Abstract

Aim:

This systematic literature review was conducted to identify, evaluate, and characterize the variety, quality, and intent of the health economics and outcomes research studies being conducted in India.

Materials and Methods:

Studies published in English language between 1999 and 2012 were retrieved from Embase and PubMed databases using relevant search strategies. Two researchers independently reviewed the studies as per Cochrane methodology; information on the type of research and the outcomes were extracted. Quality of reporting was assessed for model-based health economic studies using a published 100-point Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) instrument.

Results:

Of 546 studies screened, 132 were included in the review. The broad study categories were cost-effectiveness analyses [(CEA) 54 studies], cost analyses (19 studies), and burden of illness [(BOI) 18 studies]. The outcomes evaluated were direct and indirect costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Direct medical costs assessed cost of medicines, monitoring costs, consultation and hospital charges, along with direct non-medical costs (travel and food for patients and care givers). Loss of productivity and loss of income of patients and care givers were identified as the components of indirect cost. Overall, 33 studies assessed the quality of life (QoL), and the WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) was the most commonly used instrument. Quality assessment for modeling studies showed that most studies were of high quality [mean (range) QHES score to be 75.5 (34-93)].

Conclusions:

This review identified various patterns of pharmacoeconomic studies and good-quality CEA studies. However, there is a need for better assessment of utilization of healthcare resources in India.

Keywords: Cost analysis, health economics, India, outcomes research, pharmacoeconomic

INTRODUCTION

Health economics is a branch of economics that assesses the issues related to efficiency, effectiveness, and value of resources in health and healthcare. Such evaluations are important in understanding the economic aspects of health and disease and the limitations to procurement of adequate healthcare. This aids in decision making, not only for policy makers and health administrators but also in clinics, for providers and care givers.[1,2]

Health economic evaluations are more evolved in societies having reimbursement systems. India still lags behind in terms of healthcare financing and implementation of policies.[3] The health scenario in India is mired by increasing industrialization coupled with changes in lifestyle and continued lack of disease awareness among the masses. The urban population is at a higher risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS).[4] In the rural parts of the country, infectious and waterborne diseases and reproductive tract infections continue to predominate, though the risk of developing chronic diseases is also increasing.[5] It is, therefore, a challenge for healthcare providers to promote health using improved and cost-effective modalities for the prevention, diagnosis, and therapy of various diseases and aliments.

The disparity in health services provision across the country, along with burgeoning healthcare expenditure underlines the need for effective utilization of healthcare resources. The rapid growth of the pharmaceutical sector too has brought forth a need for clinical as well as economic evidence generation for drugs, medical devices, procedures, and diagnostics to enable an objective evaluation of their value to various stakeholders faced with multiple choices. Presently, there are small numbers of studies evaluating the cost of healthcare in India.

This systematic literature review was conducted with the objective to identify, evaluate, and characterize the variety, quality, and intent of the health economics and outcomes research studies being conducted in India. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most recent and comprehensive review of such studies and was planned to fill the evidence gap in published literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

The Embase and Medline (through PubMed) databases were searched for English language studies published between 1999 and 2012. The search criteria used a combination of terms such as “health economics,” “healthcare cost,” “economic burden,” “costs and cost analysis,” “drug cost,” “cost benefit analysis,” “cost of illness,” “cost-effectiveness analysis,” “quality of life,” “patient reported outcomes,” and “India.”

Selection criteria

Studies were included if they assessed health economics, cost analysis (CA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost benefit analysis (CBA), cost of illness (COI), burden of illness (BOI), quality of life (QoL), and patient reported outcomes. All included studies were conducted in India only. All prospective and retrospective studies were included except for case studies and case reports. References from systematic review and meta-analyses were screened for potential relevant studies.

