Abstract

Patient: Female, 33

Final Diagnosis: Acute porphyria

Symptoms: Abdominal pain • alternating bowel habits

Medication: Metronidazole • bactrim • oxybutynin

Clinical Procedure: EMG • porhyria workup

Specialty: Neurology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Acute porphyria and Arnold Chiari malformation are both uncommon genetic disorders without known association. The insidious onset, non-specific clinical manifestations, and precipitating factors often cause diagnosis of acute porphyria to be missed, particularly in patients with comorbidities.

Case Report:

A women with Arnold Chiari malformation type II who was treated with oxybutynin and antibiotics, including Bactrim for neurogenic bladder and recurrent urinary tract infection, presented with non-specific abdominal pain, constipation, and diarrhea. After receiving Flagyl for C. difficile colitis, the patient developed psychosis, ascending paralysis, and metabolic derangements. She underwent extensive neurological workup due to her congenital neurological abnormalities, most of which were unremarkable. As a differential diagnosis of Guillain Barré syndrome, acute porphyria was then considered and ultimately proved to be the diagnosis. After hematin administration and intense rehabilitation, the patient slowly recovered from the full-blown acute porphyria attack.

Conclusions:

This case report, for the first time, documents acute porphyria attack as a result of a sequential combination of 3 common medications. This is the first case report of the concomitant presence of both acute porphyria and Arnold Chiari malformation, 2 genetic disorders with unclear association.

MeSH Keywords: Arnold-Chiari Malformation; Guillain-Barre Syndrome; Porphyria, Acute Intermittent

Background

Acute porphyria is a debilitating disorder caused by accumulation of intermediates of heme as a result of enzyme deficiency in heme synthesis [1]. The relative rarity, insidious onset, and broad spectrum of clinical manifestations may result in a missed diagnosis, with devastating sequelae [2]. Arnold Chiari malformation type II is a rare congenital disease characterized by displacement of part of the cerebellum and brain stem into the foramen magnum, usually accompanied by myelomeningocele. Neurological manifestations involve cranial nerves, sensory, motor, and balance [3,4]. Surgeries, including ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VP shunt) for hydrocephalus, are definitive treatment [3]. The concomitant presence of both of these 2 rare diseases has not been documented previously in the literature. We report an unusual case of acute porphyria in a patient with Arnold Chiari syndrome.

Case Report

We report a 33-year-old Venezuelan woman with Arnold Chiari malformation type II status after VP shunt in infancy, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4 caused by hydronephrosis secondary to neurogenic bladder, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI), admitted with abdominal pain, and alternating bowel habits. She developed acute kidney injury (AKI) due to severe hydronephrosis and an episode of UTI 2 months prior to the current admission. She took oxybutynin for bladder spasm and iron for 2 months, and she also took sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (Bactrim) 2 weeks ago. She was admitted 12 days prior to the current admission for epigastric abdominal pain, back pain, AKI, and UTI.

The patient had 2 more ED visits in 9 days for abdominal pain and constipation alternating with diarrhea, which led to her current admission. Beside atrophic lower extremities due to her known spina bifida, physical exam was only significant for mild, diffuse, vague, abdominal tenderness without rebound. Laboratory test results were consistent with chronic mild normocytic anemia and CKD stage 4. Abdominal CT did not reveal acute abnormalities. Constipation was considered to be an adverse effect of oxybutynin and iron replacement, thus both were discontinued. C. difficile colitis was suspected and metronidazole was started. Her abdominal pain improved on day 2 of admission.

