Abstract

In this study, a 3D passivated-electrode, insulator-based dielectrophoresis microchip (3D πDEP) is presented. This technology combines the benefits of electrode-based DEP, insulator-based DEP, and three dimensional insulating features with the goal of improving trapping efficiency of biological species at low applied signals and fostering wide frequency range operation of the microfluidic device. The 3D πDEP chips were fabricated by making 3D structures in silicon using reactive ion etching. The reusable electrodes are deposited on second glass substrate and then aligned to the microfluidic channel to capacitively couple the electric signal through a 100 μm glass slide. The 3D insulating structures generate high electric field gradients, which ultimately increases the DEP force. To demonstrate the capabilities of 3D πDEP, Staphylococcus aureus was trapped from water samples under varied electrical environments. Trapping efficiencies of 100% were obtained at flow rates as high as 350 μl/h and 70% at flow rates as high as 750 μl/h. Additionally, for live bacteria samples, 100% trapping was demonstrated over a wide frequency range from 50 to 400 kHz with an amplitude applied signal of 200 Vpp. 20% trapping of bacteria was observed at applied voltages as low as 50 Vpp. We demonstrate selective trapping of live and dead bacteria at frequencies ranging from 30 to 60 kHz at 400 Vpp with over 90% of the live bacteria trapped while most of the dead bacteria escape.

I. INTRODUCTION

Dielectrophoresis (DEP) is a well-known technique for moving, separating, and trapping micron scale particles.1 It is particularly useful for manipulating biological samples, which usually fall within the micron size range. One of its greatest strengths is the ability to manipulate several independent variables like signal magnitude, applied frequency, signal combinations, electrode spacing, and microstructure orientation to achieve highly selective trapping. This technique has been widely used in biological applications to characterize yeast,2 bacteria,3 and mammalian cells.4–7

Electrode based DEP (eDEP) technique is normally used to generate non-uniform electric fields in the channel.8,9 Micro-patterned electrodes in the channel generate highly localized electric fields and trapping is observed to be concentrated around the electrodes. Insulator based DEP (iDEP), on the other hand, uses insulating structures rather than embedded electrodes to generate non-uniform electric field gradients in the microchannel. iDEP devices have been employed in the past to characterize particles including bacteria, viruses, cells, and beads.10–13

Previously, three dimensional insulator-based dielectrophoresis (3D iDEP) devices have been used to increase sensitivity of iDEP devices.14 Use of 3D insulating features has been shown to increase electric field gradient and the DEP force acting on particles. Previous studies using 3D iDEP technology have been shown to effectively trap bacteria.15 Earlier work, by our group, focused on trapping and separation of particles using silicon DC-Biased iDEP devices.16 Furthermore, because silicon microfluidic devices were investigated in comparison to polymer devices, this study demonstrated greatly improved heat dissipation effects attributed to enhanced thermal dissipation properties of silicon over polymer substrates.

In this paper, a DEP technique that exploits the benefits of iDEP, eDEP, and 3D fabricated insulating microstructures is demonstrated. A three dimensional, passivated-electrode, insulator-based dielectrophoresis device (3D πDEP) is introduced for the first time. A schematic of the 3D πDEP device is shown in Figure 1. The electrodes are fabricated separately on a glass slide; they can be embedded in the channel, or capacitively coupled through a thin 100 μm glass slide, and reused over multiple runs. In this study, the electrodes were passivated through a thin 100 μm glass slide, and this offers a lot of flexibility in the design of the electrodes so as to achieve optimal electric fields across the microfluidic channel. In previous work, a three dimensional insulator-based device has been shown to demonstrate enhanced performance using a combination of DC coupled AC signals.17 In this previous work, demonstrated by our group, the electrodes were in contact with the medium. This caused the electrodes to be located farther away from the insulating microstructures responsible for generating electric field gradient. In these iDEP devices, the voltages are applied across a significant portion of the microchannel increasing the complexities due to heating effects.18,19 In the current study, electrodes are located within the vicinity of the insulating microposts to minimize heat build-up within the channel. Reduced electrode spacing minimizes the conductive path travelled by the current ultimately reducing heat generated within the microchannel. The DEP force is achieved by 3D insulating structures in the channel. In comparison to traditional iDEP devices with 2D insulating features, 3D features increase the electric field gradient, which, in turn, increases the DEP force. 100% trapping efficiency (TE) can be achieved at low applied voltages thus reducing power consumption, the adverse effects of electrothermal flow, and allowing for integration with simpler supporting electronics.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of 3D πDEP. (a) Top view showing reusable electrodes, microfluidic device, and 3D insulating features. (b) Isometric view showing material composition. (c) Front view showing the main channel.

This 3D πDEP is comparable to our previously reported passivated-electrode insulator-based dielectrophoresis (OπDEP) device.20 OπDEP combines the benefits of a high throughput, low cost 2D iDEP, and the enhanced sensitivity of eDEP with electrodes located in the vicinity of the 2D insulating microstructures. A reusable set of electrodes are activated and the signal capacitively coupled through a thin glass slide into the microfluidic channel. 3D πDEP, on the other hand, achieves high capture efficiencies at lower applied voltages and over a wider frequency range. This paper will demonstrate performance of the 3D πDEP microfluidic device by trapping live and dead Staphylococcus aureus bacterial cells. Enrichment and separation of this bacterial cell are especially important because S. aureus is an ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen, whose infections are becoming increasingly difficult to treat due to the emergence of multiple-antibiotic resistant strains in recent years.

