Abstract

Background

Carpal tunnel syndrome is by far the most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome, affecting approximately one in every six adults to a greater or lesser extent. Splitting the flexor retinaculum to treat carpal tunnel syndrome is the second most common specialized surgical procedure in Germany. Cubital tunnel syndrome is rarer by a factor of 13, and the other compression syndromes are rarer still.

Methods

This review is based on publications retrieved by a selective literature search of PubMed and the Cochrane Library, along with current guidelines and the authors’ clinical and scientific experience.

Results

Randomized controlled trials have shown, with a high level of evidence, that the surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome yields very good results regardless of the particular technique used, as long as the diagnosis and the indication for surgery are well established by the electrophysiologic and radiological findings and the operation is properly performed. The success rates of open surgery, and the single-portal and dual-portal endoscopic methods are 91.6%, 93.4% and 92.5%, respectively. When performed by experienced hands, all these procedures have complication rates below 1%. The surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome has a comparably low complication rate, but worse results overall. Neuro-ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (neuro-MRI) are increasingly being used to complement the diagnostic findings of electrophysiologic studies.

Conclusion

Evidence-based diagnostic methods and treatment recommendations are now available for the two most common peripheral nerve compression syndromes. Further controlled trials are needed for most of the rarer syndromes, especially the controversial ones.

Peripheral nerve compression syndromes involve chronic irritation and pressure lesions where nerves pass through anatomical bottlenecks and fibro-osseous canals. The characteristic tunnel syndromes are distinct from acute pressure injuries to a nerve caused by an external compression or blow at a site where a nerve courses superficially over a bony prominence, and from nerve stretching injuries across joints, although mixed injuries also arise. The main clinical manifestations of nerve compression syndromes are paresthesiae, sensory impairment, and paresis (1). The diagnosis is established by the history and physical examination, along with the findings of electrophysiologic studies and imaging (1). Nerve compression syndromes are not life-threatening and generally not disabling, yet they are nonetheless very disturbing for the affected patients.

Definition.

Peripheral nerve compression syndromes involve chronic irritation and pressure lesions where nerves pass through anatomical bottlenecks and fibro-osseous canals.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is by far the most common and most important peripheral nerve compression syndrome. It can generally be diagnosed from the history and physical examination alone on the basis of its typical symptoms and signs. Nonetheless, in our experience, it is often misdiagnosed as a C7 syndrome or as a “circulatory disturbance” such as Raynaud’s disease. Cubital tunnel syndrome, also called ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, is the second most common peripheral nerve syndrome; it is 13 times rarer than carpal tunnel syndrome (2). It was once commonly called “sulcus ulnaris syndrome,” especially in the German-speaking countries, but this designation has been dropped because it described the site of the lesion too imprecisely and seemed to imply a justification for invasive transposition procedures that are now only rarely performed. The available S3 guidelines for these two conditions serve as the basis for this review (2, 3). The other compression syndromes are much rarer, and some of them are controversial (Table 1). They are discussed in the second part of this review.

Table 1. Compression syndromes and focal nerve lesions (from [3]).

| Classic / typical compression syndromes | Combined forms (with pressure or stretch lesions) | Controversial and/or very rare compression syndromes | Atypical syndromes / occupational palsies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel syndrome Supinator syndrome Morton’s metatarsalgia Meralgia paresthetica Cheiralgia (Wartenberg syndrome) Symptomatic tarsal tunnel syndrome |

Cubital tunnel syndrome Loge de Guyon syndrome Peroneal nerve compression syndrome |

Pronator / anterior interosseous nerve syndrome Idiopathic tarsal tunnel syndrome Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) Piriformis syndrome Radial tunnel syndrome Pudendal neuralgia Suprascapular nerve compression syndrome |

Intraneural ganglion Compartment syndrome Nerve torsion Nerve lesions in athletes. musicians. etc. |

The topic of peripheral nerve compression syndromes is dealt with in greater depth in a current monograph (3). A book including a thorough discussion of all aspects of carpal tunnel syndrome was published in 2002 (4).

Learning objectives

This review article should enable readers to:

diagnose carpal tunnel syndrome, determine whether surgery is indicated, and know the differences between open and endoscopic surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome;

diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome and know what conservative and surgical treatments are available;

be aware of the neurogenic causes of sensory disturbances and pain in the limbs, particularly in the feet, and their differential diagnosis.

Carpal tunnel syndrome.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is by far the most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome.

Methods

Our search for pertinent literature on the carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes was based on the respective S3 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of these two conditions (2, 3), which are up to date as of 2014 and have been extended to include discussion of the rarer compression syndromes. We searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and guidelines in the Medline (PubMed) database, the Cochrane Library, guideline databases (the homepages of the German specialty societies and organizations [AWMF and ÄZQ]), and the homepages of the following international specialty societies and organizations:

Guideline International Network (GIN),

Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN),

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),

National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC).

Carpal tunnel syndrome

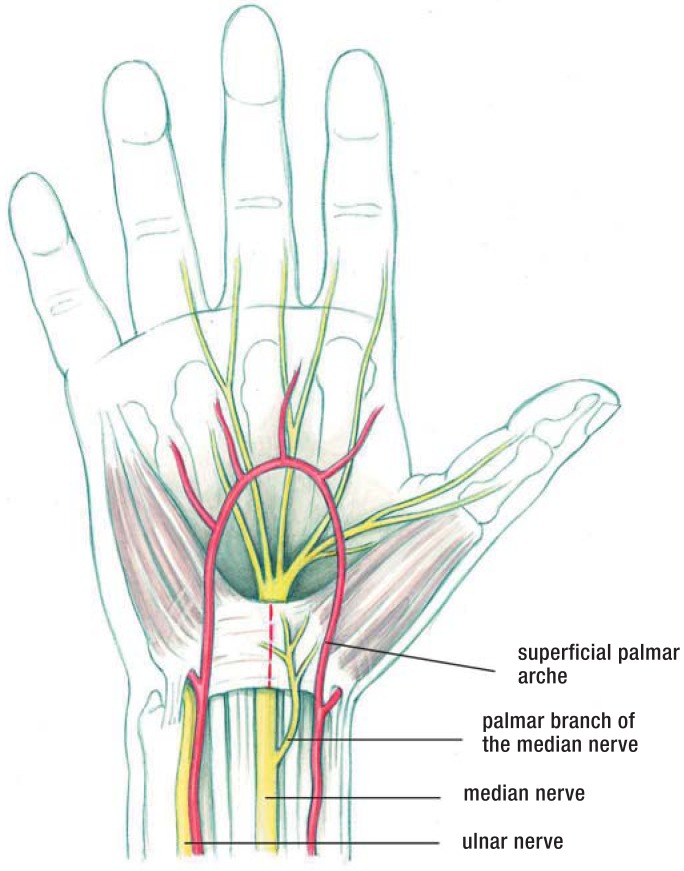

Carpal tunnel syndrome is by far the most common peripheral nerve compression syndrome (3, 4). Some 300 000 operations to treat carpal tunnel syndrome are performed in Germany every year, 90% of them on an outpatient basis (5). Carpal tunnel release is the second most common specialized outpatient surgical procedure in the country, after cataract surgery. Precise case numbers are unavailable, as the German Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (Kassenärztliche Bundesver-einigung, KBV) has not published any newer statistics on the frequency of operations since the introduction of the new Uniform Fee Scale (Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab, EBM). Carpal tunnel syndrome is due to (chronic) median nerve compression in the carpal tunnel (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The carpal tunnel Topographical anatomy of the carpal tunnel and of the course of the median nerve under the flexor retinaculum (the dotted line marks the incision) (3).

