Abstract

Insecurely attached people have relatively unhappy and unstable romantic relationships, but the quality of their relationships depends on how their partners regulate them. Some partners find ways to regulate the emotional and behavioral reactions of insecurely attached individuals, which promotes greater relationship satisfaction and security. We discuss attachment theory and interdependence dilemmas, and then explain how and why certain responses by partners assuage the cardinal concerns of insecure individuals in key interdependent situations. We then review recent studies illustrating how partners can successfully regulate the reactions of anxiously and avoidantly attached individuals, yielding more constructive interactions. We finish by considering how these regulation processes can create a more secure dyadic environment, which helps to improve relationships and attachment security across time.

Keywords: Attachment insecurity, interdependence dilemmas, dyadic regulation, conflict, support

Interdependence is a defining feature of close relationships in that people's goals, desires, and well-being are often dependent on the actions and continued investment of their romantic partners [1]. Situations that involve compromise, providing support, or making sacrifices for the partner or relationship make interdependence salient [2]. When partners’ goals and desires are at odds, they often need to change or set aside their own personal interests for what is best for their partner and/or relationship [3]. Doing so, however, makes individuals vulnerable to exploitation, rejection, or loss, especially if their partner is not sufficiently invested or responsive [3,4].

The way in which people respond to such “interdependence dilemmas” is partly governed by the outcomes they have experienced when dependent on others in past relationships [5,6,7]. Avoidantly attached individuals, for example, have experienced rejection and have learned that caregivers are not reliable, so they protect themselves by avoiding situations that might increase reliance on their partners [8]. In contrast, anxiously attached individuals desire greater closeness, but also fear abandonment and are hypersensitive to threats to their relationships, which interfere with the intimacy they crave [9].

A large body of research has examined the destructive ways in which avoidant and anxious (insecurely attached) individuals react to different types of interdependence dilemmas, particularly conflict and support situations [10,11]. However, relationship thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced not only by the types and degree of attachment insecurity of each partner, but also by the actual responses of each partner within the broader interdependence context of their relationship. These dyadic regulation processes have been the focus of a program of research indicating that attachment insecurity does not spell doom for insecure people or their relationships [12,13,14]. Instead, partners’ responses in certain interdependence dilemmas—and the secure dyadic environment they can create—can protect relationships from the damaging effects of insecurity and thus foster greater satisfaction and security.

Attachment Insecurity and Reactions to Interdependence Dilemmas

The attachment system evolved to keep individuals in close proximity to their primary caregivers, especially when individuals feel threatened, distressed, or challenged [5,15]. The attachment system is activated (turned on) when these events occur, such as when coping with interdependence dilemmas. This, in turn, triggers specific behavioral reactions designed to restore felt security [16]. How individuals have been treated (or perceive they have been treated) by prior caregivers determines how they view and react to the challenges of interdependence in adulthood [5,6]. A history of being able to rely on caregivers for responsive care and support fosters attachment security. Secure individuals trust that their partners will respond with love and concern, so they confidently approach interdependence dilemmas with positive expectations and pro-relationship motivations [17,18]. Secure individuals, for instance, actively seek intimacy and support from their partners when they feel vulnerable [19,20] and respond to conflicts in a constructive, relationship-promotive manner [21].

Avoidantly attached people have encountered rejection from past caregivers and believe they cannot depend on others [9]. To avoid further rebuffs, avoidant individuals defensively suppress their need for intimacy and become self-reliant [22]. Indeed, they escape the vulnerability of being dependent by not seeking support when they could benefit from it [19, 20, 23]. The interdependent reality of close relationships, however, requires avoidant individuals to address their partner's needs and preferences in some way, which can encroach on the autonomy they strive to maintain. Accordingly, avoidant individuals react with anger and withdrawal when their partners need support or try to influence them [11,24-28].

Anxiously attached people have received inconsistent care, so they crave greater acceptance and closeness while worrying that their partners might leave them [9]. This leads anxious people to become preoccupied with obtaining their partner's love and acceptance and hypervigilant to even small signs of possible rejection. Anxious individuals, therefore, become highly distressed when encountering relationship threats, such as during major conflicts with their partner [11,21,29-32] or when feeling poorly supported by their partner [19,28,33].

