Abstract

Adolescents and adults engage in anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) misuse seeking their anabolic effects, even though later on, many could develop neuropsychological dependence. Previously, we have shown that nandrolone induces conditioned place preference (CPP) in adult male mice. However, whether nandrolone induces CPP during adolescence remains unknown. In this study, the CPP test was used to determine the rewarding properties of nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg) in adolescent mice. In addition, since D1 dopamine receptors (D1DR) are critical for reward-related processes, the effect of nandrolone on the expression of D1DR in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) was investigated by Western blot analysis. Similar to our previous results, nandrolone induced CPP in adults. However, in adolescents, nandrolone failed to produce place preference. At the molecular level, nandrolone decreased D1DR expression in the NAc only in adult mice. Our data suggest that nandrolone may not be rewarding in adolescents at least during short-term use. The lack of nandrolone rewarding effects in adolescents may be due, in part to differences in D1DR expression during development.

Keywords: Anabolic-androgenic steroids, reward, adolescents, D1 dopamine receptors, nucleus accumbens

1. Introduction

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are considered drugs of abuse, being misused at supraphysiological doses by an increasing number of athletes and adolescents (Bahrke et al., 1998). The use of AAS by teenagers has been a primary public health concern because of their potential side effects during a period where remodeling of the brain and behavioral maturation occurs. The lifetime prevalence of AAS misuse for adolescents has been estimated to be 4–6% in males and 1.5–3% in females (Harmer, 2010). This and other epidemiological reports support studies that link early initiation of AAS misuse with increased risk for psychiatric dysfunction, steroid dependence, as well as a higher risk to engage in the use of other illicit drugs (Kanayama et al., 2009). However, during the last decade, studies that assessed rewarding properties of AAS have been mainly done in adult animal models. In fact, a growing body of work in adult rodents shows that androgen compounds have hedonic and reinforcing effects (Clark and Henderson, 2003; Wood, 2004). These effects have been observed using different behavioral paradigms such as conditioned place preference (CPP) or self-administration (Clark and Henderson, 2003; Wood, 2004). Recently, we have demonstrated, in adult mice, that pharmacological doses of the anabolic steroids, testosterone (T) propionate (0.075, 0.75 and 7.5 mg/kg) or nandrolone (0.75 and 7.5 mg/kg but not 0.075 mg/kg), shifted place preference during the CPP (Parrilla-Carrero et al., 2009). Still, the rewarding properties of AAS during adolescence have remained undetermined.

The AAS-induced rewarding effects seem to be mediated directly or indirectly by the corticomesolimbic dopamine reward system (Triemstra et al., 2008). This circuit, which is critical for regulating reward-related associative learning (Kindlundh et al., 2004), is mainly composed of the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc) and prefrontal cortex (PFC; Koob and Volkow, 2010). In this context, rewarding stimuli lead to increments of dopamine release to the NAc from the VTA. Although D1 and D2 dopamine receptors (D1DR and D2DR) are key players for the signaling process of reward, the D1DR are the most critical in reward-related learning (Beninger and Miller, 1998). In this line of evidence, Kindlundh and colleagues (2001, 2003) have shown that nandrolone altered proteins and transcripts of the dopamine receptors within the striatum and NAc. Moreover, accumbal administration of flupentixol, a D1/D2 dopamine receptor antagonist, blocked the expression of androgen-induced CPP (Packard et al., 1998).

In the present study, the rewarding properties of nandrolone, one of the most abused AAS (Lood et al., 2012), were assessed using an adolescent animal model. Furthermore, we addressed the molecular modulation of nandrolone in the NAc through the expression of D1DR. Knowing that adolescents engage in high reward motivated behaviors (Wahlstrom et al., 2010) due to developmental changes in the striatum that confer reward hypersensitivity (Galvan, 2010), we hypothesized that exposure to nandrolone during this developmental stage will induce: i) an increase in place preference, and ii) an increase in the levels of accumbal D1DR protein expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

C57Bl/6 male mice were purchased from Charles River and housed individually in the Animal Resources Center with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were kept on a reverse 12:12 hour light/dark cycle. The behavioral experiments were performed during the dark phase of the cycle, in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus.

