Abstract

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a key regulator of cancer progression and the inflammatory effects of disease. To identify inhibitors of DNA binding to NF-κB, we developed a new homogeneous method for detection of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. This method, which we refer to as DSE-FRET, is based on two phenomena: protein-dependent blocking of spontaneous DNA strand exchange (DSE) between partially double-stranded DNA probes, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). If a probe labeled with a fluorophore and quencher is mixed with a non-labeled probe in the absence of a target protein, strand exchange occurs between the probes and results in fluorescence elevation. In contrast, blocking of strand exchange by a target protein results in lower fluorescence intensity. Recombinant human NF-κB (p50) suppressed the fluorescence elevation of a specific probe in a concentration-dependent manner, but had no effect on a non-specific probe. Competitors bearing a NF-κB binding site restored fluorescence, and the degree of restoration was inversely correlated with the number of nucleotide substitutions within the NF-κB binding site of the competitor. Evaluation of two NF-κB inhibitors, Evans Blue and dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin ([−]-DHMEQ), was carried out using p50 and p52 (another form of NF-κB), and IC50 values were obtained. The DSE-FRET technique also detected the differential effect of (−)-DHMEQ on p50 and p52 inhibition. These data indicate that DSE-FRET can be used for high throughput screening of anticancer drugs targeted to DNA-binding proteins.

Keywords: Antineoplastic agents, dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin, DNA-binding proteins, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, NF-κB

DNA-binding proteins such as transcription factors play key roles in normal biological processes and in development of disease. Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a DNA-binding protein involved in inflammation and tumorigenesis, and thus inhibition of NF-κB signaling is a potential target for cancer therapy; however, there are few direct inhibitors of NF-κB binding to DNA. In general, DNA-binding proteins are attractive therapeutic targets,(1,2) but conventional methods for detecting protein–DNA binding, such as a gel-shift assay,(3) DNA footprinting assay,(4,5) and ELISA,(6) are laborious and time-consuming, and thus not amenable to combinatorial screening.

Fluorescent-based homogeneous methods have been exploited for detection of sequence-specific protein–DNA binding,(7–9) including use of the split probe “molecular beacon” method in a FRET-based assay.(7) In this method, a DNA fragment containing a protein binding site is split into two parts in the middle of the site. One part is labeled with a donor fluorophore and the other has an acceptor fluorophore. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between the two fluorophores is produced as a result of protein-dependent association of the split DNA fragments. The molecular beacon is simple in principle and is cost-effective. However, probe designs are complicated for three reasons. First, protein-independent association of the two DNA molecules may occur. Second, fluorophores can disturb protein–DNA binding or fluorescence can be changed by the protein because the fluorophores are introduced into nucleotides proximal to the protein binding site. Finally, nicks in the associated DNA fragment can influence protein binding because proteins interact with the phosphate backbone, in addition to the bases. Fluorescence-based DNA footprinting can overcome these drawbacks.(8,9) This method is based on a DNA-binding protein protecting its target DNA against exonuclease III digestion. However, the method requires careful quality control of exonuclease III activity to obtain stable data, and the half-life of the protein–DNA complex must be long compared with the time required for the exonuclease III reaction.

The Holliday junction is a four-way DNA structure that is the central intermediate in homologous recombination. Branches of the structure migrate spontaneously in vitro as a result of strand exchange between two DNA molecules, and DNA-binding proteins including the histone octamer, p53, TRF1, and TRF2 suppress the strand exchange.(10–12) We have found that NF-κB also suppresses this strand exchange in vitro. Based on these findings, we developed a new homogeneous method for detection of protein–DNA binding and screening of drugs targeting DNA-binding proteins.

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotides

The following probe oligonucleotides were made for NF-κB-DSE-FRET (F, 6FAM; D, DABCYL; lowercase letters, single-stranded tail; underline, NF-κB binding site): 5′-FAG TTG AGG GGA CTT TCC CAG GCG ACT CAC TAT AGG Cgg tgt ctc gct cgc-3′ (NF-01F), 5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG CGA CTC ACT ATA GGc acc aca cca ttc cc-3′ (NF-13), 5′-ggg aat ggt gtg gtG CCT ATA GTG AGT CGC CTG GGA AAG TCC CCT CAA CTD-3′ (NF-14D), 5′-gcg agc gag aca ccG CCT ATA GTG AGT CGC CTG GGA AAG TCC CCT CAA CT-3′ (NF-02). To prepare probes, 0.5 μM of each oligonucleotide was mixed in annealing buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.9], 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA), denatured for 2 min at 95°C, and then cooled gradually to allow annealing. Duplexes were stored at 4°C and diluted with binding buffer (10 mM HEPES–NaOH [pH 7.9], 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P40) before use. Oligonucleotides were purchased from Japan Bio Services (Saitama, Japan). All other chemicals were reagent grade or better and were obtained from Wako (Tokyo, Japan).

