Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents approximately 80% of all lung cancers. Unfortunately, at their time of diagnosis, most patients have advanced to unresectable disease with a very poor prognosis. The oriental herbal medicine HangAm-Plus(HAP) has been developed for antitumor purposes, and several previous studies have reported its therapeutic effects. In this study, the efficacy of HAP was evaluated as a third-line treatment for advanced-stage IIIb/IV NSCLC.

Methods:

The study involved six patients treated at the East- West Cancer Center (EWCC) from April 2010 to October 2011. Inoperable advanced-stage IIIb/IV NSCLC patients received 3,000 or 6,000 mg of HAP on a daily basis over a 12-week period. Computed tomography (CT) scans were obtained from the patients at the time of the initial administration and after 12 weeks of treatment. We observed and analyzed the patients overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results:

Of the six patients, three expired during the study, and the three remaining patients were alive as of October 31, 2011. The OS ranged from 234 to 512 days, with a median survival of 397 days and a one-year survival rate of 66.7%. In the 12-week-interval chest CT assessment, three patients showed stable disease (SD), and the other three showed progressive disease (PD). The PFS of patients ranged from 88 to 512 days, the median PFS being 96 days. Longer OS and PFS were correlated with SD. Although not directly comparable, the OS and the PFS of this study were greater than those of the docetaxel or the best supportive care group in other studies.

Conclusion:

HAP may prolong the OS and the PFS of inoperable stage IIIb/IV NSCLC patients without significant adverse effects. In the future, more controlled clinical trials with larger samples from multi-centers should be conducted to evaluate the efficacy and the safety of HAP.

Keywords: HangAm-Plus(HAP), non-small-cell lung cancer, progression-free survival, overall survival, cancer treatments, antitumor

1. Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death in economically developed countries and the second leading cause of death in developing countries [1]. The burden of cancer is growing in developing countries as a result of aging populations and increasing cancer-associated lifestyle factors including stress, smoking, physical inactivity, and westernized diets. Lung cancer has been the most common type of cancer in the world for several decades. In the year 2008, there were estimated 1.61 million new cases of lung cancer, representing 12.7% of all new cancers. It was also the most common cause of death from cancer, with 1.38 million deaths (18.2% of total cancer-related deaths) [2]. Generally, the prognosis for lung cancer is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of only 15% [3]. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of all cases of lung cancer [4] and consists of three major cell types; adenocarcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and largecell carcinomas [5]. The treatment for NSCLC involves surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy [6] and is determined by disease stage. Surgery is the mainstay treatment for early-stage and localized disease, and multimodal therapy is the norm for regionallyadvanced disease. For late-stage IIIb or IV NSCLC patients, palliative chemotherapy is the most commonly performed conventional treatment [7]. HangAm-Plus(HAP) has been used to treat solid tumors such as lung, pancreatic, colorectal, and stomach cancers at the East West Cancer Center (EWCC), Dunsan Oriental Hospital (Daejeon, Korea) since its development in 1996 [8 - 13]. Several research findings support its therapeutic role in the immune protective function, antiangiogenesis, inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and metastasis prevention [8 - 13]. Significant prevention of basic fibroblastgrowth- factor (bFGFs)-induced human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVE) cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and capillary -like tubular network formation due to the use of HAP has been reported [14]. HAP has also demonstrated a significant concentration- dependent inhibition of cell motility and invasiveness of NCI-H460 NSCLC cells. The tight junctions (TJs) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were the critical targets of HAPinduced anti-invasive activity [15]. Yoo et al. reported a successful 7-year follow-up case of a squamous-cell lung carcinoma recurrence treated with HAP [16].

Jeong et al. carried out a prospective study on inoperable NSCLC patients treated with HAP and proved its synergistic effect with conventional therapy and prolonged survival rate [17]. The goal of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of HAP as a third-line treatment for advanced-stage IIIb/IV NSCLC.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

In this observational study, six NSCLC patients were followed from April 2010 to October 2011 while being treated at the EWCC. The treatment plan was explained in detail, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study gained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dunsan Oriental Hospital of Daejeon University on May 24, 2010 (IRB number: DJDSOH-10-01). Patients eligible for this study included:

(1) Patients with cytologically- or histologically-verified NSCLC stage IIIB or IV who were not candidates for treatment with a curative intent;

(2) Stage IIIb/IV NSCLC patients who refused first-line chemotherapy or failed at least one cycle of chemotherapy;