2.2. Androgen administration

Similar to previous experiments, adolescent and adult experimental groups received intraperitoneal (IP; Hoseini et al., 2009; Witzmann, 1988) injections of nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg; 19-nortestosterone; Sigma Chemical Co. St. Louis, MO), whereas control groups received IP injections of vehicle, which consisted of sesame oil (0.02 cc/10g of body weight. As 1 mg/kg of AAS is sufficient to restore endocrine function and reproductive behaviors in rodents (Clark and Barber, 1994), the dosage used in this experiment reflects a high dose. Since periadolescence in rodents extends from postnatal (PN) day 28 to PN-60, (Spear, 2000), nandrolone injections alternated with vehicle injections, were started at PN-33 until PN-42 (Fig. 1). Furthermore, to confirm our previous experiment in adults (Parrilla-Carrero et al., 2009), adult male mice (PN 88-97) were also tested following the same CPP injection protocol as in adolescents.

Figure 1. Experimental design and injection protocol for the CPP in nandrolone-treated animals.

The CPP was performed for 14 days. On days 1–2, animals were habituated to the CPP chambers for 15 min. On day 3 (baseline), animals were allowed to move freely between the compartments for 15 min. The time spent in each compartment was immediately calculated. During days 4–13 (conditioning), nandrolone-treated animals received alternate injections of drug (days 4, 6, 8, 10, 12) or vehicle (days 5, 7, 9, 11,13) while placed for 30 min in the non-preferred (NP) or preferred (P) side, respectively. Control animals received daily injections of vehicle, whether they were restricted to the NP or P side of the chamber. On day 14 (test day), injection-free animals were allowed to move freely between the compartments, and the time spent in the NP side was recorded for 15 min.

2.3. Conditioned place preference (CPP)

This behavioral paradigm was performed as previously described (Parrilla-Carrero et al., 2009) with some modifications. In brief, the apparatus consisted of an acrylic cage separated in two compartments by an opening that can be closed by a removable guillotine door. The chambers comprised of two sides. One side of the chamber has smooth flooring, lateral walls with black and white lines, and anterior/posterior white walls. The other side has grated-texture flooring, lateral walls with black and white checkers, and anterior/posterior black walls.

The CPP was performed using a biased design and under semi dark conditions. Briefly, the CPP protocol lasted 14 days and consisted of four phases (Fig. 1): habituation (days 1–2), baseline (day 3), conditioning (days 4–13) and test day (day 14). During the baseline (15 min), animals were recorded for the time spent in each side of the chamber to determine the non-preferred (NP) side (where the drug will be injected during conditioning). Thereafter, animals were randomly assigned to control or experimental groups. The conditioning phase consisted of a 30 min session per day. The experimental group received nandrolone injections (days 4, 6, 8, 10, 12) while they were restricted to the NP side, or vehicle injections while restricted to the preferred (P) side (days 5, 7, 9, 11, 13). The control group received daily vehicle injections whether they were restricted to the NP or P side of the chamber. Overall, both groups received a total of 10 injections. On the test-day, all animals were tested for the time spent in the NP-side in the absence of further vehicle or nandrolone injections. The time in the CPP compartments was gathered using the Any-Maze tracking system (Stoelting Co, IL). Data were obtained as the time (sec) the animals spent in the P and NP sides during the test-day. The time spent in the NP side between control and experimental animals was reported and statistically compared.

2.4. Western blot analysis

2.4.1. Sample preparation

Nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg) and vehicle treated adolescent and adult mice were sacrificed by rapid decapitation, and the NAc rapidly dissected as previously described (Sharma and Fulton, 2012). Tissue was homogenized and lysed using CelLytic MT with SIGMAFAST™ Protease Inhibitor Tablets (Sigma–Aldrich, MO). Supernatants were collected to determine total protein concentration using Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, CA).

