Abstract

Background and Objective

Several studies assessed the efficacy of traditional Chinese medical exercise in the management of Parkinson’s disease (PD), but its role remained controversial. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the evidence on the effect of traditional Chinese medical exercise for PD.

Methods

Seven English and Chinese electronic databases, up to October 2014, were searched to identify relevant studies. The PEDro scale was employed to assess the methodological quality of eligible studies. Meta-analysis was performed by RevMan 5.1 software.

Results

Fifteen trials were included in the review. Tai Chi and Qigong were used as assisting pharmacological treatments of PD in the previous studies. Tai Chi plus medication showed greater improvements in motor function (standardized mean difference, SMD, -0.57; 95% confidence intervals, CI, -1.11 to -0.04), Berg balance scale (BBS, SMD, -1.22; 95% CI -1.65 to -0.80), and time up and go test (SMD, -1.06; 95% CI -1.44 to -0.68). Compared with other therapy plus medication, Tai Chi plus medication also showed greater gains in motor function (SMD, -0.78; 95% CI -1.46 to -0.10), BBS (SMD, -0.99; 95% CI -1.44 to -0.54), and functional reach test (SMD, -0.77; 95% CI -1.51 to -0.03). However, Tai Chi plus medication did not showed better improvements in gait or quality of life. There was not sufficient evidence to support or refute the effect of Qigong plus medication for PD.

Conclusions

In the previous studies, Tai Chi and Qigong were used as assisting pharmacological treatments of PD. The current systematic review showed positive evidence of Tai Chi plus medication for PD of mild-to-moderate severity. So Tai Chi plus medication should be recommended for PD management, especially in improving motor function and balance. Qigong plus medication also showed potential gains in the management of PD. However, more high quality studies with long follow-up are warrant to confirm the current findings.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder with insidious onset. There is an estimation of at least 4 million people diagnosed as PD worldwide [1]. In China, PD is 1.70% in prevalence rate among people aged more than 65 years old [2]. Although the specific causes of PD are under investigation, incidence increases with age, especially after 50 years old [3]. The landmark symptoms of PD are resting tremor, bradykinesis, rigidity and decreased postural reflexes. These impairments lead to a decline in functional status as gait disturbance and balance decrements so that people with PD cannot cope with their daily tasks well [4–5]. It is reported that this decrease in functional status worsens as the disease progresses and often results in loss of independence and a decline in quality of life [6].

Although the precise reasons of the decrease in balance, gait and quality of life are still unknown, exercise is a preventive strategy that has demonstrated efficacy in PD [7,8]. Traditional Chinese medical exercise, including Qigong, Tai Chi, Wuqinxi, etc., combines body movements with mental focus. Tai Chi and Qigong, as representative traditional Chinese medical exercises, incorporate body movement, breath and mind training to maintain health and remove disease symptoms. Tai Chi, with slow body positions and dance-like movements that flow from one to the next continuously, promotes posture, flexibility, relaxation, well-being and mental concentration [9]. The difference between Qigong and Tai Chi is that Tai Chi is a martial art with movements practiced quickly which can provide self-defense and are externally focused. Meanwhile, Qigong cannot and it is internally focused [10].

In the last decade, Tai Chi and Qigong have been studied in the management of PD [11–15], but there were conflicting results. Li et al. reported significant improvements in balance, functional capacity and falls after Tai Chi exercise [14]. In contrast, Amano et al. concluded that Tai Chi was not effective in improving parkinsonian disability [15]. And previous reviews did not show consistent and strong evidence of Tai Chi for PD [16–19]. What’s more, there was no comprehensive systematic review of traditional Chinese medical exercise for PD.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to summarize and evaluate the evidence on the efficacy of traditional Chinese medical exercise for PD. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review summarizing the effect of traditional Chinese medical exercise for PD patients, focusing on motor function, gait and quality of life. Based on our findings, recommendations for future research are offered.

Methods

Search Strategy

The relevant studies were retrieved from the following online databases up to October 2014: PubMed, EMBASE, OVID-MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database, Weipu Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals and Wan Fang Data. The following keywords were used: Parkinson, Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism, traditional Chinese medical exercise, Tai Chi, Qigong, Wuqinxi, Baduanjin and Yijinjing. WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, ProQuest Dissertations and Chinese Dissertation Full-text Database were also searched to identify unpublished studies. And we contacted experts in relevant field. The literature search was performed independently by two authors (S Jiao and ZY Lv), and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Study Selection

Two authors (Y Yang and WQ Qiu) independently identified and selected the studies based on standardized manner. The studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials (non-RCTs); (2) the target population was diagnosed as PD in any stage; (3) traditional Chinese medical exercise was practiced alone or combined with stable medication, such as Madopar, compared to placebo, no intervention and any other therapies with or without stable medication; (4) the primary outcomes were motor function assessed by Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale III (UPDRS III), health related quality of life assessed by Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) or Activities of Daily Living (ADL), balance assessed by Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Functional Reach Test (FRT) or Time Up and Go Test (TUG) and gait assessed by gait velocity, stride/step length, or 6-Minute Walking Test (6-MWT); (5) the studies contain available data for the meta-analysis; (6) the paper was available in either English or Chinese. Any disagreement was settled by discussion or by consulting a third author (J Teng).