II. THEORY

The motion of polarizable particles suspended in a dielectrically dissimilar media when subjected to a spatially non-uniform electric field is dielectrophoresis (DEP).21 Unlike electrophoresis, particles do not have to possess a net charge to be polarized by DEP forces and hence, non-conducting particles can be manipulated by DEP. The DEP force acting on a spherical particle suspended in an electrolyte is22

| (1) |

where R is the radius of the particle, εm is the permittivity of the medium, E is the local electric field, and Re [fCM] is the real part of the Clausius-Mossotti (CM) factor, which is22

| (2) |

where and are the complex permittivities of the particle and the medium, respectively. Complex permittivity is defined as22

| (3) |

Because of the complex permittivity, FDEP is a function of frequency and can take on positive or negative values depending on the CM factor Eq. (2). The polarity of the DEP force, FDEP will therefore depends on the applied signal frequency. To further understand the behaviour of biological particles under electric fields, a shell model is employed, describing a cell as a sphere of highly conductive cytoplasm encased in insulating membrane.23 At DC fields and low frequencies (f < 500 Hz), the DEP force is governed by particle size and conductivity. At high frequencies (f > 500 Hz), the complex nature of the cell significantly contributes to the DEP response. For cells with effective permittivity greater than the conductivity of the surrounding medium, a positive CM factor and thus a positive DEP force (pDEP) is experienced. Negative DEP force is experienced otherwise. A crossover frequency is determined when zero DEP force acts on the particle and it occurs when the changing DEP force transitions from pDEP to nDEP and vice versa. Since the DEP force near a crossover frequency is close to zero (it is zero when fCM = 0), this allows for particle separation using the DEP technique.

Pressure driven fluid, at a low Reynold's number, moves through the microfluidic channel and imposes a drag force on a spherical particle. This drag force is given by1

| (4) |

where R is the radius of the particle, η is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and upf is the relative velocity of the particle with respect to the fluid. To trap a particle in a DEP device, the acting DEP force must be equal to or greater than the drag force . As shown in Eq. (4), an increase in the flow rate of the medium necessitates a higher DEP force to trap the particles.

Electrical field signals are applied to the 3D πDEP device by capacitively coupling through a thin glass slide in contact with the electrode substrate into the microfluidic channel. 3D insulating Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microstructures in the centre of the microchannel create constrictions dividing the two halves of the channel, as shown in Figure 1. These PDMS microstructures have a higher impedance in comparison with the media flowing through them such that when an electric field is applied to the microfluidic device, current takes the path of least resistance—36 μm wide and 22 μm deep openings through the 3D microstructure constrictions. Because the bulk of the current is compressed through these constrictions, high electric field gradients are generated at the microposts: This is the main operating principle of iDEP devices and subsequently πDEP devices. The generated electric field gradients, which directly influence DEP force experienced in the channel, are dependent on the geometry and physical dimension gradient of the insulating structures. The ability to vary structures in three dimensions allows for constriction of electric fields and current in all dimensions thereby creating high geometric gradients. We have shown in the past that DC iDEP devices with 3D gradients generate stronger DEP forces in comparison to 2D gradient iDEP devices.16 Similarly, the new 3D πDEP devices can operate at lower applied voltages which ultimately decreases Joule heating complications that usually plague iDEP devices.24 Additionally, this limits electrothermal flow, which is a parasitic effect that creates complications in iDEP devices.25

III. METHODS AND MATERIALS

A. Numerical device modeling

A numerical model of the 3D πDEP devices is created using COMSOL Multiphysics 3.5 (COMSOL, Inc., Burlington, MA) under the AC/DC module so as to explore electric field distributions within the microchannel. A 3D COMSOL model is created for the device under investigation. The electrical conductivities used for PDMS, glass, air, and deionized water (DI) are 8.20 × 10−13 S/m, 1.25 × 10−9 S/m, 3.00 × 10−9 S/m, and 8.00 × 10−4 S/m, respectively. The electrical permittivities used for PDMS, glass, air, and deionized water are 2.65, 4.65, 1, and 80, respectively. To define boundary conditions, the electrodes are assigned AC electric potentials, while all other boundaries are defined as electrical insulation. The values for PDMS were set by the manufacturer. The numerical modelling and simulations are used to evaluate the values of ∇|E|2 as a function of position in the microchannel and applied frequency signal. This model affirms the concept in Eq. (1), showing that the DEP force experienced by a given particle in medium is proportional to ∇|E|2.

B. Device fabrication

A new process flow for the design and fabrication of the 3D πDEP is implemented in PDMS, as shown in Figure 2. Initially, a layer of thermal silicon dioxide, 0.4 μm thick, is grown at 1000 °C on a ⟨100⟩ silicon wafer. The oxide layer is used as a mask during the etch process. Using our 3D silicon micromachining technique,26–28 a photomask layout consisting of an array of rectangular openings with different sizes and aspect ratios is created (Figure 2(a)). Thereafter, photoresist (S1813) is patterned and the pattern is transferred to the oxide using an Alcatel AMS-100 Deep Reactive Ion Etcher (DRIE) with CH4 plasma. The DRIE etch exposes silicon, which is isotropically etched using SF6 plasma (Figure 2(b)). The reactive ion etch lag (RIE lag) and its dependency on the geometrical patterns of the mask layout is exploited to create 3D cavities and microposts. This technique provides three dimensional flexibility over structure formation. Next, photoresist is removed and the silicon substrate is bonded to a Pyrex wafer under vacuum (Figures 2(c) and 2(d)). The Pyrex wafer is melted at high temperatures under a furnace causing the molten glass to conform to the shape of the 3D silicon features (Figure 2(e)).27 The glass substrate master mold is left behind after the silicon substrate is etched away using KOH (Figure 2(f)). Low cost PDMS devices were mass produced using the glass master mold. Liquid PDMS (Sylgand 184 Silicon elastomer kit, Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was mixed in a 10:1 ratio of PDMS monomer and curing agent, and poured onto the glass mold (Figure 2(g)). The setup was put into a vacuum chamber for 1 h to remove gas bubbles and then cured for 8 h at 90 °C to create 3D PDMS microstructures. Subsequently, the multiple device PDMS polymer was carefully peeled off the mold, cut into single devices, and 2 mm holes were punched into microfluidic channels for fluidic ports (Figure 2(h)). The devices are sealed by plasma bonding using a Plasma Cleaner (Harrick Plasma) to a size #0 glass cover-slide (Electron Microscopy Sciences) (Figure 2(k)), which is 100 μm thick, forming the microfluidic cartridge. Notably, microfluidic devices of different designs can be created on a single wafer and fabricated at the same time. Additionally, many PDMS devices can be created from the same glass master mold, saving more resources.