(3) Patient with a measurable malignant lesion based on the international standard of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [ 18], complete/partial response (CR/PR), progression/stable disease (PD/SD);

(4) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) [ 19] score ≤ 2;

(5) Patients with expected survival of at least three months;

(6) Completion of anticancer drugs and/or radiation treatment three weeks prior to participation;

(7) Recovery from all adverse effects of anticancer drugs and/ or radiation treatment;

(8) Proper bone marrow function (peripheral absolute granulocyte count 〉150×109 /L; platelet count 〉100×109 /L);

(9) Proper liver function (bilirubin ≤ 1.5 mg/dL; serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase or serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase〈 3×normal) and kidney function (creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dL).

2.2. Baseline

Demographic and clinical data (age, gender, histological or cytological tumor type, performance status, disease stage, body height and weight), as well as laboratory measures (hemoglobin, leukocyte and platelet counts, sodium, potassium, calcium, albumin, spartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase and creatinine), were recorded.

2.3. Treatment

HAP is an anti-cancer herbal formula consisting of eight different herbs (Table 1). The manufacture of the HAP and the quality control of the herbs in the formula were managed by Kim’s Pharmaceutical Company in Daejeon, Korea. HAP is prepared in a capsule form with a dried powder of the extracted herbs inside. HAP is generally taken three times a day (TID), 1,000 or 2,000 mg at a time, after meals (3,000 or 6,000 mg/day). Patients were treated with HAP only, without any concurrent conventional treatments.

Table. 1. Ingredients of HangAm-Plus.

| Herbs (Latin Botanical Name ) | Relative amount (mg) |

|---|---|

| Panax noto-ginseng (Burk.) f.H. Chen | 84.0 |

| Cordyceps militaris (Berk.) Sacc. | 64.0 |

| Tulipa edulis Bak. | 64.0 |

| Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | 64.0 |

| Bos taurus domesticus Gmelin | 64.0 |

| Pinctada martensii Dunker | 64.0 |

| Boswellia carterii Birdw. | 48.0 |

| Commiphora molmol Engl. | 48.0 |

| Total amount (per capsule) | 500.0 |

2.4. Assessment of disease progression

Tumor response rate was measured using computed tomography (CT) scans. CT scans were taken at the time of initial administration and after 12 weeks of treatment. Tumor size was recorded following the RECIST guidelines [18]. Compared with the initial tumor size, disappearance of all target lesions was confirmed as CR, at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions was confirmed as PR, at least a 20% increase in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions was confirmed as PD, and neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD was confirmed as SD.

2.5. Endpoints

Endpoints included the following:

(1) Survival rate, including overall survival (from initial administration of HAP to death or to last follow-up) and progression-free survival (from randomization to the first of either recurrence or relapse, second cancer, or death) [ 20],

(2) Response rate, measured by using the International standard provided by RECIST as CR, PR, PD, and SD [ 18],

(3) Adverse effects during HAP treatment, reported based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0 [ 21].

2.6. Statistical analysis

Correlations between the "tumor response", "treatment period" and "survival time" were investigated using Fisher's exact tests. Estimates of the median OS and the median PFS were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analyses based on all six patients. Estimates for each "SD-PD" and "before-after" group were calculated using the same method. The comparisons of group survival functions were conducted using log rank tests based on the OS and the PFS.

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ characteristics

The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. Subjects in the study consisted of two males (33.3%) and four females (66.7%). All six patients were histologically diagnosed as having an adenocarcinoma-type NSCLC. One patient had stage IIIb (16.7%) and 5 patients had stage IV (83.3%) NSCLC. Their mean age was 61 years. During the course of treatment, two patients were treated for less than 100 days (33.3%), and four patients were treated for more than 100 days (66.7%). The median duration of HAP treatment was 5.3 months. In the 12-week-interval chest CT assessment, three patients showed SD, and the other three patients showed PD (Table 2 and 3).

