Abstract

The autophagy inhibitors chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) have single agent antiproliferative activity against human cancer cell lines; however, low potency may limit their antitumor efficacy clinically. We synthesized a series of chloroquine analogs that retained the 4-aminoquinoline subunit and incorporated different substituted triazoles into the target structure. These compounds were tested for growth inhibition against H460 and HCC827 human lung cancer and BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells. The most potent compound, EAD1, had an IC50 of 5.8 μM in the BxPC3 cells and was approximately 8-fold more potent than CQ and HCQ. EAD1 inhibited autophagy, as judged by the cellular accumulation of the autophagy-related autophagosome proteins LC3-II and p62 and induced apoptosis. The increases in LC3-II levels by the analogues were highly correlated with their growth inhibitory IC50s, suggesting that autophagy blockade is closely linked to inhibition of cell proliferation. EAD1 is a viable lead compound for evaluation of the antitumor activity of autophagy inhibitors in vivo.

Keywords: Autophagy, click chemistry, chloroquinoline triazoles, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer

Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy) is an evolutionarily conserved, regulated catabolic process that degrades cellular proteins and organelles, allowing the recycling of their biochemical components for use in energy production and biosynthetic reactions.1−3 Autophagy has a role in a number of critical cell functions, including stress response, cellular quality control, tissue homeostasis, and energy production. Autophagy proceeds at a low basal level in all cells, where it is used to remove damaged proteins and organelles, particularly mitochondria, whose intracellular accumulation would be toxic. Depending on the tissue type and developmental stage, autophagy has both pro- and antisurvival effects, and its role in cancer is also contextual.3−6 In tumorigenesis, autophagy can suppress the initiation and development of early tumors, and the loss or inhibition of autophagy promotes aneuploidy and the development of the transformed phenotype.7−10 However, in established tumors, inhibition of autophagy causes tumor regression, suggesting that the autophagic process provides a survival advantage to tumors, and acts as a mechanism for overcoming stress during oncogenesis.6,10−12

Increased autophagic flux and elevated punctate expression of the autophagy-associated protein LC3 was found in a large majority of human tumors, compared to nonmalignant tissue, and was associated with increased tumor proliferation, invasion and metastasis, and shorter patient survival.13 A detailed mechanistic study found that autophagy has a critical role in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) pathogenesis, where it is expressed at high basal levels in the later stages of transformation and is required for continued malignant growth in vitro and in vivo.(6,10) As the PDAC cells are dependent on autophagy, genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of autophagy leads to significant growth suppression in vitro and to a robust tumor regression and prolonged survival in pancreatic cancer xenografts and genetic mouse models.

Similarly, studies in a mouse genetic model of oncogenic K-Ras-induced lung cancer reported dramatic tumor regressions when autophagy was ablated genetically in the tumor.11 In this model, knockout of the autophagy gene atg-7 caused the regression of lung adenocarcinomas to benign oncocytomas, with eventual tumor disintegration.11 In a follow-up study, profound regression of advanced lung adenocarcinomas was observed when atg-7 expression and autophagy was shut-off in the entire mouse.12 This latter study provides preclinical proof of the principle that strategies to systemically inhibit autophagy may be therapeutically effective in lung cancer.2 In addition to lung and pancreatic cancers, autophagy inhibitors have single agent antiproliferative effects in vitro and in mice on a variety of neoplastic cells, including melanoma, glioma, lymphoma, colon, and breast cancer cells.11−18