Data Extraction

Two authors (Y Yang and WQ Qiu) independently performed data extraction from the eligible studies. The following information was extracted: (1) study source and study design; (2) patients characteristics: sample size, age, gender and disease stage; (3) details of the interventions: type, duration, dose and frequency; (4) main outcomes and (5) length of follow-up. For the crossover study, the first phase of the study was adopted for the sake of prohibiting carryover effects. The primary author was contacted by e-mails when the relevant data was not reported. Any disagreement was settled by discussion or by consulting a third author (YL Hao).

Quality Assessment

Two authors (Y Yang and S Jiao) independently assessed the methodological quality of eligible studies using PEDro scale. The PEDro score has a fair-to-good reliability for the physiotherapy studies in systematic reviews [20,21]. And higher scores represent a better quality. The necessary information in eligible studies was supplemented by contacting the corresponding authors. There was no disagreement between the authors regarding PEDro scores.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted with Cochrane Collaboration software (Review Manager Version 5.1). D-value of the pre and post treatment was used as the change of curative effect. As for three or four-armed studies, the similar control groups have be merged with computational formula provided by the Cochrane handbook to create a single pair-wise comparison. For continuous data, standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of random-effects model were calculated for all eligible trials. The I 2 statistic, a quantitative measure of inconsistency across studies, was employed in assessing heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was regarded high if the I 2 is greater than 75%. Detailed subgroup analyses were performed to compare Tai Chi/Qigong plus medication with medication alone or other therapy plus medication. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot if the group included more than 10 studies.

Results

Study Selection

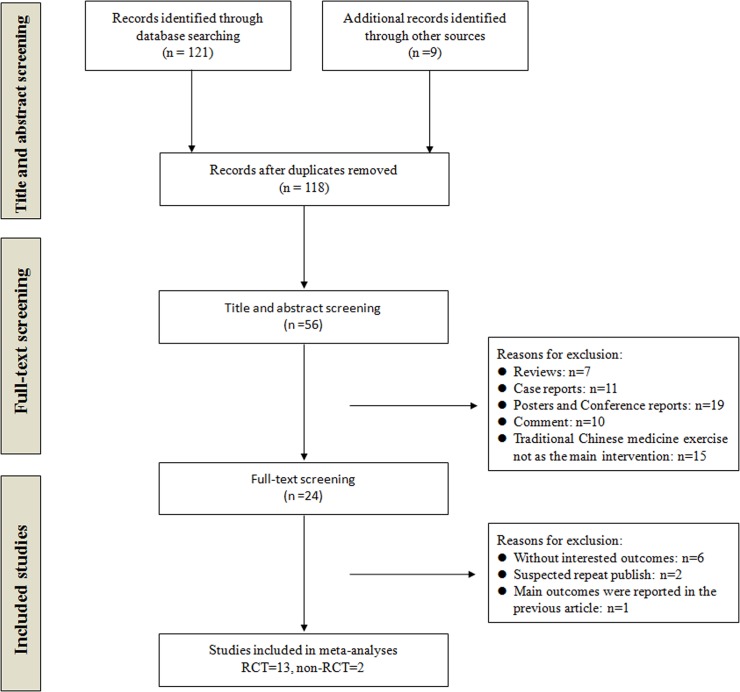

A total of 118 records were identified after removing duplicates. During the preliminary screening of the titles and abstracts, 62 studies were eliminated. After full-texts screening, 13 RCTs [11,13–15,21–25,27–31] and 2 non-RCTs [12,26] were included in our review. 9 studies were published in English [13–15,22–24,27,28,31] and 6 in Chinese [11,12,25,26,29,30]. The studies were excluded due to without interested outcomes (n = 6), suspected repeat publication (n = 2) and repeated report of main outcomes (n = 1). The detailed process of search and identification was shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Study Characteristics

A total of 799 participants with the mean age of 64.57 ± 4.88 years were included. The patients in most studies were diagnosed as PD of mild-to-moderate severity. The patients in 10 studies [13,15,22–28,31] were diagnosed as Hoehn and Yahr stage I to III and patients in 2 studies [14,30] were Hoehn and Yahr stage I to IV. The other studies [11,12,28] did not report the Hoehn and Yahr stage of eligible patients, but the patients can finish Qigong or Tai Chi exercise independently. Qigong [11–13,29] or Tai Chi [14,15,22–28,30–31] was employed as assisting pharmacological therapies in the included studies. The control interventions included medication [11,12,15,22,23,27,28,30,31], stretching/resistance training plus medication [14], dancing plus medication [23], walking plus medication [25,26] and other exercises plus medication [13,24,27,29]. The intervention time ranged from 4 weeks to 50 weeks. The details of study characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study source | Design | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Gender (M/F) | Disease stage (Hoehn and Yahr stage) | Follow-up (weeks) | Duration (weeks) | Main outcome | Experimental group intervention | Control group intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu 1998, China [11] | RCT | 83 | 58±11;71±10 | 38/14;29/2 | NR | — | 50 | Webster scale | Qigong plus medication (30min/700sessions) | Medication |

| Gu 2002, China [12] | Non RCT | 51 | 57±9;51±12 | 23/10;17/7 | NR | 36 | 12 | Webster scale | Qigong plus medication (30min/168sessions) | Medication |

