Introduction

Segmental atrophy of the liver has been recently related to a rare and under-recognized pseudotumor [1]. The typical features of segmental atrophy include loss of hepatic parenchyma, mild inflammation, bile ductular proliferation, biliary retention cysts, and early fibrotic and elastotic changes. Segmental atrophy is often associated with remote vascular injury and may occasionally present as a sub-capsular mass lesion. Singhi et al. [1] reported on atrophic pseudotumor of the liver and identified multiple stages with different histologic findings. Early lesions are characterized by collapsed parenchyma, focal elastotic changes, and brisk bile ductular proliferation. The elastotic changes become more evident in the later stages, and in the final stage the lesion presents as an elastotic nodule with dense fibrosis.

Although the morphological appearance of segmental atrophy of the liver has been described, very few cases have been reported. In addition, because the clinicopathological characteristics of this pseudotumor remain poorly described, clinicians are frequently unaware and ill prepared to deal with this clinical entity.

Case Series

Over the last 3 years, three patients have been diagnosed and treated with segmental atrophy at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The first case was a 73-year-old male who was noted to have an unusual whitish discolored “mass” along the entire edge of the left lateral segment of liver during laparoscopy. The patient was undergoing a laparoscopic revision of his gastric conduit, which had narrowed at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus following a prior esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. The “mass” lesion in the liver was resected, and final pathological specimen showed a benign reactive lesion. Features were consistent with segmental atrophy including loss of hepatic parenchyma, mild inflammation, mild ductular proliferation, biliary retention cysts, and early fibrotic and elastotic changes (Fig. 1).

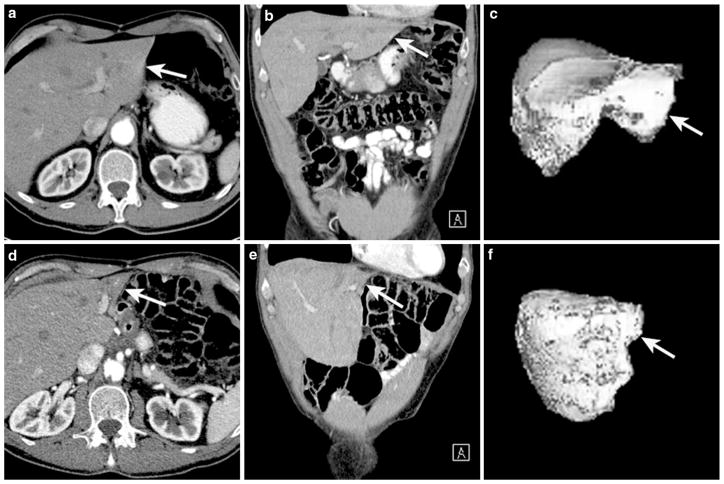

Fig. 1.

73-year-old male with history of esophageal cancer. Axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images of the liver following intravenous contrast administration show normal left lobe (arrow). 3D image of the liver in shaded surface display (c) shows a normal liver and normal left lobe. Total liver volume is 1,606 cc, and volume for segments II and III is 239 cc. Following distal esophagectomy and gastric pull-up CT images in the axial (d) and coronal (e), views show significant reduction in volume of the left lobe (arrow). 3D image of the liver in shaded surface display (f) shows a reduction in liver volume (now 1,435 cc), particularly segments II and III (now 56 cc)

The second patient was a 74 years old male with a suspected cholangiocarcinoma that had been diagnosed at an outside hospital. Per report, cross-sectional imaging revealed a “mass” in the left hemi-liver and some associated lobar atrophy. Without a tissue diagnosis, the patient was started on gemcitabine-cisplatin chemotherapy. Upon presenting to Johns Hopkins, an MRI revealed atrophy of the left liver and a possible primary “mass” in the left hemi-liver (Fig. 2). The patient initially underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy, which revealed several white plaques on the left liver and firmness in the left liver. An open left hemi-hepatectomy was performed, and the final pathology eventually showed no evidence of malignancy. Instead, final pathology noted a liver that was atrophic with markedly inflamed large intrahepatic bile ducts and rare clusters of reactive epithelium consistent with segmental atrophy.

Fig. 2.

74-year-old male with cholangiocarcinoma involving the left lobe of the liver. Axial (a) and coronal (b) MR images of the liver following intravenous contrast administration show dilated intraheptic ducts involving the left lobe (arrow). 3D volume rendered image of the liver (c) shows a normal liver and normal left lobe. Total liver volume is 1,973 cc, and volume for segments II, III, and IV is 331 cc. Repeated MR in 4 weeks show continued atrophy of the left lobe, as shown in the axial (d) and coronal (e) planes. 3D volume rendered image of the liver (f) shows a reduction in liver volume (now 1,610 cc), particularly segments II, III, and IV (now 88 cc)

The third patient was a 73-year-old male who had a questionable liver lesion in the setting of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy, followed by a conversion to an open approach due to the presence of dense adhesions in the area of the left liver. The hard tissue between the left lateral liver and the gastro-hepatic ligament was biopsied and revealed extensive inflammatory tissue with no obvious adenocarcinoma. A “wedge” resection of the “mass” was then performed, and the final pathological specimen showed dense chronic inflammation infiltrate with scarring and bile duct proliferation.

