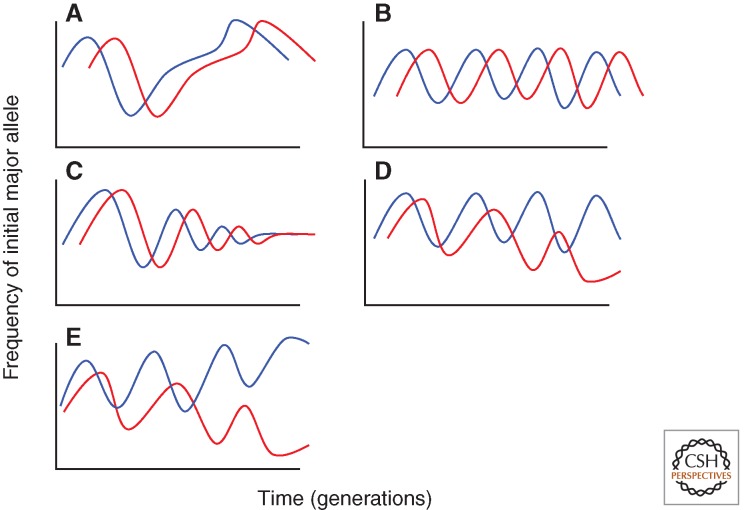

Figure 2.

The simplified dynamic outcomes of sexual conflict between SFPs and their receptors in females, based on data adapted from the predictions of Parker (1979) and Hayashi et al. (2007). In this case, sexually antagonistic coevolution is occurring between different loci in males and females, each with two alleles. The frequency of the initial most frequent allele for each of the loci in males (blue) versus females (red) is shown. (A) A continuous coevolutionary chase, in which the frequency of the female allele tracks that of the male, with no underlying pattern, through time. (B) Cyclic coevolution, in which the female allele frequency tracks that of the male, with the coevolution having a cyclical pattern through time. (C) Evolution toward an equilibrium, in which the frequency of the female allele tracks that of the male toward a stable invariant frequency. (D) Differentiation in female, but not male allele frequency (an example of Buridan’s ass). Here, the frequency of the major male allele continues to fluctuate through time, but that of the female, though initially tracking that of the male, diverges and in this case significantly decreases in frequency. Therefore, the coevolution has led to divergence in the frequencies of the two female alleles. (E) Differentiation in male and female allele frequencies. The frequency of the major male and female alleles initially show coevolutionary fluctuations; however, over time there is divergence in the frequency of both male and female alleles, with, in this case, the initial major allele in males becoming more frequent and that of the female becoming less so. Therefore, the initial coevolution has led to divergence in the frequencies of the two male and the two female alleles.