Abstract

Context

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer amongst women but it has the highest survival rates amongst all cancer. Rehabilitation therapy of post-treatment effects from cancer and its treatment is needed to improve functioning and quality of life. This review investigated the range of methods for improving physical, psychosocial, occupational, and social wellbeing in women with breast cancer after receiving breast cancer surgery.

Method

A search for articles published in English between the years 2009 and 2014 was carried out using The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, PubMed, and ScienceDirect. Search terms included: ‘breast cancer’, ‘breast carcinoma’, ‘surgery’, ‘mastectomy’, ‘lumpectomy’, ‘breast conservation’, ‘axillary lymph node dissection’, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘therapy’, ‘physiotherapy’, ‘occupational therapy’, ‘psychological’, ‘psychosocial’, ‘psychotherapy’, ‘exercise’, ‘physical activity’, ‘cognitive’, ‘occupational’, ‘alternative’, ‘complementary’, and ‘systematic review’.

Study selection

Systematic reviews on the effectiveness of rehabilitation methods in improving post-operative physical, and psychological outcomes for breast cancer were selected. Sixteen articles met all the eligibility criteria and were included in the review.

Data extraction

Included review year, study aim, total number of participants included, and results.

Data synthesis

Evidence for exercise rehabilitation is predominantly in the improvement of shoulder mobility and limb strength. Inconclusive results exist for a range of rehabilitation methods (physical, psycho-education, nutritional, alternative-complementary methods) for addressing the domains of psychosocial, cognitive, and occupational outcomes.

Conclusion

There is good evidence for narrowly-focused exercise rehabilitation in improving physical outcome particularly for shoulder mobility and lymphedema. There were inconclusive results for methods to improve psychosocial, cognitive, and occupational outcomes. There were no reviews on broader performance areas and lifestyle factors to enable effective living after treatment. The review suggests that comprehensiveness and effectiveness of post-operative breast cancer rehabilitation should consider patients’ self-management approaches towards lifestyle redesign, and incorporate health promotion aspects, in light of the fact that breast cancer is now taking the form of a chronic illness with longer survivorship years.

Keywords: breast cancer surgery, rehabilitation methods, symptom-management, quality of life, lifestyle redesign, self-management

Introduction

Breast cancer incidences ranges from 19.3 per 100,000 women in Eastern Africa to 89.7 per 100,000 women in Western Europe and about 40 per 100,000 in developing countries.1 The 5-year relative survival rates for breast cancer in the US have improved dramatically from 63% in the 1960s to 90% in 2011.2 In Malaysia, the survival rates estimated in 2009 was 43.5%, with Malay, Chinese, and Indians, and Malays having 5-year survival rates of 39.7%, 48.2%, and 47.2% respectively, and the rates have also improved annually. The number of breast cancer survivors has increased dramatically as a result of early detection, better treatment, and various multidisciplinary rehabilitation methods.3,4 However, improved survival rate of breast cancers also comes with numerous side effects from the cancer and its treatment. There is a need for comprehensive rehabilitation methods to address the many impacts of the long-term effects of this treatment, including the less recognized cognitive impairments5 to improve survivors’ global functioning.

Surgery is usually conducted with the goal to completely remove breast tumors, either by mastectomy or lumpectomy, and to assess the status of the axillary lymph node, either through sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).6,7 Often, post-surgery rehabilitation focuses on the more obvious side effects, with pain and physical impairments being reported as the most debilitating complications after surgery. Therefore, commonly reported are upper body symptoms such as shoulder functions, breast/arm swelling (or lymphedema) with deformity, impairment of functionality, physical discomfort and numbness of the skin on upper arm and impaired arm.8–10 Reports from lymphedema studies showed it occurs in 10%–50% of women who underwent ALND and among 5%–20% of women who underwent SLNB.11 Post-operative, long-term pain has also been reported in 12%–50% of women with breast cancer, usually due to nerve injuries during surgery.12

Prevalence of cognitive impairment occurs in 10%–50% of women.7,13 It impacts on daily living performances (activities of daily living, work, and leisure tasks) and the overall quality of life (QoL), but is often ignored, partly because its cause cannot be identified. Furthermore, occupational outcomes, such as time needed to return to work, work absenteeism, and sick leave or employment status is also a concern of breast cancer survivors.14–16 Emotional distress caused by shifts in social support, and fear of recurrence and death has also impacted women’s wellbeing.17,18 However, the rehabilitation is less commonly reported and includes the less obvious psychosocial functioning, including anxiety and depression, and where esthetic deformity or affected body image have been implicated leading to poor coping strategies.19 As such, these after-effects from the post-operative procedures and adjuvant therapies can lead to a compromised QoL.20 Holistic rehabilitation including health-promotion and health-prevention strategies, and via early Occupational therapy involvements is warranted for effective living with breast cancer.

Description of intervention

Management of long-term side effects of breast cancer treatment is important to improve QoL of breast cancer survivors.21 Optimal rehabilitation includes the inputs from the various health professionals to help remediate and restore the impaired physical, psycho-social, and occupational functioning of women with breast cancer.22 Some of these methods include physical-therapy,23,24 exercise interventions,25,26 psychological therapies such as psycho-education,27,28 occupational therapy,29,30 nutritional rehabilitation,31 alternative rehabilitation such as yoga, music therapy,32,33 and complex rehabilitation.34

Aim

This review aims to examine systematic reviews on the rehabilitation methods for post-operative women with breast cancer, with a view on the comprehensiveness of these methods used, and if they consider breast cancer as a chronic illness. The findings may help inform suitable treatment decisions towards post-operative complications and the after-effects so that survivors can live for indefinite periods, with breast cancer taking a form of chronic illness.

Methods

Search terms

Systematic reviews were searched in four databases, restricted to full-text English language publications, which were published between January 2009 and October 2014, on adult women with breast cancer including The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, PubMed, and ScienceDirect.

The titles, abstracts, and keywords were searched for the following terms in order to identify the required articles: ‘breast cancer’, ‘breast carcinoma’, ‘surgery’, ‘rehabilitation’, ‘treatment’, ‘therapy’, ‘physical therapy’, ‘occupational therapy’, ‘psychological’, ‘psychosocial’, ‘exercise’, ‘physical activity’, ‘cognitive’, ‘occupational’, ‘alternative’, ‘complementary’, and ‘systematic review’. Search terms were identified by means of the inclusion and exclusion criteria specified in the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Study designs) table (Table 1). Boolean operators “AND”, and “OR” and search filter “asterisks (*)” were used together with the search terms to ensure all keyword variations were searched. Grey literature was excluded.

Table 1.