Incidence.

The incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome is >3 new cases per 1000 persons per year. Women are affected 3 to 4 times as commonly as men.

Prevalence and incidence

In a study on the adult population of southern Sweden, the prevalence of typical symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome was 14.8%, while that of electrophysiologically verified carpal tunnel syndrome was 4.9% (3). The incidence of the condition was more than 3 new cases per 1000 persons per year (3). Among affected persons, the female-to-male ratio is between three and four to one. Prevalence is associated with age; it is highest in the fifth and sixth decades (4). Carpal tunnel syndrome usually arises bilaterally, but the dominant hand is somewhat more commonly affected, and usually more intensely. In our experience, carpal tunnel syndrome often runs in families (e1). It does not seem to be related to any particular hand position used while typing on a computer keyboard (e2).

Initial symptom.

The initial and main symptom of carpal tunnel syndrome is a painful pins-and-needles sensation in the hand(s), primarily at night (brachialgia paresthetica nocturna).

The symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome often arise in the setting of an episode of tenosynovitis or (perhaps occupational) overuse of the hand, or during pregnancy (3). Carpal tunnel syndrome is recognized as an occupational disorder in persons who perform certain activities involving repetitive flexion and extension of the wrist (e.g., working on a conveyor belt, meat packing, gardening, playing a musical instrument) (5).

The initial and main symptom of carpal tunnel syndrome is a painful pins-and-needles sensation in the hand(s), primarily at night (brachialgia paresthetica nocturna) (1, 3, 4). In more advanced cases, the patient may suffer from numbness of the thumb and middle three fingers and difficulty performing fine manual work. Thenar muscle atrophy is seen only in very advanced cases. The diagnosis can be established by electrophysiology and imaging (Box 1).

Box 1. The diagnostic evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome (1).

-

History

hands “falling asleep”: typical and nearly pathognomonic early symptom

paresthesiae improve or disappear when the hands are “shaken out”

often, both hands are affected; therefore, commonly misdiagnosed as a cervical spine syndrome, cervical myelopathy, or polyneuropathy

persistent numbness and a loss of fine motor control are late symptoms

-

Physical examination

the neurological examination is usually normal in the early stage

clinical tests such as the Phalen (hand flexion) test are unreliable as screening methods for early median nerve compression

-

Neurography

distal motor latency of median nerve >4.2 ms (distance, 7 cm); recommended as a standard measurement because of its high specificity

prolongation of distal motor latency of median nerve compared to ulnar nerve when measured from the 2nd interdigital space, >0.4 ms

sensory nerve conduction velocity (NCV) of the median nerve lower than that of ulnar nerve by more than 8 m/s (most sensitive method) (sensory neurography)

-

Imaging

demonstration of a pseudoneuroma proximal to the site of stenosis as increased cross-sectional area in a high-resolution neuro-ultrasonogram

obtain an MRI if a tumor is suspected

Physical examination involves a search for sensory and motor deficits, as well as two clinical screening tests—the Hoffman–Tinel sign and the Phalen test. Even if the history and physical findings are entirely typical of carpal tunnel syndrome, an electrophysiologic study should be performed to confirm the diagnosis definitively and to provide a baseline for follow-up studies.

Imaging studies—high-resolution neuro-ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging—are now coming into more common use but are not yet the diagnostic methods of first choice. A meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials of these imaging methods yielded overall figures of 77.6% sensitivity and 86.8% specificity (6); in comparison, sensory neurography is 89% sensitive and 98% specific (7). A current evidence-based guideline includes a recommendation for imaging studies as a useful complement to electrodiagnostic studies, particularly for the demonstration of structural changes at the wrist (8).

The main differential diagnoses of carpal tunnel syndrome are C7 syndrome (occasionally, C6 syndrome) and polyneuropathy. The following criteria suggest that a radicular syndrome is present:

the paresthesiae cannot be “shaken out”;

they extend beyond the median nerve distribution;

they are present more or less continuously and are made worse by head movement, coughing, and Valsalva maneuvers.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is sometimes seen in combination with radiculopathy or diabetic neuropathy. Carpal tunnel syndrome is more common in persons with diabetic neuropathy (30%) than in persons without it (14%) (9).

Conservative treatment.

In the early stage of the condition, nocturnal splinting of the wrist and local corticoid infiltration can be recommended.

Treatment

Carpal tunnel syndrome needs to be treated when its typical manifestations are present frequently or persistently and are severe enough to impair the patient’s quality of life. On the other hand, a positive electrophysiologic finding without any corresponding symptoms requires no treatment.

Conservative treatment—In the early stage of the condition, nocturnal splinting of the wrist and local corticoid infiltration can be recommended as treatments whose efficacy has been documented in prospective randomized trials (10, e3). Splinting has been found effective over the long term; corticoid infiltration provides relief for four weeks at most (3). There is no evidence that treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs brings any significant lasting benefit (3).

Therapeutic ultrasound application, exercises, and mobilization techniques (including yoga) are only marginally superior to placebo (e3– e5) and cannot be recommended as treatment options.

The decision when to terminate conservative treatment and proceed to surgery largely depends on the patient’s degree of suffering, rather than on any objective finding. In general, surgery should be performed before a persistent neurologic deficit arises.

Surgical treatment—The following are indications for surgery:

persistent sensory impairment;

intractable nocturnal pain and paresthesiae that keep the patient awake at night.

Multiple randomized controlled trials have documented the superiority of surgery (both open and endoscopic) to conservative treatment, especially with respect to long-term results (11– 15). Surgery must involve the complete splitting of the flexor retinaculum. The operation is now performed on an outpatient basis in nearly all cases; it can also be performed during pregnancy or on a patient who is very old, diabetic, or undergoing dialysis for end-stage renal failure (3).

The available surgical techniques are summarized in Table 2. The simplest and most common treatment, which is also the treatment of choice, is open splitting of the flexor retinaculum.

Table 2. Surgical methods of retinaculum splitting (from [3]).

