Abstract

Gingival recession along with reduced width of attached gingiva and inadequate vestibular depth is a very common finding. Many techniques have been adopted in order to treat such defects and obtain predictable root coverage. Several graft procedures are used to obtain the coverage, but they have not been able to deliver predictable and satisfactory results (except connective tissue graft). Some of them also resulted in the secondary surgical site that was very uncomfortable for the patients. There was an intense need for a technique that provides not only good and predictable root coverage, but also reduces the need for secondary surgical site. Hence, this paper describes a single stage technique for increasing the width of attached gingiva and root coverage by using the periosteal pedicle graft.

Keywords: Attached gingiva, periosteal fenestration, periosteal pedicle flap, single stage technique, vestibular deepening, width of attached gingival

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal plastic surgery is defined as a “surgical procedure performed to correct or eliminate anatomic, developmental, or traumatic deformities of gingival or alveolar mucosa.”[1] Attached gingiva is considered of utmost important as it plays an important role of beholding the gingiva at its position. Hence, presence of “adequate” width of attached gingiva is considered important for the maintenance of marginal tissue health and for the prevention of continuous loss of connective tissue attachment (Naber's 1954).

Gingival recession is defined as the displacement of the gingival marginal tissue apical to the cementoenamel junction. A narrow zone of gingiva is believed to be insufficient to protect the periodontium from any type of injury resulting from friction forces generated during mastication and pull forces created by the muscles of the adjacent alveolar mucosa on the gingival margin.[2] Also, it was believed that an “inadequate” zone of gingiva would result in accumulation of subgingival plaque formation because of the improper margin closure resulting from the movability of the marginal gingiva and also favor attachment loss and softtissue recession because of less tissue resistance to apical spread of plaque-associated gingival lesion. Thus, it finally results in reduced vestibular depth due to apical displacement of gingival margin, which further on worsens the condition.[3] Tooth hypersensitivity, inability to perform proper oral hygiene procedures or poor aesthetics are the problems faced by a patient having recession. If not treated in time it may lead to further complications such as root caries, cervical abrasions, and chemical erosions.

Hence, in order to treat such problems mucogingival surgery is required. Successful coverage of exposed roots for esthetic and functional reasons has been the objective of various mucogingival procedures. The purposes of developing new techniques are to increase predictability and to reduce patient discomfort and the number of surgical sites, together with the need to satisfy the patient's aesthetic demands, which include the final color and tissue blend of the grafted area. Several graft procedures are used to obtain the coverage, but they have not able to deliver predictable and satisfactory results (except connective tissue graft). Some of them also resulted in secondary surgical site that was very uncomfortable for the patients. Hence, there was an intense need for a graft that has its own blood supply, which can be harvested adjacent to the recession defect in sufficient amounts without requiring any second surgical site, and has the potential for promoting the regeneration of lost periodontal tissue, is a long-felt need. The adult human periosteum is highly vascular and is known to contain fibroblasts and their progenitor cells (i.e. osteoblasts) and stem cells. In all age groups, the cells of the periosteum retain the ability to differentiate into fibroblasts, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and skeletal myocytes. The tissues produced by these cells include cementum with periodontal ligament fibers and bone;[4] in addition, the presence of the periosteum adjacent to gingival recession defects occur in sufficient amounts make it a suitable graft.

Mahajan has described one such new procedure for recession coverage by utilizing the periosteal pedicle graft.[5] This graft utilizes the osteogenic potential of the periosteum which is due to its highly vascular nature, presence of fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and stem cells. The present case report describes a technique where the vestibular deepening was carried out with the fenestration technique and the layer of periosteum was incised and was used as a pedicle graft for the treatment of a single tooth gingival recession.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old male patient reported with the chief complaint of unesthetic appearance of his front lower tooth [Figure 1]. On examination, it was found that 5 mm deep and 3 mm wide Class II gingival recession (Miller, 1985) was present on the lower right central incisor [Figures 2 and 3]. The vestibular depth and the width of attached gingival were also inadequate in the region. There was no mobility associated with the tooth and fremitus test was negative. He was nonsmoker and systemically healthy.

Figure 1.

Class II Miller's recession in lower left central incisor

Figure 2.

5 mm length of recession

Figure 3.

3 mm width of recession

For increasing vestibular depth and root coverage, vestibular deepening with fenestration and root coverage using the periosteal pedicle graft was planned. The patient was explained about the surgery and a signed informed consent was taken by him. A general assessment of the patient was made through his history, clinical examination and routine laboratory investigations.

In the first sitting, the patient received Phase-I therapy, which included oral hygiene instructions and scaling with ultrasonic and root planning with hand instruments. The patient was recalled after 1 week for the surgery.

