Abstract

BACKGROUND

Imatinib 400 mg daily is the standard treatment for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). The safety and efficacy of imatinib in CML patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction has not been analyzed.

METHODS

The authors analyzed the outcome of 259 patients with early chronic phase CML treated with imatinib (starting dose 400 mg in 50, 800 mg in 209). Pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction was seen in 38 (15%) and 11 (4%) patients, respectively.

RESULTS

Dose reductions were required in 91 (43%) of 210 patients with normal organ function, compared with 8 (73%) of 11 (P =.065) with renal dysfunction, and 19 (50%) of 38 (P =.271) with liver dysfunction. Grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities including anemia (29%, 10%, and 7% of patients with renal dysfunction, liver dysfunction, and normal organ function, respectively), neutropenia (57%, 30%, and 30%), and thrombocytopenia (43%, 30%, and 26%) were more frequent in patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction treated with high-dose imatinib. Grade 3-4 nonhematologic toxicities were observed at similar frequencies. Complete cytogenetic response rates, event-free survival, and overall survival were similar in all groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Although patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction might have a higher rate of hematologic toxicity and require more frequent dose reductions, most patients can be adequately managed, resulting in response rates and survival similar to those without pre-existing organ dysfunction.

Keywords: imatinib, chronic myelogenous leukemia, liver and/or renal dysfunction, dose reduction, survival

Imatinib (STI571, Gleevec) is an orally administered protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor of Bcr-Abl, c-kit, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and several other kinases .1-3 It is the first small molecule inhibitor of tyrosine kinases to be licensed for cancer treatment. Imatinib has become the standard treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)4 and metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor.5 The standard starting daily dose of imatinib is 400 mg, and higher doses have been investigated in an effort to improve the response rate.1 In newly diagnosed patients in early chronic phase CML, imatinib is associated with a complete cytogenetic response rate of 82%, a progression rate to accelerated or blastic phase of only 7%, a 7-year estimated event-free survival (EFS) rate of 81%, and overall survival (OS) of 86%.6 Imatinib is well absorbed orally, with nearly 100% bioavailability, and it is mainly metabolized in the liver via the CYP3A4/5 pathway. The main metabolite, CGP74588, is known to be active, and the elimination of this and other metabolites is >90% through the bile.7,8

Although imatinib is generally well tolerated, various hematologic and nonhematologic adverse events may occur. Hematologic adverse events (neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia) occur most frequently during the first few months of treatment and are usually transient. The most commonly observed nonhematologic adverse events include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, fluid retention, skin rash, and fatigue.9-11 Other less common adverse events, such as liver and kidney toxicity, have also been reported in the literature.3,12,13 Most of these adverse events are grade 1-2, and they are usually transient and manageable. Permanent discontinuation of imatinib for drug-related adverse events was reported in <4% of patients after a median follow-up of 60 months.9,10

Although safety and pharmacokinetic data of imatinib are available for healthy volunteers and cancer patients with normal liver and/or renal functions,7,8 the safety and efficacy of imatinib in CML patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction have not been reported, frequently prompting the use of lower starting doses in these patients. We thus performed this analysis to determine the safety and efficacy of imatinib among CML patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 259 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed Ph-positive CML in early chronic phase (time from diagnosis to therapy <12 months) were included in 3 consecutive studies. These represent all previously untreated patients referred to our institution during the study period. Chronic phase was defined per standard criteria for tyrosine kinase inhibitor trials as: blasts <15%, basophils <20%, blasts + promyelocytes <30%, no extramedullary disease, platelets >100 × 109/L (unless related to therapy), and no clonal evolution.14,15 Patients were required to be at least 15 years old and to have adequate performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0-2) and normal cardiac function. Women of childbearing age were required to have a negative pregnancy test before starting imatinib, and all patients at risk were required to use contraception during therapy. Patients provided written informed consent before entry into the study, which was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Classification of Renal and Liver Function

