Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: DC-SIGN, lentiviral vector, immunotherapy

Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are essential antigen-presenting cells for the initiation of cytotoxic T-cell responses and therefore attractive targets for cancer immunotherapy. We have developed an integration-deficient lentiviral vector termed ID-VP02 that is designed to deliver antigen-encoding nucleic acids selectively to human DCs in vivo. ID-VP02 utilizes a genetically and glycobiologically engineered Sindbis virus glycoprotein to target human DCs through the C-type lectin DC-SIGN (CD209) and also binds to the homologue murine receptor SIGNR1. Specificity of ID-VP02 for antigen-presenting cells in the mouse was confirmed through biodistribution studies showing that following subcutaneous administration, transgene expression was only detectable at the injection site and the draining lymph node. A single immunization with ID-VP02 induced a high level of antigen-specific, polyfunctional effector and memory CD8 T-cell responses that fully protected against vaccinia virus challenge. Upon homologous readministration, ID-VP02 induced a level of high-quality secondary effector and memory cells characterized by stable polyfunctionality and expression of IL-7Rα. Importantly, a single injection of ID-VP02 also induced robust cytotoxic responses against an endogenous rejection antigen of CT26 colon carcinoma cells and conferred both prophylactic and therapeutic antitumor efficacy. ID-VP02 is the first lentiviral vector which combines integration deficiency with DC targeting and is currently being investigated in a phase I trial in cancer patients.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are pivotal for the initiation of all antigen-specific immune responses and are being explored as attractive targets for cancer immunotherapy.1,2 To generate robust CD8 T-cell responses, the efficient presentation of antigen via MHC class I as well as maturation of the DC are required. Recombinant vectors are effective in priming CD8 T cells because they can deliver antigen for MHC class I presentation to target cells via de novo transcription and translation, as well as the required costimulatory signals to antigen-presenting cells via toll-like receptor stimulation.3 An ideal vector system for antigen-directed immunotherapy would therefore have the ability to specifically target DCs in vivo to maximize antigen presentation and avoid potential off-target toxicity. To this end, integration-competent lentiviral vectors (LVs) have been engineered that target DC and induce immune responses,4,5 however, none has been evaluated clinically in the setting of immunotherapy to date.

We have advanced a prototype vector to generate the ID-VP02 immunotherapy platform suitable for selective in vivo targeting of human DCs by virtue of pseudotyping with a modified envelope protein of the DC-tropic Sindbis virus which targets the DC-SIGN receptor expressed on immature DC.4,6

ID-VP02 is unique among other third-generation LVs and compared with the prototype it was derived from in a number of ways. ID-VP02 was rendered integration deficient by several redundant mechanisms including mutations in the vector backbone as well as the integrase catalytic domain. This is an important safety feature when systemic administration of the vector is considered. The ∆U3 of the vector transfer genome contains an extended deletion in the 3′ end compared with the usual self-inactivating (SIN) deletion, which decreases the risk of recombination and has been reported to increase antigen expression.7,8 To overcome SAMHD1-mediated restriction of the vector in human DCs and improve expression of the transgene, the Vpx protein from SIVmac was packaged in the vector.9,10 Finally, the vector is manufactured in the presence of the mannosidase type I inhibitor kifunensine, which results in enhanced affinity of the Sindbis envelope to DC-SIGN.6 Taken together, the vector possess a novel combination of safety and efficacy enhancing features designed to increase the likelihood of it achieving the desired biological activity in humans, while minimizing the risk of off-target effects.

We report here the preclinical assessment of the ID-VP02 platform, with characterization of the cell tropism, tissue biodistribution, immunological activity, and antitumor efficacy in the mouse. We find that ID-VP02 is able to utilize mSIGNR1, a human DC-SIGN homolog expressed on mouse DCs, as a functional receptor, supporting the utility of the mouse as a preclinical model. We demonstrate furthermore the ability of ID-VP02 to generate robust, boostable CD8 T-cell responses from naive precursors that provide protection against both viral and tumor challenge, including in the therapeutic setting. Collectively, these results provide in vivo proof-of-concept of our novel lentiviral vector platform and support the development of ID-VP02-based clinical candidates in oncology settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ID-VP02 Construction

The design and production of ID-VP02 was described previously.6,11). Briefly, ID-VP02 is produced through transient transfection of 293T cells with 5 plasmids: the transfer vector (ID-VP02 genome), a modified gagpol transcript (RI-gagpol), accessory protein Rev from HIV-1, accessory protein Vpx from SIVmac, and the E1001 envelope glycoprotein variant of Sindbis virus. The Sindbis envelope of the VP02 vector described here is significantly different from the envelope used by Yang et al4 because (i) the furin cleavage of the envelope protein was restored; (ii) the envelope contains several point mutations which increase affinity to DC-SIGN; and (iii) the vector is manufactured in the presence of the mannosidase type-1 inhibitor kifunensine, which results in N-terminal high-mannose glycosylation of the envelope protein.6 Together, these modification enhance selectivity of VP02 for DC and improve transduction efficacy of human DC in vitro.

Like other third-generation LVs, ID-VP02 is devoid of all accessory proteins, except for Rev, and is encoded by a split genome with a self-inactivating deletion in the U3 region (ΔU3) of the 3′LTR. ΔU3 prevents transcription of the full-length vector genome from reverse-transcribed dsDNA vectors in the infected target cell7 and also minimizes the risk of insertional transcriptional activation mediated by the 3′LTR. ID-VP02 has a split genome and contains a self-inactivating (SIN) deletion in the 3′LTR (ΔU3), similar to other third-generation LVs. The U3 deletion has been extended to cover the 3′-poly purine tract (3′PPT)4 and favors the formation of single-LTR episomal circles upon reverse transcription that are not capable of chromosomal integration.12 In addition, a D64V catalytic mutation in the integrase enzyme, encoded by the pol gene, reduces the integration competence of the vector.13 A codon optimized gagpol plasmid allows for production that is devoid of the HIV-Rev response element (RRE), minimizing the chance of psi-gag recombination and thereby reducing the likelihood for formation of Replication Competent Lentivirus during vector production.11,14,15 Vpx from SIVmac is included as an accessory protein to overcome SAMHD1-mediated restriction in human DCs by promoting its degradation.8,9 The genome contains an antigen cassette downstream of the human Ubiquitin-C promoter that has been modified to have its natural intron deleted (ΔUbiC).

Vector Quantitation

Genomic RNA was isolated from vector particles using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). To eliminate contaminating DNA, the extracted nucleic acid was then digested with DNase I (Invitrogen). Two dilutions of each DNase I-treated RNA sample were then analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using the RNA Ultrasense One-Step Quantitative RT-PCR System (Invitrogen) and previously described vector-specific primers and probe.16 The vector RNA copy number was calculated in reference to a standard curve comprised of linearized plasmid DNA containing the target sequences, diluted over a 7-log range (1×101 to 1×107 copies). As each vector particle is predicted to contain 2 single-stranded copies of genomic RNA, the vector RNA copy number was divided by 2 to give the genomic titer used throughout the experiments. For some experiments, vector was quantified by quantification of p24, using the HIV-1 p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit by Advanced Bioscience Laboratories (Rockville, MD), following the manufacturer’s directions.

Recombinant Cell Lines

DC-SIGN or its murine homologs SIGNR1, SIGNR3, and SIGNR5 were cloned individually into a retroviral (Clontech) or lentiviral expression system containing puromycin resistance. Vectors were prepared in small scale as described6 and used to transduce HT1080 cells (ATCC, CCL-121) at high multiplicity of infection. Twenty-four hours after transduction, media was replaced with puromycin containing media.

