Abstract

Background

Little is known about the perceived causes of stress and what strategies African-American men use to promote resiliency. Participatory research approaches are recommended as an approach to engage minority communities. A key goal of participatory research is to shift the locus of control to community partners.

Objective

To understand perceived sources of stress and tools used to promote resiliency in African American men in South Los Angeles.

Methods

Our study utilized a community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) approach to collect and analyze open-ended responses from 295 African American men recruited at a local, cultural festival in Los Angeles using thematic analysis and the Levels of Racism framework.

Results

Almost all (93.2%) men reported stress. Of those reporting stress, 60.8% reported finances and money and 43.2% reported racism as a specific cause. Over 60% (63.4%) reported that they perceived available sources of help to deal with stress. Of those noting a specific source of help for stress (n=76), 42.1% identified religious faith. Almost all of the participants (92.1%) mentioned specific sources of resiliency such as religion and family.

Conclusions

Stress due to psycho-social factors such as finances and racism are common in African American men. But at the same time, most men found support for resiliency to ameliorate stress in religion and family. Future work to engage African-American men around alleviating stress and supporting resiliency should both take into account the perceived causes of stress and incorporate culturally appropriate sources of resiliency support.

INTRODUCTION

An important goal of participatory research is to shift the locus of control to and increase capacity for research in under-resourced communities.1,2 This paper describes the background, rationale and findings of a study designed and implemented by Healthy African-American Families II (HAAFII), a grassroots health advocacy agency in South Los Angeles. As part of a strategy to build research capacity and to demonstrate the value of community knowledge in health research, HAAFII designed a study and collected data on stress and resilience in African-American men, while partnering with researchers for analysis and manuscript development.

African-American men are at high risk for adverse health and mental health outcomes relative to other ethnicities. They are less likely to have health insurance, to utilize health services when insured, and at greater risk of receiving lower quality care when seeking services, than men from other racial groups. Moreover, their life expectancy is as much as 5.4 years lower.3-6 A critical factor in this mortality epidemic may be the disproportionate stress African-American men experience in their daily lives from the social determinants of health, including unemployment, poverty, and discrimination.7-9 Community participants from an earlier study reported perceptions of neighborhood stressors (e.g., noise, decaying buildings, and community violence), economic factors (e.g., poverty and unemployment) and racial discrimination as significant causes of “stress and drama,” with a detrimental impact on perceived physical and emotional well-being.10,11 In another recent study in Los Angeles, 25% of African-American men screened tested positive for depression, one common mental health outcome of exposure to stress.12 Although a number of studies have examined the relationship between stress and health outcomes in African-American men, we are not aware of studies using a community-developed design. 9, 12-28

APPROACH

HAAFII is a 501c3 organization founded by community members in 1992 with minimal resources but intense commitment29 to eliminate racial disparities in health outcomes in South Los Angeles through policy advocacy, education, and research.30,31 HAAFII plays a unique role as a broker, bringing together academic researchers and community stakeholders to jointly address health disparities using Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR), its self-developed variation on Community Based Participatory Research. CPPR structures community/academic research partnerships through power sharing, joint ownership, respectful dialogue, transparency, and equitable resource allocation in all research phases.18,32-33 HAAFII believes research done in and with community should be returned back through open community forums, joint ownership of all data and research products such as manuscripts. The agency has partnered on research beneficial to local residents through ongoing collaborations with Charles Drew University, UCLA, and RAND.

In HAAFII’s projects around maternal-child health, diabetes, and depression, agency staff realized African-American men had received little attention in research and program development and that few African-American men from South LA attended the community conferences where HAAFII presented its research. To address this gap, the agency developed an initiative to engage African-American men from the local community to enhance research capacity and program/intervention development. An initial Men’s Workgroup of 15 volunteer participants from South LA met monthly in 2005 to share their perspectives on health, mental health and healthcare and to develop this study.19

Through the Men’s Workgroup, HAAFII devised its own community-sensitive methods and language, rather than relying on those employed by academic partners. First, the agency realized that commonly used research language reinforced African-American men’s distrust of researchers and healthcare.20-22 Second, the biomedical models researchers employed did not best reflect, in the agency’s view, local conceptions of the link between perceived community stressors (e.g., poverty, unemployment, persistent racism) and the health and mental well-being of African-American men. HAAFII believed a community-led investigation would increase participation of African-American men in a research study by addressing these concerns. Finally, the agency envisioned a study to document strategies utilized by African-American men to cope with perceived stressors and to enhance resiliency in the face of racism and stress.

