Abstract

Objective

Accurately predicting the prognosis of young patients with breast cancer (<40 years) is uncertain since the literature suggests they have a higher mortality and that age is an independent risk factor. In this cohort study we considered two prognostic tools; Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant Online (Adjuvant!), in a group of young patients, comparing their predicted prognosis with their actual survival.

Setting

North East England

Participants

Data was prospectively collected from the breast unit at a Hospital in Grimsby between January 1998 and December 2007. A cohort of 102 young patients with primary breast cancer was identified and actual survival data was recorded. The Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! scores were calculated and used to estimate 10-year survival probabilities. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to demonstrate the association between the Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! scores. A constant yearly hazard rate was assumed to generate 10-year cumulative survival curves using the Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! predictions.

Results

Actual 10-year survival for the 92 patients who underwent potentially curative surgery for invasive cancer was 77.2% (CI 68.6% to 85.8%). There was no significant difference between the actual survival and the Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! 10-year estimated survival, which was 77.3% (CI 74.4% to 80.2%) and 82.1% (CI 79.1% to 85.1%), respectively. The Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! results demonstrated strong correlation and both predicted cumulative survival curves accurately reflected the actual survival in young patients.

Conclusions

The Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! are widely used to predict survival in patients with breast cancer. In this study no statistically significant difference was shown between the predicted prognosis and actual survival of a group of young patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Young Age, Prognosis, Nottingham Prognostic Index, Adjuvant Online

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Based at a single institution leading to high level of standardisation. All patients were discussed at multidisciplinary team meeting attended to by the same team during the study period and the same team of surgeons carried out all surgery. Histopathology reporting was also constant throughout the study.

The study population in North England including the areas around Scunthorpe and Grimsby contain a very static population demographic, which likely remained very constant throughout the study period.

The Adjuvant Online (Adjuvant!) and Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) have not previously been compared in a sample of young women with breast cancer.

Long follow-up period of participants in comparison to other published studies. Our median follow-up time was 113.5 months compared with an average of 60 across other studies.

No missing data or participants lost to follow-up.

Study sample may not be representative of the entire UK population.

Relatively small sample size leading to low power, which meant a statistical difference between the NPI, Adjuvant! and actual survival was not demonstrated.

The HER2 data was not readily available for the majority of study participants. It is now used widely as guide to recommending treatment, however, it is currently not included in either the NPI or Adjuvant! calculations.

Introduction

What is my prognosis? This is the question that many patients directly or indirectly ask when given the diagnosis of breast cancer. This question is particularly difficult to answer in “younger patients” since breast cancer in young patients is often considered to be a more biologically aggressive disease with a poorer prognosis compared with older women.1–3 The definition of ‘young’ also varies between different studies with most authors identifying the upper age limit ranging from <35 years4 5 to ≤40 years.6–9

Since screening is unlikely to ever include women under the age of 40, for the purposes of this study we defined ‘young’ as patients presenting at <40 years of age. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women aged under 40. In the UK around 1300 women are diagnosed with breast cancer between the ages of 35–39 each year. The incidence of the disease in young women varies from 4% in the UK,8 10 6.2% in Italy2 and 7% in USA.6

There are two widely accepted clinical tools used to calculate an individual's prognosis, the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) and the Adjuvant Online (Adjuvant!). The NPI combines nodal status, tumour size and histological grade in a simple formula. Its advantage in prognostic discrimination has been validated by various studies and it is used widely in clinical practice.11–13 Lee and Ellis14 suggested that the NPI could be used for counselling patients with regard to their prognosis but this has not been validated specifically in younger patients.

Adjuvant! (http://www.adjuvantonline.com) is a web-based risk-assessment programme that was developed in a population from North America. The software uses similar factors to the NPI but also includes; patient age, hormone receptor status and comorbidity level.15 These variables are used to calculate the patients estimated 10-year survival probabilities, risk of relapse and the expected benefit of adjuvant therapy. A large population-based study of Canadian women of all ages with early breast cancer has validated the Adjuvant! model.16

The objective of this study was to initially identify the actual survival data for a cohort of young patients with breast cancer treated in the UK. These results were then compared with the calculated survival as assessed by both the NPI and Adjuvant! This enabled evaluation of the predictive power and accuracy of these prognostic tools in young patients with breast cancer.

