Significance

This paper describes the development of a computationally designed enzyme that is the cornerstone of a novel metabolic pathway. This enzyme, formolase, performs a carboligation reaction, directly fixing one-carbon units into three-carbon units that feed into central metabolism. By combining formolase with several naturally occurring enzymes, we created a new carbon fixation pathway, the formolase pathway, which assimilates one-carbon units via formate. Unlike native carbon fixation pathways, this pathway is linear, not oxygen sensitive, and consists of a small number of thermodynamically favorable steps. We demonstrate in vitro pathway function as a proof of principle of how protein design in a pathway context can lead to new efficient metabolic pathways.

Keywords: computational protein design, pathway engineering, carbon fixation

Abstract

We describe a computationally designed enzyme, formolase (FLS), which catalyzes the carboligation of three one-carbon formaldehyde molecules into one three-carbon dihydroxyacetone molecule. The existence of FLS enables the design of a new carbon fixation pathway, the formolase pathway, consisting of a small number of thermodynamically favorable chemical transformations that convert formate into a three-carbon sugar in central metabolism. The formolase pathway is predicted to use carbon more efficiently and with less backward flux than any naturally occurring one-carbon assimilation pathway. When supplemented with enzymes carrying out the other steps in the pathway, FLS converts formate into dihydroxyacetone phosphate and other central metabolites in vitro. These results demonstrate how modern protein engineering and design tools can facilitate the construction of a completely new biosynthetic pathway.

Novel strategies are needed to address current challenges in energy storage and carbon sequestration. One approach is to engineer biological systems to convert one-carbon compounds into multicarbon molecules such as fuels and other high value chemicals. Many synthetic pathways to produce value-added chemicals from common feedstocks, such as glucose, have been constructed in organisms that lack one-carbon anabolic pathways, such as Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1–3); however, despite considerable effort, it has been difficult to introduce heterologous one-carbon fixing pathways into these organisms (4). Likely problems include the inherent complexity, environmental sensitivity, inefficiency, or unfavorable chemical driving force of naturally occurring one-carbon metabolic pathways (5).

An optimal pathway for one-carbon utilization in common synthetic biology platforms would be (i) composed of a minimal number of enzymes, (ii) linear and disconnected from other metabolic pathways, (iii) thermodynamically favorable with a significant driving force at most or all steps, and (iv) capable of functioning in a robust manner under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (5). A pathway with these properties could enable the assimilation of one-carbon molecules as the sole carbon source for the production of fuels and chemicals. Although no such pathway is known in nature, the established electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate under ambient temperatures and pressures in neutral aqueous solutions provides an attractive starting point for a one-carbon fixation pathway (5–8).

We describe the computational design of an enzyme that catalyzes the carboligation of three one-carbon molecules into a single three-carbon molecule. This enzyme enables the construction of a new pathway, the formolase pathway, in which formate is converted into the central metabolite dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP; Fig. 1). The use of computational protein design to reengineer catalytic activities opens up the pathway design space beyond that available based on existing enzymes.

Fig. 1.

Overview of formolase pathway reactions. (A) Benzaldehyde lyase couples two benzaldehydes into benzoin through an acyloin addition reaction. (B) Acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) catalyzes the ATP-dependent conversion of acetate into acyl-CoA. (C) Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ACDH) catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde. (D) Conversion of formate to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by the formolase pathway. To generate reducing equivalents in the cell, formate is oxidized by formate dehydrogenase (FDH) to produce CO2 and NADH (stage 1). To use formate as a carbon source, activation (stage 2) and carbon-carbon coupling (stage 3) to form dihydroxyacetone (DHA) are carried out by the enzymes ACS, ACDH, and formolase (FLS). DHA is phosphorylated to DHAP, a glycotic intermediate by a dihydroxyacetone kinase (DHAK) (stage 4). The novel enzyme functions identified here are underlined.

Results

Identification of a Starting Point for a Carboligation Catalyst.

The direct coupling of formate into a multicarbon molecule has no precedent in the biochemical literature, but the coupling of formaldehyde (FALD) into dihydroxyacetone (DHA; the formose reaction) has been well characterized in organic synthesis (9). No enzyme, however, has been previously reported to catalyze this reaction (9). Therefore, initial efforts focused on designing such an enzyme. In considering how to catalyze this reaction, we were guided by the observation that thiazolium salts catalyze the formose reaction. As thiazolium is the core functional moiety of thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP)-dependent enzymes, we explored this class of enzymes for those potentially capable of performing the formose reaction. We identified the enzyme benzaldehyde lyase (BAL) as a promising starting point (Figs. 1A and 2A). Although BAL has not previously been demonstrated to catalyze the formose reaction, it catalyzes the related coupling of two benzaldehyde (BzALD) molecules into benzoin. The primary difference between these reactions is that the conversion of FALD to DHA requires two rounds of carbon-carbon coupling steps, whereas BzALD to benzoin requires only one. We hypothesized that, although multiple carbon-carbon couplings with BzALD are not feasible due to the single aldehyde hydrogen on BzALD, FALD has two aldehyde hydrogens and could potentially undergo two rounds of carbon-carbon coupling (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). To investigate possible formose activity, the gene for BAL from Pseudomonas fluorescens biovar I was synthesized, and the corresponding enzyme was expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods (10).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of design model and crystal structure. (A) Native BAL (PDB ID code 2AG0) with TPP and a docked model of benzoin in the active site. The residues that were mutated in the designed formose enzyme (FLS) are highlighted in brown. (B) Model of FLS active site with the four active site mutations (brown) around the DHA bound intermediate (purple). (C) Overlay of the Des1 crystal structure (blue) and the FLS model (green, with mutated residues brown) with the docked DHA product (purple). The four active site mutations (BAL vs. Des1) are shown in sticks, conserved amino acids in lines. Figure made with PyMol (38).