Renal and liver functions were classified according to previous publications.16,17 Renal function was based on the calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl).18 Normal renal function was defined as CrCl 60 mL/min or higher; mild dysfunction as CrCl 40-59 mL/min; moderate dysfunction as CrCl 20-39 mL/min; and severe dysfunction as CrCl less than 20 mL/min. Liver function was classified according to the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and serum total bilirubin (TB) levels measured within 24 hours before the start of imatinib. Normal was defined as TB ≤ upper limit of normal (ULN) and AST ≤ ULN; mild as TB ≤ 1.5 × ULN and AST>ULN; moderate as TB 1.5 to 3.0 × ULN and AST of any value; and severe as TB >3 × ULN and AST of any value. Dysfunction was considered regardless of causality, as no pretreatment biopsies were performed to investigate the possibility of disease infiltration as a contributor.

Treatment and Dose Modifications

Imatinib was given at a starting dose of 400 mg daily (n = 50) or 400 mg twice daily (n = 209). Dose reductions of imatinib for hematologic and nonhematologic toxicities were as follows: for persistent grade 2 nonhematologic drug-related toxic effects, therapy was interrupted until recovery to grade 1 or less and resumed at the original dose level. If grade 2 toxicity recurred, treatment was interrupted again until recovery and resumed at −1 dose level. For grade 3 and 4 nonhematologic toxicities, therapy was interrupted until recovery to grade 1 or less and then resumed at −1 dose level. For severe hematologic toxicity (neutrophil count of <0.5 × 109/L or platelet count of <40 × 109/L), therapy was interrupted until neutrophils recovered to 109/L or higher and/or platelets to 60 × 109/L or higher. If the toxicity resolved within 2 weeks, treatment was resumed at the original dosage. If toxicity resolved after >2 weeks, or if it recurred after resuming therapy, treatment was restarted with a −1 dose level reduction. Further dose reductions were allowed using the same guidelines for recurrent hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity, with the lowest dose allowed being 300 mg daily.

Monitoring and Assessment of Response

Complete blood counts and serum chemistry were done weekly during the first 4 weeks of treatment, then every 6 to 8 weeks thereafter. Bone marrow studies, including morphologic, cytogenetic, or fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis, were performed every 3 months in the first year, then every 3 to 6 months thereafter. Patients were followed for survival at least every 3 months. Drug safety was evaluated at each visit and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (version 3.0).

Hematologic and cytogenetic response criteria have been previously described.9,19 Briefly, a complete cytogenetic response rate represents Ph positivity 0%, partial cytogenetic response represents Ph positivity 1% to 35%, and minor cytogenetic response represents Ph positivity 36%-95%. A major cytogenetic response includes both complete cytogenetic response and partial cytogenetic response. Cytogenetic responses were based on the percentage of Ph+ metaphases in ≥20 metaphases.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif), and Statistica 6 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, Okla). The Fisher exact test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare significance between groups. All reported P values were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Survival was dated from the start of imatinib therapy until death from any cause and censored at last follow-up for patients who were alive. EFS was calculated from the start of imatinib to loss of complete hematologic response, loss of major cytogenetic response, transformation to accelerated or blast phase, or death from any cause. Patients who discontinued for other reasons (eg, noncompliance, financial issues, lost to follow-up) were censored at date of last treatment and patients still on treatment at date of last follow-up.

RESULTS

Study Patients

A total of 259 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase CML were treated with imatinib from March 2001 to July 2005. The clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics between patients treated with imatinib 400 mg and 800 mg. Eleven patients had renal dys-function at the start of treatment, which was mild in 9 (82%) and moderate in 2 (18%) patients (Table 1). Of the 50 patients treated with imatinib 400 mg daily, 4 (8%) had mild renal dysfunction, whereas in the 800 mg daily group, 5 (3%) had mild and 2 (1%) moderate renal dysfunction. Liver dysfunction was present at baseline in 38 patients, all of them mild. These included 7 (14%) of the 50 patients treated with standard-dose imatinib and 31 (16%) of the 209 treated with high-dose imatinib. Per study eligibility criteria, patients with more severe liver dysfunction were excluded from the studies. Only 1 patient had both renal (moderate) and liver (mild) dys-function at the start of imatinib treatment. In the 11 patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction, 2 (18%) had low, 8 (73%) had intermediate, and 1 (9%) had high Sokal risk disease. In the 38 patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction, 24 (63%) had low, 11 (29%) had intermediate, and 3 (8%) had high Sokal risk disease.20,21