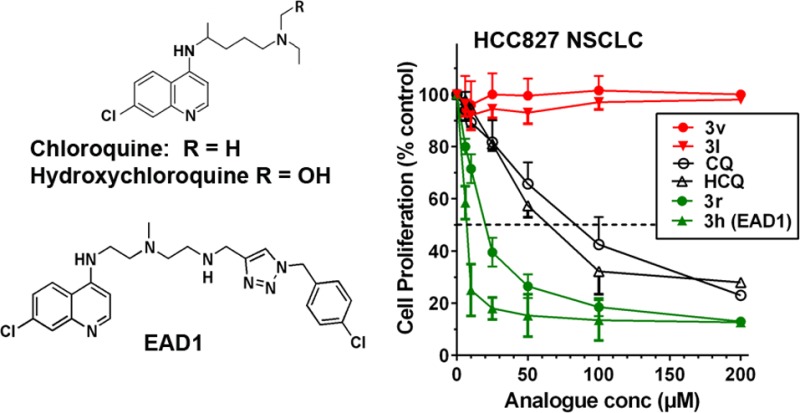

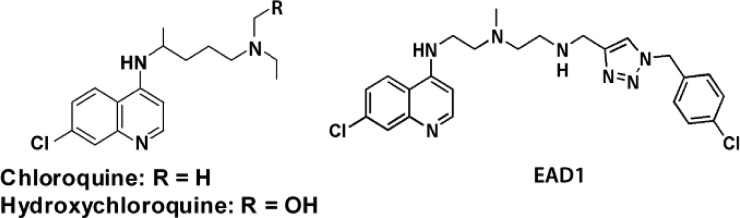

Autophagy is dramatically increased during starvation, and many reports have described a similar upregulation in tumor cells in response to chemotherapeutic agents, including cytotoxic drugs, targeted agents, and radiation.1,5,19 This upregulation has been shown to be a mechanism of drug resistance, and the use of autophagy inhibitors, including chloroquine (CQ) or hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (Figure 1), can reverse this effect.

Figure 1.

Structure of chloroquine (CQ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and the lead compound, EAD1 (3h).

While most reports have found that autophagy inhibition restores and/or enhances the sensitivity of the tumor cells to chemotherapy, as in tumorigenesis, the consequences of drug-induced autophagy induction might be context-dependent.20 Nevertheless, there is an increasing appreciation that autophagy inhibitors used either as single agents or in combination with other anticancer drugs, could be a viable therapeutic approach to cancer treatment.

While CQ and HCQ are effective inhibitors of autophagy in vitro, their in vivo efficacy may require concentrations at the upper range of tolerability.21,22 For example, a recent phase I trial of HCQ in solid tumor patients used population pharmacokinetic modeling and found that the peak whole blood concentrations (Cmax) of HCQ averaged approximately 7 μM with daily dosing of 1200 mg, the highest dose tested.23 In contrast, the IC50s for growth inhibition by HCQ ranged from 16 to 42 μM in a series of tumor cell lines.17,18 Thus, the low potency of CQ and HCQ may limit their efficacy in vivo, and it is uncertain if levels of HCQ that cause sufficient and sustained inhibition of autophagy will be achieved in the large number of current clinical trials.

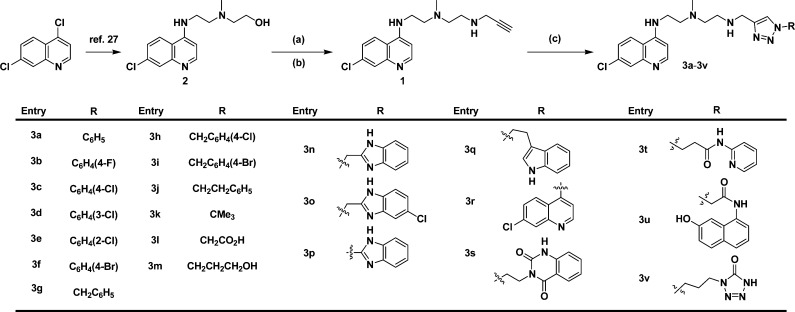

To address the limitations of the current autophagy inhibitors, we synthesized a series of compounds that retained the 4-aminoquinoline subunit. Copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) was used to incorporate substituted triazoles into the parent structure to form a library of novel autophagy inhibitors with increased potency, compared to CQ and HCQ. The synthesis was based on the alkyne 1 (Scheme 1) and late stage diversification by triazole formation with a wide range of substituted azides.24−26 Alkyne 1 was readily prepared from known alcohol 2.27 Chlorination was achieved by treatment with thionyl chloride, and the chloride was then displaced with propargylamine. Finally, triazoles 3a–3v were prepared by CuAAC reaction with azides corresponding to 3a–3v. The symmetrical analogue 5 was prepared from dipropargylamine and azide corresponding to 3r (Scheme 2A). Truncated analogues 6a–6b were prepared in analogy with compounds 3 (Scheme 2B).

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route to Triazole-Containing CQ Analogues.

Reagents and conditions: (a) SOCl2, PhMe (89%); (b) propargylamine, NaI, DMF (66%); (c) azides corresponding to 3a–3v, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate (20–79%).

