Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was developed to evaluate the incidence of off-label prescribing at a pediatric rehabilitation center. Secondary objectives were to describe the medications, patient age groups, and diagnoses most often associated with off-label prescribing.

METHODS: This was a prospective observational study conducted at an academic, inpatient children's rehabilitation center from November 11, 2011, to April 1, 2012. Patients younger than 16 years of age who received at least 1 prescription medication were included. Data were collected from the patients' electronic medical records.

RESULTS: A total of 240 medications orders were placed during the study, with 57% written off-label. Thirty-five patients (88%) received at least 1 off-label medication. Forty-nine percent of the orders were for patients younger than the approved range, with 48% written for an unapproved indication, 2% for an alternative route of administration, and 1% for an unapproved age and indication. Children 2 to 12 years of age received 40% of the off-label orders, followed by adolescents with 37%. The therapeutic classes most often prescribed off-label were central nervous system agents and anti-infectives.

CONCLUSION: Off-label prescribing was found in the majority of children receiving rehabilitative services, a rate as high or higher than that reported in pediatric acute care or clinic settings. The medications prescribed off-label most often were central nervous system agents, reflecting the need to study medications in the chronic rehabilitation population to optimize function in children with brain or spinal cord injury.

INDEX TERMS: child, off-label, prescribing, rehabilitative services

INTRODUCTION

The pediatric population is underrepresented in studies of medication safety and efficacy. It is now widely recognized that developmental changes in infants and children affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of many drugs, producing a need for age-dependent dose adjustments.1,2 Information obtained in adults cannot be readily extrapolated to younger patients. Likewise, safety data from adult studies may not adequately represent the adverse effects seen in children or their frequency. While pediatric studies are necessary to address these issues, there are a number of difficulties inherent in conducting research in this patient population, including ethical considerations, smaller numbers of available patients, and age-appropriate formulations.3 Over the past decade, government incentives have stimulated interest in pediatric research, resulting in a significant increase in the number of drugs with pediatric prescribing information. Yet even with these advances, more than 75% of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs lack dosing, efficiency, and safety data pertaining to pediatrics.5 As a result, physicians must often resort to off-label prescribing, guided by clinical judgment and when available, information from case reports and postmarketing clinical trials. Off-label prescribing in children is a problem worldwide, as many countries face the same difficulties in establishing safety and efficacy of medications in children. It is estimated worldwide that 25% to 89% of hospitalized children and 69% to 100% of all patients in neonatal intensive care units receive at least 1 off-label medication.6–,13 The percentage of children receiving off-label prescriptions in the United States and British primary care settings is similar, 42% to 68%, with the highest rates reported in subspecialty clinics.14,15

Children requiring rehabilitative services for congenital or acquired medical conditions are a unique population that has not been evaluated for off-label prescribing. Although the number of children needing rehabilitative services is smaller than in the adult population, there is a growing need for these services.16 The Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities currently accredits 66 pediatric specialty rehabilitation programs in the United States, as well as 383 general rehabilitation programs that provide services to children and adolescents (written communication, Karen L. Vellenga). This study was developed to evaluate the incidence of off-label prescribing at a pediatric rehabilitation center and to describe the medications, patient age groups, and diagnoses most often associated with off-label prescribing. The findings from this study may be useful in identifying medications most in need of support for additional research in children receiving rehabilitative services.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective observational study was conducted in children who were admitted to a 19-bed inpatient unit at the Kluge Children's Rehabilitation Center between November 11, 2011, and April 1, 2012. Patients were excluded if they were 16 years of age or greater or if they did not receive a prescription medication during their stay. The institution's Investigational Review Board for Health Sciences Research approved the study. Demographic data collected from the patients' electronic medical records included age, gender, weight, and admitting diagnosis. Patients were grouped according to FDA age classifications: neonates (0 days to 1 month), infants (1 month to 2 years), child (2 years to 12 years), and adolescent (12 years to 16 years).17 The indication for use was identified for all medications ordered, based on diagnoses and the prescribers' daily progress notes. We defined off-label prescribing as any medication order written outside of the FDA labeled indication or age range.

The primary endpoint of the study was the frequency of off-label prescribing, reported as both the percentage of total medication orders written off-label during the evaluation period and the percentage of patients evaluated who received at least 1 medication outside the FDA-approved indications or age range. Secondary endpoints were identification of patient age groups, diagnoses, and therapeutic classes most often associated with off-label prescribing. Descriptive statistics were used to assess patient demographics and indices related to the frequency of off-label prescribing.

