Abstract

Background

Kidney transplantation rates in the United States are lower among African-Americans than among Whites. Well-documented racial disparities in access to transplantation explain some, but not all, of these differences. Prior survey-based research suggests that African-American dialysis patients are less likely than Whites to desire transplantation, but little research has focused on an in-depth exploration of preferences about kidney transplantation among African-Americans. Thus, the purpose of the study was to explore preferences, and compare patients’ expectations about transplantation with actual status on the transplant list.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with sixteen African-Americans receiving chronic hemodialysis. We analyzed the interviews using the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. We also reviewed the dialysis center's transplant list.

Results

Four dominant themes emerged: 1) Varied desire for transplant; 2) Concerns about donor source; 3) Barriers to transplantation; 4) Lack of communication with nephrologists and transplant team. A thread of mistrust about equity in the transplantation process flowed through themes 2-4. In 7/16 cases, patients’ understanding of their transplant listing status was discordant with their actual status.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that many African-Americans on hemodialysis are interested in kidney transplantation, but that interest is often tempered by concerns about transplantation, including misconceptions about the risks to recipients and donors. Mistrust about equity in the organ allocation process also contributed to ambivalence. The discordance between patients’ perceptions of listing status and actual status suggests communication gaps between African-American hemodialysis patients and physicians. Clinicians should avoid interpreting ambivalence about transplantation as lack of interest.

Keywords: qualitative research, kidney transplantation, African-Americans, patient preferences, decision-making

Introduction

Approximately 400,000 Americans with end-stage renal disease currently undergo chronic dialysis,[1] while in 2013, just over 14,000 end-stage renal disease patients received a kidney transplant.[2] More than one-third of dialysis patients in the United States are African-American, a three-fold overrepresentation compared to the general population.[3-5] Transplantation has been shown to increase life expectancy [6, 7] and improve quality of life relative to dialysis.[8, 9] Yet African-American patients are significantly less likely than White patients to receive transplants.[10-17] In part, this reflects a significant racial disparity in access to transplantation - African-American patients who desire kidney transplants receive them less frequently than Whites, even accounting for medical comorbidity, functional status and sociodemographic characteristics.[10, 11, 15, 18] Previous survey research also suggests that African-American dialysis patients may be less likely than Whites to desire transplantation.[10, 11, 19] However, there has been very little research specifically focused on an in-depth exploration of preferences about kidney transplantation among African-Americans on dialysis. Qualitative research is particularly well-suited to provide insight into peoples’ attitudes and preferences about transplantation.[20]

This qualitative study explored preferences about kidney transplantation of African-American hemodialysis patients using semi-structured interviews, and also compared patients’ perceptions of their transplant listing status with their actual status.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

Participants were recruited from an urban dialysis center that serves predominantly African-American patients. We asked the nurse practitioner who managed all hemodialysis patients to identify those who met the following eligibility criteria: African-American, English-speaking, and capable of providing informed consent and participating in the interview.

Eligible patients were approached during dialysis and invited to participate. Thus we assembled a convenience sample of participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board and the dialysis unit's human subjects committee.

Data Collection

All interviews were conducted in-person by one investigator (MWW). A semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the authors’ prior work,[21] clinical experience, and an extensive literature review. The guide included open-ended questions with follow-up prompts to explore participants’ experiences with initiating dialysis, living on dialysis, thinking about the future, and considering transplantation, with a focus on decision-making. The guide was informed by incoming interview data and modified iteratively to gain a deeper understanding of the themes expressed. The interview process was flexible and could be modified to respond to the perspectives and experiences shared by participants.

To supplement our interviews, transplant status was ascertained using the dialysis center's transplant candidate log, which identifies each patient and whether or not s/he is listed for transplant. For patients who are not listed as active candidates, the log specifies the reason (e.g., “not candidate,” “not interested,” “awaiting testing”).