Table. 2. Patients Characteristics.

| Gender | Male | 2 (33.3%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 4 (66.7%) | |

| Age | Median | 61 (47~74) |

| Type | Adenocarcinoma | 6 (100%) |

| Stage | IIIb | 1 (16.7%) |

| IV | 5 (83.3%) | |

| ECOG* | 1 | 1 (16.7%) |

| 2 | 5 (83.3%) | |

| Prior Therapy | Yes | 5 (83.3%) |

| No | 1 (16.7%) | |

| Treatment Duration (Day) | ˂100 | 2 (33.3%) |

| ≥100 | 4 (66.7%) |

*ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Table. 3. Patients Summaries.

| No. | Age | Sex | Stage | ECOG | Treatment Period | RECIST | PFS days | OS days | Remarks (Oct.31 2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 52 | M | IIIb | 2 | 90 | SD | 210 | 398 | Expired |

| 2 | 74 | M | IV | 2 | 81 | SD | 512 | 512 | Alive |

| 3 | 74 | F | IV | 2 | 407 | PD | 88 | 497 | Alive |

| 4 | 47 | F | IV | 1 | 170 | SD | 497 | 497 | Alive |

| 5 | 68 | F | IV | 2 | 111 | PD | 94 | 276 | Expired |

| 6 | 51 | F | IV | 2 | 103 | PD | 97 | 234 | Expired |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (0 = fully active; 1 = restricted in physically strenuous activity; 2 = up and about more than 50% of waking hours; 3 = limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours; 4 = totally confined to bed or chair; 5 = dead); RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors: Complete response (CR) = disappearance of all target lesions. Any pathological lymph nodes must have reduction in short axis to〈 10mm. Partial response (PR) = at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions, taking as a reference the baseline sum diameters. Progressive disease (PD) = at least a 20% increase in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions, taking as a reference the smallest sum under study (this includes the baseline sum if that is the smallest under study). In addition to the relative increase of 20%, the sum must also demonstrate an absolute increase of at least 5 mm. Stable disease (SD) = neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD, taking as a reference the smallest sum of the diameters under study; PFS = progression free survival; OS = overall survival.

3.2. Overall survival

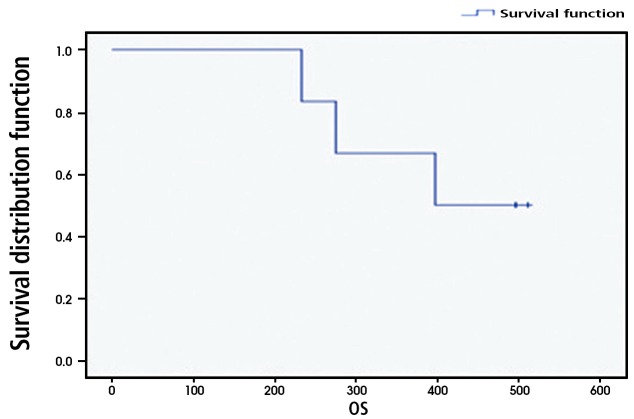

Of the six patients, three patients expired during the study, and the remaining three patients were still living as of October 31, 2011. The OS ranged from 234 to 512 days, with a median survival of 397 days and a 66.7% one-year survival rate. Two of the three SD patients and one of the three PD patients survived (Fig. 1). Patients with SD showed longer overall survival than patients with PD. One of the two patients who received less than 100 days of HAP treatment survived, and two of the four patients who received more than 100 days of HAP treatment survived. No significant OS variation correlated with the administration period.

Fig. 1. Overall survival. Patients’ overall survival ranged from 234 to 512 days, with a median survival of 397 days and a 66.7% one-year survival rate (standard error = 19.2).

3.3. Progression-free survival

PFS is defined as the time from randomization to the first of either recurrence or relapse, second cancer, or death [22]. The PFS of the patients ranged from 88 to 512 days, with a median PFS of 96 days. SD patients showed a longer PFS than patients with progressive disease. One of the two patients who received less than 100 days of HAP treatment had progressive disease. Three of the four patients who received more than 100 days of HAP treatment had progressive disease. No significant PFS variation correlated with the administration period.

3.4. Safety

No HAP-related hematologic/non-hematologic toxicity, hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity were observed. However, transient abdominal discomfort was reported in two patients (Patients no. 1 and 5) during treatment, but no treatment was required and symptoms disappeared soon after. No patient discontinued treatment due to any HAP-related adverse events.

