Abstract

Background

People with psychiatric disorders and their family members have expressed interest in receiving genetic counseling (GC). In February 2012, we opened the first (to our knowledge) specialist psychiatric GC clinic of its kind, for individuals with non-syndromic psychiatric disorders and their families. Prior to GC and at a standard one-month follow-up session, clinical assessment tools are completed, specifically, the GC outcomes scale (GCOS, which measures empowerment, completed by all clients) and the Illness Management Self Efficacy scale (IMSES, completed by those with mental illness).

Methods

Consecutive English-speaking clients attending the clinic between February 1, 2012-January 31, 2013 who were capable of consenting were asked for permission to use their de-identified clinical data for research purposes. Descriptive analyses were conducted to ascertain demographic details of attendees, and paired sample t-tests to assessed changes in GCOS and IMSES scores from pre- to post GC.

Results

Of 143 clients, 7 were unable to consent, and 75/136 (55.1%) consented. Most were female (85.3%), self-referred (76%), and had personal experience of mental illness (65.3%). Mean GCOS and IMSES scores increased significantly after GC (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.011, respectively).

Conclusion

In a naturalistic setting, GC increases empowerment and self-efficacy in this population.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, depression, empowerment, genetic counseling, mental illness, psychiatric disorders, schizophrenia, self-efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric disorders are very common, demonstrated by the facts that schizophrenia and bipolar disorder each affect ~1% of the general population, and ~25% of women and ~10% of men will experience depression at some point in their lives (1, 2). Psychiatric disorders are etiologically complex, in that they typically arise as a result of the combined effects of genetic and environmental factors, and heterogeneous, in that rare genetic variants of large effect and common variants of small effect may all play etiologic roles in different individuals.

Despite advances in psychiatric genetics, there has been little progress in systematically translating this knowledge for people with psychiatric disorders and their families in a thorough and individualized manner. However, it is well established that having an explanation regarding why one developed an illness is so critical to the process of adaptation, that in the absence of being provided with a comprehensible explanation for the cause of illness, affected individuals will develop their own explanatory model (3). Unfortunately these explanations are not necessarily accurate, and can invoke unnecessary feelings of shame and guilt (4). Self Regulation Theory (5) suggests that an awareness of the nature of one’s illness, including an understanding of its causes, is important in determining how one behaviourally responds to that illness (6–8).

As an intervention that is designed to help people “understand and adapt to the medical, psychological and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease” (9), genetic counseling (GC) is ideally suited to helping people with psychiatric disorders and their families to understand the origins of their illness, and therefore perhaps to adapt more successfully. Indeed, research suggests that most individuals with psychiatric disorders would like to receive GC (10, 11), and has shown that shown GC is beneficial both to individuals with serious mental illness and to parents of affected individuals (12–14). However, in a 2009 study, 83% of genetic counselors reported that they rarely or never see patients referred for a primary indication of a psychiatric disorder (15), and a review of our own provincial medical genetics centre revealed only 288 referrals to discuss a personal or family history of schizophrenia over a 40 year period (16). So, on February 1, 2012, we launched what is to our knowledge the world’s first specialist clinical psychiatric GC service of its kind, for individuals with non-syndromic psychiatric disorders and their families (See Box 1).

Box 1. The psychiatric GC clinic.

Context and clinical staff

The psychiatric GC clinic is available to all residents of British Columbia who have a personal or family history of any psychiatric disorder, through self- or healthcare provider referral, and is covered by the British Columbia (BC) Medical Service Plan (mandatory health insurance). A board-certified genetic counselor collects the family history information (via telephone in advance of the GC appointment, whenever possible), and provides the genetic counseling: in-person (in Vancouver or at an outreach location), via telephone, or via telehealth. A clinical geneticist signs all reports and consults regarding possible genetic syndromes, and a psychiatrist provides consultation regarding psychiatric issues. Appointments are provided to family groups or individuals as requested by clients. All clients are contacted by telephone one month after their appointment for a follow up assessment, at which time the option of an additional appointment is presented. Hospital-based professional interpreters are engaged to facilitate communication as appropriate.