Materials and methods

This is a single-centre study, which prospectively collected information over 10 years from January 1998 to December 2007. The database included all patients with primary breast cancer diagnosed and treated in the Grimsby Breast Unit from 1998 to 2002 and the South Bank Breast Unit, which was the amalgamated service of the breast clinics in Grimsby and Scunthorpe increasing the population base from 200 000 to 420 000 people in 2003–2007.

Patients

There was a cohort of 102 patients with primary breast cancer who were less than 40 years of age at the time of presentation. This equaled 5% of all breast cancers treated during the 10-year study period in this unit. Patients were excluded from the study if they were diagnosed with ‘pure’ ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; n=5) or if they had metastasis at presentation (n=5). There were 92 women with invasive disease and who had undergone potentially curative surgery in this study. Their age range was 26–39 years. Overall survival was defined as the time between first diagnosis of cancer and death from any cause, regardless of recurrence events. Patients who had neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not excluded because there is evidence that the NPI retains its prognostic value after this form of treatment.17

The case records of all patients were surveyed and the following details recorded: age at presentation, tumour size as measured at histology, tumour grade, estrogen receptor (ER) status and the number of positive lymph nodes. These factors were then used to calculate both an NPI score and the 10-year survival probability using Adjuvant! To use the Adjuvant! tool it is necessary to input other factors including the patient's comorbidity level, ER status and age. All the patients in this study were fit, so comorbidities defined as ‘average for age.’ ER positivity was determined using the Allred score. At the time of study, if the Allred score was greater than three, the oncologists would offer antihormone treatment.

Actual survival data was recorded using the continuously updated hospital electronic records system. These figures were documented at the end of 2014, which allowed a follow-up period of between 7 and 17 years. No individuals were lost during the follow-up period, which meant all 92 women contributed to the overall survival.

Treatment

All women involved in the study received treatment for breast cancer with what was considered the best practice and in accordance with network and national guidelines at the time of diagnosis. Surgery involved either breast conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy or a simple mastectomy with or without immediate reconstruction. Only six patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy following multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion. The main treatment differences over the study period of 1998–2007 was the increasing use of chemotherapy in grade 2 and 3 cancers, in patients with positive lymph node disease regardless of tumour grade and the use of herceptin in HER2 positive patients. Patients who were ER positive were offered tamoxifen since all were premenopausal although almost half the patients subsequently had a prophylactic oophorectomy and were converted to an aromatase inhibitor. All patients were assessed at an MDT and further surgery was undertaken if any of the surgical margins were incomplete, defined as a radial margin of less than 2 mm as per network guidelines.

Prognostic tools

The calculation for the NPI is (0.2×tumour size in cm)+lymph node stage (1–3)+tumour grade. There were no tumours larger than 5 cm recorded in this current study, therefore the range of NPI was 2.04–6.99. The NPI scores correspond to five groups ranging from a poor to excellent prognostic group. The numbers presented in table 1 are those reported by Blamey et al.18 For all NPI scores within each group only a single summary 10-year survival figure is reported which has been validated by previous studies. Adjuvant! data is continuous, on a scale from 0% to 100%. The mean of the Adjuvant! and NPI scores were then compared. The groupings in table 1 were used to predict the 10-year survival for each of the women in the cohort and then those predicted survival times were averaged to calculate the mean NPI score.

Table 1.

Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) details with equivalent 10-year survival figures18

| NPI group | NPI score | 10-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent prognostic group (EPG) | ≤2.40 | 96 |