While three patients were treated at Johns Hopkins with a segmental lobar atrophy pseudotumor, another eight pathology “indeterminate mass” specimens were referred to Johns Hopkins from outside institutions: three wedge resections, one right hemi-liver, one left hemi-liver, and three wedge biopsies. An experienced hepatobiliary pathologist (RA) reviewed each case and found each to have features consistent with segmental atrophy. Each specimen was graded according to amount of residual liver parenchyma, grade of inflammation, elastotic changes and extent of elastosis, vascular injury, bile ductular proliferation and biliary retention cysts [1]. One case was reported as an early lesion, characterized by collapsed hepatic parenchyma, occasional island of residual hepatocytes, and brisk bile ductular proliferation. Two cases were defined as nodular elastosis (the third stage of segmental atrophy of the liver), characterized by rare islands of hepatocytes in an elastotic matrix and portal tracts. One case was defined as nodular fibrosis (the fourth stage of segmental atrophy of the liver), characterized by nodules with dense fibrosis, small biliary retention cysts, vascular changes, and residual portal tracts (Fig. 3). The other four cases were described as lobar atrophy, without any further specification. Abnormal blood vessels were a common finding in the context of lobar atrophy. Remote vascular injury interested both arteries and veins and was characterized by abnormally thick-walled vessels, thrombosis, fibrosis, and recanalization. Bile duct proliferation was also a common finding. In addition, in one case, the ductular proliferation was associated with biliary retention cysts. The background liver was cirrhotic in one patient.

Fig. 3.

Gross image: a Three slices of the lesion presented as liver pseudotumor. b This 3.5 × 8.0 cm tumor located under the liver capsule blue (arrows) has ill-defined boarders and a variegated white tan cut surface. The slightly prominent round structures (arrow head) will prove histologically to be thrombosed and fibrotic vessels. Bar = 1.0 cm

Discussion

Segmental atrophy of the liver can result in the development of a rare pseudotumor, with a distinctive histologic presentation. The rarity of this pseudotumor and the difficult differential diagnosis can lead to erroneous management of patients with segmental atrophy. Singhi et al. [1] recently delineated the clinicopathological spectrum of this pseudotumor to better define its pathological features. Singhi et al. [1] described stepwise pathological changes that characterize different pathological stages of lobar atrophy; the progressive pathological features range from parenchymal collapse with occasional islet of hepatocytes and ductular proliferation, to nodular elastosis, to the final stage with nodules and dense fibrosis. Cases from the present series confirm the clinicopathologic peculiarity of this rare pseudotumor and demonstrate the range of findings that the hepatopathologists must be familiar with to diagnose this under-recognized pseudotumor.

Lobar or segmental atrophy of the liver have been considered as a complication of different benign and malignant disease of the liver and of the bile ducts, and defined as complete or partial, based on the extension and histological appearance [2–4]. Complete atrophy can manifest itself as a firm and pink region of liver (lobar or segmental), which is markedly shrunken and well demarcated from the background liver. The absence of hepatocytes and the presence of fibrosis, inflammatory infiltrate, and the proliferation of bile ducts are distinctive. Partial atrophy is the reduction in size ≥50 % of a lobe or a hepatic segment, with similar histological appearance. Most often atrophy is related to a specific underlying disease process: hydatid disease, cholangiocarcinoma, alcoholic cirrhosis, chronic active hepatitis with cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, cryptogenic cirrhosis, pyogenic cholangitis, sclerosing cholangitis, and acute hepatic failure [5]. While much more uncommon, the clinical situation of isolated “benign” segmental atrophy can occur as demonstrated in the current case series and is often associated with remote vascular injury.

The presence of elastotic changes is the typical feature of the pseudotumor, as previously determined by Singhi et al. [1]. The elastic fibers that form the elastic tissue are in turn made of elastin associated with microfibrils [6]. The main component of microfibrils is a glycoprotein called fibrillin, which is coded by the genes fibrillin-1 and fibrillin-2 [7]. The presence of fibrillin-1 was demonstrated in both normal and pathologic adult liver [8]. In normal adult, liver fibrillin-1 is present in the perisinusoidal space and in portal tracts. In cirrhotic adult, liver fibrillin-1 is observed in septa around cirrhotic nodules and in the perisinusoidal space [6]. The presence of elastotic fiber has been also shown to be more prevalent in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [2]. Elastic fibers are typically found widely around central venules and between portal tracts and perivenular areas. As described by Singhi et al. [1] and confirmed by our findings, the presence of elastic fibers in pseudotumor seems to be more focal and dense.

In conclusion, the current series highlights the rare clinical entity of lobar atrophy associated with pseudotumor. Lobar atrophy can have multiple stages ranging form parenchymal collapse to nodular elastosis, to nodular fibrosis, to formation of a more discrete pseudotumor. While surgeons should always presume that lobar atrophy may be associated with an underlying malignant etiology, surgeons and hepatopathologists should similarly be aware of segmental atrophy of the liver as an uncommon and often unrecognized hepatic pseudotumor.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Contributor Information

Gaya Spolverato, John L. Cameron Professor of Alimentary Surgery, Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Blalock 688, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA.

Robert Anders, Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Ihab Kamel, Department of Radiology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Timothy M. Pawlik, Email: tpawlik1@jhmi.edu, John L. Cameron Professor of Alimentary Surgery, Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Blalock 688, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA

References

- 1.Singhi AD, Maklouf HR, Mehrotra AK, et al. Segmental atrophy of the liver: a distinctive pseudotumor of the liver with variable histologic appearances. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:364–371. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820b0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakayama H, Itoh H, Kunita S, et al. Presence of perivenular elastic fibers in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis Fibrosis Stage III. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:407–409. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufour JF, DeLellis R, Kaplan MM. Reversibility of hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:981–985. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ham JM. Lobar and segmental atrophy of the liver. World J Surg. 1990;14:457–462. doi: 10.1007/BF01658667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamireau T, Dubuisson L, Lepreux S, et al. Abnormal hepatic expression of fibrillin-1 in children with cholestasis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:637–646. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez F, Pereira L. The fibrillins. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 1999;31:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubuisson L, Lepreux S, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Expression and cellular localization of fibrillin-1 in normal and pathological human liver. J Hepatol. 2001;34:514–522. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]