Green Fluorescent Protein Transduction Assay

HT1080 cells stably expressing DC-SIGN were plated at 4×104 cells/well in a 12-well plate in 1 mL DMEM media containing 5% serum, l-glutamine, and antibiotics. Twenty-four hours later, cells in each well were transduced with 2-fold dilutions of vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP). For the detection of ID-VP02, neutralizing antibodies vectors were preincubated for 1 hour with the indicated dilution of serum. Each amount of vector is prepared in a 1 mL final volume in complete DMEM. As a control for pseudotransduction, 10 µM of the reverse-transcriptase inhibitor nevirapine was used with the highest volume of vector in a parallel well. Forty-eight hours after transduction cells were analyzed for GFP expression by Guava (Millipore), Green Fluorescence Units (GFU) per milliliter was calculated by using a best fit (least squares) linear regression model based on the volumes of vector and the resulting percent GFP values using the FORECAST function in Excel (Microsoft). Events that resulted in <1% of GFP+ cells were set as the limit of quantification.

Animals

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in a BSL-2 level room in the Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI) animal facility. All procedures were approved by the IDRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunizations

Aliquots of ID-VP02 stored at −80°C were thawed at room temperature and then kept on ice. Vector was serially diluted in cold sterile HBSS and transported to the animal facility for injection. Mice were placed in a conventional slotted restrainer with the tail base accessible. Vector was administered via 50-μL injection using a 29-G 0.3-mL insulin syringe [Becton Dickenson (BD)] inserted subcutaneously on the right side of the tail base, approximately 1 cm caudal to the anus, leading to minor but notable distension of the skin around the tail base.

SIGNR1 and 5 Expression In Vivo

Cells from individual spleens or pools of 10 popliteal lymph nodes from 5 mice were stained in FACS buffer (PBS, 1% FCS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.01% sodium azide) in the presence of FcR blocking antibody 2.4G2 and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (L/D NIR; Invitrogen). Antibodies used for surface staining included anti-mouse CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (eBioscience) or CD4-Alexa Fluor 700 (eBioscience), CD8-Pacific Blue (eBioscience), and B220-V500 (BD). After surface staining, cells were fixed with Cytofix (BD) and analyzed on a LSRFortessa multiparametric flow cytometer. Live, single-cell events (L/D NIR−, SSH=SSA) were subdivided into B cells (B220+ TCRβ−), T cells (TCRβ+, B220−), and DCs (B220− TCRβ− MHC II+ CD11chi). Gates for SIGNR5 and SIGNR1 expression each of these subsets was set using negative control stains lacking SIGNR1-specific and SIGNR5-specific antibodies, such that frequencies of positive events were ≤0.00.

ID-VP02-GFP Transduction In Vivo

BALB/c mice (n=15/group) were injected subcutaneously in the footpad with 3×1010 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, control ID-VP02 encoding the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1, or left untreated. Four days later, the draining popliteal or nondraining cervical lymph nodes were pooled from 5 mice (3 pools per treatment group) and live (L/D singlet events (L/D NIR−, SSH=SSA) were analyzed for the presence of GFP. The phenotype of GFP+ cells was determined by costaining with anti-mouse CD11c-PE-Cy7 (eBioscience), MHC II-Pacific Blue (eBioscience), SIGNR5-PE (eBioscience), and SIGNR1-APC (eBioscience).

Vector Biodistribution

C57BL/6 mice (n=3/group) received 3×1010 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding the polyepitope construct LV1b (described later) or buffer HBSS subcutaneously at the base of the tail. The presence of reverse-transcribed vector DNA was analyzed by qPCR at 1, 4, 8, 21, or 42 days postinjection in the following tissues: site of injection (tail base), spleen, liver, heart, ovaries, brain, and draining (inguinal) and nondraining (cervical) lymph node. Tissues were processed in Fastprep Lysing Matrix D tubes using a Fastprep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) and genomic DNA was isolated from homogenates using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc.). Eluted DNA (200 ng per sample) was analyzed by qPCR in quadruplicate using EXPRESS qPCR Supermix Universal (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and a primer/probe set designed to amplify a target sequence of 85 bp within the LV1b cassette. All reactions were performed using the Bio-Rad CFX384 and analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The vector DNA copy number was calculated in reference to a standard curve comprised of plasmid DNA containing the target sequences diluted over a 7-log range (101–107 copies).

Vector Off-Target Transduction Analysis

A panel of human primary cells, some of which are known to express the DC-SIGN homologue L-SIGN (liver/lymph node–specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing integrin) were purchased from Innoprot (Spain) and Cell Biologics (Chicao, IL). Serial dilutions of ID-VP02 (1.5×106–1.5×109 vector genomes) were incubated with target cells in 96-well microtiter plates. The cell line 293T huDC-SIGN, previously shown to be permissive for ID-VP02 transduction, was used as an assay positive control cell type. The transduction step was performed both in the presence and absence of the reverse-transcriptase inhibitor nevirapine as a means to measure and later subtract nonspecific (ie, nontransduction) background signal. In each case, the number of target cells was kept constant (8×104 cells), such that the range of input vector tested for each cell type was 2×101 to 2×104 vector genomes/target cell, representing a range of multiplicities of infection. At 1 day posttransduction, cells were lysed in situ by the addition of a buffer containing sodium deoxycholate, Tween-20, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and proteinase K. The cell lysates were then incubated sequentially at 37°C, 55°C, and 95°C to ensure proteolysis and DNA denaturation. Denatured cell lysates were analyzed in quadruplicate by qPCR (ABI 7900HT; Life Technologies) using EXPRESS qPCR Supermix Universal (Life Technologies) and a vector-specific primer/probe set. For each cell type tested, transduction events were averaged from each of the 4 input vector dilutions (after accounting for dilution factor) and the overall rate of transduction was expressed as a percentage relative to the control cell 293T huDC-SIGN. Viability of the cell types did not appear to be adversely affected by the addition of ID-VP02 (with or without nevirapine) as determined by measurement of metabolic activity (MTS reduction assay; Promega Corp., Madison, WI) on a parallel set of samples of each cell type.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS)

Spleens were homogenized by pressing through a 70 μM nylon filter. Red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic shock by brief exposure to ice-cold ultrafiltered water followed by immediate isotonic restoration with 10× PBS. For analysis of cytokines, cells were stimulated in 96-well plates with peptides at a concentration of 1 μg/mL per peptide in complete RPMI (10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and l-glutamine) for 5 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Peptides, including OVA257 (SIINFEKL), LCMV GP33 (KAVYNFATM), AH1 (SPSYVYHQF), and AH1A5 (SPSYAYHQF) were manufactured at 95% purity by AnaSpec (Fremont, CA). In some experiments, as noted, anti-mouse CD107a-PerCP-eF710 (eBioscience) was included in the stimulation cocktail to capture translocated CD107a on the surface of degranulating T cells. After stimulation, surface staining was carried out in FACS buffer (PBS, 1% FCS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.01% sodium azide) in the presence of FcR blocking antibody 2.4G2 and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (L/D NIR; Invitrogen). Antibodies used for surface staining in in-vivo experiments included anti-mouse CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5 (eBioscience) or CD4-Alexa Fluor 700 (eBioscience), CD8-Pacific Blue (eBioscience), and B220-V500 (BD). After surface staining, cells were fixed with Cytofix (BD) and stored at 4°C overnight in FACS buffer. Cells were then permeabilized with Perm/Wash buffer (BD) containing 5% rat serum (Sigma Aldrich). Antibodies for intracellular staining were diluted in Perm/Wash buffer containing 5% rat serum and added to permeabilized cells. Antibodies included anti-mouse TNFα-FITC (eBioscience), IFNγ-PE (eBioscience), and IL-2-APC (eBioscience). Cells were washed twice with Perm/Wash buffer and resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed on a 3-laser LSRFortessa with High Throughput Sampler (BD). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Viable CD8 T cells were gated as follows: lymphocytes (FSCint, SSClo), single cells (SSC-A=SSC-H), live (L/D NIRlo), B220− CD4− CD8+. Cytokine gates were based on the 99.9th percentile (0.1% of positive events in unstimulated cells) and the CD107a gate was based on the 99th percentile.

MHC I Multimer and Memory Phenotype Analysis

Splenocytes prepared as described previously were stained with H-2Kb-OVA257 MHC I pentamers (ProImmune, Oxford, UK) in room temperature FACS buffer for 10 minutes in the presence of 2-4G2 antibody. Cells were washed once and stained with surface antibodies plus L/D NIR for 20 minutes on ice. Antibodies included CD127-FITC, CD44-PerCP-Cy5.5, KLRG1-APC, CD8-Alexa Fluor 700 (all from eBioscience), and B220-V500 (BD). Cells were washed, fixed with Cytofix, and analyzed as previously. Within the viable CD8 T-cell population, CD44hi H-2Kb-OVA257 pentamer+ events, gated based on the 99.9th percentile in unimmunized mice, were analyzed for their expression of KLRG1 and CD127.