3.5. Cases of long survival

Patient No. 2 was a 74-year-old male patient diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC (T4N3M1a) in September 2009. He received three cycles of chemotherapy (paclitaxel-cisplatin) from September 2009 to November 2009. He failed his first-line chemotherapy and experienced significant adverse effects. Due to his old age and adverse effects, he discontinued conventional treatment and received HAP, instead as a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatment, from May 7, 2010, to August 26, 2010. HAP, 6,000 mg, was administered daily. His performance status was ECOG 2 at the time of initial administration. According to the chest CT scans taken on May 31, 2010, and September 1, 2010, his disease was stable, and the cancer growth has been halted for at least 12 weeks (3 months) since the initial HAP administration. As of October 31, 2011, he was still alive without any evidence of progression. Patient No.3 was a 74-year-old female patient diagnosed on May 2010 with stage IV NSCLC with spinal metastasis in T11. As she refused all conventional therapy and wished to be treated with CAM only, she received HAP from June 16, 2010 to August 2, 2011. HAP, 6,000 mg, was given daily. Her performance status was ECOG 2 at the time of initial administration. Follow-up chest CT scans were taken on June 16, 2010, and September 17, 2010, and showed SD but aggravation of the spine (T11) metastasis was revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on September 29, 2010. She was then treated for the spine metastasis by using radiation therapy from November 16, 2010, to November 22, 2010. As of October 31, 2011, she was still alive without any evidence of progression. Patient No. 4 was a 47-year-old female patient diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC on August 31, 2009. She received her first-line of chemotherapy (gemzar-cisplatin) from September 2009 to November 2010 and her second-line of chemotherapy (tarceva) from November, 2009 to February, 2010. She received HAP as the third-line treatment from April 6, 2010, to December 8, 2010. HAP, 6,000 mg, was administered daily. Her performance status was ECOG 1 at the time of initial administration. Chest CT scans taken on June 16, 2010, and September 15, 2010, showed SD, and cancer growth has been halted for at least 12 weeks (3 months) since the initial HAP administration. As of October 31, 2011, she was still alive without any evidence of progression.

4. Discussion and conclusion

In advanced cancer trials, the time-honored standard for demonstrating efficacy of new adjuvant therapies is an improvement in the OS [23]. However, the OS requires extended followups, which may prevent the timely dissemination of results and a consequent delay in the implementation of an effective treatment regimen, so the PFS is sometimes suggested as an alternative endpoint to the OS [24]. The weakness of the PFS lies in its overlooking the long-term effects of the treatment, such as endorgan toxicities or secondary malignancies, that may adversely impact survival [25]. In this study, both the OS and the PFS were used as endpoints to measure the efficacy of HAP to make up for the short follow-up time and the small population of the study. Chemotherapy is the primary first-line treatment for 70 to 80% of patients who present with locally advanced (stage IIIb) or metastatic (stage IV) disease. In advanced NSCLC, the objectives of chemotherapy are prolonged survival, improved quality of life and enhanced symptom control [22]. Although first-line chemotherapy has contributed to the survival of patients with advanced NSCLC, the overall and the one-year survival rates (8- 11 months and 27-47%, respectively) still remain poor [26 - 27]. In stage IIIb/IV patients, response to first-line therapy is generally short lived, and progression is often witnessed on an average of 4-6 months after discontinuation of the treatment. For patients who fail to respond to first-line chemotherapy, second-line chemotherapy is recommended. A recent study indicated that 50% of all patients receive second-line treatment. Docetaxel or pemetrexed is used as a second-line chemo agent for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC patients who have progressed on first-line therapy [28]. In a current review, objective response rate of second-line chemotherapeutic agents was found to be lower than that of the first-line setting in advanced NSCLC cases [29]. Considering the incurable nature of advanced NSCLC and the modest survival seen in second-line settings, patient convenience and preference must be taken into account when selecting the third-line treatment agent [30]. The impact of second-line chemotherapy has been studied in a large cohort of 4,318 patients in 19 phase III trials. Docetaxel (75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) significantly prolonged median survival, one-year survival and median PFS in comarison with best supportive care (median survival: 7.5 versus 4.6 months; median PFS: 2.1 versus 1.6 months; one year survival: 37 versus 12%) [24]. In our study, median survival was 13.2 months (397 days), median PFS was 3.2 months (96 days) and the one-year survival rate was 66.7%. The results of this study showed that HAP treatment yielded an OS and PFS longer than three of the best supportive care group and the docetaxel-treated group with no significant adverse events. The limitations of this observational study include (1) the small numbers of patients, (2) the short and variable HAP treatment period, (3) the different treatment histories of the individual patients and (4) limitations on regular and continuous followups. In conclusion, HAP is worth investigating as a third-line regimen for stage IIIb/IV NSCLC patients who fail chemotherapy, but its effect has not yet been confirmed. In the future, additional controlled clinical trials with larger samples from multi-centers are warranted to further evaluate the efficacy and the safety of HAP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine grant (#K10061).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramalingam S, Belani C. Systemic chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: recent advances and future directions. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl 1):5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Care. [[cited 2012 January 20]];Types of lung cancer. Available from: http://www.lungcancer.org/reading/types.sphp .

