Background: Calcium-independent PLA2γ (iPLA2γ) is a membrane-bound enzyme that localizes at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

Results: iPLA2γ amplified activation of the ATF6 pathway of the unfolded protein response, resulting in up-regulation of ER chaperones and cytoprotection.

Conclusion: iPLA2γ enhances activation of ATF6.

Significance: Modulating iPLA2γ activity may provide opportunities for pharmacological intervention in glomerular diseases associated with ER stress.

Keywords: Cell Death, Cell Signaling, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress (ER Stress), Phospholipase A, Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)

Abstract

Injury of visceral glomerular epithelial cells (GECs) causes proteinuria in many glomerular diseases. We reported previously that calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ (iPLA2γ) is cytoprotective against complement-mediated GEC injury. Because iPLA2γ is localized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), this study addressed whether the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ involves the ER stress unfolded protein response (UPR). In cultured rat GECs, overexpression of the full-length iPLA2γ, but not a mutant iPLA2γ that fails to associate with the ER, augmented tunicamycin-induced activation of activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) and induction of the ER chaperones, glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94) and glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78). Augmented responses were inhibited by the iPLA2γ inhibitor, (R)-bromoenol lactone, but not by the cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin. Tunicamycin-induced cytotoxicity was reduced in GECs expressing iPLA2γ, and the cytoprotection was reversed by dominant-negative ATF6. GECs from iPLA2γ knock-out mice showed blunted ATF6 activation and chaperone up-regulation in response to tunicamycin. Unlike ATF6, the two other UPR pathways, i.e. inositol-requiring enzyme 1α and protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase pathways, were not affected by iPLA2γ. Thus, in GECs, iPLA2γ amplified activation of the ATF6 pathway of the UPR, resulting in up-regulation of ER chaperones and cytoprotection. These effects were dependent on iPLA2γ catalytic activity and association with the ER but not on prostanoids. Modulating iPLA2γ activity may provide opportunities for pharmacological intervention in glomerular diseases associated with ER stress.

Introduction

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2)3 comprises a family of enzymes that play important roles in numerous cellular processes. PLA2s hydrolyze the acyl bond at the sn-2 position of phospholipids to yield free fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids (1, 2). Both products represent precursors for signaling molecules that can exert multiple biological functions, in particular, arachidonic acid can be converted into bioactive eicosanoids by cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochrome P450 proteins (3). Calcium-independent PLA2γ (iPLA2γ) is a membrane-bound enzyme that is reported to localize at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), peroxisomes, and mitochondria (4). These distinct sites of localization are likely dependent on specific domains in the N terminus of the enzyme (5). In renal proximal tubular cells, iPLA2γ removes oxidized phospholipids from the ER membrane during oxidative stress; thus, iPLA2γ may act to repair damaged lipids or prevent lipid peroxidation during oxidative stress (4). Consistent with these results, iPLA2γ knockdown in renal cells increased lipid peroxidation and induced apoptosis (6). Conversely, inhibition of microsomal iPLA2γ in rabbit renal proximal tubular cells during cisplatin-induced apoptosis reduced apoptosis markers, indicating that iPLA2γ contributes to apoptosis (7). Mitochondrial iPLA2γ has been also shown to actively participate in the permeability transition pore opening of the mitochondria and the release of the proapoptotic cytochrome c (8). iPLA2γ knock-out mice demonstrate multiple bioenergetic dysfunctional phenotypes (9), although they are resistant to obesity and show less insulin resistance (10). Thus, the biological functions of iPLA2γ in the context of cell injury are complex and appear to be cell/context-dependent.

Glomerular visceral epithelial cells (GECs) or podocytes are intrinsic components of the kidney glomerulus and play a key role in the maintenance of glomerular permselectivity. Various forms of glomerulonephritis are associated with podocyte injury, which leads to impaired glomerular permselectivity (proteinuria). We reported previously that complement C5b-9 activates iPLA2γ in GECs in a protein kinase-dependent manner (11) and that overexpression of iPLA2γ is protective against complement-dependent GEC injury (12). In GECs, iPLA2γ is localized at the ER and mitochondria, and this localization is dependent on the N-terminal region of iPLA2γ (11). The isoform of iPLA2γ that lacks the N-terminal region is misplaced from the ER and fails to produce prostaglandin E2 in response to complement, although its activity is similar to the full-length isoform when tested in vitro. Thus, it appears that one of the major sites of iPLA2γ activation in GECs is the ER; however, physiological functions of iPLA2γ at the ER have not been well delineated.

In the ER, proteins are properly folded and are then transported to the Golgi apparatus, whereas misfolded proteins undergo ER-associated degradation (13). When the amount of misfolded proteins in the ER exceeds the capacity of the folding apparatus and ER-associated degradation machinery, the misfolded proteins lead to ER stress and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (14–17). There are three major UPR pathways, namely activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) pathways (14, 16, 18). Accumulation of misfolded proteins leads to release of ATF6 from the ER and translocation to the Golgi, where it is cleaved by the site-1 and site-2 proteases. The cleaved cytosolic fragment of ATF6, which has a DNA-binding domain, migrates to the nucleus to activate transcription of ER chaperones, including glucose-regulated protein 94 (GRP94) and glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), which in turn enhance ER protein folding capacity and limit cytotoxicity. The IRE1α endoribonuclease cleaves X box-binding protein-1 (xbp1) mRNA and changes the reading frame to yield a potent transcriptional activator, which works in parallel with ATF6 to activate transcription of ER chaperones genes. PERK phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor-2α subunit (eIF2α), which reduces the general rate of translation and aims at decreasing the protein load on a damaged ER. The three UPR pathways are often activated together, but selective activation of some pathways together with suppression of others can occur (16, 19).

The goal of this study was to address the mechanisms of cytoprotection by iPLA2γ in GECs. Because iPLA2γ is localized at the ER in GECs, we studied whether cytoprotection by iPLA2γ involves the UPR pathways. We demonstrate that in GECs, iPLA2γ amplifies tunicamycin-induced ATF6 activation and up-regulation of ER chaperones, which limits cell injury.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Tissue culture media and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen. Electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad. Mouse monoclonal anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and rat anti-GRP94 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-GRP78 (BiP) antibody was from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Rabbit anti-phospho-eIF2α (Ser51) was purchased from New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Rabbit monoclonal anti-actin antibody, tunicamycin, thapsigargin, and U18666A were from Sigma. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents were from GE Healthcare. (R)-Bromoenol lactone (R-BEL) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Wild type (WT), M4, and S511A/S515A GFP-iPLA2γ cDNAs were described previously (11). Plasmids 5xATF6-GL3, pCGN-ATF6(1–373)m1, and low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) promoter-luciferase were from Addgene (Cambridge, MA) (20, 21). A retroviral construct consisting of the SV40 large T antigen gene containing both the tsA58 and the U19 mutations was kindly provided by Prof. Parmjit Jat (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, London, UK) (22).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Rat GECs were derived from glomerular explants, and the methods for culture and characterization have been described previously (11, 12, 23). GECs were maintained in K1 medium on plastic substratum. Rat GECs stably transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ and control GECs were described previously (11). 293T and COS-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfection of GECs or COS-1 cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000.