HAAFII and the Men’s Workgroup developed a set of open-ended questions designed to maximize limited resources, to promote broad participation from the local South Los Angeles community, and to elicit the best possible data on African-American men’s perspectives, in their own words, about sources of stress and sources of strength that aided coping and survival.

METHODS

HAAFII used a CPPR structure, discussed above and in prior publications, in all research phases, especially during data analysis and manuscript preparation where academic partnership was greatest. Pilot funds to HAAFII from the National Institute for Child and Human Development supported data collection, while funding to both HAAFII and UCLA from the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the California Community Foundation supported academic staff time for data analysis and manuscript development.

In order to capture a sample of African-American men, the researchers chose the Los Angeles African Marketplace and Cultural Faire in 2007 as the survey site. Many African-American men from the community attend this event, a city-sponsored food, arts and music festival celebrating the Pan-African Diaspora. The interview station offered educational materials from NIMH, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and Community Partners in Care, an NIMH-funded, depression care research project.34,35 Of 1275 adult males approached, 350 (27.5%) participated in the survey.

Trained HAAFII staff (African American men living in South Los Angeles 18-70 years of age) read the surveys to participants and recorded responses verbatim by hand. This approach decreased the likelihood that literacy and apprehensions about having comments audiotaped would be participation barriers. Each interview took 10-15 minutes and participants received $20 for participation. We collected no identifiers and assigned only a numerical code to each survey. The UCLA, Charles Drew University, and RAND Institutional Review Boards determined the study to be exempt.

The interviewers first requested basic demographic information. (See Table 1) Each participant then responded to eight open-ended questions, introduced as “conversation topics” (CT): CT1) “Most people have some sort of stress or drama or depression in their lives. What about you and the guys you know?;” CT2) “What are three issues that are bothering you right now?;” CT3) “Is there anything that is always bothering you or in the back of your mind?;” CT4) “Is there any help out there for you or other men to deal with stress and drama?;” CT5) “If not, why do you think that is?;” CT6) “What are some of the things that make you and guys you know feel strong and able to deal with stress or drama?;” CT7) “What are some things that make it harder to feel strong and able to deal with stress or drama?;” CT8) “Would you be interested in coming together with other men to problem-solve men’s concerns, the ones we have talked about?”

Table 1.

Demographics of 295 African-American male study participants

| Characteristics (n=295) | |

| Age (mean) | 36.2 years |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |

| Single, never married | 147 (49.8%) |

| Married/ living with partner as though married | 114 (38.6%) |

| Divorced, Separated, Widowed | 34 (11.5%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Full-Time | 139 (47.1%) |

| Part-Time | 59 (20.0%) |

| Unemployed, self-employed, casually employed | 57 (19.3%) |

| Not working due to school | 10 (10.5%) |

| Retired or disabled | 10 (10.5%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Middle School | 14 (4.7%) |

| High School | 116 (39.3%) |

| 4 year college, some college, or AA degree | 146 (49.5%) |

| Master’s Degree | 15 (5.1%) |

| MD, Ph.D., or J.D. | 4 (1.4%) |

| Resident, County of Los Angeles, n (%) | 292 (99%) |

In developing the questions, HAAFII staff paid particular attention to survey language to enhance participation by African American men. To encapsulate the idea of negative factors impacting health and well-being, they chose to use the phrase “stress or drama.” In earlier studies, we identified this language as culturally acceptable, incorporating feelings of low self-worth, inadequacy to deal with problems, and disinterest in normal activity. Many respondents, in our experience, viewed a clinical term like “depression” as stigmatizing.10,25 The surveys also utilized broad phrases such as “you and the guys you know,” because the Men’s Workgroup advised that many men would feel more comfortable answering these broad questions than directly revealing personal information.