2.4.2. Western blotting

Western blots were performed as previously described (Silva, et al., 1999) with some modifications. Immunodetection of D1 dopamine receptor (D1DR) and β-actin on nitrocellulose membranes was performed using a 1:1000 dilution of a primary goat anti D1DR polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) and 1:5000 dilution of a primary rabbit anti β-actin polyclonal antibody (Abcam, MA). Secondary antibodies, anti-goat polyclonal (1:10,000) or anti-rabbit polyclonal (1:15,000; Sigma-Aldrich, MO) were used. Blots were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (SuperSignal Femto, Pierce, IL) and images were obtained using a VersaDoc 1000 system (Bio-Rad, CA). Western blots were performed in triplicate from three independent experiments, and densitometric analysis performed using NIH ImageJ (v1.47d).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The number of animals per experiment is as follows: CPP for adults (vehicle n=5; nandrolone 7.5 mg/kg n=6); CPP for adolescents (vehicle n=15; nandrolone 7.5 mg/kg n=11); Western blot experiments, n=three (3) technical replicates of four (4) independent experiments (n=4 animals) for each group. Student’s t-test analyses were employed for both the CPP and Western blots. Statistical significance was established as *P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Conditioned place preference (CPP)

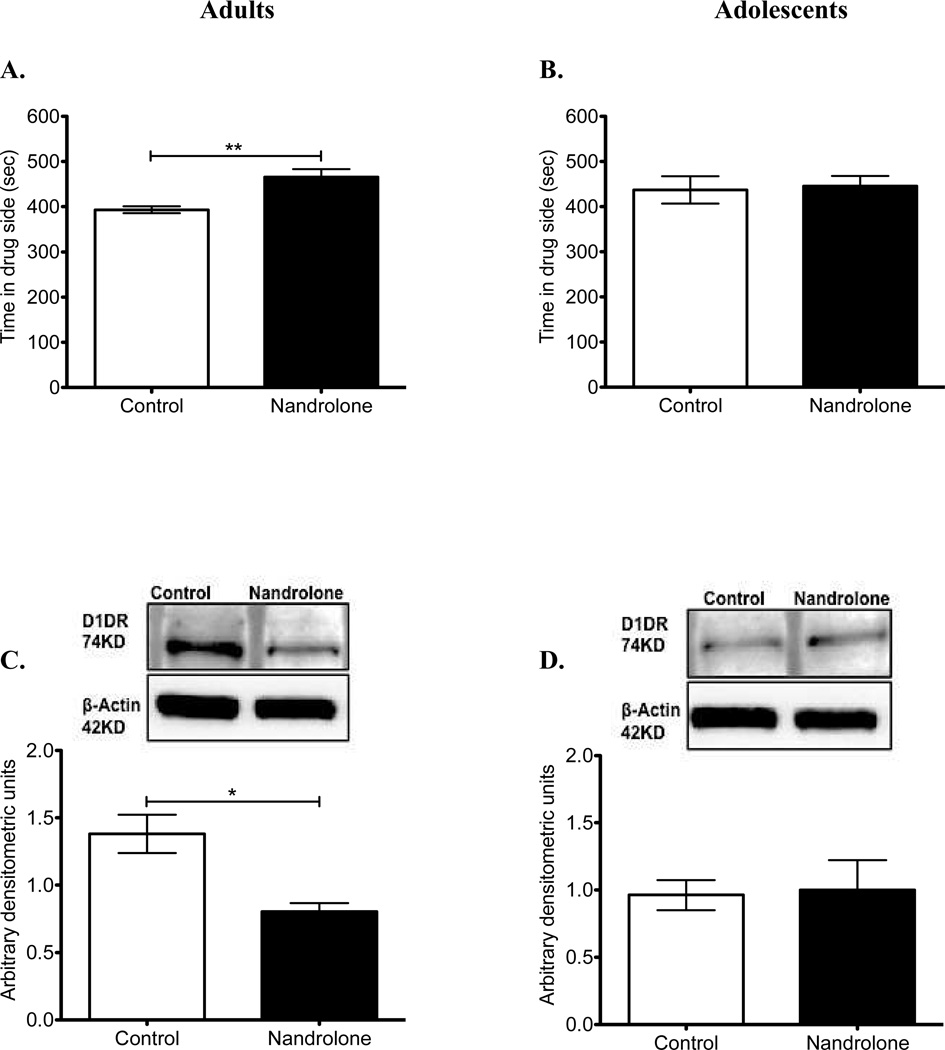

We tested the effect of nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg) in adolescent and adult mice in the CPP task. Similar to our previous findings (Parrilla-Carrero et al., 2009), in the present study we confirmed the rewarding properties of nandrolone in adult mice (Fig. 2A). Specifically, control animals spent 393.54 ± 7.84 sec in the drug-paired side, whereas the nandrolone-treated animals spent 465.63 ± 17.64 sec (t9=3.47; P=0.007). On the other hand, nandrolone failed to reveal place preference in adolescent mice (Fig. 2B). Specifically, control animals spent 437.27 ± 30.10 sec in the drug-paired side, whereas nandrolone-treated animals spent 445.77 ± 22.08 sec (t24=0.21; P=0.830). In order to conclusively state that there are no effects in the adolescent brain we also tested two lower doses of nandrolone. Similar to the higher dose, no significant effects (F(3, 43) = 0.079; P=0.971) were observed at 0.75 mg/kg (447.24 ± 44.46) and 0.075 mg/kg (424.97 ± 41.60).

Figure 2. Effect of nandrolone on CPP and accumbal dopamine receptor-1 (D1DR).