FIG. 2.

3D πDEP device fabrication process flow. (a) Top view of DRIE lag mask design. (b) Pattern oxide mask and then use RIE lag 3D silicon etch. (c) Remove oxide lattice structure with BOE. (d) Anodically bond silicon to Pyrex wafer under vacuum. (e) Melt Pyrex into silicon mold. (f) Etch all silicon with KOH. (g) Pour PDMS over Pyrex master and cure. (h) Remove PDMS from glass master and punch ports. (i) Plasma bond to glass slide. (j) Evaporate electrodes on separate glass substrate. (k) Align electrodes and microfluidic device prior to experimental runs.

Electrodes were made on a separate Pyrex glass substrate using lift off technique. Photoresist (AZ9260, AZ Electronic Materials) was used to pattern the glass substrate. Thereafter, a thin layer (25 nm) of chrome and a thicker layer (200 nm) of gold were deposited using e-beam evaporation (PVD-250, Kurt J. Lesker Company). The excess metal was later removed by dissolving the photoresist in acetone (Figure 2(j)). The fabricated electrodes were 4 mm long, 6 mm wide, and 1.2 mm apart. Under experimental runs, the PDMS microfluidic chip is placed on top of the electrodes glass substrate with the 3D insulating structures aligned between the electrodes spacing (Figure 2(k)). In this configuration, the electrodes span across the entire width of the channel allowing for uniform distribution of electric fields across the 3D insulating microstructures. Over multiple experimental runs, the PDMS microfluidic device can be replaced to maintain sample purity, while the electrodes are reused. Alternatively, the electrodes can be embedded within the channel to increase device sensitivity. The two device components of the 3D πDEP device are shown in Figure 3.

FIG. 3.

Optical image of 3D πDEP device. (Top) Disposable microfluidic cartridge. (Bottom) Reusable gold electrodes.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, showing structural details of the 2 cm long microfluidic channel are shown in Figure 4. The main fluidic channel has a cross-section of 2.2 mm wide and 100 μm deep with 3D insulating microstructure obstacle, which splits up into 14 smaller channels, at the centre of the channel. The cross section of these smaller channels is 36 μm wide and 22 μm deep. Notably, the fabricated features have rounded corners acquired by silicon isotropic etching: This is in contrast to sharp edges typically found in conventional microchannels. Therefore, the 3D aspect accounts for abrupt changes in cross-sectional area without the limitation of sharp edges.

FIG. 4.

SEM of a πDEP device comprised of 3D microposts. (a) Top view of device. (b) Magnified top view showing 3D posts. (c) Cross section of the posts showing the depth change of the structures. (d) Magnified cross section showing constriction.

C. Cell preparation

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) strain (ATCC 12600) was cultured in brain heart infusion media (Bactrius Limited, Houston TX). S. aureus cells were cultured in 100 ml of broth medium at 37 °C and 165 rpm to the exponential growth phase (OD600 ∼ 0.8). Cells were then transferred into two sterile 50 ml centrifuge tubes, and subjected to five washes by centrifugation (5000× g for 10 min) and re-suspension in 1× PBS. A calibration curve relating OD600 to microscopic cell counts was created and used to quantify the washed bacteria via spectrophotometry thereafter. To express green or red fluorescence under a microscope, bacteria were stained for 20 min using a live/dead viability kit (LIVE/DEAD Backlit, Invitrogen). Prior to experimental runs, S. aureus cells were centrifuged and re-suspended 5 times in deionized water with a measured conductivity of 800 μS/m. The deionized water conductivity was measured with a solution conductivity meter (SG7, Mettler Toledo, Scherzenbach, Switzerland). The average cell concentration for experiments was 109 cells/ml.

D. Experimental setup

An AC signal of 200 V peak to peak (Vpp) was applied to the microfluidic device over a frequency range of DC to 1 MHz using a function generator (4079, BK Precision) connected to a power amplifier (Voltage Amplifier A800DI, FLC Electronics). The PDMS-based microfluidic cartridges were placed in vacuum for at least 30 min prior to experiments to counter priming issues, remove contaminants, and eliminate air bubbles in the main channel. During experimental runs, the medium was pressure driven through the 3D πDEP device, using a 1 ml syringe connected to syringe pump (Pump 11 Elite, Harvard Apparatus), to a waste reservoir. Once the device was ready for operation, medium was continually pushed through the main channel at 100 μl/h for 5 min prior to the beginning of the experiments in order to ensure steady fluid flow during operation. Because of the transparent PDMS-based microfluidic cartridge, DEP trapping efficiency of the device was observed in real time using an inverted fluorescent microscope (Axio Observer Z1) and video recording of all trapping experiments acquired using either CCD colour camera (AxioCam MRC) or a CCD monochrome camera (IDT Limited, MotionXtra NX-4) for high frame rate capture.

While maintaining a constant flow rate, for every experimental data point, a known electric signal was applied and the corresponding real time video recorded in real time. The signal was switched off after 40 s and previously trapped bacteria were released. Whenever necessary, the microchannel was cleared of fouled bacteria by increasing the flow rate of the medium. Thus, each data point accounted for bacteria trapped during that experimental run.

In order to quantify the effectiveness of the DEP trapping during experiments, light intensity measurements were conducted using Image J, an image analysis program developed by NIH. Two regions located at the microposts were selected and the intensity of fluorescent cells measured. This was quantified and compared to a region with no trapping to obtain the reported TE defined as

| (5) |

where (I) is the trapping intensity of incoming bacteria and (O) is the trapping intensity of outgoing or escaped bacteria observed in the video during trapping. These measurements were made using Image J to quantify bacteria flow upstream (I) and downstream (O) of the 3D insulating microstructures trapping region. Notably, using this software, number of individual particles trapped can be counted by analyzing the area of fluorescent trapped regions for low concentration samples or larger bioparticles such as mammalian cells. Ultimately, the trapping efficiency from intensity measurements is undervalued since particles vertically pile up on the microposts when they are trapped.