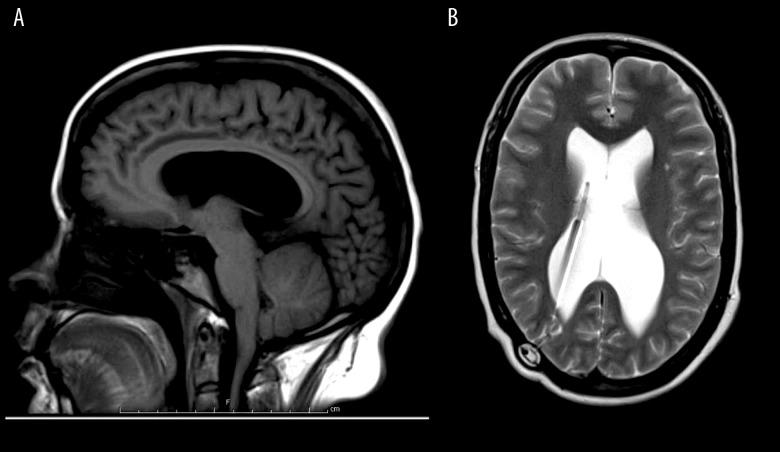

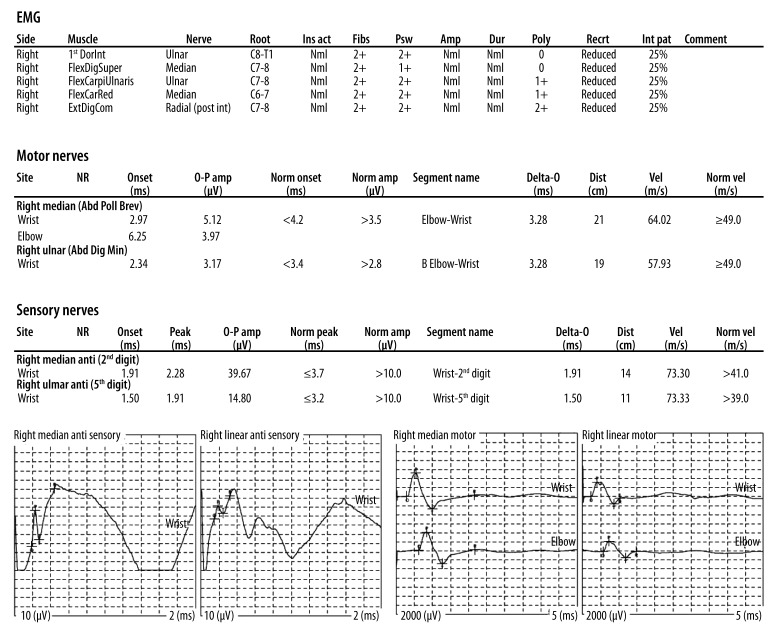

However, on day 3 she developed acute-onset slurred speech, visual hallucination and delirium, decreased motor strength with 4/5 in upper extremities and 3/5 in lower extremities, hyper-reflexia in upper extremities, tachycardia, and hypertension. Since metronidazole is known to cause neurotoxicity [5], it was discontinued immediately. The differential diagnosis included variants of Guillain Barré syndrome (GBS), hydrocephalous due to VP shunt failure, and central nervous system infection with acute porphyria as a differential to rule out. Head CT (Figure 1) and brain MRI (Figure 2) revealed chronic compensated hydrocephalous secondary to known VP shunt disruption without acute abnormalities. Lumbar puncture demonstrated an elevated open pressure at 270 mm H2O but was negative for albuminocytological dissociation, oligoclonal bands, virology series (enterovirus, HSV, VZV, CMV, and West Nile), Lyme disease, and cultures. In the next 2 days her neurological abnormalities persisted and hyper-reflexia changed to hypo-reflexia. We then seriously considered acute porphyria given her recurrent abdominal symptoms, medication history, and manifestations of acute porphyria overlapping with GBS [2,6]. The patient’s quadriplegia continued to deteriorate while awaiting test results: motor strength decreased to 2/5 in all extremities and electromyogram of the right arm revealed severe peripheral axonal polyneuropathy (Figure 3). Meanwhile, she manifested type 4 renal tubule acidosis, hyponatremia, and hypomagnesemia. The test result for C. difficile was positive and oral vancomycin regimen was started.