During the CPP test day, the time in the drug-paired side was recorded in adults (A) and adolescent (B) mice after exposure to alternate injections of nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg). (C–D) Representative western blot of protein extracts from control and nandrolone-treated adult and adolescent mice. Densitometric analysis of D1DR levels normalized to β-actin showed a significant decrease in D1DR expression levels in nandrolone-treated adult mice when compared to control mice (C), while no changes were observed among adolescents (D). For CPP, Adults: vehicle-n=5; 7.5 mg/kg-n=6. Adolescents: vehicle-n=15; 7.5 mg/kg-n=11. **P<0.01, unpaired t-test. For D1DR expression, *P<0.05, unpaired t-test. N=three replicates of four independent experiments for each group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

3.2. Western blot analysis

3.2.1. Accumbal D1DR expression

To begin to explore the molecular basis possibly contributing to the differential sensitivity in reward between adults and adolescents after nandrolone exposure (7.5 mg/kg), we performed a Western blot analysis for the expression of D1DR. In adult mice, densitometric quantification of D1DR (74-KD band) after normalization to β-actin showed that nandrolone decreased D1DR protein expression levels within the NAc (t4=3.695; P=0.0209; Fig. 2C). On the contrary, nandrolone treatment (7.5 mg/kg) did not affect D1DR in adolescent mice (Fig. 2D). In order to conclusively state that there are no effects in D1DR protein expression levels, we also tested two lower doses of nandrolone (0.75 and 0.075 mg/kg). Similar to the higher dose, no significant effects were observed at any lower dose tested (F(3, 14) = 2.46; P = 0.11). Regarding control levels of expression, D1DR showed a tendency to be higher in adults than in adolescents (t4=2.311; P=0.08).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that in adolescents, nandrolone was not rewarding, even though the contrary has been observed in adult animals. Since adolescents typically engage in high reward motivated behaviors (Ernst et al., 2009), and this age group has been shown to express hypersensitivity to some drugs of abuse (Schepis et al., 2008), we expected to find nandrolone-induced place preference at this developmental age. In general, although the literature suggests that adolescents may be more sensitive to the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse (Ernst et al., 2009; Galvan, 2010), several studies revealed that such sensitivity during adolescence is drug-dependent. For instance, Schramm-Sapyta and colleagues (2009) showed that amphetamine and methamphetamine stimulate less locomotion in early adolescents than their adult counterparts. In contrast, exposure to cocaine or opioids appears to induce greater locomotor sensitization in adolescents than in adults (Caster et al., 2005, 2007; Schramm-Sapyta et al., 2004; Spear, et al., 1982).