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population

| Parameter | Imatinib 400 mg [n=50] | Imatinib 800 mg [n=209] |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 47 (15-79) | 51 (17-84) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 26 (52) | 83 (40) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L), median (range) | 12.5 (7.9-15) | 12.2 (6.2-16.7) |

| Neutrophil (×109/L), median (range) | 15.5 (0.5-158) | 19.2 (0-164) |

| Platelet (×109/L), median (range) | 433 (139-1043) | 420 (58-1476) |

| Splenomegaly, No. (%) | 11 (22) | 60 (29) |

| Median follow-up, mo (range) | 84 (2-90) | 59 (4-85) |

| Sokal risk score, No. (%) | ||

| Low | 33 (66) | 132 (63) |

| Intermediate | 15 (30) | 58 (28) |

| High | 2 (4) | 19(9) |

| Renal function, No. (%) | ||

| Normal | 46 (92) | 202 (97) |

| Mild | 4 (8) | 5 (3) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Liver function, No. (%) | ||

| Normal | 43 (86) | 178 (84) |

| Mild | 7 (14) | 31 (16) |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Severe | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Changes in Kidney and Liver Function After Imatinib Treatment

Among 50 patients treated with standard dose imatinib, 9 (18%) experienced worsening renal function while on treatment. All 4 patients with mild renal dysfunction at the start of treatment developed further worsening in renal function, as shown by a decrease in CrCl from a median baseline of 51.5 mL/min (range, 45.4-59.9 mL/ min) to a median of 41.8 mL/min (range, 32.8-47 mL/ min). Three of them maintained a mild dysfunction, and 1 progressed to moderate dysfunction. One patient with normal renal function (creatinine 0.7 mg/dL and CrCl 93.86 mL/min) experienced severe renal failure (creati-nine 8.6 mg/dL and CrCl 8.99 mL/min). Imatinib was temporarily discontinued in this patient and restarted at a lower dose once the renal function recovered. Among patients on high-dose imatinib, 33 (16%) developed transient worsening of renal function. All 7 patients with preexisting renal dysfunction developed further decrease in their CrCl from a median baseline of 44.4 mL/min (range, 28.5-57.8 mL/min) to a median of 36.9 mL/min (range, 13.5-55.8 mL/min). While being treated with imatinib, 2 of the patients with pre-existing moderate renal dysfunction (CrCl 28.45 and 34.49 mL/min) progressed to severe renal dysfunction (CrCl 15.62 and 13.53 mL/min), 1 patient with mild dysfunction progressed to moderate dysfunction, and 4 maintained a mild dysfunction. The worsening of renal function was usually transient; temporary discontinuation of imatinib resulted in recovery of the renal function. All but 1 patient were able to restart the imatinib at a lower dose without further decline of their renal function.

Fifteen (30%) patients developed liver toxicity during the treatment with standard-dose imatinib, including 8 (53%) with mild, 5 (33%) with moderate, and 2 (14%) with severe liver dysfunction. Only 1 of the 7 patients with pre-existing mild liver dysfunction progressed to moderate liver dysfunction, 3 maintained a mild dysfunction, and the liver function of the 3 other patients normalized. In the high-dose group, 36 (17%) patients developed liver toxicity, including 26 (72%) with mild, 7 (19%) with moderate, and 3 (9%) with severe dysfunction. Only 3 of the 31 patients with mild liver dysfunction at the baseline experienced worsening of their liver function, 2 to moderate and 1 to severe liver dysfunction. Seventeen of the 31 patients still have persistent mild dysfunction, whereas the liver function of 11 patients returned to normal.