| Burini 2006, Italy [13] | RCT | 26 | 65.7±7;62.7±4 | 5/8;4/9 | 2–3 | — | 7 | UPDRS, 6-MWT, PDQ-39 | Qigong plus medication(45min/20sessions) | Aerobic exercise plus medication(45min/20sessions) |

| Hackney 2008, US [22] | RCT | 26 | 64.9±8.3;61.7±10.1 | 12/2; 9/3 | 2±0.46;2±0.3 | — | 13 | UPDRS III, BBS, Gait, TUG, 6-MWT | Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/20sessions) | Medication |

| Hackney 2009, US [23] | RCT | 61 | 66.8±2.4;68.2±1.4;64.9±2.3;66.5±2.8 | 11/6;11/3;11/2;12/5 | 2.0±0.2;2.1±0.1;2.0±0.1;2.2±0.2 | — | 13 | PDQ-39 | Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/20sessions) | 1) Tango plus medication;2) Waltz/Foxtrot plus medication(60min/20sessions);3) Medication |

| Gladfelter 2011, US [24] | RCT | 17 | 72±8.52 | 12/5 | 2.4±0.87 | — | 12 | BBS, FRT, TUG, PDQ-39 | Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/12sessions) | Physical exercise plus medication |

| Li 2011, China [25] | RCT | 47 | 68.28±6.62; 67.13±6.73 | 11/13;11/12 | 2.5–3 | — | 8 | UPDRS III, BBS, PDQ-39 | Tai Chi plus medication(30-45min/80sessions) | Walking plus medication(40min/80sessions) |

| Zhu 2011, China [26] | RCT | 38 | 63.35±8.72; 64.83±9.29 | 11/9;12/8 | 1–2 | — | 4 | UPDRS III, BBS | Tai Chi plus medication(30-45min/40sessions) | Walking plus medication(40min/40sessions) |

| Li 2012, US [14] | RCT | 195 | 68±9; 69±8; 69±9 | 45/20; 38/27;39/26 | 1–4 | 12 | 24 | UPDRS III, Gait, FRT, TUG | Tai Chi plus medication(60min/48sessions) | 1) Stretching plus medication;2) Resistance training plus medication(60min/48sessions) |

| Amano 2013, US [15] | RCT | 45 | 64±13; (66±11);68±7; 66±7 | 7/5(7/8);7/2;7/2 | 2.3±0.4(2.4±0.6);2.2±0.4;2.4±0.4 | — | 16 | UPDRS III, Gait | 1) Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/32-48sessions);2) Qigong plus medication(60min/32sessions) | Medication |

| Cheon 2013, Korea [27] | Non-RCT | 23 | 62.3±6.5;65.6±7.9;64.9±7.2 | 0/23 | 2–3 | — | 8 | UPDRS, ADL | Sun-style Tai Chi plus medication(50-65min/24sessions) | 1) Medication2) Exercise plus medication(60min/24sessions) |

| Choi 2013, Korea [28] | RCT | 20 | 60.81±7.6;65.54±6.8 | NR | 1.6±0.6;1.8±0.3 | — | 12 | UPDRS, TUG,6-MWT, OLS, ADL | Tai Chi plus medication(60min/36sessions) | Medication |

| Cheng 2014, China [29] | RCT | 66 | 57±9;51±12 | 23/10;17/16 | NR | — | 12 | UPDRS, 6-MWT | Qigong plus medication (60min/24sessions) | Routine exercise plus medication (60min/24sessions) |

| Gao 2014, China [30] | RCT | 80 | 69.54±7.32;68.28±8.53 | 23/14;27/12 | 1–4 | 24 | 12 | UPDRS III, BBS, TUG | Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/36sessions) | Medication |

| Nocera 2014, US [31] | RCT | 21 | 66±11;65±7 | 7/8;4/2 | 2–3 | — | 16 | PDQ-39 | Yang-style Tai Chi plus medication(60min/48sessions) | Medication |

RCT = randomized controlled trial; NR = no reported; Non-RCT = non-randomized controlled trial; 6-MWT = 6-minute walking test; UPDRS = unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale; BBS = berg balance scale; TUG = timed up and go; PDQ-39 = Parkinson’s disease questionnaire-39; FRT = functional reach test; ADL = activities of daily living; OLS = one-leg standing time.

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of the included studies was presented in Table 2. The total scores on the PEDro scale ranged from 3 to 8 points. Randomized allocation was employed in most studies (87%) [11,13–15,22–26,28–31], but only 4 trials were considered as allocation concealment due to lack of detailed descriptions [13,15,25,30]. None of the studies blinded the therapists or subjects, but independent assessors, who were unaware of the allocation, were employed in most studies (80%) [13–15,22–26,28–31]. 6 studies definitely showed a high expulsion rate over 15% [13,22–25,27]. And 4 studies used the intention-to-treat analysis [11,12,14,15]. The eligible studies showed good methodological quality in the remaining items of PEDro scale. Funnel plot analysis was not performed because none of the groups included more than 10 trials.

