Abstract

This study examines predictors, moderators, and treatment parameters associated with two key child outcomes in a recent clinical trial comparing the effects of a modular treatment that was applied by study clinicians in the community (COMM) or a clinic (CLINIC) for children with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD). Based on a literature review, moderator and predictor variables across child, parent, and family domains were examined in relation to changes in parental ratings of the severity of externalizing behavior problems or the number of ODD and CD symptoms endorsed on psychiatric interview at pretreatment, posttreatment, and 36-month posttreatment follow-up. In addition, associations between parameters of treatment (e.g., hours of child, parent, and parent–child treatment received, treatment completion, referral for additional services at discharge) and child outcomes were explored. Path models identified few moderators (e.g., level of child impairment, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis, level of family conflict) and several predictors (child trauma history, family income, parental employment, parental depression) of treatment response. Treatment response was also related to a few treatment parameters (e.g., hours of child and parent treatment received, treatment completion, referral for additional services at discharge). We discuss the implications of these findings for maximizing the benefits of modular treatment by optimizing or personalizing intervention approaches for children with behavior disorders.

Keywords: Treatment moderators, Predictors of outcome, Treatment of disruptive behavior disorders, Behavior disorders, Outcome studies, Clinical trials

Introduction

Child behavior problems (BP) or disruptive behavior disorders (DBD) characterized by oppositionality, disruptiveness, aggression, and rule-breaking behavior (American Psychiatric Association 2000) are the most common reason for referring children for mental health treatment (Tempel et al. in press). The efficacy of several interventions for children with BP or DBD has been demonstrated in both clinic and community settings (see Eyberg et al. 2008; Kazdin 2011). Clinic-based treatments include cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT; Kazdin et al. 1992; Nelson-Gray et al. 2006), parent management training (PMT; Martinez and Forgatch 2001), parent–child interaction training (Werba et al. 2006), family treatment (FT; McTaggart and Sanders 2007) and multicomponent treatment (Webster-Stratton et al. 2004). Likewise, community-based treatments include Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler et al. 2002), Coping Power (Lochman and Wells 2003), and the parent COPE program (Lipman et al. 2006).

These clinical and empirical developments notwithstanding, a significant minority of cases show limited or no initial response or show an initial response that is not maintained. For example, meta-analyses of treatments conducted in research clinics report modest but variable improvements in child aggression or other conduct problems (Mean effect sizes [ES] = 0.40–49; see McCart et al. 2006), and overall behavioral outcomes (M ES = 0.42; see Lundahl et al. 2006). These findings indicate that some children may benefit more than others from the same evidence-based treatment (EBT). Therefore, it is important to explore predictors and moderators of effectiveness to better understand for whom treatments may be more or less effective.

It is useful to first differentiate predictors and moderators of treatment response. In treatment studies, moderator variables specify the conditions under which or individuals for whom a treatment condition may be more or less effective (Baron and Kenny 1986; Kraemer et al. 2002) whereas predictor variables are not differentially linked with treatment response depending on treatment group assignment, although they are related to the outcome (Shelleby and Shaw 2013). The important difference between predictors and moderators is illustrated by the following example. To explore the influence of income on treatment response, examining this relationship in one treatment group only could demonstrate if income served as a predictor by affecting the outcome among those in the treatment group. However, by comparing to a different condition, researchers are better able to understand whether a variable is differentially associated with treatment response across conditions. Examining the effect of the interaction between treatment and income on outcomes provides greater information regarding the influence of this risk variable across different treatment groups (e.g., if those with lower income only improved in one group and not another). A non-significant interaction would demonstrate that effects did not vary by income. Level of income may still be a predictor if there were main effects regardless of group (e.g., in both groups, those with lower compared to higher incomes had worse outcomes). Testing an interaction and finding a non-significant moderating effect but significant predictor effect provides greater information than a predictor finding involving only one condition. Comparing to a different group can specify that income did not differentially affect outcomes across groups.

We focus on three domains of variables that have been explored as predictors and moderators of treatment response in previous research on BP treatment: child level variables (e.g., child severity, comorbid disorders), family level variables (e.g., parental psychopathology, family conflict), and sociodemographic level variables (e.g., family income, parental education). With regard to child level variables, researchers have frequently examined how baseline level of child problem behavior influences treatment response, which is very important given findings that children with the most elevated rates of BP at young ages are at greater risk for long-term persistence of BP and exacerbation of problematic behaviors (Shelleby and Shaw 2013; Aguilar et al. 2000; Campbell et al. 2000). Because treatment for children with the highest initial levels of BP may prevent longer-term costs, it is of great importance to understand potential differential effectiveness of treatments for such children. In addition, differences in the family context in which treatments are disseminated may be associated with differential treatment effects. Several sociodemographic and family contextual risk factors (e.g., family income, employment status, maternal depression, family conflict) are also of critical importance in understanding treatment effects. Low SES and maternal depression have been associated with compromised family processes and BP (e.g., Lovejoy et al. 2000; McLeod and Shanahan 1993), so therefore they may reduce treatment effects. However, on the other hand, a treatment could potentially interrupt the negative association between stressors and BP, which could enhance treatment effects. Therefore, it is important to explore the influence of these variables on treatment response.

The identification of general predictors of outcome may help to refine existing treatments or enhance their effectiveness. In a meta-analytic review of the variables related to outcomes following parenting interventions, Reyno and McGrath (2006) identified moderate standardized effect sizes for several predictors of treatment response (i.e., low parental education/occupation, severe child behavior problems, maternal psychopathology). Only low family income resulted in a large standardized effect size. In general, individual studies have examined characteristics from various domains (e.g., child, parent, family) that predict treatment response (i.e., degree of change in key problems) or outcome (i.e., clinical status after treatment). Among child factors, clinical comorbidity has been found predictive of greater response, albeit poorer posttreatment clinical status or outcome, in several trials (Beauchaine et al. 2005; Kazdin and Whitley 2006; Lavigne et al. 2008a; van den Hoofdakker et al. 2010), with some exceptions (Reid et al. 2004). In a study of young children with ODD treated in pediatric primary care settings (Lavigne et al. 2008b), several child variables showed the same pattern of results predicting greater response (e.g., child internalizing problems, functional impairment, difficult temperament), which is consistent with another study from primary care which showed that child health improvement was predicted by the severity of the child’s depression and anxiety, and level of family conflict (Kolko et al. 2011a). In contrast, family background characteristics (e.g., young child age, gender, marital status, low income) as well as parental factors (e.g., parental dysfunction, maternal depression) examined as predictors have varied in both magnitude and direction of response or outcome across studies (Lundahl et al. 2006). In general, these results highlight several complex and discrepant relations between family and demographic variables as predictors and treatment response or outcome (Reyno and McGrath 2006).

