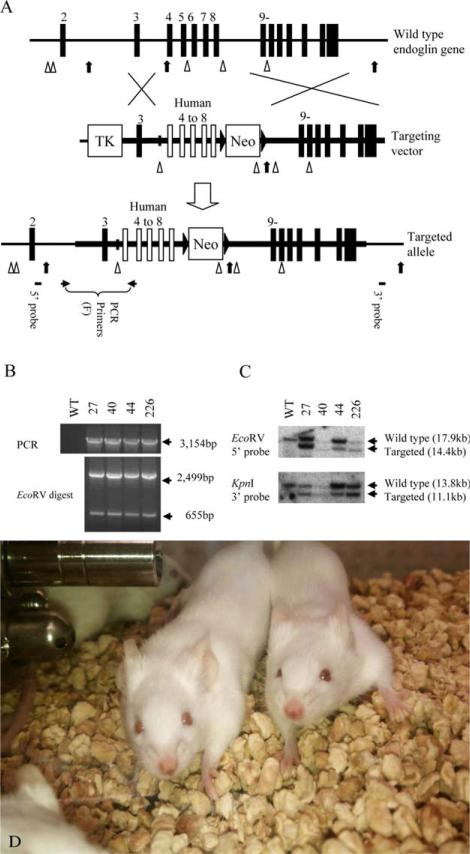

Figure 1.

Targeted modification of the endoglin gene in ES cells. (A) Targeted replacement of mouse ENG (mENG) gene exons 4–8 with the corresponding human ENG (hENG) gene exons by homologous recombination in ES cells. The region drawn as a thick horizontal line represents the DNA used in the targeting vector. Mouse and human exons are shown as vertical closed and open boxes, respectively. EcoRV and KpnI restriction enzyme sites are indicated by arrow heads and arrows, respectively. Approximate location of PCR primers and Southern probes are also indicated. Primers used in these studies are shown in Supporting Information Table 1. (B) Four successfully targeted ES cell clones (i.e., 27, 40, 44 and 226) are identified by genomic PCR. Complete replacement events are confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion of the PCR product. (C) Genomic DNA from the ES cell clones are analyzed by Southern blot to confirm the result from genomic PCR. The chromosome karyotypes of clone 27 and 226 were examine by SKY imaging and found to be normal. These clones were individually microinjected into C57BL6/J blastocysts to obtain chimera mice. (D) Homozygous genetically engineered mice (GEMs) with novel human/mouse chimeric (humanized) ENG. The mice develop normally and are healthy without signs of telangiectasia.