Abstract

IMPORTANCE

The impact of the substantial growth in for-profit hospices in the United States on quality and hospice access has been intensely debated, yet little is known about how for-profit and nonprofit hospices differ in activities beyond service delivery.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the association between hospice ownership and (1) provision of community benefits, (2) setting and timing of the hospice population served, and (3) community outreach.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Cross-sectional survey (the National Hospice Survey), conducted from September 2008 through November 2009, of a national random sample of 591 Medicare-certified hospices operating throughout the United States.

EXPOSURES

For-profit or nonprofit hospice ownership.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Provision of community benefits; setting and timing of the hospice population served; and community outreach.

RESULTS

A total of 591 hospices completed our survey (84% response rate). For-profit hospices were less likely than nonprofit hospices to provide community benefits including serving as training sites (55% vs 82%; adjusted relative risk [ARR], 0.67 [95% CI, 0.59–0.76]), conducting research (18% vs 23%; ARR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.46–0.99]), and providing charity care (80% vs 82%; ARR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.80–0.96]). For-profit compared with nonprofit hospices cared for a larger proportion of patients with longer expected hospice stays including those in nursing homes (30% vs 25%; P = .009). For-profit hospices were more likely to exceed Medicare’s aggregate annual cap (22% vs 4%; ARR, 3.66 [95% CI, 2.02–6.63]) and had a higher patient disenrollment rate (10% vs 6%; P < .001). For-profit were more likely than nonprofit hospices to engage in outreach to low-income communities (61% vs 46%; ARR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.05–1.44]) and minority communities (59% vs 48%; ARR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.02–1.38]) and less likely to partner with oncology centers (25% vs 33%; ARR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.44–0.80]).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Ownership-related differences are apparent among hospices in community benefits, population served, and community outreach. Although Medicare’s aggregate annual cap may curb the incentive to focus on long-stay hospice patients, additional regulatory measures such as public reporting of hospice disenrollment rates should be considered as the share of for-profit hospices in the United States continues to increase.

The US hospice industry has changed dramatically in the past 2 decades because of the growth of for-profit hospices. Whereas only 5% of hospices were for-profit in 1990, as of 2011, approximately 51% of hospices were for-profit.1 Between 2000 and 2009, 4 of 5 hospices that entered the US market were for-profit, and more than 40% of hospices operating in 2000 had changed ownership during that same decade.2 The impact of the growth of for-profit hospices on both quality and access to hospice care has been intensely debated3–13 because of both the vulnerability of dying patients and their families and the unique role that the hospice industry—and nonprofit hospices, in particular—have played in the social movement to improve care for the terminally ill in the United States.

Hospice is a unique system of care in the United States. As codified under Medicare, hospice provides a package of clinical and psychosocial services to Medicare beneficiaries who are considered to have terminal diagnoses (ie, a life expectancy of ≤6 months) and who are willing to forgo curative treatments. Hospices have played a unique role in American medicine by serving as a driving force for social change and shifting norms regarding care at the end of life for terminally ill patients and their families. Through activities such as community outreach and education, clinical training, research, public advocacy, and charity care, hospices have made considerable contributions to improvements in the care of people who are dying and their families and have helped reduce barriers to end-of-life care. Historically, nonprofit hospices have been at the forefront of these efforts.14–16

Prior comparisons of for-profit and nonprofit hospices have focused almost exclusively on the service delivery component of hospice, and this research has found a number of differences between the sectors. For-profit hospices have been found to provide a narrower range of services to patients and families,7 to offer less comprehensive bereavement services to families,8 to have less professionalized staff,9 and to have lower staff to patient ratios.17 In addition, for-profit hospices have been found to have longer average length of stay for their patients and to be more likely to care for patients with noncancer diagnoses than nonprofits.10,11 Little research has examined the impact of hospice ownership on end-of-life care activities beyond service delivery and thus on the broader ways that hospices can affect Americans’ health care.