PICOS inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults aged 18 years and over Women with post-operation breast cancer |

Children and adolescents Participants involving men Co-morbidity physical (such as severe cardiac disease and hypertension) and psychiatric illnesses Women with metastatic cancer |

| Interventions | Physical and occupational therapy (eg, complex decongestive therapy, manual lymph drainage, standard physiotherapy, occupational therapy) Exercise (eg, exercise therapy, home based exercise routine, weight training) Psychosocial (eg, CBT, psycho-education) Alternative/complementary (eg, hypnotherapy, acupuncture, homeopathy, yoga) Nutritional (eg, dietary regime) Complex (eg, combination of psycho-education and nutrition etc rehabilitation) Reviews on pharmacological therapies and alternative medicine may be included if other rehabilitation methods mentioned above were also reviewed |

Pharmacological therapies Alternative medicine – eg, Chinese medicine herbal |

| Comparator (eg, control) | Systematic reviews of RCT interventions, cross-sectional studies, qualitative studies with or without control/comparison groups | None |

| Outcomes | Physical (eg, lymphedema, shoulder mobility) Psychosocial (eg, anxiety, depression, affect/mood, QoL) Occupational (eg, return to work, occupational gap, lifestyle) Cognition (eg, “chemo-brain”, cognitive functioning) |

None |

| Study design | Systematic reviews (systematic reviews of RCTs, non-randomized studies, cross-sectional, qualitative studies, etc) English language Dated from January 2009 to October 2014 |

Individual studies (RCTs, non-randomized studies, cross-sectional, qualitative, etc) Meta-analysis of studies Systematic reviews dated before January 2009 Systematic reviews with too few included studies (less than four included studies) Systematic reviews with too few databases searched (less than three electronic searches) |

Abbreviations: RCTs, randomized controlled trials; PICOS, Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Study designs; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; QoL, quality of life.

Selection of reviews

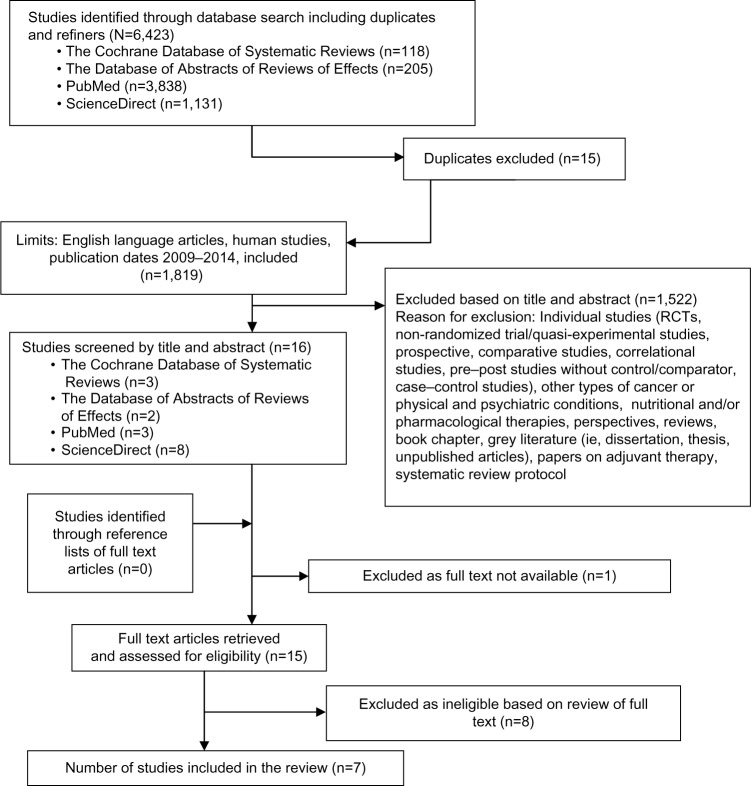

The electronic searches resulted in a number of studies uncovered from each database and was recorded immediately as shown in Figure 1. The online reference manager (EndNote) was used to remove any duplicates. Reviews were reviewed by one reviewer (ANM) to first assess their eligibility by reading the title and the abstract of each study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review process.

Abbreviation: RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

Participants

Systematic reviews which include a sample of post-surgery breast cancer adults (aged 18 years and over) were included. Reviews were excluded if the sample had other types of non-breast cancer.

Intervention

Systematic reviews on the effectiveness of single/combined (complex) rehabilitation eg, physical/occupational therapy, exercise, psychological, occupational, cognitive, nutrition, and alternative methods for post-operative breast cancer. The interventions included:

Physical therapy – complex decongestive therapy, manual lymph drainage (MLD), standard physiotherapy, occupational therapy etc.

Physical exercise – home based and instructed exercise.

Psychosocial – cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), psycho-education, etc.

Nutritional – change in dietary habits, dietary regime, etc.

Alternative – yoga, music therapy, acupuncture, etc.

Complex – combined interventions eg, counseling and exercise.

Types of studies

All published systematic reviews in the English language, on rehabilitation programs (for a combination of dysfunctions) were selected. The programs could have been physical or exercise or psychological or cognitive or occupational or nutritional or alternative or complex rehabilitation. There were no restrictions on the type of systematic review, ie, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), uncontrolled trials, non-randomized studies, qualitative, etc, provided that the aim of the study was to investigate the effects of either single or combinational rehabilitation methods/programs for post-operative patients with breast cancer. Systematic reviews were excluded if they focused on one narrow aspect or just one modality (eg, just specifically arm lymphedema as the outcome) and/or if there is less than four studies in the review paper, or it utilized less than three databases to search for individual studies.

Outcome measures

Systematic reviews on the physical, cognitive, occupational, and psychological outcomes in post-operative breast cancer patients were included:

Physical outcomes – shoulder mobility, lymphedema, wound healing, fatigue, etc.

Psychological outcomes – QoL, anxiety, depression, mood, and stress.

Cognitive outcomes – memory, attentiveness, “chemo-brain”, etc.

Occupational outcomes – return to work, absenteeism, etc.

Lifestyle redesign – preventive and health promotion methods.

Eligibility criteria

The present systematic review included published systematic review articles in the English language between the years 2009 and 2014. Unpublished reviews (grey literatures) were not included in the review. Inclusion criteria were kept relatively broad to ensure comprehensiveness in assessing the various rehabilitation methods reviewed in previous systematic reviews.

Data extraction and synthesis of results

Reviews were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria as depicted in the flow diagram (Figure 1). All relevant reviews accessed were followed-up to establish inclusion. The information extracted included data from the data extraction table (Table S1) guided by a previous systematic review of reviews.35 The data were extracted by one researcher (ANM) which was guided, assessed, and reviewed by a senior researcher (SYL). It was expected that there would be heterogeneity in the outcomes measured.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Methodological quality of included systematic reviews was independently rated according to the “assessment of multiple systematic reviews” (AMSTAR) tool.36 Responses of the AMSTAR tool are ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘can’t answer’, or ‘not applicable’, with yes being rated as ‘1’, and ‘no’, ‘can’t answer’, or ‘not applicable’ rated as ‘0’. Based on this scale, reviews were rated as ‘low’, ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ quality. The domains identified in the 11-item tool are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

A 11-item “assessment of multiple systematic reviews” (AMSTAR) for assessing systematic reviews

| The AMSTAR tool |

| 1. Was an “a priori” design provided? |

| 2. Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? |

| 3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? At least two electronic sources, include years and databases used (eg, Central, EMBASE, and MEDLINE). |

| 4. Was the status of publication (ie, grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? |

| 5. Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? |

| 6. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? |

| 7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? |

| 8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? |

| 9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? |

| 10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? |

| 11. Was the conflict of interest included? |

Results

Study selection

Figure 1 is the flow chart of the systematic review process from four databases (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, PubMed, and ScienceDirect), which yielded seven full-text systematic reviews,7,22,37–41 and excluded eight full-text reviews.8,42–48 Reasons for the exclusion of reviews are stated in the screening inclusion and exclusion table (Table S1).

