Abstract

Background:

The aim of the present research was to describe and compare the oral health of children with cerebral palsy (CP) with the normal children in India.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty children with CP of the age range 7-17 years and fifty normal children were selected for the study. An oral examination was carried out and decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT) index, oral hygiene index-simplified (OHI-S) index, Angles malocclusion were charted along with other significant dental findings. Data were analyzed using Student's t-test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test.

Results:

The mean dmft/DMFT of the CP group was 4.11 ± 2.62, while that of controls was 2.95 ± 2.75, which showed higher caries prevalence in the CP group. There was a significant association between the dmft/DMFT (P = 0.03), OHI-S (P = 0.001), and Angles Class 2 malocclusion and CP.

Conclusions:

Cerebral palsy group had higher caries, poor oral hygiene and Class 2 malocclusion when compared to controls primarily because of their compromised general health condition and also less dental awareness. Effort should be made for better organization of preventive dental care and promoting dental health of this challenged population.

Keywords: Caries, cerebral palsy, malocclusion, oral health

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is a part of holistic health. It affects one's communication, appearance and performance. However, it is the most unattended health need especially in those people who are mentally challenged.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is defined as a group of disorders of development of movement and posture, causing activity limitations that are attributable to nonprogressive disturbances, which have occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain.[1] It has a prevalence rate of approximately 2-2.5 and 3.3/1000 children worldwide and India respectively.[2] CP causes structural changes in the oro-facial region and para-functional oral habits associated with neuromuscular deficits giving rise to an array of dental disorders ranging from dental caries and periodontal disease, malocclusion, drooling, bruxism to developmental enamel defects have been reported.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

Cerebral palsy can be classified based on severity as: (a) Mild CP - patient ambulates without assistance, (b) moderate CP - medications, bracing, and adaptive equipment to ambulate are required, and severe - mobility only on a wheelchair.

There are few studies conducted in India to assess the oral health and the need for oral care in the mentally disabled population. Significant variability exists in data related to the incidence of dental caries among children with CP with some authors reporting higher,[8,10] lower or equal[11] prevalence than the healthy children.

The aim of this study is to compare the oral health of children with CP with the normal children. The primary objectives were to compare the oral health of children with CP to normal children along with gender-wise and age-wise comparison and secondary objective was to correlate it to the mental disability of the patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort

Prior to the start of the study ethical clearance of the protocol was obtained from Ethical Committee of the Institutional Review Board (Jodhpur Dental College General Hospital). Permission in the form of written consent of their voluntary participation in the study was obtained from schools and parents/guardians of all the children.

Cerebral palsy group included, children of both the genders of the age range 7-17 years in various special care centers in Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Children having mental disorder other than CP was excluded the study. Control group comprised of the same number of children who were age (±3 months) and gender - matched, corresponding to the study group, from mainstream schools of the same community.

The study was carried out in two stages; in the first stage the consent forms and data requisition regarding the demographic details of the children through questionnaire was distributed to the parents/guardians, in the second stage oral examination was carried out on an informed predetermined date. Initially, 63 CP children were approached and given the consent forms, of which two did not want to participate in the study, eight children were sick and four were unavailable on the day of examination, so were not excluded from the study leaving a total of 50 CP children. The study was carried out with a total of 100 subjects, 50 with CP and 50 normal children.

Methodology

Oral examination was carried out by one examiner using sterile dental mouth mirror and probe. This examiner was an experienced endodontist previously well trained with diagnosis of such condition. The intra-examiner reliability was established by re-examination of 10 (10% of the sample) that was 0.91.

The oral health status was evaluated using World Health Organization (WHO) criteria 2013 for dental caries using the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft/DMFT) index. In dmft/DMFT caries prevalence is numerically expressed by calculation of the number of carious, missing and filled teeth in an individual. The overall values of dmft and DMFT were evaluated separately and together by the sum of d + m + f/D + M + F. The scores were given and the severity of dental caries was expressed based on previously proposed values:[12] dmft/DMFT 0 = caries free; dmft/DMFT 1-2 = low severity; dmft/DMFT 3-4 = moderate severity or dmft/DMFT ≥ 5 high severity. If retained deciduous tooth was present, the caries status of only the permanent was recorded, as per WHO guidelines.