Analysis

All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. NVivo 9.0 (QSR International) was used to aid in organizing and coding data for analysis. We employed a constant comparative method of qualitative data analysis.[22, 23] Coding categories were generated from the data themselves, with initial codes refined iteratively to accommodate new data and insights. Initial codes were rearranged into pattern codes that were reintegrated into a conceptualization incorporating the perspectives of all participants.[24-26] Transcripts were coded independently by two investigators (MWW, ME) who met multiple times to discuss the interviews and modify the coding structure. All discrepancies between coders were resolved through discussion, and consensus was achieved. Additional interviews were conducted until the investigators agreed that thematic saturation had been attained, meaning that no new themes were emerging from the data.[27] To ensure rigor in methodology,[20, 28] we took steps to assure the following principles were satisfied: 1) credibility - by triangulating the qualitative findings with results from our recent survey study;[21] 2) transferability - by considering our findings in the context of previous research; and 3) dependability and confirmability - by using verbatim transcription and including participant quotations to support themes.[28]

Results

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with sixteen African-American dialysis patients, which together yielded over 275 pages of transcript data. We stopped recruitment when analysis suggested thematic saturation. Table 1 shows that participants’ median age was 52.5 years (range 37-86 years), 63% were men, and participants had been on hemodialysis for a median of 2.8 years (range 0.5 – 17 years).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics of African-American Dialysis Patients Interviewed (n=16)

| n (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | |

| Median (range) | 52.5y (37-86) |

| <50 | 7 (44) |

| 50-59 | 5 (31) |

| 60-70 | 3 (19) |

| >70 | 1 (6) |

| Genderb | |

| Male | 10 (63) |

| Diabetesc | |

| Yes | 5 (31) |

| No | 9 (56) |

| Unknown | 2 (13) |

| Duration of Dialysis, yearsc | |

| Median (range) | 2.8y (0.5-17) |

| 1 year or less | 3 (19) |

| More than 1 year to 5 years | 10 (63) |

| More than 5 years | 3 (19) |

Data are provided as sample sizes (percentages) unless otherwise specified. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Data obtained from patient

Data obtained from chart review of the dialysis record

Emergent Themes

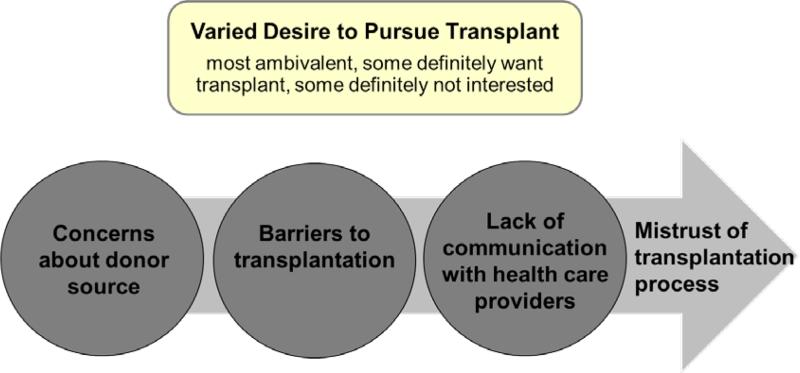

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the four dominant themes that emerged from our data. Represented in the rectangular box, there was varied desire for transplant. The circles below the box represent the other three dominant themes: concerns about donor source, barriers to transplantation, and lack of communication with health care providers. The large arrow intersecting the three circles represents a thread of mistrust about equity in the transplantation process that flowed through each of the themes represented by the circles.

Figure 1. Visual representation of emergent themes.

The arrow intersecting the three circles represents a thread of mistrust about equity in the transplantation process that flowed through each of the themes represented by the circles.

Extracts from interviews are presented to support and illustrate the themes.

Theme 1: Varied Desire for Transplant

Transplantation was on the forefront of many, but not all, participants’ minds. When asked what they felt the future had in store for them, eight participants mentioned “transplant” in the first sentence of their answers – even though the open-ended question had not mentioned that outcome. Some participants definitely wanted a transplant, several definitely did not, but most had both interest in and concerns about transplant, leaving them feeling ambivalent.

For some, receiving a transplant was their central goal. As the interviewer approached one participant, before the interviewer even sat down, he asked, “Do you have a kidney for me?” During the interview, he repeatedly exclaimed, “Just gotta get one. It's that simple.”