Table 2. PEDro scale of quality for included trials.

| Study | Eligibility criteria | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Similar atbaseline | Subjects blinded | Therapists blinded | Assessors blinded | <15%dropouts | Intention-to-treat analysis | Between-group comparisons | Point measures and variability data | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu 1998 [11] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Gu 2002 [12] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Burini 2006 [13] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Hackney 2008 [22] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Hackney 2009 [23] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Gladfelter 2011 [24] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Li 2011 [25] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Zhu 2011 [26] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Li 2012 [14] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Amano 2013 [15] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Cheon 2013 [27] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Choi 2013 [28] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Cheng 2014 [29] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Gao 2014 [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nocera 2014 [31] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

Criteria (2–11) were used to calculate the total PEDro score. Each criterion was scored as either 1 or 0 according to whether the criteria was met or not, respectively.

The Effect of Tai Chi for PD

Motor function

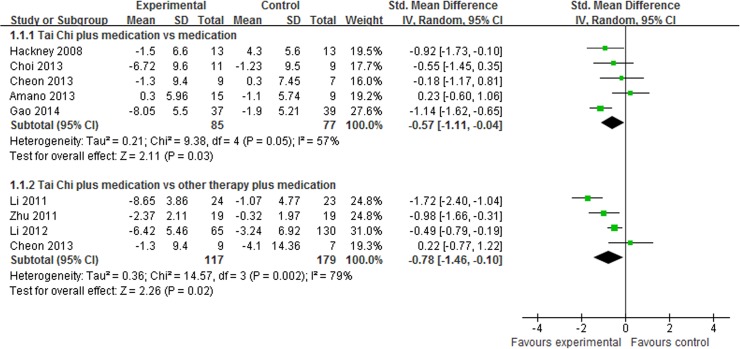

UPDRS III was reported in 8 studies [14,15,22,25–28,30], and subgroup analysis was performed. Most of them reported that Tai Chi plus medication showed beneficial effect in UPDRS III. The aggregated result also indicated that Tai Chi plus medication showed greater improvements in UPDRS III than medication alone (SMD, -0.57; 95% CI -1.11 to -0.04; p = 0.03, Fig 2) [15,22,27,28,30] and other therapy plus medication (SMD, -0.78; 95% CI -1.46 to -0.10; p = 0.02, Fig 2) [14,25–27].

Fig 2. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication in motor function.

Balance

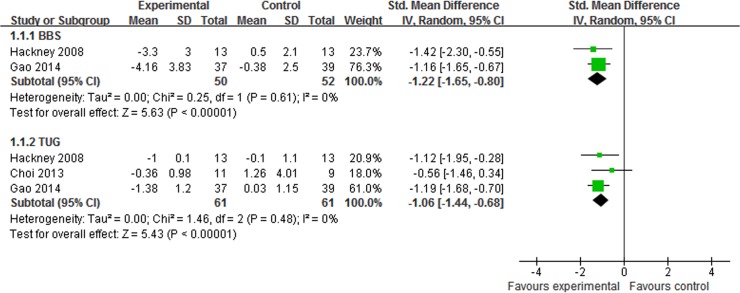

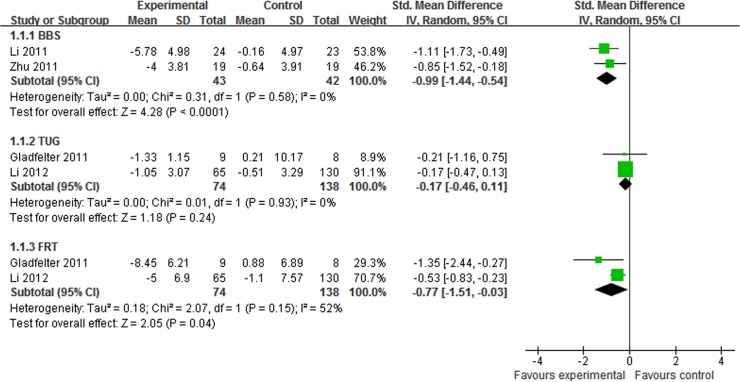

7 studies assessed the effect of Tai Chi plus medication in improving balance in patients with PD [14,22,24–26,28,30]. The aggregated result indicated that Tai Chi plus medication showed greater improvements on BBS (SMD, -1.22; 95% CI -1.65 to -0.80; p<0.00001, Fig 3) [22,30] and TUG (SMD, -1.06; 95% CI -1.44 to -0.68; p<0.00001, Fig 3) [22,28,30] than medication alone. Compared with other therapy plus medication, Tai Chi plus medication also showed greater improvements on BBS (SMD, -0.99; 95% CI -1.44 to -0.54; p<0.0001, Fig 4) [25,26] and FRT (SMD, -0.77; 95% CI -1.51 to -0.03; p = 0.04, Fig 4) [14,24], but not on TUG (SMD, -0.17; 95% CI -0.46 to 0.11; p = 0.24, Fig 4) [14,24]

Fig 3. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication in balance compared with medication alone.

BBS = berg balance scale; FRT = functional reach test;TUG = timed up and go.

Fig 4. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication in balance compared with other therapy plus medication.

BBS = berg balance scale; FRT = functional reach test; TUG = timed up and go.