Oral hygiene status was assessed using the simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S) of Greene and Vermillon with a total score of 6. On obtaining an index score was 0-0.9, oral hygiene was classified as good, 1-1.9 (fair) and 2.0 and above (poor).[13] Thickness plaque in the cervical area of teeth was checked to calculate the plaque index. The malocclusion was classified as Class 1, Class 2 or Class 3 type as given by Angle. This classification is based on the relationship of the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar and the buccal groove of the mandibular first molar.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was also recorded as it influences on the incidence and prevalence of various health related conditions in terms of the accessibility, affordability, acceptability and actual utilization of various health facilities. Modified Prasad's classification 2013[14] based on a per capita monthly income was used for the calculation SES as it can be applied to both urban and rural population and is simple to calculate. They were assigned the following groups: (a) Upper - Class 1, (b) middle - Class 2 and 3 and lower - Class 4 and 5.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software using Student's t-test, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA test.

RESULTS

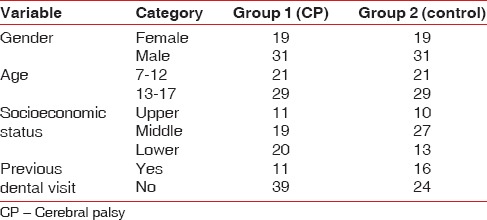

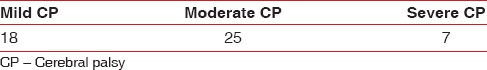

There were 38 (38%) females and 62 (62%) males, aged 7-17 years [Table 1]. Parents of the majority of the subjects (46%) were of middle socioeconomic background [Table 1]. Only 27 (27%) had visited the dentist previously, comprising 11 (22%) of the CP group and 16 (32%) of the control group [Table 1]. Out of the 50 CP children 18 children with mild CP could ambulate without assistance, 25 with moderate CP could ambulate with medications, bracing, and adaptive equipment and 7 with severe CP were mobile only on a wheelchair [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

Table 2.

Topographic distribution of CP cases

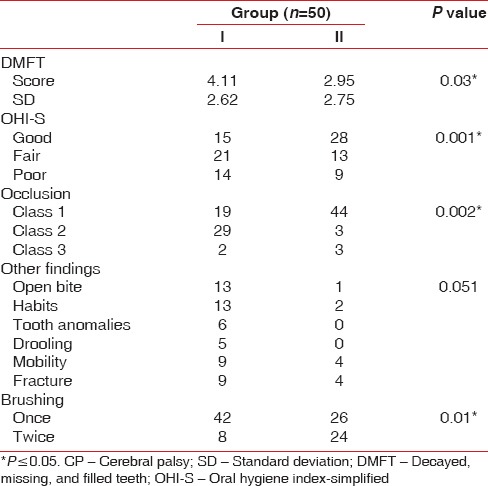

The mean dmft/DMFT of the CP group was 4.11 ± 2.62, while that of controls was 2.95 ± 2.75 [Table 3]. Group-wise comparison [Table 3] of the dmft/DMFT scores by applying Student's t-test found statistically significant (P = 0.03) differences between the two groups. Comparison of OHI-S scores by Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA, showed a significant difference in subjects belonging to good category of OHI-S. Similarly, significant difference in the type of occlusion was also observed by Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA and the post-hoc pair-wise comparison showed only Class 2 occlusion had a significant difference. No significant difference was found between other findings.

Table 3.

Group-wise comparisons of oral health status and brushing habits among normal and CP subjects

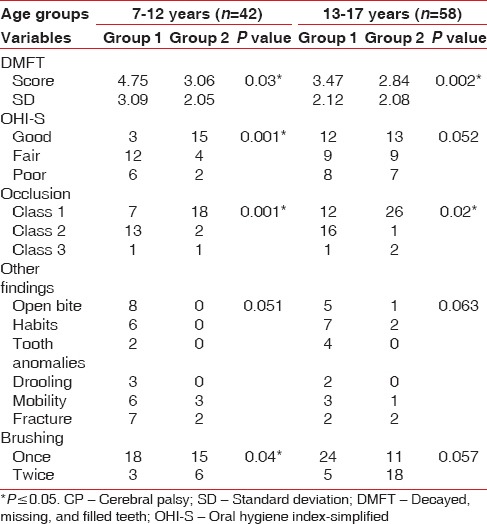

Age-wise comparison [Table 4] of the CP Group and control group found statistically significant difference (P = 0.03 and P = 0.002) in dmft/DMFT and (P = 0.001 and P = 0.02) occlusion for 7-12 years and 13-17 years age groups, respectively. OHI-S scores and brushing were found to be statistically significant in 7-12 years age group with a P value of 0.001 and 0.04 respectively.