Clinical assessment tools

At the beginning of the GC appointment and at the one-month follow-up call, clients complete clinical assessment tools to establish issues for discussion and to assess the client’s current state. Specifically, all clients complete the GC outcomes scale (GCOS, (17)) and those with a personal history of mental illness also complete the Illness Management Self Efficacy scale (IMSES, (18)). These instruments lend themselves well to use as clinical assessment tools – for example, the GCOS contains questions such as: “I feel guilty because I (might have) passed this condition on to my children”, and the IMSES contains items such as: “How confident are you that you can do the different tasks and activities needed to manage your mental illness on your own between visits to your health care provider?” The tools were usually completed by clients themselves (using pencil and paper) prior to GC, and online or via telephone (administered by the counselor) afterwards.

In addition, at the beginning of the GC session (or at the pre-appointment family history gathering telephone call), all clients are asked about their main reason for wanting to attend the appointment. In all cases, responses are detailed in clinic chart notes.

Practice orientation and content overview

The practice orientation of the psychiatric GC clinic values the client-centred approach and acknowledges that GC is neither purely educational, nor purely counseling-based; but rather that it is a hybrid model (19). The information-gathering component of GC entails uncovering the client’s existing explanation for the cause of illness, and eliciting and documenting a detailed psychiatric family history (the genetic counselor is trained/experienced in first -and third-person psychiatric interviewing, this is employed to confirm psychiatric diagnoses in the client, and family members respectively). The information-provision component involves provision of evidence-based information about: 1) factors that have been associated with the development of the indicated condition (genetic and environmental contributions to illness are discussed together, in a holistic fashion), 2) strategies that individuals might use to protect their mental health (e.g., Sleep, exercise, nutrition), and 3) when requested, communicating about risk for family members (e.g., existing or potential children) to develop the indicated condition (20–23). The etiological information provided is broadly applicable to psychiatric disorders, but using visual aids and active encouragement of discussion, questions and interaction to facilitate comprehension, the genetic counselor relates this information to the client’s own family history, their existing explanation for cause of illness, and how illness self-management strategies and psychotropic medications can help to reduce symptoms and/or risk of relapse (20). This information is not neutral, it is in fact “…loaded, creating affective, cognitive and behavioral reactivity” (24) in clients – much of which typically relates to guilt, fear and shame, which the counselor attempts to identify, expose and address in the session. Even when it is established at the beginning of a session that a client’s primary concern is about risk for family members, the counseling typically addresses causes and protective factors first in order to frame and provide context for the figures that may be provided. In some instances, clients are sufficiently reassured by this discussion (it becomes evident that the chance of recurrence is not 100%, for example) that they then decline to discuss specific probabilities. Risk communication typically involves explicitly stated caveats regarding the fact that probabilities may be affected if diagnoses were to change from those reported.

Provision of genetic testing

Importantly, though recent research raises the question of clinical utility of microarray testing for patients who have a personal history of schizophrenia (25), there are currently no clinically recommended genetic tests for idiopathic psychiatric disorders, and in the context of the clinic, it is not currently part of the clinical model. Individuals who are identified (through screening of personal medical and family histories) as potentially having an as yet undiagnosed genetic syndrome are not seen in the context of the specialist clinic that we describe herein. Instead, these clients are referred for evaluation by a clinical geneticist in the main medical genetics program, where genetic testing may be ordered.

In the present study, we present data from the first year of providing this service, including demographic data of clients who attended, and outcomes data in this naturalistic setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedure overview

All eligible clients who attended the psychiatric GC clinic (described in Box 1) between February 1, 2012 and January 31, 2013 were provided with the option of consenting to allow their de-identified clinical data to be used in research. For most clients, this invitation was extended by means of letter and a consent form accompanying their appointment confirmation letter, however, a few of the earliest clients were contacted retrospectively. Individuals were considered eligible for study participation if they were fluent in English and considered able to provide informed consent (e.g. those actively experiencing psychosis were excluded). We reviewed the charts of all those who consented to extract demographic information, and the primary described reason for attending the GC appointment. Participants’ primary reasons for attending were grouped into three categories, which captured all responses: to understand cause of mental illness, to understand ways to protect mental health, and to understand the chances for recurrence of illness among other family members (with sub-classifications regarding the type of relative for whom this information was sought). Participants’ GCOS and ISMES scores prior to (T1) and one month after (T2) GC were analyzed. Institutional Review Board approval was received for this study from BC Children and Women’s Research Ethics Board (H12-00063).