Three fluid flow velocity sweeps from 100 μl/h to 1000 μl/h were conducted to observe influence of fluid flow on DEP trapping. The final reported data point representing one flow rate correspond to values of I and O averaged over three flow sweeps. In situations where bacteria remained in clusters, the clusters were assumed to be flat and the size of the cluster was used to estimate the number of bacteria in the cluster. It should be noted that if clusters had multiple bacteria stacked in depth, then this method would underestimate the number of bacteria.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Numerical modeling

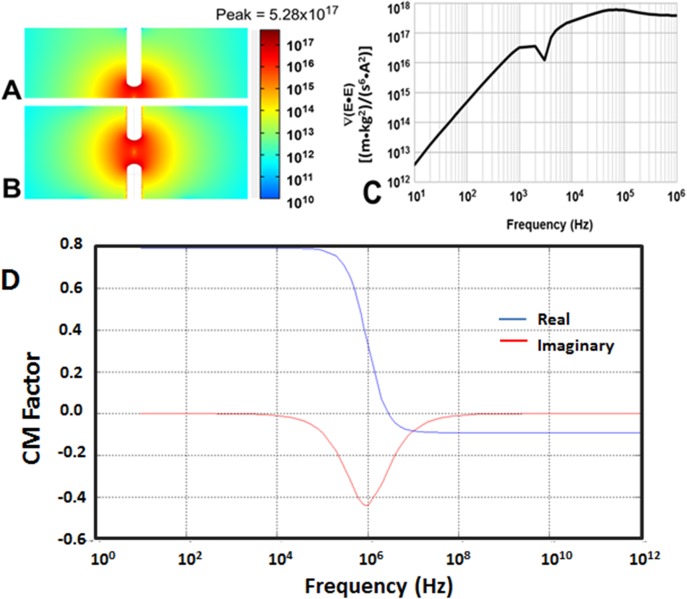

The findings from numerical modelling are shown in Figure 5. ∇(E • E) was computed for an applied signal of 400 Vpp at 300 kHz. The top view and cross-section view of the slice plot of ∇(E • E) are shown in Figures 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. A PDMS structure molded the shape of the microfluidic channel. The analysis accounted for the DI water medium filling the entire channel. A thin glass slide passivation layer separated the medium from the activation layer of electrodes. Finally, metal electrodes beneath the passivation layer were used to activate the device model. The electrical properties of the layers considered are shown in Table I.

FIG. 5.

COMSOL simulations of electric fields in 3D πDEP devices. (a) Side view of ∇(E•E) profile at 400 Vpp and 300 kHz. (b) Top view of ∇(E•E) profile at 400 Vpp and 300 kHz. (c) Maximum values of ∇(E•E) as a function of frequency. (d) Simulated values of the real and imaginary Clausius-Massotti factor.

TABLE I.

Electrical properties of material layers used in the modeling analysis.

| Material | Electrical properties | |

|---|---|---|

| DI water | Relative permittivity, εm | 80 |

| Electrical conductivity, σm | 0.0008 S/m | |

| Glass | Density | 965 kg/m3 |

| Electrical conductivity, σ | 1.25 × 10−9 S/m | |

| Metal electrodes | Reference resistivity, ρ | 1.72 × 10−8 Ω m |

| Electrical conductivity, σ | 5.998 × 107 S/m | |

| S. aureus | Relative permittivity, εp | 60 |

| Electrical conductivity, σp | 0.01 S/m | |

The frequency dependent model was activated using an applied electrical signal and then a parametric sweep was conducted over a range of frequencies from 10 Hz to 1 MHz to test the device model. The peak gradient was found to be . This is two orders of magnitude greater than the peak gradients using the exact same input signal in our previous iDEP devices which only varied in two dimensions.20 To obtain an estimation of the Clausius-Massotti factor (fCM), the electrical parameters of S. aureus bacteria and the surrounding DI water medium shown in Table I were used.12 Using Eqs. (2) and (3), real and imaginary values of fCM were estimated using Matlab R2014a, as shown in Figure 5(d). Notably, the complex nature of bacteria cells, the unique oval shape, and the single shell model would further influence fCM. The generated DEP force experienced by a bacteria in the 3D πDEP is a function of the simulated results of ∇(E • E) and fCM.

As shown in Eq. (1), the DEP force acting on a particle is directly proportional to ∇(E•E). Therefore, because of the higher ∇(E • E) component, a much larger DEP force is generated by 3D πDEP devices for the same applied signal in comparison to 2D iDEP devices. Additionally, it is vital to note that electric field gradients in 3D πDEP devices vary in all three dimensions unlike gradients in 2D πDEP devices that only vary in two dimensions. The higher electric field gradients in 3D πDEP devices further account for stronger DEP forces experienced by particles.

The frequency response of the 3D πDEP device is shown in Figure 5(c). Because the applied signal is capacitively coupled through a thin 100 μm glass slide that seals the microfluidic cartridge, the frequency response is analogous to a high pass filter with the attenuation increasing as the frequency is lowered. A dip in ∇(E • E) is observed at 2 kHz and this is attributed to the device operating near the resonant frequency of the circuit. There are several impedances both in series and in parallel to the active area of the device for which ∇(E • E) is calculated. This phenomenon is especially enhanced in capacitively coupled systems. Notably, the magnitude of the electric field gradient does not dip below until the frequency is ∼150 Hz. This model therefore predicts the ability of 3D πDEP devices to operate over a wide frequency range, including very low frequencies.

