Abstract

Patient: Male, 71

Final Diagnosis: SIADH

Symptoms: Cachexia • confusion

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Percutaneous liver biopsy

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) is usually seen in pulmonary malignancies, central nervous system disorders, and secondary to medications. SIADH has very rarely been encountered in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Two cases were reported in Japan and 1 case in Spain after extensive investigation of the medical records.

Case Report:

We report a case of a 71-year-old man who presented with confusion, cachexia, and abdominal symptoms in the form of vomiting and abdominal discomfort. On the initial work-up, SIADH diagnosis was made. After an extensive work-up, the reason for SIADH turned out to be a newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma. The precipitating factor for the cancer was not identified by history or by work-up. No metastasis was identified. Liver functions were preserved but patient was severely malnourished.

Conclusions:

SIADH can occur as a para-malignant feature of the malignancy. In our case, it was related to the hepatocellular carcinoma, which is a malignancy very rare to cause SIADH.

MeSH Keywords: Inappropriate ADH Syndrome, Liver Neoplasms, Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Background

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH) is a disorder of impaired water excretion caused by the inability to suppress the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) [1]. ADH secretion primarily arises from the posterior pituitary gland, but it can be secreted by other sources. Although SIADH has been described in the setting of central nervous system disorders, secondary to medications, and in some malignancies [mainly small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma), and blood malignancies] [2–4], it is very rarely associated with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. There have only been 3 previous remotely reported cases of this association based on our comprehensive and extensive review of the literature [5–7]. We report a case of a Guatemalan man diagnosed with SAIDH in the setting of primary hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case Report

Patient information

We report on a 71-year-old Guatemalan man with no reported past medical history.

Family history was not significant for any known malignancy. Social history was significant for long-term heavy smoking history but he quit 1 year before presentation. Alcohol drinking was heavy but limited to weekends and no complications from alcohol overuse were known by history.

Objectives for case reporting

SIADH can be secondary to some malignancies but is rarely reported secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma. Adding this case report to the 3 previously reported cases in the medical history records indicates SIADH as a rare complication secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Main medical problem

SIADH.

Coexisting diseases

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Newly discovered uncontrolled hypertension.

Case presentation

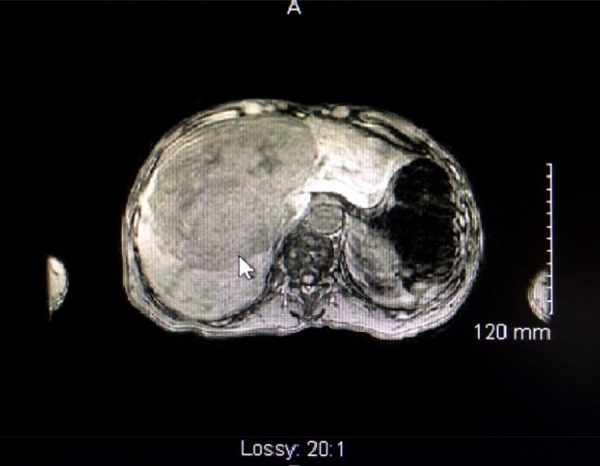

Our patient presented with persistent nausea, non-bilious vomiting, and vague abdominal discomfort, which commenced a few days prior to admission. The patient was cachectic and confused. He had elevated blood pressure. Laboratory findings showed an initial serum sodium level of 115 mmol/L, chloride of 77 mmol/L, and serum osmolarity of 246 mOsm/L. Urine osmolarity was 514 mOsm/L and urine sodium was 152 mmol/L. BUN was elevated at 8.6 mmol/L but serum creatinine and uric acid levels were normal at 80.4 umol/L and 232 umol/L, respectively. No acid-base disturbance was detected. LDH level was normal in blood. Chest x-ray did not reveal any suspected lung mass or pathology. CT of the chest demonstrated a 2-mm calcified nodule in the left upper lobe, likely a consequence of prior granulomatous infection, and scattered foci of emphysema bilateral lungs in a predominantly centri-lobular distribution. CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a large, heterogenous hepatic mass lesion present within the right hepatic lobe, measuring approximately 11.8×13.8×10.2 cm with marked compression of the IVC and concomitant dilatation of the main pancreatic duct at the level of the pancreatic body, measuring up to 3 mm in maximal diameter (Figure 1). MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with gadolinium was done and confirmed the previous liver findings.