Quantitative Instruments

The GCOS is a validated, 24-item instrument that measures empowerment (defined as: “…a set of beliefs that enable a person from a family affected by a genetic condition to feel that they have some control over and hope for the future.” (17)). Each item is rated on a 7-point anchored Likert scale (1= strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Scores range from 24 to 168 with higher scores indicating higher levels of empowerment. In accordance with instructions regarding use of the instrument, data were imputed for participants who were missing items and participants who left more than five items blank were excluded from analysis. All clients (regardless of whether they had a personal or family history of psychiatric illness, or both) attending the psychiatric GC clinic completed the GCOS whenever possible.

The IMSES is a 9-item, self-report questionnaire that measures self-efficacy related to illness management (that is, confidence to manage one’s own illness). Each item is rated on a 10-point anchored Likert scale (1 = not at all confident and 10 = completely confident). Mean item scores were used, where higher scores indicate higher levels of self-efficacy. Only clients who had a personal history of psychiatric illness completed the IMSES.

Analyses

We applied descriptive statistics to the demographic data, and assessed the GCOS and IMSES data for normality of distribution. While the GCOS data were normally distributed, those from the IMSES were skewed. We applied a natural log transformation, followed sequentially by a square root transformation and square transformation, the last of which produced a normal distribution. We then used paired sample t-tests to analyze the difference in GCOS and IMSES scores from pre (T1) to post (T2) GC. Specifically, we looked at the difference in score from T1 to T2 by conducting four tests: 1) difference IMSES scores among participants with personal history of mental illness (this scale was only completed by those with mental illness), 2) difference in GCOS scores among all participants, 3) difference in GCOS scores among participants with personal history of mental illness, and 4) difference in GCOS scores among participants with no personal history of mental illness. A significance threshold (α) of p<0.0125 was applied (to allow for the four tests we performed at a nominal overall significance level of 0.05).

RESULTS

A total of 143 clients accessed the psychiatric GC service during the first year of operation (in the context of 110 unique appointments). Seven clients were ineligible to participate (e.g. unable to consent), and of the remaining 136, 75 (55.1%) consented to allow their data to be used for research purposes (from a total of 68 unique appointments).

Demographics

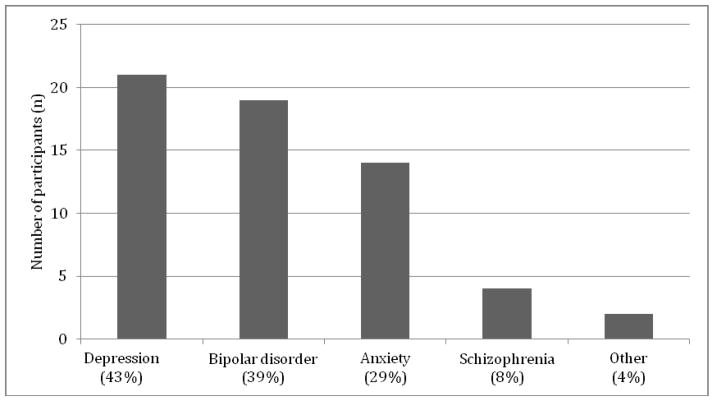

Participants’ ages ranged from 24 – 82 with a mean age of 45.9 years old, the majority were European (76.7%, n = 56, data missing for two participants), had self-referred (76%, n=57), and reported a personal diagnosis of a mental illness (65.3%, n=49 – see Figure 1). Of the 18 patients who were referred by a healthcare provider (24% of total), 52.6% (n = 10) were referred by psychiatrists.

