The orbital floor is one of the most common fracture sites, with entrapment of the inferior orbital contents or the inferior rectus muscle in a "trapdoor" fashion. But muscle entrapment is less commonly associated with medial wall blowout fractures. We report a case of an isolated medial orbital wall fracture with entrapment of the medial rectus muscle sheath in a pediatric patient who presented with vasovagal-like symptoms, secondary to oculocardiac reflex.

A 12-year-old boy presented to our emergency room with complaints of repeated episodes of vomiting, dizziness, light-headedness, and nausea. Two days ago, a minor blunt trauma had occurred to the left orbital area. At first an intracranial injury was suspected and subsequent neurological examination together with imaging studies, including computed tomography (CT) were performed. An intracranial injury was not identified; however, a small medial orbital wall fracture was confirmed. Although the position of the adjacent medial rectus muscle was normal, the morphological shape was rounder than the contralateral side (Fig. 1). On the physical examination, the patient complained of discomfort and dizziness with left lateral side gazing. And diplopia as well as aggravated nausea and vomiting consistent with increased vagal tone. The patient underwent immediate surgical exploration of the medial wall fracture, with a transcaruncular approach to release the entrapped tissue (Fig. 2). The incarcerated medial rectus muscle sheath was identified intraoperatively and freed by a periosteal elevator. The herniated intraorbital contents were then reduced and a forced duction test was performed, and then the wound was closed primarily. The initial symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and dizziness markedly disappeared after the day of the surgery. Two months later, there was full range of extraocular muscle movement, and discomfort or dizziness were not reported (Fig. 3).

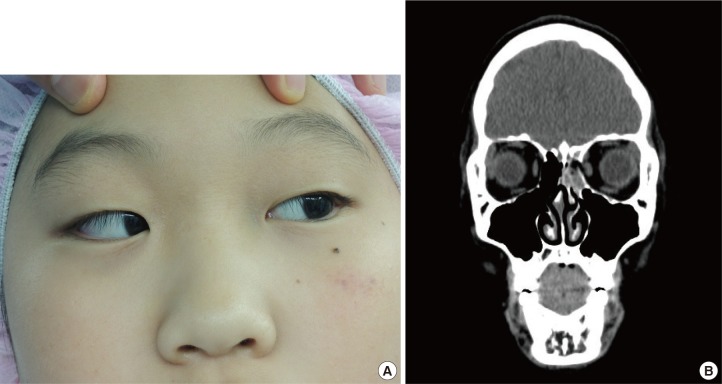

Fig. 1. A 12-year-old boy was identified to have a medial orbit wall fracture in the left orbit. (A) There was no significant soft tissue injury in the periorbital area with a relative quiet eye. The patient was unable to open his eyes fully as result of nausea and vasovagal symptoms, so the physician should hold upper eyelid for examination. The patient showed mild limitation of abduction in the left eye with increased dizziness and nausea. (B) A small isolated medial orbital wall fracture of left orbit with slightly rounded medial rectus muscle was revealed in the computed tomography scan views.

Fig. 2. Surgical release of the entrapped orbital adipofascial tissue and medial rectus muscle. The fracture was repaired using a transcaruncular approach.

Fig. 3. Full extraocular motility and full opening of the eyes was regained without any vasovagal symptoms. Images were taken two months following the surgical treatment.

In 1998, Jordan et al. [1] first described a white-eyed blowout fracture with a restriction of the upward gaze caused by incarceration of the inferior rectus muscle in children. It was reported that this fracture presented without signs of soft tissue injury, including edema, ecchymosis, or subconjuctival hemorrhage (known as the 'black-eye signs'). Therefore, the diagnosis of white-eyed blowout fractures can be initially missed owing to the benign presentation. The importance of early recognition and treatment has been previously emphasized. Ischemic muscle necrosis caused by entrapment is thought to lead to muscle fibrosis, retraction of ocular motion and persistent diplopia. They also reported that patients treated within 4 days of injury showed a complete resolution of symptoms and had no permanent restriction of ocular motion [1,2]. Although there is less clinical data with medial wall fractures, the patient presenting diplopia with evidence of medial rectus entrapment should also need early surgical treatment.

The majority of pediatric patients with white-eyed blow out fractures present with an increase in light-headedness, nausea and vomiting, associated with eyeball movement. These symptoms are related to the increase in vagal tone arising from the oculocardiac reflex. The oculocardiac reflex is mediated by nerve connections between the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal cranial nerve and the vagus nerve of the parasympathetic nervous system via ciliary ganglion. In some cases, this can cause complications, including bradycardia and heart block [3]. And these symptoms such as dizziness, vomiting are mimicking head injury and causing discomfort of eye opening, therefore, definitive ophthalmic exams such as diplopia test or forced duction test might be disturbed. Besides, the exams in the condition of the increased vasovagal tone are more intolerable to children than adults. At this time, CT imaging is a very useful technique for identifying fracture. In cases where the fracture is too small to be detected easily in CT imaging, the rounded extraocular muscle adjacent to the fracture site can be used as another hint for fracture, even there is no signs of soft tissue injury [4]. The association of an oculocardiac reflex with orbital fracture is not common but prompt identification is important, and the immediate repair should be suggested for better prognosis [3].

The medial wall fracture is usually presented combined with a floor fracture rather than isolated form and this case is particular due to the pediatric patient with the predominance of oculocardiac reflex symptoms, which were initially mistaken as intracranial injury. The correct diagnosis could be made following a detailed medical history, physical examination and CT scan. Since the bone composition in children is more elastic and thicker than in adults, applied forces can result in a small sized fracture such as a greenstick or trapdoor fracture. For this reason, the role of orbital reconstruction has not been emphasized [5]. The patient reported here underwent only surgical release without any implantation or graft for orbit wall reconstruction.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jordan DR, Allen LH, White J, et al. Intervention within days for some orbital floor fractures: the white-eyed blowout. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:379–390. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tse R, Allen L, Matic D. The white-eyed medial blowout fracture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:277–286. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000237032.59094.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sires BS, Stanley RB, Jr, Levine LM. Oculocardiac reflex caused by orbital floor trapdoor fracture: an indication for urgent repair. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:955–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiasson G, Matic DB. Muscle shape as a predictor of traumatic enophthalmos. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2010;3:125–130. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yenice O, Ogut MS, Onal S, et al. Conservative treatment of isolated medial orbital wall fractures. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2006;37:497–501. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20061101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]