Scheme 2. Synthetic Route to Truncated Analogues.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate (53%); (b) propargylamine (6a) or N-methylpropargylamine (6b), Et3N, THF (52% for 6a; 49% for 6b); (c) CuSO4, sodium ascorbate (60% for 6a; 65% for 6b).

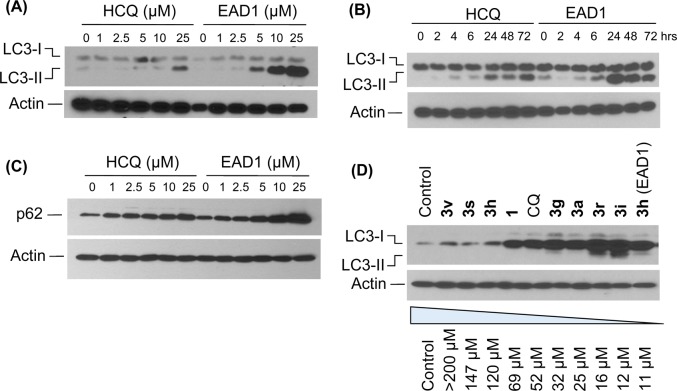

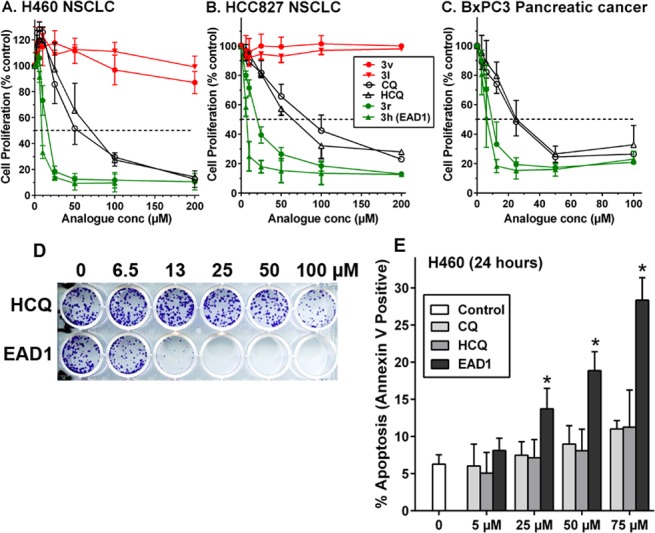

All compounds were tested for growth inhibitory activity in three human cancer cell lines, H460 and HCC827 nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells. The compounds were tested over a 100-fold concentration range with treatment for 72 h, and IC50s were calculated (Figure 2). Representative growth inhibition curves are shown in Figure 2A–C, illustrating the effects of CQ, HCQ, two inactive analogues, 3v and 3l, and two analogues with increased potency compared to CQ and HCQ, 3r and 3h (EAD1). Approximately half of the synthesized compounds were more potent than CQ and HCQ, and all compounds showed similar effects on all three cell lines (Table 1). The most active compound, 3h (EAD1) (4-chlorophenyl triazole polyamine chloroquinoline; Figure 1), had IC50s of 11, 7.6, and 5.8 μM against the H460, HCC827, and BxPC3 cells, respectively, and was on average 7-fold more potent than HCQ. Concentrations of EAD1 above 25 μM caused nearly complete cell death at 72 h.

Figure 2.

Growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis by chloroquine (CQ), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and the indicated compounds. A–C: Human nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and pancreatic cancer cells were treated for 72 h at the indicated concentrations and cell numbers quantified with SRB assays. Data are means ± SD of at least 3 experiments, each done in triplicate. D: H460 cells were treated with HCQ or EAD1 for 24 h. Drug-containing medium was replaced with drug-free medium, and colonies were stained with crystal violet after an additional 10 days. E: Apoptosis was determined in CQ, HCQ, and EAD1-treated H460 cells by incubation with APC-conjugated annexin V and flow cytometry. Values are means ± SD of 3 experiments. *Indicates significantly different from Control, CQ, and HCQ, p < 0.05.