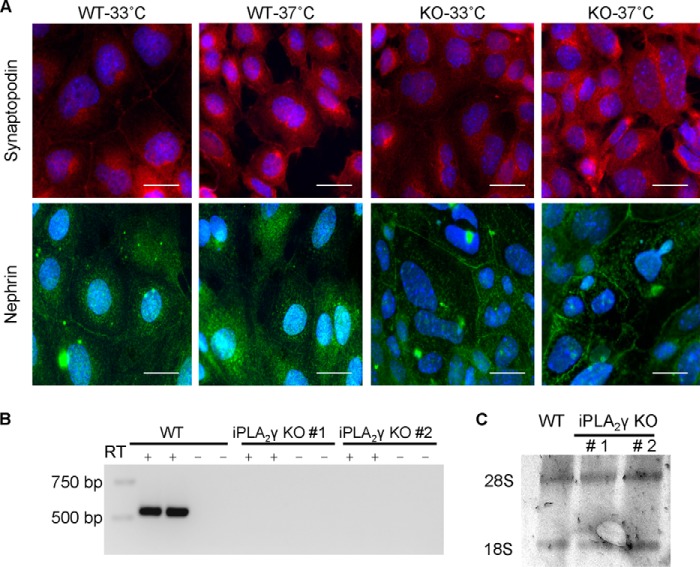

iPLA2γ knock-out (KO) mice were kindly provided by Dr. Richard Gross (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) (24). Mouse GECs were derived from iPLA2γ KO mice and WT control. Briefly, glomeruli were isolated from both KO and WT mice by differential sieving, as described previously (25). The purity of glomeruli obtained from the isolation was consistently ∼70–80%. Isolated glomeruli were seeded on type I collagen-coated culture dishes for 5 days in K1 medium (11). A week after the first epithelial cell outgrowth, the cells were immortalized by infection with retrovirus carrying the temperature-sensitive SV40 large T antigen, which was performed by adding retrovirus-containing supernatants from 293T packaging cells (22, 26). Selection was carried out with puromycin, and colonies were isolated using cloning rings. Then the cells were allowed to grow for 2 additional weeks under permissive conditions (33 °C). More than 98% of cells showed morphological characteristics of GECs. By immunofluorescence microscopy (method below), both cell lines displayed positive staining for synaptopodin and nephrin at both permissive (33 °C) and nonpermissive (37 °C) temperatures (Fig. 1A). These results confirm that the cells are of podocyte origin, although they are distinct from certain other GEC lines, where expression of synaptopodin was reported only at the nonpermissive temperature (25, 27).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of iPLA2γ KO mouse GECs. A, immunofluorescence staining for podocyte-specific proteins. GECs were cultured on glass coverslips for 24 h and were then stained for synaptopodin and nephrin. WT and iPLA2γ KO GECs displayed positive staining for synaptopodin at the permissive temperature (33 °C). The staining appeared stronger at the nonpermissive temperature (37 °C), particularly in the cytoplasm and extending into cell processes. Expression of nephrin was visualized as a punctate cell surface and cytoplasmic staining. Nephrin was expressed at both permissive (33 °C) and nonpermissive (37 °C) temperatures in both cell lines. Bars, 20 μm. B, expression of endogenous iPLA2γ mRNA in mouse GECs was assessed by RT-PCR. WT mouse GECs express iPLA2γ mRNA. iPLA2γ KO #1 and KO #2 cell lines (two different clones of mouse GECs), do not show any iPLA2γ mRNA. Control lanes (−) were devoid of RT. C, 28 S and 18 S ribosomal RNAs were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide and demonstrate equal loading.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; method below) confirmed the absence of iPLA2γ mRNA expression in cells from KO mice (Fig. 1, B and C). In addition, quantitative RT-PCR (see below) was performed to measure expression of iPLA2γ mRNA isoforms in cultured GEC lines (Table 1). We were not able to compare the level of iPLA2γ protein expression, because we could not identify an antibody that reacts with endogenous iPLA2γ protein reliably.

TABLE 1.

Expression of iPLA2γ mRNAs in GEC lines

Total RNA was extracted from GECs (and mouse glomeruli for comparison). RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified using quantitative PCR. In the GECs transfected with full-length (M1) GFP-iPLA2γ WT or M4 GFP-iPLA2γ, RNA was extracted 24 h after transfection. Relative quantification (RQ) is presented as an average of 3–6 values.

| Cell type | RQ |

|---|---|

| Untransfected rat GECs | 1.0 |

| M1 GFP-iPLA2γ WT-rat GECs | 17.9 |

| M4 GFP-iPLA2γ-rat GECs | 16.8 |

| WT mouse GECs | 0.5 |

| iPLA2γ KO mouse GECs | 0 |

| WT mouse glomeruli | 1.6 |

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were cultured on glass coverslips for 24 h. All incubations were carried out at 22 °C. To examine the expression of nephrin and synaptopodin, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-nephrin antiserum, rabbit anti-synaptopodin antibody, or nonimmune rabbit serum (negative control) diluted in 3% BSA for 2 h. Cells were washed and incubated with fluoresceinated goat anti-rabbit IgG in 3% BSA for 30 min. Nuclei were counter-stained with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 30 nm) in PBS for 4–5 min just before mounting the coverslips onto glass slides. Staining was visualized with a Zeiss AxioObserver fluorescence microscope with visual output connected to an AxioCam digital camera.

RT-PCR

For the analysis of iPLA2γ mRNA expression, total RNA was extracted from iPLA2γ KO and WT immortalized mouse GECs using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed by QuantiTect reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The RT step was omitted in negative controls. PCR for iPLA2γ was done using mouse iPLA2γ sequence-specific primers as follows: forward 5′-ATTGATGGTGGAGGAACAAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-ATGGCCTGCCACATTTTATAC-3′. PCR consisted of 23 cycles (95 °C for 30 s; 62 °C for 30 s; and 72 °C for 105 s (but 10 min in the final cycle)) and was carried out with Taq DNA polymerase. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels after staining with ethidium bromide.

For analysis of xbp1 mRNA splicing, total RNA was extracted from GECs and reverse-transcribed as above. To amplify xbp1 mRNA, the primers uses were as follows: forward 5′-AACTCCAGCTAGAAAATCAGC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCATGGGAAGATGTTCTGGG-3′. PCR consisted of 25 cycles (95 °C for 30 s; 58 °C for 30 s; and 72 °C for 1 min (but 10 min in the final cycle)) and was carried out with Taq DNA polymerase. xbp1 products were visualized on agarose gels, as 530- and 556-bp fragments representing spliced (xbp1S) and unspliced (xbp1U) xbp1.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from GECs and glomeruli using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and was reverse-transcribed as above. The PCR for iPLA2γ was done using rat, mouse, and human iPLA2γ sequence-specific primers as follows: forward 5′-CCTGAAGGAAAAGGAGTGG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTGTTCCTCCACCATCAAT-3′. Real time PCRs were performed on an ABI 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and amplified DNA was detected by SYBR Green incorporation. Values were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels in the same sample.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

Cells were transiently transfected with empty vector or iPLA2γ, together with a firefly luciferase reporter cDNA and a cDNA-encoding Renilla luciferase, using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were cultured for 24 h and then stimulated with tunicamycin (0.1 μg/ml, 18 h). Lysates were assayed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using a kit (Dual-LuciferaseTM reporter assay system, Promega, Madison, WI), according to manufacturer's instructions. Measurements were performed in a Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN), and the ratios between firefly and Renilla luciferase activities (the latter a marker of transfection efficiency) were calculated. Results are presented in relative luminescence units.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 125 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EGTA, 2 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mm NaF, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics). Equal amounts of lysate proteins were dissolved in Laemmli buffer and were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were then electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked at room temperature for 1 h with 5% dry milk in buffer containing 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm EDTA, and 0.05% Tween 20. The membrane was then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies and developed with ECL.

Assay for Tunicamycin-induced Cell Death

Tunicamycin-induced cell death was determined by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, as described previously (28). Briefly, cells were cultured in a 24-well plate for 48 h. DNA transfection (when required) was performed 24 h after plating. Cells were then treated with 1–10 μg/ml tunicamycin for 24 h. At the end of the incubation, cell supernatants were collected, and the cells adherent to the culture dishes were lysed with 1% Triton X-100. Then both cell supernatants and Triton lysates were analyzed for LDH activity by adding NAD in glycine/lactate buffer. LDH converts lactate and NAD to pyruvate and NADH. The rate of increase in the absorbance at 340 nm, due to formation of NADH, represents LDH activity. Specific release of LDH release was calculated as supernatant/(supernatant + lysate) × 100.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± S.E. One-way analysis of variance was used to determine significant differences among groups. When significant differences were found, individual comparisons were made between groups using the Student's t test and adjusting the critical value according to Bonferroni's method.