A male participant elaborated on the fervent hope for transplant: “I'm just daydreaming about getting that phone call [that there is a kidney for me]. I have a bag packed, you know, like a woman's pregnant...I'm daydreaming about scooping up the bag and running...”

At the other extreme, two participants stated they would never pursue transplant. One 69-year-old woman felt she had too many health problems to consider transplant. The other, an 86-year-old woman, said, “I didn't even ask for that. I figure if there's a transplant, give it to somebody young. Give them an opportunity to have a longer life.”

Patients’ perceptions of the burden of being on dialysis influenced desire for transplant. Some participants described how a transplant would help them, as one participant said, “get some of my lifestyle back.” Most participants talked about the loss of freedom imposed by dialysis and the restrictions that dialysis placed on their lives. The inability to travel, frustrations with dietary restrictions, the magnitude of time spent on dialysis, and the exhaustion that often follows dialysis were commonly described. One participant remarked:

“This is like a part-time job. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday you're on a machine five or four hours... And some days the machine drags all of the life out of you and you just don't want to do nothing.”

On the other hand, a couple of participants reported they were not pursuing transplantation because dialysis was not particularly burdensome. For example, one participant commented, “I'm comfortable with my situation. ...My situation is not as bleak as some people's situation is, so you know, my life is not totally standing still because of me being on dialysis.”

While some patients were certain that they wanted transplant and others were sure they did not, most participants, several of whom had immediately mentioned transplant when asked about the future, were, or had been, ambivalent about transplantation. As one participant shared,

“I finally made the call to set up the appointment for my [transplant] evaluation, which is in a couple of months. I was [totally] against it for a while [because] you go through all the time and expense and work of getting a transplant that may not take, you know, and it may be rejected and after a few years you'll be right back in dialysis. It took me many months, maybe even a year or so to change and one of the reasons I changed was, you know, frankly I'm getting tired of dialysis.”

As exemplified by this quote, a common concern leading to ambivalence was the possibility of transplant rejection or failure. Several participants felt that to go through the arduous transplantation evaluation and surgery and then experience graft failure would be very difficult. One participant explained, “[The transplanted] kidney [can] fail for a number of reasons, and ... they're back on dialysis. And I think from an emotional standpoint that would make it hard to take... for me to go through that process and come back to dialysis.”

Several participants also appeared to believe transplant failure would be fatal: “If I have a transplant and it doesn't take, will I be able to find another donor any time soon or will I be on that list and die before [finding another].”

Theme 2: Concerns about Donor Source

As described in Theme 1, ambivalence about transplantation was common. One source of ambivalence related to patients being conflicted about receiving a kidney from a loved one versus a deceased donor kidney.

Some participants reported that relatives had offered to donate a kidney. However, most were reluctant to accept this offer out of concern that their loved one might develop kidney failure in the future. As one man said:

“A lot of family members are trying to [give] me a kidney, but... I wouldn't want nobody to be in this [situation]... they give me a kidney, they get in a car accident, and they end up damaging their kidney then what? Then... they're sitting looking at the same thing I'm looking at now.”

However, a number of participants spontaneously mentioned strong reservations about deceased donor kidneys. Some voiced concerns about not knowing the age or the medical history of unknown donors, which some believed would affect transplant success. Some participants expressed mistrust about equity in the allocation process. Reflecting on the quality of the kidney he thought he, compared to other recipients, would receive, one participant stated, “I think that I would just get any old kidney, because you agree to take an older person's kidney, or a drug addict's kidney.”

Several participants expressed fears that they might assume the donor's personality. One woman said, “I read something where this person got a heart transplant and they start acting like the person that they got the heart from... Does the same thing happen if you get a kidney?”

Theme 3: Barriers to Transplantation

The vast majority of participants mentioned at least one barrier to receiving a kidney. The most common barrier discussed was the battery of numerous, time-consuming pre-transplantation appointments and tests. As one man explained,

“You gotta see a lot of doctors. You gotta see a psychologist. You gotta see a...heart doctor...Oh God, the list goes on! I see the ear doctor, the tooth doctor. It's not like they just write your name down and put you on the list. It's a process.”