Table 3 shows the AMSTAR tool for assessing methodological quality or rigor of each review included. Based on the AMSTAR tool, three out of the seven reviews reported were of good methodological quality,22,37,38 with three RCTs of medium quality,7,39,40 and one review of low quality.41 All but one systematic review41 had ensured at least two independent researchers had been involved in data extraction, or at least one researcher had checked the other’s work. All, but one review7 had ensured a comprehensive literature search (ie, a search strategy using more than two databases and one supplementary strategy that uses review of references in individual studies). Only one systematic review38 had searched for and attained unpublished or grey literature. Three reviews22,37,38 had ensured a list of included and excluded studies, with reasons for inclusion and exclusion provided. Methodological quality assessments of included studies were measured in all, but one review.41 However, only two reviews38,40 had considered the methodological quality of each individual study in carrying out a conclusion or recommendation of rehabilitation methods. All, but two reviews7,41 had assessed heterogeneity of included studies reviewed. Publication bias was assessed. In two reviews38,39 publication bias could not be assessed since the number of included studies was less than 20.

Table 3.

AMSTAR (assessment of multiple systematic reviews) checklist

| The AMSTAR Tool | Chan et al37 (2010) | McNeely et al38 (2010) | Paramanandam and Roberts39 (2014) | Fors et al40 (2011) | Hoving et al41 (2009) | Juvet et al22 (2009) | Selamat et al7 (2014) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was an “a priori” design provided? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | √ | √ |

| No | – | – | – | – | √ | – | – |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Was a comprehensive literature search performed? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | – |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | √ |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Was the status of publication (ie, grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? | |||||||

| Yes | – | √ | – | – | – | – | – |

| No | √ | – | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | – | – | – | √ | – |

| No | – | – | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | √ | √ |

| No | – | – | – | – | √ | – | – |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8. Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | |||||||

| Yes | – | √ | – | √ | – | √ | – |

| No | √ | – | √ | – | √ | – | √ |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9. Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | √ | – | √ | – |

| No | – | – | – | – | √ | – | √ |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10. Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | |||||||

| Yes | – | √ | √ | – | – | – | – |

| No | √ | – | – | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11. Was the conflict of interest included? | |||||||

| Yes | √ | √ | √ | – | √ | – | √ |

| No | – | – | – | √ | – | √ | – |

| Can’t answer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Not applicable | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Overall score | 8/11 | 11/11 | 7/11 | 7/11 | 4/11 | 8/11 | 5/11 |

| High quality | High quality | Moderate quality | Moderate quality | Low quality | High quality | Moderate quality | |

Characteristics of included reviews

A summary of the review is presented in Table 4, outlining its year of publication, aim, search strategy used, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number and design of included studies in each review, total number and age of participants, and outcomes measured.

Table 4.

Characteristics of systematic reviews on rehabilitation methods after breast cancer surgery

| No | Review, year | Type of rehabilitation method | Aim | Search strategy | Inclusion and exclusion criteria | No of studies included | Total number and age of participants | Assessed outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chan et al37 (2010) | Exercise | To review the efficacy of exercise programs on shoulder function and lymphedema in post-operative patients with breast cancer having ALND, as revealed by RCT. | Databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Ovid MEDLINE, the British Nursing Index, Proquest, ScienceDirect, PubMED, Scopus and the Cochrane Library Published articles between 2000 and 2009 Search terms: breast cancer, exercise, lymphoedema, shoulder mobility, randomized controlled trials. Limited to English language articles |

Inclusion: RCT, published in English. Intervention: various types of exercise programs – weight training, aerobic and strengthening exercises, stretching and range of motion (ROM) exercises. Outcome: range of shoulder motion, arm mobility, arm volume (at least one of these outcome variables). Exclusion: therapeutic intervention which only reported decongestive therapy involving MLD, compression garments and/or skin care, studies dealing with patients undergoing SLNB |

6 RCTs | 429 (range: 27–205); mean age of the participants was <60 years | Shoulder mobility and lymphedema: range of shoulder motion, shoulder mobility, arm circumference and arm volume |

| 2 | McNeely et al38 (2010) | Exercise | To examine the evidence of efficacy from RCTs involving exercise for preventing, minimizing and/or improving upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. | Databases: Cochrane Breast Cancer Group Specialised Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PEDro, LILACS No language restriction Search strategy: specified Published and unpublished up to 2008 |

Inclusion: adults: 17 years and older. Interventions – therapeutic exercise interventions for the upper-limb therapy program: 1) ROM exercises; 2) Passive ROM/manual stretching exercises; 3) Stretching exercises; 4) Strengthening or resistance exercises. Outcomes: upper-extremity ROM, muscular strength, lymphedema and pain, upper-extremity/shoulder function and QoL, early post-operative complications such as seroma formation, post-operative wound drainage, wound healing and effect modifiers such as adherence to exercise. | 24 RCTs | 2,132; mean age of participants ranged from 46.3 to 62.1 years | Primary outcomes: upper-extremity ROM, muscular strength, lymphedema and pain Secondary outcomes: upper-extremity/shoulder function (eg, reaching overhead, fastening a brassiere, doing a zipper up from behind) and QoL, early post-operative complications such as seroma formation, post-operative wound drainage, wound healing and effect modifiers such as adherence to exercise. |

| 3 | Paramanandam and Roberts39 (2014) | Weight training exercise | To investigate whether weight-training exercise intervention is harmful to women with or at risk of breast cancer related lymphedema. | Databases: PubMED, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, AMED, Cochrane, PEDro, SPORTDiscus and Web of Science. Search terms: specified Published after 2001–2012 |

Inclusion: Design – RCTs, peer reviewed, published in English after 2001. Population – women at risk of developing lymphedema. Intervention – weight-training exercises outcomes – lymphedema, strength, QoL, comparison – sham exercise, no-intervention control, only lower body exercises and education | 11 RCTs | 1,091; age of participants ranged from 49 to 57 years | Lymphedema onset or exacerbation, limb strength, QoL, BMI |

| 4 | Fors et al40 (2011) | Psychosocial | To determine the efficacy of psycho-education, CBT and social support interventions used in rehabilitation of breast cancer patients. | Databases: Cochrane Library, The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases, Medline, Embase, Cinahl, PsycINFO, AMED, PEDro Published articles between 1999 and 2008 Search terms: specified in Juvet et al22 (2009) |