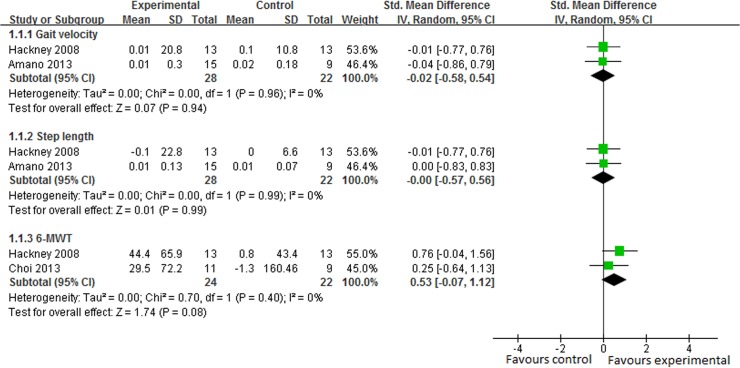

Gait

In 5 studies, gait function was assessed by gait velocity and step length [14,15,22] and gait endurance was assessed by 6-MWT [22,28]. The subgroup analysis suggested that there was no significant difference between Tai Chi plus medication and medication alone in gait velocity (SMD, -0.02 95% CI -0.58 to 0.54; p = 0.94, Fig 5) [15,22], step length (SMD, -0.00 95% CI -0.57 to 0.56; p = 0.99, Fig 5) [15,22] or 6-MWT (SMD, 0.53 95% CI -0.07 to 1.12; p = 0.08, Fig 5) [22,28]. However, one study reported that Tai Chi plus medication group performed better in gait velocity and step length than stretching plus medication group, and outperformed the resistance-training plus medication group in step length [14].

Fig 5. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication in gait velocity, step length and 6-minute walking test (6-MWT) compared with medication alone.

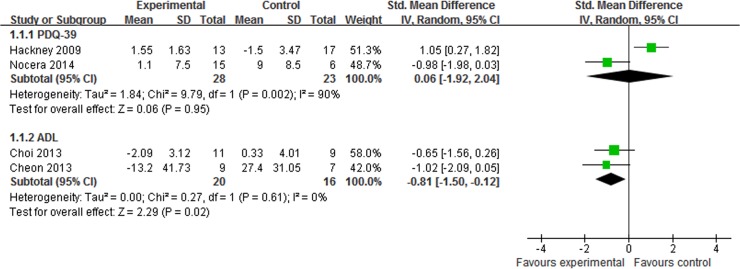

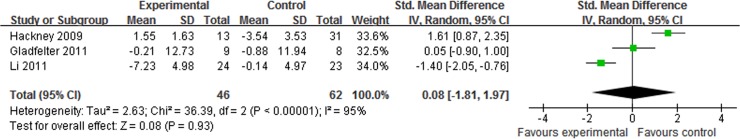

Quality of life

The quality of life was assessed in 6 trials [23–25,27,28,31], and the subgroup analysis was performed. Tai Chi plus medication showed greater improvements than medication alone on ADL (SMD, -0.81 95% CI -1.50 to -0.12; p = 0.02, Fig 6) [27,28]. On PDQ-39, however, the aggregated result indicated that there was no significant difference between Tai Chi plus medication and medication alone (SMD, 0.06 95% CI -1.92 to 2.04; p = 0.95, Fig 6) [23,31] or other therapy plus medication (SMD, 0.08 95% CI -1.81 to 1.97; p = 0.93, Fig 7) [23–25].

Fig 6. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication in quality of life compared with medication alone.

PDQ-39 = Parkinson’s disease questionnaire-39; ADL = activities of daily living.

Fig 7. The effect of Tai Chi plus medication on Parkinson’s disease questionnaire-39 compared with other therapy plus medication.

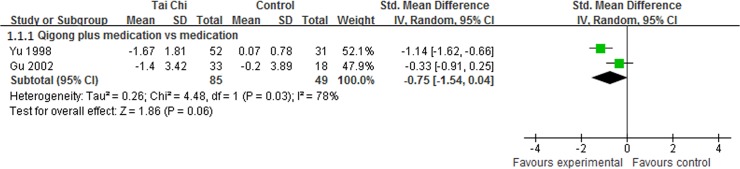

The Efficacy of Qigong for PD

Webster scale

Webster scale is a comprehensive scale accessing clinical symptoms, quality of life and motor function in patients with PD. 2 studies reported that Qigong plus medication showed favorable improvements in Webster scale [11,12]. The meta-analysis indicated that Qigong plus medication demonstrated a small, but not statistically significant effect in Webster scale compared with medication alone (SMD, -0.75; 95% CI -1.54 to 0.04; p = 0.06, Fig 8) [11,12].

Fig 8. The effect of Qigong plus medication in Webster scale.

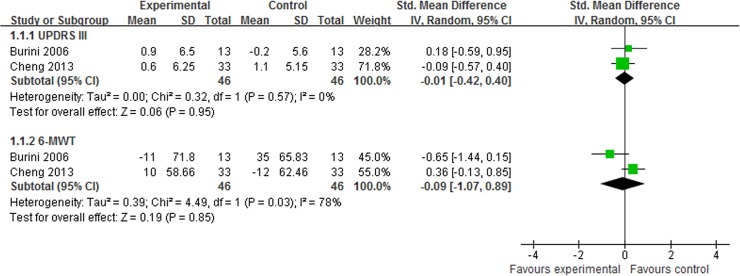

Motor function

UPDRS III was reported in 3 trials [13,15,29]. One study reported that Qigong plus medication showed better effect than medication alone (UPDRS III mean changes: 3.4 versus 1.1) [15]. However, the meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference between Qigong plus medication and other therapy plus medication (SMD, -0.01; 95% CI -0.42 to 0.40; p = 0.95, Fig 9) [13,29].

