Abstract

Although the significance of focally enhanced gastritis (FEG) as a marker of Crohn’s disease (CD) has been contested in adults, several studies suggest that it may be more specific of CD in pediatric patients. This study describes the detailed histological features of FEG in pediatric IBD and clarifies its association with CD. A series of 119 consecutive newly diagnosed IBD patients (62 CD, 57 UC) with upper and lower gastrointestinal biopsies were evaluated. The histology of the gastric biopsies was reviewed blinded to final diagnoses and compared to age-matched healthy controls (n=66). FEG was present in 43% of IBD patients (CD 55% vs. UC 30%, p=0.0092) and in 5% of controls. Among CD patients, FEG was more common in younger patients (73% in age ≤10, 43% in age >10, p=0.0358) with peak in the 5–10 year old age group (80%). The total number of glands involved in each FEG foci was higher in UC (6.4±5.1 glands) than in CD (4.0±3.0 glands, p=0.0409). Amongst the CD cohort, patients with FEG were more likely than those without FEG to have active ileitis (79% vs. 40%, p=0.0128) and granulomas elsewhere in gastrointestinal tract (82% vs. 43%, p=0.0016). There was no correlation between FEG and other gastrointestinal findings of UC. We demonstrate that differences in FEG seen in pediatric CD and UC relate to not only their frequencies but also the morphology and relationship with other gastrointestinal lesions. Furthermore, FEG is associated with disease activity and the presence of granulomas in pediatric CD.

Keywords: focally enhanced gastritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

The appropriate classification of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease as either Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) is important, because of their differences in natural history, treatment, and prognosis. However, establishing a definitive diagnosis can be challenging due to the overlapping features between these two disorders and the possibility of CD-like features in cases of naïve UC, such as discontinuous disease, rectal sparing, and ileal inflammation, particularly in pediatric patients.(1–6) In many cases, the key histologic differentiation of CD and UC is largely limited to the identification of granuloma regardless of the segment of involvement. Consequently, in the pediatric setting esophagogastroduodenoscopy is routinely performed during the initial evaluation for IBD, as up to 20% of children with CD have granulomas limited to the upper gastrointestinal tract.(7–9)

Focally enhanced gastritis (FEG) is an inflammatory lesion often found in CD that involves discrete inflammatory foci containing lymphocytes, histiocytes, and granulocytes. FEG has been suggested as a specific marker of CD, detected with a prevalence ranging from 43 to 76%.(10–13) However, the specificity of FEG for CD has been challenged as several studies have demonstrated that FEG is found in 12–24% of UC patients and 2–19% of non-IBD patients.(10, 13–15) In addition, a study reported a lower prevalence of 10.5% of FEG in adult-onset CD patients with a positive predictive value of only 5.9%.(16)

Nevertheless, FEG has been touted as more specific for IBD in the pediatric population. Sharif et al. demonstrated that FEG was present in 65% of CD and 21% of UC, but only 2% of non-IBD pediatric patients, and similar findings were confirmed by two recent studies.(14, 15, 17) Altogether, the predictive value of FEG during an evaluation for IBD is unclear and a thorough histologic description of FEG seen in children with IBD is lacking.

The goals of this study were to further determine the diagnostic significance of FEG in pediatric patients and to better characterize the histologic features of FEG. First, a retrospective histologic review of gastric biopsies from pediatric patients who presented with new onset IBD was performed to establish the prevalence of FEG. Second, the clinico-pathological characteristics of FEG were examined with particular attention to differences between CD and UC. Finally, a detailed review of concurrent esophageal, duodenal, ileal, and colonic biopsies was performed to assess for correlations between the presence of FEG and other mucosal gastrointestinal lesions.