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis showing liver mass (presented by the arrow).

To correct an assumed hypovolemic hyponatremia, we administered normal saline infusion at 100 ml/hour as a total of 1 liter total in 6 hours. Overnight, the sodium level was noted to have dropped to 110 mmol/L, with serum osmolarity decreasing to 234 mOsm/L. Thereafter, water restriction was instituted with initiation of hypertonic saline infusion in place of the normal saline. The patient was admitted directly to the intensive care unit. A CT of the brain was unremarkable. Tumor markers CEA, AFP, and CA-9-19 all returned within normal limits. TSH and cortisol levels were normal, as were the B-natriuretic peptide, ammonia level, and basic coagulation studies. Liver function tests showed normal hepatic synthetic function and only a marginal elevation of liver enzymes and bilirubin level. Hepatitis viral panel showed no reactivity. Blood count only showed mild anemia, with normal white cell count and platelet count. There was negative occult blood test in stool.

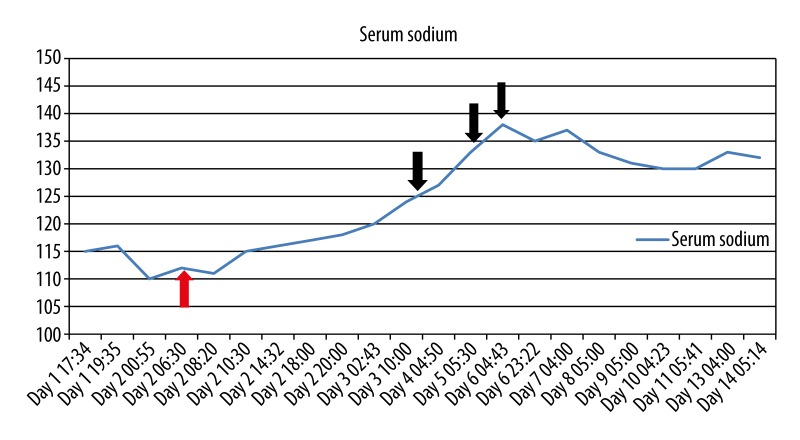

The sodium level rose in response to water restriction and hypertonic saline. The latter was stopped after the sodium level reached 120 mmol/L. The patient’s confusion was improving slightly. To promote free water excretion, the ADH V2 receptor antagonist, Tolvaptan, was initiated 24 hours later and was continued for 3 consecutive days. Sodium levels were monitored several times daily. Return to normal sodium levels was observed after 3 days of Tolvaptan therapy. A diagnosis of SIADH was made, given the clinical course, laboratory findings, and response to appropriate management. ADH level was not requested in blood or urine because the laboratory findings before and after hypertonic saline and Tolvaptan administration (Figure 2) were satisfactory for SIADH diagnosis. However, ADH level measurement is time consuming, expensive, and of less importance for confirmation of SIADH. The patient was transferred to the regular medical floor after his sodium level was more than 130 mmol/L. Serum osmolarity at that time increased to 267 mmol/L. The patient’s blood pressure was elevated during the hospital course and he was given nicardipine infusion, which was later shifted to oral amlodipine and metoprolol. An ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was done when the patient was deemed medically stable.

Figure 2.

Graph of the serum sodium levels during the hospital course before and after intervention by the managing physicians. Red arrow indicates the day that hypertonic saline infusion was given. Black arrows indicate the days on which tolvaptan was given.