Table 1. Growth Inhibition by Chloroquinoline Triazolesa.

| IC50 (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | H460 | HCC827 | BxPC3 | potencyb (relative to HCQ) |

| 3h (EAD1) | 11 | 7.6 | 5.8 | 7.0 ± 1.4 |

| 3q | 12 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 6.0 ± 1.7 |

| 3i | 12 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 5.7 ± 1.7 |

| 3c | 14 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 5.2 ± 1.6 |

| 3f | 15 | 11 | 7.9 | 5.0 ± 1.0 |

| 3d | 17 | 9.4 | 12 | 4.7 ± 2.0 |

| 3e | 20 | 12 | 11 | 4.0 ± 1.2 |

| 3r | 16 | 18 | 8.8 | 3.9 ± 0.6 |

| 3j | 24 | 15 | 13 | 3.2 ± 0.9 |

| 6a | 21 | 16 | 14 | 3.2 ± 0.9 |

| 3g | 32 | 16 | 9.7 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| 3a | 25 | 26 | 10 | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| 3b | 34 | 19 | 12 | 2.8 ± 0.6 |

| 6b | 29 | 18 | 16 | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| 3p | 33 | 32 | 16 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| CQ | 52 | 76 | 25 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| HCQ | 74 | 65 | 33 | 1.0 |

| 3k | 79 | 56 | 39 | |

| 3o | 59 | 65 | 44 | |

| 5 | 70 | 72 | 78 | |

| 3u | 67 | 86 | ||

| 1 | 69 | 105 | ||

| 3n | 120 | 164 | ||

| 3s | 147 | >200 | ||

| 3v | >200 | >200 | ||

| 3t | >200 | >200 | ||

| 3l | >200 | >200 | ||

| 3m | >200 | >200 | ||

Antiproliferative activity was measured using SRB assays. Cells were treated with compounds for 72 h. Results are means of at least 3 experiments, each done in triplicate.

Potency was calculated as the ratio of IC50 for each compound relative to the IC50 of HCQ; data are means ± SEM for all 3 cell lines.

Growth inhibition by EAD1 (3h) was also demonstrated when the cells were treated with the drugs for 24 h, and then allowed to form colonies in drug-free medium for 10 days. As shown in Figure 2D, EAD1 was greater than 10-fold more potent than HCQ in this assay. EAD1 induced apoptosis in the H460 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, as assessed by the detection of cell surface phosphatidylserine, a marker of early apoptosis, by fluorescently labeled annexin V (Figure 2E). Apoptosis induced by EAD1 was significantly greater than that induced by CQ and HCQ at drug concentrations of 25, 50, and 75 μM.

While comparing the potency of the analogues, we noticed some trends in the structure–activity relationship: compounds with halogenated benzyl or phenyl N-substituents on the triazole were generally the most potent (e.g., 3h, 3i, 3c, etc.). Only minor differences between bromine and chlorine substituents were observed, but fluorine-containing analogues exhibited diminished activity. ortho-, meta-, and para-Cl substituents showed similar potency (3c, 3d, and 3e). Compound 3q showed good activity; heteroaromatic substituents were generally less potent. Aliphatic substituents on the triazole, 3k, 3l, and 3m, led to significant loss of activity. A three atom truncation of the spacer unit (compare 3r and 6b) also resulted in reduced potency. Finally, all compounds lacking the triazole-unit were very poor inhibitors, and introduction of a second triazole (14–04, 5) was also found to be detrimental to inhibitory activity.

Chloroquine is a diprotic weak base, and in cells, it is concentrated in the acidic environment of lysosomes, as predicted by its pKs (8.1 and 10.1), where it elevates lysosomal pH through its actions as a tertiary amine.28,29 Examination of their chemical structures suggests it is unlikely that differential effects on lysosomal pH can account for the potencies of the compounds, as the most potent compound (3h) and the weakest inhibitor (3m) have very similar basicity (chlorobenzyl vs propanol side chains), yet their inhibitory activities were remarkably different.

Autophagy is a dynamic multistep process, which is initiated when a portion of the cytoplasm containing the intended cargo is sequestered in a double membrane vesicle that eventually closes to form an autophagosome.2−4 The outer membrane of the autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome, and the inner material is degraded by lysosomal enzymes, which are then recycled into the cell. Several proteins, known as atg proteins, are required for the various steps in the formation of the autophagosome. One of these proteins, the mammalian homologue of atg8, is also known as the microtubule-associated light chain 3 (LC3). LC3 is a widely used marker of autophagy, as it is either in a free cytoplasmic form (LC3-I) or as a lipidated form inserted into the inner and outer membranes of the autophagosome (LC3-II). HCQ and CQ inhibit the autophagic process at a late stage, leading to the accumulation of autophagosomes and an increase in LC3-II in treated cells.

