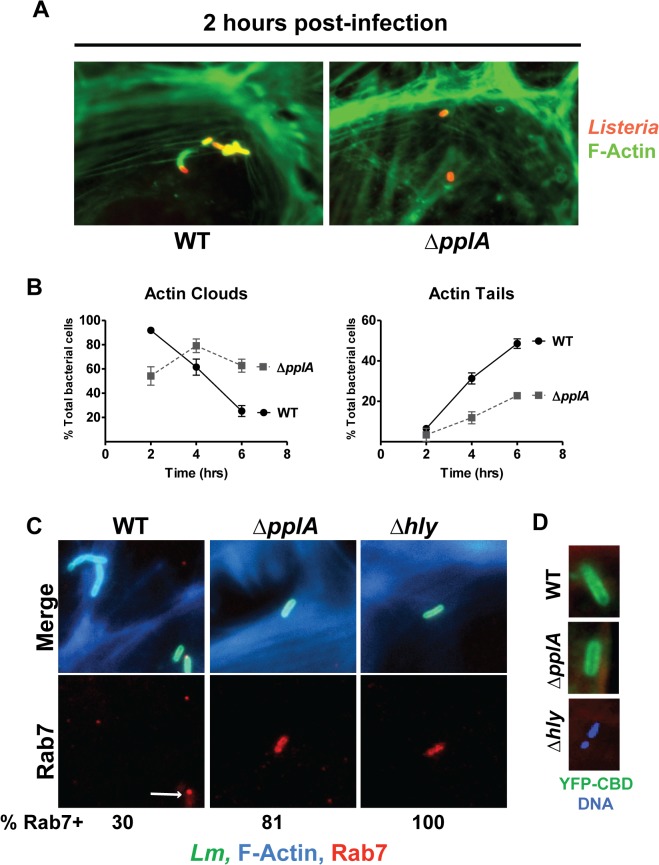

Fig 6. Loss of the pPplA pheromone delays escape from host cell vacuoles but does not impair vacuole perforation.

(A) Host cell actin localization as a measure of cytosolic L. monocytogenes during infection of PtK2 epithelial cells. Monolayers of PtK2s were infected as described for Fig. 5, except that an MOI of 20:1 was used. At 2, 4, and 6 hours p.i., Listeria infected host cells were fixed and bacteria were stained using a Listeria specific polyclonal antibody, followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to rhodamine (red stain). Host cell actin was stained using Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (green stain), which is a toxin that binds actin. Immunofluorescently labeled coverslips were then visualized on a Zeiss Axio Imager A2 microscope. Data shown is for 2 hours p.i. and is representative of 10 different fields from two independent experiments. (B) Quantification of actin clouds and actin tails formed by wild-type bacteria versus the ΔpplA mutant during intracellular growth in PtK2 cells. A total of 10 different fields, containing a total of 100 bacteria were assessed for clouds and tails. A ΔpplA mutant was delayed in recruitment of host-cell actin, consistent with a vacuole escape defect. (C) Co-localization studies of bacterial cells with host cell Rab7, a small GTPase associated with the late endosome. Ptk2 cells were infected and processed for microscopy as described above except that coverslips were removed at 1.5 hours post-infection and host cell F-actin was stained with phalloidin conjugated to Alexa-350 (blue), the secondary antibody used to stain Listeria cells was conjugated to Alexa-488 (green), and host cell Rab7 was stained with goat anti-Rab7 followed by a secondary donkey anti-goat antibody conjugated to Texas Red (red). Both the Δhly and ΔpplA mutants stained robustly with Rab7 and the majority of ΔpplA bacteria counted co-localized with Rab7, whereas only a small number of wild-type Listeria were positive for Rab7. A population of wild type bacteria also formed actin clouds at this early time. These results suggest the loss of the pPplA peptide results in bacterial mutants that are retained within vacuoles and which are delayed for entry into the cytosol. A minimum of 10 different fields containing a total of at least 100 bacteria in two independent experiments were counted for each strain. (D) The contribution of the pPplA peptide to vacuole membrane perforation was assessed during intracellular growth in PtK2 cells. PtK2 cells were transfected with a mammalian expression vector containing a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fused to the cell wall binding domain of a phage endolysin Ply118 (CBD) that binds with high affinity to the Listeria cell surface. YFP-CBD is stably expressed in the host cytosol and nucleus, and once intracellular L. monocytogenes perforates the vacuole membrane, YFP-CBD enters the vacuole and binds bacteria prior to escape into the cytosol. Transfected PtK2 cells were infected with bacteria as described for panel A, except coverslips were removed at 15 minutes post-infection and host cell-F-actin was stained with phalloidin conjugated to Texas Red (red), DNA with DAPI (blue), and bacteria were green if bound with YFP-CBD. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments. YFP-CBD binding of wild-type and the ΔpplA mutant but not Δhly bacteria indicates that vacuole perforation was not impaired by the loss of the pPplA peptide.