Fewer studies have examined treatment moderators despite the need to identify those key characteristics that differentially affect treatment response in alternative intervention conditions. Similar to predictor outcomes, level of child problem behavior at baseline has consistently been shown to be associated with greater intervention effectiveness. For example, in a meta-analysis of parenting interventions that explored moderation, Lundahl et al. (2006) found greater effects for children with higher baseline behavior problems. In addition, a number of individual empirical studies exploring moderating effects have found that the more problematic a child’s behavior was rated at baseline, the greater change in problem behavior occurred through intervention (Chamberlain et al. 2008; Reid et al. 2004; Shaw et al. 2006; Tein et al. 2004). However, a few other studies have found nonsignificant moderation by baseline child behavior (Gardner et al. 2010; Lavigne et al. 2008b), possibly due to the fact that these samples included children who were all rated within the clinical range on baseline BP (Shelleby and Shaw 2013). Although these findings are relatively robust, there is a dearth of research examining baseline child variables as moderators across alternative active treatment conditions, rather than treatment versus control. Here, we examine whether child level variables interact with active treatment condition (e.g., CLINIC or COMM) to moderate response to treatment or if child level variables serve as non-specific predictors of treatment response, if moderation is not supported.

Previous research examining differential effects by family level variables, such as parent psychopathology and conflict, are more varied. Some studies report significant moderation with greater effects for those experiencing greater stressors when comparing a treatment to a control group. For example, Gardner et al. (2010) and Shaw et al. (2006) found that children of mothers with greater depression evidenced greater benefit from intervention for BP compared to controls. Similarly, intervention effects on child BP have been found to be greater for those at higher baseline cumulative risk (including measures of CP, parental conflict, negative life events, maternal distress, reduced father contact, and financial hardship; Zhou et al. 2008). In contrast, other studies examining family level risks such as maternal depression, other measures of psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, substance use), or indices of well-being or impairment found non-significant moderating effects when comparing treatment to control groups (Gardner et al. 2009; Lavigne et al. 2008b; McTaggart and Sanders 2007; Stolk et al. 2008). Given that the current study involves comparing across the same treatment in different settings, we hypothesize that greater family stressors will moderate response such that contextual characteristics (e.g., parent dysfunction, family conflict) will have more of an adverse impact on outcome in the community than in the clinic.

Similar to the moderator literature on family stressors, results from studies examining differential effects by sociodemographic factors are mixed. With regard to meta-analytic results, Lundahl et al. (2006) found reduced effects for low SES and single parent families involved in parenting interventions. Gardner et al. (2009) found poorer BP outcomes for children of single (d = 0.04) compared to partnered parents (d = 0.53), but on the other hand, this study found greater decreases in BP for children of mothers with lower education (high education, d = 0.15–0.18; low education, d = 0.68–1.17). However, other studies exploring measures of parental education as a moderator have reported no differential effects (Kling et al. 2010; Lavigne et al. 2008b, McTaggart and Sanders 2007; Stolk et al. 2008). Similarly, studies investigating parental age and income/SES have found non-significant moderation by these variables (Gardner et al. 2009, 2010; Kling et al. 2010; Lavigne et al. 2008b; McGilloway et al. 2012; McTaggart and Sanders 2007). Although most of these results suggest that sociodemographic variables do not moderate effects, importantly, most of these studies involved comparing an intervention versus a no-treatment or wait-list control group. Given our interest in comparing the same treatment across different settings, we expect that some sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., low family income, parent employment, parent education) will have more of an adverse impact on outcome in the community than in the clinic.

Beyond identifying pre-intervention variables associated with treatment response as either predictors or moderators, it is also important to identify different elements of the treatment process itself, which we refer to as treatment parameters, that may influence response. Further examination of the role of treatment parameters and dose–response relationships in child outcome studies is also needed, especially since few studies have either examined or found evidence for them (Bickman et al. 2002). Emerging evidence from recent trials highlights some relationships between key treatment parameters and positive response or outcome (e.g., primary content, fidelity; Kelley et al. 2010). For example, improved outcomes have been reported for families of BP children who received at least seven sessions of a behavioral parent training program (Lavigne et al. (2008b) or treatment resistant depressed adolescents who received at least 9 sessions of problem solving and social skills training (Kennard et al. 2009). Further, evidence suggests the importance of child and parent involvement in treatment (Kaminski et al. 2008), consistent with the results of some recent studies (Hagen et al. 2011; Webster-Stratton and Reid 2011). In one study, duration of child exposure to CBT was related to greater improvement in child health, but other treatment parameters (e.g., parent duration, treatment completion) were unrelated to outcome (see Kolko et al. 2010). Thus, treatment parameters reflecting dose or intensity and content may relate to improved response, suggesting that an evaluation of similar variables may promote the efficiency of novel treatments designed to address children’s BP.

The evaluation of treatment moderators, predictors, and key treatment parameters has been encouraged to identify characteristics that differentially affect response to alternative interventions, which may optimize treatment selection for a given patient (La Greca et al. 2009). Studies that address these topics using variables from several domains (e.g., demographics, child, parent, and family functioning, treatment dose) may promote this more personalized approach to intervention for children with BP, which reflects a key treatment priority in the National Institute of Mental Health’s recent Strategic Plan (NIMH 2008), especially strategic objective #3 which seeks to develop more effective interventions that incorporate the diverse needs and circumstances of people with mental disorders. This objective emphasizes both patient preference and personalization of care based on an understanding of each individual’s unique characteristics to optimize outcome. Such an approach extends the availability of information that can tailor an intervention to a patient’s clinical needs.

With the large scale dissemination of numerous EBTs, it is becoming increasingly necessary to know for whom they work best so that treatment applications can be more carefully matched to enhance participation and outcome. For example, the identification of treatment moderators that highlight the amenability of subpopulations may be important for the delivery of interventions in diverse settings, such as the child’s ecology/community or in an outpatient clinical setting. Certain parent or family characteristics may have a more adverse influence (associated with less clinical improvement) in community (vs. clinic) settings where clinicians attempt to directly target these diverse contexts (Loeber et al. 1998; Swenson et al. 2010), such as family stress, dysfunction, or conflict. In community settings, such characteristics may get in the way of implementation. Thus, it is important to learn if contextual characteristics across these domains differently affect outcomes of interventions delivered in the child’s ecology (community) or the more routine outpatient setting (clinic). Alternatively, predictors of treatment outcome may identify key variables that may need additional targeting to enhance the clinical yield of interventions conducted in either setting.

This study seeks to extend this literature by examining moderators and predictors of outcome for a modular treatment protocol developed for early-onset ODD or CD applied by trained research clinicians either in community settings (COMM) or a separate research clinic setting (CLINIC) based on a recent clinical trial (Kolko et al. 2009). The protocols included content administered on an individual (parent, child) and parent–child basis. The comparison of parallel protocols in different contexts allows for a unique evaluation of the role of potential moderators across diverse child, parent, and family factors, many of which have been examined separately in individual studies (see McCart et al. 2006). The study also examines outcomes on standardized rating scales and diagnostic interviews. Based on the existing treatment outcome literature, we test the following hypotheses: (1) child comorbidity, more so than parental or family dysfunction, will predict overall outcome across all cases, (2) contextual characteristics (e.g., parental dysfunction, family conflict) will have more of adverse impact on outcome in the community than in the clinic, and (3) exposure to a greater dose of parent and child treatment will enhance outcome. The study benefits from the inclusion of a long follow-up interval (3-years) with a DBD population, clinically referred boys and girls, and multivariate models (Kazdin and Whitley 2006).