RESULTS

iPLA2γ Amplifies the Activation of ATF6

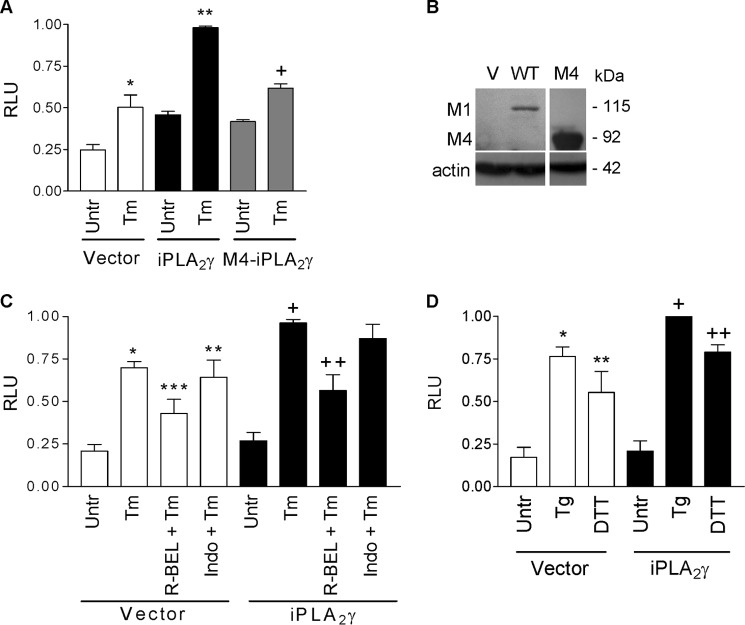

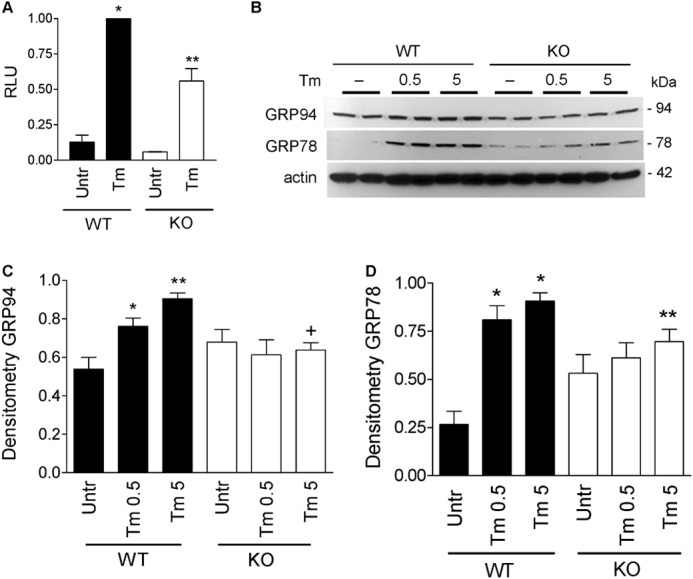

Previous studies demonstrated that complement activates iPLA2γ and that the iPLA2γ pathway restricts complement-induced cytotoxicity in GECs (11, 12). Given that iPLA2γ is, in part, localized at the ER, we hypothesized that the cytoprotective actions of iPLA2γ may involve the UPR. First, we addressed the activation of ATF6, by employing a reporter construct containing five tandem copies of an ATF6-response element fused to firefly luciferase (p5xATF6-GL3) (20). GECs were co-transfected with full-length (M1) GFP-iPLA2γ (or empty vector in control) and the ATF6 luciferase reporter. (In a previous study, we showed that the enzymatic activity of GFP-iPLA2γ was comparable with untagged iPLA2γ (11).) Cells were then treated for 18 h with the N-linked glycosylation inhibitor, tunicamycin, which causes accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER and is a potent inducer of ER stress (15). In vector-transfected control cells, tunicamycin stimulated ATF6 reporter activity, and this was augmented significantly by iPLA2γ (Fig. 2A). In contrast, an N-terminally truncated form of iPLA2γ (M4 iPLA2γ), which does not associate with the ER (11), failed to augment tunicamycin-induced ATF6 activation, implying that the association with the ER is required for ATF6 activation (Fig. 2A). Expression of M1 and M4 iPLA2γ was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). Both the tunicamycin-stimulated and the iPLA2γ-amplified ATF6 activities were inhibited by the iPLA2γ inhibitor, R-BEL, but not by indomethacin, an inhibitor of cyclooxygenases (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the tunicamycin-induced activation of the ATF6 reporter is dependent on endogenous and overexpressed iPLA2γ catalytic activity but not prostanoids. An analogous experiment was performed using different ER stressors, including thapsigargin, a potent inhibitor of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (29), and DTT, a reducing agent, which prevents formation of disulfide bonds between cysteine residues of proteins, thereby inducing protein misfolding and ER stress (30). Similar to tunicamycin, thapsigargin and DTT stimulated ATF6 reporter activity, and iPLA2γ amplified their effects (Fig. 2D). To substantiate the conclusion that endogenous iPLA2γ can also modulate the ATF6 pathway, we employed GECs derived from WT and iPLA2γ KO mice. The tunicamycin-induced activation of the ATF6 reporter was reduced in iPLA2γ KO GECs, compared with WT (Fig. 3A). Thus, both endogenous and ectopically overexpressed iPLA2γ contribute to the activation of the ATF6 pathway of the UPR in GECs.

FIGURE 2.

iPLA2γ amplifies tunicamycin-induced ATF6 luciferase-reporter activity. A, rat GECs were transiently co-transfected with full-length (M1) GFP-iPLA2γ, N-terminal truncated (M4) GFP-iPLA2γ, or vector (control), plus ATF6 firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase. After 24 h, cells were untreated (Untr) or incubated with tunicamycin (Tm, 0.1 μg/ml, 18 h). Tunicamycin stimulated ATF6 reporter activity (expressed in relative luminescence units (RLU)), and iPLA2γ amplified the effect of Tm. *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated (Vector); **, p < 0.001 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm) and versus M4 iPLA2γ (Tm); +, p < 0.01 Tm versus untreated (M4 iPLA2γ), three experiments performed in triplicate. B, representative anti-GFP antibody immunoblots showing expression of full-length (M1) WT and N-terminal truncated (M4) GFP-iPLA2γ (V, vector transfection). C, rat GECs were transiently co-transfected as in A. After 24 h, cells were untreated (Untr), incubated with tunicamycin (Tm, 0.1 μg/ml, 18 h), or preincubated with R-BEL (5 μm, 30 min) or indomethacin (10 μm, 30 min) before treatment with Tm. Tunicamycin stimulated ATF6-reporter activity, and iPLA2γ amplified the effect of Tm. The amplified ATF6 activity was inhibited by R-BEL but not by indomethacin. *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated (Vector); **, p < 0.01 Tm + indomethacin (Indo) versus untreated (Vector); ***, p < 0.05 R-BEL + Tm versus Tm (Vector); +, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm); ++, p < 0.001 R-BEL + Tm versus Tm (iPLA2γ), five experiments performed in triplicate. D, GECs were co-transfected as in A. Cells were untreated or incubated with thapsigargin (Tg, 0.5 μm, 18 h) or DTT (0.5 μm, 18 h). Thapsigargin and DTT stimulated ATF6 reporter activity, and iPLA2γ amplified the effect of thapsigargin and DTT. *, p < 0.001 thapsigargin versus untreated (Vector); **, p < 0.05 DTT versus untreated (Vector); +, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tg). ++, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (DTT), four experiments performed in triplicate.

FIGURE 3.

Endogenous iPLA2γ amplifies ATF6 activity and ER chaperones. A, WT and iPLA2γ KO mouse GECs were co-transfected with ATF6 firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase. Cells were untreated (Untr), or incubated with tunicamycin (Tm, 0.1 μg/ml, 18 h). Tunicamycin-induced activation of ATF6 reporter was greater in WT cells, compared with iPLA2γ KO. *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated (WT); **, p < 0.001 WT versus KO (Tm), four experiments performed in triplicate. RLU, relative luminescence units. B, WT and iPLA2γ KO mouse GECs were untreated or incubated with Tm (0.5 or 5 μg/ml for 6 h). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to GRP94, GRP78, and actin. Tunicamycin increased GRP94 and GRP78 expression levels only in WT podocytes. B, representative immunoblots; C and D, densitometric quantification. C, GRP94: *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated; +, p < 0.01 WT versus KO (Tm 5), six experiments performed in duplicate. D, GRP78: *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated; **, p < 0.05 WT versus KO (Tm 5), five experiments performed in duplicate.