| Good prognostic group (GPG) | 2.41–3.40 | 93 |

| Moderate prognostic group 1 (M1PG) | 3.41–4.40 | 81 |

| Moderate prognostic group 2 (M2PG) | 4.41–5.40 | 74 |

| Poor prognostic group (PPG) | 5.41–6.40 | 55 |

Statistical analysis

To study the correlation between the actual NPI values and Adjuvant! 10-year expected survival each individual's predicted survival was plotted and Pearson's correlation coefficient used to analyse the similarity between these two prognostic indices. The observation time was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis and an event, which was defined as death from any cause. No patients were lost to follow-up and those alive at the end of the study period (September 2014) were censored. The overall 10-year survival curve for the group was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Predicted 10-year cumulative survival curves were calculated using the NPI and Adjuvant! scores, this was achieved by assuming a constant yearly hazard rate. These graphs were then directly compared with the actual cumulative survival for the entire group of women. All analysis was carried out in SPSS statistics 22 and probability values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The average age of the 92 women involved in this study was 36.27 years. The median follow-up time was 113.5 months (range 11–120 months) and at the end of follow-up 71 (77.2%) patients were alive. The median follow-up time for those patients who died was 40 months and for those who were alive at the end of follow-up it was 120 months. The main clinically measurable parameters are shown in table 2. Over 90% of young women presented with a breast lump and the mean tumour size was 2.07 cm (SD±0.92).

Table 2.

The main pathological, clinical and treatment parameters within the study population of 92 young patients with invasive breast cancer

| All patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | N=92 | Per cent |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| ≤35 | 25 | 27.2 |

| 36–39 | 67 | 72.8 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Lump | 84 | 91.3 |

| Deformity of breast shape/skin puckering | 5 | 5.4 |

| Nipple inversion/blood discharge | 1 | 1.1 |

| Inflammation | 1 | 1.1 |

| Incidental imaging finding | 1 | 1.1 |

| Tumour size (cm) | ||

| 0.1–1.0 | 11 | 12.0 |

| 1.1–2.0 | 41 | 44.6 |

| 2.1–3.0 | 28 | 30.4 |

| 3.1–5.0 | 12 | 13.0 |

| Lymph node status | ||

| 0 | 53 | 57.6 |

| 1–3 | 25 | 27.2 |

| >3 | 14 | 15.2 |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Grade I | 16 | 17.4 |

| Grade II | 25 | 27.2 |

| Grade III | 51 | 55.4 |

| Histology | ||

| Ductal | 88 | 95.7 |

| Lobular | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 4 | 4.3 |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||

| Positive | 73 | 79.3 |

| Negative | 19 | 20.7 |

| HER2 receptor status | ||

| Positive | 6 | 6.5 |

| Negative | 33 | 35.9 |

| Unknown | 53 | 57.6 |

| Vascular invasion | ||

| Present | 40 | 43.5 |

| Not present | 52 | 56.5 |

| Surgery | ||

| Overall mastectomy rate | 46 | 50.0 |

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 20 | 21.7 |

| Mastectomy and immediate reconstruction | 26 | 28.3 |

| Breast conserving surgery | 46 | 50.0 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 6 | 6.5 |

| No | 86 | 93.5 |

| NPI | ||

| Excellent | 12 | 13.0 |

| Good | 14 | 15.2 |

| Moderate 1 | 25 | 27.2 |

| Moderate 2 | 20 | 21.7 |

| Poor | 21 | 22.8 |

NPI, Nottingham Prognostic Index.

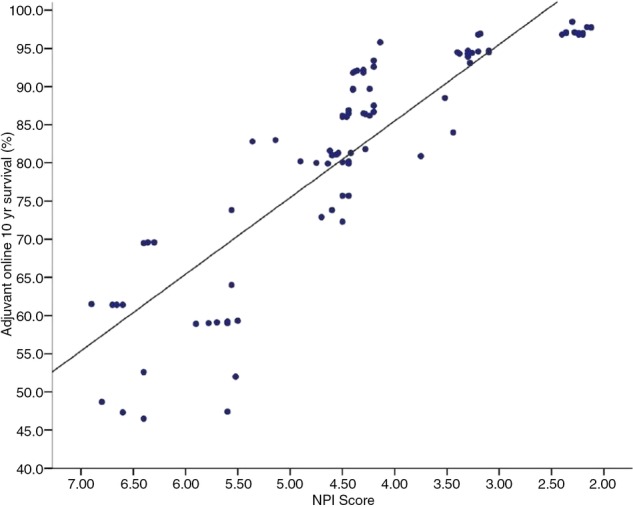

Directly comparing the actual survival with both NPI and Adjuvant! 10-year survival prognosis, confirms that there is a strong linear correlation between these two clinical tools (figure 1). This is further demonstrated by Pearson's correlation coefficient, which was 0.873 (CI 0.835 to 0.901).