Method

Participants

Participants included 144 clinically referred children (ages 6–11) diagnosed with ODD (n = 115) or CD (n = 29) recruited through program sites affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Children were randomly assigned to one of two modular treatment protocols administered either in the community (COMM; n = 72) or an outpatient research clinic (CLINIC; n = 72). Details of all inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Kolko et al. (2009). The average child age is 8.8 years, most (85 %) children were male, and about half (53 %) were African-American. Three-quarters of the sample had comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Mean socioeconomic status (SES) reflected a low to modest level of income (Hollingshead and Redlich 1958). The COMM and CLINIC conditions did not differ significantly on any background variables (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and frequencies for all baseline predictor and moderator variables, and treatment parameters, in the modular clinic and community treatment conditions

| Clinic

|

Community

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | |

| Variable | ||||||||

| Total income | $33,340 | $31,538 | $37,586 | $28,501 | ||||

| Parental employment | 53 | 76 % | 51 | 74 % | ||||

| Parental education (at least some college) | 45 | 64 % | 48 | 70 % | ||||

| Parental depression (BDI) | 9.15 | 7.74 | 7.65 | 6.93 | ||||

| Family conflict | 2.51 | 1.65 | 2.91 | 1.74 | ||||

| Child ADHD diagnosis | 54 | 77 % | 52 | 75 % | ||||

| Child impairment | 21.24 | 7.29 | 21.95 | 8.42 | ||||

| Teacher report of child aggression | 25.90 | 13.18 | 25.33 | 13.87 | ||||

| Child interpersonal trauma history | 42 | 60 % | 38 | 55 % | ||||

| Treatment parameters | ||||||||

| Hours of child cognitive behavioral therapy | 7.40 | 4.00 | 11.90 | 4.50 | ||||

| Hours of parent management training | 7.60 | 4.60 | 12.70 | 4.70 | ||||

| Hours of parent–child treatment | 4.30 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 2.50 | ||||

| Cases completed treatment | 53 | 75.7 | 67 | 97.1** | ||||

| Case referred at discharge for other services | 43 | 61.4 | 54 | 78.3* | ||||

p <0.05;

p <0.01

Assessment Procedures

The assessment battery incorporated several informants, methods, and measures, and was administered at pretreatment, posttreatment (about 6 months after pretreatment), and four follow-ups (6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-months posttreatment). The current study utilizes data collected at the pretreatment, posttreatment, and 36-month follow-up. All ratings scales were administered by a trained, BA-level research associate. Diagnostic interviews were conducted by a trained, master’s-level clinician. Child and parent informants were compensated for all assessments.

Child Behavior Outcomes: Rating Scale and Diagnostic Interview

Several of the outcome measures reported in the initial outcome study were highly intercorrelated (Kolko et al. 2009). Based on this level of overlap, two separate measures were selected for outcome analysis in this study given their different informants, commonality, clinical significance, and good psychometrics, namely, parent ratings of the severity of externalizing behavior problems and the number of ODD and CD symptoms endorsed based on diagnostic interview administered by a clinician. The alphas and descriptive statistics for these measures collected at pretreatment from the two treatment groups and the Healthy Control group were acceptable and are found in the initial outcome study (Kolko et al. 2009). These measures were modestly correlated at time 1 (r = 0.53).

Severity of Externalizing Behavior Problems

The first outcome measure reflected the severity of the child’s externalizing behavior problems within the past 6 months based on the caregiver-completed Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1991). This outcome has been reported in most of the treatment trials for behavior problem children or youth, and showed significant improvements in our initial treatment trial with DBD children. To avoid potential problems with interpretation of T-scores, we report herein the raw score for this scale.

Number of Disruptive Behavior Disorder Symptoms

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children for DSM-IV—Present and Lifetime (K-SADS; Kaufman et al. 1996; v. 10/1/96) was administered to evaluate current child psychiatric disorders, especially, ADHD (k = 0.83), ODD (k = 0.79), and CD (k = 0.74). Caregivers and children were interviewed separately and then together to clarify any discrepancies. For this study, we report an aggregate representing the total number of threshold symptoms endorsed for ODD and CD, in order to capture the overall severity of DBD symptoms. At pretreatment assessment, the correlation between these two child behavior outcome variables was modest, r = 0.50, p <0.001.

Moderator and Predictor Variables, and Treatment Parameters

Child Characteristics

Child Impairment

To assess overall level of child impairment, parents completed the 13-item Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS; Bird et al. 1993). Items rated on 0–4-pt scales were aggregated in four areas of functioning (e.g., family, peer, work, school) to form an overall score. Sample items include the extent to which a child has a problem with: getting into trouble, getting along with parents, and feeling unhappy. The CIS has good internal consistency, reliability, and validity in clinic samples. The alpha for the current sample was 0.71.

Child Aggression

Children’s teachers completed the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach 1991). The current study utilizes the teacher-reported aggression subscale, which includes 20 items tapping aggressive behavior. Sample items include: argues a lot, physically attacks people, cruelty, bullying or meanness to others. The TRF has good internal consistency, reliability, and validity in clinic samples. The alpha for the current sample was 0.95.

Child Interpersonal Trauma History

The children were administered four items from the Trauma Events Screening Inventory (TESI; Ford et al. 1999) to screen for exposure to trauma involving physical or sexual violence (i.e., witnessing violence at home, being physically injured/abused). These items were selected because ODD has been associated with increased victimization experiences (e.g., abuse), but not with non-victimization experiences (e.g., illnesses), and victimization has been related to aggression (Kolko et al. 2011b), so it may be relevant to DBD status. We report the presence/absence of interpersonal trauma exposure on any of these items.

Child ADHD Diagnosis

As described previously, primary caretakers and their children participated in a diagnostic interview using the K-SADS. A dichotomous variable for child’s diagnosis of ADHD at the pretreatment assessment was created based on the K-SADS parent and child interviews. Inter-rater reliability was high (k = 0.83).

Family Characteristics

Parental Depression

Caregivers completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al. 1988), a widely used measure of depressive symptoms utilized with both psychiatric and normal populations. Respondents rate the intensity of 21 depressive symptoms on a 0 (no symptomatology) to 3 (severe symptomatology) scale, and a score is derived by summing these ratings. Reliability and external validity of the BDI are high (Beck et al. 1988). The alpha for the current sample was 0.88.

Family Conflict

We administered to caregivers two family relationship index scales (conflict, cohesion) from the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos et al. 1974) which are issues among families of children with DBDs (see Loeber et al. 1998). Each item is rated as true/false and is aggregated to form a factor score. For the current study, we only utilize the conflict scale. The alpha for the current sample is 0.52.

Socioemographic Characteristics

A demographics questionnaire was completed by caregivers. In the current sample at pretreatment, mean household income was $35,431 (standard deviation = $30,044), 72 % of caregivers reported being employed, and 33 % of caregivers reported having at least graduated from high school, with 61 % having some college or more.

Treatment Parameters

Hours of Primary Treatment Components

The clinician completed a Services Provided Log to document details of each treatment contact (e.g., attendance, duration, procedures used). We report herein the “dose” or hours of the three primary treatment components used with all families (PMT, child CBT, parent–child sessions), which parallels variables from the service records used in similar studies (Kolko et al. 2011a).