Vaccinia Virus Challenge

C57BL/6 mice were immunized subcutaneously in the tail base on day 0 with a dose range of ID-VP02 encoding the LV1b polyepitope or with HBSS vehicle. The LV1b model antigen construct contains the following epitopes with known class I and class II binding: OVA257 (SIINFEKL, H-2Kb), LCMV GP33 (KAVYNFATM, H-2Db), human gp10025 (KVPRNQDWL, H-2Db), mouse CT26 AH1A5 (SPSYAYHQF, H-2Ld), OVA323 (ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR, I-Ad and I-Ab), and LCMV GP61 (GLKGPDIYKGVYQFKSVEFD, I-Ab); only the responses to OVA257 and GP33 were monitored for these studies. Five weeks after immunization, mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 1×107 TCID50 recombinant vaccinia virus expressing OVA (rVV-OVA), 1×107 TCID50 wild-type vaccinia virus (VV-WT), or HBSS vehicle. Five days after challenge, spleens were harvested for OVA257-specific and LCMV GP33-specific ICS as described previously, and ovaries were harvested for quantitation of viral load by TCID50 assay.

In Vivo Cytotoxicity Assay

BALB/c mice (3 per group) were immunized subcutaneously at the tail base with ID-VP02 encoding OVA-AH1A5. Twelve days later, dye-labeled, peptide-pulsed target cells were transferred intravenously via the retroorbital sinus into immunized and untreated control mice. Target cells were prepared from naive splenocytes by lysing red cells by hypotonic shock, then splitting the cells into 3 populations that were pulsed with 1 µg/mL of either AH1 (SPSYVYHQF), AH1A5 (SPSYAYHQF), or negative control NY-ESO-181-88 (RGPESRLL) peptides. Cells were washed and then labeled with 2 μM CFSE (Invitrogen) plus one of 3 concentrations of Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen): 2, 0.2, or 0.02 μM. Target cells were combined at a 1:1:1 ratio and 5×106 total cells were transferred to recipients. The following day, spleens were harvested and the relative recovery of each population was compared between naive and immunized mice to calculate specific killing as previously described.17

CT26 Tumor Challenge

For prophylaxis experiments, BALB/c mice (10 per group) were immunized subcutaneously at the tail base with the indicated doses of ID-VP02 encoding OVA-AH1A5, which is a defined H-2Kb-restricted rejection epitope for CT26 tumor cells. Four weeks later, immunized and untreated control mice were injected subcutaneously with 8×104 CT26 tumor cells on the right flank. Tumor growth was monitored 3 times per week and mice were euthanized when tumor area exceeded 100 mm2. Experiments testing ID-VP02 in the therapeutic mode were performed the same way, with the exception that immunization with ID-VP02 was delayed until 4 days after tumor implantation.

RESULTS

Identification of the DC-SIGN Homolog SIGNR1 as a Murine Receptor for ID-VP02

While humans encode DC-SIGN and 1 paralog, DC-SIGNR, mice have 8 homologs of DC-SIGN (termed SIGNR1 through SIGNR8). Of these, 6 are predicted to be membrane bound, namely SIGNR1, SIGNR3, SIGNR4, SIGNR5, SIGNR7, and SIGNR8. On the basis of functional studies, SIGNR1, SIGNR3, and SIGNR5 (also referred to as murine DC-SIGN), are reported to be the closest functional orthologs of human DC-SIGN.18 We therefore tested the ability of the Sindbis virus envelope E1001 to mediate binding and entry via these receptors.

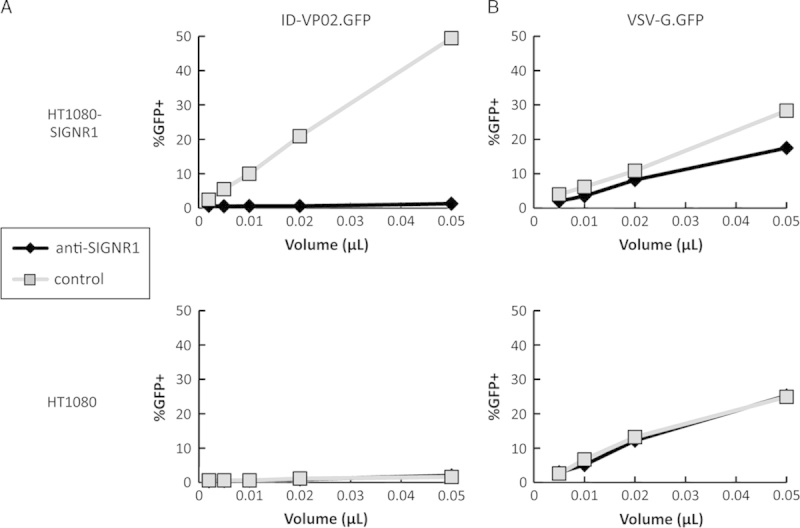

HT1080 cells stably expressing either mouse SIGNR1, SIGNR3, or SIGNR5 were generated (see Materials and methods section). Expression of the each receptor was confirmed by flow cytometry or RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A370). These cells were incubated with varying concentrations of integration-deficient GFP-encoding vector that was pseudotyped with Sindbis virus envelope E1001, kifunensine-modified high mannose E1001, or with pantropic VSV-G. In previous studies, we have established that the E1001 envelope produced in the presence of the mannosidase I inhibitor kifunensine is required for DC-SIGN binding and human DC transduction.6 In this experiment, therefore, HT1080 cells expressing human DC-SIGN were used as a positive control. Of the 3 mouse DC-SIGN orthologs tested, E1001-pseudotyped vector-transduced only mouse SIGNR1-expressing cells and did so in a kifunensine-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A371) and the ability of E1001-pseudotyped vector to transduce SIGNR1-expressing cells was completely blocked in the presence of an anti-SIGNR1 antibody (Fig. 1A). The transduction efficiency of kifunensine-modified E1001 vector on human DC-SIGN-expressing and mouse SIGNR1-expressing cells was comparable, indicating that SIGNR1 is a functionally orthologous receptor for ID-VP02 in the mouse.

FIGURE 1.

Antibody against SIGNR1 blocks transduction with ID-VP02. HT1080 cells expressing SIGNR1 (HT1080-SIGNR1) or the parental cells (HT1080) were preincubated with anti-SIGNR1 antibody (10 µg/mL) for 1 hour, after which increasing doses of (A) ID-VP02 or (B) VSV-G vectors encoding GFP were added. Transduction was assessed 72 hours later. Nevirapine was included on highest vector dose as a control for real transduction (data not shown). Vector titers of ID-VP02 and VSV-G were comparable (115 µg/mL p24, and 111 µg/mL p24, respectively).