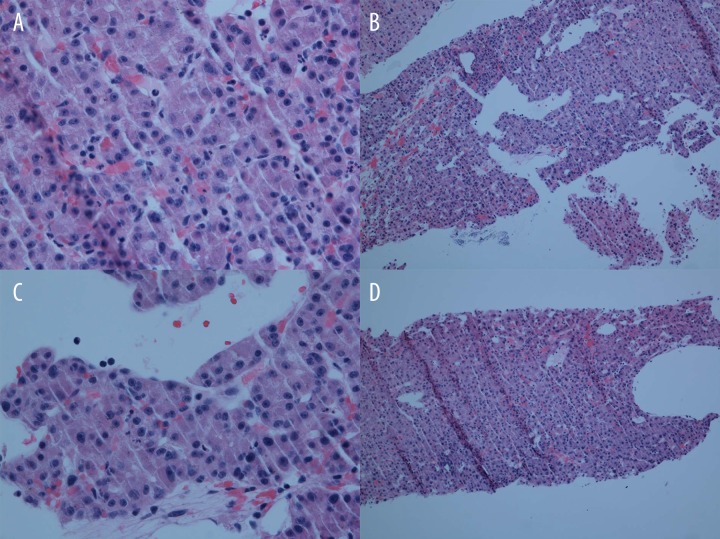

Later in the hospital course, dextrose 5% with normal saline was given at 70 ml/hour because the patient was not eating due to poor appetite and some residual confusion. Daily sodium levels following the infusion of the above fluid revealed mild reduction but remained above 130 mmol/L. Workup for dementia was done, including HIV, ANA, RPR, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Results returned unremarkable. Liver biopsy revealed a diagnosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma (Figure 3). An oncology consult was obtained and therapeutic options were discussed. However, prognosis was poor given the age, persistent confusion, and significant malnutrition. The family expressed desire to bring the patient back to his country of origin. He was thus discharged at his family’s request.

Figure 3.

Histopathologic specimen from the liver biopsy. 10×: A well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma with cells in a trabecular pattern and forming pseudo glands. 40×: Malignant hepatocytes with prominent nucleoli and some intracytoplasmic bile. The arrow highlights endothelial wrapping of the tumor cells, which is a feature of HCC.

Discussion

SIADH is associated with clinical hyponatremia in the setting of several underlying medical conditions. In the setting of malignancy, it is primarily associated with small-cell carcinoma of the lungs, and much less with other lung tumors. Schwartz’s hypothesis suggested that small-cell carcinoma produced some quantity of antidiuretic hormone, which was later found to consist of arginine vasopressin (AVP) by Bleich HL in 1976. Bleich also discovered the AVP-regulated water channels in the kidneys, which were later termed “aquaporins”. Schwartz’s hypothesis was proven by detecting ectopic AVP in small-cell carcinoma [8–10]. This hypothesis was further confirmed by expression analysis of the AVP-NP II gene, which controls the production of AVP, in small-cell carcinoma cells. These findings established the well accepted mechanism of action of SIADH caused by small-cell carcinoma [11–13]. Many researchers have found the AVP gene not only in small-cell carcinoma but also in undifferentiated carcinoma [14] and anaplastic carcinoma [15]. However, they have failed to find the AVP gene in squamous cell carcinoma [15,16].

After exhaustively exploring all the likely etiologies of SIADH in our patient, we have discovered in our literature search that there is no other possible link to SIADH than the patient’s coexistent newly diagnosed primary hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hyponatremia due to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) is associated with significant morbidity [17], mortality [18–21], and increased length of hospital stay. With severe hyponatremia (plasma sodium less than 120 mmol/l), there is an exponential increase in mortality, with death rates of 50% reported as plasma sodium concentration falls below 115 mmol/L [22,23]. Although ADH level was not measured in blood or urine in our case, different guidelines for confirmatory laboratory diagnosis of SIADH depend mainly on the serum and urine electrolytes and osmolarity and the changes after administration of hypertonic saline and tolvaptan, with little role of measurement of ADH levels [23–25].

One of the problems that our case confronted was the newly discovered uncontrolled hypertension that was controlled first by intravenous nicardipine that was shifted to PO amlodipine. The patient had a normal B-type NP level and did not exhibit signs of acute diastolic heart failure or any end-organ damage secondary to the uncontrolled hypertensive episode that was controlled adequately. Echocardiogram showed ejection fraction 56.1% with mild concentric left ventricle hypertrophy. A chest X-ray was done and did not show any signs of congestive heart failure or pleural effusion. This hypertension was not known to be new- or old-onset because the patient did not have a history of hypertension and was not on any medication, nor was he regularly seeing a primary care physician.