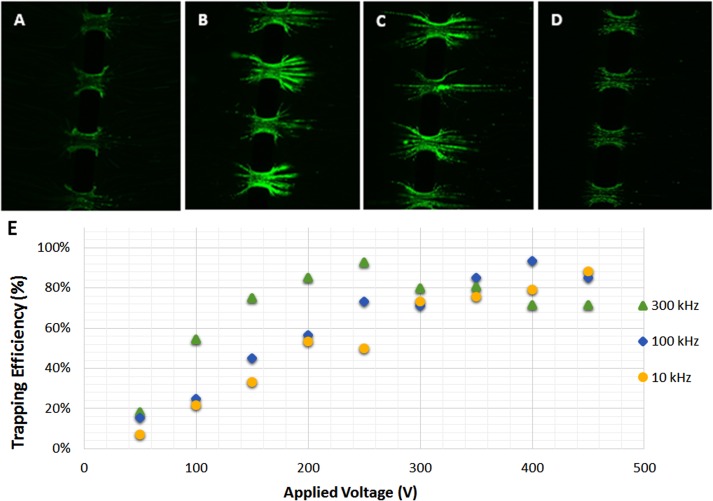

B. Frequency response

DEP trapping experiments with S. aureus were conducted and a signal amplitude of 200 Vpp was maintained at an applied flow rate of 100 μl/h. The experimental performance of the 3D πDEP device as a function of the applied frequency is shown in Figure 6. Under these conditions, DEP trapping with 80%–100% capture efficiency was observed over a wide range of frequencies, from 600 Hz to 400 kHz for S. aureus. The reported results further support predictions from the numerical model. Because the strong DEP forces generated by the 3D πDEP are greater than over a broad frequency range, the microfluidic system is highly likely to achieve trapping over a wide frequency range. However, due to the limited bandwidth of the power amplifier used in our experiments, a decrease in capture efficiency is observed at higher frequencies.

FIG. 6.

Images are of live S. aureus trapping (a) 300 Hz signal, (b) 3 kHz signal, (c) 30 kHz signal, (d) 300 kHz, and (e) trapping as a function of frequency (n = 3).

The results showed that even at the lowest frequency tested (50 Hz), some bacteria were successfully trapped. At lower frequencies (20–100 kHz), it was observed that the trapped bacteria tend to form extra elongated chains, as shown in Figures 6 and 7. This behaviour of bioparticles forming pearl chains when trapped in DEP devices has been previously reported.29 At high frequencies (<200 kHz), however, trapping of bacteria was concentrated at the microposts with shorter pearl chains. This is attributed to stronger pDEP forces at high frequencies than at low frequencies, and these therefore pull the entire pearl chain to the 3D insulating microposts, where the electric field gradient is greatest. A recorded video showing elongated chains of trapped bacteria at a low applied frequency of 100 kHz, and the bacteria being pulled in, constricted, and compacted at the microposts when the applied frequency is increased from 100 kHz to 300 kHz is shown.30 When the applied voltage signal was turned off, all previously trapped bacteria were released, thus, trapping was found to be reversible.

FIG. 7.

Low voltage operation of the 3D DEP device (n = 3). (a) Poor trapping at 200 Vpp and 800 Hz applied frequency. (b) Long pearl chains at low frequency of 200 Vpp and 10 kHz. (c) Trapping in long chains for 200 Vpp and 100 kHz applied signal. (d) Trapping concentrated at the microposts 300 kHz. (e) Trapping efficiency against varied applied signal voltages.

C. Low voltage operation

With the frequency held constant, voltage sweeps were conducted over an experimentally determined device bandwidth. The flow rate was held constant at 100 μl/h, while the applied signal amplitude was gradually incremented from 0 to 450 Vpp. Variations in trapping efficiency with changing amplitude were recorded, and the results are shown in Figure 7. Results showed that minimum trapping voltage rapidly decreased with increasing frequency. At 300 kHz, we observed trapping over 80% at voltages as low as 100 Vpp and the trapping gradually increased with increasing applied voltage. At 10 kHz, very low trapping efficiencies were recorded at applied signals below 300 Vpp. Notably, we observed some trapping at the lowest applied voltage of 50 Vpp for all frequencies investigated, as shown in Figure 7. These results support the theory that at higher frequencies the particles experience stronger DEP force. Furthermore, this study demonstrates the capability to operate at lower applied voltages. The reported applied signals in 3D πDEP devices are significantly low compared to traditional iDEP device, which typically require high voltages (∼1000 Vpp) to operate.10,11 However; for iDEP devices utilizing 3D constrictions, lower operating voltages have been reported by researchers. Braff et al. reported some trapping of bacteria strains using a traditional iDEP device with 3D microstructures and electrodes in direct contact with the solution.15,31 In our previous work with 3D iDEP devices fabricated on a silicon substrate, we reported 50% selective trapping of 1 μm and 2 μm beads in a high conductivity 20.0 mS/m solution at 100 VDC applied signal.16 In this study, however, significant trapping of S. aureus bacteria at low signal amplitudes with electrodes capacitively coupled through a glass slide has been demonstrated. This 3D πDEP device achieves low voltage trapping while maintaining high trapping efficiency over a wide range of frequencies.