DATA ANALYSIS

HAAFII staff (LJ, AB) analyzed the interview data in collaboration with a psychiatrist (BC) and qualitative analyst (MM). For the data analysis reported here, we focused on the 295 respondents who self-identified as Black or African-American. All data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation were conducted using CPPR methods and principles.1,18,30,32-33 The analysis team read and discussed the interviews, separated out text segments relating to particular topics and divided them into piles, suggested codes, applied these to the text and then repeated the process. After several rounds of analysis, the themes of financial stability, family concerns, and racism emerged as major sources of stress. The team developed a codebook for standard procedures and used Microsoft Excel to capture data coding. All responses were coded by respondent and by question. For CTs 1, 3-5, and 7-8, the coders chose one thematic code for each response. For CTs 2 and 6, where responses often included multiple themes, the coders applied as many codes as indicated by the content. Once all coding was completed, we retrieved all excerpts for each theme and sub-theme and wrote a descriptive summary. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Frequency of themes related to ‘stress and drama,’ resiliency, and sources of supporta

| Participants (n=295) | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Endorsed “stress or drama” | 275 (93.2) |

| ≥ 1 specific issues causing ‘stress or drama’ | 278 (95.2) |

| Of those (n=278) with specific issue causing ‘stress or drama’ (n=278)b | |

| money and finances | 169 (60.8) |

| racism | 120 (43.2) |

| finding, keeping, or succeeding at a job | 79 (28.4) |

| children and family | 76 (27.3) |

| relationships with wife or girlfriend | 61 (21.9) |

| health and illness | 42 (15.1) |

| Of those (n=120) endorsing racism as a source of stress b | |

| institutionalized | 82 (68.3) |

| personally mediated | 38 (31.7) |

| internalized | 16 (13.3) |

| “Is there help for dealing with ‘stress and drama’” (n=295) | 187 (63.4) |

| Yes | 187 (63.4) |

| Of ‘yes’ (n=187), ‘cost’ and ‘distance’ are barriers | 11 (5.9) |

| No | 69 (23.4) |

| Of ‘no’ (n=69), men should handle ‘stress and drama’ alone or didn’t care enough to seek help. |

29 (42.2) |

| no response | 39 (13.2) |

| Endorsed a strong interest in talking to other men about issues related to ‘stress and drama’ (n=295) |

191 (64.7) |

| Participants endorsing a specific source of help for ‘stress and drama’ (n=295) 76 |

(25.8) |

| Of those endorsing a specific source of help (n=76) b | |

| faith (God or church) | 32 (42.1) |

| family and friends | 21 (27.6) |

| hobbies | 64 (21.7) |

| therapy or mental health services | 5 (6.6) |

| Of those mentioning a specific sources of resiliency (n=272) b | |

| external sources of resiliency | |

| religion (“relationship with God”, Allah, prayer, or church attendance) | 67 (24.6) |

| hobbies (e.g. sports, music) | 60 (89.6) |

| family or significant other | 51 (18.8) |

| support from or activities with friends | 48 (17.6) |

| internal sources of resiliency | 39 (14.3) |

| personal self-confidence, self-esteem, and own abilities | 52 (19.1) |

| staying positive, meditation, “knowing a stressful situation will pass” | 39 (14.3) |

| Factors identified as barriers to managing stress (n=275)b | |

| lack of support or negative action of others | 68 (24.7) |

| lack of support from friends | 35 (12.7) |

| “weight of multiple problems” | 45 (16.4) |

| “no control” over their lives | 24 (8.7) |

| lack of funds or money | 32 (11.6) |

| lack of self-confidence | 20 (7.3) |

| specific references to racism | 27 (11.6) |

No statistically significant differences found between categories by age, income, or education.

Participants often gave two or more responses, so total frequencies of factors are > n.