BAL formose activity was assessed using two independent assays. First, incubation of BAL with 13C-FALD led to new peaks in the NMR spectra. The chemical shifts and J-coupling correspond to the expected two carbon [glycolaldehyde (GALD), first carbon-carbon coupling of two FALDs] and the three-carbon (DHA) 13C products of the formose reaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Second, the catalytic efficiency of BAL for the formose reaction was determined using a coupled enzyme assay in which DHA or GALD is reduced by the NADH-dependent enzyme glycerol dehydrogenase. Enhanced NADH oxidation rates were detected only in the presence of all of the components, and activity was dependent on both the concentration of FALD and BAL. The kcat/KM of BAL for the formose reaction was estimated from linear fits to substrate vs. velocity profiles (no saturation was observed at up to 20 mM FALD) and found to be ∼5.0 × 10−2 M−1⋅s−1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), 36,000-fold lower than the kcat/KM for BzALD (1.8 × 103 M−1⋅s−1; Table 1). The elucidation of the mechanism and full product profile of the formose reaction will require further quantitative analysis.

Table 1.

Kinetic constants of BAL and FLS

| Enzyme | Catalytic efficiency, M−1⋅s−1 | |

| Benzoin reaction | Formose reaction | |

| BAL | 1.8 × 103 ± 1.1 × 102 | 5.0 × 10−2 ± 4.0 × 10−3 |

| FLS | n.d.a. | 4.7 ± 0.1 |

The catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM in units of M−1⋅s−1) for both FLS and BAL for both the benzoin and formose reaction obtained from linear fits to substrate vs. velocity profiles, as described in Materials and Methods. All fits had at least four independently measured rates with an R2 > 0.9 and are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. n.d.a., no detectable activity.

Computational Design of a Formose Catalyst.

Next, computational protein design was used to redesign the BzALD binding pocket of BAL to increase specificity and activity for FALD and the formose reaction. FALD molecules—much smaller than the native ligand BzALD (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3)—were modeled into the BAL crystal structure, and RosettaDesign and Foldit calculations were used to fill in the considerable empty space to increase binding affinity for FALD (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Four iterations of computational design and experimental evaluation ranging from 1 to 42 designs per cycle, with 121 designs in total evaluated, led to a variant we call Des1 with 26-fold higher activity and four amino acid substitutions: A28I, A394G, G419N, and A480W (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In this design, a new hydrogen bond is predicted to form between the DHA transition state and G419N. In addition, packing interactions are predicted to occur with A480W and A28I on the carbon backbone of DHA.

To determine if these mutations had a significant effect on the structure, we crystalized and solved the structure of Des1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 and Table S2). The RMSD between Des1 and BAL was 0.6 Å, and there were no significant changes in backbone structure throughout the active site (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Comparison of the three mutated nonglycine amino acids showed that the computational modeling was accurate, as all three displayed the same rotameric conformation as in the original design.

One additional mutation was then identified through a round of computationally guided site-directed mutagenesis (L90T; SI Appendix, Fig. S4), and two mutations were found through error-prone PCR (W89R and R188H; SI Appendix, Fig. S4) that together further increased activity of Des1 fourfold. The mutation L90T, which reduces the size of the corresponding side chain at that position is near one of the original four computationally engineered mutations, G419N, and may be important for fine-tuning binding interactions. The two mutations from error-prone PCR are at the protein–protein interface, and their role is unclear. We crystalized and solved the structure of this seven-site mutant [A28I, W89R, L90T, R188H, A394G, G419N, and A480W, termed formolase (FLS); SI Appendix, Fig. S4 and Table S2]. The identity and position of the additional mutated side chains was clear in the electron density, and the overall conformation of the protein backbone and active site was similar to the Des1 construct (RMSD of ∼0.4 Å across all main chain atoms).

FLS has a catalytic efficiency for the formose reaction of 4.7 M−1⋅s−1, which is roughly a 100-fold increase in formose activity from the original BAL enzyme (Table 1). Furthermore, FLS exhibited no detectable activity for the benzoin reaction at concentrations up to 10 µM enzyme and 20 mM BzALD over 1 h. Based on the detection limit of the assay, this is a >100,000-fold decrease in benzoin activity, resulting in a specificity switch between BAL and FLS of greater than 10 million-fold.