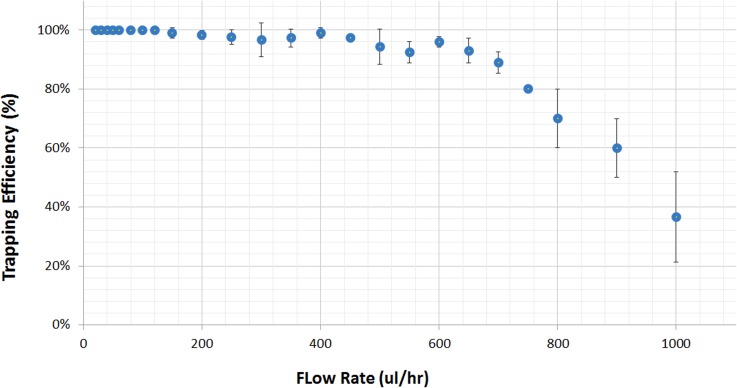

D. Flow rate analysis

Analysis to determine maximum throughput of the 3D πDEP device was conducted. The applied signal was held constant at 200 Vpp and 300 kHz, while the medium flow rate was varied from 20 μl/h to 1000 μl/h. Results showing capture efficiency as a function of fluid flow rate are shown in Figure 8. During the flow sweeps, it was observed that trapping improved with reducing fluid flow rates, and this behaviour is further supported by Eq. (4). As shown in Figure 8, the device obtained 100% capture efficiency for flow rates up to 350 μl/h and trapping efficiency over 90% for flow rates up to 700 μl/h. The device capture efficiency decreased steadily from 700 μl/h to 1000 μl/h but remained above 50%. At these high flow rates, over 700 μl/h, the drag force acting on the particles was significant to pull pearl chains of previously trapped S. aureus off the 3D microposts.

FIG. 8.

Observed DEP trapping of S. aureus by a 3D πDEP device at an applied electrical signal of 200 Vpp and 300 kHz. Capture efficiency as function of medium flow rate (n = 3).

Notably, the 3D πDEP technology proposed in this work uses 3D insulating features. The constriction regions near the insulating posts are shallow, as shown in the SEM image of Figures 4(c) and 4(d). This ultimately compromises device throughput as opposed to 2D iDEP and eDEP devices that have been reported to operate at high flow rates.32,33 The 3D πDEP throughput could be readily enhanced by aligning channels in parallel or increasing the channel depth and width dimensions. Consequently, the trapping efficiency deteriorated from here onwards. Therefore, for experiments with an emphasis on high trapping efficiency, flow rates under 700 μl/h are preferable whereas in cases where high throughput is of greater importance, the device can operate above 700 μl/h.

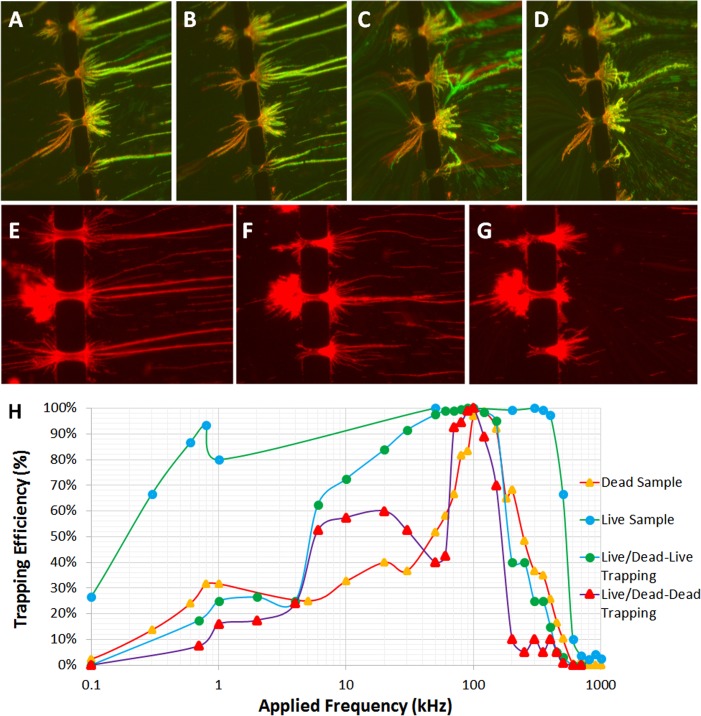

E. Separation of particles

Biological samples containing live only, dead only, and a mixture of live/dead S. aureus bacteria were analyzed using the 3D πDEP device. A solution containing both live and dead S. aureus was used to investigate the ability of 3D πDEP to selectively concentrate closely related biological samples. The S. aureus dead sample was prepared by boiling a live bacteria sample in a water-bath at 80 °C for 20 min. The sample was allowed to cool for 5 min in a beaker of cold water and then stained red with a live/dead viability Kit (Backlit Invitrogen). This was then added to a similarly stained green live bacteria sample. Results from the mixed live/dead sample showed that we could separate live bacteria from dead bacteria at frequencies ranging from 30 to 60 kHz. Figures 9(a) and 9(b) show that with an applied signal of 400 Vpp and 30 kHz, 98% of the green stained live bacteria are trapped at the 3D microposts, while the red stained bacteria can be seen escaping on the left side of the microposts.

FIG. 9.

Pointedly, we observe that with increased trapping of live bacteria, the electric field gradients in the channel rapidly increase especially when long pearl chains of bacteria are trapped at the microposts. This increases device capability to trap both live and dead bacteria. Dead bacteria start to accumulate on the previously trapped live bacteria pearl chains. However, when the applied signal is removed, the green bacteria that were strongly immobilized by the DEP force are immediately released, as shown in Figure 9(c). Dead bacteria previously trapped on the long pearl chains of live bacteria are released a few seconds later, as shown in Figure 9(d) (Multimedia view).30 This affirms our understanding that the live bacteria were selectively trapped at the frequency ranges 30–60 kHz, while most of the dead bacteria escaped. We observed 100% capture efficiency when trapping a combination of live and dead S. aureus over a 90–100 kHz frequency range, as shown in Figure 9(h). Trapping deteriorated beyond 400 kHz due to bandwidth limitations of the amplifier. It should be noted, however, that dead bacteria had a tendency to foul the surface and stick to the microposts even after the applied signal was removed, as seen in Figure 9(d). Fouled bacteria can be removed by increasing the flow rate prior to the next run.

