertheimer SJ. Bilateral os peroneum fractures: comparison of conservative and surgical treatment and outcomes. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36:220–225. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(97)80119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains DB, Sullivan RC. Fracture of the os peroneum. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:1529–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado JM, Ramos A, Salvado E, et al. Accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones of the ankle and foot: imaging findings, clinical significance and differential diagnosis. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:164–177. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehleman C, Williams J, Bareither ML. A radiologic and histologic study of the os peroneum: prevalence, morphology, and relationship to degenerative joint disease of the foot and ankle in a cadaveric sample. Clin Anat. 2009;22:747–754. doi: 10.1002/ca.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell P, Saifuddin A. Cuboid oedema due to peroneus longus tendinopathy: a report of four cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0907-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Nakashima S, Nomura S. Stress fracture of an os peroneum. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:654–656. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rahilly R, Müller F. Developmental Stages in Human Embryos. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Oyedele O, Maseko C, Mkasi N, et al. High incidence of the os peroneum in a cadaver sample in Johannesburg, South Africa: possible clinical implications? Clin Anat. 2006;19:605–610. doi: 10.1002/ca.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai VS, Lawson D. Rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1995;34:475–477. doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(09)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons FG, Keith A. Seventh report of the committee of collective investigation of the Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, for the year 1896–97. J Anat. 1897;32:164–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil V, Frisch NC, Ebraheim NA. Anatomical variations in the insertion of the peroneus (fibularis) longus tendon. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:1179–1182. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten BM. Human Embryology. 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson MJ, Cox WK. Peroneus longus tendon rupture as a cause of chronic lateral ankle pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;365:163–166. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199908000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock KC, Resnick EJ, Thoder JJ. Fracture of the os peroneum with rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;202:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock KC, Resnick EJ, Thoder JJ. Rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. Report of three cases (letter) J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman MD. Os peroneum fracture with sural nerve entrapment neuritis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1990;29:119–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina R. Os peroneum fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;227:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DA, Stinson W. Excision of the fractured os peroneum: a report of five patients and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int. 1992;13:277–281. doi: 10.1177/107110079201300509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzner W. Die Sesambeine des menschlichen Körpers. Morphol Arbeiten. 1892;1:517–762. [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzner W. Die Variationen im Aufbau des Fussskelets. Morphol Arbeiten. 1896;6:245–527. [Google Scholar]

- Picou R. Insertions inférieures du long peronier lateral. Bull Assoc Anat (Nancy) 1894a;8:254–259. [Google Scholar]

- Picou R. Insertions inférieures du muscle long péronier lateral. Anomalie de ce muscle. Bull Assoc Anat (Nancy) 1894b;8:160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson JL, Inglis AE. Stenosing tenosinovitis of the peroneus longus tendon associated with hypertrophy of the peroneal tubercle and the os peroneum. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:440–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker J, Rosenberg ZS, Delfaut EM, et al. Tear of the peroneus longus tendon: MR imaging features in nine patients. Radiology. 2000;214:700–704. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.3.r00mr35700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requejo SM, Kulig K, Thordarson DB. Management of foot pain associated with accessory bones of the foot: two clinical case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:580–591. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.10.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick D, Niwayama G, Feingold ML. The sesamoid bones of the hand and feet: participators in arthitis. Radiology. 1977;123:57–62. doi: 10.1148/123.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammarco GJ. Peroneus longus tendon tears: acute and chronic. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:245–253. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammarco VJ, Cuttica DJ, Sammarco GJ. Lasso stitch with peroneal retinaculoplasty for repair of fractured os peroneum: a report of two cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:1012–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0822-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siecke H. Beitrag zur Genese des Os peroneum (Beobachtungen an 250 röntgenologisch festgestellten Ossa peronea) Z Orthop Grenzgebiete. 1964;98:358–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Johnson AH, Heckman JD. Nonoperative treatment of an os peroneum fracture in a high-level athlete: a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1498–1501. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1812-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M, Pavlov H, Geppert MJ, et al. Painful os peroneum syndrome: a spectrum of conditions responsible for plantar lateral foot pain. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:112–124. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofka CM, Adler RS, Saboeiro GR, et al. Sonographic evaluation and sonographic-guided therapeutic options of lateral ankle pain: peroneal tendon pathology associated with the presence of an os peroneum. HSS J. 2010;6:177–181. doi: 10.1007/s11420-010-9154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starck D. Embryology. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Stieda L. Der M. peroneus longus und die Fussknochen. Anat Anz. 1889a;4:600–607. [Google Scholar]

- Stieda L. Der M. peroneus longus und die Fussknochen. Anat Anz. 1889b;4:624–640. [Google Scholar]

- Stieda L. Der M. peroneus longus und die Fussknochen. Anat Anz. 1889c;4:652–661. [Google Scholar]

- Stropeni L. Frattura isolata di un osso soprannumerario del tarso (os peroneum externum) Arch Ital Chir. 1920;2:556–564. [Google Scholar]

- Tehranzadeh J, Stoll DA, Gabriele OM. Posterior migration of the os peroneum of the left foot, indicating a tear of the peroneal tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 1984;12:44–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00373176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FM, Patterson AH. Rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A:293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FM, Patterson AH. Rupture of the peroneus longus tendon. Report of three cases (letter) J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:306–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong DT, Dussault RG, Kaplan PA. Fracture of the os peroneum and rupture of the peroneus longus tendon as a complication of diabetic neuropathy. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24:626–628. doi: 10.1007/BF00204867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancauwenberghe T, Vanhoenacker FM, Van Den Abbeele K. Painful os peroneum syndrome. JBR-BTR. 2009;92:232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wander DS, Galli K, Ludden JW, et al. Surgical management of a ruptured peroneus longus tendon with a fractured multipartite os peroneum. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1994;33:124–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XT, Rosenberg ZS, Mechlin MB, et al. Normal variants and diseases of the peroneal tendons and superior peroneal retinaculum: MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2005;25:587–602. doi: 10.1148/rg.253045123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildenauer E, Muller W. Die Sehne des M. fibularis longus im Bereich des Os cuboides und ihre Beziehungen zu den kurzen Fussmuskeln. Z Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1951;115:443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RC, Moyles BG. Surgical treatment of the symptomatic os peroneum. J Foot Surg. 1987;26:156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgonis T, Jolly GP, Polyzois V, et al. Peroneal tendon pathology. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2005;22:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]