Figure 1. Mental illness diagnoses amongst those with a personal history of mental illness who attended the psychiatric genetic counseling clinic.

49 participants had a personal history of mental illness. Of these, 39 reported a single diagnosis, and 10 reported more than one diagnosis. Of the latter, 9 reported two diagnoses and 1 reported four diagnoses.

Characteristics of the subset consenting to participate are highly representative of all index clients who have been seen in the clinic over the same time frame (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics between all clinic attendees and those who consented to participate.

| All index clients seen at the clinic (%) | Study participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 85.6 | 85.3 |

| Male | 14.4 | 14.7 |

|

| ||

| Mental illness history | ||

| Family history only | 33.7 | 34.7 |

| Personal history | 66.3 | 65.3 |

|

| ||

| Appointment method | ||

| In person | 80 | 80 |

| Telephone | 13.6 | 12 |

| Telehealth | 6.3 | 8 |

|

| ||

| Number of attendees | ||

| Single individual | 74.5 | 70.7 |

| Multiple family members | 25.3 | 29.3 |

Main Reason For Appointment

Often participants provided more than one reason for attending the genetic counseling session (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants’ main reason for coming to appointment

| % (n) | % (n) participants with mental illness | % (n) participants without a mental illness | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| To understand causes of mental illness | 58.7 (44) | 38.7 (29) | 20 (15) |

|

| |||

| To learn ways to protect mental health | 21.3 (16) | 13.3 (10) | 8 (6) |

|

| |||

| To learn chance of illness recurrence | |||

| overall | 64 (48) | 45.3 (34) | 18.7 (14) |

| for selfa | 5.3 (4) | 1.3 (1) | 4 (3) |

| for childa | 52 (39) | 36 (27) | 16 (12) |

| for other relative (grandchildren, nieces, nephews) | 10.7 (8) | 9.3 (7) | 1.3 (1) |

3 participants asked to learn chances of illness recurrence for both themselves and their child

Empowerment (GCOS)