Accordingly, we examined the association between hospice ownership and (1) the provision of community benefits, (2) the setting and timing of the hospice population served, and (3) community outreach. We used data from the National Hospice Survey, which is a survey of a random sample of hospices across the country (591 hospices; response rate, 84%) regarding their programs, services, and staffing and was conducted during 2008 through 2009. Findings from these data will help identify the potentially differing contributions of nonprofit and for-profit hospices to the community and to the patients and families living with serious illness.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

All research procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Yale University. We designed and fielded a national survey of a random sample of 914 hospices operating in the United States from September 2008 to November 2009. We chose our random sample of hospices from the 2006 Medicare Provider of Services (POS) file (3036 hospices), which includes all hospices that participate in the Medicare program (approximately 93% of all hospices nationally).18 In addition, when the 2008 Medicare POS file (3306 hospices) became available, we augmented our sample with hospices newly operating between 2006 and 2008. We estimated that 18% of hospices had been operating for 2 years or less, and thus we randomly selected 139 hospices (0.18 × 775) from the 2008 Medicare POS file to establish a total sample of 914 hospices (775 hospices from the 2006 Medicare POS file and 139 younger hospices from the 2008 Medicare POS file). Introductory e-mails were sent to hospices inviting their medical directors to participate in the survey, and a follow-up e-mail included a link to the web-based survey.

Survey Instruments and Measures

Outcome Variables

We evaluated the association between hospice ownership and (1) the provision of community benefits, (2) the setting and timing of the hospice population served, and (3) community outreach. To develop the survey questions, we conducted semi-structured interviews with personnel at 16 hospices to ascertain views about numerous aspects of the survey including community benefits and outreach. The hospices were purposefully chosen to achieve diversity geographically and along other hospice characteristics (ie, ownership type, religious affiliation, size).

To assess the provision of community benefits, survey respondents were asked if their hospice serves as a training site for medical students, residents, nursing students, social work students, or other practitioners; if their hospice conducts or collaborates in research for publication (ie, the hospice funds and conducts research itself or allows academic researchers to engage its patients and families in larger studies); and what is the annual percentage of their hospice’s patients who are charity care.

To assess the setting and timing of the hospice population served, survey respondents were asked for the number of patients per day the hospice cared for in each setting (home, inpatient hospice, nursing home, and assisted-living facility). We also asked for the percentage of the hospice’s patients who remained enrolled with the hospice until death. To measure the hospice’s likelihood of enrolling patients very early in the terminal phase of disease, we asked in how many of the past 5 fiscal years the hospice exceeded the Medicare aggregate annual cap (response range, 0–5 years). The Medicare aggregate annual cap is designed to prevent hospices from enrolling patients in the preterminal phase of disease by requiring hospices to return Medicare reimbursement if they have a high proportion of patients who have length of stay longer than the Medicare Hospice Benefit’s “terminal” period (ie, >6 months). The cap amount ($25 337 in 2012) is essentially Medicare’s per patient per diem reimbursement amount multiplied by 180 days. If a hospice’s total annual Medicare reimbursement exceeds the cap multiplied by the annual number of patients the hospice served, it must repay the excess to the Medicare program.6

To measure community outreach, survey respondents were asked if their hospice sought to attract patients through outreach to clinicians, hospital discharge planners, nursing homes, home health agencies, senior centers, faith-based groups, low-income communities, racial/ethnic minority communities, and the general public. Hospices were also asked if they partner with the following to provide services to the community: oncology centers, adult day care centers, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS organizations, faith-based organizations, and senior service organizations. These categories were chosen based on in-depth interviews with hospices during our survey development period and represent the organizations and groups hospices considered the most germane and prevalent to include in survey questions regarding outreach and partnerships.