SIGNR1 is Expressed on Mouse DCs In Vivo

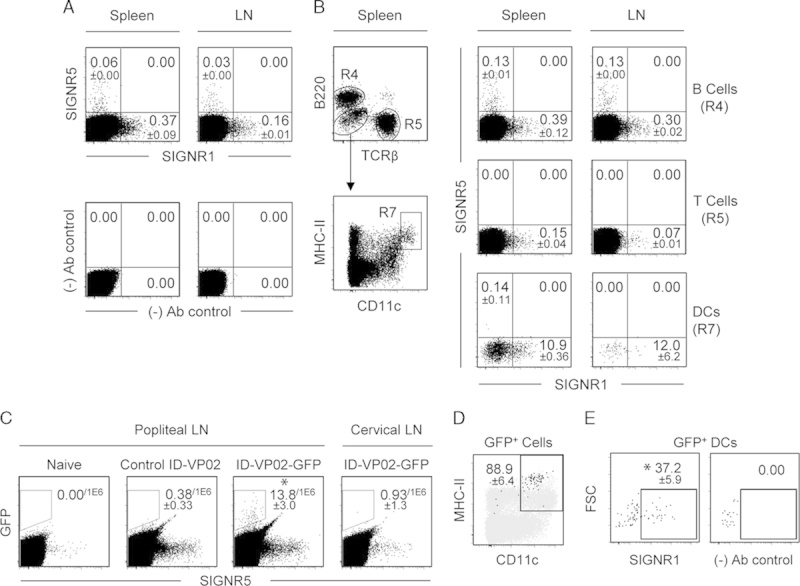

To further investigate the utility of the mouse model for functional studies with ID-VP02, we sought to establish whether SIGNR1 was expressed on mouse DCs. Single-cell suspensions from 3 individual spleens or 3 pools of 10 popliteal lymph nodes each were analyzed for SIGNR1 and SIGNR5 expression on T cells, B cells, and DCs. As previously reported,18 SIGNR5 expression was relatively rare in the steady state, being detected only on a small population of B cells (Figs. 2A, B). By contrast, although SIGNR1 expression was limited (<0.5%) on T and B cells, around 12% of MHC II+ CD11chi DCs expressed SIGNR1 (Fig. 2B). From an absolute numbers perspective, however, while DCs are clearly enriched for expression of SIGNR1, the majority of SIGNR1+ cells in the secondary lymphoid organs are actually lymphocytes, as DCs are relatively rare. With this characterization of the receptor distribution in mouse, we proceeded to evaluate whether ID-VP02 could transduce mouse DCs in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of mouse SIGNR1 and SIGNR5 and ID-VP02 transduction of dendritic cell (DC) in vivo. A, The expression of SIGNR1 and SIGNR5 on spleen and lymph cells was analyzed on live, single-cell events. Control staining pattern lacking SIGNR1-specific and SIGNR5-specific antibodies is shown (fluorescence minus two). B, Live, single-cell events from spleen and lymph node were subdivided into B cells (B220+ TCRβ−, labeled R4) and T cells (TCRβ+, B220−, labeled R5), and DCs (B220− TCRβ− MHC II+ CD11chi, labeled R7) and subsequently analyzed for expression of SIGNR5 and SIGNR1. For all subsets, frequencies of positive events were ≤0.00 in negative control stains lacking SIGNR1-specific and SIGNR5-specific antibodies (data not shown). C, Live, singlet events from the popliteal (draining) or cervical (nondraining) lymph nodes, not gated for any cellular markers, were analyzed for GFP expression. Lymph node cells were pooled from 5 mice, and 3 independent pools were analyzed. Popliteal lymph node cells from naive mice or mice injected with control vector served as negative controls. *P≤0.05 versus non–GFP-encoding control ID-VP02 (Mann-Whitney). D, Frequency of CD11c and MHC II on all GFP+ events, as identified in (C), from the popliteal lymph nodes of mice injected with GFP-encoding ID-VP02 are shown as black dots overlayed on total B220− TCRβ− events, shown in gray, as a reference. Gate values are the mean % CD11c+ MHC II+ of the GFP+ cells from 3 independent lymph node pools (5 donors each)±SD. E, Expression of SIGNR1 on GFP+ CD11c+ MHC II+ events, as identified in (D), is shown with (left panel) and without (fluorescence minus one, right panel) inclusion of SIGNR1-specific antibody. *P≤0.05 versus FMO control (Mann-Whitney). Gate statistics are the mean value±SD of 3 biological replicates. Values in (C) are number of positive events per 1×106 cells, whereas all other gate values are percentages.

ID-VP02 Targets Mouse Draining Lymph Node DCs In Vivo

The phenotype of GFP-expressing cells in the draining lymph node after subcutaneous injection with GFP-encoding ID-VP02 was analyzed by flow cytometry. Female BALB/c mice (15 per group) were injected subcutaneously in the footpad with 3×1010 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, control ID-VP02 encoding a nonfluorescent protein, or left untreated. Four days later, the popliteal and cervical lymph nodes were separately pooled from 5 mice (3 pools per treatment group) and analyzed for the presence of GFP-expressing cells. Injection of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, but not a control protein, led to detection of GFP+ cells in the draining popliteal but not in the distal lymph node (Fig. 2C). Notably, upon further surface marker analysis, approximately 90% of transduced cells were identified as DCs as indicated by CD11c and MHC II expression (Fig. 2D), despite the fact that the majority of the total SIGNR1-expressing cells per organ are actually T and B cells (data not shown). A likely explanation for this is that transduction occurs at the subcutaneous injection site, and DCs are selectively able to translocate to the draining LN. More than one third of the GFP+ DCs were SIGNR1+ (Fig. 2E), supporting a likely role for this receptor in mouse DC transduction in vivo. Whether the SIGNR1− DCs acquired GFP via SIGNR1-independent transduction or downregulated SIGNR1 after vector engagement is not entirely clear. Most importantly, however, these data confirmed that the mouse model was fitting to test the “on-target” immunologic activity of ID-VP02, with significant expression of the vector cargo in the desired target cell type enriched for the orthologous mouse receptor.

ID-VP02 has Limited Biodistribution in Mice

Although analysis of lymph node cells was consistent with specific targeting of mouse DCs in vivo, we performed biodistribution studies to establish whether transduction events could be detected in other, particularly nonlymphoid, tissues and to characterize the clearance kinetics at positive tissue sites. For this purpose, we utilized ID-VP02 encoding a polyepitope model antigen construct designated as LV1b (see Materials and methods section). After vector injection, the presence of reverse-transcribed vector genomes (vector DNA) can be measured by qPCR using a set of primers and probe specific for the LV1b cassette. C57BL/6 mice were administered 2.8×1010 vector genomes of ID-VP02-LV1b in a single subcutaneous injection at the base of the tail. On a timecourse between 1 and 42 days postinjection, vector DNA was quantified at the injection site (tail base), draining (inguinal), and nondraining (cervical) lymph nodes, spleen, heart, liver, brain, and ovaries. At early timepoints after administration, vector DNA was detected exclusively at the injection site and in the draining lymph node. The vector signal in these tissues decreased over time, with no quantifiable signal at 8 days in draining lymph node and signal barely above the limit of quantification (10 copies) at 42 days at the injection site (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A372). Similar peak and clearance kinetics were observed when BALB/c mice were utilized (data not shown). These results indicate that the dispersal of ID-VP02 outside the injection site is limited to the draining lymph node, where its biological activity would be hypothesized to occur.

To study potential off-target activity of the vector in human tissues, 12 primary human cell lines representative of different organ systems were incubated with ID-VP02.

ID-VP02 Shows no Off-Target Activity on a Panel of Primary Human Cells

Expression of transgene was detectable by RT-PCR only in DCs and not in other primary cells (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A373).