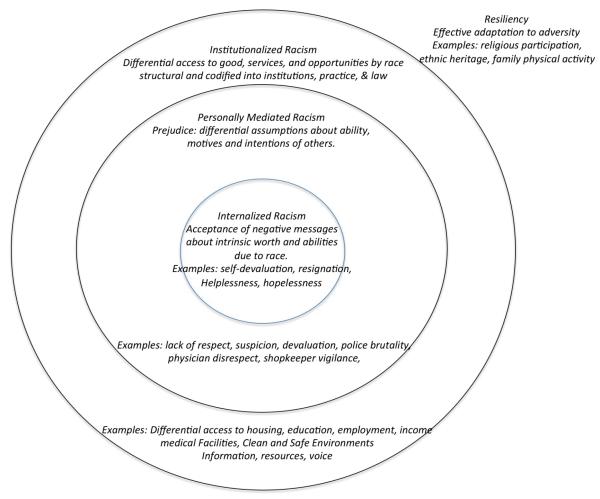

The team conducted a further analysis to clarify the significant theme of racism directed toward African-American men HAAFII staff identified as emerging from the data. The analysis group employed the Levels of Racism framework,36 which describes three levels of racism and how they affect health outcomes, as a coding strategy to find meaning in the data. Institutionalized racism, defined as differential access to goods, services and social opportunities due to race, is a structural phenomenon, generally codified in customs, practices and laws. Personally mediated racism refers to prejudice or differential assumptions about the abilities, motives and intentions of others based on race, and personal discrimination. Internalized racism describes acceptance by members of the stigmatized race of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

All 295 respondents in this sample were African-American males. Their mean age was 36.2 years. Only 3 lived outside Los Angeles County. About half (49.8%) were single and 38.6% were married or living with a partner. Nearly all (95.3%) had at least a high school education; more than half (55.9%) had at least some college education or an Associate degree (compared to 42% for South LA as a whole), while 27.1% had a baccalaureate or higher. Despite their educational level, less than half of the men (47.1%) reported being employed full-time at one or more jobs; 20% were employed part-time, while 19.3% were self-employed or unemployed (compared to an estimated 15% unemployment rate for the community). (Table 1)

Sources of Stress

Nearly all participants (93.2%) reported some level of “stress or drama” in their lives and (95.2%) identified one or more specific issues currently bothering them. (Table 2) Altogether participants identified 40 different sources of stress in their responses to CT1, CT2 and CT3. Of the sources of stress identified, money and finances was the most common (60.8%). Much less common, but still major, areas of stress were finding, keeping, or succeeding at a job (28.4%); relationships with a wife or girlfriend (21.9%); concerns about other family members, particularly children (27.3%); and health and illness (15.1%). Chi-square comparisons showed that these major sources of stress did not differ significantly by demographic characteristics. This pattern of sources of stress is similar to other stressors reported by low-income men, regardless of racial identity.37

Racism emerged as the second most significant theme. Two-fifths (43.2%) of respondents identified sources of stress that were racially-linked or mediated, including specifically identified experiences of racism directed against them as African-Americans; denials of rights; disrespect shown by the police or local government; lack of unity or strength in the black community; prevalence of violence and criminality in the black community. These responses were often linked to personal concerns about finances, work, and family relationships. Of those who endorsed racism (n=120) as a source of stress, nearly 70% (68.3%) endorsed responses identified as institutionalized racism, about one-third (31.7%) as personally mediated racism, and only 13.3% as internalized racism.

Sources of Help and Resiliency

In response to the question, “Is there help out there for men dealing with ‘stress and drama?’”, most participants (63.4%) believed there was help available, with about one-quarter (25.8%) identifying one or more specific sources of help. (Table 2) The most commonly cited were God or the church (42.1%) and family and friends (27.6%). About 6% (5.9%) believed that cost and distance are barriers to receiving help. Only one-fifth of the group (23.4%) thought there was no help. The most common explanations given by those who stated that no help was available were that men were expected to handle the issue themselves, or didn’t care enough to seek help (42.2%).

The analysis also focused on sources of resiliency, defined as a pattern of effective or positive adaptation to significant challenges, risks or adversity.38 Men described 21 different resources that helped them to work through stress and experiences of racism and to maintain physical and emotional health. Only 6.6% made any reference to the use of professional therapy or mental health services. The most frequent source of help for stress identified (42.1%) was again “a relationship with God” or Allah, faith, prayer, and church participation. Almost all (89.6%) men described relying on sports, music or a hobby for relief; 18.8% drew comfort from family members or a significant other; and another 17.6% of men stated that they talked issues through with friends, “just getting together and brainstorming, chopping it up.”

More than half (52%) of men relied on their own abilities, personal self-confidence, or self-esteem, which some attributed to “Being African…We are strong people and all we know is to survive.” A second group of were less self-confident, but stated that they dealt with stress by staying positive, sometimes meditating, and “knowing that the stressful situation will pass.” These statements appeared to mirror the ideas expressed above that men were expected to cope with stress issues on their own and had developed personal tools to do so. For some, black identity, “just being a strong black man,” was a source of strength; as one noted, “The Internet and library are fully stocked with encouraging examples of black men who have overcome similar stresses.”

