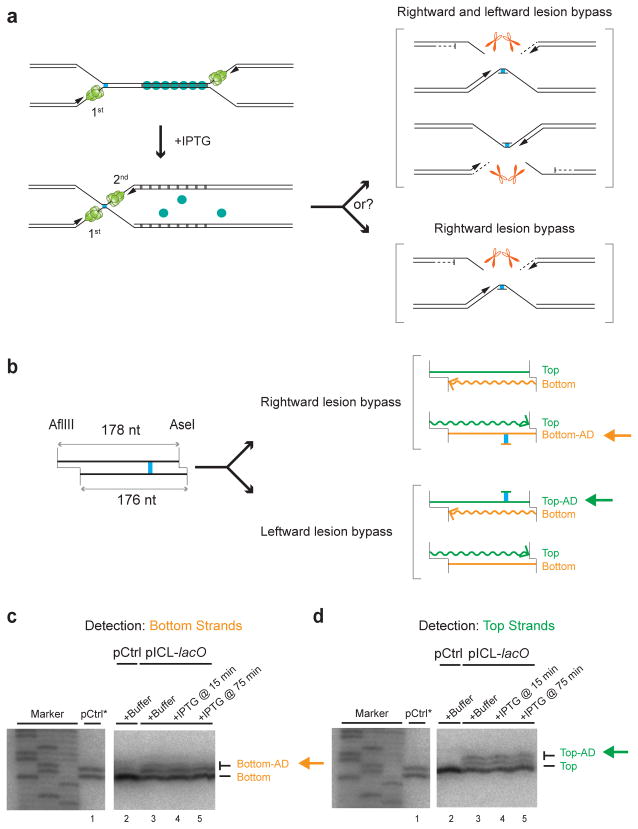

Figure 4. The order of replisome arrival at an ICL does not determine which leading strand undergoes lesion bypass.

(a) Scheme to determine whether the order in which the two forks arrive at an ICL dictates which parental strand is used as the lesion bypass template.

(b) Schematic depiction of final repair products after AflIII and AseI digestion, depending on which leading strand undergoes lesion bypass. Note that AflIII and AseI generate different sized overhangs, allowing us to differentiate top (178 nt) and bottom (176 nt) strands. Top-AD or Bottom-AD: top or bottom strand containing an adduct.

(c, d) Strand-specific Southern blotting to detect the adducts. pCtrl or pICL-lacO was replicated in the presence of buffer or LacI, and IPTG was added at the indicated times. After 6 hours, repair products were digested with AflIII and AseI, separated on a sequencing gel, and analyzed with strand-specific Southern blotting to visualize the bottom (c) or top (d) strands. To generate size markers for the top (178 nt) and bottom (176 nt) strands (lane 1), pCtrl was replicated in the presence of [α-32P]dATP (pCtrl*), and was analyzed on the same sequencing gel as the strand-specific Southern after AflIII and AseI digestion. The fact that no top (c, lane 2) or bottom strand (d, lane 2) was detected in Southern blotting of pCtrl established the strand-specificity of the blotting protocol. Uncropped images of Figs. 4c and 4d are presented in Supplementary Data Set 1d.