The para-neoplastic syndromes (PNS) that have been usually associated with HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) include hyper-cholesterolemia, hypercalcemia, erythrocytosis, hypoglycemia, demyelinating disease, pemphigus, polyarthritis, encephalomyelitis, and thrombocytosis [26–34]. The most common PNS associated with HCC are hypercholesterolemia, hypercalcemia, hypoglycemia, and erythrocytosis [35]. Para-neoplastic erythrocytosis is believed to occur as a result of increased tumor erythropoietin produced by the HCC or as a compensatory response to local hypoxia produced by tumor necrosis [36–39]. ADH secretion from hepatocellular carcinoma can be as a response to the tumor burden and the stress associated with that burden. This can raise the question about the possible mechanism of SIADH in this case in a similar way to other known para-neoplastic syndromes known in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Despite a major association of ectopic ADH secretion with SCLC and head and neck tumors, a broad spectrum of malignant tumors have also been reported to cause SIADH; however, most of these observations have been in case reports of very few patients and include such tumors as olfactory neuroblastomas, small-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas, undifferentiated carcinoma, and sarcomas that result in ectopic ADH production [39]. SIADH secondary to gastrointestinal malignancies is uncommon. A 1985 case report presented with SIADH secondary to adenocarcinoma of the colon [40]. Another case report was found with SIADH secondary to gastric carcinoma that was surgically resected and the SIADH resolved after that surgical resection [41]. Another case was a diagnosis of SIADH secondary to esophageal small-cell carcinoma [42].

Conclusions

SIADH can be secondary to unexpected causes. In our case, it was surprising to have it secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma, given that no other causes could be identified. In our reported case, the patient had locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with no evidence of liver cirrhosis or distant metastasis. This is a reminder that SIADH is a rare para-neoplastic syndrome secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma. This means that SIADH can always unexpectedly happen in any kind of malignancy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Dongming Gu, resident of the Department of Pathology, Monmouth Medical Center, NJ for the preparation of the pathology slide pictures.

Footnotes

Statement

There is no conflict of interest regarding the case report.

Financial funding is self-funding.

References:

