Abstract

Anaphylaxis is a sudden immune reaction against an allergen that can potentially lead to Anaphylactic Shock (AS). This immune reaction is characterized by an increase in Immunoglobulin-E (IgE) type of antibodies that bind with FcεRI receptors on mast cells to release inflammatory mediators. Various intracellular signaling molecules downstream of IgE/ FcεRI axis play a potential role in cytokine, chemokine and eicosanoid secretion as well as degranulation of immune cells causing vasodilation, vascular permeability, and reduction of intravascular volume leading to cardiovascular collapse. Here, we discuss the cellular machinery of anaphylaxis and the de novo paradigm shift in the cellular aspects of AS.

Keywords: Anaphylaxis, Anaphylactic shock, Immunoglobulin E, Mast cells, Cytokines, Chemokines, Paradigm shift

Background

Anaphylaxis is an immediate Type I hypersensitivity reaction triggered by sudden release of immune cell mediated release of mediators into the circulatory system [1]. Anaphylaxis is graded using a scale of 0 to IV and the stage III and above corresponds to life-threatening Anaphylactic Shock (AS) [2]. AS is sudden and making the prevention in most cases difficult in an emergency situation. Without immediate treatment, AS might lead to substantial morbidity and mortality; within minutes this sudden clinical response can be lethal. The lifetime probability of an individual to develop anaphylaxis may be from 1 to 3 % with a mortality rate of about 1 % [3].

AS leads to cardiovascular collapse that occurs after the interaction of antigen and antibody [4] which in most cases results from immunogenic reactions to foods [5, 6], medication [7–12], chemicals [13], dental materials [14], insect bites [15], vaccines [16, 17], therapeutic antibodies [18–21], herbal extracts [22], exercise in rare cases [23] and other agents [9] ,24–29] that can induce the degranulation of mast cells and basophils (18, 31). Some of the symptoms of AS includes cardiac arrhythmias, diffuse erythema, headache, nausea, unconsciousness and cardiovascular collapse in severe cases [6, 30]. Most often these signs and symptoms occur within 30 min of allergen exposure, however, in some cases severe anaphylactic reactions may take a progressive path regardless of adequate treatment; even in the case of an initial favorable response to therapy, lifethreatening symptoms may recur due to late-phase reactions from 6 to 12 hours after the initial events of AS [6, 30].

However, very little advancement has been achieved in the effective treatment and management of anaphylaxis [31, 32]. The prophylaxis is confined to total avoidance, allergen specific desensitization, and proper treatments, including antihistamines, adrenaline, corticosteroids etc., [31, 32]. On the other hand, various studies using in vitro, in vivo and in silico models have identified various cellular and molecular mechanisms, either to enhance or attenuate, the AS [32–41]. Here, we discuss the cellular machineries implicated in AS

Distinct cellular cascades of AS:

Studies conducted on the animal models of murine systemic anaphylaxis show that the anaphylaxis is rapid and hypothermia, hypotension, diminished movement, piloerection and scratching [42, 43]. During anaphylaxis, the crosslinking of the multivalent FceRI expressed on mast cells and basophils [44, 45] by allergen induces the activation of an array of signaling pathways [34, 46], resulting in degranulation, lipid mediator release and cytokine gene transcription, culminating in secretion of cytokines and chemokines that play a central role in allergic reactions [46, 47]. Novel cytokines such as Interleukin-33 (IL-33) may play a potential role in AS. It is the ligand for ST2 receptor, and the IL-33/ST2 axis is implicated in various human diseases including allergy and asthma. The ST2 is expressed predominantly in immune cells such as mast cells and type 2 helper T- cells (Th2). Advancing research into the role of IL-33/ST2 using in vitro, in vivo and in silico models of allergy and anaphylaxis may perhaps provide novel targets for the robust management and treatment of an extensive range of allergic disorders in humans.

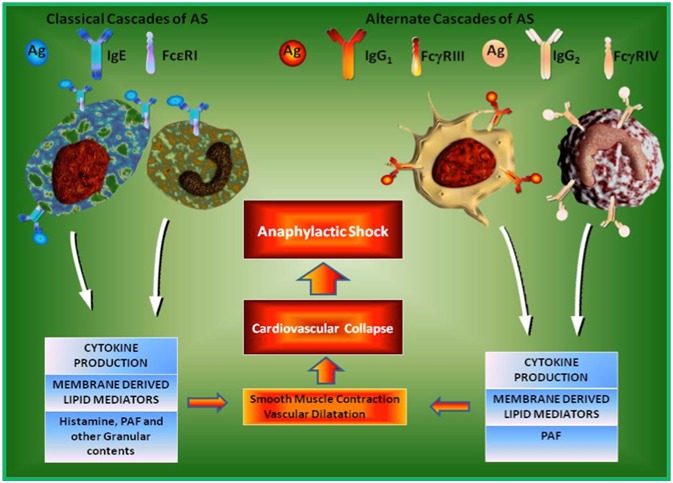

Anaphylaxis or AS can be mediated by distinct cellular and molecular cascades in both humans and mouse, namely mast cell mediated (Conventional or Classical or Orthodox) and macrophage mediated (Alternate or Unconventional or Unorthodox) cascades [40] (Figure 1). The classical cascade is initiated by the sensitization of mast cells by IgE antibodies coupled with high affinity FceRI receptors on the cell surface followed by binding of antigens leading to mast cell degranulation and the release of histamine as well as other proinflammatory molecules. However, histamine is principally responsible for the induction of AS [33, 38].