Materials and Methods

Selection of Patient Cohort

Consecutive patients with IBD who received care in the pediatric gastroenterology clinic of MassGeneral Hospital for Children between March 2010 and March 2012 were identified by electronic medical record review. The original biopsies from those with a confirmed final diagnosis of CD and UC who underwent both upper and lower endoscopic evaluation (with biopsy) at the time of their IBD diagnosis (and were naive to treatment) were reviewed. The ultimate diagnosis and classification of IBD was established based on the correlation of endoscopic, pathologic, and imaging findings, as well as the clinical course. Patients who were diagnosed at another institution or who did not have upper endoscopy prior to the establishment of the diagnosis (and initiation of therapy) were excluded. Patients were accrued into age groups (based on their age at time of initial endoscopic evaluation) defined a priori: 0–5 years of age, 6–10 years of age, 11–15 years of age, 16–17 years of age, and 18–20 years of age. The endoscopy report was examined for macroscopic gastric lesions (i.e. gastric erythema, aphthoid lesions). In addition, the location and extent of the lower gastrointestinal disease was classified according to the Paris classification.(18) The average duration of follow-up for IBD patients was 3.5±2.4 years. The control group was age-matched to the study group. This group was composed of randomly selected patients who underwent upper endoscopic examination with biopsy without significant gross findings during the same period (March 2010-March 2012). This control group consisted of patients with non-specific upper gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. epigastric pain, bloating, nausea) without lower gastrointestinal symptoms (n=43) and those with both upper gastrointestinal symptoms and mild lower gastrointestinal symptoms who had a concomitant colonoscopy without pathologic findings. Controls were followed for an average of 8.5±0.7 months following endoscopy without development of further symptoms. For both IBD and control groups, the institutional standard pediatric biopsy protocol was applied, i.e., to take 2 biopsies per site using a standard adult size biopsy forceps.

This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Histologic assessment

All serial sections of each biopsy specimen were examined by one gastrointestinal pathologist (T.U.) who was blinded to the patient’s clinical condition and the final diagnosis. Eight to ten H&E stained serial sections typically were available for each case. Additional deeper sections were often available for review in cases with equivocal findings, such as the presence of possible granuloma or FEG.

Gastric biopsies

Each gastric biopsy was evaluated for the presence of FEG. FEG was defined as the presence of one or more foci of pit or glandular inflammation with a relatively normal background mucosa.(12) All cases with focal inflammatory lesions were re-reviewed by two pathologists (T.U. and G.Y.L.) together at a multi-headed microscope to render a consensus diagnosis. For each gastric biopsy, the number of foci of FEG, the total number of glands or foveolae involved by FEG, and the type of inflammatory cells composing the FEG focus (e.g., lymphocytes, plasmacytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, or histiocytes) was recorded. Finally, the presence of a granulomatous reaction, defined as aggregations of epithelioid granuloma or multinucleated giant cells (sometimes observed adjacent to foci of FEG,) was also assessed.

A diagnosis of “granulomatous gastritis” was applied for cases showing epithelioid granulomas with or without multinucleated giant cells unrelated to inflamed pit/gland. Helicobacter pylori infection was excluded on the basis of morphology. In addition, negative immunostaining for Helicobacter pylori or thiazine stain was 73% of biopsies with any type of gastritis.

Extragastric gastrointestinal biopsies

Histologic features of concurrent esophageal, duodenal, ileal, and colorectal biopsies were also evaluated and analyzed in association with FEG. The recorded diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of gastrointestinal (extra-gastric) biopsies

| Organ/Diagnosis | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Esophagus | |

| Lymphocytic esophagitis | high numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes (>50 or more/HPF) with no or rare granulocytes |

| Granulomatous esophagitis | any type of inflammation associated with granulomas |

| Reflux esophagitis | intraepithelial eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration with basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of papillae, and spongiosis |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | severe intraepithelial eosinophilic infiltrate with more than 20 eosinophils per high-power field, |

| Candidal esophagitis | presence of Candida ± neutrophilic infiltration. |

| Duodenum and ileum | |

| Granulomatous duodenitis/ileitis | granulomatous inflammation unrelated to crypt rupture |

| Active duodenitis/ileitis | granulocytic inflammation with epithelial damage.* |

| Chronic inactive duodenitis/ileitis | increase of chronic inflammation with mild villous blunting without active inflammation |

| Peptic injury | active duodenitis with gastric foveolar metaplasia |

| Colorectum | |

| Chronic colitis | quiescent, or mild, or moderate, or severe colitis |

| Granulomatous colitis | chronic colitis associated with isolated epithelioid granuloma**. |

Peptic injury with foveolar metaplasia was excluded.