Toxicity Profile and Dose Modification

We then analyzed the overall toxicity profile in patients with or without pre-existing organ dysfunction treated with standard-dose (Table 2) and high-dose imatinib (Table 3). With the limitations of the small number of patients in some subsets, patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction treated with high-dose imatinib appeared to have a higher rate of grade 3-4 hematologic toxicities. These include anemia (29%, 10%, and 7% in patients with renal dysfunction, liver dysfunction, and normal organ function, respectively [P = .11]), neutropenia (57%, 30%, and 30% [P = .31]), and thrombocytopenia (43%, 30%, and 26% [P = .57]). The frequencies of other adverse events were rare and did not appear to be significantly affected by pre-existing organ dysfunction or imatinib dose.

Table 2.

Toxicity Profiles in Patients Treated With Imatinib at 400 mg Daily

| Toxicity | No. (%) by Organ Function | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal (n=4) | Liver (n=7) | Normal (n=39) | ||||

| All | G3-4 | All | G3-4 | All | G3-4 | |

| Anemia | 4 (100) | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 | 34 (87) | 1 (3) |

| Neutropenia | 3(75) | 0 | 3 (43) | 1 (14) | 19 (49) | 7 (18) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3(75) | 0 | 5 (71) | 2 (28) | 18 (46) | 4 (10) |

| Rash | 2(50) | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 10 (26) | 1 (3) |

| Edema | 2(50) | 0 | 2 (28) | 0 | 15 (38) | 1 (3) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2(50) | 1 (25) | 3 (43) | 0 | 15 (38) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 11 (28) | 0 |

| Liver toxicity | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 2 (28) | 1 (14) | 12 (31) | 3 (8) |

| Muscle cramp | 2 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (31) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (28) | 0 | 13 (33) | 0 |

| Kidney toxicity | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 7 (18) | 1 (3) |

| Pleural effusion | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

G indicates grade.

Table 3.

Toxicity Profiles in Patients Treated With Imatinib at 800 mg Daily

| Toxicity | No. (%) by Organ Function | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal (n=7) | Liver (n=31) | Normal (n=171) | ||||

| All | G3-4 | All | G3-4 | All | G3-4 | |

| Anemia | 7 (100) | 2 (29) | 29 (94) | 3 (10) | 150 (88) | 12 (7) |

| Neutropenia | 7 (100) | 4 (57) | 23 (74) | 9 (30) | 117 (68) | 52 (30) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (72) | 3 (43) | 27 (87) | 9 (30) | 127 (74) | 44 (26) |

| Rash | 3 (43) | 1 (14) | 9 (29) | 3 (10) | 63 (37) | 13 (8) |

| Edema | 4 (57) | 1 (14) | 20 (65) | 0 | 94 (55) | 3 (2) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (29) | 0 | 10 (32) | 0 | 44 (26) | 3 (2) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (43) | 0 | 14 (45) | 1 (3) | 51 (30) | 7 (4) |

| Liver toxicity | 3 (43) | 0 | 14 (45) | 2 (6) | 21 (12) | 5 (3) |

| Muscle cramp | 2 (29) | 0 | 12 (39) | 0 | 74 (43) | 3 (2) |

| Fatigue | 1 (14) | 0 | 5 (16) | 0 | 51 (30) | 4 (2) |

| Kidney toxicity | 2 (29) | 0 | 3 (10) | 0 | 21 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

G indicates grade.

Transient treatment interruptions and dose reductions were required in patients receiving imatinib therapy for hematologic or nonhematologic side effects (Table 4). Dose reductions were necessary in 91 (43%) of 210 patients with normal organ function at the start of imatinib treatment, including 6 (15%) of 39 in the 400-mg group and 85 (50%) of 171 in the 800-mg group. This compares to 8 (73%) of 11 (P = .07) patients (2 [50%] of 4 in the 400-mg group and 6 [86%] of 7 in the 800-mg group) with pre-existing renal dysfunction, and 19 (50%) of 38 (P = .27) patients (2 [29%] of 7 in the 400-mg group and 17 [55%] of 31 in the 800-mg group) with pre-existing liver dysfunction.

Table 4.

Dose Reduction by Pre-Existing Organ Function and Imatinib Dose

| Imatinib | Organ Function | Dose Reduction, No. (%) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 400 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=4) | 2 (50) | .14 |

| Liver dysfunction (n=7) | 2 (29) | .20 | |

| Normal (n=39) | 6 (15) | ||

| 800 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=7) | 6 (86) | .12 |

| Liver dysfunction (n=31) | 17 (55) | .56 | |

| Normal (n=171) | 85 (50) |

P value is compared with patients with normal organ function.