Reduction of Formate into FALD.

An active FLS creates the opportunity to design a pathway to convert formate to DHAP (Fig. 1). The first conversion, the direct reduction of formate to FALD, has a very low redox potential (Eo′ ∼ −600 mV at pH 7 and ionic strength of 0.2 M, considerably lower than any cellular electron carrier). Hence, the direct reduction of formate using NADH is an extremely unfavorable reaction. To enable the overall desired conversion of formate to FALD, we sought to activate formate to formyl-CoA, reducing the thermodynamic barrier for the reduction to FALD by NADH (Fig. 1D). No enzymes are known to carry out this reaction, but acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) carries out a similar reaction with a related compound, acetate (Fig. 1B), and the differences between formate and acetate should not significantly affect the reaction chemistry. Formyl-CoA is not produced or hydrolyzed in any known primary metabolic pathway of E. coli (11). In addition, under standard E. coli cytoplasmic conditions, the ATP-dependent formation of formyl-CoA can have a ΔrG′° as low as −4 kcal/mol (12, 13). Because E. coli has an ACS enzyme, we cloned the gene from the genomic DNA, and the corresponding enzyme (ecACS) was expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods (14, 15). EcACS-dependent 13C-labeled formyl-CoA production was assayed using a previously established liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method and adjusting the expected masses to correspond to formyl-CoA as described in Materials and Methods. A clear signal for the expected parent and product ion of 13C-labeled formyl-CoA was observed in the presence of 13C-formate, ATP, and ecACS (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), but not in the absence of any substrate.

The second step of the pathway is the reduction of formyl-CoA to FALD. There is no enzyme established to catalyze this reaction, but there are enzymes known to catalyze the reversible reduction of acetyl-CoA into acetaldehyde. We tested acylating acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ACDH; Fig. 1C) for its ability to produce formyl-CoA from FALD, CoA, and NAD. Little activity was observed with the E. coli ACDH enzyme (SI Appendix, Table S1), so we used the BRENDA database to identify a set of five homologous ACDH enzymes (SI Appendix, Table S1) (16–18). Genes encoding the native sequence for each enzyme were synthesized, and the proteins produced and purified as described in Materials and Methods. The proteins were assayed for NADH production using HSCoA and either acetaldehyde or FALD as substrates (SI Appendix, Table S1). The most active of the enzymes, a putative acylating aldehyde dehydrogenase from Listeria monocytogenes, lmACDH, had a catalytic efficiency with FALD of 5.3 M−1⋅s−1, ∼100-fold greater for FALD and 400-fold greater for acetaldehyde than ecACDH.

We next characterized the conversion of formate to FALD by ecACS and lmACDH acting in tandem (Fig. 1D, stage 2). The oxidation of NADH was monitored in the presence of formate, CoA, ATP, NADH, ecACS, and lmACDH. Significant NADH oxidation was observed only in the presence of both enzymes (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Thus, consistent with the independent assays on each individual enzyme, the two enzymes together are capable of reducing formate to FALD. The ACS activity appears to be limiting as there was a significant reduction in rate on decreasing ecACS 10-fold, whereas a 10-fold reduction of the lmACDH concentration had little effect.

The Formolase Pathway.

On establishing the individual steps for the conversion of formate into DHA, we constructed the entire pathway, which derives both the carbon and the NADH from formate. The formolase pathway has four key stages (Fig. 1D): (i) generation of reducing equivalents by FDH, (ii) carbon activation and reduction by ecACS and lmACDH, (iii) carbon–carbon bond formation by FLS, and (iv) assimilation into a central metabolite by phosphorylation of DHA using DHA kinase (DHAK). To explore the ability for this pathway to function in vitro, we incubated 13C-formate with purified FDH, ecACS, lmACDH, FLS, and DHAK at room temperature and followed the appearance of 13C-labeled DHAP using LC-MS/MS. In the presence of all of the enzymes, substrates, and cofactors, 13C-DHAP was clearly observed and increased linearly over time (Fig. 3A). In the absence of 13C-formate, FDH, ecACS, lmACDH, or FLS, no 13C-DHAP was formed (Fig. 3B). The replacement of FLS with an equivalent protein concentration of BAL eliminates detectable production of 13C-DHAP. Thus, the functionality of the entire pathway is dependent on the computationally designed molecular interactions in the FLS enzyme.

Fig. 3.

Formolase pathway conversion of formate into dihydroxyacetone-phosphate by purified enzymes. (A) Production of 13C-DHAP from 13C-Formate by the combination of purified ecACS, lmACDH, FLS, FDH, and DHAK. Production of DHAP absolutely requires FLS. (B) (Upper) Dependence of 13C-DHAP production on reaction components. (Lower) The SDS/PAGE gel illustrates the protein levels for each component; the concentration of FDH is too low to be evident on the gel. Each rate is based on a linear fit to five independent measurements. Error bars represent SE.