Crypt-associated granulomas due to mucin leakage were excluded from this category.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s T-test, and categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test (Excel Statistics, SSRI, Tokyo, Japan). Differences were considered to be significant if the two-tailed p-value was <0.05.

Results

Study Group

A total of 119 consecutive patients were accrued into the a priori-defined age groups [0–5 years of age (7 CD, 4 UC); 6–10 years of age (15 CD, 11 UC); 11–15 years of age (15 CD, 13 UC); 16–17 years of age (13 CD, 15 UC); 18–20 years of age (12 CD, 14 UC)]. Additional demographic information on the cohort is available in Table 2. All patients had at least one biopsy specimen taken from the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and colorectum. Terminal ileal biopsies were available for 45 (73%) patients with CD and 46 (81%) patients with UC.

Table 2.

Demographics of the patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

| Parameters | Crohn’s disease (n=62) | Ulcerative Colitis (n=57) |

|---|---|---|

| Male % | 54.80% (n=34) | 52.60% (n=30) |

| Age (years) | 12.2 | 13.3 |

| Disease Location (Paris Classification*) | L1 (distal 1/3 ileum +/− limited cecal disease): 21.0% (n=13) | E1 (ulcerative proctitis): 10.5% (n=6) |

| L2 (colonic): 22.6% (n=14) | E2 (left-sided, distal to splenic flexure): 12.3% (n=7) | |

| L3 (ileocolonic): 56.5% (n=35) | E3 (extensive, hepatic flexure distally): 15.8% (n=9) | |

| E4 (pancolitis, proximal to hepatic flexure): 61.4% (n=35) |

Ref.18

Prevalence of FEG in IBD patients and controls

FEG was detected in 43% of the IBD patients (51/119) and in 5% of control children (3/66) (p<0.0001). FEG was also more frequently observed in patients with CD (55%, 34/62) than those with UC (30%, 17/57, p=0.0092) and controls (5%, 3/66, p<0.0001).

Among the patients with CD, the prevalence of FEG was higher in the younger age groups (73% at age ≤10, 43% at age >10, p=0.0358), with peak in the 6–10 year age group (80%). There was no significant relationship between the frequency of FEG and the age of the patients with UC or the control group.

Endoscopic Appearance and FEG

Macroscopic disease was seen in 36.1% (43/119) of the overall IBD group, including 13.4% (16/119) with aphthoid lesions. Gastric lesions were seen in 31.6% (18/57) of UC patients and 40.3% (25/62) of CD patients. Macroscopic gastric findings (aphthoid lesions, erythema) were more commonly seen in IBD patients with FEG than in the absence of FEG (49.0% vs. 26.5%, p=0.011). Aphthoid lesions were also more common in IBD patients with FEG than those without FEG (21.6% vs. 7.4%, p=0.024).

Disease Location and FEG

The frequency of FEG among the various groups according to the Paris classification showed no difference between the prevalence of FEG in any subgroup either for UC patients [E1, 33.3% (2/6); E2, 28.6% (2/7); E3, 22.2% (2/9); and E4 31.4% (11/35)]or CD patients [L1, 61.5% (8/13); L2, 50.0% (7/14); and L3, 54.3% (19/35)].

