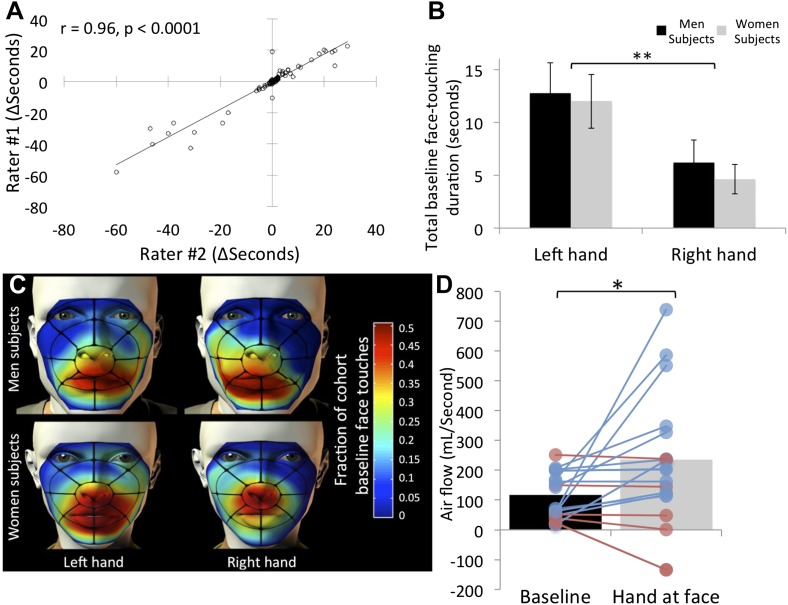

Figure 2. Humans often touch their own face and concurrently sniff.

(A) Agreement in scoring of 153 subjects across two independent raters. (B) Total face touching duration during the 1-min baseline. (C) Spatial distribution of face touching during the 1-min baseline. Grid reflects 17 facial regions. (D) Measure of nasal airflow during baseline vs the time when a hand was at the face. Subjects that increased flow in blue and subjects that decreased flow in red. Solid bars reflect the mean. Error bars in B are standard error. **p < 0.01. *p < 0.05.