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open retinaculum splitting (normal incision. 3–4 cm) |

Simple. inexpensive. safe | Larger scar than other methods | Standard method |

| Open retinaculum splitting (mini-incision. ca. 2 cm) |

Smaller scar; possible earlier return to full wrist movement | Risk of incomplete retinaculum splitting and of nerve injury | An alternative to the standard method |

| Single-portal endoscopy (Agee method) |

The pistol-like apparatus is easy to manipulate (one-hand technique) | Costly; special training needed (learning curve) because of the (low) risk of neural and vascular injury | No clear advantage over the standard open methods |

| Dual-portal endoscopy (Chow method) |

Good control of the knife assures that the cut is in the intended direction; cheaper than single-portal technique | Special training needed (learning curve) because of the risk of injury to the common digital nerve | No clear advantage over the standard open methods |

| Semi-open. endoscopically assisted techniques (Preissler. Krishnan. Hoffmann. and others) | Relatively easy to learn. incision somewhat smaller than with the standard open methods | No particular disadvantages | No clear advantage. not widely used. application depends on the surgeon’s personal experience |

Ineffective treatments.

Therapeutic ultrasound application, exercises, and mobilization techniques (including yoga) are only marginally superior to placebo and cannot be recommended as treatment options.

Minimally invasive techniques are currently just as safe as open surgery when performed in experienced hands (e6) and yield comparable results, as has been confirmed in comparative randomized trials (12).

The surgical treatment of choice.

The simplest and most common surgical treatment, which is also the treatment of choice, is open splitting of the flexor retinaculum.

The most commonly used endoscopic instrumentation systems are the single-portal Agee system and the dual-portal Chow system. Endoscopically assisted splitting of the flexor retinaculum is performed with an instrument resembling a pistol (the Agee system) or with various knives introduced through guide tubes (the Chow system). Endoscopic carpal tunnel release has a longer learning curve than the open procedure; the surgeon must be adequately trained in endoscopic technique (16). According to a current meta-analysis of pertinent publications, most of which contain relatively low-level evidence (17), endoscopic carpal tunnel release has the same complication rate as open surgery but is associated with an earlier recovery of hand strength and a more rapid return to work.

Patients should perform functional exercises beginning in the first few days after surgery. On the other hand, patients who have undergone surgery without any complications do not need postoperative rehabilitation measures such as wrist orthoses, cold therapy, laser therapy, multimodal hand rehabilitation, electrotherapy, or scar desensitization. There is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of any of these treatments (18).

Timely surgery yields very good results, with documented success rates as follows:

open surgery, 91.6%;

single-portal endoscopic surgery, 93.4%;

dual-portal endoscopic surgery, 92.5%.

The success rates of surgery are.

open surgery, 91.6%

single-portal endoscopic surgery, 93.4%

dual-portal endoscopic surgery, 92.5%

Elderly patients.

Surgery is beneficial even in advanced cases with sensory impairment and muscle atrophy, and even in elderly patients.

The complication rate in experienced hands is less than 1% (4), over both the short and the long term (4, e6). Surgery is beneficial even in advanced cases with sensory impairment and muscle atrophy, and even in elderly patients (1); the pain and sensory impairment tend to improve, but the muscle atrophy is generally irreversible (1, 4). True recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome after initially effective treatment is rare. In our experience, true recurrence accounted for only 27% of reoperations and was usually seen in dialysis patients (e7).

Improper surgical technique and poor intraoperative exposure may lead to incomplete splitting of the retinaculum and, in turn, to persistent or progressive symptoms that will necessitate a second, corrective surgical procedure (e7, e8).

Cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar neuropathy at the elbow)

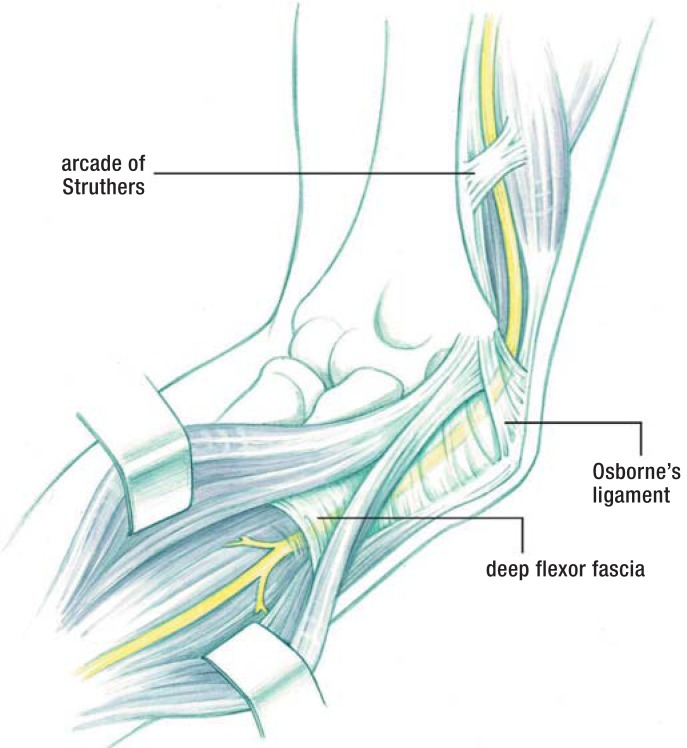

Cubital tunnel syndrome involves compression and irritation of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. It is the second most common nerve compression syndrome and was previously called the sulcus ulnaris syndrome. Neurologists know it as ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The most common site of ulnar nerve compression, where the nerve passes through the cubital tunnel under Osborne’s ligament (3)

Cubital tunnel syndrome involves compression in the cubital tunnel under Osborne’s ligament, often with a contributory component from nerve stretching. It is classified as either primary (idiopathic), including anatomical variants such as ulnar nerve subluxation or an epitrochleo-anconeus muscle, or secondary (symptomatic), including delayed ulnar paresis due to trauma or elbow arthrosis. Secondary cubital tunnel syndrome can also be caused by extraneural or, less commonly, intraneural masses, such as a lipoma or ganglion.

The incidence of cubital tunnel syndrome is 24.7 cases per 100 000 persons per year, which is one-thirteenth that of carpal tunnel syndrome. It is roughly twice as common in men as in women (2). In our experience, the left side is affected almost three times as often as the right, making a further contrast to carpal tunnel syndrome (3, 19) (Box 2). The most common differential diagnoses are an acute pressure-related ulnar nerve palsy after prolonged lying on, or propping oneself up with, the elbow, and acute C8 or T1 radiculopathy due to an irritative or compressive lesion.

Box 2. The diagnostic evaluation of cubital tunnel syndrome (3).