Figure 1.

Head CT without contrast. 1. Mechanical disruption of the right VP shunt. 2. Mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles on both sides. 3. Mild low-lying with cerebellar tonsils, which may have a mild mass effect on the floor of the fourth ventricle.

Figure 2.

Brain MRI without contrast. (A) sagittal T1; (B) axial T2. 1. A VP shunt with its tip within the right lower ventricle.

2. Ventricomegaly involving the lateral ventricles, most pronounced within the atria. 3. Beaked appearance of the tectum.

4. The tonsils are slightly low-lying, with a beaked appearance.

Figure 3.

EMG. Findings: The right median and ulnar motor nerves revealed normal distal latencies, amplitudes, and conduction velocities. The right median and ulnar sensory nerves revealed normal distal latencies, amplitudes, and conduction velocities. Needle examination was performed with a monopolar disposable needle electrode on the muscles indicated above. Impression: The above electrodiagnostic study is compatible with a severe, axonal, peripheral neuropathy involving the right upper extremity.

The final porphyria test result returned on hospital day 10. Urine porphobilinogen levels collected in 3 different days were markedly elevated by 10-fold to 20-fold, urine total porphyrins level was moderately elevated by 7-fold, and levels of delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), heptacarboxylporphyrin, pentacarboxyporphyrin, and coproporphyrin were mildly elevated (Table 1). Acute porphyria was diagnosed, with acute intermittent porphyria as the working diagnosis. Hemin was administered immediately and Panhematin 250 mg/35 ml IV daily was administered for 5 days, with unremarkable improvement of motor strength. Therefore, a second 5-day course of Hemin was administered, resulting in modest improvement of upper-extremity strength. Meanwhile, urine porphobilinogen level decreased to 0 after the 10-day Hemin treatment, and the levels of other heme intermediates decreased as well (Table 1). Then, the patient received 2-month intensive inpatient rehabilitation. Upon discharge, her constipation resolved; her motor strength improved to 4/5 in the upper extremities and 4-/5 in the lower extremities. She was provided with a drug safety list and consulted regarding genetic tests for her and her family members, and genetic tests are still under consideration by the patient and her family.

Table 1.

Levels of Heme intermediates upon diagnosis and response to Hemin treatment.

| Normal value | Upon diagnosis | After Hemin treatment** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random urine PBG | <2 mg/g creatinine | 44.6, 37, 21.7* | 0 |

| Random urine delta-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) | <5.4 mg/g creatinine | 13.2 | N/A |

| Random urine total porphyrins | 31–139 mcg/g creatinine | 1255.6 | 254.6 |

| Random urine uroporphyrins | <22 mcg/g creatinine | 416 | 167 |

| Random urine heptacarboxyporphyrin | <4.6 mcg/g creatinine | 32 | 14.2 |

| Random urine hexacarboxyporphyrin | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Random urine pentacarboxyporphyrin | <1.7 mcg/g creatinine | 65.5 | Not detected |

| Random urine coproporphyrins | 23–130 mcg/g creatinine | 742 | 73.4 |

| 24 h urine total porphyrins | 12–190 mcg/24 h | 1398.5 | N/A |

| 24 h urine uroporphyrins | 3.3–295 mcg/24 h | 525.1 | N/A |

| 24 h urine heptacarboxyporphyrin | <6.8 mcg/24 h | 38 | N/A |

| 24 h urine hexacarboxyporphyrin | Not detected | N/A | |

| 24 h urine pentacarboxyporphyrin | <4.7 mcg/24 h | 42.3 | N/A |

| 24 h urine coproporphyrins | <155 mcg/24 h | 793.1 | N/A |

Values of random samples from 3 different days;

Panhematin 250 mg/35 ml IV daily for two 5-day courses for a total of 10 days.