There was often a tone of mistrust as participants described the transplant evaluation process:

[They] wanted test results from 2002. This will blow [your] mind: When I was in my twenties, I had syphilis; [they] wanted proof that I had been treated for syphilis. I'm fifty-six...I'm doing it. They're spinning me, but I'm doing it.”

Other participants spoke more generally about how modern medicine had failed patients with end-stage renal disease, highlighting scientific advances in other areas and for other groups of patients. Reflecting on this, one participant remarked,

“You know, a doctor can turn a man into a woman, but he can't...make a kidney work from somebody else without all of that medicine and sometimes I'm just puzzled by that, you know?”

Theme 4: Lack of Communication with Nephrologists and Transplant Team

Patients expressed frustration about their perceived lack of a relationship with their doctors, particularly during the transplant evaluation process. Some participants believed they were “being overlooked” or that the system was not set up to assist them because they were poor or had HIV. As one participant said,

“The doctors - they're so untouchable...I don't have no relationship with the [transplant] surgeon at all... You want an office visit, not being lined up to be screened [for transplant]. Like you and I talking, that's what I want.”

Another man spoke of longing for a doctor to forge an alliance with him:

“If I was to have one doctor say, ‘Mr. A, we're going to get you a kidney,’ it would make all of the difference in the world, because I would feel like he's in the fight with me. I don't really feel that at all.”

When talking about discussions with their nephrologists, some expressed mistrust connected with race:

“My doctor[s]... be shocked when I asked them, well why is there so many Black people on dialysis and they don't have no real answer for me. I really don't like that. And so then on top of that he only spends ninety seconds with me... I'm like wow, I feel like cattle.”

Actual Transplant Status vs. Perceived Status

In addition to our interviews, we also compared patients’ understanding of their transplant listing status with their actual status recorded on the dialysis center's list. Table 2 shows that only two of the 16 participants interviewed were listed for transplant, and in seven of the 14 non-listed cases, participants’ perceptions of their listing status were discordant with the actual transplant list. As detailed in Table 2, there were many types of discordance, the most common being that patients thought they were listed, but the list said that they were awaiting testing. For example, one woman listed as “inactive, awaiting additional testing,” said, “I'm on the list so I'm waiting for a kidney, so we'll see. And that's gonna come... I'm hoping soon.”

Table 2.

Concordance Between Patients' Perceptions of Transplant Listing Status and Actual Status (n=16)

| n | |

|---|---|

| Patient and Transplant Log Concordant | 9 (56%) |

| Listed for transplant | 2 |

| Not listed for transplant | 7 |

| Patient and Transplant Log Discordant | 7 (44%) |

| Patient thinks listed, log says “awaiting testing” | 3 |

| Patient thinks listed, log says “not interested” | 1 |

| Patient reports ambivalence, log says “not interested” | 1 |

| Patient thinks awaiting insurance, log says “not interested” | 1 |

| Patient thinks awaiting testing, log says “not candidate due to insurance” | 1 |

A man who was listed as “not a candidate because of insurance issues” knew he was not listed currently, but reported that all that stood between him and being listed was him “just picking up the phone and setting up the appointments. That's all.”

Another man listed as “not interested” spoke at length about his desire for a transplant and his frustration with insurance issues that kept him off the transplant list.

One participant perceived a lack of transparency in the listing process stating:“You don't always know [when]... they take you off of the list - they don't always discuss that with you...”

Discussion

This study of African-Americans dialysis patients sought to use qualitative methods to more deeply explore the quantitative finding in previous research that African-American dialysis patients are less likely than Whites to desire kidney transplantation. Our findings highlight that, with the exception of a few participants who definitely did not want transplants, most found dialysis quite burdensome and were interested in transplant. However, while some unambiguously wanted a transplant, for many, that interest was tempered by a number of concerns about transplant, some of which related to mistrust, that left them ambivalent about transplantation. Furthermore, even some of those who wanted a transplant mistrusted the equity of the transplantation evaluation and allocation process.