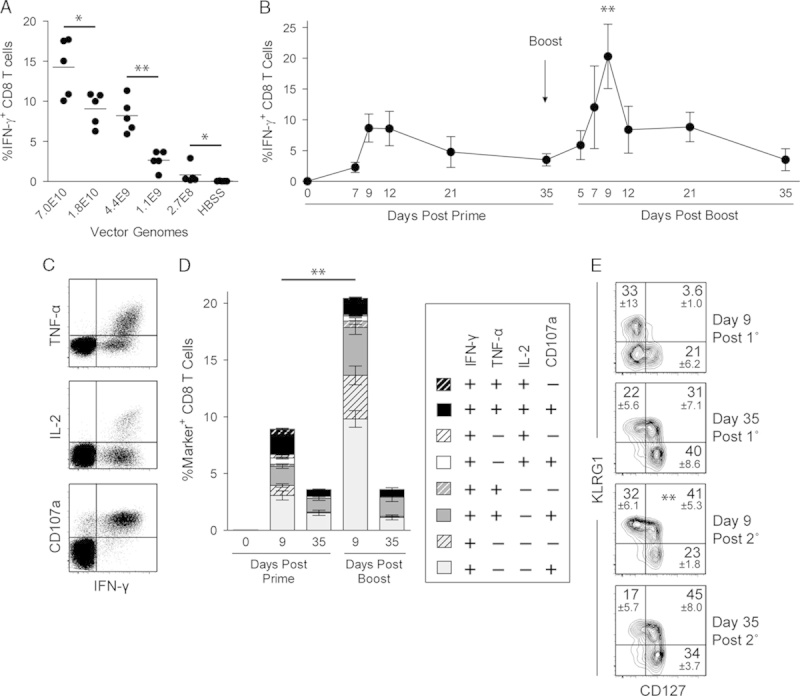

ID-VP02 Induces Polyfunctional Primary and Secondary CD8 T-Cell Responses

To assess the immunologic activity of ID-VP02 in vivo, a dose range of vector encoding full-length chicken ovalbumin (ID-VP02-OVA) was administered subcutaneously to C57BL/6 mice and the OVA257-specific CD8 T-cell response in the spleen was measured by ICS (Fig. 3A). The frequency of IFN-γ+ effectors among splenic CD8 T cells ranged from a mean of around 15% at a dose of 7.0×1010 vector genomes to around 1% at 2.7×108 vector genomes. CD8 T-cell responses against OVA were not induced by ID-VP02 encoding GFP (data not shown). In addition, the generation of OVA257-specific CD8 T-cell response by ID-VP02 was dependent on biologically active vector, as antigen-specific CD8 T-cell responses were not induced after heat inactivation (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A374). Collectively, these data indicate that ID-VP02 induces CD8 T-cell responses in a dose-dependent manner across the 2.5-log dose range that was investigated.

FIGURE 3.

ID-VP02 induces high-quality multifunctional primary CD8 T-cell responses that can be effectively expanded with a homologous boost. A, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with indicated doses (vector genomes) of ID-VP02 encoding full-length OVA or HBSS vehicle alone. At day 12 postimmunization, the percentage of OVA257-specific splenic CD8 T cells was measured by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS). B, The kinetics of the primary and secondary CD8 T-cell response to ID-VP02 encoding OVA was determined by immunizing mice (5 per group) with 1×1010 vector genomes of ID-VP02 in a prime-boost regimen with a 35-day interval and analyzing splenic CD8 T-cell responses at the indicated timepoints. Immunizations were staggered such that all groups were analyzed by ICS on the same day. Peak of the secondary response was significantly greater than the peak of primary response (**P≤0.01, Mann-Whitney). C, Representative intracellular IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2, and surface CD107a staining on viable CD8 T cells after peptide restimulation. D, Frequency of CD8 T cells expressing combinations of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and CD107a around the peak and postcontraction of the primary and secondary responses. Negligible numbers of CD8 T cells that were IFN-γ− expressed any other effector molecule. E, The effector/memory phenotype of CD44hi H-2Kb-OVA257 pentamer+ CD8 T cells was assessed by staining with CD127 and KLRG1 at the indicated timepoints. **Frequency of CD127+ KLRG1+ cells were significantly greater on day 9 post 2° than on day 9 post 1°. Gate values are mean±SD. *P≤0.05 and **P≤0.01 between indicated groups (Mann-Whitney).

To address whether priming with ID-VP02-induced memory T cells that could be recalled through the administration of ID-VP02 as a homologous boost, we primed animals with a dose of 1.0×1010 vector genomes and then boosted with an equivalent dose 35 days postprime. At various timepoints postprime and boost, the CD8 T-cell response was measured by ICS. By analyzing the frequency of IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells, we found that boosting with ID-VP02-OVA induced an OVA257-specific recall response that was both more rapid and of a >2-fold greater magnitude than the primary response (Fig. 3B). It is interesting to note that the contraction phase of the T-cell response after the prime was rather slow and had not returned to baseline after day 35.

In addition to staining for IFN-γ, the quality of the primary and secondary CD8 T-cell responses was analyzed by simultaneous staining for 2 additional cytokines, TNF-α and IL-2, as well as surface translocation of CD107a, a correlate of cytotoxic activity.19 After both the prime and boost, most of the responding CD8 T cells had a multifunctional phenotype as evidenced by elucidation of CD107a, TNF-α, and IL-2 (Fig. 3D). Notably, 35 days after the boost, essentially 100% of the IFN-γ+ cells were CD107a+, a majority also expressed TNF-α, and a substantial fraction of these “triple-positive” cells also produced IL-2, indicating the formation of memory T cells with high functional quality.

The markers KLRG1 and CD127, when measured around the peak of a virus-specific CD8 T-cell response, have been associated with a short-lived effector cell (SLEC) and memory precursor cell fates, respectively.20 As observed during infection with LCMV, when we analyzed the phenotype of antigen-specific H-2Kb-OVA257 multimer-binding CD8 T cells at day 9 postimmunization, a fraction of cells were polarized into either the KLRG1+ CD127− SLEC or KLRG1− CD127+ memory precursor cell phenotype (Fig. 3E). It is interesting to note that 35 days after both the prime and boost immunizations, although the majority of cells had CD127+ memory phenotype, they were roughly equally divided between KLRG1+ and KLRG1− subsets, both of which are reported to increased recall potential over SLEC.21

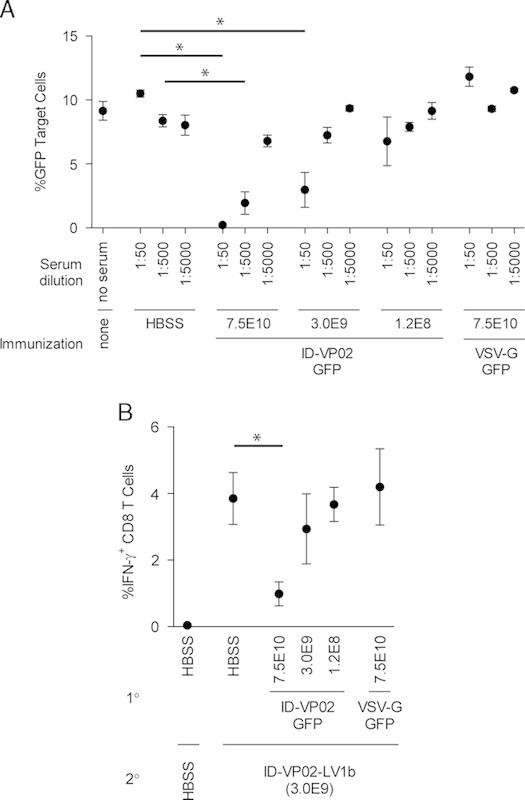

The data in Figure 3B indicate that ID-VP02 is effective when applied in a homologous prime-boost immunization regime. However, it is expected that a neutralizing antibody response would be generated against ID-VP02 after the first administration that could affect the potency of the vector for delivering antigen for presentation to CD8 T cells. To determine if neutralizing antibodies are generated against ID-VP02 after in vivo administration, serum was isolated from groups of 3 mice that had been immunized 28 days earlier with either 7.5×1010, 3.0×109, or 1.2×108 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, 7.5×1010 vector genomes of VSV-G pseudotyped lentivector encoding GFP, or with HBSS. The serum was then evaluated for the presence of neutralizing antibodies against ID-VP02 by in vitro transduction assay. Relative to serum from mice injected with HBSS or VSV-G pseudotyped control vector, serum from mice injected with either of the 2 higher doses of ID-VP02 was able to neutralize vector in this assay (Fig. 4A). The level of neutralization corresponded with the immunizing dose of ID-VP02 with higher doses of vector resulting in higher levels of neutralizing antibody titers. The neutralizing antibody response was specific to the Sindbis virus derived envelope of ID-VP02 in that no serum neutralization was observed from mice immunized with the VSV-G control vector at the highest vector dose (7.5×1010 vector genomes).

FIGURE 4.