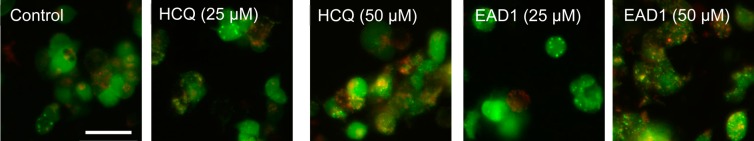

We evaluated the ability of EAD1 to inhibit autophagy by measuring autophagosome levels in lung cancer cells using a mCherry-GFP tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3B reporter protein.30 When LC3 is localized on the autophagosome membrane, the mCherry-GFP-LC3 forms fluorescent puncta. As seen in Figure 3, few control cells had punctate signals, and most cells had a diffuse LC3 expression. Both HCQ and EAD1 increased the punctate LC3 signal, with a larger increase seen in EAD1-treated cells than for HCQ at the two concentrations tested.

Figure 3.

HCQ and EAD1 increase punctate LC3 expression in lung cancer cells. H3122 NSCLC cells were transfected with an LC3-expressing vector (mCherry-EGFP-LC3B). Transfected cells were treated with HCQ or EAD1 at the indicated concentrations for 6 h, fixed, and analyzed by fluorescent microscopy. Increases in green, red, and yellow fluorescent puncta were seen with drug treatment. Size bar = 50 μm.

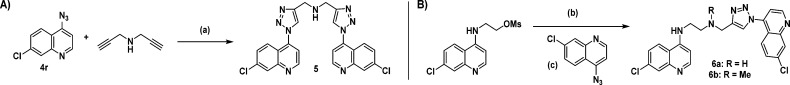

LC3 levels were also evaluated by immunoblot of drug-treated H460 cells, which allows for the distinction between cytoplasmic LC3-I and autophagosome-bound LC3-II.31 While both HCQ and EAD1 caused concentration and time-dependent increases in LC3-II levels (Figure 4A,B), the increase was larger at each concentration for EAD1 than for HCQ. The effect of 25 μM HCQ on LC3-II was approximately equal to that of 5 μM EAD1 (Figure 4A). The effects of HCQ and EAD1 were also compared on a second autophagy-associated protein, p62, a substrate of the autophagic process that is selectively incorporated into autophagosomes through direct binding to LC3 and is efficiently degraded by autophagy.31 Inhibition of autophagy would be anticipated to lead to the accumulation of p62, and this was observed in a concentration-dependent manner with both HCQ and EAD1, although as with LC3-II, EAD1 had a more potent effect than did HCQ (Figure 4C). To determine if the inhibition of autophagy was related to the growth inhibitory effect of the compounds, we treated cells with a group of the compounds, which were selected to encompass the range of activity observed. As shown in Figure 4D, the extent of LC3-II accumulation was closely linked to the corresponding compound’s IC50, such that compounds with little or no antiproliferative activity (3s and 3v) did not cause an increase in LC3-II, while the most active compounds (3h, 3i, and 3r) produced the largest increase. There was a high degree of correlation between the inhibition of autophagy and a compound’s potency as an inhibitor of cell growth, consistent with the hypothesis that growth inhibition was a consequence of the inhibitory effect on autophagy.

Figure 4.

Increase in autophagosome-associated proteins with treatment with HCQ and EAD1 (3h). H460 cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of HCQ and EAD1 (3h) (A,C) or for the indicated times with 10 μM compound (B). In panel (D), cells were treated with the indicated compounds (10 μM for 24 h). The IC50 values for the inhibition of proliferation for each compound are shown. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblots with antibodies to LC3 (A,B,D) or p62 (C). Blots were also probed for actin.