Table 4.

Age-wise comparisons of oral status and brushing habits among CP subjects

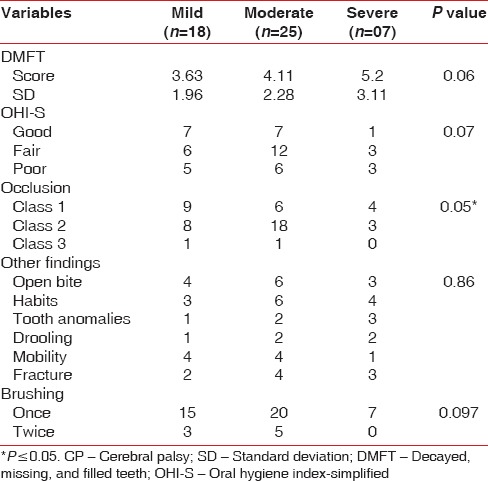

Severity-wise comparison [Table 5] among the CP group showed no significant differences between any of the variables within the group (mild, moderate, and severe).

Table 5.

Severity-wise comparison of oral health status and brushing habits among CP subjects

Nine (18%) children of CP group and 4 (8%) in the control group had fractured teeth. Anterior open bite was also more prevalent (26%) in the CP group versus the (2%) controls, but was not statically significant. Oral habits of tongue thrusting and lip sucking were also observed in CP group 13 (26%) in CP group and 2 (4%) in the control group. Teeth anomalies like microdontia and hypoplasia were found in 6 CP children.

DISCUSSION

Oral health or disease has a direct impact on an individual's well-being and functioning, especially in children, so any society desires to provide a good quality of life for children has to understand their requirements including those with special needs. There is a paucity of studies concerning oral health status among special health group like CP in India. This case–control study compared the oral health among children with CP to those of the mainstream schools. The information gathered from the study could be used for better planning and promoting the oral health of this special need group.

In accordance with previous studies,[8,15] CP group showed a higher mean dmft/DMFT than controls. Another study on dental caries and oral hygiene among children of Bombay, reported that the prevalence and severity of dental caries were highest in CP group.[16] In contrast another author[17] found no significant difference in caries but found more extracted and untreated decay and less poor quality restoration in CP children. This could be because of food stagnation in the buccal and labial sulci due to their poor masticatory muscular control and diet rich in soft mushy cariogenic food which is easy to swallow. Another contributory factor is the sweetened medications (carbamazipine most commonly and sometimes even herbal formulation) given to them to control seizures and other medical problems. The prescribed anticonvulsants are sweetened, highly viscous and used at night, which enhances the progression of dental caries.[18]

Dental attendance was particularly low in the CP group only 22% had ever visited a dentist since birth. Furthermore, the reasons for the visit were predominantly specific problem oriented and rarely for a preventive procedure. One reason could be that most of subjects 40% were from a lower socioeconomic background, and their oral health needs had to compete with other health needs. Nevertheless, periodic dental checkup should be encouraged, so that oral diseases can be prevented in these children.

Only 30% of the CP children had good oral hygiene, which was much lower than the control group (56%). Similar results with poor oral hygiene in individuals with CP have also been reported by many authors mostly due to difficulty in tooth brushing.[8,19] Age-wise comparison shows improvement in oral hygiene with age, which could be due to learning ability of the children with practice, improvement in motor control with age and lesser dependence on caregivers for brushing.

Tooth brushing twice daily was found only in 8 children from the CP group. Children from both the groups used manual brushes with toothpaste for brushing. Children with CP more frequently required assistance, while brushing specially those who lacked dexterity (severe CP). Most of the parents were unaware of the recommended brushing methods, other oral hygiene practices and electric tooth brushes. A randomized controlled trial on CP patients found significant improvement in plaque levels and gingival health when an electric toothbrush was used.[20] Modifications in brush handle length and size have also been shown to improve cleaning efficiency in these.[21]

Angles Class 2 malocclusion was seen in (58%) of children with CP which was statistically significantly higher than the control group. The abnormal alignment of the tongue, lips and cheeks along with oral habits could be responsible for it. In a study of Greek children, the highest rate of malocclusion was observed in children with CP.[22] Another study showed a significantly higher DMFS index, plaque index and a higher percentage of malocclusion in children with CP.[8]

Drooling was seen five children with CP, which is not related to hyper salivation, but rather due to swallowing defect.[23] Difficulties in moving saliva to the throat is due to the misalignment of teeth and the lack of control of the muscles within the mouth. It is worsened by a lack of head control, poor posture, lack of sensation around the mouth, impaired concentration.

