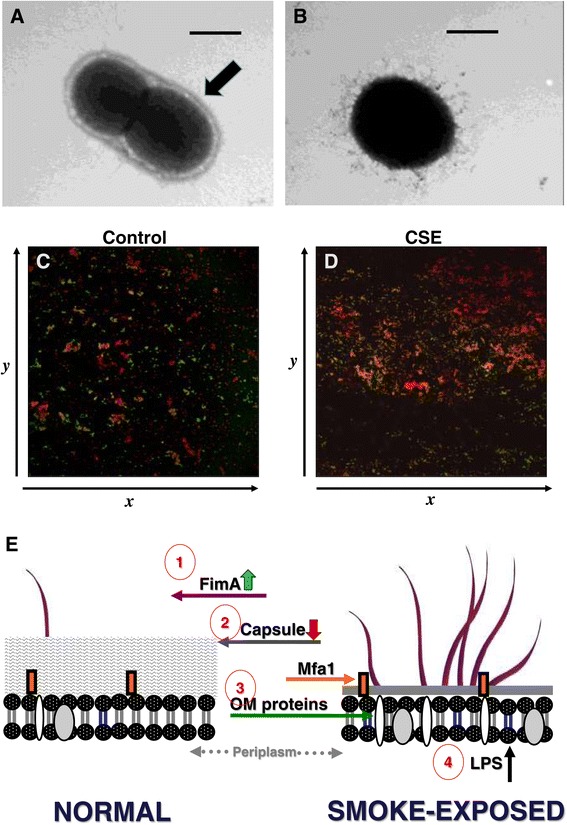

Figure 2.

Cigarette smoke extract alters key P. gingivalis surface molecules and enhances biofilm formation. Representative transmission electron microscope images of P. gingivalis grown in control medium (A) or CSE-conditioned medium (B) are shown. The black arrow indicates the P. gingivalis capsule, which is greatly reduced in the presence of CSE. Images and data taken from Bagaitkar et al. [6]. (C, D) S. gordonii cells (hexidium iodide-labeled, red) were placed on a saliva-coated coverglass in a flow cell. P. gingivalis cells (FITC conjugated anti-P. gingivalis IgG-labeled, green) were passed through. P. gingivalis-S. gordonii microcolonies (yellow) were visualized by confocal microscopy. The number of dual species microcolonies formed was significantly greater in the CSE-exposed cells compared to the controls (p < 0.01). Observation first published in [31] but data previously unpublished in this form. (E) A model of cigarette smoke extract-induced alterations to the surface of the periodontal pathogen, P. gingivalis, is presented. (1) Surface expression of the major fimbrial protein (FimA), but not the minor fimbrial antigen (Mfa1), is upregulated [6]. (2) At the same time, the highly pro-inflammatory capsule is inhibited by CSE, increasing fimbrial protein bioavailability. (3) Multiple outer membrane proteins are upregulated upon cigarette smoke exposure, including the highly antigenic RagB protein [6]. The biological significance of CSE-induced alterations to the membrane proteome is currently under investigation. (4) While we have not examined P. gingivalis directly, the LPS profile in the saliva of smokers, compared to that of non-smokers, exhibits altered 3-OH fatty acid content derived from overall oral microbiome [55].