Abstract

Purpose

Diencephalic syndrome is an uncommon cause of failure to thrive in early childhood that is associated with central nervous system neoplasms in the hypothalamic-optic chiasmatic region. It is characterized by complex signs and symptoms related to hypothalamic dysfunction; such nonspecific clinical features may delay diagnosis of the brain tumor. In this study, we analyzed a series of cases in order to define characteristic features of diencephalic syndrome.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of 8 patients with diencephalic syndrome (age, 5-38 months). All cases had presented to Seoul National University Children's Hospital between 1995 and 2013, with the chief complaint of poor weight gain.

Results

Diencephalic syndrome with central nervous system (CNS) neoplasm was identified in 8 patients. The mean age at which symptoms were noted was 18±10.5 months, and diagnosis after symptom onset was made at the mean age of 11±9.7 months. The mean z score was -3.15±1.14 for weight, -0.12±1.05 for height, 1.01±1.58 for head circumference, and -1.76±1.97 for weight-for-height. Clinical features included failure to thrive (n=8), hydrocephalus (n=5), recurrent vomiting (n=5), strabismus (n=2), developmental delay (n=2), hyperactivity (n=1), nystagmus (n=1), and diarrhea (n=1). On follow-up evaluation, 3 patients showed improvement and remained in stable remission, 2 patients were still receiving chemotherapy, and 3 patients were discharged for palliative care.

Conclusion

Diencephalic syndrome is a rare cause of failure to thrive, and diagnosis is frequently delayed. Thus, it is important to consider the possibility of a CNS neoplasm as a cause of failure to thrive and to ensure early diagnosis.

Keywords: Failure to thrive, Pituitary diencephalic syndrome, Brain neoplasms, Optic nerve glioma, Astrocytoma

Introduction

Failure to thrive is a condition commonly observed by primary care physicians. It may be caused by medical problems or factors in the child's environment, such as child abuse or neglect. There is no consensus on which specific anthropometric criteria should be used to define failure to thrive1). It is often defined as a weight-for-age value that falls below the fifth percentile on multiple occasions or weight deceleration that crosses 2 major percentile lines on a growth chart2,3).

Diencephalic syndrome is a rare cause of failure to thrive in infants and young children. It is associated with neoplastic lesions of the hypothalamic-optic chiasmatic region4). This syndrome is characterized by profound emaciation, despite a normal or slightly diminished calorie intake. Linear growth is usually maintained4,5). Other features include hyperalertness, hyperkinesia, euphoria, nystagmus, hydrocephalus, visual field defects, optic pallor, emesis, and vomiting6,7,8,9). The onset of clinical symptoms is almost always within the first 3 years of life6).

Because most patients experience nonspecific symptoms and signs, it is difficult to make an early diagnosis of this syndrome. To emphasize the importance of early identification of diencephalic syndrome as a cause of failure to thrive in early childhood, we analyzed a series of cases to define characteristic features to help early diagnosis of diencephalic syndrome.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed diencephalic syndrome patients who presented to Seoul National University Children's Hospital between 1995 and 2013. The relevant Institutional Review Boards approved this study. Over an 18-year period, diencephalic syndrome was identified in 8 patients with chief complaints of poor weight gain.

Patient height, weight, head circumference, and weight-for-height were calculated using L (Box-Cox power), M (median), and S (coefficient of variation, CV) values presented in the 2007 Korean National Growth Charts. The z-score transformations were performed using the LMS method.

Failure to thrive was defined as a weight-for-age values that falls below the fifth percentile (z score below -1.64) on multiple occasions, or weight deceleration that crosses 2 major percentile lines on a growth chart. Eight patients met the criteria for diencephalic syndrome with hypothalamic neoplasms.

Laboratory tests were performed to evaluate the nutritive status of the patients. Complete blood cell counts, fasting blood sugar levels, and serum total protein/albumin levels were obtained. Thyroid hormone levels were examined to evaluate thyroid function. Imaging studies were performed in patients. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to evaluate the cause of failure to gain weight, and findings showed evidence of central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms. Surgical biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Brain tumor biopsy samples were available from 7 patients.