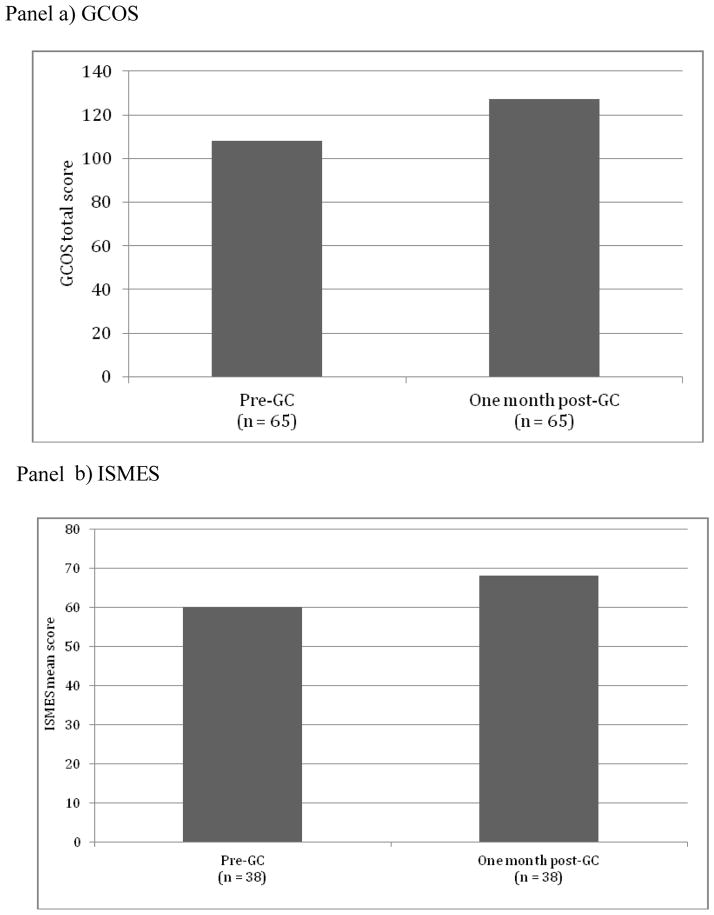

Internal consistency of the GCOS in this population was good (Cronbach’s α=0.86). In the complete sample (participants with and without personal history of mental illness combined), there was a significant increase in empowerment as measured by the GCOS at T2 (M = 127.00) in comparison to T1 (M= 108.46). [T (64) = −7.89, p < 0.0001 (effect size, d=1)]. See Figure 2, panel a. The same pattern of significance was reflected in both subgroups of individuals who reported a diagnosis of mental illness (n = 45, T1: M = 109.29 and T2: M = 128.5284, T (44) = −6.419, p<0.0001), and those with no personal history of mental illness (n = 20, T1: M = 106.6000, to T2: M = 123.5615, T (19) = −4.597, p<0.0001).

Figure 2. GCOS and IMSES Scores before (T1) and after (T2) GC.

The IMSES was completed by those with personal history of mental illness only. The GCOS data shown are those from the whole sample combined. When it was not possible to gather family history data in advance of the GC appointment, GCOS/ISMES was not completed at T1, due to time limitations. Not all participants could be reached for T2, or declined to complete the questionnaire at this time-point. For the IMSES, some participants did not identify as having a personal history of psychiatric illness at T1 until rapport had been established during the GC appointment (which precluded the completion of the questionnaire at T1), or would identify as having e.g. depression or anxiety but would decline to complete the ISMES as they did not feel it related to them at their present point of recovery. IMSES mean scores are square transformed.

Self-efficacy (ISMES)

Internal consistency of the ISMES in this population was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). There was a significant increase in self-efficacy as measured by the ISMES at T2 (M=68.1) as compared to T1 (M=60.2) [T(37) = −2.67 p = 0.011 (effect size, d=0.43)]. See Figure 2, panel b.

DISCUSSION

This study constitutes what is - to our knowledge - the first examination of the effects of GC for people with psychiatric disorders and their family members in a naturalistic setting, and the first time that either self-efficacy or empowerment has been studied as an outcome of GC for psychiatric disorders. Receiving GC (according to the model described above) was associated with increased levels of empowerment among clients with and without a personal history of mental illness one month later. Similarly, among clients who had a personal history of mental illness, increased levels of self-efficacy were observed one month after GC. It is of note that not only were the changes in the outcome measures statistically significant, but also the effect sizes that were observed were of a magnitude (large for empowerment, and moderate for self-efficacy) that are typically considered to be reflective of clinically meaningful differences (26). This work adds to the accumulating data regarding positive outcomes of GC for people with psychiatric disorders and their family members (12–14), and suggests that there may be value in making this kind of intervention more widely available to this population –especially given the interest in the intervention amongst members of this group. Indeed, in previous studies, >90% of people with mental illness and their relatives would like GC, but only very small numbers have received it (10, 11, 16, 27).

Although we are aware of no previous studies exploring the effect of psychiatric GC on empowerment or self-efficacy, our findings of increases in these measures after GC is not entirely unexpected. First, these constructs are often conceptualized as being the counterpoint to or opposite of internalized stigma (28–30), and previous studies have linked psychiatric GC with decreases in internalized stigma (12–14). Second, empowerment has been identified by clients attending GC appointments for non-psychiatric reasons as one of the most important outcomes of GC (31). Increases in empowerment and self-efficacy are important psychosocial outcomes because of they relate to decreases in hopelessness, helplessness and secrecy, improvements in quality of life, ability to cope, availability of emotional support (32), and increased likelihood of help seeking for psychiatric problems (33).

It seems important to note that while in the broader medical community, the term “genetic counseling” is frequently used to refer (often implicitly) to an (often brief) information provision-based interaction involving communication about risks for other family members to be affected and/or discussion of genetic testing. However, the outcomes we describe here were associated with the provision of an intervention that incorporated this kind of information into a highly psychotherapeutically-oriented interaction (as described), and thus, these would not necessarily be expected from a brief, information-provision based interaction. Also, it is important to explicitly acknowledge that the changes in empowerment and self-efficacy we observed were not influenced by the provision of genetic test results (no genetic testing was ordered, as described above).