Fig 9. The effect of Qigong plus medication in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale III (UPDRS III) and 6-minute walking test.

Gait

One study reported that Qigong plus medication did not show greater improvements than medication alone in gait velocity or step length [15]. Gait endurance was assessed by 6-MWT in 2 trials [13,29] and the meta-analysis was performed. The aggregated result showed that there was no significant difference between Qigong plus medication and other therapy plus medication (SMD, -0.09; 95% CI -1.07 to 0.89; p = 0.85, Fig 9) [13,29].

Quality of life

One study assessed the quality of life in patients with PD by PDQ-39, and reported that Qigong plus medication showed better effect than aerobic exercise plus medication (PDQ-39 mean changes: 2.8 versus -3.2) [13].

Adverse Events

No serious adverse events were reported during the Tai Chi/Qigong training in eligible studies. Only one study reported that there were few back pain and ankle sprain [14].

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effect of traditional Chinese medical exercise in the management of PD. Tai Chi and Qigong were used as assisting pharmacological treatments of PD in the previous studies. The positive finding was that Tai Chi plus medication showed greater gains than medication alone or other therapy plus medication in motor function and balance. However, there was not sufficient evidence on the efficacy of Tai Chi plus medication in improving gait or quality of life. Although some trials reported beneficial effect of Qigong plus medication for PD, the aggregated results did not support or refute it.

The positive finding of this systematic review should be available for patients with PD of mild-to-moderate severity due to most patients diagnosed as Hoehn and Yahr stage I to III [13,15,22–28,31]. All eligible patients can finish Tai Chi or Qigong exercise independently. And traditional Chinese medical exercise is based on the ability to stand and move independently. Therefore, these assisting pharmacological exercises should be recommended for PD patients of mild-to-moderate severity, especially in improving motor function and balance.

The last systematic reviews of Tai Chi for PD concur with our positive findings [17,18]. One supported that Tai Chi plus medication resulted in promising gains in mobility and balance for PD patients at an early stage [18]. However, there were serious limitations in this review. Firstly, two control interventions were considered as no intervention [15] and routine physical exercise [24] respectively, but stable medications were not changed during the study according to the author’s reply. Secondly, some subgroup analyses only included one trial. It was not valid because the meta-analysis should be performed based at least on two studies. What’s more, the similar control groups should be combined to create a single pair-wise comparison according to Cochrane handbook, but it was not performed in this review. The other review concluded that Tai Chi was a valid complementary and alternative therapy for PD, especially on motor function and balance [17]. However, Tai Chi as an assisting pharmacological treatment was not compared with medication alone or other therapy plus medication. In our review, detailed subgroup analyses were performed to compare Tai Chi plus medication with medication alone or other therapy plus medication.

Our results were different from some previous reviews [16,19]. Lee’s review concluded that there was no sufficient evidence to support Tai Chi in the management of PD [16], but it was only a qualitative review including 3 RCTs [32–34], 1 non-RCT [35], and 3 uncontrolled clinical trials [36–38] published between 1997 and 2007. And most of them were published by conference abstracts without detailed information [32–36]. Although the meta-analysis was performed in Toh’s systematic review [19], it only included 4 RCTs [14,15,22,23]. The main suspected reason of the difference was that numerous studies of Tai Chi for PD were published from 2008 to 2014 [14,15,22–28,30,31]. So current update provided stronger evidence of Tai Chi plus medication for PD.

Our result of Qigong for PD was supported by previous review [39]. The evidence was insufficient to support Qigong plus medication for PD due to limited number of studies. However, the beneficial finding of current review was that Qigong plus medication showed potential gains for PD. Two trials reported that Qigong plus medication showed better effect than medication alone in Webster scale [11,12], and one study reported that Qigong plus medication was superior to aerobic exercise plus medication in UPDRS III and PDQ-39 [13]. What’s more, it has been reported that Qigong has beneficial effects in improving physical performance, figure, quality of life, etc. [40–42]. Consequently, Qigong may be a valid assisting pharmacological treatment of PD. Further high quality RCTs are required to confirm current beneficial finding.

In previous studies, only Tai Chi and Qigong were focused, but other traditional Chinese medical exercises should also be investigated, such as Baduanjin and Wuqinxi. Li and his colleagues have reported beneficial effects of Baduanjin exercise in physical flexibility of healthy older [43]. Baduanjin has been recommended as a safe and feasible treatment option for patients with knee OA in disability, stiffness and quality of life [44]. Wuqinxi exercise may be a valid alternative treatment for low back pain in improving dysfunction [45], and for knee OA in balance function [46]. So Baduanjin and Wuqinxi exercise may be a valid assisting pharmacological treatment for PD.

