Abstract

Three new triazole conjugates derived from D-mannose were synthesized and assayed in in vitro assays to investigate their ability to inhibit α-mannosidase enzymes from the glycoside hydrolase (GH) families 38 and 47. The triazole conjugates were more selective for a GH47 α-mannosidase (Aspergillus saitoi α1,2-mannosidase), showing inhibition at the micromolar level (IC50 values of 50-250 μM), and less potent towards GH38 mannosidases (IC50 values in the range of 0.5-6 mM towards jack bean α-mannosidase or Drosophila melanogaster lysosomal and Golgi α-mannosidases). The highest selectivity ratio [IC50(GH38)/IC50(GH47)] of 100 was exhibited by the triazole conjugate 6. To understand structure-activity properties of synthesized compounds, 3-D complexes of inhibitors with α-mannosidases were built using molecular docking calculations.

Keywords: Click reaction; 1-(d-Mannopyranosyl)-1,2,3-triazole; α-Mannosidase inhibitor; Molecular docking; Glycoside hydrolase

1. Introduction

In recent years the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction became a powerful tool for an exclusive formation of the 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles.1-3 A broad applicability of the reaction has been demonstrated in the field of material science,4 chemical biology,5 medicinal chemistry,6-7 and later also in the field of carbohydrate chemistry. Many of the synthesized carbohydrate mimetics were active against various biological targets.8-13

One group of these mimetics derived from glycosyl azides has been a subject of extensive investigation. The interest in these simple glycoside mimetics has been supported by a high stability of the glycosyl-triazole linkage under various conditions, including hydrolysis.14 They exhibited interesting biological activities as inhibitors of galectins,15,16 glycogen phosphorylase,17 carbonic anhydrase18,19 and O-GlcNAcase,20 or as antimycobacterial21 and anticancer agents.22 Their cytotoxic activity23 and binding affinities to lectins24 have also been investigated. Moreover, the ability of these mimetics to inhibit the enzymatic activity of commercial glycosidases, such as sweet almond β-glucosidase,25,26 yeast α-glucosidase,26 Escherichia coli β-galactosidase,25 and bovine liver β-galactosidase25 has been studied.

The processing of N-linked oligosaccharides by α-mannosidases in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex is a process conserved in plants and animals.27 α-Mannosidases are enzymes that remove non-reducing terminal mannose residues from glycoconjugates,28 of which, there are two major homology-based classes.27 The class I enzymes (the GH family 47) are present in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi and are responsible for the initial trimming of N-glycans to yield Man5-9GlcNAc2 structures; the class II enzymes (the GH family 38) are more heterogeneous and encompass Golgi enzymes that are involved in processing of hybrid and complex N-glycans to result in GlcNAcMan3GlcNAc2 as well as lysosomal and cytosolic enzymes involved in catabolism of glycoproteins. During cancer metastasis, the degree of branching of N-linked carbohydrate structures has been correlated with malignancy and disease progression through a disruption of normal intracellular interactions and effectively concealing cancerous cells from immune detection.29