Inclusion: RCTs investigating the effect of psychosocial rehabilitation with ≥20 female breast cancer Exclusion: low quality studies, less than 20 participants in each group, patients with metastatic cancer, data not presented separately for breast cancer and studies with other types of cancer |

18 RCTs | 3,272; N/A | QoL, fatigue, mood, health behavior, social functioning |

| 5 | Hoving et al41 (2009) | Occupational rehabilitation | To determine the effects of interventions on breast cancer survivors on return to work. | Databases: Ovid Medline, EMBASE, PsycInfo and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2006) Published articles between 1970 and 2007 Search term: specified |

Inclusion: types of studies: RCTs, cohort studies and observational studies, Interventions: all non-pharmacological interventions, types of outcome measures: work-related outcomes such as return to work, absenteeism, work disability, sick leave or employment status | 4 studies (1 controlled study, 3 uncontrolled studies) | 1,172; N/A | Return to work, absenteeism, work disability, sick leave or employment status |

| 6 | Juvet et al22 (2009) | Physical exercise, physiotherapy, psychosocial interventions, nutrition, complementary treatment, complex interventions | To assess the efficacy of single treatments and combination of treatments with respect to improvements in physical function and psychological wellbeing. | Databases: Cochrane Library, The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases, Medline, Embase, Cinahl, PsycINFO, AMED, PEDro Published articles up until 2008 Search term: specified |

Inclusion: study design: RCTs. Physical exercise, therapy, psychosocial interventions, nutritional complementary or complex interventions. Outcomes: somatic, psycho-social outcomes. Exclusion: low quality studies, studies with less than 20 per arm |

46 RCTs | 5,645; N/A | Outcomes: somatic, psychological, and social outcomes |

| 7 | Selamat et al7 (2014) | Cognitive rehabilitation | To review qualitative studies that explored the life/daily experiences of “chemo-brain” among breast cancer survivors, with particular attention given to the impact of “chemo-brain” on daily living and quality of life. | Databases: CINAHL, Web of Knowledge, EMBASE, Proquest, OVID SP, MEDLINE, Oxford Journal, ScienceDirect, PubMED, Wiley Published from 2002 to 2014. English language text Search terms: specified |

Inclusion: breast cancer and “chemo-brain”, qualitative study, studies published from 2002 to 2014, English publication. Exclusion: study design other than a qualitative design Methodology, studies with patients with cancers other than breast cancer, non-English papers |

7 qualitative studies | 193; N/A | Cognitive functioning or “chemo-brain”: Perception of “chemo-brain”, coping strategies towards cognitive dysfunction, self- management in being breast cancer survivor |

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; BMI, body mass index; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; CPT, mastectomy; MLD, manual lymph drainage; N/A, not assessed; QoL, quality of life; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Description of methods

The selected systematic reviews vary considerably in terms of the designs of the studies included, type of rehabilitation methods, and search strategy (databases used, publication years and language restriction, and search terms) (Table S2). Five out of the seven systematic reviews were RCTs.22,37–40 One review included both controlled and uncontrolled quantitative trials.41 Another study included qualitative studies only.7 Three reviews had specifically investigated physical rehabilitation methods: two papers were on the efficacy of various types of exercise,37,38 whilst one was on weight training exercises.39 One review investigated psychosocial interventions,40 another the efficacy of occupational rehabilitation on women with breast cancer,41 and one explored cognitive functioning.7 Only the review by Juvet et al22 covered a holistic range of rehabilitation methods – physical activity rehabilitation, psychosocial rehabilitation, nutritional rehabilitation, complementary or alternative rehabilitation (ie, yoga, music therapy, etc), and complex (psycho-education plus counseling) rehabilitation for women after breast cancer.22

For each of the resulted review, we had searched in more than one database for individual studies (refer to Table 4). Restriction of publication years and language varied across the seven reviews. Chan et al37 included published articles between the years 2000 and 2009. Paramanandam and Roberts39 restricted review to articles dated between 2001 and 2012, Fors et al40 included published articles between the years 1999 and 2008, Hoving et al41 included articles between the years of 1970 and 2007, Juvet et al22 included published articles up until 2008, and Selamat et al7 included articles restricted to those published from 2002 to 2014. One review38 included both published and unpublished literature until 2008. Three reviews7,37,39 restricted articles to the English language only. One review38 did not have any language restrictions. Three reviews22,40,41 did not specify language restrictions. All reviews specified the various search terms used.

Description of participants

The total number of participants was specified in all seven reviews. The age of participants was specified in three reviews37–39 only. Details of the total number and age of participants are provided in Table 4. All but three reviews38,39,41 specified exclusion criteria for participants. Chan et al37 excluded reviews which included male participants.

Description of outcomes

Physical, psychosocial, occupational, and cognitive outcomes varied. Amongst the physical outcomes assessed were: upper body symptoms (ie, shoulder function, arm movement, limb strength),37,38 risk or incidence of secondary lymphedema,37–39 fatigue,40 pain,38 seroma formation,38 wound drainage,38 physical fitness (ie, body mass index [BMI], body composition),22,39 and adherence to exercise.38 Amongst the psychosocial outcomes were QoL,38–40 mood, health behavior, and social function.40 Occupational outcomes included return to work, absenteeism, work disability, sick leave or employment status measured by only one systematic review.41 Cognitive outcomes include perception of “chemo-brain”, coping strategies towards cognitive dysfunction, and self-management as breast cancer survivor. Only one review22 had attempted to look at somatic, psychological, and social outcomes as a comprehensive whole.

Findings

Effects on physical outcomes

Table 5 shows the results of the effects of various rehabilitation methods on physical outcomes. Five reviews had investigated the effects of rehabilitation for physical outcomes, with adequate methodological quality: three reviews were rated as having high methodological quality,22,37,38 and two were rated as having medium quality.39,40

Table 5.

Results of studies on rehabilitation methods on physical outcomes

| Chan et al37 (2010) | McNeely et al38 (2010) | Paramanandam and Roberts39 (2014) | Fors et al40 (2011) | Juvet et al22 (2009) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||||

| Upper body symptoms | Exercise: shoulder movement – overall improvement in shoulder mobility, irrespective of time period of implementation. However, most exercise programs were implemented soon after operation. Improvement in flexion and abduction movement measurements of the shoulder joint was significantly better in treatment groups. Most studies had used a goniometer to measure range of motion. | Exercise: shoulder movement – delayed versus early – (ten studies). Early exercise was more effective than delayed in the short-term recovery of shoulder flexion ROM. Structured exercise versus usual care (14 studies) – six were post-operative, three during adjuvant treatment and five following cancer treatment. Structured exercise programs in the post-operative period improved shoulder flexion ROM in the short-term and yielded additional benefit for shoulder function post-intervention and at 6-month follow-up. | Exercise: weight training exercise – limb strength of low to moderate intensity with relatively slow progression improved the upper limb strength and lower limb strength | – | Physiotherapy: shoulder movement – of the seven RCTs examining the effect of physiotherapy, three investigated shoulder function. Shoulder mobility improved after physiotherapy, but results were influenced by type of surgery (ie, BCT or MRM). There is a lack of high quality studies to guide conclusion on the effect of physiotherapy interventions to improve shoulder function after breast cancer surgery. Complex intervention: shoulder movement – inconclusive results. Only one study (psycho-education and exercise) investigated effect on shoulder mobility (ROM) with improvements found in the intervention group. Arm movement – inconclusive results |