-

History

onset often acute, with numbness or paresthesiae of the 4th and 5th fingers

aching pain in the forearm

atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, often not noticed by the patient

delayed paresis after old elbow joint injury

-

Physical examination

hypesthesia of the ulnar 1 1/2 digits, the ulnar side of the dorsum of the hand, and the hypothenar eminence

positive Froment sign

incomplete or absent adduction of the little finger

tenderness and (often) thickening of the ulnar nerve at the elbow / in the sulcus ulnaris

less commonly, subluxation of the ulnar nerve

atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand innervated by the ulnar nerve, with abnormal claw posture of the 4th and 5th fingers

-

Neurography

lowering of the motor nerve conduction velocity in the elbow segment of the ulnar nerve by more than 16 m/s compared to its forearm segment

significantly lowered amplitude (by at least 40%) of the motor response potential after stimulation proximal to the cubital tunnel, compared to stimulation distal to it

prolonged proximal latency (can be followed longitudinally over the patient’s further course)

-

Imaging

with high-resolution neuro-ultrasonography, demonstration of changes in the size and position of the ulnar nerve at the elbow (also of changes in the echo texture of the nerve)

magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) enables the visualization of structural changes of the ulnar nerve and its environment

Treatment

Mild cases with a recent history can be treated conservatively at first. Nocturnal elbow splinting can markedly improve symptoms. According to a recent clinical study, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type or duration of splinting (e9). Surgery should be performed before the development of muscle atrophy, which is largely irreversible (2).

Cubital tunnel syndrome.

Cubital tunnel syndrome involves compression or irritation of the ulnar nerve at the elbow.

Differential diagnosis.

The most common differential diagnoses are an acute pressure-related ulnar nerve palsy after prolonged lying on, or propping oneself up with, the elbow, and acute C8 or T1 radiculopathy due to an irritative or compressive lesion.

Surgery is indicated in case of (2, 19):

progressive symptoms,

sensorimotor deficits,

lack of clinical and electroneurographic improvement, or

worsening of the objective findings on follow-up several weeks after the initial visit.

Surgical treatment—A variety of surgical methods can be used to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. There has been a paradigm shift over the past decade: according to representative statistics from the USA, the percentage of treatments by nerve transposition has declined from 49% to 38%, while the overall number of surgical procedures has increased by 47% (20). The method of choice is a simple decompression in which the cubital tunnel retinaculum is completely opened in an open surgical procedure through an incision measuring 4 to 6 cm in length (19). Endoscopically assisted decompression is now being increasingly performed. The initial findings in a prospective, blinded trial have not revealed any clear superiority of endoscopy over open surgery (personal communication from Prof. Schroeder, Neurosurgery, Greifswald). The long-term results of anterior transposition (63.1 months of follow-up) are identical to those of decompression (52 months of follow-up) (21). Primary subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve, perhaps accompanied by a partial epicondylectomy, should be considered or preferred in cases with marked anatomical changes in the elbow joint (2) (Table 3).

Table 3. Advantages and disadvantages of surgical methods of treating cubital tunnel syndrome (from [3]).

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open decompression | Simple technique. low risk | Note exceptions | Now the standard method for most cases. including with luxation and subluxation |

| Endoscopically assisted (in situ) decompression | Small incision. low risk. possible over a long distance | Occasionally. subcutaneous hematoma in a wide area; rarely. nerve injury | Competes with the open method |

| Subcutaneous (or submuscular) transposition | Indicated in cases of cubitus valgus and severe post-traumatic conditions | Endangerment of blood supply. operative risks (kinking of the nerve) | Requires extensive operative experience |

| Epicondylectomy (with decompression and/or transposition). partial/minimal epicondylectomy | Less traumatic than deep submuscular transposition | Risk of joint instability; this risk is lower if the epicondylectomy is only partial or minimal | Less commonly used in the German-speaking countries than in the USA and elsewhere |

Surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome.

The method of choice is a simple decompression in which the cubital tunnel retinaculum is completely opened in an open or endoscopic surgical procedure.

Results

Multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews have not revealed any statistically significant difference between the outcomes of simple decompression and anterior transposition (whether subcutaneous or submuscular) (2). The transposition procedures had more frequent complications.

For milder cases, the findings of a randomized controlled trial suggest that conservative treatment is best, with avoidance of unfavorable arm positions and movements (22, 23).

Minimal medial epicondylectomy is an alternative to subcutaneous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve (e10). No predictive factors for the success of the latter procedure could be identified in either of the two studies in which this was tried (24, 25). The second study (25) concerned painful cubital tunnel syndrome.

Overall, the results of surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome are not as good as those of surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome (23). Muscle atrophy of more than one year’s duration is generally only partly reversible, if at all. The rate of recurrence of cubital tunnel syndrome after endoscopic or open decompression is 12.2% (e11).

Rarer and controversial compression syndromes

An overview of these compression syndromes, which affect the upper and the lower limbs, is found in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4. Synopsis of the rarer compression syndromes and neuropathies of the shoulder girdle and the upper limb.

| Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) | Suprascapuluar nerve syndrome | Supinator tunnel syndrome | Pronator teres /_anterior interosseous nerve syndrome | Wartenberg syndrome (cheiralgia) | Loge de Guyon syn- drome (distal ulnar nerve compression) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause | Anomalies (including fibromuscular) of the upper thoracic aperture. cervical rib | Ganglia. normal anatomic variants. traction injuries in athletes | Compression of the deep radial nerve under the arcade of Frohse. lipomas. and other mass lesions | Possibly inflammatory in lesions of the anterior interossous nerve or nerve fascicle torsion | Idiopathic compression of the superficial radial nerve | Subacute compression (handlebar palsy. crutch palsy). ganglia |

| Symptoms | Pain and paresthesiae. particularly when carrying heavy loads and working above the head | Shoulder pain. weakness of external rotation of the arm | Weakness of finger extensors (DD ruptured extensor tendon); if painful. DD tennis elbow | Uncharacteristic in pronator syndrome; in AIN lesion. weakness of thumb and of flexion of the distal phalanx of the index finger | Pain and paresthesiae in the thumb and dorsum of the hand | activity-induced pain (more common if a ganglion is the underlying lesion). weak key grip |

| Physical findings | Hoffmann–Tinel sign in the supraclavicular fossa. sometimes weakenss and atrophy of the small muscles of the hand | Atrophy of the supra- and infraspinatus muscles | Weakness of finger extensors and of ulnar (but not radial) wrist extensor; no sensory deficit | Pathological pinch grip | Positive Finkelstein test. hypesthesia may be absent | Froment sign. atrophy of adductor pollicis; no hypesthesia in exclusive involvement of the deep branch of the ulnar nerve |

| Electrophysiology | For the exclusion of CTS. CUTS. etc. | EMG | EMG. neurography of the deep radial nerve | EMG | Sensory neurography | Sensory and motor neurography. EMG |

| Imaging | Magnetic resonance neurography of the brachial plexus; x-ray for cervical rib | MRI to demonstrate ganglia | Demonstration of compression and mass witn US and MRI | Potential demonstration of fascicle torsion by MRN or neuro-ultrasonography | Ultrasound | Ultrasound |

| Treatment | Patient exercises; surgery not recommended. as the evidence base is inadequate | Infiltration to treat pain. surgery to remove ganglia; no RCTs available | Usually surgical; no RCTs available | Controversial; no RCTs | Usually conservative. no RCTs | From expectant to surgical; no RCTs |

AIN. anterior interosseous nerve; CTS. carpal tunnel syndrome; CUTS. cubital tunnel syndrome; DD. differential diagnosis; EMG. electromyography; MRI. magnetic resonance imaging; _MRN. magnetic resonance neurography; RCT. randomized and controlled trial