Figure 1.

The 10-year survival probability at the time of diagnosis for individual young women aged <40 years between 1998 and 2007. The distribution of survival figures calculated using the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) compared with those calculated using the Adjuvant! model.

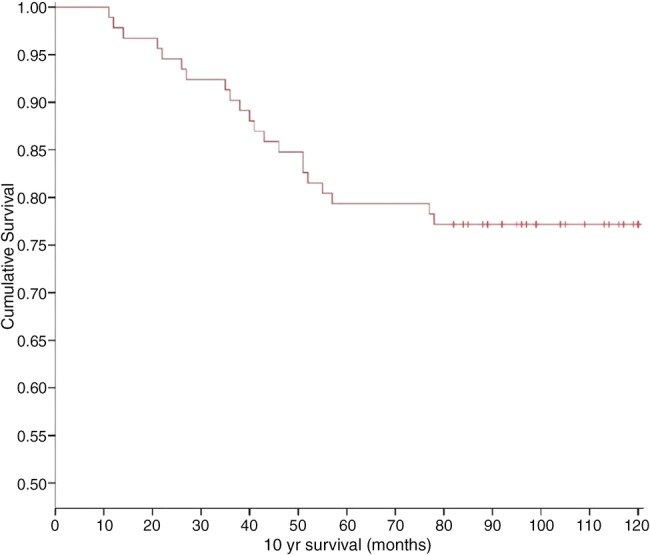

Kaplan-Meier actual survival analysis of young women, diagnosed with breast cancer in this study revealed that the 5-year and 10-year survival rates were 79.3% (CI 71.1% to 87.5%) and 77.2% (CI 68.6% to 85.8%), respectively. The Kaplan-Meier survival plot in figure 2 indicates that patients, who survived the first 5 years after diagnosis, had a high probability of surviving to 10 years.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival for 92 young women diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer that underwent potentially curative surgery (crosses represent censored cases).

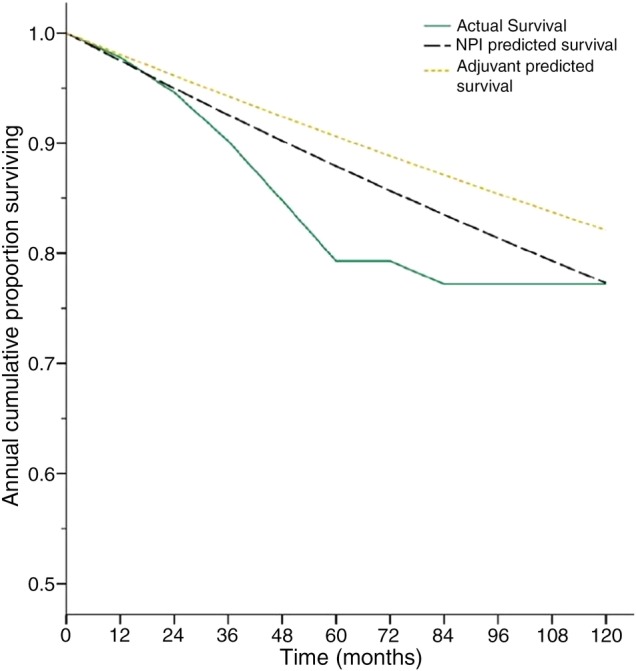

Figure 3 illustrates the overall 10-year survival rate for the study population and compares it to the NPI and Adjuvant! predicted survival rates. The NPI predicted survival shows a stronger resemblance to the actual survival curve. A higher survival rate was recorded using the Adjuvant! scores. However, there was no statistically significant difference between survival figures generated by the prognostic tools and the actual survival (table 3).

Figure 3.

The actual survival curve for the group demonstrating the percentage survival after each year over a 10-year follow-up period. The predicted curves generated from the individual Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) and Adjuvant! scores are shown for comparison.

Table 3.

Overall survival of young patients after 10-years of follow-up determined using the Kaplan-Meier method

| 10-year survival (%) | |

|---|---|

| Overall survival | 77.2 (CI 68.6 to 85.8) |

| NPI prediction | 77.3 (CI 74.4 to 80.2) |

| Adjuvant! prediction | 82.1 (CI 79.1 to 85.1) |

This figure is compared with the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) and Adjuvant! 10-year predicted survival at the time of diagnosis. The predictions are equivalent to the mean values calculated from the prognostic scores for each individual.