One common concern described was fear of transplant rejection and, for some, even death after kidney transplantation. Most participants expressed confidence about their prognosis on dialysis, while several voiced a fear of dying following a kidney transplant. This is concerning because prognosis is better for patients who receive transplants.[6-8] Several participants also expressed concern that they would enjoy the experience of freedom from dialysis following transplant, only to have to return to dialysis if it failed – a prospect they considered worse than if they just stayed on dialysis.

Participants also had concerns related to the donor source. Some were hesitant to accept a kidney from a family member, citing a fear of putting a loved one's health at risk, a concern documented in prior studies.[29-33] This fear is inconsistent with scientific evidence, as studies show that risks of donation are extremely low.[34] However, participants also had substantial concerns about deceased donor kidneys, some of which related to mistrust, and thus, many favored receiving a family member's kidney, which differs from several of these prior studies.[30, 32] One such study, by Murray & Conrad,[32] found that the majority of potential transplant recipients preferred a deceased donor kidney, and fewer than 5% would accept a transplant from a family member. In stark contrast to our findings, no participants in their study voiced concerns about deceased donor transplants.[32] These differences may exist because our study focused exclusively on the perspectives of African-Americans, while their study included both African-Americans and Caucasians. Apprehension that a transplant recipient might acquire the personality of the deceased donor was unexpected and not previously documented.

Nearly all participants interested in transplant described barriers. The most common was the time-consuming pre-transplant evaluation process, which previous research indicates may be a greater barrier for African-Americans, who have lower rates of pre-transplant evaluation completion than Whites.[11, 35, 36] Importantly, the tone with which many participants discussed the transplant evaluation and allocation process suggested underlying mistrust in the equity of the process itself, which, within the general population,[37] is more common among non-Whites than Whites. Tests and appointments were often perceived as hoops to jump through, described by some as if they were intentional barriers to transplantation. Participants questioned equity not only at the individual level, but also at the broader societal level, doubting whether adequate resources are dedicated to finding better treatments for end-stage renal disease. Furthermore, participants pointed to the high rates of dialysis among African Americans, which they did not feel nephrologists had adequately explained.

Thus, a thread of mistrust wove through a number of the dominant themes in this study. Mistrust of physicians and concerns about harmful medical experimentation, which exist in the context of the United States’ legacy of racism and unethical medical research practices,[38] are more common among African-Americans than Whites.[39] This mistrust may influence African-American patients’ preferences about kidney source and sense of fairness related to the transplant candidacy and organ allocation process and may also affect doctor-patient communication.

Participants also had a number of misconceptions about transplant in terms of its risk for donors and recipients. This is an important finding because past work[40, 41] has shown that patients who are well-informed about transplant are more likely to be interested in pursuing it, suggesting that some of the reluctance to pursue transplant expressed by our participants may have stemmed from a lack of knowledge and from ineffective doctor-patient communication, not just from a lack of trust. Thus, our findings highlight the need to ensure that patients are receiving accurate information about the risks and benefits of transplant, and that clinicians have the time and training to engage effectively in discussions with patients around transplant preferences. Such discussions should supportively discuss sources of patients’ ambivalence, knowing that mistrust may be a key component.

It is notable that even among this relatively young cohort of African-American dialysis patients, only two participants were active on the transplant list. Disturbingly, almost half of all participants understood their transplant listing status incorrectly compared to the official log maintained by the dialysis unit. This discordance may reflect that important gaps in communication about transplantation[42] and transplant status[21] exist between patients and providers. Most concerning were the instances in which participants thought they were listed for transplant when in fact they were not, or believed they were candidates when they were not. In addition, several participants who voiced interest in transplant during the interview were listed in the log as “not interested,” which may reflect a misunderstanding or fluctuating preferences. Alternatively, the finding may suggest that any ambivalence about transplant, which is known to be more common in African-Americans,[10, 11] can result in someone being mislabeled as “not interested.” There may be similar biases in survey-based research of this issue, as a simple yes/no question about desire for transplant may be less revealing for many African-Americans than Whites, since our in-depth interviews with some patients believed to be “not interested” show that they often are interested but still ambivalent.