Table 5. Synopsis of rarer peripheral nerve compression syndromes of the lower limb.

| Meralgia paresthetica | (Posterior) tarsal tunnel syndrome | Morton’s metatarsalgia | Peroneal nerve compression | Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause | Compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve under the inguinal ligament | Compression of the tibial nerve or plantar nerves in the tarsal tunnel or distally; unequivocal only with a tumor | Compression of digital nerves between metatarsal heads. accompanying bursitis | Unknown in most cases; work in squatting position. extra- and intraneural ganglia | Compression of the deep peroneal nerve in the dorsum of the foot; cause often unknown; shoes |

| Symptoms | Hypesthesia and dysesthesia on the ventrolateral aspect of the thigh | Paresthesia. dysesthesia. and numbness of the sole and toes | “I can’t wear tightly fitting shoes any more” | Pain radiating into the leg. weakness of dorsiflexion | Pain in the dorsum of the foot |

| Physical findings | Tenderness medial to the anterior superior iliac spine | Local tenderness and Hoffmann–Tinel sign | Tenderness in the interdigital space. usually D3/4 (Mulder test); in some cases. hypesthesia of the adjacent sides of toes | Weakness of tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum muscles. tenderness over fibular head. hypesthetic dorsum of foot | Tenderness in the dorsum of the foot. atrophy of the extensor digitorum brevis. hypesthesia on the dorsum of the hallux |

| Electrophysiology | Sensory neurography optional | Not definitive (Patel 2005); sensory NCV in a comparison of the two sides | Not applicable | Neurography. EMG | Neurography. EMG |

| Imaging | Ultrasonography difficult | Demonstration of extra- and intraneural mass lesions in the symptomatic form | Ultrasonography as method of 1st choice. otherwise MRI | Ultrasonography. demonstration of a ganglion | Unknown |

| Treatment | Initially conservative (corticoid injection). surgical in case of intractability; no RCTs available | Unclear for idiopathic origin; generally operative when caused by a mass; no RCTs available | Generally operative by a plantar or dorsal approach; no RCTs | Expectant or operative (ganglion); no RCTs | Expectant or operative; no RCTs |

RCT. randomized and controlled trial; NCV. nerve conduction velocity; EMG. electromyography

Treatment outcomes.

Multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews have not revealed any statistically significant difference between the outcomes of simple decompression and anterior transposition (whether subcutaneous or submuscular).

What is known about the rarer compression syndromes, and what remains uncertain?

Here we will briefly characterize and assess, as well as we can, this mixed group of focal compressive nerve lesions, some of which are still inadequately explained and controversial (see also Table 1).

Supinator tunnel syndrome.

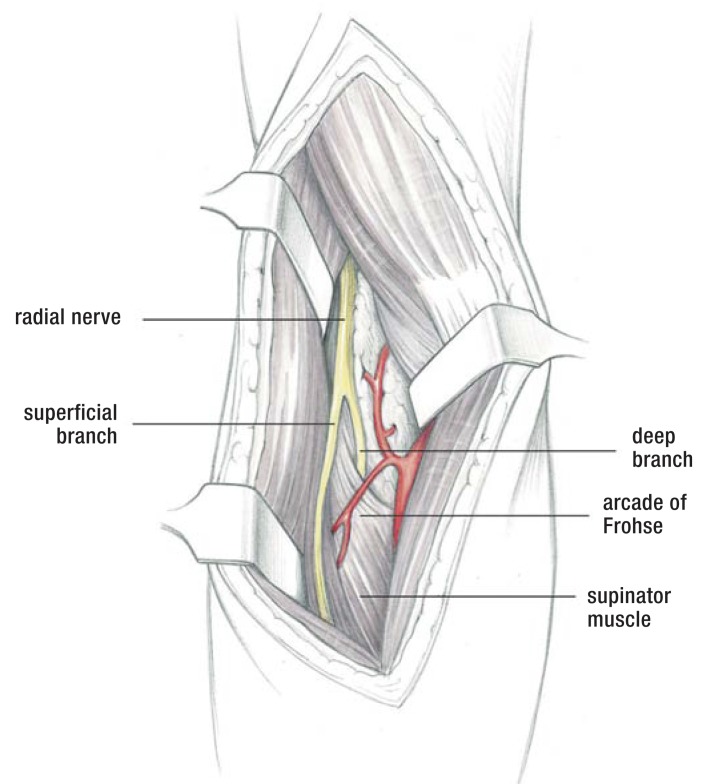

In the supinator tunnel syndrome (syndrome of the posterior interosseous nerve, PIN), the deep radial nerve is compressed under the arcade of Frohse.

In the supinator tunnel syndrome (syndrome of the posterior interosseous nerve, PIN), the deep radial nerve is compressed under the arcade of Frohse. A systematic review of the treatment of this condition revealed that controlled clinical trials are scarce, but two observational studies provide evidence that surgical decompression of the PIN may be effective in cases of idiopathic compression (26). A space-occupying lesion such as a lipoma or ganglion that causes symptomatic compression of the PIN is a clear indication for surgery. This syndrome is associated with weakness and is not to be confused with the so-called painful supinator tunnel syndrome (also called “tennis elbow”). Studies to date have not revealed a neurogenic origin for the pain in the latter condition, which is its only symptom.

Meralgia paraesthetica.

Meralgia paresthetica is pain due to compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve under the inguinal ligament. Only weak evidence exists to support any treatment recommendation because of a lack of randomized controlled trials.

Meralgia paresthetica is pain due to compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve under the inguinal ligament. Only weak evidence exists to support any treatment recommendation because of a lack of randomized controlled trials. In the best observational studies performed to date, similar results were observed after treatment with injections, after surgical treatment (by decompression or nerve transection), and without any treatment (27).

Suprascapular nerve syndrome arises both in an idiopathic form, mainly in high-performance athletes (e.g., volleyball and basketball players), and in a symptomatic form, caused by a ganglion. The indication for surgery is intractable pain along with atrophy of the supra- and infraspinatus muscles, if the presence of a ganglion is confirmed by an imaging study. The surgical treatment can be either open or endoscopic (28, e12). No controlled trials of treatment have been performed to date.

Thoracic outlet syndrome.

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is one of the more controversial nerve compression syndromes. The diagnosis is hard to make in patients who have pain but no clear-cut neurologic deficit (so-called atypical TOS).

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is one of the more controversial nerve compression syndromes. The diagnosis is hard to make in patients who have pain but no clear-cut neurologic deficit (so-called atypical TOS). It may be that magnetic resonance neurography will bring greater diagnostic certainty in the future (29). A randomized double-blind trial revealed no improvement of pain or paresthesiae after conservative treatments such as botulinum toxin injections in the anterior and medial scalene muscles (30). In the absence of evidence-based criteria for surgical indications, the decision to operate can only be made on a case-by-case basis (31).

Wartenberg syndrome.

Wartenberg syndrome is a rare condition in which compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve causes pain and paresthesiae on the radial side of the dorsum of the hand, and in the thumb.