Discussion

In the literature young patients with breast cancer are usually said to have a poor prognosis.7–9 This is often attributed to their higher incidence of grade 3 tumours, more lymph node involvement and less oestrogen positive tumours. These results are usually compared with older patient groups defined as >50 or >60 years.2 5 7 There is ongoing controversy as to whether age is a risk factor independent of the above biological factors.1 3 5 McAree et al8 found in a series of 57 young patients with breast cancer that nearly 16% of their patients fulfilled the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for genetic testing but only 1.8% actually carried the gene.

The aim of this study was to assess the mortality in young patients (<40 years of age at presentation) during a 10-year follow-up period then compare the figures with the NPI and Adjuvant! in order to assess their accuracy at predicting survival in young patients. Over the past few years, both the NPI and Adjuvant! have been accepted as accurate predictors of survival in older patients and a guide to choice of treatment but their value in young patients is either not established or disputed.19

While our series is modest, it is similar in size to other studies reflecting the limited experience worldwide in young patients with breast cancer, but unlike other studies our data is complete with no patients lost to follow-up. Our study population has similar tumour size, incidence of grade 3 cancers, ER and lymph node involvement to the literature and our overall survival results are also similar as demonstrated in table 4. This illustrates that similar results have been recorded in studies in the UK,8 20 Sweden,5 7 9 Australia3 21 and Italy.2

Table 4.

Comparing the data and results from eight similar studies that have investigated invasive breast cancer within a population of young women

| Patient numbers | Average tumour size (mm) | Grade 3 tumours (%) | Lymph node involved (%) | Estrogen receptor negative (%) | HER2 receptor positive (%) | Overall survival at 5 years (%) | Overall survival at 10 years (%) | Median follow-up (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McAree et al8 | 57 | 21.3 | 40.7 | 40.0 | 23.8 | 30.0 | 77.0 | – | 52.7 |

| Karihtala et al9 | 269 | – | 46.0 | 52.4 | 33.5 | 15.2 | 80.0 | 71.0 | 74.0 |

| Jayasinghe et al3 | 47 | – | 31.9 | 53.2 | – | – | 60.0 | 49.0 | – |

| Sidoni et al2 | 50 | 22.8 | 38.0 | 53.0 | 46.0 | 48.0 | – | – | – |

| Gillett et al21 | 58 | 23.0 | 40.0 | 34.0 | – | – | 90.0* | – | 31.0 |

| Sundquist et al7 | 107 | – | 64.0 | 37.0 | – | – | 72.0 | 58–63† | 134.0 |

| Fredholm et al5 | 1329 | – | 21.0‡ | 46.0 | 26.0‡ | – | 83.8 | – | – |

| Copson et al20 | 2956 | 22.0 | 58.9 | 50.6 | 33.7 | 24.3 | 81.9 | – | 60 |

| Current study | 92 | 20.1 | 55.4 | 42.5 | 20.7§ | 6.5 | 79.3 | 77.2 | 113.5 |

*Sixteen per cent of patients were pure ductal carcinoma in situ.

†Two figures recorded depending on study period.

‡Data missing for the tumour grade in 60% and estrogen receptor status in 18% of patients.

§Estrogen receptor positive if Allred score was greater than 3/8.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is now widely used and recognised as a treatment modality for locally invasive breast cancer especially in young patients. The Prospective Study of Outcomes in Sporadic versus Hereditary Breast Cancer (POSH) reports between 2000 and 2008 15.6% of young women had neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with 6.5% in the current study which demonstrates the increased acceptance of this form of treatment over the past decade.20

The data in this study was prospectively collected at the weekly MDT meeting. All histology was first reported by a member of a dedicated group of histopathologists, one of whom was also the unit's MDT dedicated breast histopathologist. This ensured the histopathology was accurate and the data complete. In particular there was consensus reporting of the tumour grade, which is a very important component in both the NPI and Adjuvant! calculations. A further strength of the present study is that this population is relatively static. Unfortunately the HER2 was not readily available for much of the study. Although it is now used widely as guide to recommending treatment, it is currently not included in either the NPI or Adjuvant! calculations. To add this parameter would need at least a revalidation of the NPI calculation.14