Results

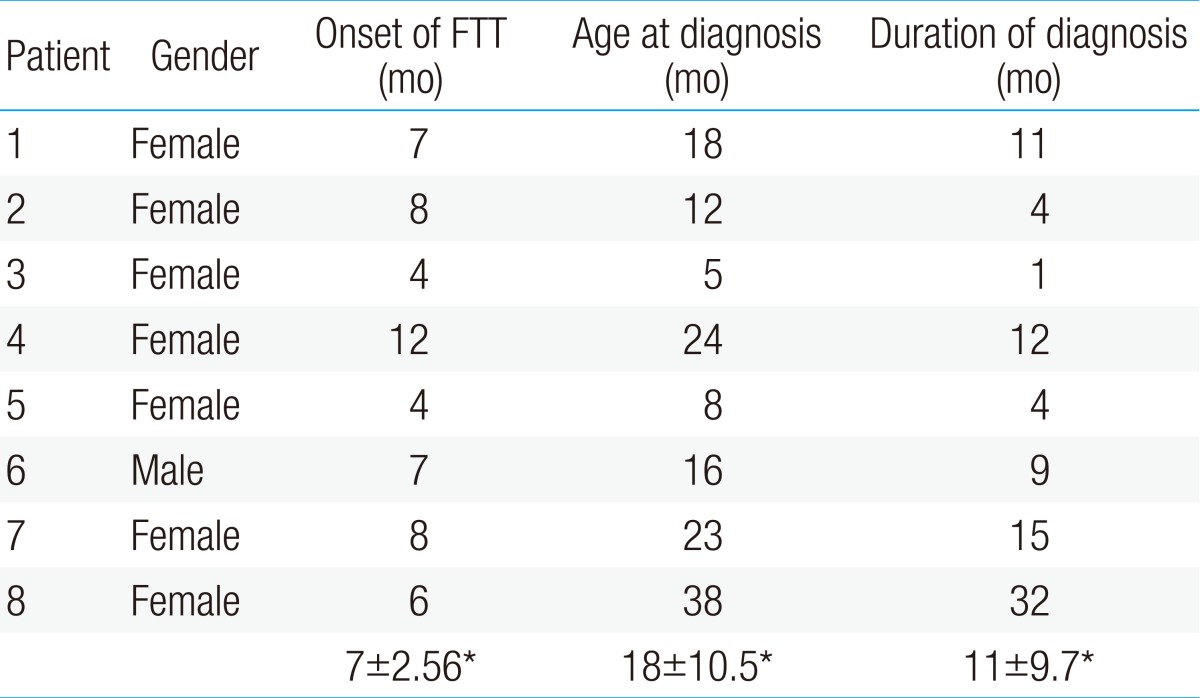

Between 1995 and 2013, diencephalic syndrome and hypothalamic-optic chiasmatic neoplasms were identified in 8 patients (1 male and 7 female patients) (Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis was 18±10.5 months (range, 5-38 months). Onset of failure to thrive was defined as the age at which the patient was initially documented to have crossed weight percentiles. The mean age at which onset of failure to thrive symptoms began was 7±2.56 months. Diagnosis was made at a mean of 11±9.7 months after the onset of symptoms.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

FTT, failure to thrive.

*Mean±standard deviation.

It took 32 months for the confirmed diagnosis of brain tumor in patient 8. At the time of initial presentation, with a history of recurrent vomiting after upper respiratory tract infection, her upper gastrointestinal series results revealed chronic gastric volvulus. Surgical treatment was performed, but her symptoms did not improved. Further evaluations were recommended but her parents refused to undertake any more evaluations and discharged from the hospital. A year later, she readmitted with the symptoms of chronic vomiting and failure to thrive. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was done and prepylolic web was detected. Prepyloric web resection was performed but vomiting remained persistent. Therefore, brain MRI was performed to evaluate other cause of vomiting and failure to thrive. Hypothalamic neoplasm was detected with hydrocephalus.