| Lymphedema | Exercise: no significant change in incidence of lymphedema in studies involving upper limb exercise. Mean change in arm circumferences in different positions ranged from 0.10 to 0.30 cm, which was not significant. There was minimal difference in arm volume. In two studies a difference of only 0.70 and 2 mL was noted between groups. | Exercise: structured exercise versus usual care – there was no evidence of increased risk of lymphedema from exercise at any time point. | Exercise: weight training exercise of low to moderate intensity with relatively slow progression does not increase arm volume or incidence of lymphedema | – | Physiotherapy: inconclusive results (lack of high quality studies). Of the seven RCTs examining physiotherapy, four studied the effects on arm lymphedema. MLD (three studies) – no significant benefit of MLD. One study showed a decrease in lymphedema with complex decongestive therapy (lymph drainage, compression bandage, evaluation, medical exercise, and skin care) compared to SLNB. Three studies showed that effect of physiotherapy is not influenced by timing. Six studies are done after ALND and not after SLNB, while one study was done in mixed ALND and SLNB population Exercise: moderate level of evidence. Three studies showed that early exercise was not associated with aggravated lymphedema |

| Wound healing | – | Exercise: delayed versus early – early exercise resulted in significant increase in wound drainage volume. | – | – | – |

| Body composition | – | – | Exercise: weight training exercise of low to moderate intensity with relatively slow progression – no significant effects for BMI | – | Exercise: inconclusive results for BMI Nutrition: two RCTs. Inconclusive results on body weight Complex: inconclusive results on body composition |

| Fatigue | – | – | – | Psycho-education: overall significant short-term benefit for fatigue was observed CBT – inconclusive results. Modest short-term benefit on fatigue was found in one study reviewed | Exercise: inconclusive results. Three studies showed that exercise after primary treatment may reduce fatigue. Exercise intervention during primary cancer treatment showed varied result. Psycho-education: inconclusive results. CBT: inconclusive results. Social and emotional support intervention: inconclusive results |

| Hot flashes | – | – | – | – | Complementary/alternative rehabilitation: inconclusive results. Incidence of hot flashes was addressed in two studies, relaxation training intervention reduced the incidence, while acupuncture also reduced but did not reach statistical significance |

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; BCT, breast conservative therapy; BMI, body mass index; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; MRM, modified radical mastectomy; MLD, manual lymph drainage; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; ROM, range of motion; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Exercise rehabilitation showed significant improvement in shoulder movement – irrespective of type or time period of implementation37 but, early exercise was found to be more effective than delayed exercise.38 Paramanandam and Roberts39 found that gradual intensity weight training, with slow progression, improved upper and lower limb strength. More importantly, exercise did not increase risk or change in the incidence rate of lymphedema22,37–39 and complex decongestive therapy decreased the incidence of lymphedema as compared to standard physiotherapy.22 The benefits of exercise were well reported. Early exercise (versus delayed) also helps wound healing by increasing the wound drainage volume.38 There were inconclusive results for exercise interventions on BMI.22,39 With fatigue management, psycho-education had a significant short-term benefit,40 but not cognitive behavioral therapy.22,40 With hot flashes, complementary rehabilitation (acupuncture, yoga, art therapy, or relaxation training) did not show conclusive evidence.22 Overall, the physical rehabilitation seems to focus on shoulder range of motion, fatigue, body weight, wound, and hot flashes amongst the wide range of after-effects from breast cancer and its treatment.

Effects on non-physical related outcomes

Table 6 shows the effects of rehabilitation methods on less obvious psychological, occupational, and cognitive outcomes. Of the five reviews, the methodological quality of the three reviews was rated as high quality,22,37,38 and two reviews39,40 were rated as medium quality.

Table 6.

Results of studies on rehabilitation methods on psychosocial, occupational, and cognitive outcomes

| Paramanandam and Roberts39 (2014) | Fors et al40 (2011) | Hoving et al41 (2009) | Juvet et al22 (2009) | Selamat et al7 (2011) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||||

| Psychosocial: quality of life | Exercise: weight training exercise of low to moderate intensity with relatively slow progression. Inconclusive results. Some aspects of QoL may improve with weight training. | Psycho-education: inconclusive results. No significant increase in QoL. Three RCTs on effect of the interventions during and another three on effects after primary treatment CBT: seven trials on CBT, four on after versus three during primary treatment. Overall significant short-term increase in QoL. Social and emotional support interventions: inconclusive impact (five studies). |

– | Exercise: moderate level of evidence (ten studies). Four studies showed that exercise after primary treatment may improve short-term QoL. Psycho-education: six RCTs on psycho-educational. Inconclusive results. CBT: seven RCTs examined CBT. Inconclusive results. Social and emotional support – five studies. Inconclusive results. Complementary: five studies. Small effect on the QoL. |

– |

| Psychosocial: health behaviors | – | Inconclusive results for all types of interventions | – | CBT: inconclusive results Social and emotional support intervention: inconclusive results |

– |

| Psychosocial: social function and coping | – | Inconclusive results for all types of interventions | – | Social and emotional support intervention: inconclusive results Complementary: inconclusive results |

– |

| Psychosocial: mood | – | Psycho-education: inconclusive results CBT: inconclusive results on mood. Social and emotional support: inconclusive results. Improvement seen on the POMS scale, but not on HADS and MAC scales |

– | Exercise: inconclusive results. Psycho-education: inconclusive results. CBT: inconclusive results. Improved mood – three CBT studies measured mood (anxiety, event related distress and depression) Social and emotional support – inconclusive results Complementary rehabilitation: small effect on mood outcomes |

– |

| Cognitive: cognitive dysfunction | – | – | – | – | Five studies on self-management rehabilitation. Psychosocial interventions and practical reminders were good coping strategies. With cultural differences in coping strategies Asians are more likely to use complementary medicine |

| Occupational: return to work | – | – | Inconclusive results – counseling or exercise – as three studies had no comparison group. Longer time needed to return to work was related to more extensive surgical procedures. | – | – |

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MAC, the Mental Adjustment to Cancer; POMS, Profile of Mood States; QoL, quality of life; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

QoL was assessed in three reviews22,39,40 as an outcome of exercise rehabilitation,22,39 CBT,40 and psycho-education22,40 albeit with inconclusive results. One review22 found inconclusive results on the benefit of both complementary and complex decongestive therapy on QoL. Health behaviors and social function and coping were assessed in two reviews22,40 with inconclusive results. There were inconclusive results of social and emotional support interventions in two reviews.22,40 Mood outcomes such as anxiety, event related distress, and depression assessed in two reviews22,40 found that psycho-education, CBT, and social and emotional support interventions yield inconclusive results towards improving mood. There was some evidence that complementary intervention after primary breast cancer treatment was found to have a small effect on mood outcomes.22

Rehabilitation methods for cognitive outcomes

Cognitive outcomes were measured in one review only.7 Psychosocial interventions and practical reminders were adequate coping strategies towards cognitive dysfunction but the meta-ethnography review also found cultural differences in coping strategies, such as Asian women being more likely to use complementary medicine like medicinal herbs, to improve cognitive functioning.