Histologic Pattern of FEG in CD and UC

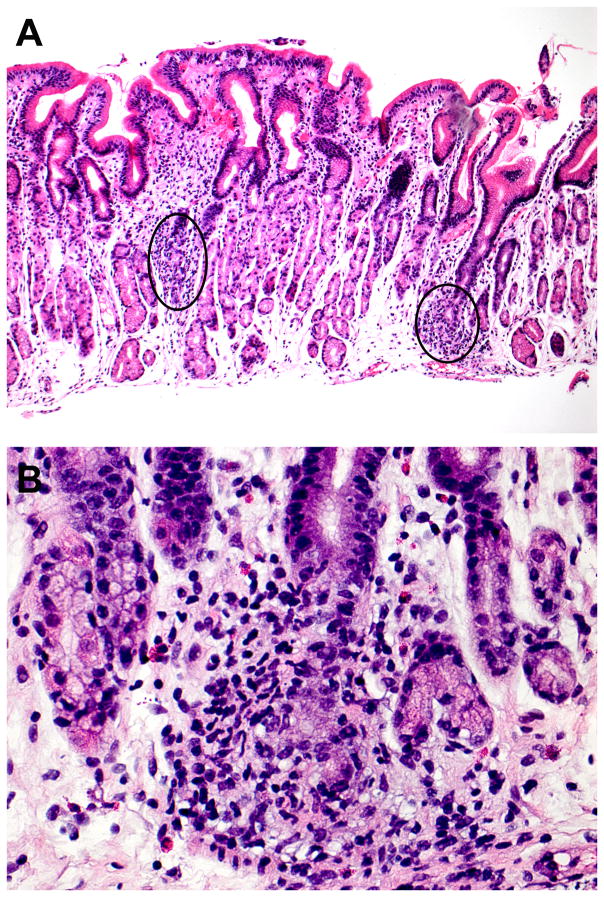

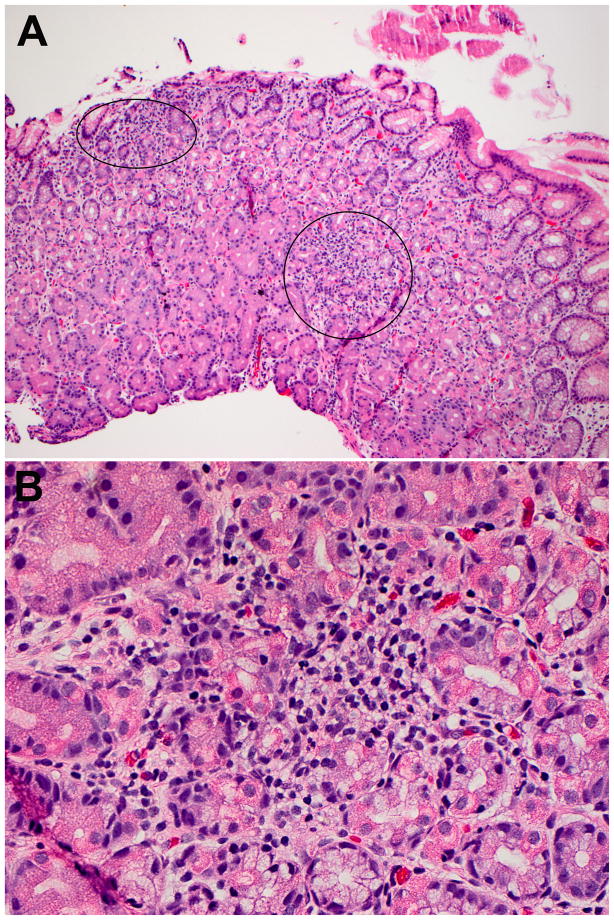

The number of FEG foci ranged from one to five (mean: 2.2) in each biopsy specimen (Figure 1, 2). Each FEG lesion involved from one to 12 pits/glands, and mostly up to 3 pits/glands (87%). These characteristics did not differ between CD and UC patients. However, the total number of glands involved as part of a focus of FEG was higher in patients with UC (6.4±5.1) compared to those with CD (4.0±3.0, p=0.0409). The characteristic features of FEG in patients with CD and UC are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Focally enhanced gastritis in a pediatric patient with Crohn’s disease. This biopsy contains two foci of FEG (A). The foci of FEG involve two glands (left focus) and a single gland (right focus: B), respectively.

Figure 2.

Focally enhanced gastritis in a pediatric patient with ulcerative colitis. This biopsy contains two foci of FEG (A). The foci of FEG involve three glands (upper left focus) and at least six glands (right focus: B), respectively.

Table 3.

Histologic patterns of FEG in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

| Findings of FEG | Crohn’s disease n=34 | Ulcerative colitis n=17 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of involvement | |||

| Number of FEG foci in a biopsy (mean±S.D.) | 2.0±1.5 | 2.5±1.4 | 0.2607 |

| Number of pits/glands involved in a FEG (mean±S.D.) | 2.0±1.3 | 2.5±2.4 | 0.1687 |

| Total Number of glands involved in a biopsy (mean±S.D.) | 4.0±3.0 | 6.4±5.1 | 0.0409 |

| Type of cells involving FEG focus | |||

| Lymphohistiocytes only | 13 (38%) | 7 (41%) | 1.0000 |

| Presence of granulocytes | 9 (26%) | 8 (47%) | 0.2084 |

| Presence of ill formed histiocytic aggregates | 14 (41%) | 3 (18%) | 0.1221 |

FEG, focally enhanced gastritis; S.D., standard deviation.