Discussion

We concluded that the attacks of acute porphyria occurred over a 2-month span, characterized by abdominal pain, constipation, autonomic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, psychosis, delirium, and metabolic disturbances. Medications are common exacerbating factors of acute porphyria, in part by inducing ALA synthase. The underlying mechanism is that metabolism of certain medications demands more hepatic cyto-chrome P450 enzymes, which derive from heme [1]. The attack in this patient likely resulted from the combination of oxybutynin, Bactrim, and metronidazole [7,8]. Acute porphyria was initiated by oxybutynin, precipitated by Bactrim, and became full-blown after metronidazole administration. According to the drug safety list in the Porphyria South Africa database at the Universities of Cape Town and KwaZulu-Natal (http://www.porphyria.uct.ac.za/druginfo/drug-frameset-alpha.htm), sulfamethoxazole is of high risk for porphyria, while oxybutynin and metronidazole are of high potential risk. More evidence is needed to establish the porphyria-precipitating effect of oxybutynin and metronidazole.

Acute porphyria was considered only after the patient manifested neuropsychiatric abnormalities with GBS on the differential list. Acute porphyria can mimic GBS clinically and is an important differential diagnosis of GBS [2,9]. One telltale clinical pearl is that psychiatric symptoms favor acute porphyria over GBS [2]. Autonomic dysfunction of the gastrointestinal system, including constipation and abdominal pain, is frequently present in acute porphyria [9]. When in doubt, testing for acute porphyria is recommended for suspected GBS.

The delay of the diagnosis originated from several confounding factors. Interpreting symptoms as common medication adverse effects led to missed diagnosis. Intermittent constipation and vague abdominal pain were considered to be adverse effects of oxybutynin and iron replacement in the first 3 hospital encounters; the patient’s neuropsychiatric manifestations were initially thought to be known adverse reactions to metronidazole [5]. Nevertheless, multiple ED visits warrant a thorough history and medication investigation and broad differentials.

The Arnold Chiari malformation type II with a non-functioning VP shunt was another cofounding situation and complicated the differential diagnoses [3]. The rarity of both conditions initially placed acute porphyria low on the differential list. In fact, this is the first reported case of acute porphyria in a patient with Arnold Chiari malformation, which are 2 separate genetic disorders. It is unknown whether it is just an extremely rare Mendelian-pattern recombination or if there is a linkage between these 2 genetic conditions.

Conclusions

Acute porphyria needs to be ruled-out in patients with recurrent constipation and other abdominal symptoms, particularly after initiation of new medications. Acute porphyria is also an essential differential diagnosis in patients suspected of GBS. This is the first documented case of concomitant presence of acute porphyria and Arnold Chiai formation type II, and the possible association of these 2 genetic disorders is yet to be explored.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Witt, MD for his support in diagnosis and treatment of the patient and Angeliki Stamatouli, MD for her support in continuing patient education.

Footnotes

Source of support: Bridgeport Hospital

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures.

References:

- 1.Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(6):439–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-6-200503150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albers JW, Fink JK. Porphyric neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(4):410–22. doi: 10.1002/mus.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarnat HB. Disorders of segmentation of the neural tube: Chiari malformations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;87:89–103. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)87006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell JE, Gordon A, Maloney AF. The association of hydrocephalus and Arnold-Chiari malformation with spina bifida in the fetus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1980;6(1):29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1980.tb00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snavely SR, Hodges GR. The neurotoxicity of antibacterial agents. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101(1):92–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-1-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pischik E, Kazakov V, Kauppinen R. Is screening for urinary porphobilinogen useful among patients with acute polyneuropathy or encephalopathy? J Neurol. 2008;255(7):974–79. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0779-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorchein A. Drug safety in porphyria. Lancet. 1980;2(8186):152–53. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singal AK, Anderson KE. In: GeneReviews(R) Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington Seattle; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tracy JA, Dyck PJ. Porphyria and its neurologic manifestations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;120:839–49. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4087-0.00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]