Figure 1.

Cellular Cascades of Anaphylactic Shock (AS). Anaphylactic shock is a rapid allergic reaction involving multiple organs including the bronchial and cardiovascular system. It is induced either by the mast cells or basophils triggering the Classical Molecular Cascades of AS. On the other hand, macrophages as well as neutrophils trigger Alternate Molecular Cascades of AS. Classical Cascade is induced even when IgE bound with the FceRI receptor on the mast cells and basophils cross-links with allergen/antigen leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines, lipid mediators, histamine, PAF and other granular contents. The Alternate Cascade is induced when both antigen specific IgG and IgE are present and IgG concentration is more than IgE, in this state, antigen/allergen complex binds with FcgRIII/FcgRIV on the surface of macrophages and neutrophils respectively. Except histamine, all other mediators of AS such as cytokines, lipid mediators and PAF are released from both macrophages and neutrophils.

On the other hand, the alternate cascade of AS can be partially induced by IgG antibodies through the stimulation of FcγRIII, a low-affinity IgG receptor, on macrophages [36]. Most importantly, PAF is mainly responsible for the initiation and progression of AS in the alternate cascade [30, 41]. Consequently, the alternative cascade can be induced in mice with monoclonal antibody 2.4G2 that directly binds with FcγRIII on macrophages [30, 40]. The evidence for the alternate cascade of AS has been demonstrated in mice that lacked IgE [39], FceRI [33] and mast cells (c-kit–deficient W/Wv mice) [30, 35]. The anaphylaxis induced by any one of these cascades deactivates the initiation of AS through the other pathway [30, 40].

Neutralizing the neutrophils to ameliorate AS – A novel paradigm shift:

Among the leukocytes, neutrophils are the primary immune cells transmigrate to the sites of infection or tissue damage in the acute inflammatory response(s) [43]. Neutrophils migrate through the endothelial layer of the blood vessels by a process termed as neutrophil extravasation. Deciphering the gene regulation of this extravasation phenomenon is one of the chief objective of the current immunological research to reduce the severity of various diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), asthma, atherosclerosis, ulcerative colitis (UC) etc., [48] Conversely, the critical role of neutrophils, a major innate immune effector cell, in AS was so far not very well characterised.

Very recently, Jönsson et al. showed that anaphylaxis could also be triggered in mast cell-deficient mice as well as in 5KO mice [49]. The 5KO mice administered with FcγRIV-specific blocking antibodies were protected from Active Systemic Anaphylaxis (ASA), pointing out that an anaphylactic reaction can be induced through FcγRIV activation itself. Intriguingly, FcγRIV is expressed macrophages and neutrophils, but not by immune cells playing a major role in the induction of classical cascades of AS such as mast cells and basophils. Additionally, the systemic luminescence experiments precisely indicated that neutrophils were activated within minutes of ASA induction. Besides, reduction of neutrophils protected 5KO mice from AS, reduction of macrophages and monocytes did not attenuate the induction of ASA.

Moreover, Jönsson et al., deciphered that neutrophil reduction protected wild-type (WT) mice from Passive Systemic Anaphylaxis (PSA) induced by polyclonal IgG antibodies, whereas mice lacking both mast cells and basophils were still vulnerable to anaphylaxis. Therefore, neutrophils are not only responsible for the development of IgG-induced PSA but are very much necessary for the triggering of anaphylactic reaction in this in vivo model. These interesting discoveries lead the authors to study the role of neutrophils in ASA in WT mice in order to rule out the embryonic complementation or adaption of KO mice during the embryonic development to overcome the lack of a particular gene and use other alternate pathways for a particular biological function [40]. Surprisingly, neutrophil depletion potentially attenuated the severity of the anaphylactic reaction and blocked the ASA-associated mortality in WT mice.