Wartenberg syndrome, also called cheiralgia paresthetica, is a rare condition in which compression of the superficial branch of the radial nerve causes pain and paresthesiae on the radial side of the dorsum of the hand, and in the thumb (3). Sensory deficits are rare, and neurography is reliable only if there is a pathological finding. There have been only sporadic case reports of ultrasonographic findings and treatment outcomes, and there have not been any controlled clinical trials on which to base decisions about surgery. External pressure lesions of the cutaneous nerve are more common and are often caused by bracelets with sharp edges.

The symptoms of loge de Guyon syndrome and of distal ulnar nerve compression at the wrist vary depending on the site of the lesion. Isolated compression of the deep branch is more common. It is characterized by a positive Froment sign and by atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous muscle, without any accompanying sensory deficit. It is commonly caused by a ganglion or by external pressure (thus the term “cyclist’s palsy” or “handlebar palsy”). Because of the rarity of this condition, no controlled therapeutic trials have been performed. A ganglion causing progressive neurologic symptoms should be surgically removed. Pressure lesions usually improve spontaneously.

Pronator syndrome, caused by compression of the median nerve just below the elbow, and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, caused by compression of this nerve, are rare and controversial conditions (32). There are no large cases series or controlled therapeutic trials for either. These entities clinically resemble Kiloh-Nevin syndrome, which is presumed to be a form of neuritis. They have been provisionally attributed to fascicle torsion, of uncertain pathogenetic significance, in the main stem of the median nerve and proximal to the origin of the anterior interosseous nerve (33). According to a recently published study, these entities may be related to immunological mononeuropathies such as multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) (34).

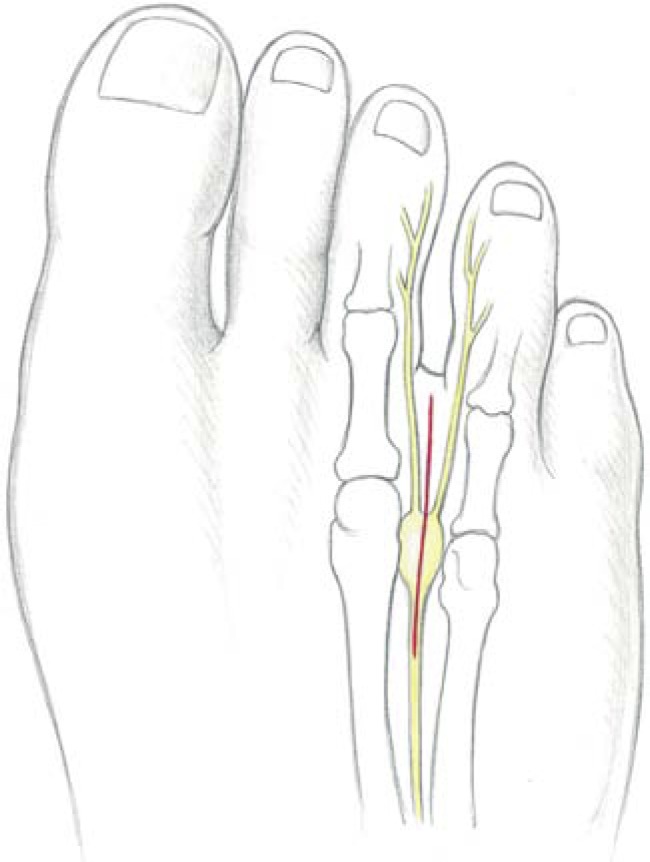

Morton’s metatarsalgia.

Morton’s metatarsalgia is due to compression of the interdigital nerves by displacement of the neurovascular bundle, usually in the space between the third and fourth toes, and usually with accompanying bursitis.

Morton’s metatarsalgia is due to compression of the interdigital nerves by displacement of the neurovascular bundle, usually in the space between the third and fourth toes, and usually with accompanying bursitis. A “spot diagnosis” can often be made on clinical grounds alone if the patient has typical symptoms (“I can’t wear tightly fitting shoes any more”) and a positive Mulder sign. Local infiltration of alcohol has been found ineffective (e13), while local corticoid infiltration has been found effective, but only for a limited time (35). Success rates of 70% to 90% have been reported for surgical excision of the pseudoneuroma through a dorsal (or plantar) approach (36, e14, e15).

Tarsal tunnel syndrome is a controversial entity, at least in cases that cannot be attributed to a mass lesion (ganglion, schwannoma) or prior trauma. The very rare idiopathic type is overdiagnosed (37); this diagnosis is particularly inappropriate when it is not supported by either electrophysiology or imaging. A mass lesion is the only clear indication for surgery. In other cases, no evidence-based treatment recommendation can be made.

Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome, i.e., idiopathic compression of the distal portion of the deep peroneal nerve under the extensor retinaculum, has been only rarely described and remains poorly diagnosed (e16). Proximal, focal peroneal neuropathy near the fibular head is more common; it is often due to external pressure (e.g., faulty positioning for surgery) or a stretch injury. Surgery for a peroneal nerve palsy is generally indicated where ultrasound reveals an intra- or extraneural ganglion cyst originating from the tibiofibular joint (38).

Multiple decompressions of the tibial nerve and its branches in the tarsal tunnels, and of the peroneal nerve at the knee, were recommended at one time as a putative means of preventing ulcers in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy. It was concluded in a systematic review (39) that there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials, or from well-documented prospective studies, to support the efficacy of this treatment. Further studies have been published since then, some of them with large numbers of cases (e17– e19); nevertheless, the benefit of decompressive surgery of this type cannot be definitively assessed at present.

Piriformis syndrome, another controversial compression syndrome, is said to be due to compression of the sciatic nerve in the infrapiriform foramen. There is no validated diagnostic or therapeutic procedure for piriformis syndrome (e20). Attempts have been made to treat it with local infiltration of local anesthetic agents, corticoids, and botulinum toxin, usually under imaging guidance (computed tomography or ultrasound) (e21, e22).

Controversial compression syndromes.

Piriformis syndrome is a controversial compression syndrome said to be due to compression of the sciatic nerve in the infrapiriform foramen. There is no validated diagnostic or therapeutic procedure for piriformis syndrome.

Compression syndromes of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are rare. They can arise as the result of a traumatic hematoma, or else iatrogenically after inguinal hernia repair, urologic procedures, laparoscopy, vascular puncture, or iliac crest biopsy.

Diagnostic and therapeutic nerve blocks are ineffective in the management of pain after inguinal hernia repair (e23).

The clinical experience with pudendal neuralgia as a putative cause of pain in the perineal region is similarly problematic. Electrophysiologic studies have only limited sensitivity and specificity for this condition, which is diagnosed on clinical grounds (e24). Surgical decompression has been reported to be of limited efficacy in two-thirds of cases (e25).

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

This CME unit can be accessed until 29 March 2015 and will be inactivated on 30 March 2015.