In patients treated with imatinib 400 mg daily, 22 of the 26 (85%) evaluable patients with normal organ function were still on 400 mg at 48 months follow-up. This compared with 1 (50%) of the 2 evaluable patient with pre-existing renal dysfunction and all (100%) of the 4 evaluable patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction (Table 5). In patients treated with high-dose imatinib, 66 (54%) of the 122 evaluable patients with normal organ function were still on 800 mg, 33 (27%) were reduced to 600 mg, 20 (16%) were reduced to 400 mg, and 3 (3%) were reduced to 300 mg at 48 months follow-up. In patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction, 1 (17%) of the 6 evaluable patients remained at 800 mg, 2 (33%) were reduced to 600 mg, 2 (33%) were reduced to 400 mg, and 1 (17%) was reduced to 300 mg. In patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction, 14 (66%) of the 21 evaluable patients remained at 800 mg, 5 (24%) were reduced to 600 mg, and 2 (10%) were reduced to 400 mg. At 48-months follow-up, 3 (27%) patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction, 13 (34%) with pre-existing liver dysfunction, and 62 (29%) with normal organ function were taken off-study for various reasons. The most common reasons for being off-study were administrative issues (n = 30), loss of response or disease progression (n = 23), and liver toxicity (n = 9).

Table 5.

Imatinib Dose at 48 Months Follow-up by Pre-Existing Organ Function

| Imatinib | Evaluable Patient | Imatinib Dose at 48 Months, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 mg | 400 mg | 600 mg | 800 mg | ||

| 400 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=2) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) |

| Liver dysfunction (n=4) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal (n=26) | 3 (11) | 22 (85) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| 800 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=6) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 1 (17) |

| Liver dysfunction (n=21) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 5 (24) | 14 (66) | |

| Normal (n=122) | 3 (3) | 20 (16) | 33 (27) | 66 (54) | |

The most common reasons for dose reduction in patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction were myelo-suppression (n = 3), rash (n = 2), liver toxicity (n = 1), and renal toxicity (n = 1). In the patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction, the most common reasons for dose reduction included myelosuppression (n = 5), rash (n = 4), gastrointestinal toxicity (n = 4), and liver toxicity (n = 3).

Responses and Survival

Despite the trend for more treatment interruptions and dose reductions among patients with pre-existing organ dysfunctions, the response rate did not differ between patients with and without organ dysfunction (Table 6). In patients treated with standard-dose imatinib, the complete cytogenetic response rates were 75% (3 of 4), 71% (5 of 7), and 82% (32 of 39) in patients with renal dys-function, liver dysfunction, and normal function, respectively (P = .27). In patients treated with high-dose imatinib, the complete cytogenetic response rate rates were 86% (6 of 7), 97% (30 of 31), and 88% (151 of 171), respectively (P = .15).

Table 6.

Response to Imatinib by Pre-Existing Organ Functions

| Imatinib | Organ Function | Response, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCyR | PCyR | mCyR | CHR, No CCyR | Resistant | Unevaluable | ||

| 400 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=4) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Liver dysfunction (n=7) | 5 (71) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal (n=39) | 32 (82) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| 800 mg | Renal dysfunction (n=7) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Liver dysfunction (n=31) | 30 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal (n=171) | 151 (88) | 6 (4) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | |

CCyR indicates complete cytogenetic response; PCyR, partial cytogenetic response; mCyR, minor cytogenetic response; CHR, complete hematologic response.