Neutralizing antibody responses against ID-VP02 can be detected after immunization. A, Ten-fold dilutions of serum taken from mice 28 days after immunization with the indicated doses of ID-VP02 (ID-VP02-GFP), VSV-G pseudotyped vector (VSV-G-GFP), or HBSS, were preincubated with a reporter vector (ID-VP02 encoding GFP) for 1 hour. This serum-vector mix was then used as test article in a GFP transduction assay utilizing 293T.huDC-SIGN target cells. The percentage of GFP+ cells was analyzed 2 days posttransduction. The results are presented as mean±SD of 3 mice per group. B, Groups of mice were first immunized with either 7.5×1010, 3.0×109, or 1.2×108 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, 7.5×1010 vector genomes of VSV-G pseudotyped lentivector encoding GFP, or HBSS. On day 28 postprimary immunization the animals were immunized with 3.0×109 of ID-VP02 encoding an alternative antigen cassette, LV1b. OVA257-specific CD8 T-cell response in the spleen was measured by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) on day 12 after second immunization. *P≤0.05 between indicated groups (Mann-Whitney).

Because anti-ID-VP02 antibodies were detected in this assay, we wanted to determine if the level of neutralizing antibodies present in ID-VP02 immunized mice would have an affect on the in vivo potency of the vector. As the immunologic requirements to effectively prime naive CD8 T cells are much more stringent that those for boosting preexisting memory cells, we sought to determine what level of previous exposure to ID-VP02 (ie, dose) would be required to significantly impair the ability of a mid-range dose of ID-VP02 to prime naive CD8 T cells. Therefore, the mice described previously that had been immunized with either 7.5×1010, 3.0×109, or 1.2×108 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding GFP, 7.5×1010 vector genomes of VSV-G pseudotyped lentivector encoding GFP, or HBSS were immunized with 3.0×109 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding an alternative antigen cassette, termed LV1b, that encodes the minimal OVA257 peptide sequence. OVA257-specific CD8 T-cell response in the spleen was measured by ICS on day 12 postimmunization. Relative to the CD8 T-cell responses observed in mice injected with HBSS or VSV-G pseudotyped control vector, there was a clear reduction in the ability of 3.0×109 vector genomes of ID-VP02 to prime naive CD8 T-cell responses within the context of previous exposure to a 25-fold higher dose (7.5×1010 vector genomes) of ID-VP02 encoding GFP (Fig. 4B). However, this reduction was not observed in animals that had been preexposed to equal (3.0×109) or 25-fold lower (1.2×108) doses of ID-VP02-GFP. As in the in vitro neutralization assay, the mechanism responsible for the reduction in vector potency appeared to be specific to the envelope of ID-VP02 in that no reduction in priming of naive CD8 T cell was observed in mice previously immunized with 7.5×1010 vector genomes of VSV-G pseudotyped control vector. These data, in combination with the data demonstrating the absolute requirement for biologically active vector for naive CD8 T-cell priming to occur and the effectiveness of ID-VP02 in a homologous prime-boost immunization regime (Fig. 3B), indicate that although vector-specific immunity can be generated against ID-VP02 at high doses, the application of ID-VP02 is not limited to a single administration when equivalent mid-range doses are given for both the prime and boost immunizations.

Memory CD8 T Cells Induced by ID-VP02 Expand and Exhibit Antiviral Function

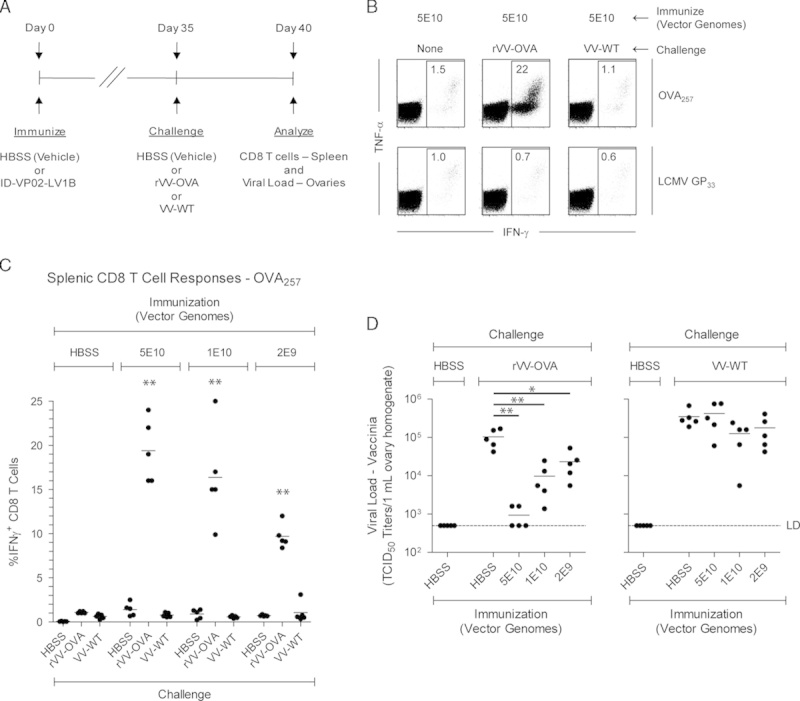

To directly evaluate the function of memory CD8 T cells induced by ID-VP02 immunization, we employed the LV1b antigen cassette, introduced earlier, that encodes both the minimal OVA257 and LCMV GP33 peptide sequences, 2 robust H-2Kb-restricted epitopes. As depicted schematically in Figure 5A, 35 days postimmunization with ID-VP02-LV1b, mice challenged with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing OVA (rVV-OVA), but not wild-type vaccinia virus (VV-WT), showed dramatic expansion of OVA257-specific CD8 T cells (Figs. 5B, C), indicating that these memory cells were recalled in an antigen-specific manner. Further, rVV-OVA did not expand GP33-specific memory cells (Fig. 5B), confirming the requirement for antigen specificity within the same animal. Corresponding to the dose-dependent induction of CD8 T cells that responded to infection, there was a clear dose-dependent reduction in the viral load of rVV-OVA in the ovaries of infected mice (Fig. 5D). Importantly, the sole antigenic sequence shared between the LV1b antigen construct and the rVV-OVA challenge strain was the SIINFEKL MHC class I epitope, indicating that the protection was mediated by CD8 T cells. Confirming that protection was indeed antigen specific, infection with VV-WT was not impacted by immunization.

FIGURE 5.

ID-VP02 immunization induces CD8 T cells that respond and provide protection against viral challenge. A, Experimental schedule. C57BL/6 mice (5 per group) were immunized with 5×1010, 1×1010, or 2×109 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding a polyepitope antigen (LV1b) that contains the H-2b-restricted OVA257 and LCMV GP33 CD8 T-cell epitopes and then challenged on day 35 postimmunization with 1×107 TCID50 wild-type WR-strain vaccine virus (VV-WT), WR-strain recombinant OVA vaccine virus (rVV-OVA), or left unchallenged. On day 40 (day 5 postchallenge) splenic CD8 T-cell responses and viral load in the ovaries were measured. B, OVA257-specific and LCMV GP33-specific CD8 T-cell responses were measured by staining for intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α after ex vivo peptide restimulation. Representative dot plots of the CD8 T-cell cytokine profile is shown. C, Frequency of OVA257-specific IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells in each animal. CD8 responses after rVV-OVA challenge were significantly greater in animals immunized ID-VP02 (any dose) compared with vehicle (**P≤0.01). D, Viral load (measured by TCID50 assay) within the ovaries of each animal. *P≤0.05 and **P≤0.01 between indicated groups (Mann-Whitney).