- 6.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(1):10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govindan R. The Washington manual of oncology. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho JH, Yoo HS, Lee YW, Son CK, Cho CK. Clinical study in 320 cases for cancer patients on the effect Hangamdan. Collect Dissert Daejeon University. 2004;12(2):157–175. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi BL, Son CK. The clinical study in 62 cases for lung cancer patients on the effects by Hangamdan. Collect Dissert Daejeon University. 2001;10(1):121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo HS, Choi WJ, Cho JH, Lee YY, Seo SH, Lee YW et al. The clinical study in 105 cases for stomach cancer patients on the effects by Hangamdan. Hyehwa Med. 2000;9(2):7–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee YY, Seo SH, Yoo HS, Choi WJ, Cho JH, Lee YW et al. The clinical study in 83 cases for colorectal cancer patients on the effects by Hangamdan. J of Kor Oriental Oncology. 2000;6(1):165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han SS, Cho CK, Lee YW, Yoo HS. A case report on extranodal marginal zone B cells of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type lymphoma treated with HangAmDan. Korean J Orient Int Med. 2008;29(3):810–818. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bang SH, Lee JH, Cho JH, Lee YW, Son CG, Cho CK et al. A case report of pancreatic cancer treated with lymph node metastasis. Korean J Orient Int Med. 2007;28(4):978–985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bang JY, Kim EY, Shim TK, Yoo HS, Lee YW, Kim YS et al. Analysis of anti-angiogenic mechanism of HangAmDan-B (HAD-B), a Korean traditional medicine, using antibody microarray chip. BioChip J. 2010;4(4):350–355. doi: 10.1007/s13206-010-4412-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi YJ, Shin DY, Lee YW, Cho CK, Kim GY, Kim WJ et al. Inhibition of cell motility and invasion by HangAmDan-B in NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;26(6):1601–1608. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo SH, Yoo HS, Cho CK, Lee YW. A case report for recurred squamous cell lung carcinoma treated with Hang-Am-Dan: 7-year follow up. Korean J Orient Int Med. 2007;28(2):385–390. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong TY, Park BK, Lee YW, Cho CK, Yoo HS. Prospective analysis on survival outcomes of nonsmall cell lung cancer stages over IIIb treated with HangAm-Dan. Chinese Journal of Lung Cancer. 2010;13(11):1009–1015. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2010.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill S, Sargent D. Endpoints for adjuvant therapy trials: has the time come to accept disease-free survival as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival? Oncologist. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):624–629. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. [[cited 2012 January 20]];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov .

- 22.Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, Sause W, Smith TJ, Baker S, Jr et al. American society of clinical oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(2):330–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driscoll JJ, Rixe O. Overall survival: still the gold standard: why overall survival remains the definitive end point in cancer clinical trials. Cancer J. 2009;15(5):401–405. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181bdc2e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandrekar SJ, Qi YW, Hillman SL, Allen Ziegler, KL, Reuter NF, Rowland KM, Jr et al. Endpoints in phase II trials for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c0a313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Socinski MA. The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of unresectable stage III and IV nonsmall cell lung cancer. Respir Care Clin N Am. 2003;9(2):207–236. doi: 10.1016/S1078-5337(02)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noble J, Ellis PM, Mackay JA, Evans WK. Second-line or subsequent systemic therapy for recurrent or progressive non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and practice guideline. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1(9):1042–1058. doi: 10.1097/01243894-200611000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotta K, Fujiwara Y, Kiura K, Takigawa N, Tabata M, Ueoka H et al. Relationship between response and survival in more than 50,000 patients with advanced non-smallcell lung cancer treated with systemic chemotherapy in 143 phase III trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(5):402–407. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000268673.95119.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stinchcombe TE, Socinski MA. Considerations for secondline therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl1):28–36. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]