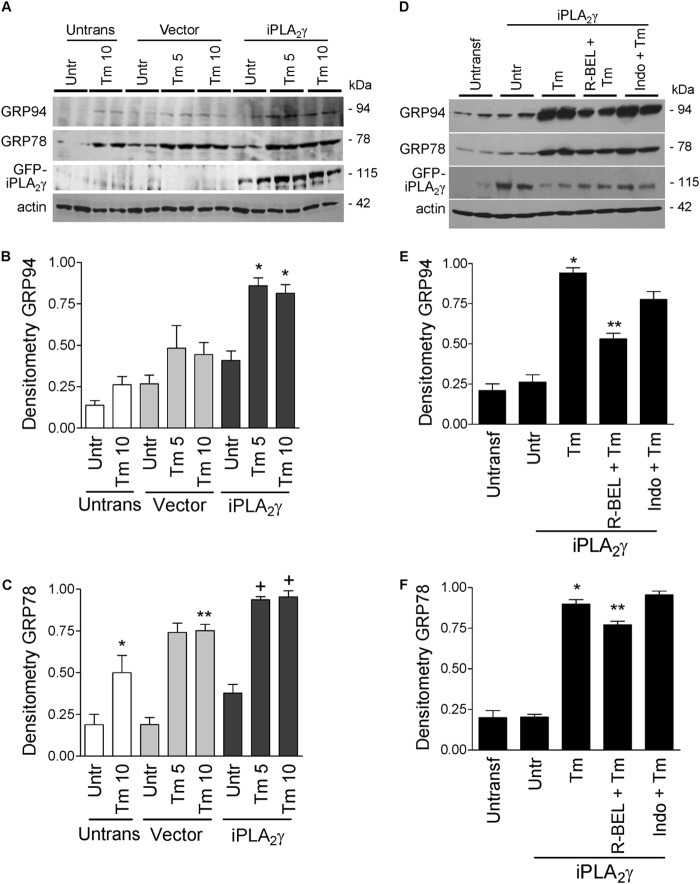

iPLA2γ Amplifies the Induction of ER Chaperones

In mammalian cells, the up-regulation of ER chaperones, including GRP94 and GRP78 (BiP), is believed to be due mainly to the activation of ATF6. Because iPLA2γ amplified the effect of tunicamycin on ATF6 activation, we proceeded to investigate whether this effect on ATF6 activation was associated with up-regulation of ER chaperones. First, it should be noted that cDNA transfection did not independently stimulate increases in GRP94 and GRP78, i.e. there were no significant differences between untransfected and vector-transfected cells (Fig. 4). Brief incubation of GECs overexpressing iPLA2γ with tunicamycin (10 μg/ml, 6 h) did not induce significant increases in GRP94 and GRP78 expression, compared with vector-transfected cells (results not shown). In contrast, incubation of untransfected or vector-transfected GECs with tunicamycin (5 or 10 μg/ml) for 18 h induced modest increases in the expression of GRP94 and GRP78, and this effect was amplified by overexpression of iPLA2γ (Fig. 4, A–C). When cells were pretreated with R-BEL or indomethacin prior to the incubation with tunicamycin, the amplified GRP94 and GRP78 expression was reduced by R-BEL but not by indomethacin (Fig. 4, D–F). Thus, iPLA2γ amplifies tunicamycin-induced up-regulation of ER chaperones, and this effect is dependent on iPLA2γ catalytic activity but not on prostanoids.

FIGURE 4.

iPLA2γ amplifies the tunicamycin-induced up-regulation of ER chaperones in GECs. A–C, rat GECs were untransfected (Untrans) or were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ or empty vector in control. After 24 h, cells were untreated (Untr, or incubated with tunicamycin (Tm, 5 or 10 μg/ml, 18 h). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to GRP94, GRP78, GFP (iPLA2γ), and actin. Tunicamycin (5 and 10 μg/ml) tended to increase GRP94 and GRP78 expression levels in untransfected and vector-transfected (control) cells. This effect was amplified by overexpression of iPLA2γ (A, representative immunoblots; B and C, densitometric quantification). B, GRP94: *, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm 5). *, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm 10). C, GRP78: *, p < 0.05 Tm 10 versus untreated (Untrans); **, p < 0.05 Tm 10 versus untreated (Vector); +, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm 5 and 10), three experiments performed in duplicate. D–F, GECs were untransfected, or were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ. After 24 h, cells were preincubated with R-BEL (5 μm) or indomethacin (Indo, 10 μm) for 30 min. Cells were then treated with Tm (5 μg/ml, 18 h). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to GRP94, GRP78, GFP, and actin. Tunicamycin increased GRP94 and GRP78 expression levels in iPLA2γ-transfected cells. This effect was reduced by R-BEL but not by indomethacin (D, representative immunoblots; E and F, densitometric quantification). E, GRP94: *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated. **, p < 0.001 R-BEL + Tm versus Tm. F, GRP78: *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated. **, p < 0.01 R-BEL + Tm versus Tm, three experiments performed in duplicate.

To verify that endogenous iPLA2γ can also modulate ER chaperone induction, we employed GECs derived from WT and iPLA2γ KO mice. Mouse GECs were incubated with 0.5 or 5 μg/ml tunicamycin for 6 h. iPLA2γ KO cells showed significantly reduced induction of GRP94 and GRP78, compared with WT (Fig. 3, B–D), supporting a role for endogenous iPLA2γ in tunicamycin-induced up-regulation of ER chaperones. After 18 h of incubation with tunicamycin, there were large increases in GRP94 and GRP78 expression, such that there were no significant differences between WT and KO GECs (data not shown).

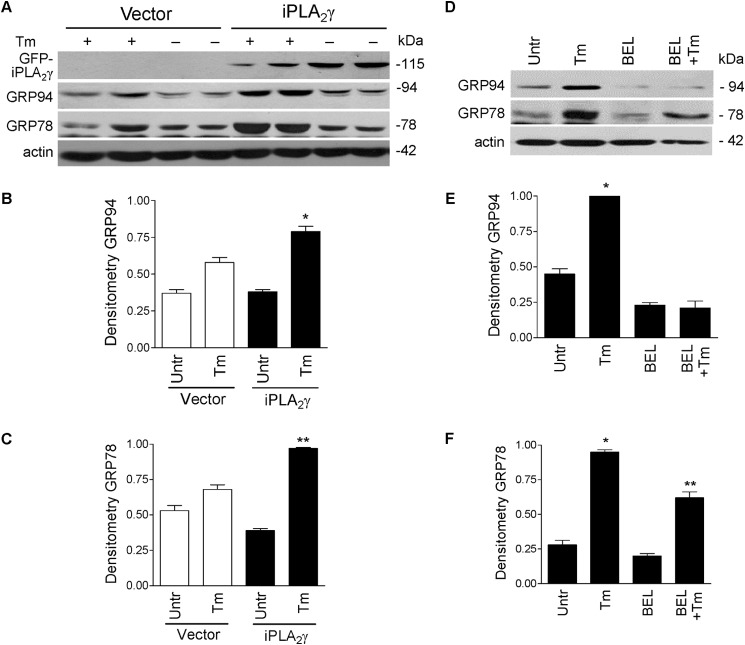

Next, we studied whether comparable effects of iPLA2γ can occur in other cell lines. In COS-1 cells, expression of iPLA2γ amplified tunicamycin-induced up-regulation of GRP94 and GRP78 (Fig. 5, A–C). Furthermore, transfection of iPLA2γ in COS-1 cells independently resulted in a modest but significant increase in ATF6-luciferase reporter activity (Table 2, part A) and, in addition, amplified the tunicamycin-induced stimulation of reporter activity (Table 2, part B). cDNA transfection did not independently stimulate an increase in ATF6-luciferase reporter activity in COS-1 cells (Table 2). In 293T cells, which were reported to express a significant amount of endogenous iPLA2γ (31), tunicamycin induced robust increases in GRP94 and GRP78, and these were reduced substantially when endogenous iPLA2γ was inhibited by R-BEL (Fig. 5, D–F). These results are in keeping with the overexpression or deletion of iPLA2γ in GECs and support the role of iPLA2γ in ATF6 activation/ER chaperone induction.

FIGURE 5.

iPLA2γ amplifies the tunicamycin-induced up-regulation of ER chaperones in COS-1 and 293T cells. A–C, COS-1 cells were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ and were then incubated with tunicamycin (Tm, 10 μg/ml, 18 h), as above. Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to GRP94, GRP78, GFP, and actin. Tunicamycin tended to increase GRP94 and GRP78 expression levels in control cells. This effect was amplified by overexpression of iPLA2γ (A, representative immunoblots; B and C, densitometric quantification). B, GRP94: *, p = 0.0015 Tm versus untreated (iPLA2γ). C, GRP78: *, p < 0.0001 Tm versus untreated (iPLA2γ). **, p = 0.0015 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm), three experiments performed in duplicate. D–F, 293T cells were incubated with Tm and/or R-BEL. Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to GRP94, GRP78, and actin. Tunicamycin increased GRP94 and GRP78 expression levels. This effect was reduced by R-BEL. D, representative immunoblots; E and F, densitometric quantification. E, GRP94: *, p < 0.0001 Tm versus untreated and Tm versus R-BEL + Tm. F, GRP78: *, p < 0.0001 Tm versus untreated and p < 0.001 Tm versus R-BEL + Tm. **, p < 0.001 R-BEL + Tm versus R-BEL, three experiments.