Treatment Completion and Referral for Additional Services

The Treatment Termination Form (TTF) was completed by clinicians to document impressions of the course and outcome of the case at post-treatment assessment. We report the final status of the case in terms of whether they completed treatment (i.e., case received at least 15 h of direct services) or were referred for additional services (i.e., any outside referral).

Community (COMM) and Clinic (CLINIC) Modular Treatment Conditions

Overview and Setting Variations

Staff members were assigned to one condition only and initial assignments were done randomly. Therapists in COMM and CLINIC applied the same primary content, but the two conditions differed in the context (site) where the services were conducted. In COMM, services were provided in the child’s ecology (e.g., home, school, community), whereas services in CLINIC were provided in the outpatient office. COMM was coded as “0” and CLINIC as “1”.

Treatment Guidelines and Content

Each protocol consisted of seven modular components that were based on recommendations and materials found in our prior treatment programs for behavior disorders (Kolko et al. 2010) and aggressive families (Kolko 1996; Kolko and Swenson 2002), as well as other sources (Kazdin 2011). Each treatment module was administered on an individualized basis and with designated participants (e.g., parent only vs. family members). The use of each module was based on a comprehensive intake assessment that included a set of individualized target behaviors that identified the child’s unique problems (for details, see Kolko et al. 2009). The modules included: (1) child CBT/skills training, (2) child medication for ADHD, (3) parent management training (PMT), (4) parent–child/family therapy, (5) school programming/teacher consultation, (6) peer relations/community activities development, and (7) case/crisis management. As reported in the previous outcome study (Kolko et al. 2009) treatment fidelity ratings from an independent observer who rated videotapes of randomly selected sessions were high for COMM (91 %; range 89–100) and CLINIC (95 %; range 90–100).

Data Analysis Procedures

An effort was made to follow all enrolled cases, per the intent-to-treat model. Preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS (PASW 18) and differences between the COMM and CLINIC cases were evaluated using path models in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2009). Prior to modeling the data, visual inspection of data at both the mean and individual level indicated that neither a linear nor quadratic growth curve model represented the change in the outcomes over time. Many variables showed a noticeable change from baseline to the assessment immediately after treatment, with little linear change occurring across the follow-up assessments. Researchers have recognized that this functional form often occurs in treatment studies and have proposed a piecewise growth curve modeling approach to appropriately model this change over time (for details see Osgood and Smith 1995). Attempts were made to model this functional form; however, adequate fit could not be accomplished. Given the flat growth across post-intervention timepoints, we chose to explore path models examining pretreatment versus posttreatment and pretreatment versus 36 month follow-up outcomes. This allowed for the longest term follow-up to explore whether predictors/moderators were consistent across time (from posttreatment to 36 month follow-up).

Standard procedures for probing the nature and direction of significant interactions were used to examine the associations between specific moderators and outcomes for youth who received treatment in the clinic versus the community (Cohen et al. 2003). Because group effects were examined in our prior study, the main effects for group are not included in the summary tables based on these analyses. Because moderation analysis is particularly informative in understanding differential effectiveness, we first explore whether variables serve as significant moderators and if not, examine their potential as non-specific predictors of treatment outcomes. Interactions were probed utilizing software created by Preacher et al. (2006).

Results

Missing Data Analyses

Of the 144 participants, 47 (33 %) had some missing data for at least one of the six time points. Participants with and without missing data at any time point were compared on treatment condition (one variable), demographic information (three variables), outcome measures at baseline (two variables), and several other variables at baseline (12 variables). The group with missing data had significantly different scores on only two of 18 variables (child adjustment, p = 0.001; SES, p = 0.030). The group with missing data had significantly higher scores on child adjustment but lower SES scores. Overall, the results indicate that the two groups were generally comparable.

Descriptives, Group Comparisons, and Intercorrelations

Child Behavior Outcomes

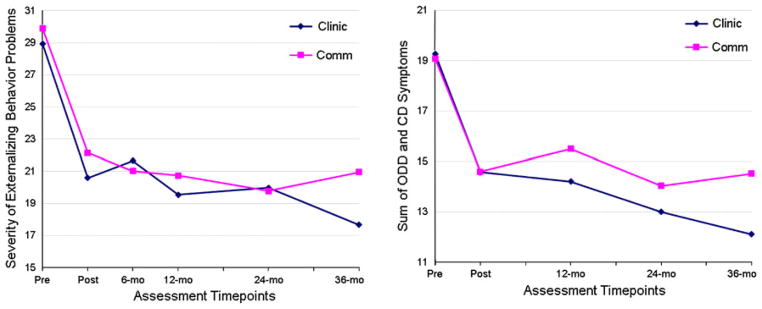

Figure 1 presents the mean raw scores for the CBCL externalizing behavior problems scale in the top panel and parallel means for the number of endorsed DBD symptom in the bottom panel for the CLINIC and COMM intervention conditions from baseline through the final 3-year follow-up assessment. The data indicate that both conditions showed a relatively large reduction in the externalizing problems scores by posttreatment and that this reduction was maintained throughout the remaining 3 years of follow-up. There was also a modest reduction in the number of DBD symptoms exhibited by children in the two conditions by posttreatment which were also maintained during the follow-up period, with the exception of a modest increase in symptoms found at the intervening 2-year follow-up. We examined mean level differences in the two primary outcomes in the CLINIC versus COMM groups at each time point. Results demonstrated that there was a significant difference (p = 0.042) in DBD symptoms at the 36 month follow-up such that the mean number of symptoms for those in CLINIC (M = 12.11) was significantly lower than the mean number of symptoms for those in COMM (M = 14.52). There was also a trend level difference (p = 0.09) in externalizing behavior problems at the 36 month follow-up such that the mean externalizing behavior problems score was lower for those in CLINIC (M = 17.66) than for those in COMM (M = 20.95). Differences between the two groups were not significant at any other timepoints.

Fig. 1.

Mean raw scores for the externalizing behavior problems scale and number of endorsed ODD and CD symptoms for the clinic and community treatment conditions from baseline through 3-year follow-up

Demographics, Predictor and Moderator Variables, and Treatment Parameters

Table 1 presents the descriptive data for the baseline levels of each demographic characteristic, predictor variable, and moderator variable in the CLINIC and COMM intervention conditions as well as descriptive data for the five treatment parameters.

Intercorrelations

An intercorrelation matrix with all predictor or moderator variables showed minimal overlap among variables (range absolute value: 0.00 to 0.46), with most correlations below 0.15. The highest correlation was between parental education and income. A similar examination of treatment parameters revealed a high correlation between hours of PMT and child CBT (r = 0.85, p <0.001). Other correlations were in the low to modest range. Because of interest the in examining the role of child CBT separately from PMT, we retained both variables.

Moderators of Treatment Outcome

In all analyses, baseline level of the outcome measure, either CBCL externalizing behavior problems or the number of DBD symptoms, was controlled. We first explored whether variables served as significant moderators of treatment effects (e.g., the interactions of the predictors with treatment condition). If these interactions were not significant, we examined the potential of these variables to serve as non-specific predictors of treatment outcomes. Predictor results reported in Tables 2 and 3 reflect the predictor only model (with the interaction term removed) when the moderation effect is not significant.

Table 2.