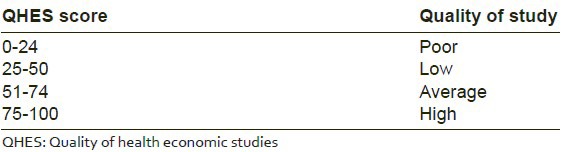

Data collection and analysis

Following the decision on inclusion/exclusion of studies, a two-stage data extraction process was used to capture the necessary information, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer. The main outcomes were type of pharmacoeconomic evaluation, disease type, cost outcomes, and QoL. Quality of reporting in model-based health economic studies was assessed using a published 100-point Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) instrument;[6] the criteria for categorizing the quality are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for quality of health economic studies using instrument

RESULTS

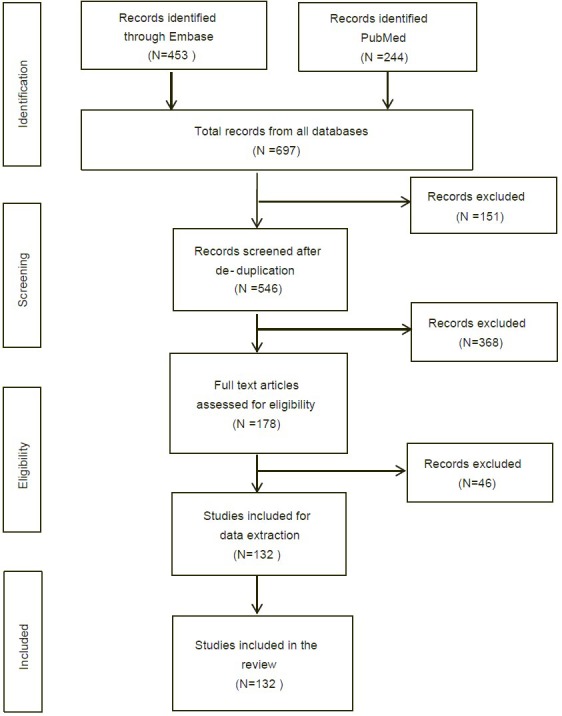

In total, 546 studies were identified for screening from all databases and 132 studies were included in the review. The flow of studies as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) is presented in Figure 1. Overall, 75% of studies were published in or after 2007. In general, studies were conducted as prospective or retrospective observational studies or as survey. A few prospective randomized studies also evaluated costs. Most of the studies were conducted from societal perspective, including both provider and patient costs. The included studies represented different disease areas such as infectious and tropical diseases (28 studies), chronic diseases (19 studies), cancer (6 studies), HIV/AIDS (6 studies), mental health and psychiatric illness (6 studies), maternal and child health (3 studies). and miscellaneous (64 studies). There were 19 studies assessing various outcomes in pediatric patients.

Figure 1.

Flow of studies as per PRISMA flow diagram

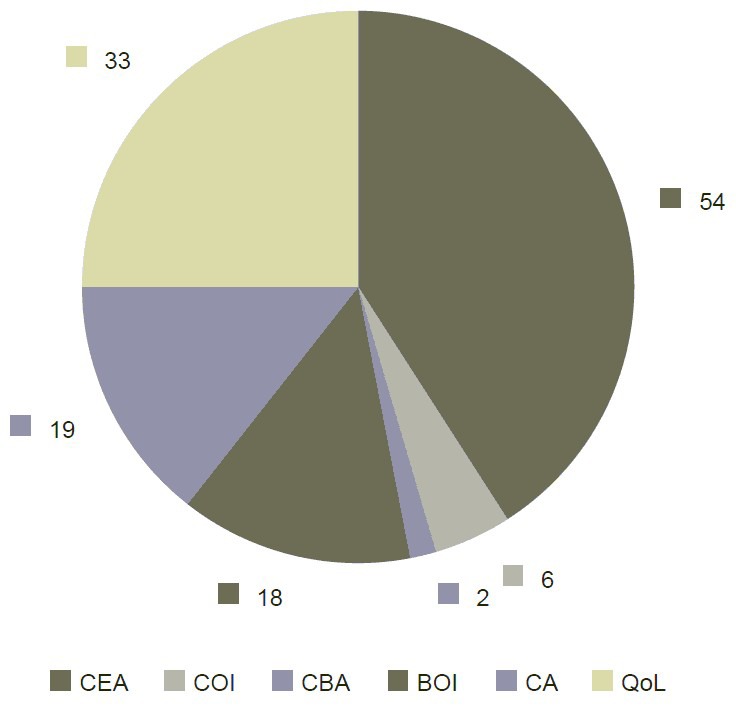

All the included studies assessed costs due to disease, and were broadly categorized into CEA (54 studies), CA (19 studies), and BOI (18 studies). The graphical depiction of all included studies is given in Figure 2. Only 35 studies adopted modeling approaches to estimate costs. Economic evaluation and QoL assessments were commonly estimated in patients with HIV/AIDS, carcinomas, or tuberculosis (TB). Studies also evaluated CEA of vaccines for immunization of children.