Rehabilitation methods on occupational outcomes

There were inconclusive outcomes with occupational rehabilitation41 – whether rehabilitation consisting of counseling or exercise would indeed decrease time needed to return to work in breast cancer survivors. However, the review showed that the extensiveness of the surgical procedures correlates with the length of time needed to return to work.

Discussion

An over-emphasis on physical dysfunction

Effectiveness of rehabilitation methods on physical, psychosocial, cognitive, and occupational outcomes vary according to numerous type/s of rehabilitation methods used. Reviews investigating physical outcomes dominate the literatures. There were relatively less systematic reviews on cognitive outcomes and occupational outcomes, both were reviewed by Selamat et al7 and Hoving et al41 respectively and both suggests a lack of work and acknowledgment by health professionals and survivors in this area of cognitive impairment. Exercise was found to be effective in improving shoulder mobility, limb strength, and wound healing, although it was found to be inconclusive for fatigue and body composition (ie, BMI) management, and lymphedema. In fact with the common fatigue post operation, more work is needed as there were inconclusive findings for psycho-education, CBT, and social-emotional rehabilitation for fatigue management. There were also inconclusive results for the efficacy of complementary rehabilitation (acupuncture, yoga, art therapy, or relaxation training) on hot flashes.

Overall, exercise seems to be the one rehabilitation method to improve the narrow physical outcomes eg, for shoulder mobility, and irrespective of the type of exercise implemented. The benefit of broader exercise such as exercise for lifestyle redesign for a preventive stance against cancer recurrence and for better QoL, needs more research. There are some studies, both quantitative and qualitative49,50 which have highlighted barriers to exercise 5 years after diagnosis of breast cancer and uncovered many expressed psychological barriers (eg, low motivation, dislike of gym), environmental barriers (eg, employment-priority, low access to facilities, interfering seasonal weather, traffic congestion to get to the gym), and lack of time. As such, studies are also needed on interventions to overcome these barriers to exercise and to ensure adherence to exercise regimes to gain its benefit on cancer recurrences and for better quality of living during the survivorship phases.

A lack of evidence for non-physical rehabilitation methods

Reviews showed inconclusive results were found for the efficacy of rehabilitation methods using psycho-education, CBT, social-emotional support, complementary-alternative methods towards improving health behaviors and/or QoL. In general, the review of the reviews also found inconclusive results on social functioning, coping, and mood outcomes. However, complementary intervention may have a small effect on mood outcomes. Nevertheless, the studies are largely heterogeneous in terms of type, length, and components of rehabilitation methods which make the comparisons rather difficult to carry out.

For less recognized problems faced by survivors of breast cancer, qualitative research identified “chemo-brain”, and attitudinal changes towards work.7,51 Psycho-social rehabilitation and practical reminders were strategies proposed to improve cognitive function despite variations due to cultural differences. With occupational rehabilitation, inconclusive results were found on whether exercise or counseling rehabilitation would decrease time needed to return to work in women with breast cancer.41 Qualitative findings from focus groups of multi-ethnic survivors have highlighted several barriers such as fear of environmental hazards, high job-demand, intrusive thoughts and family over-protectiveness,30 as well as other socio-demographic factors eg, education, range of treatment received, strenuous physical work, fatigue, and psychological factors such as negative mood.52 Future occupational studies should investigate the breadth and depth of rehabilitation methods (eg, work stamina, tolerance, psychological factors for facilitating work re-entry, work accommodations such as flexibility towards work hours etc) for enabling post-operation survivors to return to work in a design that has a control or comparison group (ie, other types of interventions, wait-list, etc).

A need for more comprehensive methods to enable living for indefinite period

Overall, the lack of evidence for non-physical rehabilitation methods highlight the lack of research work that extend beyond the rehabilitation methods for physical after-effects. The gradual acknowledgment that breast cancer is taking a form of chronic illness53 is not proportionate to the current rehabilitation methods which suggest an overall management of breast cancer as an acute/fatal condition. Amongst the important implications of this current review is that rehabilitation for women with breast cancer should be comprehensive (ie, broader rather than eg, narrowly focused on upper limb function) and proactive (rather than reactive). This stance is a better preparation of breast cancer survivors to live indefinitely with the condition and to empower them to re-engage in lifestyle modification and/or lifestyle redesign,54 in order to address ill-health, and improve their wellbeing, lifespan, and QoL. The specific, but predominantly performance component rehabilitation, such as improving shoulder mobility, is effective but not sufficient to enable or inform survivors to live the best they can for the remainder of their life span. The lack of emphasis on patient self-management and occupational redesign towards a healthier lifestyle suggests a dire lack of focus on these broader aspects of life. This also showed a lack of appreciation that breast cancer is evolving into a form of chronic disease requiring a brand new platform to support its increasing numbers of survivors.

Limitations

The main limitation of this systematic review on systematic reviews is the difficulty to synthesize because of the heterogeneous nature of the methodology of each review. There were varying inclusion-exclusion criteria, different outcome measures, which leads to difficulties extracting and synthesizing the data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current rehabilitation methods tend to focus narrowly on performance components (particularly on physical impairments or dysfunctions). The review found evidence that exercise rehabilitation methods improves physical outcome post operation, although, inconclusive results exist on rehabilitation methods to improve the non-physical sequelae such as psychosocial, cognitive, occupational, and broader lifestyle performance factors. Clearly missing are the rehabilitation methods to enable survivors to redesign their lifestyle in tandem with living with a breast cancer condition that is taking a form of chronic disease. This calls for health prevention and illness prevention lifestyle strategies to i) control cancer recurrence and ii) to promote better QoL during the indefinite period of survivorship. With the overwhelming strong evidence that cancer risk is affected by lifestyle, future studies with higher methodological rigor should be conducted on health promotion strategies to enable healthy lifestyle.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