RESULTS

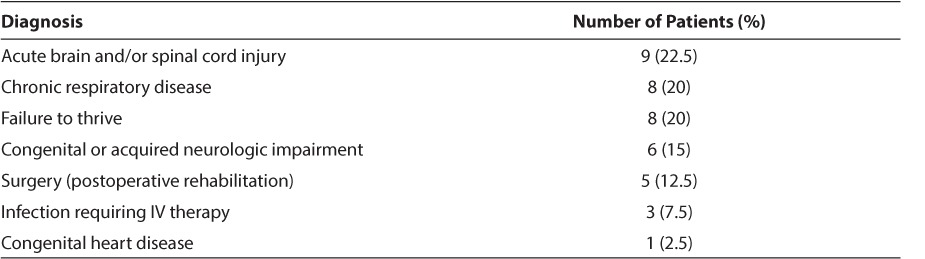

A total of 57 patients were screened, 40 of which were included. Of the patients who were excluded, 14 did not meet age criteria, 2 did not receive any prescription medications, and 1 was admitted for services unrelated to rehabilitation. Nineteen patients (48%) were male, and the median age was 5 years, with a range of 3 weeks to 15 years. The largest age group was children 2 to 12 years of age, accounting for 35% of the study patients, followed by infants (33%), adolescents (27%), and neonates (5%). Reasons for admission are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