To probe for bottlenecks in the pathway, we independently titrated the concentration of ecACS, lmACDH, and FLS and measured 13C-DHAP production rates (Fig. 3B). Decreasing FLS or ecACS by 10-fold resulted in 6-fold and 4-fold decreases in the rate of DHAP production, respectively, indicating that both ecACS and FLS are partially rate limiting. A 10-fold decrease in lmACDH concentration did not decrease product formation, consistent with the previous identification of ecACS as the rate limiting of the two enzymes. Overall, these results are consistent with our designed pathway and identify FLS and ecACS as bottlenecks to target for future enzyme engineering efforts.

After ascertaining pathway activity with purified enzymes, we expressed the pathway in a single strain to determine feasibility in a cellular context. We tested clarified cellular lysates from ALA2.1, a fdoG MG1655-derived E. coli strain, expressing DHAK from S. cerevisiae (yDHAK), ecACS, lmACDH, and FLS for conversion of 13C-formate into cellular intermediates. The lysate was incubated with appropriate cofactors and commercial FDH, and incorporation of 13C-formate into pathway and central metabolic intermediates was measured via LC-MS/MS. Clear increases in the 13C-labeled metabolite DHAP and downstream glycolytic intermediates, 2/3-phosphoglycerate (2/3-PG; Fig. 4), were detected only in the presence of labeled formate with the pathway present. Controls lacking ecACS, lmACDH, and FLS did not yield increased 13C-labeled DHAP in the presence of 13C-formate regardless of formate presence. More than 40% labeling of the DHAP and 2/3-PG pools was achieved after 24 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The ALA2.1 strain containing the genes for ecACS, lmACDH, FLS, yDHAK, formate dehydrogenase from Candida methylitica (cmFDH), and formate transporters (FocA or FocB) (19, 20) was tested for formate-dependent growth on agar plates and in liquid cultures, but none was detected.

Fig. 4.

Conversion of formate into the central metabolites DHAP and 2/3-PG by cell lysates. Protein-normalized concentrations of 13C-DHAP (DHAP M+3), and 13C-2/3-PG (2/3-PG M+3) in clarified cell lysates with the pathway genes for ecACS, lmACDH, FLS, and yDHAK (pTrcCO2-3, pSB3K3 yDHAK), or in the absence of the key formate assimilation enzymes with only yDHAK (pTrcHis2, pSB3K3 yDHAK), after incubation with 13C-formate for 24 h. Commercial FDH was added to balance the net NADH oxidation rate of the test extracts in a 1:1 ratio as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent the SE of measurements for three biological replicates.

Discussion

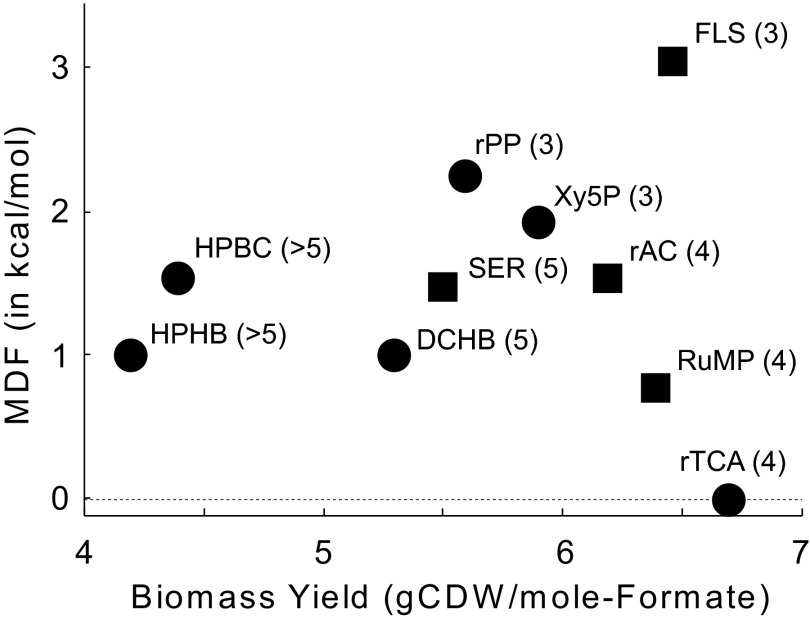

The unique enzyme functions identified and designed here provide a potential route for the biocatalytic conversion of one-carbon molecules into central metabolites. The formolase pathway compares favorably in many respects with the nine known naturally occurring pathways for one-carbon utilization starting from formate or carbon dioxide (Fig. 5) (6, 21). It requires only five steps to convert the carbon source into a central metabolite, fewer than all naturally occurring pathways. It is also predicted to support a biomass yield higher than any other pathway [6.5 g cellular dry weight (gCDW)/mol formate] except the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle (6.7 gCDW/mol formate) (6). However, the rTCA cycle is thermodynamically unfavorable in the cytosolic conditions of E. coli and uses oxygen-sensitive enzymes, whereas the formolase pathway is thermodynamically favorable and can function under full aerobic conditions (6, 21). In addition to highly efficient carbon utilization, the formolase pathway has a high chemical driving force (>3 kcal/mol) throughout its entire reaction sequence, a driving force considerably higher than in any other pathway (Fig. 5) (6). Such a high chemical driving force ensures that the pathway can effectively proceed without backward flux.