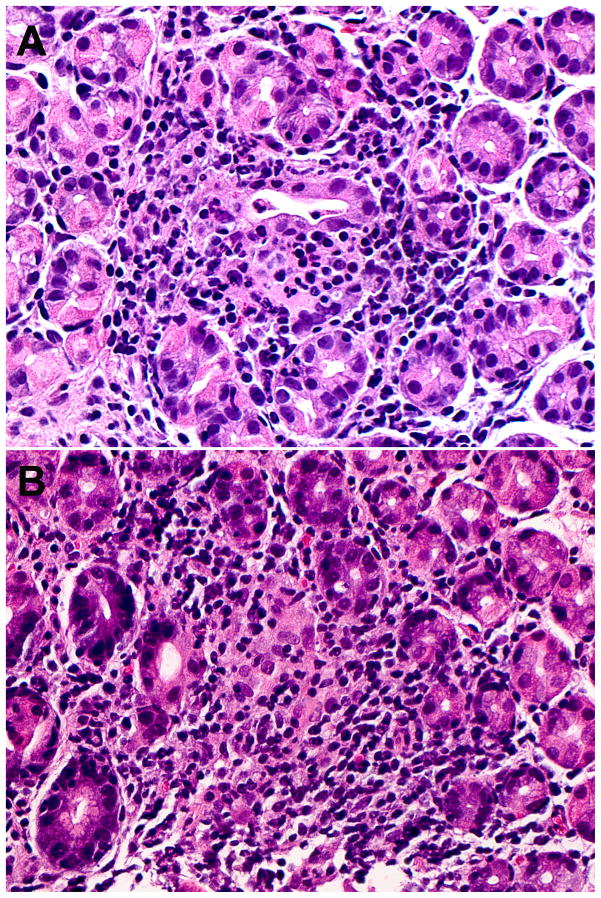

All FEG lesions contained lymphohistiocytic infiltrates. In addition, 33% of FEG lesions had varying degrees of granulocytes (neutrophils in 26% and eosinophils in 12% of the cases), and 33% were accompanied by a granulomatous reaction (Figure 3). Granulocytic infiltrates were less frequently observed in FEG lesions from CD patients (26%) compared to those found in UC patients (47%), while ill-formed histiocytic aggregates reactions were more frequently present adjacent to FEG in CD (41%) than in UC patients (18%), however these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). Granulomatous reaction adjacent to FEG focus was usually composed of a small aggregate of epithelioid histiocytes, or even included multinucleated giant cells. However, prominent, middle sized epithelioid granulomas were also observed in two cases.

Figure 3.

Focally enhanced gastritis with granulocytic infiltration (A) and ill formed histiocytic aggregates (B).

Characteristics of gastrointestinal biopsies and their association with FEG

Table 4 shows a summary of the diagnoses encountered in all biopsies.

Table 4.

Summary of entire gastrointestinal findings in biopsies from patients with CD, UC, and Control.

| Findings | CD n=62 |

UC n=57 |

Control n=66 |

P-value

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD vs UC | CD vs Control | UC vs Control | ||||

| Esophagus | ||||||

| Granulomatous esophagitis | 7 (11%) | 0 | 0 | 0.0135 | 0.0052 | 1.0000 |

| Lymphocytic esophagitis | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0.6199 | 0.1108 | 0.4634 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 5 (8%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (8%) | 0.4419 | 1.0000 | 0.4486 |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 0.6064 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Candidal esophagitis | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0.4790 | 1.0000 | 0.4634 |

|

| ||||||

| Stomach | ||||||

| Focally enhanced gastritis | 34 (55%) | 17 (30%) | 3 (5%) | 0.0092 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Granulomatous gastritis | 9 (15%) | 0 | 0 | 0.0030 | 0.0011 | 1.0000 |