Genetic counselors have a unique skill set that positions them to provide GC for people with psychiatric disorders and their families with the kind of effect described here. However, research shows that some genetic counselors feel uncomfortable asking about psychiatric disorders, and feel that discussing what is known about the etiology of these conditions and/or discussing risk relating to these conditions is more confusing or worrisome than it is helpful (15). The data presented here supports other work (34) refuting the notion that providing GC services relating to psychiatric disorders are not helpful.

Recent research showed that the public typically associates GC with risk communication (35), and in this study, the most frequently cited reason for attending GC was to understand the chances for other family members to develop mental illness. However, more than half of participants attended because they wanted to better understand the causes of mental illness, and almost a quarter because they wanted to know what they could do to protect their mental health. This highlights the idea that GC can be of benefit to individuals with mental illness and their families, regardless of whether family planning is a currently relevant issue.

In establishing the clinic, we recognized the need to reduce barriers to access as far as possible, given the disadvantaged and underserved nature of the population. Healthcare services in BC are already covered financially for residents, but in recognition of the fact that some people (and perhaps particularly those with psychiatric disorders) may not have a healthcare provider from whom they would feel comfortable seeking a referral, we opted for a clinical model that accommodates self-referrals. The sizable proportion of individuals who self-referred to the clinic suggests that this strategy may be important.

The IMSES and GCOS were useful as clinical assessment tools (both when contracting, and in post counseling discussions about the impact of the session), were well accepted by clients, and allowed for evaluation of outcomes of GC. Given the increasing recognition within the genetic counseling profession of the importance of measuring outcomes, it seems important to highlight the fact that this model could readily be adapted and applied to other clinical contexts.

Last, it is important to comment on the fact that though it is typical in medical genetics contexts to seek records to confirm diagnoses related to the referral, this is not the practice of the specialist clinic on which we report here. This could be considered to be a limitation, and thus requires explication. The purpose of obtaining medical records in other medical genetics settings is related to ensuring establishment of a correct genetic diagnosis underlying symptomatology and to ensure provision of accurate probabilities for recurrence of condition in other family members. However, the goal of the clinic described here is not to provide diagnoses of underlying genetic syndromes, but rather to help individuals understand the broad concepts underlying psychiatric illness etiology (which are similar irrespective of the specific diagnosis), and provide psychotherapeutically-oriented support to manage the attendant emotional challenges of this information. Further, the challenges with the issue of obtaining medical records to confirm diagnosis that may occur in the context of any referral indication (e.g. family estrangement, consent to access family member records) can be accentuated in this population, by nature of the indication. In addition, there are challenges that are more particular to this population (e.g. inherent subjectivity of, and changes in diagnoses over time). Combined, these issues result in obtaining medical records in this context being time consuming, labor intensive, and – arguably - of less value here as compared to other medical genetics contexts, given the purpose of the intervention. However, having confidence in the reported diagnoses remains important, especially with regard to establishing accurate estimates of probabilities for recurrence, and it is for this reason that we adopted the approach outlined here, of ensuring the genetic counselor is trained/experienced in psychiatric interviewing (specifically, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (36), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (37), and Family Interview for Genetic Studies (a research tool which can be used to determine a psychiatric diagnosis in a third party based on information gathered from interviewing a relative) (38). While it is clearly not within a genetic counselor’s scope of practice to make psychiatric diagnoses, it is well within their scope of practice to ascertain and document detailed medical and family histories, and our view is that psychiatric interviewing constitutes the skill relevant to effectively ascertaining and documenting a detailed family history in this specialist context. Information obtained from patients using these skills can be brought forward for consultation with the clinic’s psychiatrist as needed (e.g. in the case of discrepancy between diagnoses reported by the patient and suspected by the counselor).