Fig. 5.

Thermodynamics and carbon utilization efficiencies. Biomass yield, in gram cellular dry weight (gCDW) per mole of formate consumed, was calculated using flux balance analysis and the core metabolic model of E. coli supplemented with pathway enzymes and without considering ATP maintenance (6). The MDF is the lowest value of −ΔrG′ in the pathway [for the reaction(s) with the smallest chemical driving force force] (37). Squares correspond to pathways that can directly assimilate formate, whereas circles mark carbon fixation pathways that can indirectly assimilate formate following oxidation. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of foreign enzymes that need to be expressed in E. coli to establish an active pathway. Pathway abbreviations are as follows: DCHB, dicarboxylate-4-hydroxypropionate cycle; FLS, formolase pathway; HPBC, 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle; HPHB, 3-hydroxypropionate-4-hydroxybutyrate cycle; rAC, reductive acetyl-CoA pathway; rPP, reductive pentose phosphate cycle/Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle; rTCA, reductive TCA cycle; RuMP, ribulose 4-phosphate cycle; SER, serine cycle; Xy5P, xylulose 5-phosphate cycle/dihydroxyacetone cycle).

This report provides a demonstration of FLS activity and a proof-of-principle demonstration for the potential of a formolase pathway. At this point, the activities of the enzymes involved in the pathway are low, likely contributing to the lack of detectable growth on formate. In addition, the pathway involves on the highly reactive FALD. There are clear routes forward to address both issues. First, it should be possible to significantly increase enzyme activities by a combination of design and selection considering that no optimization was carried out with either ecACS or lmACDH. Second, it should be possible to repurpose microbial microcompartments such as the carboxysome, which have evolved to harbor pathways with reactive one-to-two-carbon components, now that the targeting signals for directing enzymes to these compartments are becoming better understood (22–24). Once in vivo metabolic activity of the pathway is established, the formolase pathway could be further extended to use CO2 as a sole carbon and energy source through the electrochemical reduction of CO2 into formate (25).

Almost all synthetic biology efforts to date have recombined naturally occurring components. For the full promise of this exciting field to be realized, it will be necessary to broaden the palette of components to include new designed proteins specifically built for the problem at hand—naturally occurring proteins are optimized for the challenges faced during biological evolution and not the current challenges we face today. The coupling of computational design—exemplified by the 100-fold increase in FLS activity and the 10 million-fold switch in specificity—with metabolic engineering described here represents a powerful approach to addressing 21st century challenges.

Materials and Methods

For additional information, please see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Cloning.

Codon-optimized versions of the genes for BAL, FLS, lmACDH, cmFDH, and yDHAK were obtained from Genescript cloned into pET29b+ vectors (Novagen). ecACDH and ecACS were amplified from genomic material and cloned into the pET29b+ expression vector between NcoI and BamHI.

pTrcCO2-3 was designed for simultaneous expression of the three critical enzymes in the formolase pathway. EcACS, Des1, and lmACDH were placed under control of a single isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible trc promoter in the expression vector pTrcHis2C (Invitrogen) by Gibson cloning. An alternate system of expressing ecACS, ecACDH, yDHAK, and Des1 was also constructed (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

yDHAK and cmFDH were combined in constructs along with formate transporter, focA, or putative formate transporter, focB. Genes for yDHAK and cmFDH were amplified from pET29b+ yDHAK and pET29b+ cmFDH. focA and focB were amplified from E. coli BL21 genomic DNA. These PCR products were cloned via the Biobrick system into vector backbone pSB3K3 with a high constitutive expression cassette (BBa_K314100) or a low constitutive expression cassette (BBa_K314101) in various combinations (26–28). pSB3K3 J23100 DHAK and a set of four constructs, pSB4C5 J23100/114 cmFDH J23114 yDHAK J23114 FocA/B (pSB4C5 FDF3-6), were created.

Enzyme Engineering.

Computational design.

The reaction intermediate for DHA was built into the crystal structure of BAL (2AG0) based on the geometric orientation observed for the related reaction intermediate observed in 3FSJ (a closely related enzyme, benzylformate decarboxylase, with a mechanism based covalent inhibitor bound to TPP) using ChemDraw 3D (29, 30). The 3D coordinates are provided in SI Appendix, Table S3. This model was used as input for RosettaDesign and Foldit-based optimization using previously described methods (31, 32). Briefly, Rosetta was used to evaluate the overall energy of the system as well as the interface energy between the protein and intermediate. Either Monte Carlo combinatorial optimization of amino acid identity and conformation was carried out using RosettaDesign, or substitutions were manually introduced using Foldit. During design, neighboring side chains were allowed to change conformations and the overall protein backbone and the protein-ligand rigid body interface were subjected to gradient based minimization. Selected sequences were experimentally characterized as described in the text. At each round, the model with the lowest overall system energy was selected for analysis of the interactions with the reaction intermediate, and as starting points for the RosettaDesign and Foldit calculations (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods, Design Cycle Summary Des1). Mutants were constructed using Kunkel mutagenesis (33), and corresponding proteins were produced, purified, and assayed as described below.