| H.pylori gastritis | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0.6064 | 1.0000 | 0.5960 |

| Chronic active gastritis (H.pylori-) | 6 (10%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0.2757 | 0.0564 | 0.5960 |

| Chronic inactive gastritis (H.pylori-) | 5 (8%) | 7 (12%) | 2 (3%) | 0.5479 | 0.2628 | 0.0798 |

| Ulcer | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0.4790 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

|

| ||||||

| Duodenum | ||||||

| Granulomatous duodenitis | 4 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0.1200 | 0.0523 | 1.0000 |

| Active duodenitis | 5 (8%) | 12 (21%) | 1 (2%) | 0.0649 | 0.1068 | 0.0006 |

| Chronic inactive duodenitis | 0 | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 0.4790 | 0.4966 | 1.0000 |

| Peptic injury | 4 (6%) | 3 (5%) | 0 | 1.0000 | 0.0523 | 0.0967 |

|

| ||||||

| Terminal ileum | (n=45) | (n=46) | ||||

| Granulomatous ileitis | 10 (22%) | 0 | - | 0.0005 | - | - |

| Active ileitis | 26 (58%) | 5 (11%) | - | <0.0001 | - | - |

| Chronic inactive ileitis | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | - | 1.0000 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Colorectum | ||||||

| Normal/chronic quiescent colitis | 16 (26%) | 2 (4%) | - | 0.0007 | - | - |

| Granulomatous colitis | 36 (58%) | 0 | <0.0001 | - | - | |

| Active colitis | 46 (74%) | 55 (96%) | 0.0006 | |||

CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

The detection of esophagitis was higher in patients with CD than UC (26% vs. 11% p=0.0360) and those of the control group (26% vs. 11%, p=0.0370). Granulomatous esophagitis was exclusively found in CD patients (11%). There was no significant difference among the three groups of patients with regard to the other esophageal findings.

In the stomach, the presence of gastritis (all variants combined) was more common in patients with CD (73%) than UC (44%, p=0.0017) and to control children (9%, p<0.0001). Granulomatous gastritis was present in 15% patients with CD. However, the prevalence of the other subtypes (chronic active gastritis and chronic inactive gastritis) did not differ among the three groups.

Duodenitis was more frequent in the CD group (23%) and UC group (28%) than in the control group (5%, p=0.0034 and 0.0003, respectively). Granulomatous duodenitis was present in 6% patients with CD. Chronic active duodenitis with foveolar metaplasia (consistent with peptic injury) was similarly observed in patients with CD (6%) and UC (5%).

The frequency of active ileitis was significantly higher in patients with CD (58%) than those with UC (11%, p<0.0001). Active ileitis in UC patients was always patchy and mild compared to the ileitis seen in 42% of CD patients. Ileitis in the CD cohort was moderate to severe and was often accompanied by erosion or ulceration. Granulomatous ileitis was detected in 22% of CD patients. In colonic biopsies, active inflammation was observed in at least one biopsy in 96% of the UC patients and 74% of those with CD (p=0.0007). Granulomatous colitis was present in 58% patients with CD.

Correlation of FEG with active inflammation elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract

Lymphocytic esophagitis was included in this analysis because it has been suggested as a manifestation of pediatric CD.(19, 20) Lymphocytic esophagitis, active duodenitis, and active ileitis were more frequently observed in CD patients with FEG compared to those without, although the former two did not reach significance. There also was no difference between the presence of FEG and the presence of active colitis. The results are presented in Table 5. In UC patients, there was no correlation between the presence of FEG and other mucosal findings, including the activity of colitis.

Table 5.

Correlation of FEG with other gastrointestinal findings in patients with Crohn’s disease.

| Findings | FEG

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n=34) | Absent (n=28) | ||

| Presence of active inflammation* | |||

| Lymphocytic esophagitis | 8 (24%) | 2 (7%) | 0.0972 |

| Active duodenitis | 6 (18%) | 3 (11%) | 0.4945 |

| Active ileitis | 19 (79%) | 8 (40%) | 0.0128 |

| Active colitis | 26 (76%) | 20 (71%) | 0.7728 |

| Presence of granuloma** | |||

| Upper gut (esophagus/stomach/duodenum) | 14 (41%) | 3 (11%) | 0.0099 |

| Lower gut (ileum/colon) | 26 (76%) | 11 (39%) | 0.0043 |

| Entire gut | 28 (82%) | 12 (43%) | 0.0016 |

Cases with granulomatous inflammation was also included if active inflammation was present.