ID-VP02 Immunization Provides Both Prophylactic and Therapeutic Antitumor Efficacy

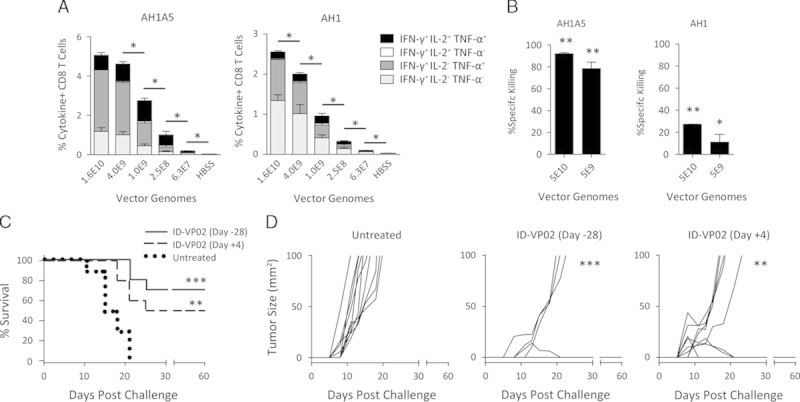

The CT26 tumor cell line is derived from a spontaneous colon carcinoma in BALB/c mice and an endogenous epitope that can mediate rejection of implanted CT26 tumors is the AH1 peptide. Although the MHC-TCR interaction is relatively weak with the AH1 epitope, the altered peptide ligand AH1A5 can stabilize this interaction, leading to greater CD8 T-cell expansion and antitumor responses.22 To generate ID-VP02 encoding this epitope, an antigen cassette was generated in which the AH1A5 sequence was inserted into full-length OVA sequence (OVA-AH1A5), as previously reported.23 When BALB/c mice were immunized with ID-VP02 encoding OVA-AH1A5, we observed dose-dependent induction of multifunctional AH1A5-specific CD8 T cells, approximately half of which cross-reacted with the endogenous AH1 sequence (Fig. 6A). The ability of ID-VP02-induced CD8 T cells to acquire cytolytic capacity was directly analyzed by in vivo cytotoxicity assay. Three splenocyte target cell populations were simultaneously labeled with CFSE plus varying concentrations of Cell Trace Violet, then pulsed with AH1, AH1A5, or a negative control peptide. Target cells were mixed at a 1:1:1 ratio, then cotransferred into recipient mice immunized 12 days earlier with ID-VP02 or left untreated. After 1 day, the relative recovery of AH1 and AH1A5 pulsed targets was reduced in ID-VP02 immunized mice, with specific killing rates over 90% against AH1A5 and about 25% against AH1 (Fig. 6B), indicating that ID-VP02 induces functional cytotoxic CD8 T cells against the immunizing antigen.

FIGURE 6.

Prophylactic and therapeutic antitumor efficacy following a single immunization with ID-VP02. A, BALB/c mice (5 per group) were immunized with indicated doses, in vector genomes, of ID-VP02 encoding AH1A5, a heteroclitic mutant of the endogenous CT26 tumor rejection epitope AH1, linked to OVA (OVA-AH1A5) or HBSS vehicle alone. At day 12 postimmunization, the percentage of AH1A5-specific or AH1-specific splenic CD8 T cells was measured by ICS. *P≤0.05 and between indicated groups (Mann-Whitney). B, Twelve days after immunization, a 1:1:1 mixture of dye-labeled target cells each pulsed with AH1, AH1A5, or a control peptide were transferred intravenously into immunized and naive mice (3 per group). The following day, spleens were harvested and the relative recovery of each population was compared between naive and immunized mice to calculate specific killing. *P≤0.05 and **P≤0.01 compared with naive (Mann-Whitney). C and D, BALB/c mice (10 per group) were injected subcutaneously with 8×104 CT26 tumor cells on the right flank and mice were euthanized when tumors exceeded 100 mm2. Mice were either left untreated, treated prophylactically 28 days before challenge with 4×109 vector genomes of ID-VP02 encoding OVA-AH1A5, or treated therapeutically 4 days postchallenge with the same dose of vector. Survival curves are shown in (C) and individual tumor growth curves are shown in (D). **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001 compared with untreated (Mantel-Cox).

As a first test for antitumor efficacy, mice immunized subcutaneously with ID-VP02-OVA-AH1A5 or vehicle were challenged 28 days later with CT26 tumor cells implanted in the flank. Whereas all control mice had lethal tumor growth (>100 mm2) by day 21, 70% of ID-ID-VP02-OVA-AH1A5 immunized mice were able to reject the implanted tumors and these surviving mice were tumor free for at least 60 days (Fig. 6C and data not shown). We extended these findings by applying ID-VP02 as a therapy to previously implanted CT26 tumors. In this model, tumors were allowed to grow for 4 days, and then animals were treated with the indicated doses of ID-VP02-OVA-AH1A5, or vehicle control. As in the prophylactic experiments, all control animals succumbed to tumor growth within approximately 3 weeks (Fig. 6D). By contrast, all mice treated with ID-VP02 encoding AH1A5 showed effects on tumor progression, ranging from a delay in the growth kinetics to outright rejection (Fig. 6D). Tumors either failed to grow to a palpable size (2/10) or completely regressed (3/10) in the immunized group, leading to 50% of the mice exhibiting no evidence of macroscopic disease out to at least day 60 (data not shown). By contrast, mice immunized with ID-VP02 encoding any irrelevant antigen showed no evidence of antitumor protection (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/JIT/A375). These data show that ID-VP02 can exert antitumor cytotoxic activity in both the prophylactic and therapeutic settings, supporting the evaluation of ID-VP02 as a therapeutic for cancer in humans.

DISCUSSION

Cytotoxic T cells are capable of eradicating established tumors as evidenced by the recent successes in cancer immunotherapy, notably adoptive T-cell therapy and immune checkpoint inhibition.24 As “master regulators of the immune response,” DCs are critical for the induction of cytotoxic CD8 T cells, which requires efficient antigen presentation, maturation of the DC, and costimulation of the T cell.1 To this end, ex vivo–generated DC-based vaccines have shown some promise in multiple clinical trials, however, their efficacy has been limited despite continued optimization of various vaccination parameters and logistical and cost issues of this approach have not been solved.25 In vivo targeting of tumor antigens to endocytic receptors of DCs results in enhanced cross-priming in the presence of a DC-maturing stimulus (eg, toll-like receptor agonist), and this concept is currently being explored in the clinic by fusing tumor antigens to antibodies specific for the lectin DEC-205.26,27 Preclinically, targeting antigens to DCs via antibodies directed to the lectins DC-SIGN and DNGR-1 (CLEC9 A) also resulted in enhanced CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses.28,29 However, the level of CD8 T-cell activation achieved by cross-presentation is lower than that typically observed with viral vectors, suggesting that effective MHC I presentation is better achieved through the processing and presentation of de novo expressed antigen.30,31

To this end, multiple recombinant viral vectors are currently in various stages of development as antigen-specific immunotherapies for cancer, including attenuated poxviruses, adenoviruses, and alphaviruses.32–35 None of these vectors targets DCs specifically, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of induction of neutralizing antibodies, packaging capacity, expression of viral proteins interfering with induction of immune responses or competing for T cells, as well as manufacturing issues. Taking into account that there are no data available comparing all vector platforms head-to-head and immune responses may vary depending on the antigens expressed, published results suggest that in mice the above vector system given as single immunization or homologous prime-boost regimen induce a lower frequency of antigen-specific T cells compared with that which we observed with a single injection of ID-VP02.19,34 ID-VP02 was highly effective at driving polyfunctional primary CD8 T-cell responses and stable CD8 T-cell memory populations that provided protective immunity against lethal vaccinia virus challenge. ID-VP02 was also effective at inducing secondary CD8 T-cell responses in a homologous prime-boost regimen. The observed boost of antigen-specific CD8 T cells upon vaccinia virus challenge also suggests that ID-VP02 could be used in a heterologous prime-boost regimen where a separate vector expressing a shared antigen is given as a secondary immunization, as in the case of the Prostvac vaccine.36 Impressively, however, OVA-specific responses induced by 2 immunizations with ID-VP02 appeared to be equivalent to responses induced by ID-VP02 prime and vaccinia boost, suggesting that even though antivector immune responses can be generated against the vector, ID-VP02 may be uniquely potent in the setting of homologous readministration.

In a cancer model, ID-VP02 expanded tumor-specific CD8 T cells that had a polyfunctional phenotype, mediated antigen-specific killing in vivo, and conferred both protective and therapeutic antitumor efficacy. Control of CT26 tumors was observed despite the observation that CD8 T cells primed by the AH1A5-altered peptide ligand showed limited cross-reactivity with the endogenous tumor sequence AH1. Furthermore, we have recently obtained evidence of therapeutic efficacy of ID-VP02 in the B16 mouse melanoma model. A clinical candidate expressing the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1 termed LV305 is currently in a phase I clinical trial (NCT02122861).