At the molecular level, we found that nandrolone decreased the expression of D1DR in the NAc of adult animals. Consistently, Kindlundh and colleagues (2001, 2003) showed that 2-week exposure to nandrolone (15 mg/kg) significantly decreased protein and mRNA expression of D1DR in the NAc of adult rats. Likewise, downregulation of dopamine receptors has been shown in studies of psychostimulants and opioids, suggesting a stimulation of the reward circuit through an increase in accumbal dopamine levels (Dumartin et al., 1998). This sustained stimulation produces desensitization through receptor internalization that ultimately produces a decrease in protein expression (Christie, 2008; Dumartin et al., 1998). Besides D1DR modulation, nandrolone elicited an increase in D2DR and dopamine transporter (DAT) expression in the VTA and striatum (Kindlundh et al., 2001, 2003, 2004). Indeed, we have gathered preliminary data suggesting an increase in accumbal DAT from adult mice exposed to nandrolone (7.5 mg/kg). Together, these findings and ours suggest a homeostatic regulation of dopaminergic activity in the reward circuit in androgen sensitive-afferent neurons.

Certainly, our study showed a lack of nandrolone modulation in the expression of adolescents D1DR, data that goes in accordance with the absence of CPP at this developmental stage. The fact that we observed a tendency for less expression of D1DR in adolescent control mice as compared with their adult counterparts could be interpreted as that the mesolimbic dopaminergic system in adolescents is not sensitive or fully mature to elicit reward-related behaviors in response to nandrolone. Evidence suggests that the dopaminergic system matures during adolescence (Kuhn et al., 2010). Accordingly, dopamine fiber densities in the NAc increase significantly during gerbils’ adolescence, suggesting that significant maturation of VTA dopaminergic projections to the NAc occurs at this stage of development (Lesting et al., 2005). In this respect, it seems that although the specific markers for the dopaminergic mesolimbic system, such as D1DR and D2DR increase markedly from PN-5 to PN-40 in the NAc and frontal cortex (Kuhn et al., 2010), the maturation process that occurs until PN-60 might play an important role for saliency and reward, particularly for androgens.

Finally, since the complex metabolism pathways that respond to androgens are not fully developed during puberty (Salas-Ramírez et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2008), we cannot rule out the possibility that developmental differences in metabolic regulation could be responsible for the lack of CPP in adolescents. Regarding nandrolone metabolism, it can be aromatized to 17β-estradiol by aromatase although to a lesser extent if compared to T (Clark and Henderson, 2003). In fact, although the expression of this enzyme decreases through development (Gillies and McArthur, 2010; Lauber and Lichtensteiger, 1994) it has been shown to be upregulated in adults after nandrolone exposure (Roselli, 1998; Takahashi et al., 2007). In this line of evidence, DiMeo and Wood (2006) showed estradiol self-administration in male hamsters, while the same hormone induced CPP in ovariectomized rats (Frye and Rhodes, 2006), a cellular response that could be mediated through estrogen receptors in the NAc (Walf et al., 2007).

However, the VTA and NAc have few androgen and estrogen receptors (AR and ER; Shughrue et al., 1997). Thus, it is likely that androgens interact with the mesolimbic system through androgen-sensitive afferents such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, amygdala and medial preoptic nucleus (MPN), which have abundant expression of AR and ER (for review see Sato et al 2008; Handa et al., 1996). Therefore, the fact that these brain regions are still undergoing maturation could be a plausible explanation for the lack of effect of nandrolone in adolescents. In this respect, it is noteworthy that a significant increase in the expression of AR occurs between PN-28 to PN-49 in the MPN (Meek et al., 1997), a similar time period in which our conditioning protocol for nandrolone was applied. Similarly, since the ER expression increases onward into adulthood (Gillies and McArthur, 2010; Romeo et al., 1999), a major responsiveness to the activational effects of steroid hormones could be expected in rewarding behaviors in adult mice.

Taken together, it is suggested that differences in the expression of structural components of the mesolimbic reward circuit, as well as differences in metabolic processing are key candidates to be further studied with the aim to understand androgen sensitivity throughout development.