Error-prone PCR library.

The Agilent Genemorph II Kit was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to introduce on average two mutations per kilobase into the Des1 gene. After amplification, the mutant library was restriction cloned into pET29b+ using NdeI and XhoI sites and electroporated into E. coli DH5α. Mutation frequency was verified by sequencing 24 isolated clones. A total of 528 colonies were screened using the protein production, purification, and assays in a 96-well microtiter plate format. The top seven mutations were combined combinatorially using Kunkel mutagenesis (33); from which a second set of 528 random colonies was screened. In this screened set, mutants with up to three simultaneous mutations were observed. The enzyme with the highest activity was further optimized through computationally guided site-directed mutagenesis.

Computationally guided Kunkel library construction.

Using the Rosetta Molecular Modeling Suite, every point mutation within 15 Å of the Des1 enzyme active site was systematically mutated into each of the twenty amino acids. After generating the ∼2,000 point mutants, all residues within 20 Å of the active site were repacked and minimized in the context of the modeled FLS transition state. Mutants with Rosetta energy greater than that of the unmutated protein were discarded (∼50% of all mutants). The remaining substitutions were sorted by energy, and a total of 380 (up to five at any position) were selected for construction and experimental characterization. Each point mutation was generated using standard Kunkel mutagenesis techniques as previously reported (33).

Structure determination.

Structures of Des1 and FLS were solved with X-ray crystallography. The methods and the final data and refinement statistics are reported in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods and Table S2, respectively. X-ray crystallographic coordinate data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under ID codes 4QPZ (Des1) and 4QQ8 (FLS).

Protein Purification.

Constructs, pET29b+ versions, were transformed into chemical competent E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). A single colony was picked and cultured overnight in 3 mL terrific broth (TB) medium at 37 °C. This culture was decanted into 0.5 L of TB medium and incubated at 37 °C until midlog phase. Expression of the gene of interest was induced with 1 mM IPTG. After 30 h, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, pH 7.5, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME), 1 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM TPP, and 10 mM imidazole and lysed by sonication in the presence of lysozyme. Lysates were cleared of cell debris by centrifugation and purified using Talon resin in a gravity-fed column (Clontech). The resin was washed three times with 20 mL PBS, pH 7.5, 1 mM βME, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM TPP, and 10 mM imidazole. Elution was done with 15 mL PBS, pH 7.5, 1 mM βME, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM TPP, and 200 mM imidazole. Eluate was concentrated to ∼1 mL before dialysis against PBS, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM βME, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.2 mM TPP.

Enzyme Assays.

Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were sourced from Sigma.

Kinetic constant determination.

Kinetic constants for BAL and FLS were measured over a 1-h period in 100 mM KPO4 buffer, pH 8.0, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM TPP. Enzyme concentrations ranged from 1 to 40 µM, and substrate (either FALD or BzALD) concentrations ranged from 20 to 1.3 mM. FALD to DHA was measured using the coupled enzyme assay described later. Benzoin formation was measured by quenching the reaction in acetonitrile every 10 min and measuring benzoin through liquid chromatography. Kinetic constants for each enzyme using either FALD or benzoin as a substrate were calculated using nonlinear regression fitting of rate of product production as a function of substrate concentration using the Michaelis–Menten equation or to a linear equation if no slope was apparent.

NMR analysis.

Experiments were done with the University of Washington Chemistry Facilities Staff. The sample [20 µM BAL, 20 mM 13C-FALD (Cambridge Isotope Labs), 0.1 mM TPP, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM KPO4, pH 8.0] was incubated for 3 h after which the NMR spectra of each sample using standard methods for 13C detection was measured. Samples with and without enzyme and or FALD present were carried out. Samples of 0.5 M 12C-GALD or DHA under equivalent conditions, but without enzyme or FALD, were used to determine the chemical shifts of the expected products. In this case, natural abundance 13C was measured.

ACS formyl-CoA measurement.

EcACS, 40 µM, was added to an assay mixture with 63 mM 13C-formate (Cambridge Isotope Labs), 12.5 mM ATP, 2.5 mM HSCoA, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM DTT, and 150 mM KPO4, pH 8.0, and incubated for 24 h at room temperature. LC-MS/MS detection of formyl-CoA was performed as in Buescher et al., adapting the given parameters for acetyl-CoA to fit formyl-CoA (34).

ACDH assay.

For each ACDH candidate, a mixture of 1.8 µM protein, 10 mM aldehyde, 0.5 mM NAD, 0.5 mM HSCoA, 0.5 mM DTT, 10 µM ZnSO4, 1× PBS, and 3 mM imidizole was monitored for NADH formation at 340 nm.