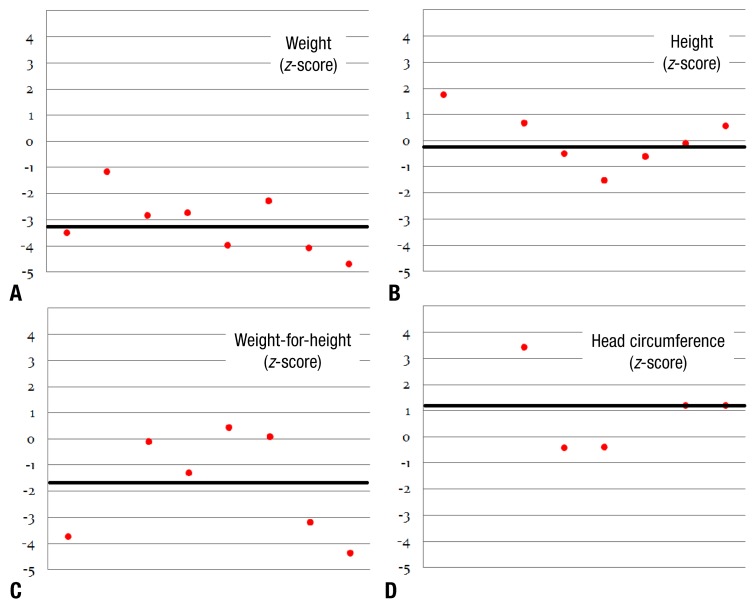

At presentation, all patients had a history of failure to thrive and an inability to gain weight despite normal or slightly decreased calorie intake. Physical examination revealed that all patients were markedly emaciated. The average z score was -3.15±1.14 for weight, -0.12±1.05 for height, 1.01±1.58 for head circumference, and -1.76±1.97 for weight-for-height (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The z scores at the time of diagnosis. (A) z score for weight, -3.15±1.14; (B) z score for height, -0.12±1.05; (C) z score for weight-for-height, -1.76±1.97; and (D) z score for head circumference, 1.01±1.58.

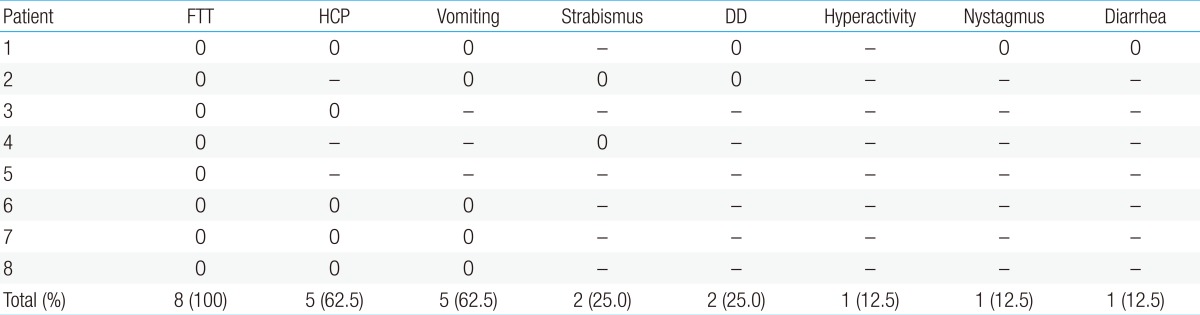

All patients met the diagnostic criteria for failure to thrive. Persistent vomiting occurred in 5 patients (62.5%) (Table 2). Hydrocephalus was noted in 5 patients (62.5%). Hyperactivity was reported in 2 patients (25%). Ophthalmologic evaluations revealed strabismus in 2 patients (25%) and nystagmus in 1 patient (12.5%). Two patients (25%) had developmental delay. One patient (12.5%) had severe diarrhea at presentation.

Table 2. Clinical symptoms and signs present in 8 patients with diencephalic syndrome.

FTT, failure to thrive; HCP, hydrocephalus; DD, developmental delay.