Independent Variables

The survey included questions regarding hospice characteristics including hospice ownership (nonprofit, for-profit, or government owned), size (number of patients per day), whether the hospice was part of a chain of hospices, whether the hospice was vertically integrated (ie, affiliated with) a hospital, nursing home, home health agency or other health care organization, and census region.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the proportion of hospices that reported each of the outcome measures in our survey. We estimated the bivariate associations between hospice ownership and each out-come measure using χ2 statistics and t tests, as appropriate. We estimated adjusted risk ratios using modified Poisson regression models with a robust error variance19 for each outcome. To estimate the independent effect of hospice ownership on study outcomes, regression models controlled for the following hospice characteristics considered to be potential confounders based on prior literature,5–8,20–22 hospice size, whether the hospice was part of a chain of hospices, whether the hospice was vertically integrated, and census region. Given the low prevalence of nonprofit hospices that were chains (8%), we also estimated multivariate models excluding chain status, and the results were not materially different. We performed all analyses using Stata software, version 11 (StataCorp).

Results

Study Population

Of the total 914 hospices randomly selected for the survey, 208 were excluded because they no longer provided hospice care or had closed, resulting in 706 eligible hospices. Of those 706 hospices, 591 completed our survey, a response rate of 84%. Nonprofit hospices were more likely to respond (89% response rate) than were government-owned (86% response rate) and for-profit hospices (79% response rate) (P = .004 for χ2 comparison). There were no significant differences in response rates by other hospice characteristics. Characteristics of responding hospices are given in Table 1. There was significant variation in the proportion of hospices that were for-profit compared with nonprofit by both chain status and region.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Hospices

| Hospice Characteristic | Hospices, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 591) | For-Profit (n = 285) | Nonprofit (n = 283) | |

| Size, No. of patients per daya | |||

| >20 | 156 (26) | 68 (24) | 77 (27) |

| 20–49 | 151 (26) | 75 (26) | 70 (25) |

| 50–99 | 152 (26) | 87 (31) | 64 (23) |

| ≥100 | 127 (21) | 55 (19) | 72 (25) |

| Missing | 5 (1) | ||

| Hospice is a member of a chainb | 144 (24) | 120 (42) | 24 (8) |

| Hospice is vertically integrateda | 143 (24) | 63 (22) | 78 (28) |

| Census regionb | |||

| New England | 28 (5) | 8 (3) | 20 (7) |

| Middle Atlantic | 40 (7) | 7 (2) | 33 (12) |

| East North Central | 92 (16) | 29 (10) | 58 (20) |

| West North Central | 69 (12) | 21 (7) | 44 (16) |

| South Atlantic | 96 (16) | 50 (18) | 43 (15) |

| East South Central | 62 (10) | 41 (14) | 19 (7) |

| West South Central | 101 (17) | 74 (26) | 23 (8) |

| Mountain | 51 (9) | 29 (10) | 18 (6) |

| Pacific | 52 (9) | 26 (9) | 25 (9) |

Not significant (P > .05).

Significant (P < .01).

Provision of Community Benefits

For-profit compared with nonprofit hospices were less likely to serve as training sites (55% vs 82%; adjusted relative risk [ARR], 0.67 [95% CI, 0.59–0.76]), and for-profit hospices were less likely to conduct research for publication (18% vs 23%; ARR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.46–0.99]) (Table 2). For-profit hospices were also significantly less likely to provide charity care (80% vs 82%; ARR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.80–0.96]), although the magnitude of this difference was small and more than 80% of all hospices reported some charity care.

Table 2.

Provision of Community Benefits, by Hospice Ownership

| Provision | Unadjusted % | P Value | ARR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For-Profit Hospices | Nonprofit Hospices | ||||

| Hospice is a training site | 55 | 82 | <.001 | 0.67 (0.59–0.76) | <.001 |

| Hospice conducts research for publication | 18 | 23 | .23 | 0.67 (0.46–0.99) | .047 |

| Hospice provides charity care | 80 | 82 | .64 | 0.88 (0.80–0.96) | .006 |

Abbreviation: ARR, adjusted relative risk.