Although ID-VP02 was designed to transduce human DC via targeting of DC-SIGN and overcoming the SAMHD1-mediated restriction block via Vpx, we could establish the mouse as the preclinical model to establish safety and efficacy. Genomic analysis in mice has revealed a DC-SIGN cluster that contains 8 putative homologs to human DC-SIGN based on domain and sequence homologs.18 These are termed SIGNR1 through SIGNR8, with SIGNR5 often being referred to in the literature as mouse DC-SIGN. Functional studies based on carbohydrate binding have suggested that the closest functional orthologs to human DC-SIGN are SIGNR1, SIGNR3, and SIGNR5. In our studies, we found that of these only SIGNR1 functioned as a receptor for ID-VP02. It is interesting to note that, we found that expression of SIGNR1 and SIGNR5 were mutually exclusive in the mouse and, notably, that steady state lymph node–resident DCs preferentially expressed SIGNR1 and were targeted by ID-VP02. However, the fact that not all transduced lymph node–resident DCs expressed SIGNR1 may indicate that either receptor downregulation occurs, or other unknown receptors can be utilized for binding and entry. Pseudotyping of ID-VP02 with the envelope of vesicular stomatitis virus which has broad cellular tropism also resulted in strong immunogenicity,11 however, because the vector described here was designed to be specific for human DC, we have not performed head-to-head comparative efficacy studies in mice. Published results in mice suggest that direct expression of antigens in DC may be up to 100,000-fold more potent compared with cross-presentation with respect to activation of CD8 cells.31 Comparative data for DC-targeted and nontargeted vectors are not available from human studies.

In the biodistribution studies described here, reverse-transcribed vector-derived DNA was detected at high levels at the injection site 1 day after immunization with ID-VP02 and was progressively cleared over time to near background levels after 7 weeks. Vector DNA was also detected in the draining lymph node 1 and 4 days after injection and was cleared thereafter. Using GFP protein expression as a readout, we show that the majority of vector-transduced cells in the draining lymph node are DCs. Taken together, the findings from these studies are consistent with 2 vector biodistribution models, (1) direct access of the vector to the lymph node via the afferent lymph; and/or (2) transduction of tissue resident DCs at the injection site that subsequently migrate to the draining lymph node. Although the exact mechanism by which ID-VP02 is dispersed outside of the injection site to the draining lymph node cannot be elucidated with the data presented here, the results are consistent with the anticipated specificity of ID-VP02 for DCs and support its development as a clinical candidate for DC-targeted cancer immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R43AI087444-01 (S.H.R.).

J.M.O., B.K.-C., S.U.T., D.J.C., P.A.F., P.J.M., C.J.N., M.M.S., C.D.V., T.W.D., J.t.M., and S.H.R. are at least one of a current employee of Immune Design Corp. (IDC), a holder of stock and/or options in IDC, or an inventor on an issued patent or patent application for technology discussed in this paper which has been assigned to IDC. All the remaining authors have declared that there are no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website, www.immunotherapy-journal.com.

Present address: Jared M. Odegard, PhD, Benaroya Research Institute, 1201, 9th Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101.

Present address: Thomas W. Dubensky Jr, PhD, Aduro BioTech Inc., 626 Bancroft Way, #3C, Berkeley, CA 94710-2224.

Present address: Scott H. Robbins, PhD, Medimmune, Gaithersburg, Washington, DC.

Present address: Semih U. Tareen, PhD, Juno Therapeutics, 307 Westlake Ave N. Suite 300, Seattle, WA 98109.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mellman I. Dendritic cells: master regulators of the immune response. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity. 2013;39:38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu MA. Immunologic basis of vaccine vectors. Immunity. 2010;33:504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang L, Yang H, Rideout K, et al. Engineered lentivector targeting of dendritic cells for in vivo immunization. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breckpot K, Emeagi PU, Thielemans K. Lentiviral vectors for anti-tumor immunotherapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2008;8:438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tareen SU, Kelley-Clarke B, Nicolai CJ, et al. Design of a novel integration-deficient lentivector technology that incorporates genetic and posttranslational elements to target human dendritic cells. Mol Ther. 2014;22:575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyoshi H, Blomer U, Takahashi M, et al. Development of a self-inactivating lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1998;72:8150–8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayer M, Kantor B, Cockrell A, et al. A large U3 deletion causes increased in vivo expression from a nonintegrating lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1968–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, et al. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, et al. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;25:654–657, Tareen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tareen SU, Nicolai CJ, Campbell DJ, et al. A rev-independent gag/pol eliminates detectable psi-gag recombination in lentiviral vectors. Biores Open Access. 2013;2:421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kantor B, Bayer M, Ma H, et al. Notable reduction in illegitimate integration mediated by a PPT-deleted, nonintegrating lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2011;19:547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiskerchen M, Muesing MA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: effects of mutations on viral ability to integrate, direct viral gene expression from unintegrated viral DNA templates, and sustain viral propagation in primary cells. J Virol. 1995;69:376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotsopoulou E, Kim VN, Kingsman AJ, et al. A Rev-independent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-based vector that exploits a codon-optimized HIV-1 gag-pol gene. J Virol. 2000;74:4839–4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner R, Graf M, Bieler K, et al. Rev-independent expression of synthetic gag-pol genes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus: implications for the safety of lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:2403–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler SL, Hansen MS, Bushman. FD. A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wonderlich J, Shearer G, Livingstone A, Brooks A. Induction and measurement of cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2006, Chapter 3. Unit 3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powlesland AS, Ward EM, Sadhu SK, et al. Widely divergent biochemical properties of the complete set of mouse DC-SIGN-related proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20440–20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betts G, Poyntz H, Stylianou E, et al. Optimising immunogenicity with viral vectors: mixing MVA and HAdV-5 expressing the mycobacterial antigen Ag85A in a single injection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, et al. 2003. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obar JJ, Jellison ER, Sheridan BS, et al. Pathogen-induced inflammatory environment controls effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4967–4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slansky JE, Rattis FM, Boyd LF. Enhanced antigen-specific antitumor immunity with altered peptide ligands that stabilize the MHC-peptide-TCR complex. Immunity. 2000;13:529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brockstedt DG, Giedlin MA, Leong ML, et al. Listeria-based cancer vaccines that segregate immunogenicity from toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13832–13837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wimmers F, Schreibelt G, Sköld AE, et al. Paradigm shift in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy: from in vitro generated monocyte-derived DCs to naturally circulating DC subsets. Front Immunol. 2014;5:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonifaz LC, Bonnyay DP, Charalambous A, et al. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med. 2004;199:815–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhodapkar MV, Sznol M, Zhao B, et al. Induction of antigen-specific immunity with a vaccine targeting NY-ESO-1 to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205. Sci Transl Med. 2014;16:232ra51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hesse C, Ginter W, Förg T, et al. In vivo targeting of human DC-SIGN drastically enhances CD8+ T-cell-mediated protective immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:2543–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Picco G, Beatson R, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, et al. Targeting DNGR-1 (CLEC9A) with antibody/MUC1 peptide conjugates as a vaccine for carcinomas. Eur J Immunol. 2014;1947:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu RH, Remakus S, Ma X, et al. Direct presentation is sufficient for an efficient anti-viral CD8+ T cell response. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinkernagel RM. On the role of dendritic cells versus other cells in inducing protective CD8+ T cell responses. Front Immunol. 2014;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gómez CE, Perdiguero B, García-Arriaza J, et al. Clinical applications of attenuated MVA poxvirus strain. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2013;12:1395–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madan RA, Bilusic M, Heery C, et al. Clinical evaluation of TRICOM vector therapeutic cancer vaccines. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majhen D, Calderon H, Chandra N, et al. Adenovirus-based vaccines for fighting infectious diseases and cancer: progress in the field. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25:301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avogadri F, Zappasodi R, Yang A, et al. Combination of alphavirus replicon particle-based vaccination with immunomodulatory antibodies: therapeutic activity in the b16 melanoma mouse model and immune correlates. Cancer Immunol Res. 2104;2:448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulley JL1, Madan RA, Tsang KY, et al. Immune impact induced by PROSTVAC (PSA-TRICOM), a therapeutic vaccine for prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:133–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.