Attachment Insecurity and Dyadic Regulation Processes

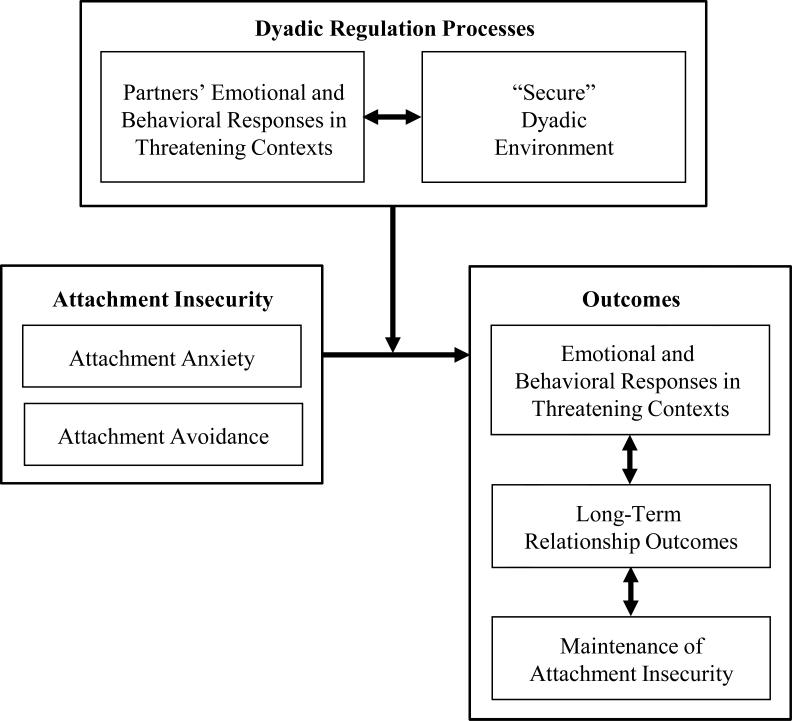

Both types of insecurity destabilize relationships [10,11,34]. However, the way in which people react to these attachment-relevant interdependence dilemmas is determined not only by the specific motives, goals, and concerns of each partner, but also by the emotional and behavioral responses of each partner during these dilemmas. Thus, the partners of insecure people can down-regulate the damaging reactions of insecure individuals if partners can assuage the worries and concerns of anxious and avoidant individuals. By improving how interdependence dilemmas are “managed”, this form of dyadic regulation—in which one partner regulates the other's responses—can yield greater security and enhance relationship well-being. Over time, the broader relationship environment can then provide a more secure dyadic context in which the down-regulation of attachment insecurity can continue (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dyadic Regulation of Attachment Insecurity.

This figure describes two dyadic regulation processes that can alter links between attachment insecurity and negative relationship outcomes. Partners can respond in ways that down-regulate the destructive reactions of insecurely attached individuals in threatening interdependent contexts. This regulation of insecurity can also generate more secure dyadic environments that counteract insecure individuals’ negative expectations. These two dyadic regulation processes tend to produce more constructive responses during threatening interactions, enhance relationship well-being, and foster greater attachment security.

The Partner's Responses in Threatening Contexts Down-Regulate Insecure Reactions

The first dyadic regulation process involves when and how the responses of partners of insecure individuals alter (moderate) their typically destructive reactions in threatening interdependence dilemmas (see Figure 1). When partners’ behaviors reaffirm the core concerns and fears of anxious or avoidant individuals, attachment-related emotional and behavioral tendencies should occur unabated and typically damage relationships. These destructive reactions, however, should be curtailed when partners address the specific concerns and needs of insecure individuals, enabling couples to traverse interdependence dilemmas more constructively and successfully.

Our program of research has identified some of the key partner responses that down-regulate insecure reactions in different interdependence dilemmas that avoidant and anxious individuals usually find threatening [see 13,14]. One situation that imposes on autonomy, which is important to avoidant people, is being the target of a partner's influence attempts [26]. Overall and colleagues [27] videotaped couples discussing relationship problems in which one partner (the agent) wanted changes in the other partner (the target). As predicted, avoidant targets reported more anger and displayed more observer-rated withdrawal when they were the target of their partner's change attempts, which hindered problem resolution. These defensive reactions, however, were ameliorated when partners behaved more sensitively to avoidant targets’ autonomy needs. Specifically, avoidant targets displayed less anger and withdrawal, and their discussions were more successful, when their partners “softened” their influence attempts by using indirect tactics that acknowledged targets’ constructive efforts and positive attributes.