TABLE 2.

Effect of iPLA2γ on ATF6 luciferase activity in COS-1 cells

Parts A and B, COS-1 cells were untransfected or were transiently co-transfected with M1 GFP-iPLA2γ (WT) or vector (in control), plus ATF6 firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase. After 24 h, cells were untreated or incubated with tunicamycin (0.1 μg/ml, 24 h). ATF6 reporter activity is expressed in relative luminescence units (RLU). Part C, COS-1 cells were transiently co-transfected with vector, GFP-iPLA2γ (WT), or GFP-iPLA2γ S511A/S515A, plus ATF6 firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase.

| Transfection/treatment | RLU | |

|---|---|---|

| A. | Untransfected | 1.0 |

| Vector | 1.3 ± 0.2 | |

| GFP-iPLA2γ | 3.6 ± 0.8a | |

| B. | Untransfected/untreated | 1.0 |

| Untransfected/tunicamycin | 16.1 ± 1.4 | |

| Vector/untreated | 1.6 ± 0.5 | |

| Vector/tunicamycin | 9.3 ± 0.7 | |

| GFP-iPLA2γ/untreated | 3.7 ± 1.7 | |

| GFP-iPLA2γ/tunicamycin | 27.5 ± 5.9b | |

| C. | Vector | 1.0 |

| GFP-iPLA2γ | 2.3 ± 0.1c | |

| GFP-iPLA2γ S511A/S515A | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

a p < 0.001 versus vector (four experiments performed in duplicate).

b p < 0.015 versus vector + tunicamycin and versus untransfected + tunicamycin (four experiments performed in duplicate).

c p = 0.005 versus vector (four experiments performed in duplicate).

In a previous study, we demonstrated that mutation of serine 511 and serine 515 to alanines partially reduces the catalytic activity of iPLA2γ and that phosphorylation of serine 511 is associated with an increase in activity (11). To address the role of these phosphorylation sites in the activation of ATF6 by iPLA2γ, COS-1 cells were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ (WT) or GFP-iPLA2γ S511A/S515A. As described above, transfection of GFP-iPLA2γ (WT) independently increased ATF6 response element-luciferase reporter activity, whereas the increase in reporter activity by the S511A/S515A mutant was lower and not significant (Table 2, part C), Experiments to test the role of serine 511 and serine 515 were also performed in GECs (protocol as in Fig. 2A). After treating GECs with tunicamycin, expression of GFP-iPLA2γ (WT) enhanced ATF6 luciferase reporter activity by 29%, compared with vector, although expression of GFP-iPLA2γ S511A/S515A increased reporter activity by only 18% (six experiments). These results imply that the enzymatic activity of iPLA2γ is necessary to enhance ATF6 activation.

iPLA2γ Does Not Amplify Tunicamycin-induced PERK and IRE1α Pathway Activation

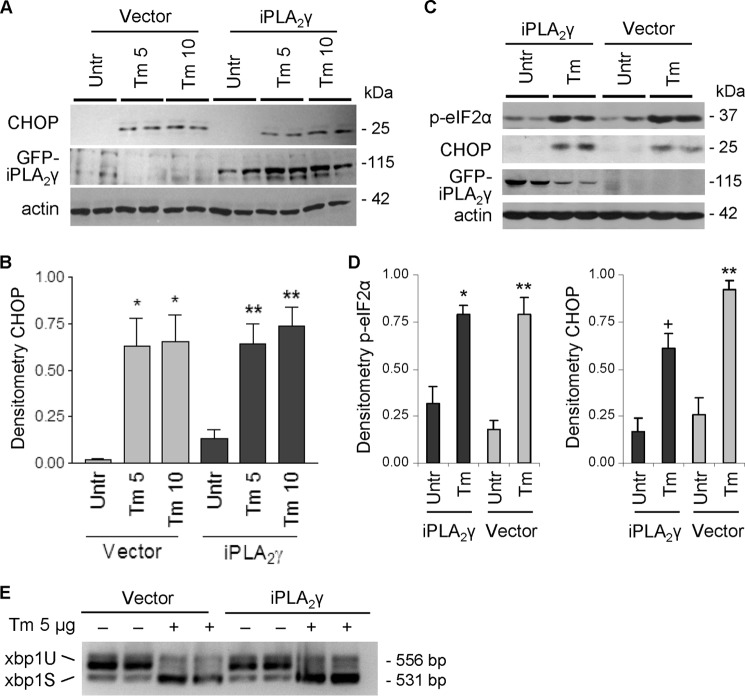

A second aspect of the UPR involves activation of PERK and phosphorylation of eIF2α. This phosphorylation is associated with a global decrease in translation but preferential translation of ATF4, which leads to the induction of several genes, including CHOP, a gene closely associated with apoptosis and/or growth arrest (32). We next studied the effect of iPLA2γ on the PERK pathway. Tunicamycin stimulated induction of C/EBP homologous protein-10 (CHOP) in control (vector-transfected) GECs after 6 h (data not shown) or 18 h (Fig. 6, A and B), but unlike ER chaperones, the stimulation of CHOP was not affected by overexpression of iPLA2γ. By analogy, tunicamycin increased CHOP and eIF2α phosphorylation in control COS-1 cells, and the increases in CHOP and eIF2α phosphorylation were not affected by overexpression of iPLA2γ (Fig. 6, C and D). These results imply that the PERK pathway is not modulated by iPLA2γ. In a third UPR pathway, IRE1α endonuclease activity splices xbp1 mRNA to yield a potent transcriptional activator. To determine whether IRE1α is modulated by iPLA2γ, we monitored xbp1 splicing by RT-PCR. Tunicamycin (6-h incubation) induced nearly complete splicing of xbp1 in both vector (control) and iPLA2γ-transfected cells (Fig. 6E). Complete splicing of xpb1 was evident in control GECs incubated with tunicamycin for 18 h (data not shown). Overexpression of iPLA2γ did not, however, enhance the xbp1 splicing (Fig. 6E). These results indicate that, similar to PERK, the activation of IRE1α was not modulated by iPLA2γ.

FIGURE 6.

PERK and IRE1α pathways are not modulated by iPLA2γ during ER stress. GECs (A, B, and E) or COS-1 cells (C and D) were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ or empty vector in control. After 24 h, cells were untreated (Untr) or were treated with tunicamycin (Tm, 5 or 10 μg/ml in GECs; 10 μg/ml in COS-1 cells) for 18 h. A–D, lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to CHOP, phospho (p)-eIF2α, GFP, or actin. Tunicamycin (5 and 10 μg/ml) increased CHOP and phospho-eIF2α in vector-transfected control cells. The stimulation of CHOP or phospho-eIF2α was not affected by iPLA2γ overexpression. A and C, representative immunoblots; B and D, densitometric quantification. B. *, p < 0.001 Tm 5 and 10 versus untreated (Vector), **, p < 0.01 Tm 5 and 10 versus untreated (iPLA2γ), three experiments performed in duplicate. D, *, p < 0.003; +, p < 0.0002 Tm versus untreated (iPLA2γ); **, p < 0.0001 Tm versus untreated (Vector), 3–4 experiments performed in duplicate. E, mRNA was reverse-transcribed, and PCR was conducted to amplify xbp1 variants. Tunicamycin induced the splicing of 26 bp from xbp1 in control cells, which reflects activation of IRE1α. Activation of IRE1α was not affected by overexpression of iPLA2γ.