Models examining outcomes for externalizing behavior problems in the modular clinic and community conditions

| Pre to post path model

|

Pre to follow-up path model (36 month assessment)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor (main) effect

|

Interaction effecta

|

Predictor (main) effect

|

Interaction effecta

|

|||||||||

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Demographic and clinical variables | ||||||||||||

| Total income | −0.207 | 0.074 | 0.005** | −0.109 | 0.112 | 0.331 | −0.158 | 0.085 | 0.064 | 0.026 | 0.130 | 0.843 |

| Parental employment | −0.182 | 0.074 | 0.014* | 0.310 | 0.168 | 0.064 | −0.017 | 0.083 | 0.838 | 0.014 | 0.188 | 0.939 |

| Parental education | −0.068 | 0.078 | 0.383 | −2.538 | 1.551 | 0.102 | −0.032 | 0.084 | 0.706 | −0.178 | 0.111 | 0.108 |

| Parental BDI | 0.170 | 0.076 | 0.024* | −0.081 | 0.114 | 0.475 | 0.091 | 0.084 | 0.278 | −0.151 | 0.125 | 0.228 |

| Family conflict | −0.060 | 0.077 | 0.435 | 0.013 | 0.106 | 0.902 | −0.184 | 0.124 | 0.139 | 0.232 | 0.118 | 0.050* |

| Child impairment | 0.338 | 0.108 | 0.002** | −0.197 | 0.099 | 0.046* | 0.091 | 0.099 | 0.355 | −0.160 | 0.110 | 0.147 |

| Teacher report of child aggression | 0.026 | 0.080 | 0.743 | −0.075 | 0.106 | 0.483 | −0.035 | 0.089 | 0.695 | −0.068 | 0.118 | 0.565 |

| ADHD diagnosis | −0.055 | 0.079 | 0.490 | −0.139 | 0.176 | 0.429 | 0.120 | 0.087 | 0.171 | 0.130 | 0.194 | 0.503 |

| Child interpersonal trauma history | 0.058 | 0.077 | 0.449 | −0.008 | 0.144 | 0.953 | −0.030 | 0.085 | 0.722 | −0.160 | 0.159 | 0.313 |

| Treatment parameters | ||||||||||||

| Hours of child CBT | 0.182 | 0.109 | 0.095 | −0.399 | 0.107 | 0.000** | 0.323 | 0.126 | 0.010** | −0.264 | 0.117 | 0.024* |

| Hours of PMT | 0.062 | 0.120 | 0.606 | −0.254 | 0.116 | 0.029* | 0.065 | 0.098 | 0.505 | −0.151 | 0.129 | 0.243 |

| Hours of parent–child treatment | −0.020 | 0.079 | 0.800 | −0.122 | 0.128 | 0.339 | 0.029 | 0.085 | 0.736 | −0.115 | 0.138 | 0.404 |

| Treatment completion | −0.201 | 0.085 | 0.018* | −0.144 | 0.333 | 0.666 | −0.107 | 0.088 | 0.228 | −0.290 | 0.358 | 0.417 |

| Referral for services at discharge | 0.290 | 0.074 | 0.000** | −0.011 | 0.155 | 0.941 | 0.214 | 0.084 | 0.011* | −0.066 | 0.173 | 0.703 |

All models control for baseline CBCL externalizing; standardized values reported

If interaction was not significant, predictor (main effects) are reported from the initial model (without the interaction term)

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.05

Interaction effect = predictor by condition interaction effect

Table 3.

Models examining outcomes for number of endorsed ODD and CD symptoms in modular clinic and community conditions

| Pre to post path model

|

Pre to follow-up path model (36 month assessment)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor (main) effect

|

Interaction effecta

|

Predictor (main) effect

|

Interaction effecta

|

|||||||||

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Demographic and clinical variables | ||||||||||||

| Total income | −0.186 | 0.076 | 0.014* | −0.053 | 0.114 | 0.645 | −0.070 | 0.083 | 0.400 | −0.063 | 0.126 | 0.619 |

| Parental employment | −0.054 | 0.077 | 0.484 | −0.091 | 0.177 | 0.606 | 0.029 | 0.080 | 0.714 | 0.081 | 0.182 | 0.658 |

| Parental education | −0.099 | 0.078 | 0.203 | −0.138 | 0.103 | 0.181 | −0.061 | 0.081 | 0.454 | −0.179 | 0.106 | 0.093 |

| Parental maternal BDI | 0.171 | 0.077 | 0.025* | −0.008 | 0.021 | 0.686 | −0.004 | 0.082 | 0.964 | −0.057 | 0.121 | 0.638 |

| Family conflict | 0.097 | 0.077 | 0.208 | 0.102 | 0.105 | 0.334 | 0.010 | 0.085 | 0.904 | 0.076 | 0.116 | 0.513 |

| Child impairment | 0.176 | 0.106 | 0.096 | −0.204 | 0.100 | 0.041* | 0.042 | 0.088 | 0.631 | −0.024 | 0.107 | 0.820 |

| Teacher report of child aggression | −0.006 | 0.081 | 0.941 | 0.074 | 0.108 | 0.493 | 0.003 | 0.087 | 0.975 | 0.097 | 0.115 | 0.400 |

| ADHD diagnosis | 0.174 | 0.107 | 0.104 | −0.370 | 0.172 | 0.032* | 0.047 | 0.084 | 0.571 | 0.022 | 0.188 | 0.908 |

| Child interpersonal trauma history | 0.154 | 0.077 | 0.046* | −0.242 | 0.141 | 0.085 | 0.081 | 0.083 | 0.326 | −0.237 | 0.150 | 0.113 |

| Treatment parameters | ||||||||||||

| Hours of child CBT | 0.179 | 0.118 | 0.128 | −0.228 | 0.111 | 0.040* | 0.313 | 0.124 | 0.011* | −0.284 | 0.113 | 0.012* |

| Hours of PMT | 0.049 | 0.090 | 0.587 | −0.069 | 0.041 | 0.087 | 0.287 | 0.133 | 0.030* | −0.277 | 0.121 | 0.023* |

| Hours of parent–child treatment | −0.120 | 0.079 | 0.127 | 0.026 | 0.132 | 0.841 | −0.039 | 0.082 | 0.633 | 0.076 | 0.138 | 0.581 |

| Treatment completion | −0.144 | 0.083 | 0.081 | 0.122 | 0.336 | 0.717 | −0.114 | 0.084 | 0.175 | 0.211 | 0.344 | 0.540 |

| Referral for services at discharge | 0.301 | 0.073 | 0.000** | −0.158 | 0.158 | 0.314 | 0.092 | 0.083 | 0.267 | −0.193 | 0.171 | 0.260 |

All models control for baseline DBD symptoms; standardized values reported

If interaction was not significant, predictor (main effects) are reported from the initial model (without the interaction term)