Earlier CME units can be accessed until the dates indicated:

“The Diagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease” (issue 49/2014) until 1 March 2015

“Chronic and Treatment Resistant Depression” (issue 45/14) until 1 February 2015

“Physical Examination in Child Sexual Abuse” (issue 41/14) until 4 January 2015

Please answer the following questions to participate in our Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

What is the most sensitive test for the early diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome?

distal motor latency

sensory neurography

electromyography

neuro-ultrasonography

neuro-MRI

Question 2

What is absolutely essential in the surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome?

The motor branch must be exposed.

An epineurotomy must be performed.

The retinaculum must be completely split.

The wrist must be immobilized in a cast.

A synovectomy must be performed.

Question 3

What syndrome has a positive Phalen test?

loge de Guyon syndrome

pronator syndrome

carpal tunnel syndrome

Wartenberg syndrome

Morton syndrome

Question 4

What is the typical site of ulnar nerve compression?

in the loge de Guyon

under Osborne’s ligament

under the arcade of Struthers

in the sulcus ulnaris

in the supinator tunnel

Question 5

What is the most likely diagnosis if a male patient complains of painful “falling asleep” of the hands?

syringomyelia

impaired circulation

cervical spondylosis

carpal tunnel syndrome

peripheral neuropathy

Question 6

What condition is associated with isolated atrophy of the first dorsal interosseus muscle without any sensory disturbance?

C8 radiculopathy

distal ulnar nerve compression

neural muscular atrophy

posterior interosseous nerve syndrome

thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS)

Question 7

Which of the following is typical in supinator tunnel syndrome?

arm pain at night

sensory impairment on the dorsum of the hand and thumb

weak wrist extension

weak finger and thumb extension

loss of the brachioradialis reflex

Question 8

What diagnosis is most likely when a female patient complains that she can no longer wear tightly fitting shoes?

intermittent claudication

sciatica

Morton’s metatarsalgia

flat feet

tarsal tunnel syndrome

Question 9

What syndrome characteristically manifests weakness of key grip?

anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome

supinator tunnel syndrome

Wartenberg syndrome

loge de Guyon syndrome

Question 10

What is the usual cause of Morton’s metatarsalgia?

interdigital nerve compression by displacement of the neurovascular bundle

compression of the deep radial nerve under the arcade of Frohse

compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve under the inguinal ligament

subacute compression by a ganglion

a hereditary normal anatomical variant

eFigure 1.

Supinator tunnel syndrome. The deep branch of the radial nerve is usually compressed under the arcade of Frohse (3)

eFigure 2.

Morton’s metatarsalgia. A pseudoneuroma develops between the 3rd and 4th (and between the 2nd and 3rd) metatarsal heads (3)

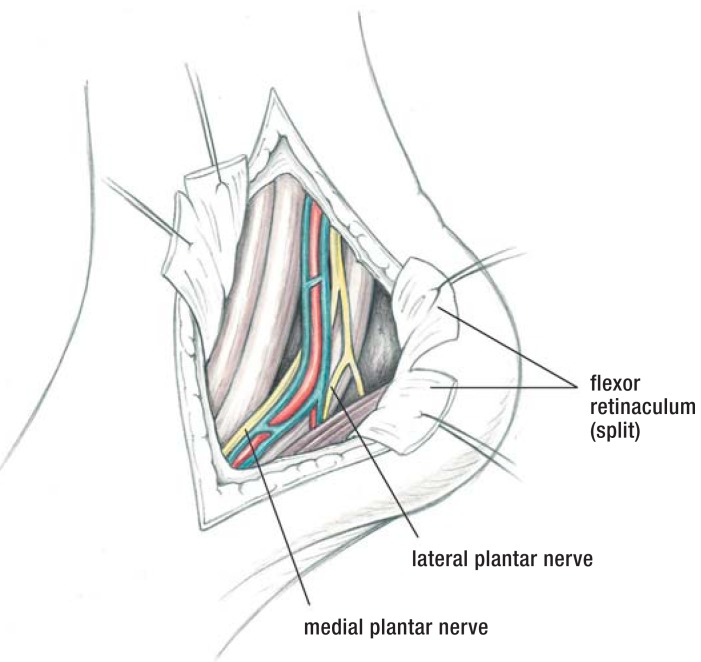

eFigure 3.

flexor retinaculum (split)

lateral plantar nerve

medial plantar nerve

Exposure of the neurovascular bundle after opening the posterior tarsal tunnel (3)