Another interdependence dilemma that triggers avoidant defenses is receiving support. Avoidant individuals strive to be self-reliant, so the dependence inherent in most support exchanges triggers anger and withdrawal in them [19,20,28,35]. These defensive responses, however, are mitigated when partners provide practical forms of support that deemphasize the dependence, emotional vulnerability, and intimacy that avoidant individuals dislike. Simpson and colleagues [36] assessed how emotional and instrumental caregiving behaviors enacted by partners calmed support recipients while couples were videotaped discussing relationship problems. As predicted, more emotional caregiving (e.g., encouraging discussion of emotional experiences) predicted greater observer-rated distress in avoidant recipients. In contrast, avoidant individuals were rated as more calmed when their partners gave them more instrumental caregiving, such as concrete advice and suggestions (see also [37]).

Dilemmas that elicit relationship loss or abandonment concerns, which are salient to anxious people, frequently center on major relationship conflicts. Tran and Simpson [38] videotaped married couples discussing important aspects of one another that generated conflicts. Anxious individuals felt more negative emotions and displayed less positive observer-rated behaviors during these discussions. However, partners who were more committed to the relationship inhibited the urge to retaliate and maintained the relationship by working harder to solve the problem. These behavioral manifestations of commitment convey exactly what anxious individuals want—reassurance of their partner's love and future investment. Accordingly, when their partners were more committed, anxious individuals felt greater acceptance and behaved as positively as secure individuals did (see also [39]).

Other research also indicates that committed partners approach relationship-threatening situations in ways that ease anxious individuals’ worries and redress their reactions to threat. Lemay and Dudley [40], for example, found that individuals who perceive their partners are higher in attachment anxiety regulate their partners’ insecurities by concealing their discontent and accentuating how positively they feel about their partner. These regulation behaviors, in turn, help anxious individuals feel more valued and regarded on a daily basis.

In summary, when partners meet the specific needs and concerns of avoidant and anxious individuals, they can buffer relationships from their typical destructive reactions, sometimes turning precarious interdependence dilemmas into opportunities for relationship growth [14]. As shown in Figure 1, by constantly creating constructive interactions and outcomes in threatening situations, effective dyadic regulation can also improve relationships over time. Supporting this premise, Salvatore and colleagues [41] demonstrated that when adult romantic partners behave more positively during post-conflict discussions (showing they can “move on” and recover from conflict), individuals who were insecure in childhood felt better about their relationship, and their relationships were more likely to be intact two years later. Overall and colleagues [32] also illustrated that anxious individuals feel more secure and satisfied over time when their partners’ emotional responses during conflict convey greater commitment.

“Secure” Dyadic Environments Bolster Satisfaction and Attachment Security

Partner responses that allay destructive reactions in threatening situations should have positive long-term effects to the extent they generate more secure dyadic environments that counteract insecure individuals’ negative expectations (see Figure 1). The more insecure individuals receive evidence that their partners are reliable and sensitive to their specific needs, the more they should come to view their relationships as stable and their partners as “truly being there” for them. Moreover, the realization that their relationship is a “safe haven” in times of need and a “secure base” from which to navigate life ought to increase relationship satisfaction, improve relationship maintenance, and perhaps reduce attachment insecurity [42,43].

One demonstration of these effects is research on the transition to parenthood, a chronically stressful period of life when partners become more interdependent [44]. Perceptions of the partner and relationship are critical to understanding how well anxious and avoidant individuals weather this difficult life transition. If anxious women perceive their partners are less supportive during the transition, they report declines in relationship satisfaction [35,45] and become more anxious over time [46]. If, however, the dyadic context of the relationship suggests their partners are more committed and supportive, anxious women maintain their relationship satisfaction levels and become less anxious over time. Perceiving the partner as closer and more supportive also protects anxious women and men from higher depressive symptoms following childbirth [47,48]. Avoidant individuals also show better adjustment across the transition when they believe they can rely on their partners to help them in cooperative, non-intrusive ways [47].

Research examining other features of the relationship environment also reveals how the dyadic context can enhance relationship satisfaction in insecure individuals and build greater security. One important aspect of relationships that can promote bonding and convey a partner's emotional availability is sexual activity. When anxious people have satisfying sex, they anticipate their partners will be more affectionate and dependable in the future, which improves marital satisfaction [49]. More frequent sex also helps avoidant people maintain more positive evaluations of their marriages [49]. Finally, avoidant people report reductions in avoidance when they believe they can trust their partners to be available and reliable when needed, whereas anxious people report reductions in anxiety when they believe their partners value and support their personal goals [50]. Thus, when the dyadic environment contradicts the negative expectations of insecurely attached people, thereby conveying that the relationship is a safe haven and secure base, anxious and avoidant people tend to become more secure across time.