Adjuvant! was developed in the USA using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) tumour registry.15 The biological variables; tumour size, grade and lymph node involvement are included in the Adjuvant! calculation with additional inclusions of the patients’ general fitness and the oestrogen status. The score weighting given for each of these factors is not known when applied in the Adjuvant! computer calculation. In a Canadian study to validate the Adjuvant! the authors found the 10-year predicted and overall outcomes were within 1% for overall survival, however Adjuvant! overestimated overall survival in patients under 35 years old by 8.6%.16 The Adjuvant! has also been validated by a Dutch study which found that it accurately predicted 10-year outcomes in their population overall but it was less reliable in the subset of young patients. Currently a correction factor of 1.5 is applied to the score for ER-positive patients under 35 years. Despite this Mook et al19 concluded that the correction was insufficient and an additional correction was required for patients between 35 and 40 years with ER-positive tumours. A British study in Oxford reported a statistically significant difference of 5.54% in predicted and observed overall survival using the Adjuvant! but made no specific reference to young patients.22

In the current study, the NPI and Adjuvant! predicted similar survival outcomes for young patients with breast cancer with direct linear correlation (p<0.01). The large variability between the NPI and Adjuvant! 10-year survival rates within the ‘poor’ NPI group (figure 1) were insignificant. It is suggested that this variability is caused by the heterogeneity of the group with between 1 and 22 lymph nodes involved and some patients likely having already developed micrometastasis. Neither prognostic tool is designed to predict metastasis at presentation.

The NPI appears to maintain its accuracy in young women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. One of the many benefits of the NPI tool is its simplicity and the fact no computer is needed to perform the calculation. Other studies have validated the accuracy of the NPI within young populations with breast cancer by showing that the mortality rate is no different from what would be expected according to the NPI.11

The present study showed no statistical difference between the accuracy of the NPI or Adjuvant! However, the impression that the current Adjuvant! appears to overestimate the prognosis by 5% has been identified by other studies in the Netherlands and Canada.16 19 The accuracy of the Adjuvant! appears to be population specific as a recent study in Ireland demonstrated that the Adjuvant! actually underestimated the overall 10-year survival of a cohort of 77 women.23 These variations have been suggested to correlate with changes in ethnicity and age distribution in populations outside the USA where the Adjuvant! was developed.

The main limitation of this study was the sample size was too small to demonstrate a statistically significant difference between the prognostic tools and the actual survival. If the Adjuvant! over prediction is a true result then a larger study will need to be performed to investigate this. A retrospective calculation using 77.2% as the true survival rate indicates that reducing the width of the 95% CI to 10% would require a sample of 273 patients. This figure for the 95% CI would exclude the Adjuvant! predicted value of 82.1%. The results emphasise the need for a national study to further scrutinise the accuracy of the Adjuvant! and NPI in young women with breast cancer.

The survival data from studies that have specifically investigated young patients with breast cancer is shown in table 4. The overall impression is that few papers in the literature have explored the value of the NPI or Adjuvant! in this group of patient. The current data should be interpreted as an establishment of information on this topic in a UK population. In one study of 107 patients the analysis demonstrated that if the NPI was between 3.4 and 5.39 the mortality rate was only 24% during the 10-year study period. Concluding, that the NPI was a valuable tool when counselling young patients with breast cancer in agreement with the current results.7