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.05

Interaction effect = predictor by condition interaction effect

Posttreatment

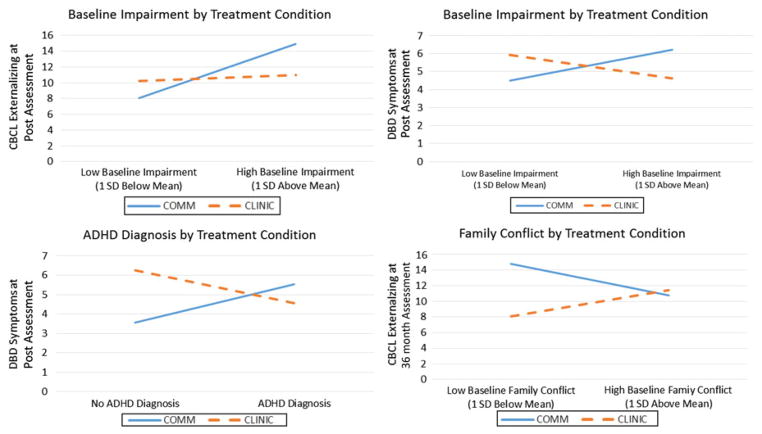

Analyses examining the overall effects of the predictor variables as well as the interactions of the predictors with condition that are designed to identify treatment moderation on the CBCL externalizing behavior problems and the number of DBD symptoms outcomes are found in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Analyses of post-intervention outcomes identified three significant interactions that reflect moderator effects. For CBCL externalizing problems at posttreatment, higher baseline impairment among those in COMM was associated with higher posttreatment externalizing whereas for those in CLINIC, baseline impairment was not differentially related to posttreatment externalizing. Similarly, for the number of DBD symptoms at posttreatment, higher baseline impairment among those in COMM was associated with higher posttreatment DBD symptoms whereas higher baseline impairment among those in CLINIC was associated with lower posttreatment DBD symptoms. In addition, whether or not children were diagnosed with ADHD moderated posttreatment DBD symptoms. Those with no ADHD diagnosis in COMM had lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment whereas those with no ADHD diagnosis in CLINIC had higher DBD symptoms at posttreatment. For those with an ADHD diagnosis, treatment group was not differentially related to DBD symptoms at posttreatment. These moderator relationships are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Moderator effects for the externalizing behavior problems scale and total number of endorsed ODD and CD symptoms

Thirty-Six Month Follow-Up

One variable moderated CBCL externalizing behavior problems measured at the 36 month follow-up: those with lower baseline family conflict in COMM had higher externalizing behavior problems at the 36 month follow-up whereas those with lower baseline family conflict in CLINIC had lower externalizing behavior problems. For those with high baseline family conflict, treatment group was not differentially related to externalizing behavior at the 36 month follow up. This moderator relationship is depicted in Fig. 2. There were no significant moderators of outcome based on the number of DBD symptoms at follow-up.

Predictors of Treatment Outcome

Posttreatment

Several variables were found to significantly predict both CBCL externalizing behavior problems and DBD symptoms at posttreatment as shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Children whose parents had lower (vs. higher) levels of depressive symptoms had lower externalizing problems and lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment. Similarly, children with higher family income had lower externalizing problems and lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment. There were also variables that significantly predicted only one of the two outcomes. Children whose parents were employed had lower externalizing problems at posttreatment, and children without a history of interpersonal violence had lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment.

Thirty-Six Month Follow-Up

There were no significant overall predictors of long-term improvement in either the severity of externalizing behavior problems or number of significant DBD symptoms.

Treatment Parameters

Posttreatment

We examined the role of the five treatment parameters in relation to improvement in the two primary outcomes. Overall, children who completed treatment or did not need a referral for additional services at discharge showed lower externalizing problems at posttreatment (see Table 2). In addition, not needing a referral for additional services was associated with lower of DBD symptoms at posttreatment (see Table 3). In CLINIC only, the number of hours of child CBT and parent training were associated with lower externalizing problems at posttreatment. Also, in CLINIC only, the number of hours of child CBT was associated with lower DBD symptoms.

Three-Year Follow-Up

Similar to posttreatment outcomes, children who did not need a referral for additional services showed lower scores on externalizing problems (see Table 2). In addition, in CLINIC only, the number of hours of child CBT was associated with lower scores on externalizing problems. The number of hours of child CBT and parent training were associated with lower DBD symptoms in CLINIC but not in COMM.

Discussion

This study examined putative predictors and moderators of treatment outcome, and treatment parameter–outcome relationships, based on a recent clinical trial comparing the effects of a modular treatment that was applied by study clinicians in community settings (COMM) or a clinic office (CLINIC) for children with DBD. Outcome measures reflected change in the severity of externalizing behavior from the CBCL and DBD symptoms from the K-SADS diagnostic interview by posttreatment assessment and final 3-year follow-up. A few predictors, moderators, and treatment parameters were related to each outcome. The limitations and implications of these findings for maximizing benefits and personalizing treatment approaches for children’s behavior disorders are discussed.

There were few moderators of outcome, which may not be surprising given the use of two parallel interventions. In COMM, children with higher baseline impairment had higher scores on posttreatment externalizing behavior whereas for the clinic group, baseline impairment was not differentially related to posttreatment externalizing behavior. Similarly, for the number of DBD symptoms at posttreatment, higher baseline impairment among those in COMM was associated with higher DBD symptoms whereas for those in CLINIC, higher baseline impairment was associated with lower DBD symptoms. These results are in line with previous findings of greater effects of interventions for those with higher baseline problems (e.g., Chamberlain et al. 2008; Reid et al. 2004; Shaw et al. 2006; Tein et al. 2004). What is novel about these results is that they are based on a comparison of the same modular treatment implemented in different settings and suggest treatment in a clinical (vs. community) setting may be more beneficial for children with high baseline impairment.

Whether or not children were diagnosed with ADHD also moderated posttreatment level of DBD symptoms. Those without an ADHD diagnosis in COMM had lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment. Since the rate and impact of ADHD study medication use did not vary by condition (Kolko et al. 2009), this difference is unlikely to be due to a lower rate of ADHD treatment or response in COMM. However, families in COMM did not meet face to face with the study psychiatrist for medication prescriptions and monitoring, which may have limited the impact of this module for those with ADHD. Thus, it may be worth exploring some additional programming or contingencies that might further enhance the impact of modular treatment in those children with comorbid ADHD who are treated in the community. Severity of behavior problems or comorbid attentional problems have been found related to greater treatment response, albeit poorer overall posttreatment outcome, in several samples (Beauchaine et al. 2005; Kazdin and Whitley 2006; Lavigne et al. 2008a), although severity has not always been related to better outcome (Gardner et al. 2010; van den Hoofdakker et al. 2010).

Finally, there was only one moderator of long-term outcome. Specifically, those with lower baseline family conflict in COMM had higher externalizing behavior problems at the 36 month follow-up, whereas those with lower baseline family conflict in CLINIC had lower externalizing problems. For those with high baseline family conflict, intervention group (COMM vs. CLINIC) was not differentially related to externalizing behavior at the 36 month follow up. This suggests that families experiencing lower levels of conflict may benefit more from treatment in a clinic. Interestingly, for those with high family conflict, setting does not seem to matter. Perhaps high family conflict represents a risk factor that may be linked to child behavior, and modular treatment addressing child, parent, and family domains may adequately address this risk present for child BP, regardless of the setting in which it is given. There were no significant moderators of outcome based on the number of DBD symptoms at follow-up.