Adjusted models include hospice size, chain ownership, vertical integration and census region.

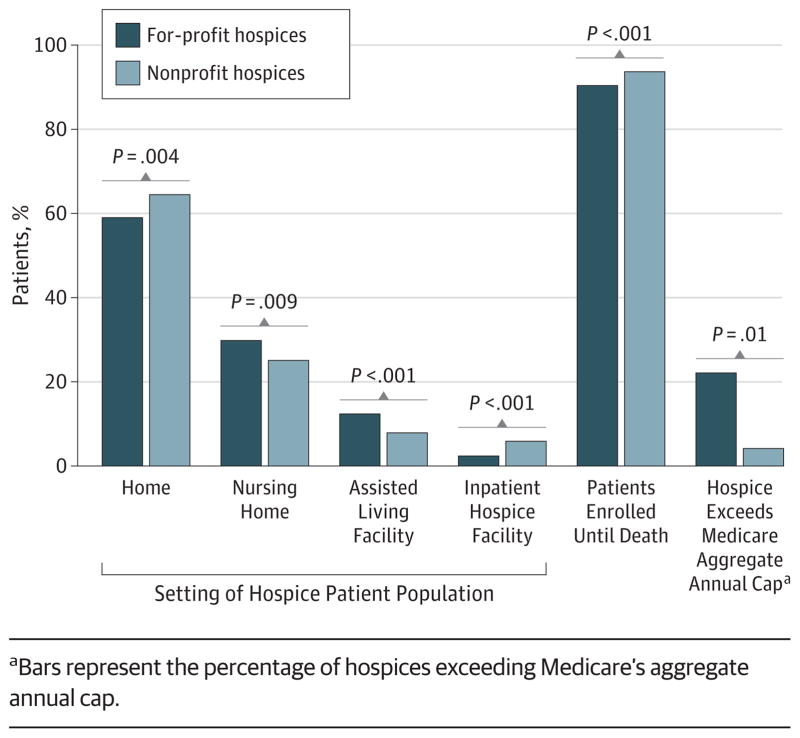

Setting and Timing of Hospice Population Served by Hospices

We found that for-profit compared with nonprofit hospices served a significantly greater proportion of their patients in the nursing home (30% vs 25%, respectively; P = .009) and in assisted living facilities (12% vs 8%, respectively; P < .001) and a smaller percentage of their patients at home (59% vs 64%, respectively; P = .004) and in an inpatient hospice (2% vs 4%, respectively; P < .001) (Figure 1). For-profit compared with nonprofit hospices had a lower percentage of patients who remained under their care until death (90% vs 94%, respectively; P < .001) and thus a higher patient disenrollment rate (10% vs 6%, respectively). For each comparison, ownership differences remained significant after adjusting for hospice size, whether the hospice was part of a chain of hospices, whether the hospice was vertically integrated, and census region.

Figure 1. Setting and Timing of Hospice Population Served, by Hospice Ownership.

aBars represent the percentage of hospices exceeding Medicare’s aggregate annual cap.