As seen previously with live S. aureus samples, Figures 9(e)–9(g) show trapping of dead bacteria with extra-long pearl chains formed at lower frequencies, 10–100 kHz. At higher frequencies (<250 kHz), the trapping was concentrated at the microposts due to the particle experiencing a stronger DEP force. To fine tune selectivity of the device, a frequency sweep for a purely dead S. aureus sample was obtained and interposed this with results from a purely live sample, as shown in Figure 9(h). The live sample (Green) consisted of only live bacteria. Results showed a trapping efficiency over 80% for frequencies ranging from 600 Hz to 400 kHz and maximum trapping efficiency starting at 60 kHz. The more bacteria are trapped in elongated pearls, the more the electrical field gradient is enhanced within the channel further increasing the trapping efficiency. Notably, beyond 400 kHz, the power amplifier starts to attenuate causing a sudden drop in the trapping efficiency. The same is true for dead sample containing dead bacteria. However, we can easily observe that increase in the trapping efficiency of dead bacteria happens closer to 100 kHz, and there is distinct efficiency between live and dead sample when it comes to frequencies between 1 and 70 kHz.

The live/dead sample consisted of a mixture of live and dead bacteria. Using ImageJ, we analyzed the trapping efficiency of live (blue) and dead (purple) bacteria in the mixed sample population. It should be noted that trapping can affect the local electric field gradient, and hence, the trapping efficiency observed for the dead bacteria in the mixed population can be influenced by the trapping of live bacteria that can happen at lower frequencies. Nevertheless, we can see a more distinct separation between the live and dead bacteria at frequencies close to 60 kHz, while at frequencies around 100 kHz, the trapping efficiency of the entire sample is close to 100%. Again, due to limitations in the power amplifier, we could not conclude if the chip is capable of efficiently separating the live and dead bacteria at higher frequencies.

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have introduced the first reported 3D πDEP device capable of achieving high capture efficiencies and separation of biological particles at low voltages and have showcased its performance through numerical models and experiments. 3D πDEP combines the benefits of iDEP, eDEP, and microstructures fabricated in three dimensions. It is an advancement of our previously reported 2D iDEP and an alternative to our 3D iDEP device.17,20 As demonstrated in our results, 3D structures generate stronger DEP forces in comparison to 2D microstructures in iDEP devices, and the passivated electrodes are reusable. The stronger electric field gradient generated is further supported by the theory presented earlier in Eq. (1) showing that the FDEP is a function of the electric field gradient ∇(E • E). 3D insulating structures increase this component and ultimately generate stronger DEP forces. As a result of stronger electric field gradients, the operating bandwidth of the device was greatly improved. Exploiting this wide operating bandwidth and the frequency dependent response of biological particles in a DEP device, we can obtain finer tuning when manipulating closely related samples. Consequently, stronger DEP forces allowed for trapping at lower applied voltages thereby minimizing complications arising from joule heating. Electrodes located within the vicinity of the 3D microstructures reduce path travelled by current, when the applied signal is turned and ultimately minimize heat buildup in the entire microfluidic channel. Heat buildup in the microfluidic channel can result in device failure24 and potentially reduce sample viability in biological applications. Therefore, 3D πDEP devices can be operated for longer durations with minimal temperature effects on the biological sample. Additionally, by capacitively coupling through an insulating layer, the electrodes are never in direct contact with the solution thus avoiding sample contamination and gas evolution. These reported advances in performance are obtained while maintaining a simple, low cost, single etch, single mask, polymer mold fabrication. The device ability to operate at lower applied voltages minimizes chances of cell death due to electroporation. To further curb this problem, the applied signal was turned on in short bursts during trapping and turned off after. The channel design of 3D insulating microstructures improves the electric field gradients, ultimately increasing the DEP force acting on bioparticles. Capture efficiency of 100% was achieved for an applied voltage of 200 Vpp over a wide frequency bandwidth ranging from 600 Hz to 400 kHz. Because trapping of microparticles is concentrated at the microposts, the device throughput can be improved by widening the microchannel. To characterize different biological samples, the applied signal amplitude and frequency as well as a combination of AC and DC signals can be manipulated to selectively trap bioparticles. Moreover, the 3D πDEP devices can be customized by changing the electrode and 3D insulating structures to achieve high selectivity of closely related bioparticles. This 3D πDEP device offers the capability for low cost disposable testing of water samples in the field. Additionally, the low frequency operation of the device allows for exploitation of a wider frequency range on the DEP spectrum when investigating different biological samples. A summary of the advantages and disadvantages of 2D iDEP and 3D πDEP microfluidic designs are shown in Table II.

TABLE II.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of 2D iDEP, 2D OπDEP, and 3D πDEP chip designs.

| DEP device | 2D iDEP | 3D πDEP |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | —Insulating structure design flexibility | —High electric field gradients generated |

| —Easy to mass produce | —3D flexibility in insulating structure design | |

| —No direct electrode contact with the sample | ||

| —Low cost mass production of polymer substrate | ||

| —Minimal heat buildup near insulating structures | ||

| —Flexibility in electrode shape design | ||

| —Large bandwidth | ||

| Disadvantages | —Large heat buildup near insulating structures | —High AC fields to capacitively couple through glass slide |

| —Electrodes in contact with solution | —3D fabrication required | |

| —Requires large DC voltages to operate |

The reported results showcase the promising potential of the 3D πDEP device as a low cost, high throughput, and highly efficient platform for biological sample analysis for applications ranging from pathogen manipulation to medical and therapeutic diagnostics. Furthermore, the passivated electrodes offer reusability and flexibility in electrode design.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported primarily by the National Science Foundation under Award Number ECCS - 1310090.