While there has been extensive exploration of the antimalarial activity of various chloroquine analogues, few studies have focused on identifying novel compounds with anticancer activity. In three such reports, a dimeric analogue of CQ (Lys05) inhibited glioma, melanoma, and colon cancer cells with IC50s of 3.6 to 6 μM, while an antischistosome drug, lucanthone, inhibited breast cancer cell lines with IC50s of 5.7 to 8.7 μM.17,32 Similar to our experiments, Lys05 and lucanthone increased expression of LC3-II and p62 and induced apoptosis. Lys05 also inhibited tumor xenograft growth.17 A series of 4-aminoquinoline analogues with halogen and side chain substitutions inhibited breast cancer cell growth with IC50s as low as 4.3 μM.18 Notable in the latter report was the selective cell-killing effect the analogues had toward tumor cells, when compared to a matched noncancer cell line.18 The active compounds identified in the present study have potencies comparable to the compounds in these reports.

In conclusion, a series of triazole-functionalized chloroquinoline derivatives were synthesized and tested against three cancer cell lines. The degree of induction of autophagy across the series of compounds was closely correlated with antiproliferative effects. Compound EAD1 had increased growth inhibitory and autophagy-inducing potencies compared to CQ and HCQ. EAD1 is a viable lead compound for evaluation of the antitumor activity of autophagy inhibitors in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ana Maria Cuervo for the mCherry-EGFP-LC3B vector and Hillah Douster for technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CuAAC

copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition

- CQ

chloroquine

- HCQ

hydroxychloroquine

- LC3

microtubule-associated light chain 3

- NSCLC

nonsmall cell lung cancer

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Supporting Information Available

Compound characterization and methods for syntheses and biological studies. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

§ These authors contributed equally to this work.