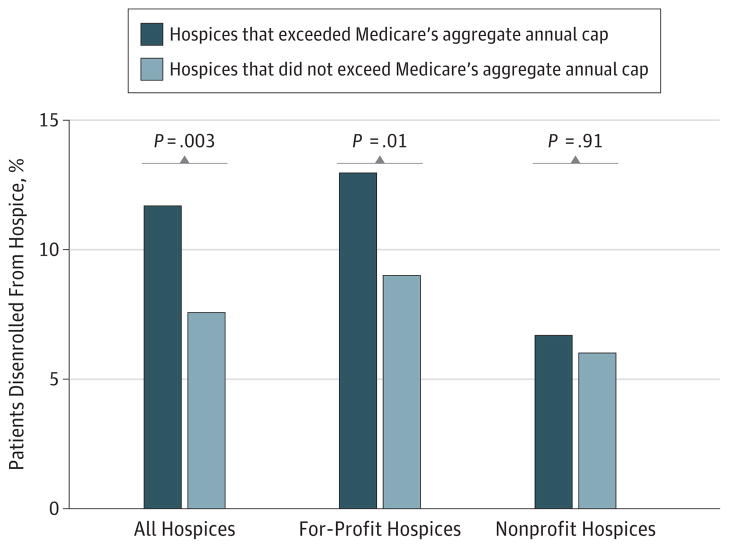

For-profit compared with nonprofit hospices were also more than 3 times as likely to exceed Medicare’s aggregate annual cap (ARR, 3.66 [95% CI, 2.02–6.63]). Twenty-two percent of for-profit hospices compared with 4% of nonprofit hospices reported exceeding Medicare’s aggregate annual cap at least once in the past 5 years (P < .001). For-profit hospice ownership was the only hospice characteristic that was significantly associated with exceeding the Medicare cap. In addition, for-profit hospices that reported exceeding the Medicare cap had higher average patient disenrollment rates compared with for-profit hospices that did not report exceeding the Medicare cap (13.0% vs 8.9%, P = .01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of Patients Disenrolled From Hospice by Hospice Ownership and Exceeding the Medicare Aggregate Annual Cap

Community Outreach

Although most of the hospices engaged in outreach, nonprofit and for-profit hospices differed in their foci for these efforts (Table 3). For-profit compared with nonprofit hospices were significantly more likely to target senior centers (88% vs 79%; ARR, 1.12 [95% CI, 1.04–1.20]), home health agencies (88% vs 75%; ARR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.08–1.26]), low-income communities (61% vs 46%; ARR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.05–1.44]) and racial/ethnic minority communities (59% vs 48%; ARR, 1.18 [95% CI, 1.02–1.38]) in order to attract patients and families to their hospice, although the magnitude of these differences were generally small. For-profit hospices were less likely than nonprofit hospices to partner with oncology centers (25% vs 33%; ARR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.44–0.80]) and with faith-based organizations (36% vs 47%; ARR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.56–0.89]) to provide services.

Table 3.

Community Outreach by Hospice Ownership

| Community Outreach | All Hospices, No. (%)(N = 591) | Unadjusted % | P Value | ARR (95% CI)a | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For-Profit Hospices | Nonprofit Hospices | |||||

| Hospice actively targets the following with outreach to attract patients | ||||||

| Physicians/clinicians | 572 (97) | 97 | 97 | .80 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | .04 |

| Hospital discharge planners | 563 (95) | 95 | 96 | .69 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | .34 |

| General public | 547 (93) | 92 | 94 | .35 | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | .92 |

| Nursing homes | 544 (92) | 94 | 92 | .32 | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | .08 |

| Senior centers | 487 (82) | 88 | 79 | .004 | 1.12 (1.04–1.20) | .002 |

| Home health agencies | 477 (81) | 88 | 75 | <.001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.26) | <.001 |

| Faith-based groups | 439 (74) | 77 | 73 | .23 | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | .12 |

| Low-income communities | 315 (53) | 61 | 46 | <.001 | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | .01 |

| Racial/ethnic minority communities | 313 (53) | 59 | 48 | .006 | 1.18 (1.02–1.38) | .03 |

| Hospice has partnered with the following to provide services to patients | ||||||

| Oncology centers | 169 (29) | 25 | 33 | .046 | 0.59 (0.44–0.80) | .001 |

| Adult day care centers | 137 (23) | 27 | 20 | .06 | 1.19 (0.84–1.67) | .33 |

| HIV/AIDS organizations | 67 (11) | 12 | 11 | .72 | 0.80 (0.47–1.38) | .43 |

| Faith-based organizations | 237 (40) | 36 | 47 | .009 | 0.71 (0.56–0.89) | .003 |

| Senior service organizations | 300 (51) | 53 | 51 | .92 | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | .37 |

Abbreviations: ARR, adjusted relative risk; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Adjusted models include hospice size, chain ownership, vertical integration and census region.

