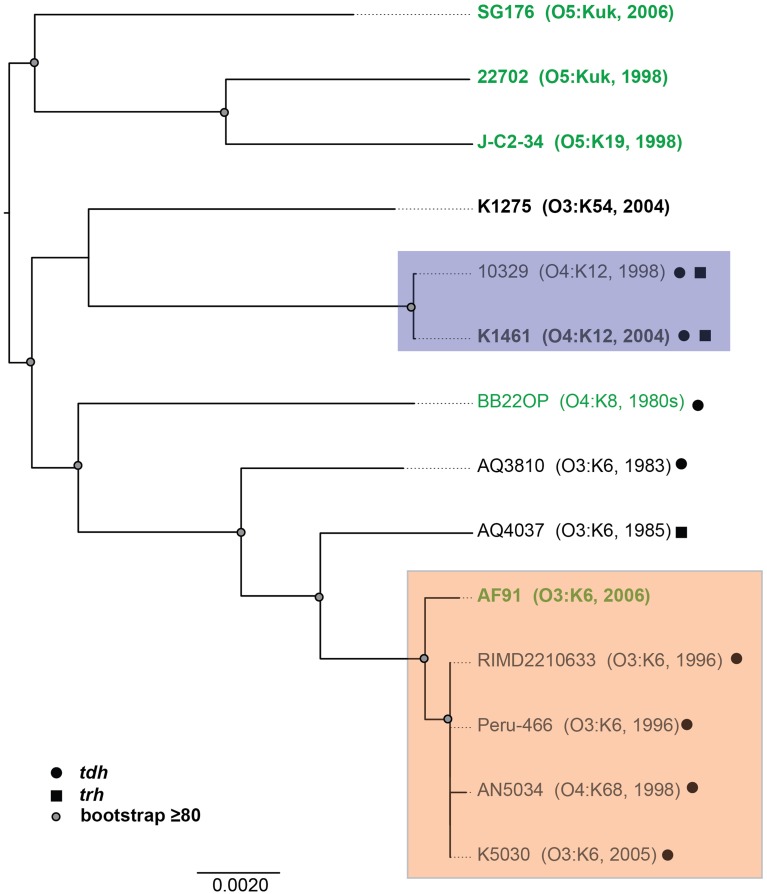

Figure 2.

Phylogenomic analysis of the six V. parahaemolyticus clinical and environmental isolates sequenced in this study (indicated in bold) compared to eight V. parahaemolyticus genomes that have been previously sequenced (Makino et al., 2003; Boyd et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2011; Gonzalez-Escalona et al., 2011; Jensen et al., 2013) and are available in the public domain. The genomes were aligned using Mugsy (Angiuoli and Salzberg, 2011), and an approximately 4.0 Mb region of each genome that aligned was concatenated to generate a single sequence for each isolate as previously described (Sahl et al., 2011). A maximum-likelihood phylogeny with 100 bootstrap replicates was constructed using RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006) and visualized using FigTree v1.3.1 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Bootstrap values ≥80 are indicated by a circle. The genomes of V. parahaemolyticus isolates from environmental sources are indicated in green, while the isolates from clinical sources are indicated in black. The post-1995 O3:K6 isolates are identified by the orange box, and the O4:K12 isolates are indicated by a purple box. The presence of the virulence-associated thermostable direct hemolysins, tdh and trh, in each of the genomes is indicated by symbols.