Conclusions

Interdependence dilemmas can pose difficulties, particularly for insecurely attached people who struggle with trusting that their partners have their best interests at heart. However, these dilemmas also allow partners to change the way insecure tendencies manifest in these situations, which helps insecure people develop more trusting and secure perceptions. This is accomplished when partners effectively down-regulate the prototypical reactions of avoidant and anxious individuals in certain threatening contexts. These responses also provide diagnostic evidence that partners can be relied on—and can create the type of secure dyadic environment— that eventually fosters more relationship satisfaction and greater attachment security.

Highlights.

Insecurely attached people have relatively unhappy and unstable romantic relationships

But, partners can down-regulate the emotional and behavioral reactions of insecure people

Partners’ regulation produces more constructive relationship interactions

Partners’ regulatory responses also create a more secure relationship environment

These dyadic regulation processes can enhance relationship well-being and attachment security

Acknowledgements

Some of the research cited in this article was supported by grants from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund (UOA0811) to Nickola C. Overall, and from the National Institute of Mental Health to Jeffry A. Simpson (R01-MH49599).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nickola C. Overall, University of Auckland

Jeffry A. Simpson, University of Minnesota

References

- 1.Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal relations. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley HH, Holmes JG, Kerr NL, Reis HT, Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. An atlas of interpersonal situations. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rusbult CE, Van Lange PAM. Interdependence, interaction and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:351–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray SL, Holmes JG, Collins NL. Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:641–666. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. 2: Separation. Basic Books; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3: Loss. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck L, Clark MS. Choosing to enter or to evade socially diagnostic situations. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1175–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 35. Academic Press; New York: 2003. pp. 53–152. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01002-5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- **11.Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Devine PG, Plant A, Olson J, Zanna M, editors. Adult attachment orientations, stress, and romantic relationships. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2012;45:279–328. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00006-8. [A comprehensive review of how different forms of stress affect securely, anxiously, and avoidantly attached individuals and their romantic relationships in different types of social situations, focusing primarily on behavioral observation studies with romantic couples.] [Google Scholar]

- *12.Overall NC, Lemay EP., Jr. Attachment and dyadic regulation processes. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and research: New directions and emerging themes. Guilford; New York: 2015. [A comprehensive review of dyadic regulation processes and attachment dynamics, including how insecure individuals try to regulate their partners.] [Google Scholar]

- *13.Overall NC, Simpson JA. Regulation processes in close relationships. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford handbook of close relationships. Oxford University Press; New York: 2013. pp. 427–451. [A general, comprehensive overview of the operation of dyadic regulation processes in romantic relationships.] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Simpson JA, Overall NC. Partner buffering of attachment insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:54–59. doi: 10.1177/0963721413510933. doi: 10.1177/0963721413510933. [A concise review of the partner responses that down-regulate insecure reactions during couples’ conflict interactions.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Stress and secure base relationships in adulthood. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 5): Attachment processes in adulthood. Kingsley; London: 1994. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Development. 1977;48:1184–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins NL. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:810–832. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins NL, Ford MB, Guichard AC, Allard LM. Working models of attachment and attribution processes in intimate relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:201–219. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins NL, Feeney BC. A safe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1053–1073. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1053. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support-seeking and support-giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:434–446. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.3.434. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Phillips D. Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:899–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. Tavistock; London: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Airport separations: A naturalistic study of adult attachment dynamics in separating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1198–1212. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming WS, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64:231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikulincer M. Adult attachment style and individual differences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overall NC, Sibley CG. Attachment and dependence regulation within daily interactions with romantic partners. Personal Relationships. 2009;16:239–261. [Google Scholar]