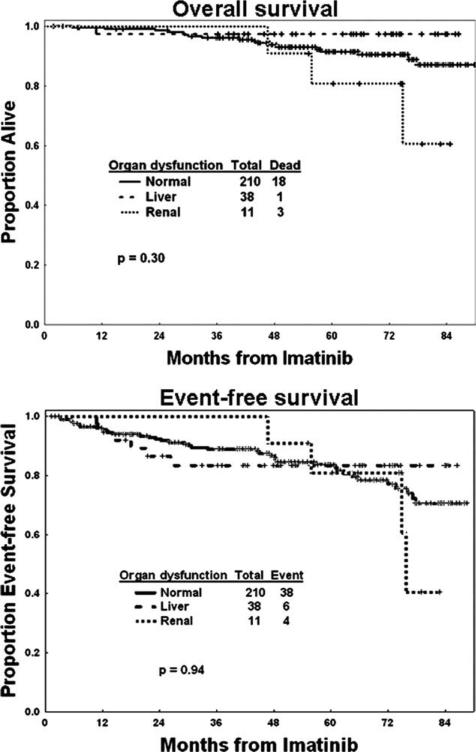

With a median follow-up of 63 months (range, 2-90 months), 22 patients have died, including 3 (27%) of 11 patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction, 1 (3%) of 38 patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction, and 18 (9%) of 210 patients with normal organ function. The causes of death for the 4 patients with baseline organ dys-function were disease progression, ovarian cancer, cardiac event, and unknown cause, respectively. The estimated 5-year OS was 80% for those with renal dysfunction, 97% for those with liver dysfunction, and 91% for those with normal organ function (P = 0.3) (Fig. 1). EFS was also similar within the 3 groups of patients, with 5-year estimates of 80%, 82%, and 82%, respectively (P = .94). The Sokal risk score did not correlate with either OS (P = .96) or EFS (P = .18). There was no difference in the OS and EFS among the 3 groups of patients, regardless of the imatinib starting dose.

Figure 1.

Overall survival and event-free survival are shown in patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction, renal dysfunction, and normal organ function treated with front-line imatinib.

DISCUSSION

Although it is well known that imatinib is overall well tolerated, currently available data only refer to patients with normal organ functions. However, occasionally patients with CML present with pre-existing conditions that cause renal or liver dysfunctions. The safety and efficacy of imatinib in such patients has not been previously reported. These patients may sometimes be offered other therapies or a lower starting dose because of the lack of published information. Recently, 2 phase 1 and pharmacokinetic studies of imatinib were performed by the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group in patients with advanced malignancies who presented with liver or renal dysfunctions.16,17 They found that serious adverse events were more common in the group with renal dysfunction, but there was no correlation between dose and serious adverse events in any group. In these studies, daily imatinib doses up to 800 mg were well tolerated by many patients with mild and moderate renal dysfunction despite increased imatinib exposure. Imatinib exposure did not differ between patients with and without liver dys-function. The maximal recommended dose of imatinib for patients with mild liver dysfunction was 500 mg daily, whereas dosing guidelines for patients with moderate and severe liver dysfunction remained undetermined based on these studies.16,17

To further investigate the safety and effectiveness of imatinib in CML patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction, we analyzed the outcome of 259 patients with early chronic phase CML treated at our institution with imatinib either at standard (400 mg daily) or high dose (800 mg daily). Among the 259 patients included in the analysis, 4% had pre-existing mild or moderate renal dysfunction, and 14% had mild liver dysfunction.

According to our results, imatinib is similarly effective among patients with or without pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction; this is also reflected in a similar OS and EFS. The toxicity profile also appears similar for patients with or without organ dysfunctions, with the possible exception of myelosuppression, which appears to be more frequent among patients with pre-existing renal dys-function treated with high-dose imatinib. The incidence of most nonhematologic toxicities did not appear significantly different regardless of the dose, with the limitations of small subsets for this analysis. These results are in agreement with the reports from Gibbons et al.16 and Ramana-than et al.17 showing overall good tolerance to treatment of solid tumors among patients with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction.

Of particular interest is assessment of whether the liver and/or renal functions further deteriorate during therapy, because imatinib has been reported to cause both renal and liver toxicity.10,22 Renal dysfunction indeed deteriorated in all 11 patients who started therapy with mild or moderate renal dysfunction. This is in contrast to patients who started therapy with normal renal function, of whom only 12% (31 of 248) developed renal dysfunction. Deterioration of renal function among patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction was fortunately transient and could be managed with dose adjustments, with no patients requiring dialysis. Worsening of liver function was less common, with only 3 of the 38 patients with pre-existing liver dysfunction experiencing deterioration of their liver function during treatment.