Figure 2.

Categorization of included studies. BOI = Burden of illness, CA = Cost analysis, CBA = Cost benefit analysis, CEA = Cost-effectiveness analysis, COI = Cost of illness, QoL = Quality of life

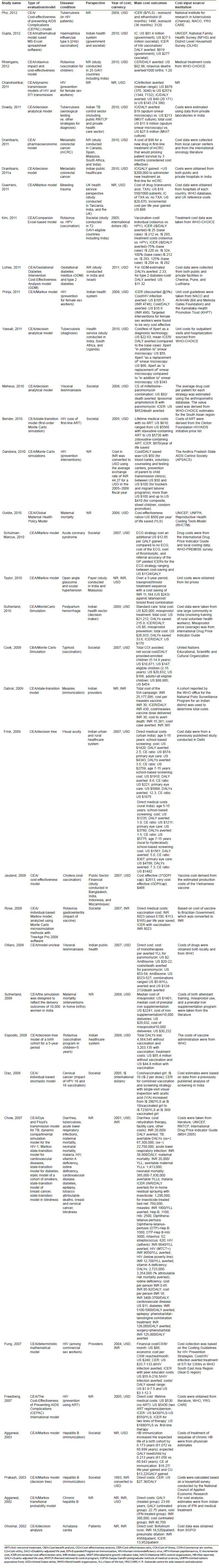

The outcomes evaluated in cost studies [Table 2] were direct and indirect costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). A study conducted CEA of universal hepatitis B (HB) immunization in India using the Markov model (with or without costs of treatment of long-term complications of HB infection) for calculation of marginal cost of every life year and QALY gained with universal HB vaccination.[7] The immunization program increased the expected life of a birth cohort by 0.173 years (61.072 vs. 60.899 years) and the expected QALY lived per child by 0.213 years (61.056 vs. 60.843 years). This resulted in highly cost-effective universal HB immunization with intermediate endemicity rates in low-income population.[7] The burden of disease can be quantified using DALY. A study estimated the burden of disease due to cancer for both genders and found that the DALY would increase from 4,598,976 in 2001 to 6,904,358 by 2016. Premature mortality was identified as a major contributor to disease burden in this study.[8]

Table 2.

Overview of cost-effectiveness studies

Economic evaluation is also involved in comparison of procedures. The CA and QoL were assessed in a prospective, randomized trial to compare mesh fixation techniques with and without tacks in patients undergoing laparoscopic repair of incisional and ventral hernia repair.[9] The two groups were equally effective for recurrence rates, complications, hospital stay, chronic pain, and patient satisfaction. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean cost per patient in the suture group ($521) as compared to the tacker group ($1097) (P < 0.001).[9]

Direct costs assessed medical costs including cost of medicines, monitoring costs, consultation and hospital charges, along with direct non-medical costs (travel and food for patients and care givers). In HIV patients, resource utilization and costs were estimated from Y. R. Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education (YRG CARE) in Chennai, India and from National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) (for HIV anti-retroviral therapies).[10] In another study for cost-effectiveness of visceral leishmaniasis, the average drug cost per patient for each strategy (treatment) was estimated using the anthropometric database.[11] Many studies conducted in India were sponsored by large institutions, and most of the studies on infectious and tropical diseases and maternal and child health were funded or supported by international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Indirect cost components included loss of productivity and loss of income of patients and care givers. However, one prospective randomized study included the cost of materials (instruments used, sterilization process, electrical costs), manpower (surgeons, anesthetists, nurses, and other staff), and hospital rents (operating room and stay in hospital until the patient is deemed fit for discharge) as indirect costs.[9] These costs were calculated by the institutional database. A few of the studies obtained indirect cost estimates by direct patient interview.