- **27.Overall NC, Simpson JA, Struthers H. Buffering attachment-related avoidance: Softening emotional and behavioral defenses during conflict discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:854–871. doi: 10.1037/a0031798. doi: 10.1037/a0031798. [A behavioral observation study demonstrating that partners who are sensitive to autonomy needs by “softening” influence tactics down-regulate the anger and withdrawal typically exhibited by avoidant individuals when they are targeted for change during conflict discussions.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Oriña MM. Attachment and anger in an anxiety-provoking situation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:940–957. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.940. doi: 10.1037/ 0022-3514.76.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry J, Kashy DA. Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:510–531. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feeney JA, Noller P, Callan VJ. Attachment style, communication and satisfaction in the early years of marriage. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. Jessica Kingsley; London: 1994. pp. 269–308. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scharfe E, Bartholomew K. Accommodation and attachment representations in young couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- **32.Overall NC, Girme YU, Lemay EP, Hammond MD. Attachment anxiety and reactions to relationship threat: the benefits and costs of inducing guilt in romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014;106:235–256. doi: 10.1037/a0034371. doi: 10.1037/a0034371. [Two longitudinal studies demonstrating that highly anxious individuals respond with greater hurt feelings when encountering conflict, but when partners respond to conflict and expressions of hurt with emotions that convey commitment (e.g., guilt), anxious individuals become more satisfied and secure in their relationship over time.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeney JA. Adult romantic attachment: Developments in the study of couple relationships. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. The handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2nd edition Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 456–481. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Campbell L, Grich J. Adult attachment and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:421–435. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.3.421. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **36.Simpson JA, Winterheld HA, Rholes WS, Oriña MM. Working models of attachment and reactions to different forms of caregiving from romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:466–477. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.466. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.466. [A behavioral observation study demonstrating that instrumental, but not emotional, forms of caregiving reduces the distress of avoidantly attached individuals.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikulincer M, Florian V. Are emotional and instrumental supportive interactions beneficial in times of stress? The impact of attachment style. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 1997;10:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- **38.Tran S, Simpson JA. Pro-relationship maintenance behaviors: The joint roles of attachment and commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:685–698. doi: 10.1037/a0016418. doi: 10.1037/a0016418. [A behavioral observation study illustrating how partner's commitment and accommodating behaviors help anxiously attached individuals feel and behave more constructively during conflict discussions.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tran S, Simpson JA. Attachment, commitment, and relationship maintenance: When partners really matter. In: Campbell L, La Guardia JG, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. The science of the couple: The Ontario Symposium. Vol. 12. Psychology Press; New York: 2012. pp. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- **40.Lemay EP, Jr., Dudley KL. Caution: Fragile! Regulating the interpersonal security of chronically insecure partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:681–702. doi: 10.1037/a0021655. doi: 10.1037/a0021655. [Several studies demonstrating that partners intentionally regulate insecure individuals’ relationship perceptions by concealing negative sentiments and exaggerating affection.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **41.Salvatore JE, Kuo SI, Steele RD, Simpson JA, Collins WA. Recovering from conflict in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Psychological Science. 2011;22:376–383. doi: 10.1177/0956797610397055. doi: 10.1177/0956797610397055. [Based on the Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Risk and Adaptation, this study demonstrates that partners who recover from conflict quickly are able to sustain relationships with people who were insecurely attached in childhood.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feeney BC. A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feeney BC, Thrush RL. Relationship influences on exploration in adulthood: The characteristics and function of a secure base. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:57–76. doi: 10.1037/a0016961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change in couples. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohn JL, Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Martin AM, Tran S, Wilson CL. Changes in marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: The role of adult attachment orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:1506–1522. doi: 10.1177/0146167212454548. doi: 10.1177/0146167212454548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Wilson CL. Changes in attachment orientations across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:317–331. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00030-1. [Google Scholar]

- **47.Rholes WS, Simpson JA, Kohn JL, Wilson CL, Martin AM, Tran S, Kashy DA. Attachment orientations and depression: A longitudinal study of new parents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:567–586. doi: 10.1037/a0022802. doi: 10.1037/a0022802. [A longitudinal study revealing that anxious and avoidant individuals show better adjustment across the transition to parenthood when they perceive their partner is a supportive spouse (for anxiety) or provides them with cooperative, non-intrusive caregiving (for avoidance).] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Tran S, Wilson CL. Adult attachment, the transition to parenthood, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1172–1187. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1172. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **49.Little KC, McNulty JK, Russell M. Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:484–498. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. [A study of married couples showing that satisfying and frequent sexual activity boosts expectations of partner availability, which reduces negative associations between attachment insecurity and martial satisfaction.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **50.Arriaga XB, Kumashiro M, Finkel EJ, VanderDrift LE, Luchies LB. Filling the void: Bolstering attachment security in committed relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2014;5:398–406. doi: 10.1177/1948550613509287. [A longitudinal study showing that perceiving the partner as supportive of personal goals and trusting the partner predicts reductions in attachment anxiety and avoidance, respectively.] [Google Scholar]