Limitations

This was a naturalistic study of the outcomes of genetic counseling in a real-world clinical context, and as such there was no control group. Thus, we cannot unequivocally attribute the changes in self-efficacy and empowerment that were observed to the intervention. Further, while changes in self-efficacy and empowerment were observed over a one-month time-frame, it is not clear whether these changes persisted over longer periods. The majority of participants in the study were female –thus it is not clear how representative these data are of men’s experiences. All of these questions could be fruitful avenues for future research. Last, the rate with which people consented to allow their data to be used for research was relatively low. This could be related to the fact that many clients had not read the consent form that was sent prior to the appointment (which necessitated provision of a stamped addressed envelope and instruction to return the completed consent form if they decided to participate), but could also potentially be related to stigma – this represents and interesting avenue for future investigations.

Conclusion

In this – the first study of which we are aware to explore the effect of psychiatric genetic counseling in a naturalistic setting – we found increases in empowerment and, among those with a personal history of mental illness, self-efficacy. The magnitude of the difference in these measures was in the range of those that are typically considered to be reflective of clinically meaningful differences. In this study “genetic counseling” was operationalized not as an information provision-based interaction involving communication about risks for other family members to be affected and/or discussion of genetic testing, but rather as a brief but psychotherapeutically-oriented interaction focused specifically on the implications of understanding the etiology of the condition (as per published, practice-based competencies for genetic counselors (39)). While there is much scope for future research, these data add to the growing body of literature documenting the positive effects of genetic counseling for people with mental illness and their families, and suggest value in making the services that can be provided by specialty-trained genetic counselors more widely available to this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. W Honer for his invaluable support in establishing the clinic, and Lori Hamanishi for her administrative support. The authors also thank Kim Jensen and Suvina To for their assistance with administrative tasks.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, BC Mental Health and Addictions Services, and BC Children and Women’s Hospital. JA was supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program, and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

AI provides genetic counseling in the context of the clinic described. All other authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that might bias the work.