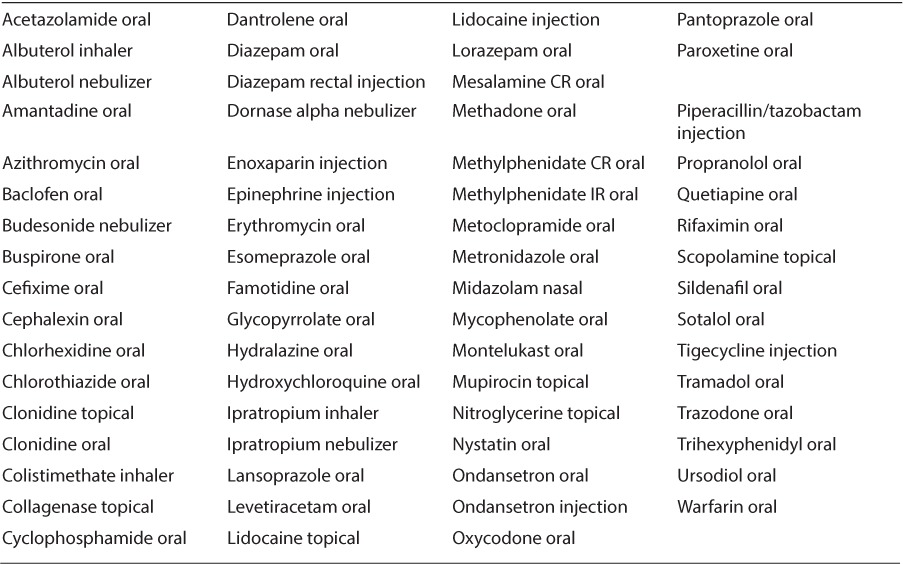

Admitting Diagnosis

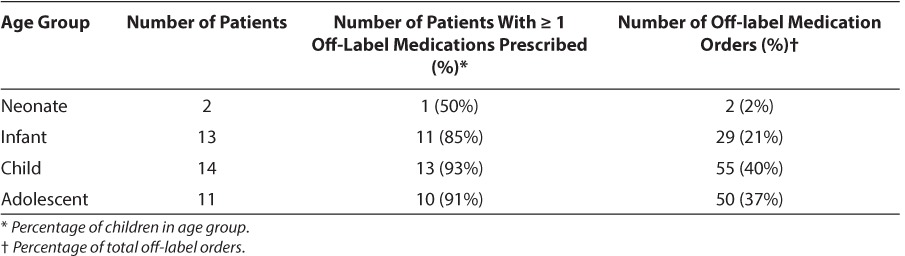

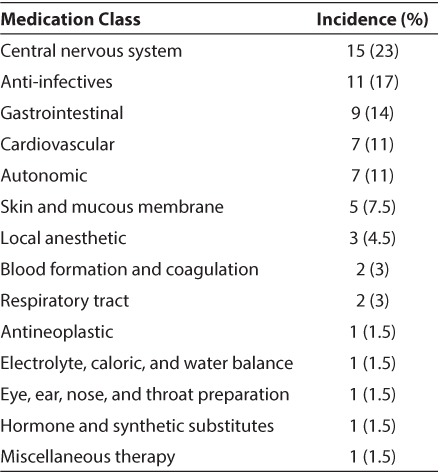

A total of 240 medications orders were placed during the study, with 136 (57%) written off-label. The median number of medications ordered per patient was 5, with a range of 1 to 16 medications (mean and SD, 6.5 ± 4.4). Thirty-five patients (88%) received at least 1 off-label medication. The number of off-label medications ordered per patient ranged from 1 to 13 (median 4, mean 3.9 ± 2.6). The percentage of patients receiving at least 1 off-label medication was similar between males and females (43% and 57%, respectively). Sixty-seven of the 136 off-label medication orders (49%) were for a patient younger than the approved age range (Table 2), 65 (48%) were for an unapproved indication, 3 (2%) were for an alternative route of administration, and 1 included use in both an unapproved age and indication. All medication doses were within the recommended dosing range.18 Sixty-six different drugs were prescribed off-label (Table 3). The 3 medications most often prescribed off label were famotidine (10%) as stress ulcer prophylaxis, levetiracetam (6%) to provide seizure prophylaxis following traumatic brain injury, and methadone (5%) to prevent iatrogenic opioid withdrawal. Off-label prescribing according to therapeutic class is listed in Table 4.

Table 2.

Off-label Prescribing by Patient Age Group

Table 3.

Off-Label Prescribing by Medication Name

Table 4.

Off-Label Prescribing by Medication Class

DISCUSSION

During the past 20 years, the United States has given significant consideration to the need for more information on the medications used in children. Congress has enacted several pieces of legislation to support pediatric research. In 1997, the FDA Modernization Act (FDAMA) introduced the first incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to conduct studies in infants and children, a patent extension allowing for 6 additional months of market exclusivity in return for submission of pediatric safety and efficacy data.19 The Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), enacted in 2003, strengthened the language in FDAMA by requiring that all new drug applications include a pediatric assessment. A waiver could be obtained for products not expected to be used in children. As a result of these programs, by November 2013 the FDA had granted exclusivity extensions to 198 drugs. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act of 2002 (BPCA) added provisions for funding studies of medications in pediatrics, including those off patent and not likely to be funded by manufacturers.20 This program, under the direction of the National Institute of Child Heath and Human Development, also publishes the Priority List of Needs in Pediatric Therapeutics, a compilation of those medications determined to be in greatest need of efficacy and safety data in children.

Several medications routinely used in children's rehabilitation centers have gained pediatric indications as a result of these legislative incentives.21 The FDA extended the approved age range for famotidine based on BPCA-funded studies, which provided pharmacokinetic data revealing a slower clearance in younger patients. Dosing and safety labeling for gabapentin was changed after pediatric studies demonstrated that children younger than 5 years of age required higher doses on a per-kilogram basis for seizure control than older children and new adverse events, including aggression and hostility, were reported in children younger than 12 years of age. The indication for levetiracetam was amended to include use as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial onset seizures in infants and children from 1 month to 4 years, expanding FDA approval for this drug to patients of all ages.

Despite successful examples such as these, it is evident that more work is needed to address the wide variety of medications being prescribed off-label. In this study, 88% of patients at a children's rehabilitation center received medications prescribed off-label. This reflects not only the use of medications in children younger than the age range approved by the FDA, but also the frequent use of medications for unapproved indications resulting from the extrapolation of treatment regimens used in adult rehabilitation centers. As anticipated, central nervous system (CNS) agents were prescribed off-label more often than any other therapeutic class, reflecting the prevalence of children with brain and spinal cord injury in this population. Medications for this population were needed to provide sedation and analgesia, to reduce spasticity, increase arousal and awareness, and relieve depression, anxiety, and agitation. As patients recovered, their medication needs shifted to improving cognitive function, with the addition of drugs such as methylphenidate, amantadine, and donepezil. Few CNS agents have pediatric approval, and earlier studies have documented high rates of off-label prescribing for children in other settings. In a study of children undergoing surgery, 73.4% of the sedatives and anesthetics used did not have a pediatric indication.22 Evaluation of antidepressant prescriptions from 85 managed care plans revealed that 90% of prescriptions for children 5 to 12 years of age and 73% of those for adolescents were written off-label.23

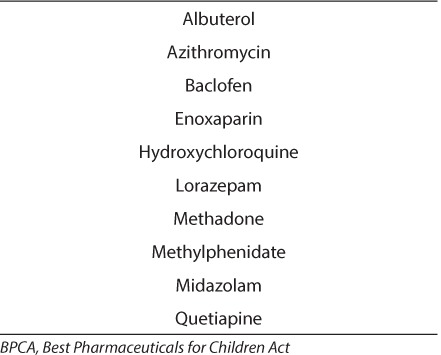

While many of the patients did receive prescriptions that were approved for pediatric use, including some with labeling resulting from BPCA funded research, the majority has not undergone thorough evaluation in children and many have not yet come to the attention of clinicians and agencies interested in supporting pediatric research. Of the 66 different off-label medications identified in the study, only 10 were on the 2011 BPCA Priority List (Table 5).19 Three more medications, montelukast, sildenafil, and trazodone, are currently being evaluated for BPCA listing and consideration for future prioritization. Medications that were identified for potential nomination to the BCPA Priority List from this study include clonidine for hypertension and autonomic instability after brain injury, levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis following brain injury, methadone for the prevention of iatrogenic opioid withdrawal, and oxycodone for pain management in children due to their lack of FDA approved indication.