Protein preparation and DNA binding assay

The GST-fusion recombinant human NF-κB proteins (p50, p52) were expressed and purified(13) and glutathione was removed by dialysis. In general, DNA-binding experiments were carried out in the following manner: 5 μL NF-D1 (consisting of NF-01F and NF-14D) and 5 μL protein in binding buffer were incubated in a 96-well (half-area) microplate for 30 min at room temperature. Next, 40 μL NF-D2 (consisting of NF-02 and NF-13) was added and allowed to incubate for another 60 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured at 535 nm after excitation at 485 nm using an EnVision microplate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). In experiments with inhibitor, 0.5 μL inhibitor, 5 μL NF-D1, and 4.5 μL protein in binding buffer were incubated before addition of 40 μL NF-D2.

To obtain an IC50, the following equation was solved using the “solver” add-on in Microsoft Excel:

|

(1) |

where Y is the observed fluorescence, X is the inhibitor concentration, A is the lowest fluorescence, B is the highest fluorescence, and C gives the largest absolute value of the slope of the curve.

S/B was obtained by the following formula:

| (2) |

where A is the mean fluorescence of four wells in the absence of protein and P is the mean florescence of four wells in the presence of protein.

Z′-factors were obtained as follows:

| (3) |

where A is the mean fluorescence value of four wells without protein, P is the mean florescence of four wells with protein, SDA is the standard deviation of A, and SDP is the standard deviation of P.

Results

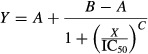

The principle of DSE-FRET is illustrated in Figure 1. Two partially double-stranded DNA probes, named D1 and D2, are used. Each probe has a double-stranded region containing a protein binding site and two single-stranded tails. One strand of D1 is labeled with a fluorophore at the 5′-end and the other is labeled with a quencher at the 3′-end. The fluorophore and quencher are placed at the same end of the double-stranded region; therefore, the fluorescence of the fluorophore is quenched. The tails of D1 are complementary to those of D2, so that D1 hybridizes with D2 to form a four-way structure. As the double-stranded regions of the two probes have identical sequences, the junction of the structure migrates spontaneously, followed by irreversible dissociation to give two fully double-stranded duplexes. In other words, strand exchange occurs between D1 and D2. As a result, the quencher-labeled strand of D1 is exchanged for its non-labeled counterpart in D2; therefore, fluorescence is restored. DNA-binding proteins bind to the duplex and block strand exchange, thereby suppressing the fluorescence elevation.

Figure 1.

Principles of the DSE-FRET assay. (a) In the absence of target protein, strand exchange between D1 and D2 will occur and fluorescence will be elevated. (b) In the presence of target protein, strand exchange will not occur and fluorescence will remain quenched.