When asked what made it difficult to deal with stress, there were again multiple responses. Nearly one-quarter (24.7%) men of citing barriers to managing stress mentioned lack of support or negative actions of others – including media, police, prospective employers, or “haters” and general “negativity,” or “when everybody turns their back on you.” Over 12% (12.7%) of men talked about lack of support from family or friends, 16.4% of men cited the sheer weight of multiple problems and 8.7% said they simply had “no control” over their lives. Nearly 12% (11.6%) of men noted “lack of funds” was a barrier and 7.3% noted lack of self-confidence. Over 10% made specific reference to racism: “knowing that I am a part of group of human beings that have been constantly oppressed, repressed, suppressed and depressed,” with some adding that there is disunity within the African-American community, “racism is still an issue and is very strong amongst ourselves.”

Levels of Racism

Institutionalized racism

Many respondents who were stressed by low income, unemployment or less than full employment, or inability to make ends meet perceived these problems as resulting from lack of economic, educational, and employment opportunities. Representative statements included: “the lack of opportunity, especially for black men, [in] employment, education, etc.;“ “the lack of economic development” and “no manufacturing” in the local African-American community; “lack of education for the community;” failures of “Medicaid affecting the black community;” “the condition of black Americans and the lack of economic empowerment”; “the corrupt system in America;” lack of “black economic progress;” “The system sets up black men to fail,” by not instituting “formidable policies that deal with black men’s issues.”

Concerns about community violence and “gang violence,” especially in regards to children, were also repeatedly cited as sources of stress: for example, “remaining safe at work” and “the safety of my son growing up in LA,” with the constant risk of “drive-by shootings.” One respondent said, “My friends keep getting murdered;” another feared “gangs hitting me up when I’m not involved.” The violence was seen by many as attributable to the apathy or active aggression of the “gang called police:” “young blacks are killing each other,” while “the police are killing us (blacks).”

A final theme in this category was perpetuation of racism through “media portrayal of the African-American male” and society’s “lack of understanding of us black people.”

Personally-mediated racism

Multiple participants cited racially-based discourteous treatment as a frequent stressful event. For example, one man stated, “most black men encounter racism on a frequent daily basis. It’s a way of life that’s expected.” Another described himself as having “post-traumatic stress just from being here, male, and black.” Again, “the disrespectful, racist police” were prominent examples: “In my neighborhood, the police just harass you for no reason;” and black men suffer “abuse by the LAPD.” “When,” asked one participant, “will my people truly be at liberty?”

A major secondary construct in this category was African-American men’s relationships with women. Multiple respondents referred to “baby mama drama” or to “women – the most thing that creates stress;” while interpersonal problems are common to all ethnicities, many responses reflected internalized perceptions of racial stereotyping within close relationships. As one man explained, “blacks are disrespected and demonized in mainstream society, and…are openly/acceptably devalued by black women.” Another cited as his one consistent stressor, “how to get black women to stop trying to be black men.”

Internalized racism

Many respondents described not being able to live up to their perceived potential because they had internalized negative messages about their self-worth as African-American males. One noted his “fear of not being able to show my talents;” another worried about his “lack of knowledge of self.” A third stated emphatically, “We black men don’t like to get help…Black men just keep it bottled in” because “men are supposed to be strong and can bear everything.” However, this participant felt, “men do need help.”

Respondents saw these negative messages as also affecting their whole community, producing “self-hatred among black folk,” with the results that “black people [are] not doing the things they should be,” “not unifying to save ourselves;” black children have “low school performance;” and there is “a lack of positive black male role models within the community.”

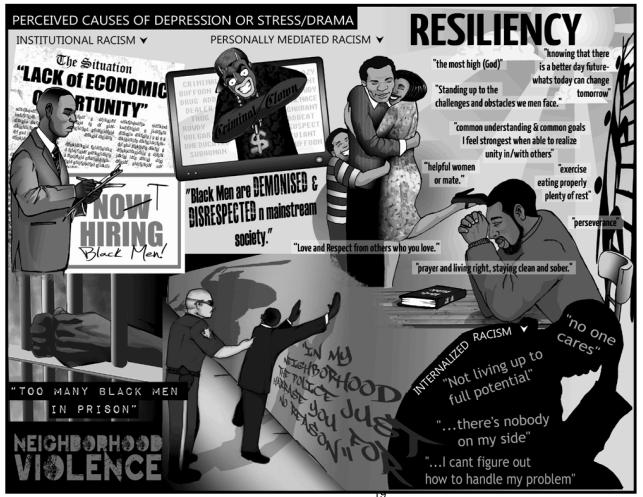

HAAFII staff decided a summary of the analysis using the Levels of Racism framework combining drawings as well as quotations from the data would be the most relevant way to engage the local community around study findings. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

The community partners developed this drawing, incorporating participant quotations, as a device for engaging local African-American men around the study findings.