Highlights.

The anabolic steroid nandrolone induces CPP in adult, but not adolescent mice

Nandrolone decreases accumbal D1 dopamine receptors only in adult mice

Rewarding effects of nandrolone are dependent on stages of development

Acknowledgements

Source of funding

This work was supported by NIH-NCRR (2P20RR016470) and NIH-NIGMS (8P20GM103475) to J.L. Barreto-Estrada, MBRS-RISE-MSC (R25-GM061838) to F.J. Martínez-Rivera and N.A. Martínez. Partial support was also received by the Associate Deanship of Biomedical Sciences at UPR-MSC. Research contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the funding agencies.

We thank Dr. María Sosa and Dr. Demetrio Sierra-Mercado who critically reviewed the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AAS

anabolic androgenic steroids

- AR

androgen receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- D1DR

D1 dopamine receptor

- D2DR

D2 dopamine receptor

- ER

estrogen receptor

- IP

intraperitoneal

- MPN

medial preoptic nucleus

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- T

testosterone

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PN

postnatal

- NP

non-preferred

- P

preferred

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bahrke MS, Yesalis CE, Brower KJ. Anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse and performance-enhancing drugs among adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7:821–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beninger RJ, Miller R. Dopamine D1-like receptors and reward-related incentive learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caster JM, Walker QD, Kuhn CM. A single high dose of cocaine induces differential sensitization to specific behaviors across adolescence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:247–260. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caster JM, Walker QD, Kuhn CM. Enhanced behavioral response to repeated-dose cocaine in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:384–396. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark AS, Barber DM. Anabolic-androgenic steroids and aggression in castrated male rats. Physiol. Behav. 1994;56:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark AS, Henderson LP. Behavioral and physiological responses to anabolic-androgenic steroids. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:413–436. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMeo AN, Wood RI. Self-administration of estrogen and dihydrotestosterone in male hamsters. Horm Behav. 2006;49:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumartin B, Caillé I, Gonon F, Bloch B. Internalization of D1 dopamine receptor in striatal neurons in vivo as evidence of activation by dopamine agonists. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1650–1661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst M, Romeo RD, Andersen SL. Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: a window into a neural systems model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frye CA, Rhodes ME. Administration of estrogen to ovariectomized rats promotes conditioned place preference and produces moderate levels of estrogen in the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2006;1067:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galvan A. Adolescent development on the reward system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;93:199–211. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillies GE, McArthur S. Estrogen actions in the brain and the basis for differential action in men and women: a case for sex-specific medicines. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(2):155–198. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handa RJ, Kerr JE, DonCarlos LL, McGivern RF, Hejna G. Hormonal regulation of androgen receptor messenger RNA in the medial preoptic area of the male rat. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;39:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00353-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmer PA. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among young male and female athletes: is the game to blame? Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:26–31. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.068924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoseini L, Roozbeh J, Sagheb M, Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A. Nandrolone decanoate increases the volume but not the length of the proximal and distal convoluted tubules of the mouse kidney. Micron. 2009;40:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG., Jr Anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: an emerging disorder. Addiction. 2009;104:1966–1978. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kindlundh AM, Lindblom J, Bergström L, Wikberg JE, Nyberg F. The anabolic-androgenic steroid nandrolone decanoate affects the density of dopamine receptors in the male rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:291–296. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kindlundh AM, Lindblom J, Nyberg F. Chronic administration with nandrolone decanoate induces alterations in the gene-transcript content of dopamine D(1)- and D (2)-receptors in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;979:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02843-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kindlundh AM, Rahman S, Lindblom J, Nyberg F. Increased dopamine transporter density in the male rat brain following chronic nandrolone decanoate administration. Neurosci Lett. 2004;356:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn C, Johnson M, Thomae A, Luo B, Simon SA, Zhou G, Walker QD. The emergence of gonadal hormone influences on dopaminergic function during puberty. Horm Behav. 