While other qualitative studies have explored patients’ perspectives about transplantation,[29-32, 43-46] only a relatively small number have had a sample in which even one-third of participants were African-American,[32, 43, 47] and ours is the first to our knowledge to focus entirely on the perspectives of African-Americans. Some of the themes that emerged from our data were echoed in previous research; however, all of the earlier studies that included a significant proportion of African-Americans were conducted over a decade ago. Therefore, our study provides important insights into the current state of preferences about kidney transplantation among African-Americans on dialysis.

Our study has important limitations. First, the sample was drawn from a single urban academically-affiliated dialysis unit, and our findings may not be transferable to African-Americans in other settings. Second because our sample only included African-Americans, we are unable to conclude whether our findings are unique to African-Americans. Third, information about transplant status was obtained from the log maintained by the dialysis unit, which could contain inaccuracies. Finally, our sample size was relatively small; however, we chose not to enroll additional participants because we had achieved thematic saturation meaning that no new themes were emerging. Despite these limitations, our study makes important contributions to the literature on racial disparities in transplantation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, mistrust and misconceptions about transplant appear to play an important role in decision-making about transplantation by African-American patients on dialysis. One hypothesis bringing these results together is that a self-perpetuating cycle may exist in which racial disparities in access to transplantation[10, 11, 15, 18] contribute to mistrust among African-Americans on dialysis. This mistrust, combined with misconceptions about transplantation, tempers an otherwise strong desire to get off of dialysis, leading to ambivalence about transplantation. This ambivalence may be incorrectly interpreted by providers to be a lack of interest in transplantation, which may make nephrologists and transplant surgeons less likely to offer it, thereby exacerbating disparities in access. The end result of this cascade may be that African-Americans may be less likely to get transplants than their true preferences should indicate.

If our hypothesized self-perpetuating cycle bears out in future studies, it has implications at the levels of both the health care system and the individual clinician, and suggests that we need to intervene in the cycle at both levels. At the system level, our findings suggest that addressing racial disparities in access to transplant, in addition to being critical in its own right, may also be an important component of affecting preferences of African-Americans on dialysis about transplantation. Our findings also suggest that nephrologists and the transplant team need to actively engage African-American dialysis patients in conversations about preferences and barriers to transplantation, including the potential role of mistrust, with the goal of promoting informed patient-centered decision making.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Dr. Wachterman was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards (NRSA) (1F32NR012872-01) from the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Marcantonio was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG035075). The funding sources had no involvement in study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Grant information:

Dr. Wachterman was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards (NRSA) for Individual Postdoctoral Fellows (1F32NR012872-01) from the National Institute of Nursing Research. Dr. Marcantonio was supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG035075).

Footnotes

Contributors: Benjamin Sommers, MD, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health and Patricia Kinser, PhD, WHNP, MSN, RN, Virginia Commonwealth University, School of Nursing provided helpful feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- 1.NIDDK [2014 June 12];Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. 2012 [updated November 15, 2012]; Available from: http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/kustats/