Treating WT mice with a histamine receptor antagonist mildly ameliorated the severity of ASA, whereas antagonists of the receptor for PAF protected from ASA related mortality. Therefore, the ability of neutrophils to steer ASA, as well as, PSA may at least in part depend on their secretion of PAF. Furthermore, the transfer of human neutrophils restores ASA susceptibility in Fc receptor γ-chain KO mice, which are usually resistant to ASA, Jönsson et al., provided proof that neutrophils might also be potentially playing a decisive role in the development of AS in humans. These findings vouch for a notion that the neutrophils are also important in triggering anaphylaxis in certain immunological milieu in mice and humans. Hence, designing therapeutic modalities to specifically target the mediators of anaphylaxis such as PAF, released from neutrophils, in addition to mast cells, basophils and macrophages, may lead to more effectively neutralize the AS in humans in a typical clinical setting.

Conclusion

AS and other types of allergies are constantly increasing in the society. The patients who develop AS are treated in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) initially with intramuscular injection of epinephrine and intravenous fluid administration followed by both antihistamines and corticosteroids, if necessary, as determined by the Physician [50, 51]. However, the modulation of FceRI responses is currently being used as a principal therapeutic strategy in allergic disorders [52– 56]. The Classical Cascade is the major target for the attenuation of IgE-mediated allergic diseases. Furthermore, anti-IgE monoclonal antibody therapy to allergic patients has exhibited remarkable inhibition and, thus, an effective therapeutic for AS [18, 19]. Interestingly, the recent findings by Jönsson et al. [49] signify a de novo paradigm shift that the neutrophils are also important in triggering anaphylaxis in mice and humans. Hence, designing therapeutic modalities to specifically targeting the mediators of anaphylaxis such as PAF, released from neutrophils, in addition to mast cells, basophils and macrophages, may be useful to effectively neutralize the AS in humans.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the NSTIP strategic technologies program in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) Project Numbers 12-BIO2719-03 and 12-BIO2267-03. The authors also acknowledge with thanks the Science and Technology Unit (STU), King Abdulaziz University (KAU) for technical support. In addition, authors would like to acknowledge the wonderful figure generated by the technical team of Beacon Biosoft (www.beaconbiosoft.com).

Footnotes

Citation:Pushparaj et al, Bioinformation 11(1): 043-046 (2015)

References

- 1.Brown AF. J Accid Emerg Med. 1995;12:89. doi: 10.1136/emj.12.2.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000;112:149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp SF, Lockey RF. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:341. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stopfkuchen H. Ther Umsch. 1994;51:598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khodoun M, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:342. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drouet M, et al. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 2001;33:163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colom J, et al. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0546(09)70252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joly V, et al. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:269. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200207000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thierrin L, et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;140:140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber-Mani U, Pichler WJ. Allergy. 2008;63:785. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maillo L. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:407. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres MJ, et al. Allergy. 1999;54:936. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ionescu A. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:707. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangemi S, et al. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dantas-Torres F, et al. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baer GM, et al. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1962;141:1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jankowiak J, Straburzynski G. Acta Physiol Pol. 1965;16:497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kangueane P, et al. Front Biosci. 2005;10:879. doi: 10.2741/1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leavy O. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:297. doi: 10.1038/nri2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barros VR, et al. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:579. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baudouin V, et al. Transplantation. 2003;76:459. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000073809.65502.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji KM, et al. Allergy. 2009;64:816. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehiri N, et al. Tunis Med. 2008;86:78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu YL, et al. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;25:332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji KM, et al. Allergy. 2008;63:1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartmann MC, et al. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:e136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musio S, et al. Lab Invest. 2009;89:398. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wicki J, et al. Allergy. 1999;54:768. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kos V. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelman FD, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:449. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.12.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones GJ. Emerg Nurse. 2002;9:29. doi: 10.7748/en2002.03.9.10.29.c1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson RF, Peebles RS. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;25:695. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-860983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dombrowicz D, et al. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:915. doi: 10.1172/JCI119256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein B, et al. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:1213. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ha TY, et al. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1986;80:85. doi: 10.1159/000234031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jankovic D, et al. J Immunol. 1997;159:1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korhonen H, et al. J Exp Med. 2009;206:411. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyajima I, et al. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:901. doi: 10.1172/JCI119255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oettgen HC, et al. Nature. 1994;370:367. doi: 10.1038/370367a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strait RT, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:658. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.123302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terashita Z, et al. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komai-Koma M, et al. Allergy. 2012;67:1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Issuree PD, et al. FASEB J. 2009;23:2412. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-130542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz LB. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;457:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz LB. Clin Allergy Immunol. 2002;16:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melendez AJ. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2969. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jayapal M, et al. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar SD, et al. Bioinformation. 2011;6:111. doi: 10.6026/97320630006111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonsson F, et al. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1484. doi: 10.1172/JCI45232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobsen J, et al. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:315. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045003315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reimers A, Muller U. Ther Umsch. 2001;58:325. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.58.5.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garman SC, et al. Cell. 1998;95:951. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garman SC, et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:973. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garman SC, et al. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:1049. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinet JP. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:603. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kinet JP, et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:931. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]