This research was supported in part by grants R01-CA163907 (to E.L.S.) and R01-GM093282 (to P.W.) from the NIH, and the CTSA Grants UL1 TR001073, TL1 TR001072, and KL2 TR001071 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Amaravadi R. K.; Lippincott-Schwartz J.; Yin X. M.; Weiss W. A.; Takebe N.; Timmer W.; DiPaola R. S.; Lotze M. T.; White E. Principles and current strategies for targeting autophagy for cancer treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 654–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M.; Thompson C. B. Autophagy: basic principles and relevance to disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 427–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B.; Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008, 132, 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmelman A. C. The dynamic nature of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E.; DiPaola R. S. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5308–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Wang X.; Contino G.; Liesa M.; Sahin E.; Ying H.; Bause A.; Li Y.; Stommel J. M.; Dell’antonio G.; Mautner J.; Tonon G.; Haigis M.; Shirihai O. S.; Doglioni C.; Bardeesy N.; Kimmelman A. C. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 717–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R.; Karp C. M.; Beaudoin B.; Vuong N.; Chen G.; Chen H. Y.; Bray K.; Reddy A.; Bhanot G.; Gelinas C.; et al. Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell 2009, 137, 1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X. H.; Jackson S.; Seaman M.; Brown K.; Kempkes B.; Hibshoosh H.; Levine B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999, 402, 672–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A.; Komatsu M.; Hara T.; Sakamoto A.; Kishi C.; Waguri S.; Eishi Y.; Hino O.; Tanaka K.; Mizushima N. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A.; Rajeshkumar N. V.; Wang X.; Yabuuchi S.; Alexander B. M.; Chu G. C.; Von Hoff D. D.; Maitra A.; Kimmelman A. C. Autophagy is critical for pancreatic tumor growth and progression in tumors with p53 alterations. Cancer Discovery 2014, 4, 905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. Y.; Karsli-Uzunbas G.; Mathew R.; Aisner S. C.; Kamphorst J. J.; Strohecker A. M.; Chen G.; Price S.; Lu W.; Teng X.; Snyder E.; Santanam U.; Dipaola R. S.; Jacks T.; Rabinowitz J. D.; White E. Autophagy suppresses progression of K-ras-induced lung tumors to oncocytomas and maintains lipid homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1447–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsli-Uzunbas G.; Guo J. Y.; Price S.; Teng X.; Laddha S. V.; Khor S.; Kalaany N. Y.; Jacks T.; Chan C. S.; Rabinowitz J. D.; White E. Autophagy is required for glucose homeostasis and lung tumor maintenance. Cancer Discovery 2014, 4, 914–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazova R.; Camp R. L.; Klump V.; Siddiqui S. F.; Amaravadi R. K.; Pawelek J. M. Punctate LC3B expression is a common feature of solid tumors and associated with proliferation, metastasis, and poor outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 370–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo J.; Briceño E.; López-González M. A. Adding chloroquine to conventional treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Int. Med. 2006, 144, 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y.; Matsukuma S.; Nakamura Y.; Yoshihara M.; Koizume S.; Sekiguchi H.; Saito H.; Nakayama H.; Kameda Y.; Yokose T.; Oguni S.; Niki T.; Miyagi Y. Enhanced autophagy is required for survival in EGFR-independent EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma cells. Lab Invest. 2013, 93, 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi R. K.; Yu D.; Lum J. J.; Bui T.; Christophorou M. A.; Evan G. I.; Thomas-Tikhonenko A.; Thompson C. B. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2007, 117, 326–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAfee Q.; Zhang Z.; Samanta A.; Levi S. M.; Ma X. H.; Piao S.; Lynch J. P.; Uehara T.; Sepulveda A. R.; Davis L. E.; Winkler J. D.; Amaravadi R. K. Autophagy inhibitor Lys05 has single-agent antitumor activity and reproduces the phenotype of a genetic autophagy deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 8253–8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon V. R.; Hu C.; Lee H. Design and synthesis of chloroquine analogs with anti-breast cancer property. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 3916–3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja Solomon V.; Lee H. Chloroquine and analogs: a new promise of an old drug for effective and safe cancer therapies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 625, 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz D. A. The four faces of autophagy: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster T.; Gibbs J. P.; Shen D.; Baethge B. A.; Botstein G. R.; Caldwell J.; Dietz F.; Ettlinger R.; Golden H. E.; Lindsley H.; McLaughlin G. E.; Moreland L. W.; Roberts W. N.; Rooney T. W.; Rothschild B.; Sack M.; Sebba A. I.; Weisman M.; Welch K. E.; Yocum D.; Furst D. E. Hydroxychloroquine concentration-response relationships in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 1460–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S. B.; Supko J. G.; Neal J. W.; Muzikansky A.; Digumarthy S.; Fidias P.; Temel J. S.; Heist R. S.; Shaw A. T.; McCarthy P. O.; Lynch T. J.; Sharma S.; Settleman J. E.; Sequist L. V. A phase I study of erlotinib and hydroxychloroquine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 1602–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala R.; Leone R.; Chang Y. C.; Fecher L.; Schuchter L.; Kramer A.; Tan K. S.; Heitjan D. F.; Rodgers G.; Gallagher M.; Piao S.; Troxel A.; Evans T.; Demichele A.; Nathanson K. L.; O’Dwyer P. J.; Kaiser J.; Pontiggia L.; Davis L. E.; Amaravadi R. K. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense Temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1369–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Hong S.; Tran A.; Jiang H.; Triano R.; Liu Y.; Chen X.; Wu P. Sulfated ligands for the Copper(I)-catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition. Chem.—Asian J. 2011, 10, 2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V.; Green L. G.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective ″ligation″ of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano del Amo D.; Wang W.; Jiang H.; Besanceney C.; Yan A. C.; Levy M.; Liu Y.; Marlow F. L.; Wu P. Biocompatible copper(I) catalysts for in vivo imaging of glycans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16893–16899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukulula M.; Sharma R.-K.; Meurillon M.; Mahajan A.; Naran K.; Warner D.; Huang J.; Mekonnen B.; Chibale K. Synthesis and antiplasmodial and antimycobacterial evaluation of new nitroimidazole and nitroimidazooxazine derivatives. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 128–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad D. J.; Schlesinger P. H.; Gluzman I. Y. The specificity of chloroquine. Parasitol. Today 1992, 8, 183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C.; de Barsy T.; Poole B.; Trouet A.; Tulkens P.; Van Hoof F. Commentary. Lysosomotropic agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974, 23, 2495–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S.; Noda T.; Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter gene, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 2007, 3, 452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N.; Yoshimori T.; Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 2010, 140, 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carew J. S.; Espitia C. M.; Esquivel J. A. III; Mahalingam D.; Kelly K. R.; Reddy G.; Giles F. J.; Nawrocki S. T. Lucanthone is a novel inhibitor of autophagy that induces cathepsin D-mediated apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 6602–6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.