Conclusions

This study looked at the mortality of young patients with breast cancer (<40 years old) treated in a single breast unit with an average follow-up of 9.5 years. The results revealed that the 5-year and 10-year survival was 79.3% and 77.2%, respectively between 1998 and 2007. The NPI seemed to be more accurate whereas Adjuvant! overpredicted survival by around 5% although the study had insufficient power to statistically define the difference. This study provides a platform from which future research can further investigate the results highlighted here and whether these findings are reproducible across the UK. The NPI and Adjuvant! appear to be precise methods for predicting 10-year survival in young women with breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BJH was responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Diana Princess of Wales Hospital Ethical Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Maggard MA, O'Connell JB, Lane KE et al. . Do young breast cancer patients have worse outcomes? J Surg Res 2003;113:109–13. 10.1016/S0022-4804(03)00179-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidoni A, Cavaliere A, Bellezza G et al. . Breast cancer in young women: clinicopathological features and biological specificity. Breast 2003;12:247–50. 10.1016/S0960-9776(03)00095-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayasinghe UW, Taylor R, Boyages J. Is age at diagnosis an independent prognostic factor for survival following breast cancer? ANZ J Surg 2005;75:762–7. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jmor S, Al-Sayer H, Heys SD et al. . Breast cancer in women aged 35 and under: prognosis and survival. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2002;47:693–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredholm H, Eaker S, Frisell J et al. . Breast cancer in young women: poor survival despite intensive treatment. PLoS One 2009;4:e7695 10.1371/journal.pone.0007695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankey BF, Miller B, Curtis R et al. . Trends in breast cancer in younger women in contrast to older women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs 1994;16:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundquist M, Thorstenson S, Brudin L et al. . Incidence and prognosis in early onset breast cancer. Breast 2002;11:30–5. 10.1054/brst.2001.0358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAree B, O'Donnell ME, Spence A et al. . Breast cancer in women under 40years of age: a series of 57 cases from Northern Ireland. Breast 2010;19:97–104. 10.1016/j.breast.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karihtala P, Winqvist R, Bloigu R et al. . Long-term observational follow-up study of breast cancer diagnosed in women ≤40 years old. Breast 2010;19:456–61. 10.1016/j.breast.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Research UK. Breast cancer incidence statistics. Cancer Research UK, 2014. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/breast/incidence/uk-breast-cancer-incidence-statistics (accessed 30 Oct 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundquist M, Thorstenson S, Brudin L et al. . Applying the Nottingham Prognostic Index to a Swedish breast cancer population. South East Swedish Breast Cancer Study Group. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999;53:1–8. 10.1023/A:1006052115874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Eredita G, Giardina C, Martellotta M et al. . Prognostic factors in breast cancer: the predictive value of the Nottingham Prognostic Index in patients with a long-term follow-up that were treated in a single institution. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:591–6. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00435-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albergaria A, Ricardo S, Milanezi F et al. . Nottingham Prognostic Index in triple-negative breast cancer: a reliable prognostic tool? BMC Cancer 2011;11:299 10.1186/1471-2407-11-299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AHS, Ellis IO. The Nottingham prognostic index for invasive carcinoma of the breast. Pathol Oncol Res 2008;14:113–15. 10.1007/s12253-008-9067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravdin PM, Siminoff LA, Davis GJ et al. . Computer program to assist in making decisions about adjuvant therapy for women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivotto IA, Bajdik CD, Ravdin PM et al. . Population-based validation of the prognostic model ADJUVANT! for early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2716–25. 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chollet P, Amat S, Belembaogo E et al. . Is Nottingham prognostic index useful after induction chemotherapy in operable breast cancer? Br J Cancer 2003;89:1185–91. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blamey RW, Ellis IO, Pinder SE et al. . Survival of invasive breast cancer according to the Nottingham Prognostic Index in cases diagnosed in 1990–1999. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:1548–55. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mook S, Schmidt MK, Rutgers EJ et al. . Calibration and discriminatory accuracy of prognosis calculation for breast cancer with the online Adjuvant! program: a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1070–6. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70254-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copson E, Eccles B, Maishman T et al. . Prospective observational study of breast cancer treatment outcomes for UK women aged 18–40years at diagnosis: the POSH study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:978–88. 10.1093/jnci/djt134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillett D, Kennedy C, Carmalt H. Breast cancer in young women. Aust N Z J Surg 1997;67:761–4. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb04575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell HE, Taylor MA, Harris AL et al. . An investigation into the performance of the Adjuvant! Online prognostic programme in early breast cancer for a cohort of patients in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer 2009;101:1074–84. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quintyne KI, Woulfe B, Coffey JC et al. . Correlation between Nottingham Prognostic Index and Adjuvant! Online prognostic tools in patients with early-stage breast cancer in Mid-Western Ireland. Clin Breast Cancer 2013;13:233–8. 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.