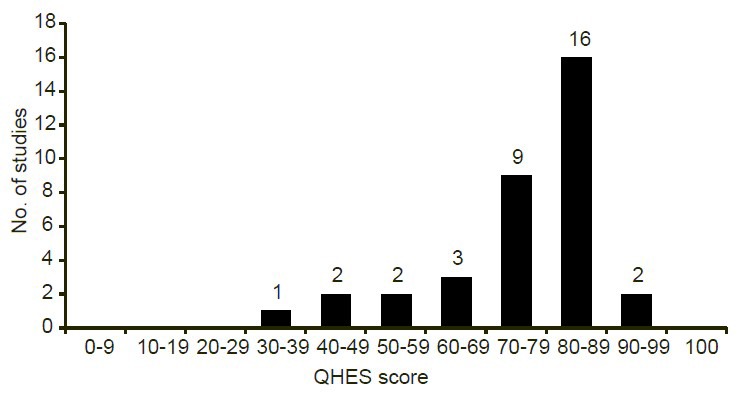

For quality assessment, the QHES instrument was used, which is a reliable instrument for assessing quality of health economic evaluations. The QHES scores were estimated for quality assessment of full economic studies (35 studies). The assessment of quality for these studies showed that most studies were of high quality [mean (range) QHES score to be 75.5 (34-93)] as presented in Figure 3. There were 24 studies out of 35 with QHES score >75. Decision tree analysis or Markov model was mostly used in these pharmacoeconomic studies. None of the studies met all the criteria of the QHES instrument.

Figure 3.

Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) total score for model-based studies (n = 35)

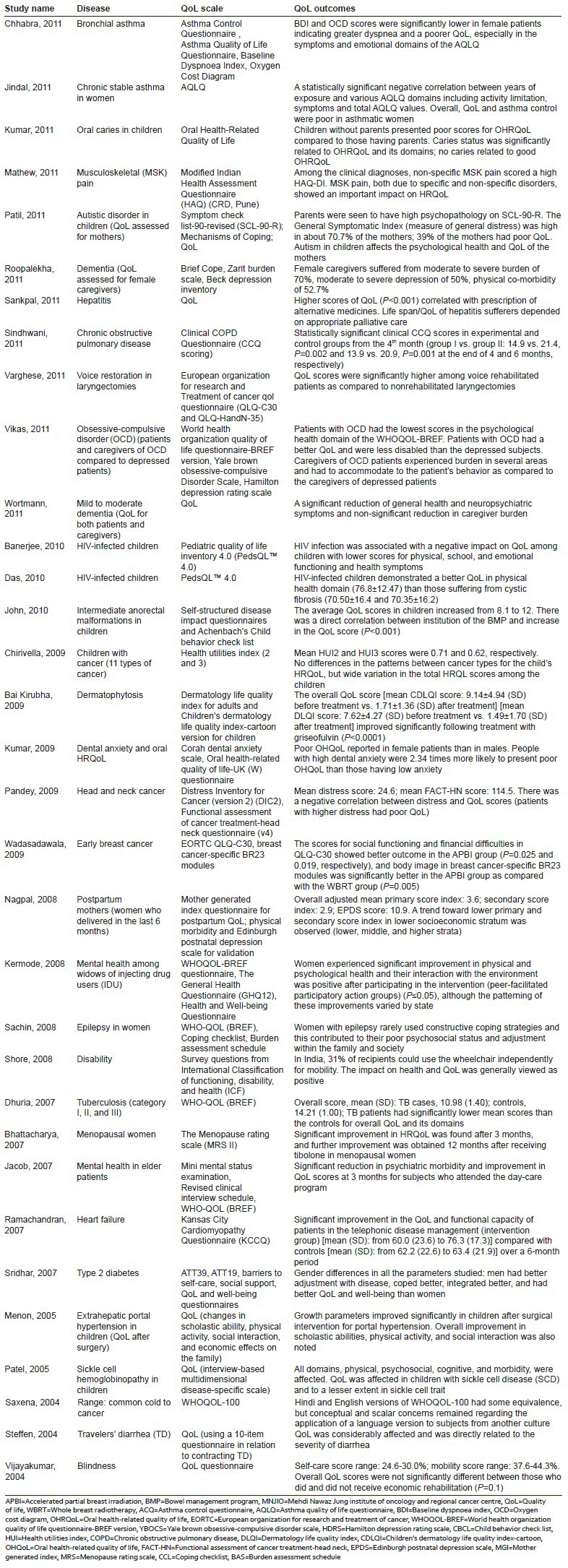

Overall, 33 studies assessed QoL, and the WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) was the most commonly used instrument in these studies [Table 3]. The WHOQOL-BREF was used in a study assessing changes in QoL in widows of injecting drug users (HIV-related deaths).[12] In HIV-infected children, health-related QoL (HRQoL) was assessed using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ (PedsQL™) in two studies.[13,14] A 40-item Health Utilities Index (HUI) was used for assessment of HRQoL in children with cancer from their physicians’ perspective.[15] There were no differences in the patterns observed between cancer types for the child's HRQoL. However, a wide variation was seen in the total HRQoL scores among the children.