Screening inclusion/exclusion table

| Study reference | Dated 2009–2014? | Exercise, physiotherapy, psychosocial, nutrition or alternative rehabilitation? | Published systematic review in English? | Review include adult breast cancer survivors after surgery? | Four included studies or more per systematic review? | More than two databases searched? | Non-metastatic, no physical co-morbidity? | Measure more than one component of physical, psycho-social, cognitive, or occupational outcomes? | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40. Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, et al. Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes (include) |

| 41. Hoving JL, Broekhuizen ML, Frings-Dresen MH. Return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of intervention studies. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 22. Juvet LK, Elvsaas IK, Leivseth G, et al. Rehabilitation of breast cancer patients. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 38. McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, et al. Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 39. Paramanandam VS, Roberts, D Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lympho-edema: a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 7. Selamat MH, Loh SY, Mackenzie L, Vardy J. Chemobrain Experienced by Breast Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Ethnography Study Investigating Research and Care Implications. PloS one, 9(9), e108002. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 37. Chan DN, Lui LY, So WK. Effectiveness of exercise programmes on shoulder mobility and lympho-edema after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer: systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 42. E Lima MT, E Lima JG, de Andrade MF, Bergmann A. Low-level laser therapy in secondary lymphedema after breast cancer: systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No (exclude) |

| 43. Huang TW, Tseng SH, Lin CC, et al. Effects of manual lymphatic drainage on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 44. Johannsen M, Farver I, Beck N, Zachariae R. The efficacy of psychosocial intervention for pain in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 45. Khan F, Amatya B, Ng L, Demetrios M, Zhang NY, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for follow-up of women treated for breast cancer. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 46. Markes M. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy of breast-cancer: a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 47. Moseley AL, Carati CJ, Piller NB. A systematic review of common conservative therapies for arm lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer treatment. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 48. Shamley DR, Barker K, Simonite V, Beardshaw A. Delayed versus immediate exercises following surgery for breast cancer: a systematic review. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 8. Chung C, Lee S, Hwang S, Park E. Systematic Review of Exercise Effects on Health Outcomes in Women with Breast Cancer. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | No |

Notes: Excluded – if “nil/no” for any one. Included – if “yes” for all.

Table S2.

Search strategy

| The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Surgery |

| 03. Rehabilitation |

| 04. Therapy |

| 05. 01 and 02 |

| 06. 03 or 04 |

| 07. 05 and 06 |

| ScienceDirect (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Breast carcinoma |

| 03. Surgery |

| 04. Mastectomy |

| 05. MRM |

| 06. Lumpectomy |

| 07. Breast conservation |

| 08. Axillary lymph node dissection |

| 09. ALND |

| 10. Rehabilitation |

| 11. Treatment |

| 12. Physiotherapy |

| 13. Psychological |

| 14. Psychosocial |

| 15. Psychotherapy |

| 16. Exercise |

| 17. Physical activity |

| 18. Cognitive |

| 19. Occupational |

| 20. Alternative |

| 21. Complementary |

| 22. Systematic Review |

| 23. 1 or 2 |

| 24. 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 |

| 25. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 26. 22 |

| 27. 23 and 24 and 25 and 26 |

| PubMed (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Breast carcinoma |

| 03. Surgery |

| 04. Mastectomy |

| 05. MRM |

| 06. Lumpectomy |

| 07. Breast conservation |

| 08. Axillary lymph node dissection |

| 09. ALND |

| 10. Rehabilitation |

| 11. Treatment |

| 12. Physiotherapy |

| 13. Psychological |

| 14. Psychosocial |

| 15. Psychotherapy |

| 16. Exercise |

| 17. Physical activity |

| 18. Cognitive |

| 19. Occupational |

| 20. Alternative |

| 21. Complementary |

| 22. Systematic Review |

| 23. 1 or 2 |

| 24. 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 |

| 25. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 26. 22 |

| 27. 23 and 24 and 25 and 26 |

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; MRM, modified radical mastectomy.

Acknowledgments

English language checked by Dr Gail Boniface, Cardiff University, United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.cancer.org [homepage on the Internet] American Cancer Society Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; [Accessed January 31, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marín ÁP, Sánchez AR, Arranz EE, Auñón PZ, Barón MG. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer and cognitive impairment. South Med J. 2009;102(9):929–934. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181b23bf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meade E, Dowling M. Early breast cancer: diagnosis, treatment and survivorship. Br J Nurs. 2012;21(17):S4–S8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.Sup17.S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selamat MH, Loh SY, Mackenzie L, Vardy J. Chemobrain Experienced by Breast Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Ethnography Study Investigating Research and Care Implications. PloS One. 2014;9(9):e108002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a ran-domized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung C, Lee S, Hwang S, Park E. Systematic Review of Exercise Effects on Health Outcomes in Women with Breast Cancer. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2013;7(3):149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes SC, Johansson K, Stout NL, et al. Upper-body morbidity after breast cancer: incidence and evidence for evaluation, prevention, and management within a prospective surveillance model of care. Cancer. 2012;118(8 Suppl):2237–2249. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosompra K, Ashikaga T, Obrien PJ, Nelson L, Skelly J. Swelling, numbness, pain, and their relationship to arm function among breast cancer survivors: a disablement process model perspective. Breast J. 2002;8(6):338–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106(1):4–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rietman JS, Dijkstra PU, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Late morbidity after treatment of breast cancer in relation to daily activities and quality of life: a systematic review. Eur J Surgical Oncol. 2003;29(3):229–238. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault R, Buzdar AU, Cruickshank S, Meyers CA. ‘Chemobrain’ in breast carcinoma?: a prologue. Cancer. 2004;101(3):466–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer survival, work, and earnings. J Health Econ. 2002;21(5):757–779. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Bednarek HL, Schenk M. Short-term effects of breast cancer on labor market attachment: results from a longitudinal study. J Health Econs. 2005;24(1):137–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm ML. Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(5):914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrow GR, Roscoe JA, Hickok JT, Andrews PL, Matteson S. Nausea and emesis: evidence for a biobehavioral perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10(2):96–105. doi: 10.1007/s005200100294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychol. 1999;18(2):159–168. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van’t Spijker A, Trijsburg RW, Duivenvoorden H. Psychological sequelae of cancer diagnosis: a meta-analytic review of 58 studies after 1980. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(3):280–293. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu MR, Chen CM, Haber J, Guth AA, Axelrod D. The effect of providing information about lymphedema on the cognitive and symptom outcomes of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(7):1847–1853. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki M, Yoshikawa E, Matsuoka Y, et al. Smaller regional volumes of brain gray and white matter demonstrated in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2007;109(1):146–156. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juvet LK, Elvsaas I, Leivseth G, et al. Rehabilitation of breast cancer patients. Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services. 2009;2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torres Lacomba M, Yuste Sánchez MJ, Zapico Goñi Á, et al. Effectiveness of early physiotherapy to prevent lympho-edema after surgery for breast cancer: randomised, single blinded, clinical trial. BMJ. 2010;340:b5396. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beurskens CH, van Uden CJ, Strobbe LJ, Oostendorp RA, Wobbes T. The efficacy of physiotherapy upon shoulder function following axillary dissection in breast cancer, a randomized controlled study. BMC Cancer. 2007;7(166) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer–related lymphedema. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):664–673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4396–4404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1143–1152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman AE, Tulman L, Samarel N, et al. The effect of telephone social support and education on adaptation to breast cancer during the year following diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(4):822–829. doi: 10.1188/05.onf.822-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loh SY, Yip CH, Packer T, Quek KF. Self-management pilot study on women with breast cancer: lessons learnt in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(5):1293–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan FL, Loh SY, Su T, Veloo VW, Ng LL. Return to work in multi-ethnic breast cancer survivors-a qualitative inquiry. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(11):5791–5797. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackburn GL, Wang KA. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):s878–s881. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.878S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou K, Li X, Li J, et al. A clinical randomized controlled trial of music therapy and progressive muscle relaxation training in female breast cancer patients after radical mastectomy: Results on depression, anxiety and length of hospital stay. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014:pii:S1462-3889(14)00106-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee B, Vadiraj HS, Ram A, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga program in modulating psychological stress and radiation-induced geno-toxic stress in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):242–250. doi: 10.1177/1534735407306214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demark-Wahnefried W, Case LD, Blackwell K, et al. Results of a diet/exercise feasibility trial to prevent adverse body composition change in breast cancer patients on adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8(1):70–79. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Higgins S. A systematic review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of randomised trials of interventions for preventing and treating preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;142(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan DN, Lui LY, So WK. Effectiveness of exercise programmes on shoulder mobility and lymphoedema after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1902–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, et al. Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD005211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paramanandam VS, Roberts D. Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2014;60(3):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, et al. Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(9):909–918. doi: 10.1002/pon.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoving JL, Broekhuizen MLA, Frings-Dresen MH. Return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.E Lima MT, E Lima JG, de Andrade MF, Bergmann A. Low-level laser therapy in secondary lymphedema after breast cancer: systematic review. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(3):1289–1295. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1240-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang TW, Tseng SH, Lin CC, et al. Effects of manual lymphatic drainage on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johannsen M, Farver I, Beck N, Zachariae R. The efficacy of psychosocial intervention for pain in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):675–690. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan F, Amatya B, Ng L, Demetrios M, Zhang NY, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for follow-up of women treated for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD009553. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009553.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Markes M. Exercise for Women Receiving Adjuvant Therapy of Breast-Cancer: A Systematic Review. [doctoral dissertation] Technical University of Berlin; Berlin, Germany: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moseley AL, Piller NB, Carati CJ. The effect of gentle arm exercise and deep breathing on secondary arm lymphedema. Lymphology. 2005;38(3):136–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shamley DR, Barker K, Simonite V, Beardshaw A. Delayed versus immediate exercises following surgery for breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;90(3):263–271. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-4727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hefferon K, Murphy H, McLeod J, Mutrie N, Campbell A. Understanding barriers to exercise implementation 5-year post-breast cancer diagnosis: a large-scale qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(5):843–856. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loh SY, Chew SL, Quek KF. Physical activity engagement after breast cancer: Advancing the health of survivors. Health. 2013;5:838–846. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kennedy F, Haslam C, Munir F, Pryce J. Returning to work following cancer: a qualitative exploratory study into the experience of returning to work following cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16(1):17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loh SY, Yip CH. Breast cancer as a chronic illness: implications for rehabilitation and medical education. Journal of the University of Malaya Medical Centre. 2006;9(2):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JE, Loh SY. Physical Activity and Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors: A Lack of Focus for Lifestyle Redesign. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(4):2551–2555. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Screening inclusion/exclusion table