Assuming that traditional Chinese medical exercise was beneficial for PD, some complex neurophysiological mechanisms may provide possible rationales [47–50]. Intensive exercise showed beneficial effects on neural plasticity, neuroprotection and preventing neural degeneration [47]. Especially, some animal studies have reported that intensive exercise may promote neurogenesis, dopamine synthesis and release in the striatum [51,52]. And such neural changes may affect behavioral recovery in individuals with PD [53,54]. In relevant studies, the intervention was generally considered as intensive exercise when involving 2–3 hours of exercise per week for 6–14 weeks (a total of 12–42 hours of treatment) [47]. In our systematic review, all eligible studies employed intensive traditional Chinese medical exercise (a total of 12–300 hours) for PD. And the intensive Tai Chi/Qigong also showed beneficial effects in improving motor function and balance. In addition, repetitive traditional Chinese medical exercise may also promote development of new motor programs which allow faster reactions responding to postural challenge [55]. And these new motor programs, which promoted behavioral recovery, may be due to making new synaptic connections.

There were some potential limitations in our systematic review: 1) there was the degree of uncertainty in locating relevant studies because of limited retrieving resources, language barrier, publication bias, etc. 2) there were few studies in some subgroup analyses because of strict eligibility criteria, which may bias the aggregated results. However, low eligibility criteria would conduct more doubtful results. 3) PEDro score was less than 6 in 5 studies. They were not considered as high quality, but they contributed valuable information to the evidence of Tai Chi/Qigong for PD. So they were included in our review. 4) synthetic results may be affected by different parameters (duration, frequency, dosage, etc.) of Tai Chi/Qigong exercise. 5) the follow-up effect of Tai Chi/Qigong for PD was not investigated in current studies. So further studies of Tai Chi/Qigong for PD should include long-term follow-up. 6) few adverse events were reported in included studies, but it was not concluded that Tai Chi/Qigong exercise was safe.

Conclusions

In the previous studies, Tai Chi and Qigong were used as assisting pharmacological treatments of PD. The current systematic review showed positive evidence of Tai Chi plus medication for PD of mild-to-moderate severity. So Tai Chi plus medication should be recommended for PD management, especially in improving motor function and balance. Qigong plus medication also showed potential gains in the management of PD. However, more high quality studies with long follow-up are warrant to confirm the current findings. And relevant mechanism research of traditional Chinese medical exercise for PD is also required.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Fund Projects of China (81271398). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008; 79:368–376. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang ZX, Roman GC, Hong Z, Wu CB, Qu QM. Parkinson’s disease in China : prevalence in Beijing, Xian, and Shanghai. Lancet. 2005; 365:595–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, Fross RD, Leimpeter A. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 157:1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hausdorff JM. Gait dynamics in Parkinson’s disease: Common and distinct behaviour among stride length, gait variability, and fractal-like scaling. Chaos. 2009; 19: 026113 10.1063/1.3147408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen NE, Sherrington C, Paul SS, Canning CG. Balance and Falls in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-analysis of the Effect of Exercise and Motor Training. Mov Disord. 2011; 26:1605–1615. 10.1002/mds.23790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Temlett JA, Thompson PD. Reasons for admission to hospital for Parkinson’s disease. Intern Med J. 2006; 36:524–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Effects of dance on movement control in Parkinson’s disease: a comparison of Argentine tango and American ballroom. J Rehabil Med. 2009; 41:475–481. 10.2340/16501977-0362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canning CG, Allen NE, Dean CM, Goh L, Fung VS. Home-based treadmill training for individuals with Parkinson's disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clinl Rehabil. 2012; 26:817–826. 10.1177/0269215511432652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li F, Harmer P, McAuley E, Fisher KJ, Duncan TE, Duncan SC. Tai chi, self-efficacy, and physical function in the elderly. Prev Sci. 2001; 2:229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B. Meditation practices for health: state of the research. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2007; 155:1–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu XH, Xu JF, Shao DY, Fa ZG, Chen GZ. Clinical trial of Qigong for Parkinson’s disease. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 1998; 7:303–304. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu AM, Huang JM, Chen XS, Zhang JS, Lou FY. A pilot study of auditory P300 in Parkinson’s disease. Henan Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases. 2002; 5:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burini D, Farabollini B, Iacucci S, Rimatori C, Riccardi G. A randomized controlled cross-over trial of aerobic training versus Qigong in advanced Parkinson's disease. Eura Medicophys. 2006; 42:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, Eckstrom E, Stock R. Tai Chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:511–519. 10.1056/NEJMoa1107911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Amano S, Nocera JR, Vallabhaosula S, Juncos JL, Gregor RJ. The effect of Tai Chi exercise on gait initiation and gait performance in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013; 19:955–960. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee MS, Lam P, Ernst E. Effectiveness of tai chi for Parkinson’s disease: a critical review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008; 14:589–594. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Li XY, Gong L, Zhu YL, Hao YL. Tai Chi for improvement of motor function, balance and gait in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One. 2014; 10.1371/journal.pone.0102942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Ni X, Liu S, Lu F, Shi X, Guo X. Efficacy and safety of Tai Chi for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Plos One. 2014; 10.1371/journal.pone.0099377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Toh SFM. A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Tai Chi Exercise in Individuals with Parkinson's Disease from 2003 to 2013. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 23:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy. 2003; 83:713–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Macedo LG, Elkins MR, Maher CG, Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C. There was evidence of convergent and construct validity of physiotherapy evidence database quality scale for physiotherapy trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010; 63:920–925. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Tai Chi improves balance and mobility in people with Parkinson disease. Gait Posture. 2008; 28:456–460. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hackney ME, Earhart GM. Health-related quality of life and alternative forms of exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009); 15:644–648. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gladfelter BA. The effect of Tai Chi exercise on balance and falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease [dissertation]. Valparaiso University, Valparaiso, Indiana, 2011.