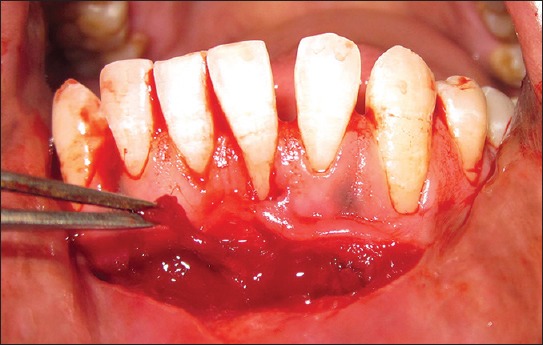

After assuring surgical asepsis, a preprocedural rinse with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate was accomplished. Local anesthesia was first administered bilaterally by using a mental nerve block. Later, a horizontal incision was made using a no. 15 surgical blade at the mucogingival junction retaining all of the attached gingiva [Figure 4]. A split-thickness flap was reflected sharply, dissecting muscle fibers and tissue from the periosteum.

Figure 4.

Vestibular incision placed extending from canine to canine exposing the periosteum

The recipient site preparation included two incisions. First, intracrevicular incision and a second incision made parallel and apical to the first incision [Figure 5]. The incisions were followed by split-thickness dissection of the facially located tissue up to the level of the vestibular incision so as to create a tunnel [Figure 6]. The exposed root surface was root planed.

Figure 5.

Preparation of recipient site

Figure 6.

Tunnel created at the recipient site

A strip of periosteum was then removed at the level of the mucogingival junction, causing a periosteal fenestration exposing the bone. The care was taken not to remove the periosteal strip completely and to leave it pedicled to the bone and the rest of the surrounding periosteum at the lateral end [Figure 7]. The pedicled periosteal donor tissue was then moved vertically toward the recession area, passing through the tunnel [Figure 8]. At repositioning, the osteoperiosteal portion was closely adapted to the recipient site by pressing for 3 min and then Amacrylate tissue adhesive was used instead of sutures for holding the donor tissue at its placed position.

Figure 7.

Periosteum scraped to create the fenestration, periosteum remains attached to bone at one end

Figure 8.

Pedicled periosteal graft placed over the area of recession through the prepared tunnel

Periodontal dressing Coe Pak (De Trey/Denstply, Konstanz, Germany) was applied over the operated area covering the exposed bone. The patient was prescribed with antibiotic therapy, that is, amoxicillin 500 mg, thrice a day and analgesic, that is, ibuprofen 400 mg twice a day for 5 days.

Tooth-brushing was discontinued for the first 2 weeks at the surgical site and 0.2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse was instructed until 4 weeks after surgery. Coepak was removed 10 days after the surgical procedure and the patient was asked to maintain meticulous oral hygiene. Healing had proceeded uneventfully.

In 3 weeks, healing was nearly complete, with minimal postoperative discomfort to the patient. At 6 months postoperative, root coverage was nearly 100% of the recipient site, with minimal probing depths, no inflammation, and a favorable esthetic result [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Six months postoperative view showing complete root coverage

DISCUSSION

Several surgical techniques have been developed to correct the gingival recession defects, but they have failed to provide predictable and satisfactory results to the patients. The purposes of developing new techniques are to increase predictability and to reduce patient discomfort, number of surgeries and the number of surgical sites, together with the need to satisfy the patient's esthetic demands, which include the final color and a tissue blend of the grafted area.[4] The goals for surgical treatment of gingival recession include reducing root sensitivity, minimizing cervical root caries, increasing the zone of attached gingiva, and improving esthetics.

The ideal and most important requirement of graft is that it should have its own blood supply and the potential for promoting the regeneration of lost periodontal structures. The adult human periosteum is highly vascular and is known to contain fibroblasts and their progenitor cells and stem cells. The cells of the periosteum retain the ability to differentiate into fibroblasts, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and skeletal myocytes throughout life. The tissues produced by these cells include cementum with the periodontal ligament fibers and bone.[6] Due to its osteogenic potential and presence adjacent to gingival recession defects in sufficient amounts, makes periosteum suitable for a graft. The adult human periosteum is highly vascular and comprises of at least two layers, an inner cellular layer or cambium layer and outer fibrous layer.[7,8,9] Due to the osteogenic potentiality of periosteum, it has been considered as a grafting material for the repair of bone and joint defects.

Only few limited studies are available in literatures that have mentioned the use of periosteum for the treatment of gingival recession defects successfully. Mahajan and Harshavardhana et al. have reported the successful treatment outcome by using the periosteal pedicle graft for treating gingival recession defects.[5,10,11] Lekovic et al. and Kwan et al. used periosteum as a barrier membrane for the treatment of periodontal defects in their studies.[12,13,14] A recent study reported that periosteal cells release a vascular endothelial growth factor.[15] According to LoMelcher, such periosteal activation may result in the differentiation of cells portraying the ability to produce cementum and connective tissue and may lead to enhanced cementogenesis and fiber reattachment to tooth structure, demineralized in situ.[15] An increase in gingival height independent of the number of millimeters is considered a successful outcome of gingival augmentation procedures.[16] Histologic studies carried out by Wilderman and Wentz have shown connective tissue attachment of the replaced tissues to previously denuded root surfaces.[17] Thus, it seems obvious that some kind of connective tissue reattachment is a possibility with the osteostimulated repositioned periosteal flap. The success of the technique may be due to the high vascularity of the graft, the single surgical site, patient comfort, reduced intraoperative time and minimum postoperative complications and the low cost of treatment.