Discussion

For-profit and nonprofit hospices differed in the provision of community benefits, the setting and timing of the population served, and in outreach to the community. Nonprofit hospices more frequently served as training sites and conducted research for publication. A marginally higher proportion of nonprofit compared with for-profit hospices provided charity care to patients. Hospice ownership also distinguished both the setting and timing of the hospice population served with for-profit hospices focusing on patients likely to maximize hospice revenue (eg, those with potentially longer lengths of hospice stay and those residing in institutions such as nursing homes or assisted-living facilities). The for-profit hospices’ focus on patients with potentially longer lengths of hospice stay was also evident in the more than 5-fold higher proportion of for-profit hospices compared with nonprofit hospices that exceeded Medicare’s aggregate annual cap.

Our findings regarding more training and research at nonprofit hospices have potentially long-term implications for the hospice industry. As a rapidly growing field, and one that involves a particularly complex skill set, the need for ongoing training is critical. Currently, there is an estimated shortage of approximately 12 000 hospice and palliative medicine physicians, and palliative medicine fellowship training programs are graduating only 180 fellows per year—a number that does not replace those retiring from the field.23 Training sites are key to building a workforce by providing sites for fellowship and mid-career training. The rapid pace with which the field is growing also makes ongoing research in the hospice setting critical to ongoing quality improvement. Given a dwindling nonprofit hospice sector, it is not clear how activities such as training and research will continue without incentives or requirements by Medicare. Training and research are important functions of health care providers across all disciplines, including hospice, and if for-profit hospices tend to not engage in these activities, it may be a loss to applied research and training in palliative care nationally.

Our finding that nonprofit hospices were more likely to serve patients in the home and in inpatient hospice facilities, while for-profit hospices were more likely to serve patients in nursing homes and assisted living facilities, supports the existing view5,13 that for-profit hospices focus on patients likely to have longer lengths of hospice stay and is consistent with a recent analysis11 using patient-level data. Although greater access to quality hospice care in settings such as nursing homes may benefit patients and families,24–27 the practice of selectively admitting patients with higher probability of long stays is concerning and was highlighted in a recent Medpac report.5 In 2011, the mean hospice length of stay was 149 days for patients residing in an assisted living facility, 111 days for patients in a nursing home, and 88 days for patients residing at home.6 Patients with longer length of hospice stay have been shown to be more profitable for hospices because of their lower average cost per day combined with Medicare’s fixed per diem hospice reimbursement, which accounts for 80% of hospice revenue, on average.1 Furthermore, home-based hospice care is typically more expensive than institution-based care, since hospice personnel time associated with travel and home visits is significantly greater than that required of providing hospice within institutions. Similarly, for home hospice patients, the hospice typically is responsible for providing the primary support for personal care needs in contrast to nursing homes and assisted-living facilities where such services are provided primarily by the institution. The fact that for-profit hospices were more than 3 times more likely than nonprofit hospices to exceed the Medicare aggregate annual cap suggests that the Medicare cap is effective in providing a deterrent to the tendency of for-profit hospices to enroll patients with long expected lengths of stay. If very few hospices exceeded the cap, one could argue that it is set too high to be a real deterrent for hospices. The fact that 22% of for-profit hospices exceeded the cap in the preceding 5 years suggests that it is at least a tangible consequence of their practices. The aggregate annual cap was established by Medicare as a regulatory measure to control length of hospice stay and is the only fiscal constraint on the growth of Medicare hospice expenditures. Under the cap, if a hospice’s total annual reimbursement from Medicare exceeds its total number of Medicare beneficiaries served multiplied by the cap amount ($25 337 in 2012), it must repay the excess to the Medicare program.6 Given Medicare’s per diem hospice reimbursement, exceeding the cap indicates a length-of-stay profile that is too long per the Medicare Hospice Benefit design. Although exceeding the cap could also result from having a higher proportion of patient days reimbursed at a higher level of care (eg, general inpatient care), that explanation is unlikely, given that more than 97% of days are reimbursed under the routine home care rate. In a recent MedPac report,6 hospices that exceed the cap are described as having “unusual utilization patterns” warranting further study. Our finding that for-profit hospices tended to exceed the cap suggests that length of stay is considerably longer than 6 months for a significant proportion of their patients.