The lack of impact of Sokal risk score on the long-term outcome is indeed interesting, but the cause for this is not clear from this analysis. It has been previously reported from the International Randomized Study of Interferon Versus STI571 trial that patients who achieved a complete cytogenetic response have a similar long-term outcome regardless of their pretreatment Sokal score.11 It is possible that the use of high-dose imatinib may have improved the response rate among this patient population to dilute the effect of the Sokal score. Exploring the reason for this phenomenon is an important research question, but we believe it is beyond the scope of this analysis.

It is important to emphasize the retrospective nature of this analysis, which could affect some of the conclusions. However, even when the analysis is retrospective, patients were treated in prospective studies, and data collection was in real time. It should also be emphasized that because these patients were treated in clinical trials, there was very close follow-up of all patients, with frequent monitoring of efficacy and safety.

We conclude that imatinib is an effective therapy for patients with CML who present with pre-existing liver and/or renal dysfunction. There might be an increased risk for worsening renal function among patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction, and a higher risk of other toxicities, particularly myelosuppression for patients treated with higher doses. Nonetheless, most patients with mild or moderate liver dysfunction, and to some extent those with renal dysfunction, can be safely offered therapy with standard-dose imatinib.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by research funding from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Jorge Cortes and Hagop Kantarjian receive research support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. High-dose imatinib mesylate therapy in newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:2873–2878. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Imatinib mesy-late for Philadelphia chromosome-positive, chronic-phase myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-alpha: follow-up results. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2177–2187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Cortes J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Goldman JM, et al. International Randomized Study of Interferon Versus STI571 (IRIS) 7-Year follow-up: sustained survival, low rate of transformation and increased rate of major molecular response (MMR) in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CMLCP) treated with imatinib (IM) [abstract]. Blood. 2008:112. Abstract 186. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng B, Dutreix C, Mehring G, et al. Absolute bioavailability of imatinib (Glivec) orally versus intravenous infusion. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:158–162. doi: 10.1177/0091270003262101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng B, Hayes M, Resta D, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imatinib in a phase I trial with chronic myeloid leukemia patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:935–942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochhaus A, Druker B, Sawyers C, et al. Favorable long-term follow-up results over 6 years for response, survival, and safety with imatinib mesylate therapy in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-alpha treatment. Blood. 2008;111:1039–1043. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy L, Guilhot J, Krahnke T, et al. Survival advantage from imatinib compared with the combination interferon-alpha plus cytarabine in chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: historical comparison between 2 phase 3 trials. Blood. 2006;108:1478–1484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hensley ML, Ford JM. Imatinib treatment: specific issues related to safety, fertility, and pregnancy. Semin Hematol. 2003;40:21–25. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foringer JR, Verani RR, Tjia VM, et al. Acute renal failure secondary to imatinib mesylate treatment in prostate cancer. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:2136–2138. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochhaus A, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al. Follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Levy V, et al. Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to imatinib at a dose of 400 to 600 milligrams daily: 2-year follow-up of a randomized phase 2 study (START-R). Cancer. 2009;115:4136–4147. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons J, Egorin MJ, Ramanathan RK, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of imatinib mesylate in patients with advanced malignancies and varying degrees of renal dysfunction: a study by the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:570–576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanathan RK, Egorin MJ, Takimoto CH, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of imatinib mesylate in patients with advanced malignancies and varying degrees of liver dysfunction: a study by the National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:563–569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantarjian H, Sawyers C, Hochhaus A, et al. Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:645–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokal JE, Cox EB, Baccarani M, et al. Prognostic discrimination in “good-risk” chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1984;63:789–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kantarjian HM, Keating MJ, Smith TL, et al. Proposal for a simple synthesis prognostic staging system in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Med. 1990;88:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong JH, Yoo SH, Lee KE, et al. Early imatinib-mesylate-induced hepatotoxicity in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Acta Haematol. 2007;118:205–208. doi: 10.1159/000111092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]