DISCUSSION

The grassroots health advocacy agency, HAAFII, conceived and implemented this study with limited resources and academic consultation. The agency capitalized on its research strengths, community knowledge and community participation in study design and data collection, while partnering with academic researchers on data analysis and manuscript development. This experience contributed to HAAFII’s success in building significant research capacity and in contributing its community expertise and engagement approaches to large, collaborative studies with its academic partners, UCLA, Charles Drew University and RAND Health.12,18-19,29-35

The data analyzed documents the perceived sources of “stress and drama” in the lives of African-American men in a major urban community. Although many of the responses cited economic and family problems common among low-income men, racism and discrimination pervaded the data, both as specific causes of stress and as mediators of stress associated with financial, employment, community, relationship, and family issues. The declining U.S. economy in 2007 may be one reason that over 60% men cited money and finances as significant stressors.39 Our findings were consistent with other qualitative studies that have examined the perspectives of this race/gender group.40-43 The elicited themes and specific quotations from participants reflect the broader literature on the social determinants of health, which documents low socioeconomic status, lack of work, relationships, environmental stressors, racism, discrimination, and marginalization, as significant contributors to poor mental health.44-50 In our analysis, there were no statistically significant associations between demographic characteristics and endorsement of “stress and drama” or types of stress. The findings indicate that racist attitudes and structures continue to be perceived as deleterious to African-Americans’ quality of life.

Also significant in our data was the recurrent reliance on personal resources, being “a strong black man,” and family, friends, and faith. These findings reflect literature documenting African-American culture, family and religion as crucial resources to alleviate distress and assist coping.41-43,51 Our work resonates with Becker and Newsom’s identification of resiliency as a key value in African-Americans’ struggle for social justice and freedom:

“African heritage, cataclysmic disruptions caused by slavery, ensuing historical eras such as Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and continuing racial oppression have all reinforced an emphasis on overcoming obstacles against all odds. The resulting values have been characterized as a ‘survival arsenal.”52

Our emphasis on participants’ perceived strengths contrasts with a deficit model of health. Although data collection for this study took place at a station offering depression education materials, few respondents alluded to professional treatment or care as a source of help. Instead, respondents emphasized their use of positive relationships and activities to maintain quality of life despite ongoing stress.

Future work may be to utilize study findings to adapt existing evidence-based interventions to improve health outcomes for African American men. One intervention our group would like to adapt is the depression care toolkit utilized in a recently published manuscript from Community Partners in Care (CPIC). In CPIC, our group found in a randomized trial that a community planning and network building approach relative to technical assistance for implementing evidence-based, collaborative care for depression in Los Angeles over 6 months led to greater improvement in mental health-related quality of life, physical activity, reduced indicators of homelessness or having multiple risk factors for future homelessness, and reduced behavioral health hospitalizations, while shifting the mix of outpatient services somewhat away from mental health specialty medication visits and toward primary care and alternative sectors such as faith-based and park and recreation centers.35 Our group would like to adapt the CPIC depression care interventions to address perceived sources of distress such as financial insecurity, employment, or racism, as well as to enhance resiliency by building on existing coping tools such as family, friends, religion, and cultural values. Analogous examples from the literature include an evidence-based HIV-prevention intervention for African-American adolescent girls that celebrated African-American women’s contributions to history and art in the first several sessions;53,54 a participatory approach with low-income pregnant East Indian women that incorporated community planning, leading to improvements in both birth outcomes and post-partum depression symptoms;55 and multiple initiatives that have addressed housing as a social determinant within health programs for homeless, mentally ill, and HIV-positive individuals.56-59

This study had several limitations. First, because we utilized a convenience sample, our results reflect only the perspectives of those men who had the time and interest to spend part of a weekend at the African Marketplace and agreed to participate. Our results may not be generalizable to areas outside Los Angeles or to men who did not participate. Because HAAFII staff prioritized face and perceived community validity to maximize participation, the psychometric validity and reliability of survey items has not been established. For example, we chose not to ask about income levels, as the agency felt this would discourage participation. Similarly, the survey asked participants to answer about themselves and “other men,” instead of directly asking the men how they would feel because HAAFII felt being too direct would decrease participation.