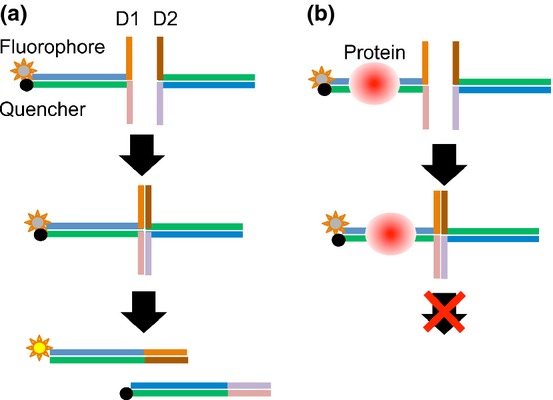

To illustrate the method, we attempted to detect the NF-κB (p50) interaction with DNA. Nuclear factor-κB plays a pivotal role in the coordinated transcription of multiple inflammatory genes and is a probable drug target.(14–16) Two probes, NF-D1 and NF-D2, were prepared to test quantitative detection of p50 binding to DNA. Their double-stranded regions are identical and include an NF-κB binding sequence, d(GGGACTTTCC). These probes interact with each other through their single-stranded tails and are then involved in a strand exchange reaction. Each strand of NF-D1 was labeled with 6FAM and DABCYL at the double-stranded terminus. NF-D1, various concentrations of recombinant p50, and NF-D2 were mixed in a half-area 96-well microplate and changes in fluorescence were measured. Time courses of these changes are shown in Figure 2. The fluorescence signal of NF-D1 increased rapidly within 30 min after addition of NF-D2 and was fivefold higher than that of NF-D1 alone at 60 min in the absence of p50. Fluorescence elevation was suppressed in a p50 concentration-dependent manner by half at 40 nM p50 and almost completely at 320 nM p50.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent suppression of DNA strand exchange by p50. (a) Five microliters of 40 nM NF-D1 was mixed with 5 μL of 0 nM (open circles), 400 nM (open squares), 800 nM (closed squares), 1600 nM (open triangles), or 3200 nM (closed triangles) p50 and incubated for 30 min. Then, 40 μL of 10 nM NF-D2 was added and fluorescence was measured; thus, the final concentrations of p50 were 0, 40, 80, 160, and 320 nM, respectively. Closed circles with a dotted line represent NF-D1 alone. (b) Fluorescence at 60 min for a positive control completely exchanged product (NF-01F + NF-02, named NF-01F02), an exchanged product (NF-D1 + NF-D2), and an unexchanged product (NF-D1 alone) with 0 or 320 nM p50. Error bars represent ±3 SD (n = 4).

Duplex NF-01F02, which consists of NF-01F and NF-02, was prepared as a positive control as a completely exchanged product. Fluorescence of NF-01F02 was not affected by p50 (Fig. 2). We then optimized the concentrations of NF-D1 and NF-D2. Varied concentrations of NF-1D (1, 2, and 4 nM) were mixed with twofold or fourfold amounts of NF-2D in the presence (40 nM) or absence of p50. As shown in Table 1, the combination of 2 nM NF-D1 and 8 nM NF-D1 showed the highest Z′-factor (0.93). S/B values (ratio in the absence to presence of p50) were 1.9–2.3 and were not influenced by the DNA concentration. Therefore, we used 2 nM NF-D1 with 8 nM NF-D2 in the following assays.

Table 1.

Optimization of probe concentration

| D1 (nM) | D2 (nM) | S/B | Z′-factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 8 | 1.9 | 0.77 |

| 2 | 4 | 2.3 | 0.90 |

| 2 | 8 | 2.2 | 0.93 |

| 1 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.83 |

| 1 | 8 | 1.9 | 0.82 |

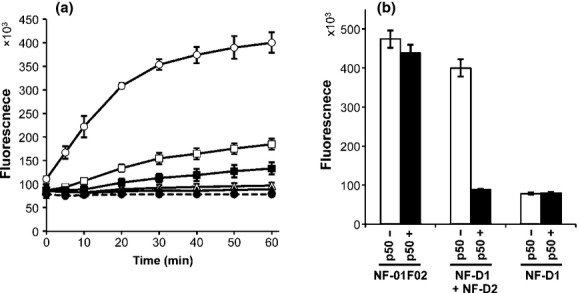

We examined the specificity of the assay by using double-stranded competitor DNA. NF-cpt1 is a specific competitor DNA bearing a NF-κB binding site. NF-cpt2, NF-cpt3, NF-cpt4, and NF-cpt5 are non-specific competitors with one to four nucleotides substituted in the NF-κB binding site. NF-cpt1 completely restored the fluorescence suppressed by p50 (Fig. 3). The restoration level decreased as the number of substituted nucleotides in non-specific competitors increased and NF-cpt5, with four substituted nucleotides, had little effect on p50 binding. For further evaluation of specificity, we prepared non-specific probes, NFs-D1 and NFs-D2, with nucleotide substitutions as in NF-cpt5. The fluorescence signal of the nonspecific probes was not affected by p50 (Fig. 3). Hence, we concluded that p50 suppressed strand exchange in a sequence-specific manner.

Figure 3.

Specificity of DSE-FRET. (a) 2.5 μL of 2000 nM competitor was mixed with 2.5 μL of 800 nM p50 and incubated for 30 min. Then, 5 μL of 20 nM NF-D1 was added and incubated for a further 30 min. Finally, 40 μL of 10 nM NF-D2 was added and fluorescence was measured: NF-D1 and NF-D2 without p50 (white bar), without competitor (black bar), and with competitors (gray bars). Horizontally and diagonally striped bars indicate non-specific probes (NFs-D1 + NFs-D2) without and with p50, respectively. (b) Sequences of the competitor upper strand are shown: underline, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) binding site; bold type, substituted nucleotide in binding site. Error bars represent ±3 SD (n = 4).