Table 3.

Overview of QoL studies

DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides the current overview of health economic studies in India. Most studies that were identified could not be classified as full-fledged health economic studies. This is perhaps a reflection of the lack of understanding of standard concepts of health economics in India. A systematic review (Desai et al.) published in 2012 looked at the quality of 29 model-based studies from India.[16] Our literature review being more recent assesses the quality and tabulates the results of 35 studies along with the source of cost inputs across those studies. Most studies were sponsored by or conducted in collaboration with major institutes in India. This brings forth the fact that sponsorship and motivation are the major factors in conducting such evaluations in India. In addition, we report on the diversity of other health economics and outcomes research studies from India, including QoL or patient reported outcomes studies.

Most of the model-based studies included CEA and the perspective was societal. However, we also found studies that used modified societal perspective,[17] hospital perspective,[18] provider's perspective,[19] and patient's perspective.[20] In the study assessing costs incurred by pulmonary TB patients in rural India,[20] the financial burden for TB treatment was imposed on the patients, despite the provision of free smears and drugs by The Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) in India. The single greatest cost was time lost during admission; the total patient costs represented 193% of the estimated monthly income of a manual laborer. One of the reasons for the high expenditure was treatment at private healthcare centers. Another study estimating expenses for chemotherapy, side-effect management, and best supportive care in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer found significantly lower cost of care in public healthcare centers as compared to the private centers in India. This may be a reflection of the modest level of care offered to patients in public hospitals and the ability of the private sector to mark up the cost of goods and health services.[21]

An understanding of the true cost measures including all direct and indirect cost components is necessary while formulating national policies. CEAs are more appropriate for similar outcomes measures for interventions. When assessing dissimilar outcomes of interventions or comparing different health states, CBA and cost-utility analysis (CUA) are more useful. The cost-effectiveness of any procedure or intervention reflects the proper utilization of the available resources. As healthcare resources are scarce, it is necessary to analyze the cost of treatment modalities that have the same therapeutic potential and to identify the alternatives that are most efficient and cost-effective to derive the same benefit.[9] For example, estimation of DALY combines information on morbidity, mortality, and disability to provide an indicator of the burden of disease. Thus, the estimation of burden of cancer by DALY shows that there is a need to initiate measures for prevention and control of cancers.[8] The modern cancer medicines are often out of reach to a broader population due to their high costs. Therefore, in countries like India that have no central healthcare costs evaluation process, the WHO criteria for cost-effectiveness may be applied for estimation of appropriate and affordable prices.[21]

Another obstacle in the implementation of adequate healthcare in India is the existence of multiple health practices and policies across the Indian subcontinent. This disparity of health systems across India was highlighted in a study assessing COI across five resource-poor locations in India. The study concluded that there is no uniform model to establish the cost of healthcare across the subcontinent.[22] Therefore, a central mechanism of disease control is not applicable, as resource availability differs between the urban and rural parts of India. It is difficult to devise and implement a single healthcare policy for the entire country. The optimal way of handling this issue is to have specific health policy in each state, considering the factors such as health state, income, education, and climatic conditions.

The pharmacoeconomic studies published from India have been few but the trend has increased since 2007. Most studies from India were published in foreign journals and the authors of most model-based studies were from outside India. These studies utilized appropriate model parameters and analyses, and were therefore categorized to be of high quality as per the QHES instrument. There is still a paucity of health economic studies conducted in India by Indian healthcare providers. The evidence from literature is best published in Indian journals, so that they are readily accessed by the medical community in India.

This systematic review has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most recent systematic review on this important topic, particularly in the Indian context. Our review identified different health economic studies conducted across India. This review focused on utilization of healthcare resources in India and the measures to be taken to provide better healthcare for a broader population. Government agencies and industry play a key role toward achieving this goal. The present review has included a broad range of evidence across different studies, but the heterogeneity of data on pharmacoeconomic studies, different study designs, and varying disease types has limited the comparability across studies. One possible limitation of this review could be the quality of studies included. Majority of the studies were retrospective in nature, and such studies are prone to bias. However, as with any review of literature, a balance has to be found between having too stringent search criteria and too loose a search strategy to fulfill the question of interest, and we have attempted to sketch a baseline understanding of the situation in India for this pertinent area through this systematic review.