Granuloma associated with crypt-rupture was excluded from this category.

Correlation of FEG with the presence of granulomas in CD

Epithelioid granulomas were more frequently observed in CD patients with FEG than in those without FEG, in both upper and lower gastrointestinal biopsies (Table 5). Granulomas in CD patients with and without FEG were present in esophageal (18% vs. 4%, p=0.1160), gastric (24% vs. 4%, p=0.0332), duodenal (9% vs. 4%, p=0.6199), terminal ileal (36% vs. 10%, p=0.0445), and colonic (74% vs. 36%, p=0.0044) biopsies. Overall, 82% CD patients with FEG had at least one granuloma detected in their gastrointestinal biopsies, while the frequency was only 43% in those without FEG (p=0.0016).

Correlation of FEG with the presence of lower gastrointestinal symptoms

Given the concern for overlooking a diagnosis of IBD in patients with FEG, the frequency of two common lower gastrointestinal symptoms, rectal bleeding and diarrhea, was assessed in the IBD cohort. Rectal bleeding and diarrhea was present in 90.2% (46/51) of IBD patients with FEG compared to 91.2% (62/68, p=0.86) of patients with IBD without FEG.

Discussion

The recognition of FEG as a gastric manifestation of IBD was first reported in 1997 by Oberhuber et al.(12). The prevalence of FEG in pediatric IBD patients is 54–69% in CD and 16–24% in UC, while it is present in 2–7% of non-IBD pediatric patients.(14, 15, 17, 21) Furthermore, several studies have indicated a particularly high prognostic value in pediatric patients as 61–76% of children with FEG are ultimately diagnosed with IBD.(17) However, although FEG is particularly common in children with CD, the presence of FEG does not reliably distinguish CD and UC in isolation.(17) Our study is the first to examine a cohort of children with newly-diagnosed IBD for the occurrence of FEG.

This study is the first to comprehensively define the histologic differences in FEG between CD and UC patients. We demonstrated that compared to what is seen in UC patients, FEG in CD involved a lesser number of pits/glands in each gastric biopsy. Although a granulomatous reaction observed in association with FEG could be a manifestation of CD, it is not always easily distinguishable from a mucin type granuloma developing secondary to ruptured crypt, as described in the colon.(22–24) However, in practice, these subtle morphologic differences of FEG cannot always reliably differentiate between CD and UC.

We also show that FEG in our pediatric CD population was commonly associated with the presence of granuloma elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, as well as with active inflammation. Indeed, 82% of CD patients with FEG had granulomas in either upper or lower gastrointestinal biopsies, which were observed in only 43% of those without FEG. Perhaps more intriguing is that the detection of microscopically-active ileitis was significantly more frequent in CD patients with FEG (79%) compared to those without FEG (40%, p=0.0128), indicating that FEG may be a marker of disease activity along with the presence of granuloma in pediatric CD. In contrast, no significant correlation was noted between the presence of FEG and any clinico-pathological parameters in UC patients. This observation suggests that FEG in UC patients, in contrast to those with CD, is likely not directly related to the activity of the disease, although the significance of upper gastrointestinal lesion of UC remains unknown.(15, 25)

Clearly, children with IBD have a much higher prevalence of FEG than non-IBD subjects.(14, 15) The identification of FEG in a pediatric patient with gastrointestinal symptoms raises the possible diagnosis of IBD, and thus, it is interesting that a large retrospective study found no differences in the prevalence of FEG between the disease location of newly diagnosed IBD (by Paris classification) and advocated for thorough evaluation for CD with the detection of FEG.(21). Similarly, we also observed no association with macroscopic disease location. However, our study did find a strong association between FEG and both ileal histologic activity and the presence of granulomas.