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Assmus H G. Die Kompressionssyndrome des N. medianus. In: Assmus H, Antoniadis G, editors. Nervenkompressionssyndrome. 3rd edition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. pp. 45–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C, et al. Diagnostik und Therapie des Kubitaltunnelsyndroms. AWMF-Leitlinienregister Nr. 005-009. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/005-009l_abgelaufen.pdf. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185287. (last accessed on 11 September 2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C, et al. Diagnostik und Therapie des Karpaltunnelsyndroms. AWMF-Leitlinienregister Nr. 005-003 www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/005-003l_S3_Karpaltunnelsyndrom_Diagnostik_Therapie_2012-06.pdf. (last accessed on 11 September 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum RB, Ochoa JL. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Butterworth Heinemann; 2002. Carpal tunnel syndrome and other disorders of the median nerve. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giersiepen K, Spallek M. Carpal tunnel syndrome as an occupational disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:238–242. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler JR, Gaughan JP, Ilyas AM. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: a metaanalysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1089–1094. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AAEM American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Practice parameter for electrodiagnostic studies in carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:918–922. doi: 10.1002/mus.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright MS, Hobson-Webb LD, Boon AJ, et al. Evidence based guideline: neuromuscular ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:287–293. doi: 10.1002/mus.23389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahrmann A, Zieschang T, Hein G, Oster P. Karpaltunnelsyndrom bei Diabetes mellitus. Med Klin. 2010;105:150–154. doi: 10.1007/s00063-010-1024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall S, Tardif G, Ashworth N. Local steroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001554.pub2. CD001554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huisstede BM, Randsdorp MS, Coert JH, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome Part II: Effectiveness of surgical treatment—a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1005–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholten RJ, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BM, et al. Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003905.pub3. CD003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdugo RJ, Salinas RS, Castillo J, Cea JG. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001552. CD001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Q, MacDermid JC. Is surgical intervention more effective than non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome? A systematic review. J Orthop Res. 2011;6 doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasilidiasis HS, Georgoulas P, Shrier I, et al. Endoscopic release for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008265.pub2. CD008265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AAOS American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Rosemont. 2008. Clinical practice guideline on the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kretschmer T, Antoniadis G, Richter HP, König RW. Avoiding iatrogenic nerve injury in endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2009;20:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters S, Page MJ, Coppieters MW, et al. Rehabilitation following carpal tunnel release. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004158.pub2. CD004158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C, et al. Cubital tunnel syndrome—a review and management guidelines. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2011;72:90–98. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soltani AM, Best MJ, Francis CS, et al. Trends in the surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: an anlysis of the national survey of ambulatory surgery database. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:1551–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keiner D, Gaab MR, Schroeder HW, et al. Comparison of the long-term results of anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve or simple decompression in the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome—a prospective study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009;151:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macadam SA, Bezuhly M, Lefaivre KA. Outcomes measures used to assess results after surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:1482–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caliandro P, La Torrre G, Padua R, et al. Treatment for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006839.pub3. CD006839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Q, MacDermid JC, Santaguida PL, Kyu HH. Predictors of surgical outcomes following anterior transposition of ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1996–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.09.024. e1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinkel WD, Schreuders TA, Koes BW, Huisstede BM. Current evidence for effectiveness of interventions for cubital tunnel syndrome, instability, or bursitis of the elbow: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:1087–1096. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31828b8e7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huisstede BM, Miedema HS, van Opstal T, et al. Interventions for treating the radial tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of observational studies. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil N, Nicotra A, Racovicz W. Treatment for meralgia paraesthetica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004159.pub2. CD004159 und 2012; 12: CD004159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antoniadis G, Richter HP, Rath S, et al. Suprascapular nerve entrapment: experience with 28 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:1020–1025. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumer P, Kele H, Kretschmer T, et al. Thoracic outlet syndrome in 3T MR neurography-fibrous bands causing discernible lesions oft he lower brachial plexus. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:756–761. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finlayson HC, O’Connor RJ, Brasher PM, Travlos A. Botulinum toxin injection for management of thoracic outlet syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Pain. 2011;152:2023–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Povlsen B, Belzberg A, Hansson T, Dorsi M. Treatment for thoracic outlet syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007218.pub2. CD007218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodner CM, Tinsley BA, O’Malley MP. Pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:268–275. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-05-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochi K, Horiuchi Y, Tazaki K, Takayama S, Matsumura T. Fascicular constrictions in patients with spontaneous palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve and the posterior interosseous nerve. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46:19–24. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2011.634558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pham M. MR-Neurographie zur Läsionslokalisation im peripheren Nervensystem. Warum, wann und wie? Nervenarzt. 2014;85:221–237. doi: 10.1007/s00115-013-3951-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson CE, Beggs I, Martin DJ, et al. Methylprednisolone injections for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma: a patient-blinded randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:790–798. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assmus H. Die Morton-Metatarsalgie. Ergebnisse der operativen Behandlung bei 54 Fällen. Nervenarzt. 1994;65:238–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antoniadis G, Scheglmann K. Posterior tarsal tunnel syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztbl Int. 2008;105:776–781. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spinner RJ, Atkinson JLD, Scheithauer BW, et al. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. Clinical series. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:319–329. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.2.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaudry V, Russell J, Belzberg A. Decompression surgery of lower limbs for symmetrical diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006152.pub2. CD006152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dellon AL, Muse VL, Nickerson DS, et al. Prevention of ulceration, amputation, and reduction of hospitalization: outcomes of a prospective multicenter trial of tibial neurolysis in patients with diabetic neuropathy. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28:241–246. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Assmus H. Ist das Karpaltunnelsyndrom erblich? Akt Neurol. 1993;20:138–141. [Google Scholar]

- e2.O’Connor D, Page MJ, Marshall SC, Massy-Westropp N. Ergonomic positioning or equipment for treating carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009600. CD009600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Page MJ, Massy-Westrop N, O’Connor DA, Pitt V. Splinting for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010003. CD010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Page MJ, O’Connor DA, Pitt V, Massy-Westrop N. Exercise and mobilisation interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009899. CD009899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Page MJ, O’Connor DA, Pitt V, Massy-Westrop N. Therapeutic ultrasound for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009601.pub2. CD009601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Haupt WF, Wintzer G, Schop A, Lottgen J, Pawlik G. Long-term results of carpal tunnel decompression. Assessment of 60 cases. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:471–474. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90149-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Assmus H, Dombert T, Staub F. Rezidiv- und Korrektureingriffe beim Karpaltunnelsyndrom. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38:306–311. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Soltani AM, Allan BJ, Best MJ, et al. A sytematic review of the literature on the outcomes of treatment for recurrent and persistent carpal tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconst Surg. 2013;132:114–121. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318290faba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Szabo RM, Kwak C. Natural history and conservative managemant of cubital tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 2007;23:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Capo JT, Jakob G, Maurer RJ. Subcutaneous anterior transposition versus decompression and medial epicondylectomy for the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Orthopedics. 2011;34:713–717. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110922-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Cobb TK, Sterbank PT, Lemke JH. Endoscopic cubital tunnel recurrence rates. Hand. 2010;5:179–183. doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Freehill MT, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Warner JJ. Suprascapular neuropathy. Diagnosis and treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40:72–83. doi: 10.3810/psm.2012.02.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Gurdezi S, White T, Ramesh P. Alcohol injection for Morton’ neuroma: a five-year follow-up. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:1064–1067. doi: 10.1177/1071100713489555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Kasparek M, Schneider W. Surgical treatment of Morton’s neurome: clinical results after open excision. Int Orthop. 2013;37:1857–1861. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Akermark C, Crone H, Skoog A, Weidenhielm L. A prospective randomized controlled trial of primary versus dorsal incisions for operative treatment of primary Morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:1198–1204. doi: 10.1177/1071100713484300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Logullo F, Ganino C, Lupidi F, Perozzi C, Di Bella P, Provinciali L. Anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome: a misunderstood and a misleading entrapment neuropathy. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:773–775. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Zhang W, Li S Zheng X. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of multiple lower extremity nerve decompression in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2013;74:96–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1320029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Valdivia JM, Weinand M, Malconey CT, Jr, et al. Surgical treatment of superimposed, lower extremity, peripheral nerve entrapments with diabetic and idiopathic neuropathy. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70:675–679. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182764fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Nickerson DS, Rader AJ. Low long-term risk of foot ulcer recurrence after nerve decompression in a diabetes neuropathy cohort. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2013;103:380–386. doi: 10.7547/1030380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Miller TA, White KP, Ross DC. The diagnosis and management of piriformis syndrome: myths and facts. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:577–583. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100015298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Masala S, Crusco S, Meschini A, Taglieri A, Calabria E, Simonetti G. Piriformis syndrome: long-term follow-up in patients treated with percutaneous injection of anesthetic and corticosteroid under CT guidance. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Jankovic D, Peng P, van Zundert. A. Brief review: piriformis syndrome: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:1003–1012. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Bischoff JM, Koscielniak-Nielsen ZJ, Kehlet H, Werner MU. Ultrasound-guided ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks for persistent inguinal postherniorrhaphy pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1323–1329. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824d6168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Robert R, Labat JJ, Riant T, Khalfallah M, Hamel O. Neurosurgical treatment of perineal neuralgias. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2007;32:41–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-47423-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Lefaucheur JP, Labat JJ, Amerenco G, et al. What is the place of electroneuromyographic studies in the diagnosis and management of pudendal neuralgia related to entrapment syndrome. Neurophysiol Clin. 2007;37:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]