The present case report successfully demonstrated a single stage technique for vestibular deepening and recession coverage utilizing the periosteum as autograft for the treatment of gingival recession defect. An adequate attachment occurred after the use of the pedicled periosteal graft in the treatment of denuded root. An increase in the width of keratinized gingiva occurred after the combined vestibular deepening procedure.

Throughout the follow-up period, the patient maintained good plaque control and hence the plaque did not have any influence on the final stable attachment that was achieved. Esthetic outcomes were assessed using the root coverage esthetic score (RES).[18] This score evaluates five variables:

Level of the gingival margin – 6

Marginal tissue contour – 1

Softtissue texture – 1

Mucogingival junction alignment – 1

Gingival color – 1.

Root coverage aesthetic score for the presented case was 10.

The limitation of the technique remains that it is technique sensitive and it can he used only for single tooth recessions with an inadequate width of attached gingiva. However, the lack of a second surgical site and good postoperative results achievable makes it a viable procedure for Miller's Class II recessions with an inadequate width of attached gingiva. The technique used here is proposed to give better results than the previous techniques described in literature owing to the dual blood supply, that is, from the pedicled periosteuim and second from the periosteum present below the gingival mucosa used to create the tunnel.

CONCLUSION

The present case reported an excellent postoperative outcome showing complete coverage of exposed root surface and increase in width of attached gingiva. RES for the presented case was 10. The advantages of periosteal pedicled graft are:

The periosteal pedicle graft does not require a second surgical site to obtain a donor tissue

Vestibular deepening and root coverage in a single procedure

Sufficient amount of tissue can be obtained from adjacent to the defect

Dual blood supply to the periosteum

Less surgical trauma

Less postoperative complications

Better patient satisfaction.

Thus, it can be concluded that a periosteal pedicled graft, when combined with a fenestration technique for vestibular deepening, offers a successful and viable alternative for the coverage of localized gingival recessions with an inadequate width of attached gingiva.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takei H, Azzi R, Han T. Periodontal plastic and esthetic surgery. In: Carranza FA, editor. Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1005–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ochsenbein C. Newer concept of mucogingival surgery. J Periodontol. 1960;31:175–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennstrom J, PiniPrato GP. Mucogingival therapy periodontal plastic surgery. In: Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang N, editors. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 4th ed. Copenhagen: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2003. pp. 576–650. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouchard P, Malet J, Borghetti A. Decision-making in aesthetics: Root coverage revisited. Periodontol 2000. 2001;27:97–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2001.027001097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan A. Periosteal pedicle graft for the treatment of gingival recession defects: A novel technique. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:250–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwell H, Fiorellini J, Giannobile W, Offenbacher S, Salkin L, Townsend C, et al. Oral reconstructive and corrective considerations in periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1588–600. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.9.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhaskar SN. 11th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002. Orbans™ Histology and Embryology; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon TM, Van Sickle DC, Kunishima DH, Jackson DW. Cambium cell stimulation from surgical release of the periosteum. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:470–80. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youn I, Suh JK, Nauman EA, Jones DG. Differential phenotypic characteristics of heterogeneous cell population in the rabbit periosteum. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:442–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan A. Treatment of multiple gingival recession defects using periosteal pedicle graft: A case series. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1426–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harshavardhana B, Rath SK, Mukherjee M. Periosteal pedicle graft – A new modality for coverage of multiple gingival recession defects. Indian J Dent Adv. 2013;5:1139–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lekovic V, Kenney EB, Carranza FA, Martignoni M. The use of autogenous periosteal grafts as barriers for the treatment of Class II furcation involvements in lower molars. J Periodontol. 1991;62:775–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.12.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lekovic V, Klokkevold PR, Camargo PM, Kenney EB, Nedic M, Weinlaender M. Evaluation of periosteal membranes and coronally positioned flaps in the treatment of Class II furcation defects: A comparative clinical study in humans. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1050–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwan SK, Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Klokkevold PR, Kenney EB, Nedic M, et al. The use of autogenous periosteal grafts as barriers for the treatment of intrabony defects in humans. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1203–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.11.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melcher AH. On the repair potential of periodontal tissues. J Periodontol. 1976;47:256–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.5.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wennström JL, Zucchelli G. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures? A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilderman MN, Wentz FM. Repair of a dentogingival defect with a pedicle flap. J Periodontol. 1965;36:218–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cairo F, Rotundo R, Miller PD, Pini Prato GP. Root coverage esthetic score: A system to evaluate the esthetic outcome of the treatment of gingival recession through evaluation of clinical cases. J Periodontol. 2009;80:705–10. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]