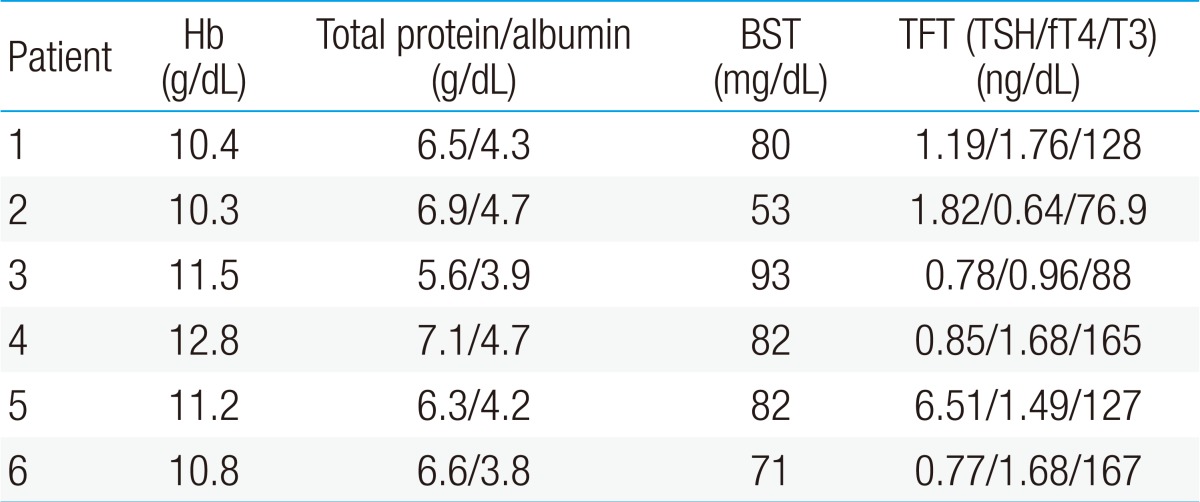

Blood tests were performed in 6 patients (Table 3). None of the patients had anemia or hypoalbuminemia. Fasting blood sugar levels were measured, and no patient showed hypoglycemia. Thyroid hormone levels were within normal limits in all patients. Preoperative pituitary function tests were not done, since most of the patients needed to ungergo urgent tumor removal.

Table 3. Laboratory results of 8 patients with diencephalic syndrome.

Six patients underwent further blood tests for evaluation of their nutritive and endocrinologic status; no abnormal results were reported.

Hb, hemoglobin; BST, blood sugar test; TFT, thyroid function test; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; fT4, free T4.

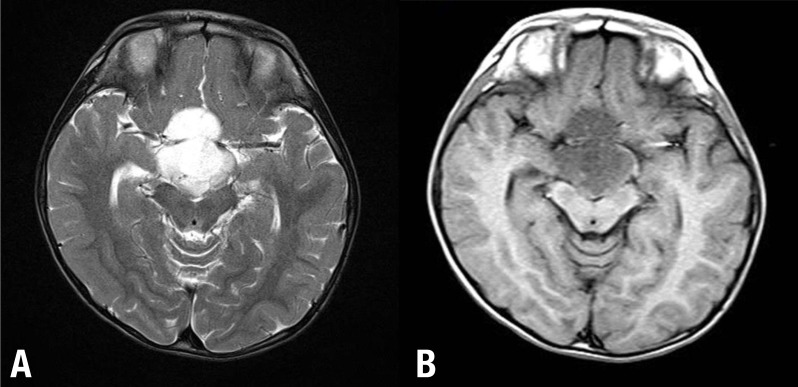

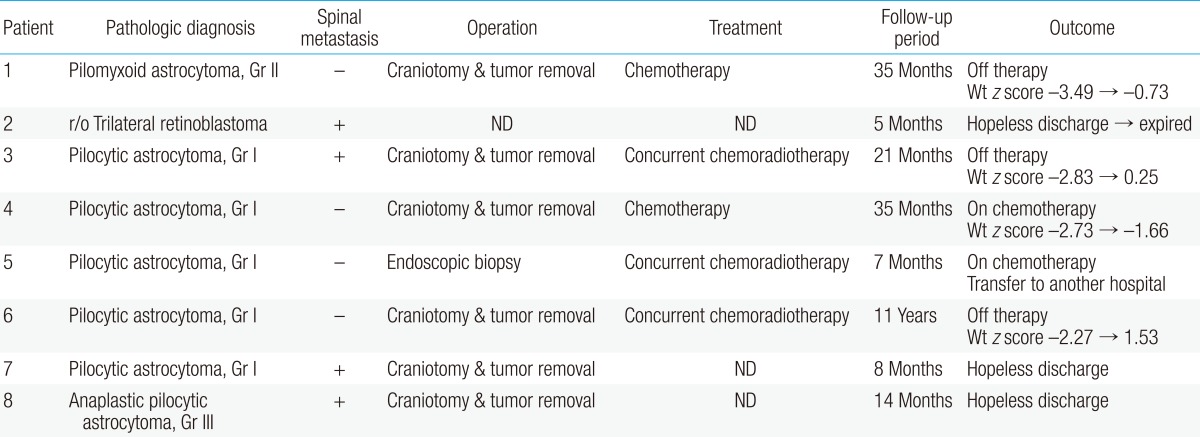

Brain MRI showed evidence of CNS neoplasms. All brain tumors involved the hypothalamus and optic-chiasm (Fig. 2). Hydrocephalus occurred in 5 patients. Biopsy specimens of hypothalamic masses were available from 7 patients (Table 4). Five patients were diagnosed with pilocytic astrocytoma (World Health Organization [WHO] grade I), 1 patient with pilomyxoid astrocytoma (WHO grade II), and 1 patient with pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade III). One patient refused biopsy, and his imaging findings suggested a diagnosis of trilateral retinoblastoma. Four of the 8 patients had spinal seeding at the time of presentation. Three patients with spinal seeding noted at presentation were in the progressive disease state at the time of diagnosis; therefore, they could not receive any treatment and were hopelessly discharged.