- 25.Li JX. The motion control effect of Parkinson’s disease patient treating by Taijiquan [dissertation]. Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China, 2011.

- 26. Zhu Y, Li JX, Li N, Jin HZ, Hua L. Effect of Taijiquan on motion control for Parkinson’s disease at early stage. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2011; 17:355–358. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheon SM, Chae BK, Sung HR, Lee GC, Kim JW. The efficacy of exercise programs for Parkinson’s disease: Tai Chi versus combined exercise. J Clin Neurol. 2013; 9:237–243. 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.4.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi HJ, Garber CE, Jun TW, Jin YS, Chung SJ. Therapeutic effects of tai chi in patients with Parkinson’s disease. ISRN Neurol. 2013; 10.1155/2013/548240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Cheng L. The effect of Qigong for Parkinson’s disease in motor function [dissertation]. Yunnan College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Kunming, China, 2014.

- 30.Gao Q, Leung A, Yang Y, Wei Q, Guan M. Effects of Tai Chi on balance and fall prevention in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil (In press), 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Nocera JR, Amano S, Vallabhajosula S, Hass CJ. Tai Chi exercise to improve non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2014; 10.4172/2157-7595.1000137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Marjama-Lyons J, Smith L, Myal B, Nelson J, Holliday G. Tai Chi and reduced rate of falling in Parkinson’s disease: a single blinded pilot study. Mov Disord. 2002; 17:S70–71. 11836760 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hass CJ, Waddell DE, Wolf SL, Juncos JL, Gregor RJ. The influence of tai chi training on locomotor ability in parkinson’s disease. Annual Meeting of American Society of Biomechanics. 2006; Available: http://www.asbweb.org/conferences/2006/pdfs/154.pdf. Accessed 2014 April 8.

- 34. Purchas MA, MacMahon DG. The effects of Tai Chi training on general wellbeing and motor performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Mov Disord. 2007; 22:S80. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheon SM, Sung HR, Ha MS, Kim JW. Tai Chi for physical and mental health of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Proceeding of the first international conference of tai chi for health. Seoul, Korea. 2006; pp.68.

- 36. Welsh M, Kymn M, Walters CH. Tai Chi and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord.1997; 12(Suppl 1):137. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li F, Harmer P, Fisher KJ, Xu J, Fitzgerald K. Tai Chi based exercise for older adults with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot program evaluation. J Aging Phys Act. 2007; 15:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sung HR, Yang JH, Kang MS. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan exercise on updrs-me, function fitness, bdi and qol in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Kor J Phys Edu. 2006; 45:583–590. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee MS, Ernst E. Qigong for movement disorders: A systematic review. Mov Disord. 2009; 24:301–303. 10.1002/mds.22275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ding M, Zhang W, Li K, Chen X. Effectiveness of t’ai chi and qigong on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2014; 20:79–86. 10.1089/acm.2013.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zeng Y, Luo T, Xie H, Huang M, Cheng AS. Health benefits of qigong or tai chi for cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2014; 22:173–186. 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauche R, Cramer H, Häuser W, Dobos G, Langhorst J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of qigong for the fibromyalgia syndrome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013; 10.1155/2013/635182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Li R, Jin L, Hong P, He ZH, Huang CY. The effect of baduanjin on promoting the physical fitness and health of adults. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; 10.1155/2014/784059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44. An B, Dai K, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Hao Y. Baduanjin alleviates the symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2008; 14:167–174. 10.1089/acm.2007.0600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang F, Bai YH, Zhang J. The influence of “wuqinxi” exercises on the lumbosacral multifidus. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014; 26:881–884. 10.1589/jpts.26.881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian BW. A study on the effect of Wuqinxi exercise on the proprioception and balance function of elderly female patients with KOA [dissertation]. Beijing Sports University. Beijing, China, 2012.

- 47. Frazzitta G, Balbi P, Maestri R, Bertotti G, Boveri N, Pezzoli G. The beneficial role of intensive exercise on Parkinson disease progression. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013; 92:523–532. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31828cd254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, Jakowec MW. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013; 12:716–726. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. King LA, Horak FB. Delaying mobility disability in people with Parkinson disease using a sensorimotor agility exercise program. Phys Ther. 2009; 89:384–393. 10.2522/ptj.20080214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lan C, Chen SY, Lai JS, Wong AM. Tai Chi Chuan in medicine and health promotion. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013; 10.1155/2013/502131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999; 2:266–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Heyes MP, Garnett ES, Coates G. Nigrostrital dopaminergic activity is increased during exhausitive exercise stress in rats. Life Sci. 1988; 42:1537–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tillerson JL, Caudle WM, Reverón ME, Miller GW. Exercise induces behavioral recovery and attenuates neurochemical deficits in rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2003; 119:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fisher BE, Petzinger GM, Nixon K, Hogg E, Bremmer S. Exercise-induced behavioral recovery and neuroplasticity in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned mouse basal ganglia. J Neurosci Res. 2004; 77:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacLaggan L. The impact of tai chi chuan training on the gait, balance, fear of falling, quality of life, and tremor in four women with moderate idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. The thesis of Master of Science in Physiotherapy. Halifax: Dalhousie University, 2000.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.