Table 5.

Medications Used During the Study That Are on the 2011 BPCA Priority List21

Further analysis of the results from this study is limited by the small number of patients, which did not allow for assessment of the correlation between the frequency of off-label prescribing and therapeutic class, patient age, or diagnosis. Replication of this study using multiple centers or a longer data collection period may be useful in addressing these questions. In addition, the use of a single medication for multiple medical conditions, such as the use of lorazepam to provide sedation and treat spasticity, complicated data collection.

In conclusion, off-label prescribing was found in 88% of children receiving rehabilitative services in this sample, a rate as high as or higher than that reported in pediatric acute care or clinic settings. Reasons for the high rate of off-label prescribing included use in patients younger than the FDA-approved age range and use for unapproved indications. The majority of medications prescribed off-label were CNS agents, reflecting the need to optimize function in children with brain or spinal cord injury. The results of this study support the need for more research on medications for children undergoing rehabilitation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Presented, in part, at the Eastern States Residency Conference, Hershey, PA, May 2–4, 2012.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BPCA

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act

- CNS

central nervous system

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FDAMA

Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act

- PREA

Pediatric Research Equity Act

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GD. Developmental pharmacokinetics. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2010;17(4):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neville KA, Becker ML, Goldman JL, Kearns GL. Developmental pharmacogenomics. Pediatr Anesth. 2011;21(3):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemper EM, Merkus M, Wierenga PC et al. Towards evidence-based pharmacotherapy in children. Pediatr Anesth. 2011;21(3):183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuehn BM. Laws boost pediatric clinical trials, but report finds room for improvement. JAMA. 2012;307(16):1681–1682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SS, Hall M, Goodman DM et al. Off-label drug use in hospitalized children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):282–290. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimland E, Odlind V. Off-label drug use in pediatric patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(5):796–801. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimland E, Nydert P, Odlind V et al. Paediatric drug use with focus on off-label prescriptions at Swedish hospitals–a nationwide study. Acta Paediatrica. 2012;101(7):772–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khdour MR, Hallak HO, Alayasa KSA et al. Extent and nature of unlicensed and off-label medication use in hospitalised children in Palestine. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):650–655. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang CP, Veltri MA, Anton B et al. Food and Drug Administration approval for medications used in the pediatric intensive care unit: a continuing conundrum. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(5):e195–199. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe25b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phan H, Leder M, Fishley M et al. Off-label and unlicensed medication use and associated adverse drug events in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(6):424–430. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e057e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah SS, Hall M, Goodman DM et al. Off-label drug use in hospitalized children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):282–290. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eiland LS, Knight P. Evaluating the off-label use of medications in children. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006;63(11):1062–1065. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajcetic M, Jelisavcic M, Mitrovic J et al. Off label and unlicensed drugs used in paediatric cardiology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(10):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horen B, Montastruc J, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Adverse drug reactions and off-label drug use in paediatric outpatients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(6):665–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.t01-3-01689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazzano A, Mangione-Smith R, Schonlau M et al. Off-label prescribing to children in the United States outpatient setting. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ylvisaker M, Adelson D, Braga LW et al. Rehabilitation and ongoing support after pediatric TBI: twenty years of progress. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20(1):95–109. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric exclusivity study age groups. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApproval-Process/FormsSubmissionRequirements/ElectronicSubmissions/DataStandards-Manualmonographs/ucm071754.htm Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 18.Taketomo CK, Hodding JH, Kraus DM. Pediatric & Neonatal Dosage Handbook. 19th ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Food and Drug Administration. Drugs to which FDA has granted pediatric exclusivity for pediatric studies under Section 505A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/ucm050005.htm. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 20.National Institutes of Health. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) priority list of needs in pediatric therapeutics. 2011. http://bpca.nichd.nih.gov/about/index.cfm. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 21.Food and Drug Administration. New pediatric drug labeling information database. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/sda/sdNavigation.cfm?filter=&sortColumn=3a&sd=labelingdatabase&displayAll=false&page=4. Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 22.Smith MC, Williamson J, Yaster M et al. Off-label use of medications in children undergoing sedation and anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(5):1148–1154. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182501b04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czaja AS, Valuck R. Off-label antidepressant use in children and adolescents compared with young adults: extent and level of evidence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(9):997–1004. doi: 10.1002/pds.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]