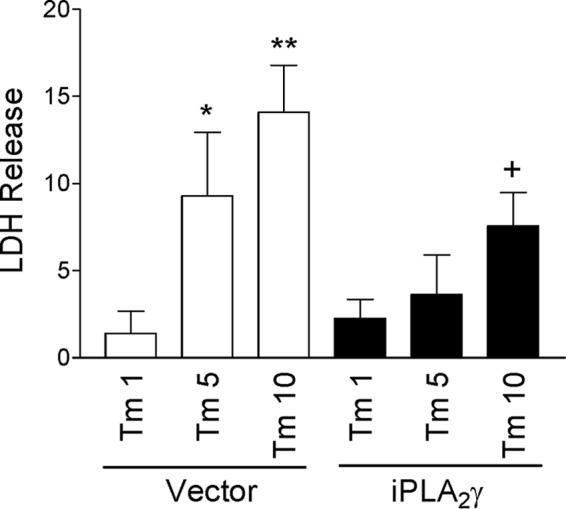

iPLA2γ Reduces Tunicamycin-induced Cell Death

The above experiments showed that iPLA2γ amplified tunicamycin-induced expression of ER chaperones in GECs. This aspect of the UPR is typically cytoprotective, because up-regulation of chaperones enhances the protein-folding capacity of the ER. Based on these results, we hypothesized that the amplification of chaperone induction by iPLA2γ is responsible for limiting cell injury. Prolonged incubation of cells with tunicamycin can induce a cytotoxic ER stress response, which is, at least in part, associated with the induction of CHOP (33). Therefore, we examined the effect of iPLA2γ on cytotoxicity during chronic incubation with tunicamycin. Cytotoxicity was monitored by release of LDH (28). Tunicamycin (5–10 μg/ml, 24-h incubation) significantly induced LDH release in control cells, and this was reduced markedly in GECs overexpressing iPLA2γ (Fig. 7), indicating that iPLA2γ is cytoprotective in tunicamycin-induced cell death.

FIGURE 7.

iPLA2γ reduced tunicamycin-induced cell death. GECs were transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ or empty vector in control. After 24 h, cells were untreated or were treated with tunicamycin (Tm, 1, 5, or 10 μg/ml) for 24 h. Tunicamycin-induced cytotoxicity was monitored by LDH release. The results show Tm-induced LDH release above the values in untreated cells. Tunicamycin (5 and 10 μg/ml) significantly induced LDH release in vector-transfected cells. This effect was reduced in GECs overexpressing iPLA2γ. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 Tm versus untreated (Vector). +, p < 0.01 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm 10), five experiments performed in duplicate.

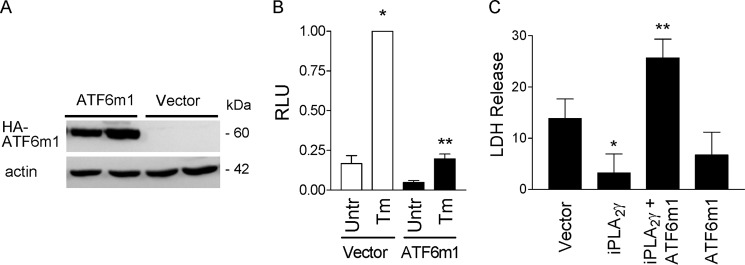

Cytoprotective Effect of iPLA2γ Is Dependent on the ATF6 Pathway

To further investigate whether the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ is dependent on ATF6, we employed a cDNA construct that blocks the activity of endogenous ATF6, ATF6(1–373)m1 (ATF6m1). This construct has point mutations in the basic region of ATF6 (KNR to TAA at amino acids 315–317), which are predicted to disrupt the DNA binding activity of the cytoplasmic domain of ATF6, and acts as a dominant negative as it dimerizes with endogenous ATF6 and prevents its binding to ATF6 DNA-binding sites (20). After transfection of GECs with HA-ATF6m1 cDNA, expression of HA-ATF6m1 protein was readily detectable (Fig. 8A). As expected, ATF6m1 did not activate the ATF6 reporter and completely inhibited induction of the reporter by tunicamycin (Fig. 8B), in keeping with an earlier study (20). Next, we monitored cell death in GECs co-transfected with iPLA2γ and/or ATF6m1. Tunicamycin significantly induced LDH release in vector-transfected control cells (Fig. 8C). Consistent with previous results (Fig. 7), iPLA2γ protected against tunicamycin-induced cell death (Fig. 8C). The protective effect of iPLA2γ was abolished in cells where iPLA2γ was co-transfected with ATF6m1 (Fig. 8C). ATF6m1 alone did not affect tunicamycin-induced cell death. These results indicate that the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ during ER stress is dependent on the ATF6 pathway.

FIGURE 8.

Cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ during ER stress is dependent on the ATF6 pathway. GECs were transiently transfected with HA-ATF6m1 (dominant negative ATF6) or empty vector. A, lysates were immunoblotted with antibody to HA. ATF6m1 expression is presented. B, GECs were transiently co-transfected with ATF6m1 or vector in control, plus ATF6 firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase. Cells were untreated (Untr), or incubated with Tm (0.1 μg/ml, 18 h). ATF6m1 completely inhibited stimulated ATF6 reporter activity. *, p < 0.001 Tm versus untreated (Vector); **, p < 0.001 ATF6m1 versus vector (Tm), two experiments performed in duplicate. RLU, relative luminescence units. C, GECs were transfected with vector, iPLA2γ, ATF6m1, or iPLA2γ + ATF6m1. After 24 h, cells were untreated or were treated with tunicamycin (Tm, 10 μg/ml) for 24 h. The results show Tm-induced LDH release above the values in untreated cells. Tunicamycin induced significant LDH release in vector-transfected control cells. Overexpression of iPLA2γ attenuated the Tm-induced release of LDH. The cytoprotective effect iPLA2γ was reversed by ATF6m1. *, p < 0.05 iPLA2γ versus vector (Tm); **, p < 0.01 iPLA2γ + ATF6m1 versus iPLA2γ (Tm), five experiments performed in duplicate.

To determine whether the protective effect of iPLA2γ on cell death is specifically linked to ER stress or is a general mechanism of cell death, we examined the effect of iPLA2γ on the cytotoxicity of two non-ER stress agents, staurosporine and etoposide. The protocol employed in these experiments was analogous to the one used in Fig. 7. Incubation of vector-transfected GECs with staurosporine (1 μm) increased LDH release by 19 ± 12% (above values in untreated cells), although the increase in iPLA2γ-transfected GECs was 27 ± 17% (three experiments performed in duplicate). Incubation of vector-transfected GECs with etoposide (300 μm) increased LDH release by 13 ± 6%, although the increase in iPLA2γ-transfected GECs was 20 ± 11% (three experiments performed in duplicate). Thus, unlike the protective effect of iPLA2γ in the cell injury induced by the ER stressor, tunicamycin, no protective effect was evident in injury induced by staurosporine and etoposide.

Effect of iPLA2γ on Sterol Regulatory Element-binding Protein (SREBP)-2

During ER stress, ATF6 is released from the ER and translocates to the Golgi, where it is cleaved by the site-1 and site-2 proteases. The cleaved cytosolic fragment of ATF6 migrates to the nucleus to activate gene transcription. It has been reported that SREBPs are also targets of site-1 and site-2 proteases and that SREBP-2 can be activated by ER stress (34). Alternatively, it was also reported that ATF6 can antagonize SREBP-2 (35). Accordingly, we examined whether iPLA2γ could be involved in the activation of SREBP-2 by ER stress and whether this pathway may be functionally important. First, we tested whether tunicamycin activated the SREBP-2 pathway in GECs and whether the effect is modulated by iPLA2γ. To monitor SREBP-2-mediated transcription, we used a protocol analogous to the one in Fig. 2, except that we employed a luciferase reporter driven by the LDLR promoter, which contains a SRE consensus element (LDLR-luciferase) (35). In contrast to the ATF6 response element-luciferase reporter, incubation of GECs with tunicamycin suppressed activation of LDLR-luciferase, and there was no significant modulatory effect of iPLA2γ (Table 3A).

TABLE 3.

Effect of iPLA2γ on LDLR promoter-luciferase reporter activity in GECs

Parts A and B, GECs were untransfected or were transiently co-transfected with GFP-iPLA2γ (WT) or vector (in control), plus LDLR promoter firefly luciferase-reporter and Renilla luciferase. After 24 h, cells were untreated (Untr) or incubated with tunicamycin (0.1 μg/ml, 18 h; part A) or U18666A (2 μg/ml, 18 h; part B). LDLR reporter activity is expressed in relative luminescence units (RLU). Tunicamycin did not stimulate LDLR reporter activity (four experiments performed in triplicate). Although U18666A stimulated LDLR reporter activity, there was no enhancement of this effect by iPLA2γ.

| Transfection/Treatment | RLU | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Vector | Untreated | 0.67 ± 0.18 |

| Tunicamycin | 0.24 ± 0.08 | ||

| iPLA2γ | Untreated | 0.95 ± 0.05 | |

| Tunicamycin | 0.31 ± 0.04 | ||

| B. | Vector | Untreated | 0.75 ± 0.06 |

| U18666A | 1.00 ± 0.00a | ||

| iPLA2γ | Untreated | 0.45 ± 0.05 | |

| U18666A | 0.50 ± 0.09 | ||

a p = 0.04 versus vector/untreated (four experiments performed in triplicate).