Fig. 2. Patient 4: A 23-month-old infant with failure to thrive. The brain magnetic resonance imaging shows well-defined high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (A), and low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, with a heterogeneous enhancing tumor in the suprasellar area, extendinginto the third ventricle (B).

Table 4. Pathologic diagnosis, treatment course, and outcome of 8 patients with diencephalic syndrome.

r/o, rule out; Wt, weight; ND, not done.

Surgical interventions, chemotherapy, and radiation treatment varied on the basis of the location and extent of the tumor. Six patients had an initial subtotal resection. One patient only underwent a biopsy of the primary tumor site. Three patients received concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and 2 patients received chemotherapy. Three patients did not receive any treatment.

On follow-up evaluation, 2 patients were still receiving chemotherapy, and 3 patients showed improvement and remained in stable remission. Three patients who were in the progressive disease state at the time of diagnosis were hopelessly discharged and did not undergo follow-up evaluation. We were able to obtain follow-up weights and heights of four patients at outpatient clinic. All of them showed improvement of z score for weight.

Discussion

Diencephalic syndrome, or Russell's syndrome, was first described by Russell4). It is characterized by major features (severe emaciation despite normal or slightly decreased caloric intake, locomotor hyperactivity, and euphoria) and minor features (skin pallor without anemia, hypoglycemia, and hypotension). The tumors most often associated with diencephalic syndrome are optic and hypothalamic astrocytomas4,5,6,10,11,12,13).

The initial symptom of this syndrome in patients is severe emaciation despite adequate calorie intake. In our study, blood test results showed that none of the patients had any significant abnormalities that suggested chronic malnutrition. Failure to thrive, the hallmark of diencephalic syndrome, has been reported in previous cases4,5,6,14). In our study, all patients met the criteria for failure to thrive. Their weight-for-age values were below the fifth percentile on the growth chart, whereas their height-for-age values were within the normal range. The head circumference values of the patients were above normal, probably owing to the presence of hydrocephalus. Onset of failure to thrive in the majority of the reported cases occurred in the first year of life4,5,13,15,16). In our study, the initial symptom of failure to thrive occurred at an average of 7 months of age.

The mechanisms of failure to thrive in diencephalic syndrome are not fully explained. Pathogenesis of weight loss in diencephalic syndrome was proposed in previous studies. The hypothesis included an elevated growth hormone (GH) level with a paradoxic response to a glucose load, partial GH resistance, and excessive β-lipotropin (a lipolytic peptide) secretion, resulting in increased lipolysis and subsequent loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue17,18). Furthermore, an increase in energy expenditure which affected growth and weight has also been reported in diencephalic sydrome19).

There are various clinical manifestations of diencephalic syndrome. Visual symptoms and signs such as nystagmus, decreased visual fields, and optic pallor occur in 56%-66% of the cases3,11,20). In our study, nystagmus was observed in 1 patient (12.5%). Locomotor hyperactivity, as described in the report by Russell4), was found in 2 patients (25%).

Previous studies show that most of the children had extensive clinical work-up before being diagnosed with diencephalic syndrome21). In our study, the diagnosis of diencephalic syndrome was made at a mean of 11 months after the onset of symptoms. A delay in diagnosis may occur because brain tumor is not considered early. Therefore, diencephalic syndrome should be considered as a differential diagnosis in any child with failure to gain weight with normal linear growth, and imaging studies should be performed even if there are no additional neurological symptoms.

Treatment of optic and hypothalamic astrocytoma includes surgical resection, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Total surgical resection of an astrocytoma is rarely possible because of the anatomic location of the tumor. Radiation therapy in early childhood often results in intellectual and endocrinologic sequelae, and thus, this modality is often postponed for young children22). Therefore, chemotherapy appears to play a major role in the management of diencephalic syndrome in young children23,24,25,26). In our study, patients who received proper treatment showed resolution of diencephalic syndrome with normal weight gain.