Although earlier referral to hospice is generally considered beneficial for patients and families, the cap is intended to ensure that hospice remains focused on terminal care. Although the difference between for-profit and nonprofit hospices’ average patient disenrollment rate was small (4 percentage points), the higher disenrollment rate at for-profit hospices should be monitored, given recent evidence28 of poor outcomes for patients who disenroll including higher rates of emergency department admissions and hospital death. Hospice disenrollment may be initiated by either the patient (eg, if the patient wishes to pursue curative care, is dissatisfied with hospice, or moves away from the hospice’s service area) or the hospice (eg, if the patient no longer meets eligibility criteria). Our results suggest that patient disenrollment may be related to exceeding the Medicare aggregate cap, given that for-profit hospices that report exceeding the cap have higher disenrollment rates than for-profit hospices that do not report exceeding the cap—there is no comparable difference for nonprofit hospices. Public reporting of the patient disenrollment rate could act as an additional disincentive for targeting long-stay patients and was recently proposed as a reportable hospice quality measure by a technical expert panel of hospice clinicians and researchers.6 This type of public reporting has the potential to improve quality by, for example, reducing disenrollment of patients who want to continue hospice but require more expensive care. This is particularly true if hospices are required to report the reasons for patient disenrollment. It may also potentially reduce overall Medicare expenditures by decreasing hospitalizations and hospital death.28

Overall, a high proportion of hospices reported outreach activities across various settings and organizations. Although it may be that for-profit hospices are less likely to partner with oncology centers because patients with cancer are known to have shorter length of hospice stay,5 we lack data on the rationale for these strategies, and further research regarding these strategies is required. The fact that we found no ownership difference in outreach to nursing homes despite the finding that for-profit hospices served a larger percentage of their patients in the nursing home setting is likely because the overall rate of nursing home outreach was high (92%). The finding that for-profit hospices were more likely than nonprofit hospices to conduct outreach to low-income and racial/ethnic minority communities suggests that the growth of the for-profit sector may increase use of hospice by these groups and address concerns regarding disparities in hospice use. Additional studies of the quality of care delivered in these settings, however, are needed.

A limitation of this analysis is that data were self-reported by hospices and thus may over or underestimate the true prevalence of outcomes measured. Future studies linking reported outcomes with patient-level data regarding use of hospice are needed. A second limitation is that although we had a high overall survey response rate of 84% that did not significantly differ by years providing hospice care or region, our survey response rate differed somewhat by hospice ownership, and we could not test for differences in survey response rate by other hospice characteristics such as size. Third, although some of the outcomes in our study have been previously reported by Medpac, those reports are not published in peer-reviewed journals and thus may not be known to a wider audience. In addition, the hospice claims data used in their reports do not contain the range of information on hospice characteristics included in our survey and have no information on community benefits and outreach. Fourth, our survey did not include questions regarding the reasons for hospice disenrollment or why hospices did not engage in training and research activities. It could be that hospices were not asked to engage in these activities or that they were asked and refused. More research regarding these areas of community benefits is needed. Finally, our results are not generalizable to the 7% of hospices in the United States that do not participate in the Medicare program.

Conclusions

Although nonprofit hospices were the genesis of the hospice movement in the United States, hospice has transitioned to an industry dominated by for-profit health care providers. As this trend in for-profit dominance continues, alternatives for the provision of community benefits such as training and research should be considered. As described in a recent Med-Pac report to Congress,6 the fact that hospice length of stay varies by observable patient characteristics, such as setting of care and diagnosis,6 introduces the ability of hospice providers to focus on profitable patient groups, as suggested by our study results. Ongoing enforcement of Medicare’s aggregate annual cap as well as public reporting of hospice disenrollment rates may serve to curb those incentives.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant 1R01CA116398-01A2 from the National Cancer Institute (Dr Bradley); the John D. Thompson Foundation (Dr Bradley); and grant 1K99NR010495-01 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (Dr Aldridge).