2010;58:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauber ME, Lichtensteiger W. Pre- and postnatal ontogeny of aromatase cytochrome P450 messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the male rat brain studied by in situ hybridization. Endocrinology. 1994;135(4):1661–1668. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.4.7925130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesting J, Neddens J, Teuchert-Noodt G. Ontogeny of the dopamine innervation in the nucleus accumbens of gerbils. Brain Res. 2005;1066:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lood Y, Eklund A, Garle M, Ahlner J. Anabolic androgenic steroids in police cases in Sweden 1999–2009. Forensic Sci Int. 2012;10:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meek LR, Romeo RD, Novak CM, Sisk CL. Actions of testosterone in prepubertal and postpubertal male hamsters: dissociation of effects on reproductive behavior and brain androgen receptor immunoreactivity. Horm Behav. 1997;31:75–88. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Packard M, Schroeder J, Alexander G. Expression of testosterone CPP is blocked by peripheral or intra-accumbens injection of α-flupenthixol. Horm Behav. 1998;34:39–47. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parrilla-Carrero J, Figueroa O, Lugo A, García-Sosa R, Brito-Vargas P, Cruz B, Rivera M, Barreto-Estrada JL. The anabolic steroids testosterone propionate and nandrolone, but not 17alpha-methyltestosterone, induce conditioned place preference in adult mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romeo RD, Diedrich SL, Sisk CL. Estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in prepubertal and adult male Syrian hamsters. Neurosci Lett. 1999;23; 265(3):167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roselli CE. The effect of anabolic-androgenic steroids on aromatase activity and androgen receptor binding in the rat preoptic area. Brain Res. 1998;792:271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salas-Ramírez KY, Montalto PR, Sisk CL. Anabolic androgenic steroids differentially affect social behaviors in adolescent and adult male Syrian hamsters. Horm Behav. 2008;53:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato SM, Schulz KM, Sisk CL, Wood RI. Adolescents and androgens, receptors and rewards. Horm Behav. 2008;53:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schepis TS, Adinoff B, Rao U. Neurobiological processes in adolescent addictive disorders. Am J Addict. 2008;17:6–23. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schramm-Sapyta NL, Pratt AR, Winder DG. Effects of periadolescent versus adult cocaine exposure on cocaine conditioned place preference and motor sensitization in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schramm-Sapyta NL, Walker QD, Caster JM, Levin ED, Kuhn CM. Are adolescents more vulnerable to drug addiction than adults? Evidence from animal models. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma S, Fulton S. Diet-induced obesity promotes depressive-like behaviour that is associated with neural adaptations in brain reward circuitry. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;37:382–389. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shughrue P, Scrimo P, Lane M, Askew R, Merchenthaler I. The distribution of estrogen receptor-beta mRNA in forebrain regions of the estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mouse. Endocrinology. 1997;138(12):5649–5652. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva WI, Maldonado HM, Lisanti MP, Devellis J, Chompré G, Mayol N, Ortiz M, Velázquez G, Maldonado A, Montalvo J. Identification of caveolae and caveolin in C6 glioma cells. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spear LP, Horowitz GP, Lipovsky J. Altered behavioral responsivity to morphine during the periadolescent period in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1982;4:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(82)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi K, Hallberg M, Magnusson K, Nyberg F, Watanabe Y, Långström B, Bergström M. Increase in [11C] vorozole binding to aromatase in the hypothalamus in rats treated with anabolic androgenic steroids. Neuroreport. 2007;18:171–174. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328010ff14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Triemstra JL, Sato SM, Wood RI. Testosterone and nucleus accumbens dopamine in the male Syrian hamster. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahlstrom D, Collins P, White T, Luciana M. Developmental changes in dopamine neurotransmission in adolescence: behavioral implications and issues in assessment. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walf AA, Rhodes ME, Meade JR, Harney JP, Frye CA. Estradiol-induced conditioned place preference may require actions at estrogen receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:522–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witzmann FA. Soleus muscle atrophy in rats induced by cast immobilization: lack of effect by anabolic steroids. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood RI. Reinforcing aspects of androgens. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]