In conclusion, the characteristic clinical features of diencephalic syndrome may serve as vital clues to clinicians in the diagnosis of this syndrome. Diencephalic syndrome is rare but potentially morbid and general pediatricians should have a high and early index of suspicion of CNS neoplasms as a cause of unexplained failure to thrive in early childhood.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Gahagan S. Failure to thrive: a consequence of undernutrition. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:e1–e11. doi: 10.1542/pir.27-1-e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen EM, Petersen J, Skovgaard AM, Weile B, Jorgensen T, Wright CM. Failure to thrive: the prevalence and concurrence of anthropometric criteria in a general infant population. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:109–114. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.080333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen EM. Failure to thrive: still a problem of definition. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45:1–6. doi: 10.1177/000992280604500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell A. A diencephalic syndrome of emaciation in infancy and childhood. Arch Dis Child. 1951;26:274. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addy DP, Hudson FP. Diencephalic syndrome of infantile emaciation. Analysis of literature and report of further 3 cases. Arch Dis Child. 1972;47:338–343. doi: 10.1136/adc.47.253.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burr IM, Slonim AE, Danish RK, Gadoth N, Butler IJ. Diencephalic syndrome revisited. J Pediatr. 1976;88:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pimstone BL, Sobel J, Meyer E, Eale D. Secretion of growth hormone in the diencephalic syndrome of childhood. J Pediatr. 1970;76:886–889. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenes D, Woods M. A 4-month-old boy with severe emaciation, normal linear growth, and a happy affect. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996;8:50–57. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bain HW, Darte JM, Keith WS, Kruyff E. The diencephalic syndrome of early infancy due to silent brain tumor: with special reference to treatment. Pediatrics. 1966;38:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danziger J, Bloch S. Hypothalamic tumours presenting as the diencephalic syndrome. Clin Radiol. 1974;25:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(74)80118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeSousa AL, Kalsbeck JE, Mealey J, Jr, Fitzgerald J. Diencephalic syndrome and its relation to opticochiasmatic glioma: review of twelve cases. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:207–209. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelc S, Flament-Durand J. Histological evidence of optic chiasma glioma in the "diencephalic syndrome". Arch Neurol. 1973;28:139–140. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490200087015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelc S. The diencephalic syndrome in infants. A review in relation to optic nerve glioma. Eur Neurol. 1972;7:321–334. doi: 10.1159/000114436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markesbery WR, McDonald JV. Diencephalic syndrome. Long-term survival. Am J Dis Child. 1973;125:123–125. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1973.04160010085021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dods L. A diencephalic syndrome of early infancy. Med J Aust. 1967;1:222–227. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1967.tb21159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond EF, Averick N. Marasmus and the diencephalic syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1966;14:270–272. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1966.00470090042005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drop SL, Guyda HJ, Colle E. Inappropriate growth hormone release in the diencephalic syndrome of childhood: case report and 4 year endocrinological follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1980;13:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1980.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleischman A, Brue C, Poussaint TY, Kieran M, Pomeroy SL, Goumnerova L, et al. Diencephalic syndrome: a cause of failure to thrive and a model of partial growth hormone resistance. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e742–e748. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlachopapadopoulou E, Tracey KJ, Capella M, Gilker C, Matthews DE. Increased energy expenditure in a patient with diencephalic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1993;122:922–924. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(09)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poussaint TY, Barnes PD, Nichols K, Anthony DC, Cohen L, Tarbell NJ, et al. Diencephalic syndrome: clinical features and imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1499–1505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldbloom RB. Failure to thrive. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1982;29:151–166. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffner PK. Long-term effects of radiation therapy on cognitive and endocrine function in children with leukemia and brain tumors. Neurologist. 2004;10:293–310. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000144287.35993.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamberlain MC, Levin VA. Chemotherapeutic treatment of the diencephalic syndrome. A case report. Cancer. 1989;63:1681–1684. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900501)63:9<1681::aid-cncr2820630906>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gropman AL, Packer RJ, Nicholson HS, Vezina LG, Jakacki R, Geyer R, et al. Treatment of diencephalic syndrome with chemotherapy: growth, tumor response, and long term control. Cancer. 1998;83:166–172. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<166::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato T, Sawamura Y, Tada M, Ikeda J, Ishii N, Abe H. Cisplatin/vincristine chemotherapy for hypothalamic/visual pathway astrocytomas in young children. J Neurooncol. 1998;37:263–270. doi: 10.1023/a:1005866021835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuper A, Bloch I, Kornreich L, Horev G, Michowitz S, Zaizov R, et al. Successful chemotherapeutic treatment of diencephalic syndrome with continued tumor presence. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;13:443–449. doi: 10.3109/08880019609030856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]