In conclusion, this review identified various patterns of health economic studies in India. Majority of the CEA studies conducted in recent years were of high quality, but overall, the model-from studies were limited and conducted by researchers based outside India. Utilization of healthcare resources in India is inadequately assessed and needs to be relevant to the different healthcare settings in India.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Hemlata Shukla, Capita India Private Limited for providing editorial support to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by Pfizer India Private Limited, Mumbai, India. The corresponding author was employed with Pfizer at the time of conduct and analysis of this study. Figures in editable file are uploaded on the site.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walley T, Haycox A. Pharmacoeconomics: Basic concepts and terminology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:343–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahuja J, Gupta M, Gupta AK, Kohli K. Pharmacoeconomics. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarn YH, Hu S, Kamae I, Yang BM, Li SC, Tangcharoensathien V, et al. Health-care systems and pharmacoeconomic research in Asia-Pacific region. Value Health. 2008;11(Suppl 1):S137–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinath Reddy K, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil AV, Somasundaram KV, Goyal RC. Current health scenario in rural India. Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10:129–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ofman JJ, Sullivan SD, Neumann PJ, Chiou CF, Henning JM, Wade SW, et al. Examining the value and quality of health economic analysis: Implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9:53–61. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggarwal R, Ghoshal UC, Naik SR. Assessment of cost-effectiveness of universal hepatitis B immunization in a low-income country with intermediate endemicity using a Markov model. J Hepatol. 2003;38:215–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy NS, Nandakumar BS, Pruthvish S, George PS, Mathew A. Disability adjusted life years for cancer patients in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansal VK, Misra MC, Babu D, Singhal P, Rao K, Sagar R, et al. Comparison of long-term outcome and quality of life after laparoscopic repair of incisional and ventral hernias with suture fixation with and without tacks: A prospective, randomized, controlled study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3476–85. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pho MT, Swaminathan S, Kumarasamy N, Losina E, Ponnuraja C, Uhler LM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis preventive therapy for HIV-infected individuals in southern India: A trial-based analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meheus F, Balasegaram M, Olliaro P, Sundar S, Rijal S, Faiz MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of combination therapies for visceral leishmaniasis in the Indian subcontinent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(pii):e818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kermode M, Devine A, Chandra P, Dzuvichu B, Gilbert T, Herrman H. Some peace of mind: Assessing a pilot intervention to promote mental health among widows of injecting drug users in north-east India. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee T, Pensi T, Banerjee D. HRQoL in HIV-infected children using PedsQL 4.0 and comparison with uninfected children. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:803–12. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das S, Mukherjee A, Lodha R, Vatsa M. Quality of life and psychosocial functioning of HIV infected children. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:633–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chirivella S, Rajappa S, Sinha S, Eden T, Barr RD. Health-related quality of life among children with cancer in Hyderabad, India. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:1231–5. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai PR, Chandwani HS, Rascati KL. Assessing the quality of pharmacoeconomic studies in India: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:749–62. doi: 10.2165/11590140-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bender MA, Kumarasamy N, Mayer KH, Wang B, Walensky RP, Flanigan T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tenofovir as first-line antiretroviral therapy in India. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:416–25. doi: 10.1086/649884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel KJ, Kedia MS, Bajpai D, Mehta SS, Kshirsagar NA, Gogtay NJ. Evaluation of the prevalence and economic burden of adverse drug reactions presenting to the medical emergency department of a tertiary referral centre: A prospective study. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sur D, Chatterjee S, Riewpaiboon A, Manna B, Kanungo S, Bhattacharya SK. Treatment cost for typhoid fever at two hospitals in Kolkata, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:725–32. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i6.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John KR, Daley P, Kincler N, Oxlade O, Menzies D. Costs incurred by patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in rural India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dranitsaris G, Truter I, Lubbe MS, Sriramanakoppa NN, Mendonca VM, Mahagaonkar SB. Improving patient access to cancer drugs in India: Using economic modeling to estimate a more affordable drug cost based on measures of societal value. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:23–30. doi: 10.1017/S026646231000125X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dror DM, van Putten-Rademaker O, Koren R. Cost of illness: Evidence from a study in five resource-poor locations in India. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:347–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]