In terms of the significant predictor analyses, children whose parents reported higher depressive symptoms, whose families had lower incomes, and whose parents were unemployed had higher externalizing symptoms at posttreatment. Similarly, children whose parents reported higher depressive symptoms, whose families had lower incomes, and who had a history of interpersonal violence had higher DBD symptoms at posttreatment. One implication of these results is the potential need to broaden the scope of intervention to include some unique components that can more fully target socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., low income and unemployed families), parental psychopathology, such as depression, and child exposure to interpersonal violence. In terms of interpersonal violence, several evidence-based interventions for violence exposure incorporate general CBT methods as well as procedures that are more trauma-specific in nature (Jaycox et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2011; Kolko et al. in press, 2011b). Some evidence among delinquent females suggested that a combination of delinquency and trauma treatment methods is superior to delinquency treatment alone (Chamberlain and Smith 2010), which may highlight the potential utility of an integrated intervention. With regard to the parental depression findings, perhaps the inclusion of caregiver engagement, psychoeducation, and self-control skills training would enhance receptivity to applying parent management skills and family communication and problem-solving routines. However, it is worth noting that none of these variables predicted either outcome at long-term follow-up.

Among the treatment parameters evaluated herein, those who were not referred for additional services in both conditions showed lower DBD symptoms at posttreatment and lower externalizing problems at posttreatment and 36-month follow-up. Treatment completers in both conditions showed lower externalizing symptoms at posttreatment. Since treatment in both conditions included multiple components, those who did not need additional referrals or who were completers may have made gains due to greater to exposure to the primary content (child, parent, and family visits) than those who received less exposure. Our analysis of specific dose–response relationships was designed to explore the types of content related to improvements in these outcomes. Interestingly, none of these treatment parameters was related to improvement in externalizing problems in both conditions: the significant interactions demonstrate that the effect of hours of these types of treatment varies based on treatment condition. That is, at posttreatment, the amount of exposure to child CBT and parent training was associated with lower scores on externalizing problems, and hours of child CBT was associated with lower DBD symptoms in CLINIC only. Likewise, at 3-year follow-up, hours of child CBT was associated with lower scores on externalizing problems and hours of child CBT and parent training was associated with lower DBD symptoms in CLINIC only. Insofar as most intervention studies primarily deliver or examine parental or caregiver directed intervention exposure (see Kelley et al. 2010), the influence of child involvement in CBT on treatment response in the short-and long-run found in this study suggests the potential benefit for targeting children or adolescents in multimodal treatment and evaluating the contribution of their active involvement to treatment effectiveness. One possible explanation for the setting difference may be due to the greater structure that can be imposed for sessions in the clinic versus home. Anecdotal reports from clinicians in COMM highlighted certain obstacles to successful administration of the child, parent, and family modules due to partial no-shows, noncompliance, and/or numerous distractions during home visits, as well as the lack of privacy for parents or children, all of which may be more difficult to overcome in a client’s home than in the therapist’s office. These potential setting variations are important to examine as interventions conducted in both settings have been encouraged for DBD children and adolescents (see Kazdin 2011).

Collectively, these findings lend some support for a treatment model that includes both specific content and general components delivered to both children and care-givers in individual and family sessions (Hagen et al. 2011; Kaminski et al. 2008; Webster-Stratton and Reid 2011). The importance of individualizing or personalizing a given family’s treatment has been advocated in recent federal initiatives and conceptual models (Bertakis and Azari 2011; Stewart et al. 2000). As few studies of DBD treatment have examined the role of these and other treatment parameters, it is difficult to determine the generality of these results. Further, our results stand in contrast to the relative absence of dose–response relationships found in the child/adolescent program evaluation literature (Bickman et al. 2002), possibly because most of those early studies were based on very different samples, study designs, treatment content and methods, and analytic approaches, including variation in the level of child participation in treatment. However, studies based on more similar characteristics have reported some dose–response relationships (Kennard et al. 2009; Lavigne et al. 2010; Reid et al. 2003), including a recent study of children exposed to intimate partner violence which found that the dose of maternal treatment in a clinic setting predicted better child adjustment (Graham-Bermann et al. 2007). In addition, a recent prevention trial found that active engagement in parent management training may also contribute to changes in parental practices (Nix et al. 2009). These findings highlight the need to incorporate specific methods that enhance treatment initiation, retention, and completion, such as incentives or engagement strategies that promote ongoing participation (Nix et al. 2009).

The limitations of this study deserve mention. The study compared parallel modular content applied by study clinicians in two alternative settings, which would make it less likely to find moderators of treatment. The sample size was modest and, when added to some of the attrition found during the 3 year follow-up, may have limited our ability to detect significant group differences in moderators or predictors. In addition, it would have been useful to more fully evaluate the obstacles or challenges to delivering treatment that the clinicians faced in each treatment. Such information may help to explain some of the study’s findings and identify key targets for treatment model refinement. The previous outcome study (Kolko et al. 2009) found that parents reported significantly fewer obstacles related to competing activities/life stressors in COMM than CLINIC, but the scores were comparable regarding the relevance of treatment, relationship with therapist, treatment issues, or critical events factors.

In summary, we found modest support for the impact of child comorbidity in predicting overall outcome, minimal support for the adverse effects of contextual characteristics (e.g., parental dysfunction, family conflict) on outcome in the community (vs. clinic), and modest support for the contribution of dose of parent and child treatment to enhanced outcome. Thus, this study of modular treatment applied in the community or an outpatient clinic for children diagnosed with behavior disorders identified relatively few variables across the child, parent, and family domains that moderated or predicted changes in the severity of externalizing behavior problems or the number of DBD symptoms. The effects of a comparable treatment package conducted in an outpatient clinic or community settings were fairly robust across a range of characteristics examined, both after intervention and at 3-year follow-up. Still, certain characteristics may merit further attention during treatment as they predicted less change in the children’s behavior problems in the overall sample (family income, parental employment, parental depression, child interpersonal trauma history) or moderated treatment outcome in CLINIC and COMM (baseline level of child impairment, comorbid ADHD, family conflict). Some treatment dose variables and discharge status were related to improvement in outcomes at posttreatment, especially in CLINIC. These findings suggest that providing greater attention to a few child, parent, and family variables, and the treatment dose for children and parents, may influence the level of improvement found among behavior-disordered children who are treated in the clinic or community settings. Hopefully, such information may facilitate more personalized treatment applications designed to maximize initial and long-term clinical impact of interventions for children with disruptive behavior disorders (NIMH 2008).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jon Hart, Brent Dupay, Chelsea Weaver, and the staff of the Resources to Enhance the Adjustment of CHildren (REACH) program. Research was supported through NIMH Grant 057727.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth C. Shelleby, Email: ecs38@pitt.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, 4425 Sennott Square, 210 S. Bouquet St., Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA

David J. Kolko, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar B, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E. Distinguishing the early-onset/persistent and adolescence-onset antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(2):109–132. doi: 10.1017/S0954579-400002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of 1-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):371–388. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertakis KD, Azari R. Determinants and outcomes of patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85(1):480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Andrade AR, Lambert EW. Dose response in child and adolescent mental health services. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4(2):57–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1015210-332175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H, Shaffer D, Fisher P, Gould MS. The Columbia impairment scale (CIS): Pilot findings on a measure of global impairment for children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(03):467–488. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk JA, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9(1):17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Smith DK. Multidimensional treatment foster care for adolescents: Processes and outcomes. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 243–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral science. 3. Mahaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Murray LK. Trauma-focused CBT for youth who experience ongoing traumas. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;35:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Racusin R, Daviss WB, Ellis C, Thomas J, Rogers K. Trauma exposure among children with oppositional defiant disorder and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:786–789. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Connell A, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Moderators of outcome in a brief family-centered intervention for preventing early problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):543–553. doi: 10.1037/a0015622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Hutchings J, Bywater T, Witaker C. Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(4):568–580. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Bermann S, Lynch S, Banyard VL, DeVoe ER, Halabu H. Community-based intervention for children exposed to intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):199–209. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen KA, Ogden T, Bjornebekk G. Treatment outcomes and mediators of parent management training: A one-year follow-up of children with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(2):165–178. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and substance-dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A, Redlich F. Social class and mental illness: A community study. New York, NY: Wiley; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Walker DWL, Audra K, Gegenheimer KL, et al. Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused therapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(2):223–231. doi: 10.1002/jts.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, Rao U, Ryan ND. KIDDIE-SADS-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) Pittsburgh, PA: Instrument developed at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment research: Advances, limitations, and next steps. American Psychologist. 2011;66(8):685–698. doi: 10.1037/a0024975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Siegel TC, Bass D. Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(5):733–747. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Comorbidity, case complexity, and effects of evidence-based treatment for children referred for disruptive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):455–467. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley S, de Andrade A, Sheffer E, Bickman L. Exploring the black box: Measuring youth treatment process and progress in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(3):287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard BD, Silva SG, Tonev S, Rohde P, Hughes JL, Vitiello B. Remission and recovery in the treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Acute and long-term outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009a;48(2):186–195. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819176f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard BD, Weersing VR, Shamsedden W, Porta G, Hughes J, Emslie GJ. Effective components of TORDIA cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: Preliminary findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009b;77(6):1033–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0017411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling Å, Forster M, Sundell K, Melin L. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of parent management training with varying degrees of therapist support. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ. Individual cognitive-behavioral treatment and family therapy for physically abused children and their offending parents: A comparison of clinical outcomes. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:322–342. doi: 10.1177/1077559596001004004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Herschell AD, Hart JA, Holden EA, Wisniewski SR. Dissemination of AF-CBT to community practitioners serving child welfare and mental health: A randomized trial. Child Maltreatment. doi: 10.1177/1077559511427346. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Campo JV, Kelleher K, Cheng Y. Improving access to care and clinical outcome for pediatric behavioral problems: A randomized trial of a nurse-administered intervention in primary care. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31(5):393–404. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181dff307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Cheng Y, Campo JV, Kelleher K. Moderators and predictors of clinical outcome in a randomized trial for behavior problems in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011a doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Dorn LD, Bukstein OG, Pardini DA, Holden EA, Hart JA. Community vs. clinic-based modular treatment of children with early-onset ODD or CD: A clinical trial with three-year follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:591–609. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Iselin AM, Gully KJ. Evaluation of the sustainability and clinical outcome of alternatives for families: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (AF-CBT) in a child protection center. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011b;35(2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Swenson CC. Assessing and treating physically abused children and their families: A cognitive behavioral approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Lochman JE. Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):373–382. doi: 10.1037/a0015954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, Binns HJ, Keller J, Pate L. Predictors and correlates of completing behavioral parent training for the treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in pediatric primary care. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(2):198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, Cicchetti C, Jessup BW, Arend R. Predictor and moderator effects in the treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008a;33(5):462–472. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, Cicchetti C, Pochyly J, Arend R. Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: A comparison of three models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008b;33(5):449–461. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman EL, Boyle MH, Cunningham C, Kenny M, Sniderman C, Duku E. Testing effectiveness of a community-based aggression management program for children 7 to 11 years old and their families. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1085–1093. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000228132.64579.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness of the Coping Power Program and of classroom intervention with aggressive children: Outcomes at a 1-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:493–515. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence (First volume of the Pittsburgh Youth Study) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC. A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CRJ, Forgatch MS. Preventing problems with boys’ noncompliance: Effects of a parent training intervention for divorcing mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:416–428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart MR, Priester PE, Davies WH, Azen R. Differential effectiveness of behavioral parent-training and cognitive-behavioral therapy for antisocial youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:527–543. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilloway S, Mhaille GN, Bywater T, Furlong M, Leckey Y, Kelly P, et al. A parenting intervention for childhood behavioral problems: A randomized controlled trial in disadvantaged community-based settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):116–127. doi: 10.1037/a0026304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Poverty, parenting, and children’s mental health. American Sociological Review. 1993;58(3):351–366. [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart P, Sanders MR. Mediators and moderators of change in dysfunctional parenting in a school-based universal application of the Triple-P Positive Parenting Programme. Journal of Children’s Services. 2007;2(1):4–17. doi: 10.1108/17466660200700002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Insel PM, Humphrey B. Family work and group environment scales. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Gray RO, Keane SP, Hurst RM, Mitchell JT, Warburton JB, Chok JT. A modified DBT skills training program for oppositional defiant adolescents: Promising preliminary findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1811–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) NIH Publication No. 08-6368. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Mental Health; 2008. The National Institute of Mental Health Strategic Plan. [Google Scholar]

- Nix RL, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ. How attendance and quality of participation affect treatment response to parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):429–438. doi: 10.1037/a0015028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Smith GL. Applying hierarchical linear modeling to extended longitudinal evaluations. Evaluation Review. 1995;19:3–38. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9501900101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C, Baydar N. Halting the development of conduct problems in Head Start children: The effects of parent training. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):279–291. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Follow-up of children who received the Incredible Years Intervention for oppositional-defiant disorder: Maintenance and prediction of 2-year outcome. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34(4):471–491. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80031-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, McGrath PJ. Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problem: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):99–111. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-7610.2005.01544.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(1):1. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelleby EC, Shaw DS. Outcomes of parenting interventions for child conduct problems: A review of differential effectiveness. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0431-5. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. The Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolk MN, Mesman J, van Zeijl J, Alink LRA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, et al. Early parenting intervention: Family risk and first-time parenting related to intervention effectiveness. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2008;17(1):55–83. doi: 10.1007/s10826-007-9136-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson CC, Schaeffer CM, Henggeler SW, Faldowski R, Mayhew AM. Multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect: A randomized effectiveness trial. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24(4):497–507. doi: 10.1037/a0020324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tein JY, Sandler IN, MacKinnon DP, Wolchik SA. How did it work? Who did it work for? Mediation in the context of a moderated prevention effect for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):617–624. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempel A, Herschell AD, Kolko DJ. Conduct disorder. In: Cautin R, Lillenfeld S, editors. The encyclopedia of clinical psychology. Blackwell; New York, NY: (in press) [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoofdakker BJ, Nauta MH, van der Veen-Mulders L, Sytema S, Emmelkamp PMG, Minderaa RB. Behavioral parent training as an adjunct to routine care in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Moderators of treatment response. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(3):317–326. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jspo6o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton CH, Reid MJ. Combining parent and child training for young children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(2):191–203. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]