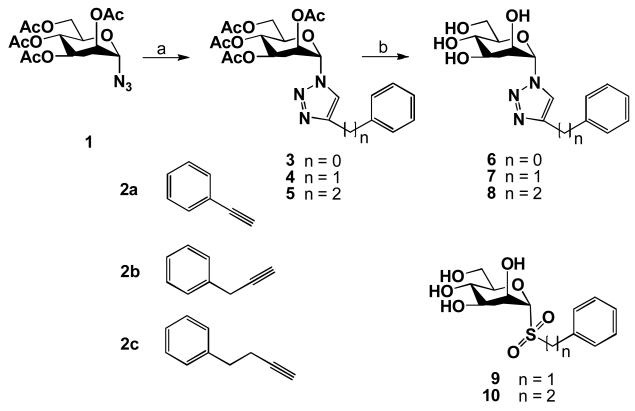

Glycosyltriazole mimetics with α-linked mannose as the core structure are suitable compounds for investigation of inhibitory activity towards α-mannosidases. We have previously reported the synthesis of α-mannosides differing in the aglycone, and examined their inhibitory effect towards two α-mannosidases, Drosophila melanogaster homologs of human Golgi mannosidase II (dGMIIb) and human lysosomal mannosidase (dLManII).30 Due to the presence of cis positioned hydroxyl groups, d-mannose is an essential part of the native substrate of GMII and its binding with the Zn2+ co-factor at the active site of GMII has been previously characterized by crystallographic measurements.31-33 We found that mannosides with a phenylalkylsulfonyl aglycone were weak GMII and LM inhibitors (IC50 = 1-3 mM). In addition, one of them, benzyl α-d-mannopyranosyl sulfone 9 was selective towards GMII. In our ongoing research, we focused on a simple modification of the aglycone and the phenylalkylsulfonyl function was replaced with another hydrolytically stable triazolylphenylalkyl one. Three mannose conjugates were synthesized and tested for their ability to act as inhibitors of dGMIIb and dLManII. Moreover, the triazoles 6-8 and also the sulfones 9 and 10 (Scheme 1) were assayed toward commercial enzymes, Canavalia ensiformis (jack bean) α-mannosidase (JBMan) (EC 3.2.1.24, GH family 38) and Aspergillus saitoi α-1,2-mannosidase (AspMan) (EC 3.2.1.113, GH family 47), to investigate their selectivity and inhibitory activity towards mannoside-processing glycosidases. Based on high sequence similarities between the active sites of human endoplasmic reticulum α-mannosidase I (hERManI) and AspMan34, the latter was used as a model enzyme for mammalian endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi α-mannosidases from the GH family 47.35-37

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions. (a) 2a, 2b or 2c, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, DMF:H2O 3:1, 3 h, rt, 86-91%; (b) K2CO3, MeOH, 30 min, rt, 87-93%.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The synthetic route to the target conjugates 6-8 is depicted in Scheme 1. The d-mannose azido building block 1 was prepared by SnCl4-catalyzed reaction of peracetylated mannose with TMSN3 in almost quantitative yield.23,38

The application of the same procedure as reported in our previous paper,8 i.e. coupling of 1 with alkynes 2a-2c at rt in DMF:H2O (3:1) solvent mixture using copper (II) sulfate and sodium ascorbate, provided the 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles 3,39 4 and 5 in high yield. Subsequent removal of acetyl groups with K2CO3 in MeOH afforded the target conjugates 6,39 7 and 8, respectively. Their structures were identified by the presence of an olefinic proton signal belonging to the 1,2,3-triazole moiety, which appeared as a singlet at δ 8.50-7.77 in the 1H NMR spectrum. This simple reaction sequence provided glycoside mimetics suitable for screening their selectivity and potency towards various α-mannosidases.

2.2. Biochemical evaluation and molecular modelling

In order to test the inhibitory activity of the synthesized mannosides, a simple chromogenic assay using p-nitrophenyl α-d-mannoside was used with GH family 38 mannosidases. However, as the GH family 47 enzyme (AspMan) does not accept arylmannosides, a normal phase HPLC-based assay with a mannotetrasaccharide as the substrate had to be developed (see Supplement). While sulfone derivatives 9-10 inhibited only the α-mannosidases from the GH family 38 (dGMIIb, dLManII, JBMan) at the mM level, the triazole conjugates 6-8 showed opposite inhibitory activities (Table 1). They were more potent and selective towards the α-mannosidase from the GH family 47 [IC50(AspMan) = 50-250 μM] and weaker inhibitors of the α-mannosidases from the GH family 38 [IC50(dGMIIb, dLManII, JBMan) = 0.4-6 mM]. Within the GH family 38, all triazole derivatives were more selective towards the plant α-mannosidase [IC50(JBMan) = 0.4-1.1 mM] in comparison with the animal Golgi and lysosomal α-mannosidases [IC50(dGMIIb, dLManII) = 0.5-6 mM].

Table 1.

Measured IC50 values for class I (AspMan) and class II (dGMIIb, dLManII and JBMan) α-mannosidases (in mM).

| Compound | dGMIIb | dLManII | JBMan | AspMan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swainsonine | 5.0 × 10−6 | 11.0 × 10−6 | 2.0 × 10−4 | > 10a |

| 1-5 × 10−4 i | ||||

| Mannostatin A | 1.5 × 10−4 | 3.0 × 10−3 | 2.4 × 10−4 j | |

| Kifunensine | 5.2c | 0.12 d | 2 × 10−4 a | |

| 2-5 × 10−5 b | ||||

| α-d-mannosee | n.i.f | n.i.f | ||

| 6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.4 | 0.05 |

| 7 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 6.0 | 5 | 0.4 | 0.25 |

| 9 | 2.0g | n.ig | 2.0 | n.i.h |

| 10 | 1.5g | 1.0g | 1.9 | n.i.h |

Ki value measured for hERMI by Vallée et al.36;