This study has significant strengths. First, the health advocacy organization, HAAFII, designed and implemented the study with limited academic consultation. Academic partners were utilized for qualitative analysis and manuscript preparation. This project demonstrates the transformative opportunity participatory research offers communities to add their voices to research.60 By partnering with academic researchers, HAAFII was able to develop the study, analyze the data, and write a manuscript to provide important data and community perspectives on African American men, a group with generally low rates of participation in research studies.3,61 Second, our qualitative sample of 295 African-American men is the largest to date to explore the perspectives of this particular group on perceived sources of stress. Despite its methodological limits, this project both presents a workable model for community-based agencies to begin engagement in health research and highlights the significance of racism as an important source of “stress” and reduced health quality among African-American men from South Los Angeles.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE STUDY?

To understand perceived causes of stress and tools used to promote resiliency in African American men in South Los Angeles.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

African American men are at higher risk for a number of adverse health outcomes including more morbidity from health and mental disorders and more than 5 years lower life expectancy than men from other racial groups

Limited research exists on understanding what are the perceived stressors and factors that promote resiliency that may be important factors to address to improve the health outcomes of African American men.

WHAT ARE THE FINDINGS?

Almost all (93.2%) men reported stress.

Of those reporting stress, about 60% reported that finances / money and about 40% reported were specific causes of stress.

Two-fifths (43.2%) of men reported sources of stress that were racially linked including experiences of racism such as denials of rights, disrespect shown by police or local government.

Over 60% of study participants reported they perceived that help was available to deal with stress.

Almost all the participants reported specific sources of resiliency such as religion and family helped alleviate the burden of perceived stressors.

WHO SHOULD CARE THE MOST?

Community organizations and service providers supporting African-American men such as healthcare, mental health, substance abuse, churches, and social services agencies.

Researchers and policy makers interested in improving health outcomes for and with African American men.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION

Future research and program development to engage African-American men should account for both the perceived causes of stress such as finances and racism, as well as incorporate culturally appropriate sources of support for resiliency such as religion and family.

Figure 1.

Adaptation of the Levels of Racism Model29 as described by C.P. Jones, MD, PhD.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute, NCATS #UL1TR000124; NIMH grant # MH078853, MH082760; NLM grant # G08LM011058