- 1.Rose BD, Post TW. Clinical Physiology of Acid-Base and Electrolyte Disorders. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 703.p. 729. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Devaney KO. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion associated with head and neck cancers: review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:878. doi: 10.1177/000348949710601014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tnalmi YP, Wolf GT, Hoffman HT, Krause CJ. Elevated arginine vasopressin levels in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:317. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorensen JB, Andersen MK, Hansenn HH. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in malignant disease. J Intern Med. 1995;238:97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muela Molinero A, Ballesteros del Río B, Nistal de Paz F, Jorquera Plaza F. [Hepatocellular carcinoma producing syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion] Med Clin (Barc) 2003;121(10):396. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(03)73959-1. [in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda S, Okamoto K, Takahashi S, et al. [Primary hepatoma associated with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone] Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;76(7):1083–86. doi: 10.2169/naika.76.1083. [in Japanese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamura M, Tanahashi T, Murai T, Yamakita N. [A case of hepatocellar carcinoma associated with syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;95(10):1147–50. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amatruda TT, Jr, Mulrow PJ, Gallagher JC, Sawyer WH. Carcinoma of the lung with inappropriate antidiuresis demonstration of antidiuretic-hormone-like activity in tumor extract. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:544–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196309122691102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich HL, Boro ES. Antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(12):659–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609162951207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz WB, Bennett W, Curelop S, Bartter FC. A syndrome of renal sodium loss and hyponatremia probably resulting from inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1957;23(4):529–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(57)90224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson BE, Chute JP, Rushin J, et al. A prospective study of patients with lung cancer and hyponatremia of malignancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1669. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.96-10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amatruda TT, Jr, Mulrow PJ, Gallagher JC, Sawyer WH. Carcinoma of the lung with inappropriate antidiuresis, demonstration of antidiuretic-hormone-like activity in tumor extract. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:544–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196309122691102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sausville E, Carney D, Battey J. The human vasopressin gene is linked to the oxytocin gene and is selectively expressed in a cultured lung cancer cell line. J Biol Chem. 1985;60(18):10236–41. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavanagh BD, Halperin EC, Rosenbaum LC, et al. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone in a patient with carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Cancer. 1992;69(6):1315–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920315)69:6<1315::aid-cncr2820690602>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krmar RT, Ferraris JR, Ruiz SE, et al. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone in nasopharynx carcinoma. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11(4):502–3. doi: 10.1007/s004670050328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo M, Bediako EO, Akca O. Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH) Secretion Caused by Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Nasopharynx: Case Report. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1(2):110–12. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2008.1.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbalis J. Hyponatraemia, Water and Salt Homeostasis in Health and Disease. 1st ed. London: Baillie’re Tindall; 1989. pp. 499–530. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill G, Huda B, Boyd A, et al. Characteristics and mortality of severe hyponatraemia – a hospital-based study. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;65:246–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sajadieh A, Binici Z, Mouridsen MR, et al. Mild hyponatremia carries a poor prognosis in community subjects. Am J Med. 2009;122:679–86. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stelfox HT, Ahmed SB, Khandwala F, et al. The epidemiology of intensive care unit-acquired-hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia in medical-surgical intensive care units. Crit Care. 2008;12:162. doi: 10.1186/cc7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waikar SS, Mount DB, Curhan GC. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2009;122:857–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherlock M, O’Sullivan E, Agha A, et al. The incidence and pathophysiology of hyponatraemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;64:250–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherlock M, Thompson CJ. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone: current and future management options. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:13–18. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith DM, McKenna K, Thompson CJ. Hyponatraemia. Clin Endocrinol. 2000;52:667–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decaux G, Musch W. Clinical Laboratory Evaluation of the Syndrome of Inappropriate Secretion of Antidiuretic Hormone. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1175–84. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04431007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg RB, Bersohn I, Kew MC. Hypercholesterolaemia in primary cancer of the liver. S Afr Med J. 1995;49(36):1464–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorlini M, Benini F, Cravarezza P, Romanelli G. Hypoglycemia, an atypical early sign of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(3):209–11. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldenburg WA, Van Heerden JA, Sizemore GW. Hypercalcemia and primary hepatic tumors. Arch Surg. 1982;117(10):1363–66. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380340077018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang PE, Tan CK. Paraneoplastic erythrocytosis as a primary presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63(5):202–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walcher J, Witter T, Rupprecht HD. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with paraneoplastic demyelinating polyneuropathy and PR3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(4):364–65. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arguedas MR, McGuire BM. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(12):2369–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1005690908999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinterhuber G, Drach J, Riedl E, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in association with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3):538–40. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coeytaux A, Kressig R, Zulian GB. Hepatocarcinoma with concomitant paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis. J Palliat Care. 2001;17(1):59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang SJ, Luo JC, Li CP, et al. Thrombocytosis: a paraneoplastic syndrome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(17):2472–77. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo JC, Hwang SJ, Wu JC, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer. 1999;86:799–804. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990901)86:5<799::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFadzean AJ, Todd D, Tsang KC. Polycythemia in primary carcinoma of the liver. Blood. 1958;13(5):427–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakisaka S, Watanabe M, Tateishi H, et al. Erythropoietin production in hepatocellular carcinoma cells associated with polycythemia: immunohistochemical evidence. Hepatology. 1993;18(6):1357–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tso SC, Hua ASP. Erythrocytosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: a compensatory phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 1974;28(4):497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1974.tb06668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onitilo A, Kio E, Doi SAR. Tumor-Related Hyponatremia. Clin Med Res. 2007;5(4):228–37. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabrijan T, Skreb F, Susković T. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH) produced by an adenocarcinoma of the colon, report of one case. Endocrinologie. 1985;23(3):213–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alfa-Wali M, Clark GW, Bowrey DJ. A case of gastric carcinoma and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) Surgeon. 2007;5(1):58–59. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanzaki M, Muto Y, Yoshinouchi S, et al. [A case of esophageal small cell carcinoma with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37(10):1941–44. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]