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Author Contributions: Drs Aldridge and Bradley had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Aldridge, Schlesinger, Barry, Morrison, McCorkle, Bradley.

Acquisition of data: Aldridge, Schlesinger, Barry, Bradley.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Aldridge, Schlesinger, Barry, Morrison, McCorkle, Hürzeler, Bradley.

Drafting of the manuscript: Aldridge, Barry, Morrison, Bradley.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Aldridge, Schlesinger, Barry, Morrison, McCorkle, Hürzeler, Bradley.

Statistical analysis: Aldridge.

Obtained funding: Aldridge, Schlesinger.

Administrative, technical, and material support: Aldridge, Morrison, Hürzeler.

Study supervision: Aldridge, Schlesinger, Barry, Morrison, Bradley.

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. [Accessed February 2012];NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. 2011 http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2011_Facts_Figures.pdf.

- 2.Thompson JW, Carlson MD, Bradley EH. US hospice industry experienced considerable turbulence from changes in ownership, growth, and shift to for-profit status. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1286–1293. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Beneficiaries’ Access to Hospice. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Reforming the Delivery System. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2008. pp. 203–240. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare’s Payment Policy: Reforming Medicare’s Hospice Benefit. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2013. pp. 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson MD, Gallo WT, Bradley EH. Ownership status and patterns of care in hospice: results from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey. Med Care. 2004;42(5):432–438. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124246.86156.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry CL, Carlson MD, Thompson JW, et al. Caring for grieving family members: results from a national hospice survey. Med Care. 2012;50(7):578–584. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318248661d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherlin EJ, Carlson MD, Herrin J, et al. Interdisciplinary staffing patterns: do for-profit and nonprofit hospices differ? J Palliat Med. 2010;13(4):389–394. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindrooth RC, Weisbrod BA. Do religious nonprofit and for-profit organizations respond differently to financial incentives? the hospice industry. J Health Econ. 2007;26(2):342–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, McCarthy EP. Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA. 2011;305(5):472–479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz KA, Ettner SL, Rosenfeld KE, Carlisle DM, Leake B, Asch SM. Cash and compassion: profit status and the delivery of hospice services. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(4):507–514. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglehart JK. A new era of for-profit hospice care—the Medicare benefit. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2701–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson MD, Morrison RS, Bradley EH. Improving access to hospice care: informing the debate. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(3):438–443. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James N, Field D. The routinization of hospice: charisma and bureaucratization. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(12):1363–1375. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90145-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paradis LF, Cummings SB. The evolution of hospice in America toward organizational homogeneity. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27(4):370–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canavan ME, Aldridge Carlson MD, Sipsma HL, Bradley EH. Hospice for nursing homes: does ownership type matter?. Presented at: Gerontological Society of America 65th Annual Scientific Meeting; November 16, 2012; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. [Accessed February 2011];NHPCO facts and figures: hospice care in America. 2010 http://www.stjosephhospice.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Hospice_Facts_Figures_Oct-2010.pdf.

- 19.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlson MD, Barry C, Schlesinger M, et al. Quality of palliative care at US hospices: results of a national survey. Med Care. 2011;49(9):803–809. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822395b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Hospice characteristics and the disenrollment of patients with cancer. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(6):2004–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, McCorkle R, Bradley EH. Hospices’ enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(12):2690–2698. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupu D American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(6):899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, Gozalo P, Lapane K. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, Williams CS, Biola H, Zimmerman S. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baer WM, Hanson LC. Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and medicare expenditures for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(28):4371–4375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]