The absence of significant difference of other variables between the age groups and severity groups could be due to the small sample size and unequal distribution between groups.

Limitations

There was difficulty obtaining permission from the school authorities. There was some difficulty getting some children to cooperate. Generalizability of the study result has to be considered with caution due to the small sample size. Further state and nationwide studies on this special population are warranted to unearth the real associations of certain variables with oral conditions. The effect of medications on the oral environment could have biased the results to some extent, so further studies are warranted to delineate the exact oral diseases and its contributing factors among CP patients.

CONCLUSION

The study showed that children suffering from CP have poor oral hygiene when compared to normal children. This is primarily because of their condition and also because children suffering from CP usually do not seek the services of a dental professional. Effort should be made to spread the awareness and importance of oral health among these children and their family because everyone deserves the opportunity of good oral health and hygiene.

Future trends

Awareness studies could be conducted among the parents of special children to understand their knowledge and attitude toward the oral healthcare needs of their children. The same study could also be conducted between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized palsied children.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scully C, Cawson RA. Medical Problems in Dentistry. 5th ed. Elsevier: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. Neurological disorders I: Epilepsy, stroke and craniofacial neuropathies; pp. 297–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odding E, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: Incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:183–91. doi: 10.1080/09638280500158422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty NJ. A review of cerebral palsy for the oral health professional. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.12.001. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin X, Wu W, Zhang C, Lo EC, Chu CH, Dissanayaka WL. Prevalence and distribution of developmental enamel defects in children with cerebral palsy in Beijing, China. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:23–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guare Rde O, Ciampioni AL. Prevalence of periodontal disease in the primary dentition of children with cerebral palsy. J Dent Child (Chic) 2004;71:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guaré Rde O, Ciamponi AL. Dental caries prevalence in the primary dentition of cerebral-palsied children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2003;27:287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.dos Santos MT, Masiero D, Simionato MR. Risk factors for dental caries in children with cerebral palsy. Spec Care Dentist. 2002;22:103–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2002.tb01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues dos Santos MT, Masiero D, Novo NF, Simionato MR. Oral conditions in children with cerebral palsy. J Dent Child (Chic) 2003;70:40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du RY, McGrath C, Yiu CK, King NM. Oral health in preschool children with cerebral palsy: A case-control community-based study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:330–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Camargo MA, Antunes JL. Untreated dental caries in children with cerebral palsy in the Brazilian context. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:131–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen LA. Philadelphia, PA: International Association of Dentistry for the Handicapped Philadelphia; 1988. Caries among children with cerebral pals. Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the International Association of Dentistry for the Handicapped; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.5th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys – Basics Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudala SR, Arlappa N. Updated prasad SES classification. Int J Res Dev Health. 2013;1:26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oredugba FA. Comparative oral health of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy and controls. J Disabil Oral Health. 2011;12:81–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhavsar JP, Damle SG. Dental caries and oral hygiene amongst 12-14 years old handicapped children of Bombay, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 1995;13:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope JE, Curzon ME. The dental status of cerebral palsied children. Pediatr Dent. 1991;13:156–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siqueira WL, Santos MT, Elangovan S, Simoes A, Nicolau J. The influence of valproic acid on salivary pH in children with cerebral palsy. Spec Care Dentist. 2007;27:64–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2007.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dos Santos MT, Nogueira ML. Infantile reflexes and their effects on dental caries and oral hygiene in cerebral palsy individuals. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:880–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bozkurt FY, Fentoglu O, Yetkin Z. The comparison of various oral hygiene strategies in neuromuscularly disabled individuals. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;5:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damle SG, Bhavsar JP. Plaque removing efficacy of individually modified toothbrushes in cerebral palsy children. ASDC J Dent Child. 1995;62:279–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsea AG, Karidis AG, Donta-Bakoyianni C, Spyropoulos ND. Oral health status in Greek children and teenagers, with disabilities. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2001;26:111–8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.1.705x15693372k1g7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tahmassebi JF, Curzon ME. The cause of drooling in children with cerebral palsy – Hypersalivation or swallowing defect? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:106–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]