We also examined whether iPLA2γ could modulate the activation of LDLR-luciferase by U18666A, a drug that blocks cholesterol transport from late endosomes and lysosomes to the ER, resulting in depletion of ER membrane cholesterol and activation of SREBP-2 (34). In GECs, U18666A had a modest but significant stimulatory effect on LDLR-luciferase, but iPLA2γ did not enhance the effect of U18666A (Table 3, part B). Together, the results indicate that in GECs, ER stress does not appear to activate SREBP-2, and there is no apparent modulatory role of iPLA2γ in this pathway.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, we demonstrated that overexpression of iPLA2γ conferred cytoprotection against complement-dependent GEC injury (12) and that full-length iPLA2γ WT is, in part, localized at the ER (11). In this study, we addressed ER stress as a potential mechanism of iPLA2γ-mediated cytoprotection. We demonstrate that in GECs, iPLA2γ amplified the activation of ATF6 and the up-regulation of the ER chaperones, GRP94 and GRP78 (Figs. 2 and 4). Conversely, deletion of iPLA2γ blunted these responses (Fig. 3). Effects of iPLA2γ on ATF6 and ER chaperones were dependent on iPLA2γ catalytic activity but not on prostanoids (Fig. 2). Furthermore, full ATF6 amplification occurred only when the full-length iPLA2γ was expressed, but not an N-terminally truncated mutant, which does not associate with the ER membrane (Fig. 2), or the S511A/S515A mutant (Table 2, part C, and under “Results”). Unlike the ATF6 pathway, the activation of the other two UPR pathways, PERK and IRE1α, was not modulated by iPLA2γ (Fig. 6). Overexpression of iPLA2γ in GECs reduced tunicamycin-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 7). Moreover, the cytoprotective effect iPLA2γ was reversed by dominant negative ATF6 (Fig. 8). Taken together, the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ during ER stress is dependent on the ATF6 pathway.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that activation of the ATF6 UPR pathway and up-regulation of the ER chaperones can be enhanced via iPLA2γ catalytic activity. Results obtained in an overexpression system need to be interpreted carefully, because the levels of overexpression could be supra-physiological. Indeed, when tested by quantitative PCR, the iPLA2γ mRNA level was ∼18-fold higher in GECs expressing GFP-iPLA2γ, compared with control GECs transfected with vector (Table 1). However, when iPLA2 enzymatic activities in cell lysates were previously compared between transfected and control cells, using an in vitro assay, the difference was only ∼2-fold (11). Similarly, prostaglandin E2 production between vector- and GFP-iPLA2γ-transfected GECs increased ∼2-fold (11), implying that ectopic iPLA2γ was expressed at twice the level of endogenous iPLA2γ. These results suggest that iPLA2γ mRNA is not translated efficiently into catalytically active enzyme, and the total amount of iPLA2γ activity in GECs was most likely within the physiological range. Furthermore, the results with overexpression were supported by complementary experiments, which employed the iPLA2γ inhibitor, R-BEL, and iPLA2γ KO cells. Both approaches demonstrated analogous actions of endogenous iPLA2γ, strengthening the conclusion that iPLA2γ amplifies the induction of ER chaperones via ATF6 activation. It remains to be determined, however, if the iPLA2γ expression level is regulated in GECs under various pathological conditions. By analogy to GECs, the role of iPLA2γ in the induction of ER stress was confirmed in COS-1 and 293T cells (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Thus, the role of iPLA2γ in ER stress was not restricted to a single cell type.

We and others have shown functional coupling of iPLA2γ with cyclooxygenases, as activation of iPLA2γ results in release of arachidonic acid and production of prostanoids (12, 31). In this study, we demonstrated that the effect of iPLA2γ on tunicamycin-mediated activation of ATF6 and up-regulation of ER chaperones was, however, independent of prostanoids (Fig. 2). Therefore, the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ in the model of tunicamycin-induced cell death would probably also be prostanoid-independent. In contrast, cytoprotection by iPLA2γ against complement-induced GEC injury was partially reversed by indomethacin, suggesting that it was at least in part mediated by prostanoids (12). Most likely, iPLA2γ exerts cytoprotection via cyclooxygenase-dependent and -independent mechanisms depending on the cell type and context. In this study, the cytoprotective effect of iPLA2γ was associated with the activation of ATF6 (Fig. 8). Cleaved ATF6 can activate transcription of multiple genes (36). A number of these are chaperones or factors within chaperone pathways, including BiP, GRP94, heat shock protein-40, calreticulin, ATF4, XBP1, and others. Up-regulation of such genes potentially enhances the chaperoning capacity of a cell, thereby alleviating adverse effects of protein misfolding and reducing cytotoxicity. Furthermore, it should also be considered that mechanisms other than ATF6 activation at the ER could contribute to iPLA2γ cytoprotection; for example, the action of iPLA2γ could involve reducing lipid peroxidation (4, 6). In GECs, a portion of iPLA2γ was localized at the mitochondria (11). Thus, by analogy to its action in kidney cortical preparations, iPLA2γ may protect GEC mitochondria from oxidant-induced lipid peroxidation and dysfunction (37).

Similarly to iPLA2γ, iPLA2β was protective in complement-mediated cellular injury (12). In contrast, cytotoxic effects of PLA2s have also been described. Secretory PLA2s facilitate various forms of inflammatory tissue injury. Cytosolic PLA2α was shown to exacerbate cell death induced by complement and hydrogen peroxide and was reported to disrupt the structure of cellular organelles (28, 38). At the same time cytosolic PLA2α enhanced the activation of a cytoprotective UPR, which attenuated cytotoxicity (28). Both cytosolic PLA2α and iPLA2β were implicated in promoting or reducing apoptotic cell death, respectively (38). These complex and apparently conflicting effects of the PLA2 isoforms could be related to the subcellular localization of the enzymes and their site of activation, as well as the temporal activation pattern during the course of cell injury. Moreover, the effects of the PLA2s may be directly due to PLA2-mediated phospholipid hydrolysis/remodeling or associated with the production of pro- or anti-inflammatory mediators from arachidonic acid or lysophospholipid release (38).

The mechanism(s) by which iPLA2γ stimulated ATF6 could potentially involve ER membrane lipids. Perturbation of cellular lipid composition was shown to activate the UPR in several cells. For example, UPR signaling was enhanced in cholesterol-loaded macrophages (39), in liver of mice fed a high fat diet (40), and in pancreatic beta cells exposed to saturated fatty acids (41). The precise biochemical mechanisms by which perturbation of the cellular lipid activates UPR pathways in these cells remain unknown. It was proposed that altered membrane lipid composition may potentially alter Ca2+ homeostasis by inhibition of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (40). This may lead to Ca2+ depletion from the ER, which in turn activates the UPR by interfering with Ca2+-dependent chaperones and enzymes required for protein folding (40). Alternatively, direct sensing of lipid perturbation may contribute to activation of ATF6. For example, perturbation of the lipid bilayer of the ER by the expression of a tail-anchored ER membrane protein resulted in the selective activation of ATF6, in the absence of IRE1α and PERK activation (and without ER Ca2+ depletion) (42). Conversely, a recent study has demonstrated that saturation of membrane lipids promoted selective IRE1α and PERK activation by enhancing dimerization via their transmembrane domains (43). Defining the precise mechanism of ATF6 activation by iPLA2γ will require further investigation.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate a key relationship between iPLA2γ and ATF6 activation. Additionally, we have shown that iPLA2γ plays a cytoprotective role involving the ATF6 pathway of the UPR. Stimulation of iPLA2γ enzymatic activity represents a potentially novel approach to limiting GEC injury in proteinuric glomerular diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Gross (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) for providing iPLA2γ knock-out mice and Lamine Aoudjit (McGill University) for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 HL118639. This work was also supported by Research Grants MOP-53264, MOP-133492, MOP-125988, and MOP-53335 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, and the Catherine McLaughlin Hakim Chair (to A. V. C.).