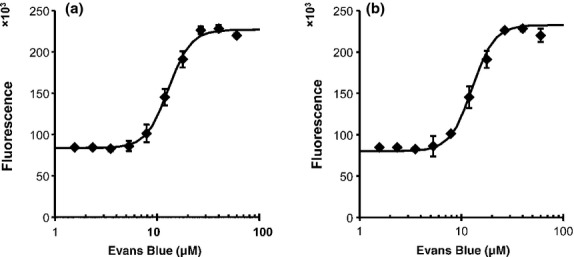

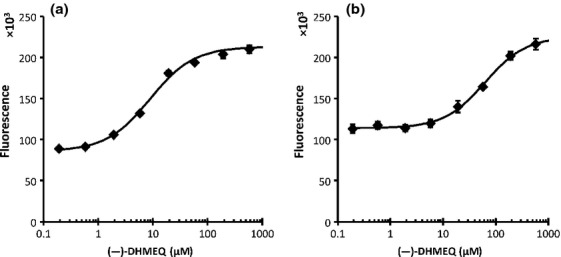

A 10-point dose–response experiment with Evans Blue (EB) was also carried out. One hundred μM Evans Blue inhibits NF-κB binding to DNA by EMSA and has been suggested to bind non-covalently to the p50 DNA binding region by molecular modeling.(17) In DSE-FRET, 10 μM EB showed little effect on p50, but 30 μM EB inhibited p50 completely (Fig. 4). Evans Blue also inhibited p52 in a similar fashion. The IC50 values of EB for p50 and p52 inhibition were 12.9 and 12.8 μM, respectively. We also showed that our method can be used for evaluation of an uncompetitive inhibitor, (−)-DHMEQ, which binds covalently to a specific Cys residue of Rel family proteins to inhibit their DNA binding.(18,19) We detected an inhibitory effect of (−)-DHMEQ on p50 and p52 by DSE-FRET (Fig. 5). As shown previously,(19) (−)-DHMEQ was less potent against p52 (IC50 62.5 μM) compared to p50 (IC50 8.8 μM).

Figure 4.

Dose–response of Evans Blue (EB). Half a microliter of various concentrations of EB was mixed with 4.5 μL of 890 nM p50 (a) or p52 (b) and incubated for 30 min. Then, 5 μL of 20 nM NF-D1 was added and incubated for a further 30 min. Finally, 40 μL of 10 nM NF-D2 was added and fluorescence was measured. Horizontal axes show the concentration of EB in incubations with protein and NF-D1. Error bars represent ±SD (n = 4).

Figure 5.

Dose–response of dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin ([−]-DHMEQ). Half a microliter of various concentrations of (−)-DHMEQ was mixed with 4.5 μL of 440 nM p50 (a) or p52 (b) and incubated for 30 min. Then, 5 μL of 20 nM NF-D1 was added and incubated for a further 30 min. Finally, 40 μL of 10 nM NF-D2 was added and fluorescence was measured. Horizontal axes show the concentrations of (−)-DHMEQ in incubations with protein and NF-D1. Error bars represent ±SD (n = 4).

Discussion

The DSE-FRET technique can detect protein–DNA interaction quantitatively and specifically using a simple procedure; just mix and measure. It detected p50 binding with a high Z′-factor and a dose–response analysis was carried out with two types of inhibitor (EB and (−)-DHMEQ). Moreover, the differential effect of (−)-DHMEQ on p50 and p52 was well displayed. Yamamoto et al. found that (−)-DHMEQ inhibited p50 more strongly than p52 in EMSA analysis.(19) The same preference of the inhibitor was shown by DSE-FRET, with the IC50 for inhibition of p50 being sevenfold lower than that for p52. However, the amount of (−)-DHMEQ required to inhibit the proteins differed between the two methods. A (−)-DHMEQ concentration fourfold that of p50 (80–20 μM) inhibited protein binding completely in EMSA,(19) whereas a (−)-DHMEQ concentration 44-fold that of p50 (8.8–0.2 μM) was required to inhibit half of the p50 binding in DSE-FRET. In contrast, inhibition of (−)-DHMEQ to p52 was shown only by DSE-FRET. The basis for these differences is unclear.

As a stable and homogeneous assay, DSE-FRET is particularly useful for high throughput screening. These features are particularly important for initial screening of a huge combinatorial library. Although we carried out the assay in a 96-well (half area) format, a 384-well format can be used with appropriate specialized equipment. The probes used in DSE-FRET consist of a double-stranded moiety and two single-stranded tails. Inadequate intra- and intermolecular hybridization of tails interferes with appropriate formation of a four-way junction and markedly reduces the efficiency of strand exchange. Thus, we evaluated 13 tails before choosing the tails used here. These tails were also confirmed to not have protein binding sequences using the transcription factor analysis tool TFSearch (version 1.3 online, http://mbs.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html). Therefore, these tails may be applicable universally. The double-stranded moiety should have a sequence that allows protein binding, but is otherwise not restricted in sequence. Taken together, these features make design of a probe for DSE-FRET as easy as that for EMSA.