The absence of lower gastrointestinal biopsies from our control group could be construed as a limitation of our study. However, while significant majority of patients with FEG and IBD had lower gastrointestinal symptoms (rectal bleeding or diarrhea) those were absent in the control group. Furthermore, the associated histologic activity detected in the duodenum and esophagus of IBD patients was not noted in the control group and finally, at the time of patient selection, none of the patients of the control group had been retroactively diagnosed with IBD (with an average follow-up of 8.5 months).

In summary, we confirmed that although FEG is more typical of CD, it is also seen in a substantial number of children with UC. We also demonstrated that there are differences between FEG observed in CD and UC not only with regard to morphology but also the relationship to other mucosal abnormalities. Notably, FEG may be an indicator of disease activity and a marker for the presence of granulomas in pediatric CD. Thus, the detection of FEG in a pediatric patient with gastrointestinal symptoms but lacking any further evidence for histologic or endoscopic inflammation is unlikely to signal underlying CD.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

References

- 1.Glickman JN, Bousvaros A, Farraye FA, et al. Pediatric patients with untreated ulcerative colitis may present initially with unusual morphologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:190–197. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odze R. Diagnostic problems and advances in inflammatory bowel disease. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:347–358. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000064746.82024.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz J, Kahn E, Grancher K, et al. Atypical rectosigmoid histology in children with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:2034–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho RS, Abadom V, Dilworth HP, et al. Indeterminate colitis: a significant subgroup of pediatric IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:258–262. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000215093.62245.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geboes K, Colombel JF, Greenstein A, et al. Indeterminate colitis: a review of the concept--what’s in a name? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:850–857. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odze RD. Pathology of indeterminate colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S36–40. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000127686.69276.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellaneta SP, Afzal NA, Greenberg M, et al. Diagnostic role of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:257–261. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200409000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundhal PS, Stormon MO, Zachos M, et al. Gastral antral biopsy in the differentiation of pediatric colitides. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:557–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemberg DA, Clarkson CM, Bohane TD, et al. Role of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the initial assessment of children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meining A, Bayerdorffer E, Bastlein E, et al. Focal inflammatory infiltrations in gastric biopsy specimens are suggestive of Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease Study Group, Germany. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:813–818. doi: 10.3109/00365529708996539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberhuber G, Hirsch M, Stolte M. High incidence of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in Crohn’s disease. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:49–52. doi: 10.1007/s004280050133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberhuber G, Puspok A, Oesterreicher C, et al. Focally enhanced gastritis: a frequent type of gastritis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:698–706. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parente F, Cucino C, Bollani S, et al. Focal gastric inflammatory infiltrates in inflammatory bowel diseases: prevalence, immunohistochemical characteristics, and diagnostic role. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:705–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hummel TZ, ten Kate FJ, Reitsma JB, et al. Additional value of upper GI tract endoscopy in the diagnostic assessment of childhood IBD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:753–757. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318243e3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharif F, McDermott M, Dillon M, et al. Focally enhanced gastritis in children with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1415–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xin W, Greenson JK. The clinical significance of focally enhanced gastritis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1347–1351. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138182.97366.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHugh JB, Gopal P, Greenson JK. The Clinical Significance of Focally Enhanced Gastritis in Children. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;32:295–299. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826b2a94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Pediatric modification of the Montreal classification for inflammatory bowel disease: the Paris classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1314–1321. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebach DR, Vanderheyden AD, Ellison JM, et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: a possible manifestation of pediatric upper gastrointestinal Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:45–49. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubio CA, Sjodahl K, Lagergren J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: a histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roka K, Roma E, Stefanaki K, et al. The value of focally enhanced gastritis in the diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.11.003. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee FD, Maguire C, Obeidat W, et al. Importance of cryptolytic lesions and pericryptal granulomas in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:148–152. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahadeva U, Martin JP, Patel NK, et al. Granulomatous ulcerative colitis: a re-appraisal of the mucosal granuloma in the distinction of Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 2002;41:50–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shepherd NA. Granulomas in the diagnosis of intestinal Crohn’s disease: a myth exploded? Histopathology. 2002;41:166–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin J, McKenna BJ, Appelman HD. Morphologic findings in upper gastrointestinal biopsies of patients with ulcerative colitis: a controlled study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1672–1677. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f3de93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]