- 2.National Kidney Foundation . Organ donation and transplantation statistics. National Kidney Foundation; 2013. [2014 June 12]. [updated May 21, 2014]; Available from: http://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/factsheets/Organ-Donation-and-Transplantation-Stats.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris K, Agodoa L. Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease1. Kidney Int. 2005;68:914–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris K, Nissenson AR. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1261–70. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powe NR. Let's get serious about racial and ethnic disparities. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1271–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vollmer WM, Wahl PW, Blagg CR. Survival with dialysis and transplantation in patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jun 30;308:1553–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306303082602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999 Dec 2;341:1725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaubel D, Desmeules M, Mao Y, Jeffery J, Fenton S. Survival experience among elderly end-stage renal disease patients. A controlled comparison of transplantation and dialysis. Transplantation. 1995 Dec 27;60:1389–94. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199560120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobbels F, De Bleser L, De Geest S, Fine RN. Quality of life after kidney transplantation: the bright side of life? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007 Oct;14:370–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients' preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999 Nov 25;341:1661–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1148–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjellstrand CM. Age, sex, and race inequality in renal transplantation. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Held PJ, Pauly MV, Bovbjerg RR, Newmann J, Salvatierra O., Jr Access to kidney transplantation: has the United States eliminated income and racial differences? Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2594. doi: 10.1001/archinte.148.12.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggers PW. Racial differences in access to kidney transplantation. Health Care Financ Rev. 1995;17:89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soucie J, Neylan J, McClellan W. Race and sex differences in the identification of candidates for renal transplantation. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1992;19:414. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80947-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasiske BL, Neylan JF, III, Riggio RR, Danovitch GM, Kahana L, Alexander SR, et al. The effect of race on access and outcome in transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:302–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101313240505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purnell TS, Xu P, Leca N, Hall YN. Racial differences in determinants of live donor kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2013 Jun;13:1557–65. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaylin DS, Held PJ, Port FK, Hunsicker LG, Wolfe RA, Kahan BD, et al. The impact of comorbid and sociodemographic factors on access to renal transplantation. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Why hemodialysis patients fail to complete the transplantation process. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:321–8. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Chapman JR, Israni A, Gordon EJ, Craig JC. Qualitative research in organ transplantation: recent contributions to clinical care and policy. Am J Transplant. 2013 Jun;13:1390–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 8;173:1206–14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications; San Fancisco: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Disconvery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Publishing Company; Chicago: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications; Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34:213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods. Notes on transcription. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17:311–4. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Sage Publishers; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in nursing science. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kranenburg L, Zuidema W, Weimar W, Ijzermans J, Passchier J, Hilhorst M, et al. Postmortal or living related donor: preferences of kidney patients. Transpl Int. 2005 May;18:519–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients' concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006 Mar;16:17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pradel FG, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST. Exploring donors' and recipients' attitudes about living donor kidney transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2003 Sep;13:203–10. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray LR, Conrad NE, Bayley EW. Perceptions of kidney transplant by persons with end stage renal disease. ANNA J. 1999 Oct;26:479–83. 500. discussion 484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradel FG, Limcangco MR, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST. Patients' attitudes about living donor transplantation and living donor nephrectomy. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2003;41:849. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Najarian JS, McHugh L, Matas A, Chavers B. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. The Lancet. 1992;340:807–10. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2005;46:734. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1537–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulware L, Troll M, Wang NY, Powe N. Perceived transparency and fairness of the organ allocation system and willingness to donate organs: a national study. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1778–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones J. Bad Blood: The tuskegee syphilis experiment. The Free Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheu J, Ephraim PL, Powe NR, Rabb H, Senga M, Evans KE, et al. African American and non-African American patients' and families' decision making about renal replacement therapies. Qual Health Res. 2012 Jul;22:997–1006. doi: 10.1177/1049732312443427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehrotra R, Marsh D, Vonesh E, Peters V, Nissenson A. Patient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2005;68:378–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulware L, Meoni LA, Fink NE, Parekh RS, Kao W, Klag MJ, et al. Preferences, Knowledge, Communication and Patient-Physician Discussion of Living Kidney Transplantation in African American Families. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1503–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon EJ. Patients’ decisions for treatment of end-stage renal disease and their implications for access to transplantation. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:971–87. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon EJ. “They don't have to suffer for me”: Why dialysis patients refuse offers of living donor kidneys. Med Anthropol Q. 2001;15:245–67. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kranenburg LW, Richards M, Zuidema WC, Weimar W, Hilhorst MT, JN IJ, et al. Avoiding the issue: patients' (non)communication with potential living kidney donors. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Jan;74:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon EJ, Reddy E, Ladner DP, Friedewald J, Abecassis MM, Ison MG. Kidney transplant candidates' understanding of increased risk donor kidneys: a qualitative study. Clin Transplant. 2012 Mar-Apr;26:359–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon EJ. Stability of end-stage renal disease patients' treament decisions. Tansplant Proc. 2001;33:3006. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]