| Study reference | Dated 2009–2014? | Exercise, physiotherapy, psychosocial, nutrition or alternative rehabilitation? | Published systematic review in English? | Review include adult breast cancer survivors after surgery? | Four included studies or more per systematic review? | More than two databases searched? | Non-metastatic, no physical co-morbidity? | Measure more than one component of physical, psycho-social, cognitive, or occupational outcomes? | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40. Fors EA, Bertheussen GF, Thune I, et al. Psychosocial interventions as part of breast cancer rehabilitation programs? Results from a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes (include) |

| 41. Hoving JL, Broekhuizen ML, Frings-Dresen MH. Return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of intervention studies. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 22. Juvet LK, Elvsaas IK, Leivseth G, et al. Rehabilitation of breast cancer patients. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 38. McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, et al. Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 39. Paramanandam VS, Roberts, D Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lympho-edema: a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 7. Selamat MH, Loh SY, Mackenzie L, Vardy J. Chemobrain Experienced by Breast Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Ethnography Study Investigating Research and Care Implications. PloS one, 9(9), e108002. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 37. Chan DN, Lui LY, So WK. Effectiveness of exercise programmes on shoulder mobility and lympho-edema after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer: systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| 42. E Lima MT, E Lima JG, de Andrade MF, Bergmann A. Low-level laser therapy in secondary lymphedema after breast cancer: systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No (exclude) |

| 43. Huang TW, Tseng SH, Lin CC, et al. Effects of manual lymphatic drainage on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 44. Johannsen M, Farver I, Beck N, Zachariae R. The efficacy of psychosocial intervention for pain in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 45. Khan F, Amatya B, Ng L, Demetrios M, Zhang NY, Turner-Stokes L. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for follow-up of women treated for breast cancer. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 46. Markes M. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy of breast-cancer: a systematic review. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 47. Moseley AL, Carati CJ, Piller NB. A systematic review of common conservative therapies for arm lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer treatment. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 48. Shamley DR, Barker K, Simonite V, Beardshaw A. Delayed versus immediate exercises following surgery for breast cancer: a systematic review. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No |

| 8. Chung C, Lee S, Hwang S, Park E. Systematic Review of Exercise Effects on Health Outcomes in Women with Breast Cancer. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | No |

Notes: Excluded – if “nil/no” for any one. Included – if “yes” for all.

Table S2.

Search strategy

| The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Surgery |

| 03. Rehabilitation |

| 04. Therapy |

| 05. 01 and 02 |

| 06. 03 or 04 |

| 07. 05 and 06 |

| ScienceDirect (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Breast carcinoma |

| 03. Surgery |

| 04. Mastectomy |

| 05. MRM |

| 06. Lumpectomy |

| 07. Breast conservation |

| 08. Axillary lymph node dissection |

| 09. ALND |

| 10. Rehabilitation |

| 11. Treatment |

| 12. Physiotherapy |

| 13. Psychological |

| 14. Psychosocial |

| 15. Psychotherapy |

| 16. Exercise |

| 17. Physical activity |

| 18. Cognitive |

| 19. Occupational |

| 20. Alternative |

| 21. Complementary |

| 22. Systematic Review |

| 23. 1 or 2 |

| 24. 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 |

| 25. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 26. 22 |

| 27. 23 and 24 and 25 and 26 |

| PubMed (2009–2014) |

| 01. Breast cancer |

| 02. Breast carcinoma |

| 03. Surgery |

| 04. Mastectomy |

| 05. MRM |

| 06. Lumpectomy |

| 07. Breast conservation |

| 08. Axillary lymph node dissection |

| 09. ALND |

| 10. Rehabilitation |

| 11. Treatment |

| 12. Physiotherapy |

| 13. Psychological |

| 14. Psychosocial |

| 15. Psychotherapy |

| 16. Exercise |

| 17. Physical activity |

| 18. Cognitive |

| 19. Occupational |

| 20. Alternative |

| 21. Complementary |

| 22. Systematic Review |

| 23. 1 or 2 |

| 24. 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 |

| 25. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 |

| 26. 22 |

| 27. 23 and 24 and 25 and 26 |

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; MRM, modified radical mastectomy.