Coupled ACS-ACDH enzyme assay.

Purified proteins, ecACS and ACDH, or lysate containing them, were combined with an assay mix of 1 mM NADH, 0.2 mM HSCoA, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM TPP, 0.1 mg/mL glycerokinase, 250 mM KPO4, pH 8.0, and 50 mM formate. NADH concentrations were monitored as in the ACDH assay.

Coupled FLS enzyme assay.

Lysate-containing or purified FLS was combined with an assay mix of 100 mM NaPO4 buffer, pH 8.0, 2 mM MgSO4, 50 µg/mL glycerol dehydrogenase, 0.8 mM NADH, 134 mM FALD, and 0.1 mM TPP. NADH concentrations were monitored as in the ACDH assay.

Talon bead-based high-throughput screening.

Protein expression as described above was altered for high throughput in plate format. The cultures were spun down and lysed chemically with BugBuster (Novagen). Debris was removed by centrifugation. Lysates were applied to a filter plate containing TALON beads. Three rounds of washing were followed by elution at high imidazole. Protein content of the flow through was measured using A280, and the coupled FLS enzyme assay was used to detect FLS activity.

Lysate-based robotic high-throughput screening.

The computationally directed FLS Kunkel library was assessed with robotic high-throughput screening. Inoculated with single colonies, 1,860 overnight cultures, an approximate fivefold oversampling of the library size, were used to start TB expression cultures in deep well plates. At midlog phase, 0.5 mM IPTG was added to induce expression overnight at 18 °C. Cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C until screening. Cells were lysed chemically and centrifuged to remove debris. A plate format coupled FLS assay was performed on the supernatants. Unique variants were then purified further for detailed kinetic analysis, as described above.

In vitro crude cell lysate assay.

Chemically competent E. coli, ALA2.1, described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods was transformed with appropriate constructs. Cell pellets were created as in the robotic high-throughput screening, except expression occurs for 24 h. Thawed pellets were resuspended in 3 mL protein buffer (10 mM KPO4, pH 8.0, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM TPP, and 0.025 mM DTT). Cell lysates were prepared by two passages through a french press (SIM-Aminco; Spectronic Instruments) with minicell (1,000 psig), followed by ultracentrifugation (Beckman) at 4 °C and 45,000 rpm (Beckman MLS 50 rotor) for 1 h and desalting with PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare).

NADH oxidation rates of the resulting clarified cell lysates (CCLs) were measured using a variant of the coupled ACS-ACDH activity assay with 150 mM KPO4, 0.2 mM TPP, 2 mM MgSO4, 11 mM ATP, 0.5 mM NADH, 0.2 mM HSCoA, 50 mM 13C-sodium formate, and 0.1 mM DTT. NAD reduction rates by FDH from Candida boidinii (10 mg/mL) were measured in the same assay mixture with NAD replacing NADH and without HSCoA. The FDH solution to CCL volumetric ratio was determined by balancing the average NADH oxidation rate of the full pathway CCLs to that of the FDH in a 1:1 ratio. This ratio was applied to all CCLs to give CCL + FDH 1:1 mixtures.

The assay mixture [as above with 1 mM NAD instead of NADH and 50% (vol/vol) CCL + FDH 1:1 preparations] was vortexed and then incubated at room temperature. Every 8 h, additional ATP, 13C-formate, and DTT were added to boost concentrations by 2.5 mM, 10 mM, and 10 µM, respectively. At each time point, 150 µL of the reaction was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The fast centrifugation method from Kleijn et al. was adapted for use with cell extracts (35). LC-MS/MS analysis was performed as in Buescher et al. with minor adjustments (34). Internal standard curves made with 12C compounds were used for quantification. Isotope correction for natural abundance was done using the Isocor software (36).

Computation of Biomass Yield and Max–Min Driving Force.