To our knowledge, this is the first report to show that NF-κB blocks spontaneous strand exchange. Several proteins, including histone octamer, p53, TRF1, and TRF2, have also been found to block strand exchange.(10–12) However, this blockage can be explained based on particular features of these proteins: thus, the histone octamer forms a large protein–DNA complex and the other proteins have junction-binding activity. Panyutin and Hsieh(20) found that spontaneous strand exchange is also blocked by a mismatch, which suggests that this process may be blocked easily by a small energy barrier.

In this paper, we established a novel technique to identify NF-κB inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Nuclear factor-κB is a desirable target for therapy in various cancers and inflammatory diseases.(21,22) In most cancer cells, NF-κB is localized in the nucleus and is constitutively active. This persistent activity of nuclear NF-κB protects cancer cells from apoptotic cell death. Therefore, anticancer drug targeting of NF-κB may have great therapeutic value by inhibiting cell growth or increasing the sensitivity of conventional chemotherapy. We believe that the DSE-FRET assay will be a powerful tool to isolate novel NF-κB inhibitors that inhibit DNA binding activity and cancer growth. We also found that DNA binding of transcription factors SP1 and AP1 (c-jun) can be detected by DSE-FRET (data not shown). Therefore, DSE-FRET may be applicable to detection of many DNA-binding proteins.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out as part of the Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P-Direct), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Disclosure Statement

H.T. owns stock in MiRTeL Inc. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Latchman DS. Transcription factors as potential targets for therapeutic drugs. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2000;1:57–61. doi: 10.2174/1389201003379022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darnell JE., Jr Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:740–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garner MM, Revzin A. A gel electrophoresis method for quantifying the binding of proteins to specific DNA regions: application to components of the Escherichia coli lactose operon regulatory system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:3047–60. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried M, Crothers DM. Equilibria and kinetics of lac repressor-operator interactions by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:6505–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.23.6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galas DJ, Schmitz A. DNAse footprinting: a simple method for the detection of protein-DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:3157–70. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gubler ML, Abarzúa P. Nonradioactive assay for sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Biotechniques. 1995;18:1008, 1011–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heyduk T, Heyduk E. Molecular beacons for detecting DNA binding proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:171–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, Li T, Guo X, Lu Z. Exonuclease III protection assay with FRET probe for detecting DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Ji M, Hou P, Lu Z. Exo-dye-based assay for rapid, inexpensive, and sensitive detection of DNA-binding proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigoriev M, Hsieh P. A histone octamer blocks branch migration of a Holliday junction. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7139–50. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prabhu VP, Simons AM, Iwasaki H, Gai D, Simmons DT, Chen J. p53 blocks RuvAB promoted branch migration and modulates resolution of Holliday junctions by RuvC. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:1023–32. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulet A, Buisson R, Faivre-Moskalenko C, et al. TRF2 promotes, remodels and protects telomeric Holliday junctions. EMBO J. 2009;28:641–51. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeiri M, Horie K, Takahashi D, et al. Involvement of DNA binding domain in the cellular stability and importin affinity of NF-κB component RelB. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:3053–9. doi: 10.1039/c2ob07104e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May MJ, Ghosh S. Signal transduction through NF-kappa B. Immunol Today. 1998;19:80–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sha WC. Regulation of immune responses by NF-kappa B/Rel transcription factor. J Exp Med. 1998;187:143–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma RK, Otsuka M, Pande V, Inoue J, João Ramos M. Evans Blue is an inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB)-DNA binding. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:6123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umezawa K. Possible role of peritoneal NF-κB in peripheral inflammation and cancer: lessons from the inhibitor DHMEQ. Biomed Pharmacother. 2011;65:252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto M, Horie R, Takeiri M, Kozawa I, Umezawa K. Inactivation of NF-kappaB components by covalent binding of (-)-dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin to specific cysteine residues. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5780–8. doi: 10.1021/jm8006245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panyutin IG, Hsieh P. Formation of a single base mismatch impedes spontaneous DNA branch migration. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:413–24. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karin M. NF-kappaB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000141. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baud V, Karin M. Is NF-kappaB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]