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- BEL

- bromoenol lactone

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GEC

- glomerular epithelial cell

- iPLA2

- calcium-independent phospholipase A2

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- LDLR

- low density lipoprotein receptor

- PERK

- protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- Tm

- tunicamycin

- CHOP

- C/EBP homologous protein-10.

REFERENCES

- 1. Murakami M., Kudo I. (2002) Phospholipase A2. J. Biochem. 131, 285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Six D. A., Dennis E. A. (2000) The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A(2) enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488, 1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Funk C. D. (2001) Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science 294, 1871–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cummings B. S., McHowat J., Schnellmann R. G. (2002) Role of an endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-independent phospholipase A(2) in oxidant-induced renal cell death. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283, F492–F498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mancuso D. J., Jenkins C. M., Sims H. F., Cohen J. M., Yang J., Gross R. W. (2004) Complex transcriptional and translational regulation of iPLAγ resulting in multiple gene products containing dual competing sites for mitochondrial or peroxisomal localization. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 4709–4724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kinsey G. R., Blum J. L., Covington M. D., Cummings B. S., McHowat J., Schnellmann R. G. (2008) Decreased iPLA2γ expression induces lipid peroxidation and cell death and sensitizes cells to oxidant-induced apoptosis. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1477–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cummings B. S., McHowat J., Schnellmann R. G. (2004) Role of an endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 in cisplatin-induced renal cell apoptosis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 308, 921–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gadd M. E., Broekemeier K. M., Crouser E. D., Kumar J., Graff G., Pfeiffer D. R. (2006) Mitochondrial iPLA2 activity modulates the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and influences the permeability transition. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6931–6939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mancuso D. J., Kotzbauer P., Wozniak D. F., Sims H. F., Jenkins C. M., Guan S., Han X., Yang K., Sun G., Malik I., Conyers S., Green K. G., Schmidt R. E., Gross R. W. (2009) Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ leads to alterations in hippocampal cardiolipin content and molecular species distribution, mitochondrial degeneration, autophagy, and cognitive dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35632–35644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mancuso D. J., Sims H. F., Yang K., Kiebish M. A., Su X., Jenkins C. M., Guan S., Moon S. H., Pietka T., Nassir F., Schappe T., Moore K., Han X., Abumrad N. A., Gross R. W. (2010) Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ prevents obesity and insulin resistance during high fat feeding by mitochondrial uncoupling and increased adipocyte fatty acid oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36495–36510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elimam H., Papillon J., Takano T., Cybulsky A. V. (2013) Complement-mediated activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ: role of protein kinases and phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 3871–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen D., Papillon J., Aoudjit L., Li H., Cybulsky A. V., Takano T. (2008) Role of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in complement-mediated glomerular epithelial cell injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 294, F469–F479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Araki K., Nagata K. (2011) Protein folding and quality control in the ER. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ron D., Walter P. (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yoshida H. (2007) ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 274, 630–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hetz C. (2012) The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang K., Kaufman R. J. (2008) From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 454, 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cybulsky A. V. (2013) The intersecting roles of endoplasmic reticulum stress, ubiquitin- proteasome system, and autophagy in the pathogenesis of proteinuric kidney disease. Kidney Int. 84, 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutkowski D. T., Hegde R. S. (2010) Regulation of basal cellular physiology by the homeostatic unfolded protein response. J. Cell Biol. 189, 783–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y., Shen J., Arenzana N., Tirasophon W., Kaufman R. J., Prywes R. (2000) Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27013–27020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castoreno A. B., Wang Y., Stockinger W., Jarzylo L. A., Du H., Pagnon J. C., Shieh E. C., Nohturfft A. (2005) Transcriptional regulation of phagocytosis-induced membrane biogenesis by sterol regulatory element binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13129–13134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jat P. S., Noble M. D., Ataliotis P., Tanaka Y., Yannoutsos N., Larsen L., Kioussis D. (1991) Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 5096–5100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coers W., Reivinen J., Miettinen A., Huitema S., Vos J. T., Salant D. J., Weening J. J. (1996) Characterization of a rat glomerular visceral epithelial cell line. Exp. Nephrol. 4, 184–192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mancuso D. J., Sims H. F., Han X., Jenkins C. M., Guan S. P., Yang K., Moon S. H., Pietka T., Abumrad N. A., Schlesinger P. H., Gross R. W. (2007) Genetic ablation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ leads to alterations in mitochondrial lipid metabolism and function resulting in a deficient mitochondrial bioenergetic phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34611–34622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mundel P., Reiser J., Kriz W. (1997) Induction of differentiation in cultured rat and human podocytes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saleem M. A., O'Hare M. J., Reiser J., Coward R. J., Inward C. D., Farren T., Xing C. Y., Ni L., Mathieson P. W., Mundel P. (2002) A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 630–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mundel P., Reiser J., Zúñiga Mejía Borja A., Pavenstädt H., Davidson G. R., Kriz W., Zeller R. (1997) Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 236, 248–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cybulsky A. V., Takano T., Papillon J., Khadir A., Liu J., Peng H. (2002) Complement C5b-9 membrane attack complex increases expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in glomerular epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41342–41351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lytton J., Westlin M., Hanley M. R. (1991) Thapsigargin inhibits the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase family of calcium pumps. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 17067–17071 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren G., Takano T., Papillon J., Cybulsky A. V. (2010) Cytosolic phospholipase A2-α enhances induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 468–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murakami M., Masuda S., Ueda-Semmyo K., Yoda E., Kuwata H., Takanezawa Y., Aoki J., Arai H., Sumimoto H., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Nakatani Y., Kudo I. (2005) Group VIB Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2γ promotes cellular membrane hydrolysis and prostaglandin production in a manner distinct from other intracellular phospholipases A2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14028–14041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zinszner H., Kuroda M., Wang X., Batchvarova N., Lightfoot R. T., Remotti H., Stevens J. L., Ron D. (1998) CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12, 982–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cybulsky A. V., Takano T., Papillon J., Kitzler T. M., Bijian K. (2011) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in glomerular epithelial cell injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F496–F508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lhoták S., Sood S., Brimble E., Carlisle R. E., Colgan S. M., Mazzetti A., Dickhout J. G., Ingram A. J., Austin R. C. (2012) ER stress contributes to renal proximal tubule injury by increasing SREBP-2-mediated lipid accumulation and apoptotic cell death. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 303, F266–F278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zeng L., Lu M., Mori K., Luo S., Lee A. S., Zhu Y., Shyy J. Y. (2004) ATF6 modulates SREBP2-mediated lipogenesis. EMBO J. 23, 950–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Belmont P. J., Chen W. J., San Pedro M. N., Thuerauf D. J., Gellings Lowe N., Gude N., Hilton B., Wolkowicz R., Sussman M. A., Glembotski C. C. (2010) Roles for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and the novel endoplasmic reticulum stress response gene Derlin-3 in the ischemic heart. Circ. Res. 106, 307–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kinsey G. R., McHowat J., Beckett C. S., Schnellmann R. G. (2007) Identification of calcium-independent phospholipase A2γ in mitochondria and its role in mitochondrial oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292, F853–F860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cummings B. S., McHowat J., Schnellmann R. G. (2000) Phospholipase A(2)s in cell injury and death. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 294, 793–799 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Feng B., Yao P. M., Li Y., Devlin C. M., Zhang D., Harding H. P., Sweeney M., Rong J. X., Kuriakose G., Fisher E. A., Marks A. R., Ron D., Tabas I. (2003) The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 781–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fu S., Yang L., Li P., Hofmann O., Dicker L., Hide W., Lin X., Watkins S. M., Ivanov A. R., Hotamisligil G. S. (2011) Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature 473, 528–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cunha D. A., Hekerman P., Ladrière L., Bazarra-Castro A., Ortis F., Wakeham M. C., Moore F., Rasschaert J., Cardozo A. K., Bellomo E., Overbergh L., Mathieu C., Lupi R., Hai T., Herchuelz A., Marchetti P., Rutter G. A., Eizirik D. L., Cnop M. (2008) Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Cell Sci. 121, 2308–2318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maiuolo J., Bulotta S., Verderio C., Benfante R., Borgese N. (2011) Selective activation of the transcription factor ATF6 mediates endoplasmic reticulum proliferation triggered by a membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7832–7837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Volmer R., van der Ploeg K., Ron D. (2013) Membrane lipid saturation activates endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response transducers through their transmembrane domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4628–4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]