Biomass yield, in gram cellular dry weight per mole of formate consumed, was calculated using flux balance analysis and the core metabolic model of E. coli supplemented with pathway enzymes and without considering ATP maintenance (6). All energy-conserving electron bifurcation reactions were neglected in this analysis. The max–min driving force (MDF) is the lowest value of −ΔrG′ in the pathway [i.e., the reaction(s) with the smallest chemical driving force], after optimizing reactant concentrations within a physiological range (1 µM to 10 mM for noncofactors) as described in the SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods and Bar-Even et al. (37). The cytoplasmic concentration of formate was assumed to be 10 mM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Olga Khersonsky, Christy Tinberg, Matthew Harger, Janet Matsen, Nick Chavkin, and Curt Fischer, and Jason Kelley of Ginkgo Bioworks for assistance. This work was supported by Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy Project DE-AR0000091; the Joint BioEnergy Institute, which is funded by the Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the US Department of Energy (Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231); National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM498578 (to B.W.S. and B.L.S.); National Science Foundation (NSF) Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Grant Graduate Education (DGE)-0654252 (to A.L.S.); NSF Graduate Research Fellowships Program Grants DGE 1106400 (to S.P.) and DGE 0718124 (to J.B.); and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4QPZ (Des1) and 4QQ8 (FLS)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1500545112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Keasling JD. Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science. 2010;330(6009):1355–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1193990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolston BM, Edgar S, Stephanopoulos G. Metabolic engineering: Past and future. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2013;4:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061312-103312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gronenberg LS, Marcheschi RJ, Liao JC. Next generation biofuel engineering in prokaryotes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17(3):462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller JEN, et al. Engineering Escherichia coli for methanol conversion. Metabol Eng. 2015;28:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar-Even A, Noor E, Lewis NE, Milo R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(19):8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Even A, Noor E, Flamholz A, Milo R. Design and analysis of metabolic pathways supporting formatotrophic growth for electricity-dependent cultivation of microbes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(8-9):1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Innocent B, et al. Electro-reduction of carbon dioxide to formate on lead electrode in aqueous medium. J Appl Electrochem. 2008;39(2):227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal AS, Zhai Y, Hill D, Sridhar N. The electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formate/formic acid: Engineering and economic feasibility. ChemSusChem. 2011;4(9):1301–1310. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201100220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslow R. On the mechanism of the formose reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959;1(21):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.González B, Vicuña R. Benzaldehyde lyase, a novel thiamine PPi-requiring enzyme, from Pseudomonas fluorescens biovar I. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(5):2401–2405. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2401-2405.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keseler IM, et al. Ecocyc: Fusing model organism databases with systems biology. Nucl Acids Res. 2013;41:D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett BD, et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(8):593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flamholz A, Noor E, Bar-Even A, Milo R. eQuilibrator—the biochemical thermodynamics calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D770–D775. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase (AMP forming) Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(16):2020–2030. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3448-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown TD, Jones-Mortimer MC, Kornberg HL. The enzymic interconversion of acetate and acetyl-coenzyme A in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;102(2):327–336. doi: 10.1099/00221287-102-2-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark DP, Cronan JE. 1980. Acetaldehyde coenzyme A dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 144(1):179–184.

- 17.Shone CC, Fromm HJ. Steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics of coenzyme A linked aldehyde dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1981;20(26):7494–7501. doi: 10.1021/bi00529a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schomburg I, Chang A, Schomburg D. BRENDA, enzyme data and metabolic information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):47–49. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, et al. Structure of the formate transporter FocA reveals a pentameric aquaporin-like channel. Nature. 2009;462(7272):467–472. doi: 10.1038/nature08610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suppmann B, Sawers G. Isolation and characterization of hypophosphite—resistant mutants of Escherichia coli: identification of the FocA protein, encoded by the pfl operon, as a putative formate transporter. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11(5):965–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyle NR, Morgan JA. Computation of metabolic fluxes and efficiencies for biological carbon dioxide fixation. Metab Eng. 2011;13(2):150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka S, Sawaya MR, Yeates TO. Structure and mechanisms of a protein-based organelle in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;327(5961):81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1179513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penrod JT, Roth JR. Conserving a volatile metabolite: A role for carboxysome-like organelles in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(8):2865–2874. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2865-2874.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan C, et al. Short N-terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(16):7509–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, et al. Integrated electromicrobial conversion of CO2 to higher alcohols. Science. 2012;335(6076):1596. doi: 10.1126/science.1217643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MIT 2003 Registry of standard biological parts. Available at www.partsregistry.org. Accessed August 20, 2010.

- 27. Ginkgo Bioworks. Standard assembly of biobricks. Version 1.0. Available at ginkgobioworks.com/support/BioBrick_Assembly_Manual.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2013.

- 28.Shetty RP, Endy D, Knight TF., Jr Engineering BioBrick vectors from BioBrick parts. J Biol Eng. 2008;2(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosbacher TG, Mueller M, Schulz GE. Structure and mechanism of the ThDP-dependent benzaldehyde lyase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. FEBS J. 2005;272(23):6067–6076. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandt GS, et al. Snapshot of a reaction intermediate: Analysis of benzoylformate decarboxylase in complex with a benzoylphosphonate inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2009;48(15):3247–3257. doi: 10.1021/bi801950k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter F, Leaver-Fay A, Khare SD, Bjelic S, Baker D. De novo enzyme design using Rosetta3. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eiben CB, et al. Increased Diels-Alderase activity through backbone remodeling guided by Foldit players. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(2):190–192. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunkel TA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(2):488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buescher JM, Moco S, Sauer U, Zamboni N. Ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for fast and robust quantification of anionic and aromatic metabolites. Anal Chem. 2010;82(11):4403–4412. doi: 10.1021/ac100101d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleijn RJ, et al. Metabolic fluxes during strong carbon catabolite repression by malate in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(3):1587–1596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millard P, Letisse F, Sokol S, Portais J-C. IsoCor: Correcting MS data in isotope labeling experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(9):1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noor E, et al. Pathway thermodynamics highlights kinetic obstacles in central metabolism. PLOS Comput Biol. 2014;10(2):e1003483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schrödinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7. Available at www.pymol.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.