References

- 1.Pohl H. A., Dielectrophoresis-The Behavior of Neutral Matter in Nonuniform Electric Fields ( Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y.et al. , “ Differences in the AC electrodynamics of viable and non-viable yeast cells determined through combined dielectrophoresis and electrorotation studies,” Phys. Med. Biol. 37(7), 1499 (1992). 10.1088/0031-9155/37/7/003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou R., Wang P., and Chang H.-C., “ Bacteria capture, concentration and detection by alternating current dielectrophoresis and self-assembly of dispersed single-wall carbon nanotubes,” Electrophoresis 27(7), 1376–1385 (2006). 10.1002/elps.200500329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt T. P. and Westervelt R. M., “ Dielectrophoresis tweezers for single cell manipulation,” Biomed. Microdevices 8(3), 227–230 (2006). 10.1007/s10544-006-8170-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park S., Bassat D. B., and Yossifon G., “ Individually addressable multi-chamber electroporation platform with dielectrophoresis and alternating-current-electro-osmosis assisted cell positioning,” Biomicrofluidics 8(2), 024117 (2014). 10.1063/1.4873439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shim S.et al. , “ Antibody-independent isolation of circulating tumor cells by continuous-flow dielectrophoresis,” Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 011807 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C.et al. , “ Characterization of microfluidic shear-dependent epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunocapture and enrichment of pancreatic cancer cells from blood cells with dielectrophoresis,” Biomicrofluidics 8(4), 044107 (2014). 10.1063/1.4890466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shake T.et al. , “ Embedded passivated-electrode insulator-based dielectrophoresis (EπDEP),” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405(30), 9825–9833 (2013). 10.1007/s00216-013-7435-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alshareef M.et al. , “ Separation of tumor cells with dielectrophoresis-based microfluidic chip,” Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 011803 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davalos R.et al. , “ Performance impact of dynamic surface coatings on polymeric insulator-based dielectrophoretic particle separators,” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390(3), 847–855 (2008). 10.1007/s00216-007-1426-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-López J.et al. , “ Characterization of electrokinetic mobility of microparticles in order to improve dielectrophoretic concentration,” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394(1), 293–302 (2009). 10.1007/s00216-009-2626-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchis A.et al. , “ Dielectric characterization of bacterial cells using dielectrophoresis,” Bioelectromagnetics 28(5), 393–401 (2007). 10.1002/bem.20317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo J.et al. , “ Insulator-based dielectrophoresis of mitochondria,” Biomicrofluidics 8(2), 021801 (2014). 10.1063/1.4866852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C.-T., Weng C.-H., and Jen C.-P., “ Three-dimensional cellular focusing utilizing a combination of insulator-based and metallic dielectrophoresis,” Biomicrofluidics 5(4), 044101 (2011). 10.1063/1.3646757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braff W. A.et al. , “ Dielectrophoresis-based discrimination of bacteria at the strain level based on their surface properties,” PLoS ONE 8(10), e76751 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0076751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zellner P. and Agah M., “ Silicon insulator-based dielectrophoresis devices for minimized heating effects,” Electrophoresis 33(16), 2498–2507 (2012). 10.1002/elps.201100661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zellner P.et al. , “ 3D Insulator-based dielectrophoresis using DC-biased, AC electric fields for selective bacterial trapping,” Electrophoresis 36(2), 277–283 (2015). 10.1002/elps.201400236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kale A.et al. , “ Numerical modeling of Joule heating effects in insulator-based dielectrophoresis microdevices,” Electrophoresis 34(5), 674–683 (2013). 10.1002/elps.201200501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sridharan S.et al. , “ Joule heating effects on electroosmotic flow in insulator-based dielectrophoresis,” Electrophoresis 32(17), 2274–2281 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zellner P.et al. , “ Off-chip passivated-electrode, insulator-based dielectrophoresis (OπDEP),” Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405(21), 6657–6666 (2013). 10.1007/s00216-013-7123-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pohl H. A. and Schwar J. P., “ Factors affecting separations of suspensions in nonuniform electric fields,” J. Appl. Phys. 30(1), 69–73 (1959). 10.1063/1.1734977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pethig R., “ Review article—dielectrophoresis: Status of the theory, technology, and applications,” Biomicrofluidics 4(2), 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castellarnau M.et al. , “ Dielectrophoresis as a tool to characterize and differentiate isogenic mutants of Escherichia coli,” Biophys. J. 91(10), 3937–3945 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.088534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabounchi P., Huber D. E., Kanouff M. P., Harris A. E., and Simmons B. A., “ Joule heating effects on insulator-based dielectrophoresis,” paper presented at the 12th International Conferences on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences, San Diego, California, USA, 12–16 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabounchi P.et al. , “ Sample concentration and impedance detection on a microfluidic polymer chip,” Biomed. Microdevices 10(5), 661–670 (2008). 10.1007/s10544-008-9177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gantz K., Renaghan L., and Agah M., “ Development of a comprehensive model for RIE-lag-based three-dimensional microchannel fabrication,” J. Micromech. Microeng. 18(2), 025003 (2008). 10.1088/0960-1317/18/2/025003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosseini Y., Zellner P., and Agah M., “ A single-mask process for 3-D microstructure fabrication in PDMS,” J. Microelectromech. Syst. 22(2), 356–362 (2013). 10.1109/JMEMS.2012.2231402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zellner P.et al. , “ A fabrication technology for three-dimensional micro total analysis systems,” J. Micromech. Microeng. 20(4), 045013 (2010). 10.1088/0960-1317/20/4/045013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafiee H.et al. , “ Selective isolation of live/dead cells using contactless dielectrophoresis (cDEP),” Lab Chip 10(4), 438–445 (2010). 10.1039/b920590j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4913497E-BIOMGB-9-029501 for showing selective and targeted trapping of a live bacteria sample population.

- 31.Braff W. A., Pignier A., and Buie C. R., “ High sensitivity three-dimensional insulator–based dielectrophoresis,” Lab Chip 12(7), 1327–1331 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21212a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markx G. H., Dyda P. A., and Pethig R., “ Dielectrophoretic separation of bacteria using a conductivity gradient,” J. Biotechnol. 51(2), 175–180 (1996). 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01617-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y.et al. , “ Introducing dielectrophoresis as a new force field for field-flow fractionation,” Biophys. J. 73(2), 1118–1129 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78144-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4913497E-BIOMGB-9-029501 for showing selective and targeted trapping of a live bacteria sample population.