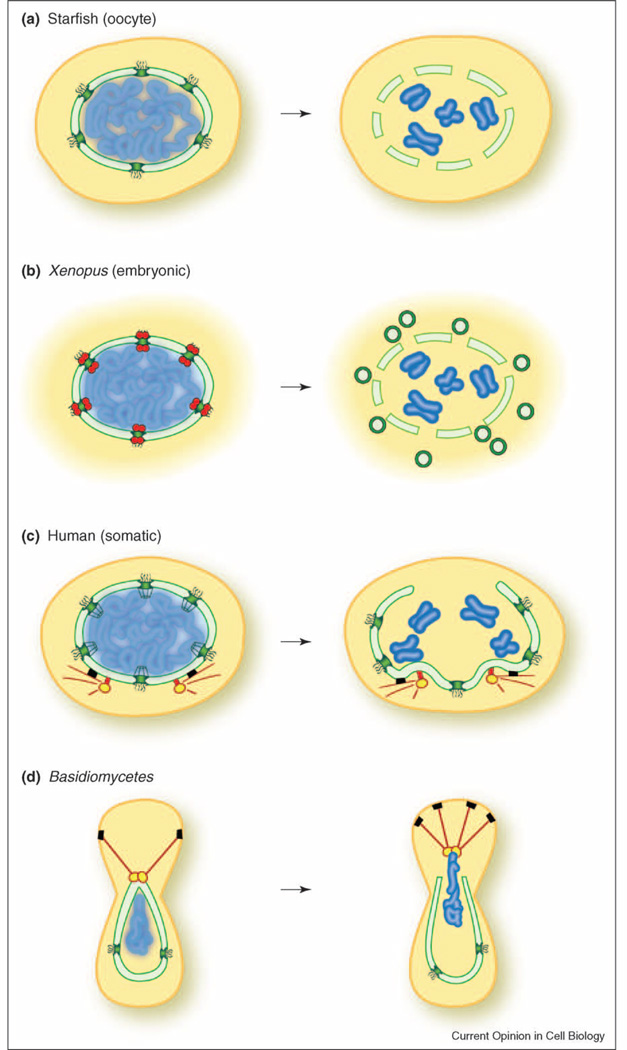

Figure 3.

Mechanistic models of nuclear envelope (NE) disassembly. Key findings in various experimental systems are schematically depicted. Cells are not drawn to scale; it is notable that the oocyte is very large compared to a somatic cell, since size may impose specific constraints on the mechanics of NE breakdown. (a) In starfish oocytes, early alterations in permeability at the nuclear pore (green) have been observed, and correlate with an early phase of nuclear pore complex (NPC) disassembly. During the second phase of disassembly, larger holes in the NE are proposed to emanate from the site of disassembled pores. (b) In embryonic-like nuclei formed in vitro from Xenopus egg extract, nuclear pore proteins recruit the COPI complex (red) to the NE. Local concentration of this coatomer complex may then lead to vesiculation of the NE, as depicted, or to a non-conventional role for COPI. (c) In human tissue culture cells (somatic), microtubules originating from the centrosomes (yellow) connect to the NE via the microtubule motor dynein (black). Dynein-mediated movement is thought to then pull the NE toward the centrosomes, eventually causing a rupture at a distal region of the NE. (d) In Ustilago maydis, a basidiomycete, the NE is dragged from the mother cell to the bud by microtubules and dynein (black). There is an early increase in permeability, suggestive of pore remodeling, and then an obvious opening in the NE near the spindle pole body (yellow). Subsequently, the chromosomes enter the daughter cell where the spindle is formed, and the remnant of the NE collapses into the mother cell.