References

- 1.Williams L, Jacka F, Pasco J, Henry M, Dodd S, Nicholson G, et al. The prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in australian women. Australas Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;18(3):250–5. doi: 10.3109/10398561003731155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text revision. 4. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skirton H, Eiser C. Discovering and addressing the client’s lay construct of genetic disease: An important aspect of genetic healthcare? Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003 Winter;17(4):339–52. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.17.4.339.53195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin JC, Honer WG. The genomic era and serious mental illness: A potential application for psychiatric genetic counseling. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Feb;58(2):254–61. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S. Illnress representations: Theoretical foundations, in Perceptions of health and illness: Current research and applications. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman J, editors. Perception of Health & Illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers and Overseas Publishers Association; 1997. pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamm JL, Nussbaum RL, Biesecker BB. Genetics and alcoholism among at-risk relatives I: Perceptions of cause, risk, and control. Am J Med Genet A. 2004 Jul 15;128A(2):144–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor SE. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist. 1983;38(11):1161–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau R, Hartman KA. Common sense representations of common illnesses. Health Psychology. 1983;2:167–85. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resta R, Biesecker BB, Bennett RL, Blum S, Hahn SE, et al. National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Definition Task Force. A new definition of genetic counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ task force report. J Genet Couns. 2006 Apr;15(2):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyus VL. The importance of genetic counseling for individuals with schizophrenia and their relatives: Potential clients’ opinions and experiences. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007 Dec 5;144B(8):1014–21. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLisi LE, Bertisch H. A preliminary comparison of the hopes of researchers, clinicians, and families for the future ethical use of genetic findings on schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006 Jan 5;141B(1):110–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin JC, Honer WG. Psychiatric genetic counselling for parents of individuals affected with psychotic disorders: A pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008 May;2(2):80–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costain G, Esplen MJ, Toner B, Hodgkinson KA, Bassett AS. Evaluating genetic counseling for family members of individuals with schizophrenia in the molecular age. Schizophr Bull. 2012 Oct 27; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costain G, Esplen MJ, Toner B, Scherer SW, Meschino WS, Hodgkinson KA, et al. Evaluating genetic counseling for individuals with schizophrenia in the molecular age. Schizophr Bull. 2012 Dec 12; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monaco LC, Conway L, Valverde K, Austin JC. Exploring genetic counselors’ perceptions of and attitudes towards schizophrenia. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13(1):21–6. doi: 10.1159/000210096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter MJ, Hippman C, Honer WG, Austin JC. Genetic counseling for schizophrenia: A review of referrals to a provincial medical genetics program from 1968 to 2007. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Jan;152A(1):147–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAllister M, Wood AM, Dunn G, Shiloh S, Todd C. The genetic counseling outcome scale: A new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services. Clin Genet. 2011 May;79(5):413–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludman EJ, Simon GE, Rutter CM, Bauer MS, Unutzer J. A measure for assessing patient perception of provider support for self-management of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002 Aug;4(4):249–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biesecker BB. Genetic counseling for mental illness: Goals resemble counseling goals for other common conditions. Clin Genet. 2006 Jan;69(1):93, 4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00554a.x. author reply 94–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peay HL, Austin JC. How to talk with families about genetics and psychiatric illness. 1. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowlin-Finch NL, Altshuler LL, Szuba MP, Mintz J. Rapid resolution of first episodes of mania: Sleep related? J Clin Psychiatry. 1994 Jan;55(1):26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peet M, Horrobin DF. A dose-ranging study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with ongoing depression despite apparently adequate treatment with standard drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;59(10):913–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheewe TW, Backx FJ, Takken T, Jorg F, van Strater AC, Kroes AG, et al. Exercise therapy improves mental and physical health in schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013 Jun;127(6):464–73. doi: 10.1111/acps.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veach PM, Bartels DM, Leroy BS. Coming full circle: A reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice. J Genet Couns. 2007 Dec;16(6):713–28. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costain G, Lionel AC, Merico D, Forsythe P, Russell K, Lowther C, et al. Pathogenic rare copy number variants in community-based schizophrenia suggest a potential role for clinical microarrays. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Nov 15;22(22):4485–501. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sloan J, Symonds T, Vargas-Chanes D, Fridley B. Practical guidelines for assessing the clinical significance of health-related quality of life changes within clinical trials. Drug Information Journal. 2003;37:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quaid K, Aschen S, Smiley C, Nurnberger J. Perceived genetic risks for bipolar disorder in a patient population: An exploratory study. Journal of genetic counseling. 2001;10(1):41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corrigan PW. Empowerment and serious mental illness: Treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatr Q. 2002 Fall;73(3):217–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1016040805432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010 Dec;71(12):2150–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shih M. Positive stigma: Examining resilience and empowerment in overcoming stigma. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:175–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAllister M, Payne K, Macleod R, Nicholls S, Dian D, Davies L. Patient empowerment in clinical genetics services. J Health Psychol. 2008 Oct;13(7):895–90. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angermeyer MC, Schulze B, Dietrich S. Courtesy stigma--a focus group study of relatives of schizophrenia patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003 Oct;38(10):593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0680-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009 Oct;66(5):522–41. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hippman C, Lohn Z, Ringrose A, Inglis A, Cheek J, Austin JC. “Nothing is absolute in life”: Understanding uncertainty in the context of psychiatric genetic counseling from the perspective of those with serious mental illness. J Genet Couns. 2013 Oct;22(5):625–32. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9594-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maio M, Carrion P, Yaremco E, Austin JC. Awareness of genetic counseling and perceptions of its purpose: A survey of the canadian public. J Genet Couns. 2013 Dec;22(6):762–70. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9633-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maxwell ME. Manual for the FIGS (Family Interview for Genetics Studies) Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Mental Health, Clinical Neurogenetics Branch, Intramural Research Program; Mar 30, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling. [Accessed 23rd Dec 2013];Practice based competencies for genetic counselors. 2013 http://gceducation.org/Documents/ACGC%20Practice%20Based%20Competencies_13-Final-Web.pdf.