REFERENCES

- 1.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P. Mental health in the context of health disparities. The American Journal of Psychiatry. Sep. 2008;165(9):1102–1108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias E, Curtin LR, Wei R, Anderson RN. U.S. decennial life tables for 1999-2001, United States life tables. National Vital Statistics Reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2008 Aug 5;57(1):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satcher D. Overlooked and underserved: improving the health of men of color. American Journal of Public Health. May. 2003;93(5):707–709. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the national survey of american life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007 Mar;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Neighbors H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethnicity & disease. Fall. 2001;11(4):800–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 Sep;98(9 Suppl):S29–37. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking Wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. American Journal of Public Health. 2009 Feb;99(2):237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miranda J, Ong MK, Jones, et al. Community-Partnered Evaluation of Depression Services for Clients of Community-Based Agencies in Under-Resourced Communities in Los Angeles. May 14, 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Pascoe EA, Smart-Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009 Jul;Vol 135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Williams DR, Diez-Roux AV, Gordon-Larsen P. Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63(6):1415–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Ment Health Journal. 2006;42(6):555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanyam MA, James SA, Diez-Roux AV, Hickson DA, Sarpong D, Sims M, Taylor HA, Jr, Wyatt SB. Socioeconomic status, John Henryism and blood pressure among African-Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Social Science and Medicine. 2013 Sep;93:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.016. Epub 2013 Jun 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethnicity & disease. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu MC, Jones L, Bond MJ, et al. Where is the F in MCH? Father involvement in African American families. Ethnicity & disease. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):S2-49–61. Winter. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Diane MMSG. Distrust, Race, and Research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:2458–2246. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(11):1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Social, Science, and Medicine. Mar. 2001;52(5):797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner JA, Tennen H, Finan PH, Ghuman N, Burg MM. Self-reported Racial Discrimination and Endothelial Reactivity to Acute Stress in Women. Stress and Health : Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2012 Sep 7; doi: 10.1002/smi.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster ML, Arnold E, Rebchook G, Kegeles SM. ‘It’s my inner strength’: spirituality, religion and HIV in the lives of young African American men who have sex with men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011 Oct;13(9):1103–1117. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.600460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendrick L, Anderson NL, Moore B. Perceptions of depression among young African American men. Family & Community Health. 2007 Jan-Mar;30(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis-Coles ME, Constantine MG. Racism-related stress, Africultural coping, and religious problem-solving among African Americans. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006 Jul;12(3):433–443. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teti M, Martin AE, Ranade R, et al. “I’m a keep rising. I’m a keep going forward, regardless”: exploring Black men’s resilience amid sociostructural challenges and stressors. Qualitative Health Research. 2012 Apr;22(4):524–533. doi: 10.1177/1049732311422051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health. 2012 May;102(Suppl 2):S232–41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. Epub 2012 Mar 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferré CDJL, Norris KC, Rowley DL. The Healthy African American Families (HAAF) project: from community-based participatory research to community-partnered participatory research. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):1–8. Winter. 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones L. Preface: community-partnered participatory research: how we can work together to improve community health. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S6-1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones L, Collins BE. Participation in action: the Healthy African American Families community conference model. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):S2-15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N. Begin your partnership: the process of engagement. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19:S6–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:407. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K. Using a Community Partnered Participatory Research Approach to Implement a Randomized Controlled Trial: Planning the Design of Community Partners in Care. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(3):780. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-Partnered, Cluster-Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Community Engagement and Planning or Program Technical Assistance to Address Depression Disparities. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013 May 7; doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health. 2000 Aug;90(8):1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebbeck TR, Weber AL. What stresses men? Predictors of perceived stress in a population-based multi-ethnic cross sectional cohort. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:113–130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985 Dec;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The 2007 Economy in Review, Jim Zarroli, Morning Edition, National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17716248.

- 40.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997 Jul;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wittink MN, Joo JH, Lewis LM, Barg FK. Losing faith and using faith: older African Americans discuss spirituality, religious activities, and depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009 Mar;24(3):402–407. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0897-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant-Bedell K, Waite R. Understanding major depressive disorder among middle-aged African American men. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010 Sep;66(9):2050–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egede LE. Beliefs and attitudes of African Americans with type 2 diabetes toward depression. The Diabetes Educator. 2002 Mar-Apr;28(2):258–268. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 Sep;98(9 Suppl):S150–157. doi: 10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, Holt J. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: the added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health. 2006 Oct;96(10):1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broman CL, Mavaddat R, Hsu SYTeacoprdAsoA-AJBP- The experience and consequences of perceived racial discrimination: A study of African-Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 26(2):165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;60(8):789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010 Mar;100(3):452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2010 Aug;100(8):1477–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born Black Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2011 Sep;101(9):1704–1713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Utsey S, Giesbracht N, Hook J, Stanard P. Cutlural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distressin African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race related stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becker G, Newsom E. Resilience in the face of serious illness among chronically ill African Americans in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005 Jul;60(4):S214–223. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. A randomized controlled trial of an HIV sexual risk-reduction intervention for young African-American women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995 Oct 25;274(16):1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004 Jul 14;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women’s groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Browne G, Courtney M. Measuring the impact of housing on people with schizophrenia. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2004 Mar;6(1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2003.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwarcz SK, Hsu LC, Vittinghoff E, Vu A, Bamberger JD, Katz MH. Impact of housing on the survival of persons with AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchanan D, Kee R, Sadowski LS, Garcia D. The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patients: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2009 Nov;99(Suppl 3):S675–680. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Campo P, Kirst M, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Firestone M, Scott A, McShane K. Community-based services for homeless adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders: a realist approach to synthesizing evidence. Journal of Urban Health. 2009 Nov;86(6):965–989. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Byrd GS, Edwards CL, Kelkar VA, et al. Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research studies: a major research challenge. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011 Jun;103(6):480–7. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]