IC50 value measured for AspMan by Elbein et al.40;

Ki value measured for dGMII by Shah et al.41;

IC50 value measured by Kayakiri et al.42;

a mixture of α/β ≈ 95:5;

n.i. - no inhibition or inhibition < 10 % at 5 mM;

IC50 values measured by Poláková et al.30;

n.i. - no inhibition or inhibition < 10 % at 1 mM;

IC50 value measured by Kang et al.43;

IC50 value measured by Ogawa et al.44

To better understand the selective binding and inhibitory activities of the triazole conjugates towards the mannosidases from both GH families 38 and 47, 3-D models of the inhibitor-enzyme complexes were built by molecular docking techniques. The compounds 6-8 were docked into dGMII (PDB ID: 3BLB),45 bLM (PDB ID: 1O7D)46 and ERManI (PDB ID: 1FO3)47 which represent enzyme models for the dGMIIb, dLManII and AspMan, respectively, used in this paper. We also built 3-D complexes of sulfone derivatives 9-10 with dGMII, bLM and ERManI with the aim to compare the influence of the triazole and sulfone functional groups for binding of the inhibitors to the α-mannosidases.

The triazoles 6-8, which showed the best binding properties towards AspMan, have similar binding modes with ERManI (Figure 1A). Their mannose moiety was bound at the bottom of the ERManI active site, interacting with Ca2+ ion, Glu663, Glu689, Glu599, Phe659, Arg597 and a water molecule (Figure 1B). The binding poses of the mannose moiety of 6-8 were identical with that found in a crystal structure of hERManI with a thiodisaccharide substrate analogue.37 Due to the different lengths of the arylalkyl triazole linkers of the inhibitors, apparent differences in the binding modes of these structural moieties were found. The triazole ring of the best inhibitor 6 is oriented with its polar N=N moiety to Arg597 and Leu525 to favour interactions with the enzyme (Figure 1B). These interactions were also found in the crystal structure of nanomolar inhibitor kifunensine (IC50 = 200 nM) with ERManI (PDB ID: 1FO3).36 The triazoles 7-8 with weaker inhibitory activities have a different binding mode of the triazole ring (see a superposition of the docked structures in Figure 1A), which disfavours the interactions with Arg597 and Leu525. The different accommodation of the triazole ring of these inhibitors caused distinct positioning of their benzene moiety in comparison with 6. The aromatic rings of all inhibitors were placed in a pocket that consisted of polar (Glu396, Thr394, Arg461) as well as hydrophobic amino acid residues (Ala460, Phe329). Elongation of the aromatic linker (phenyl<phenylmethyl<phenylethyl) in 6-8 was accompanied with a decrease of the inhibitory activity (50 μM > 100 μM > 250 μM, Table 1). This is explained by less preferred interactions of the aryltriazole moieties of 7 and 8 with Arg597, Leu525, Ala460 and Arg461 as compared with our most potent inhibitor 6. The importance of the triazole ring for inhibitory activities of 6-8 was further supported by the additional biological assays of structurally analogous sulfone derivatives 9-10. The compounds with the sulfone moiety did not show any significant inhibition of AspMan (IC50 > 1 mM).

Figure 1.

(A) A superposition of the compounds 6 (with carbons in green), 7 (in yellow) and 8 (in magenta) docked in the active site of hERManI (PDB ID: 1FO3)36; (B) Selected interactions between the inhibitor 6 (in red) and hERManI.

As discussed above, the triazole and sulfone derivatives exhibited opposite inhibitory activities towards the α-mannosidases from the GH families 38 and 47. Taking into account our previous results30, it indicates that the replacement of the sulfone function by the triazole ring did not significantly alter the potency and selectivity of the inhibitors towards the α-mannosidases from the GH family 38. By a superposition of the docked triazole derivative 7 with sulfone 9, both having benzyl function at the active site of dGMII (Figure 2), decreasing inhibitory activities of the triazole derivatives 6-8 may be explained by less favoured interactions of the triazole ring with Asp341, Tyr269 and Arg228. The distinct positioning of the triazole ring also induced a different binding of the aromatic moiety of the inhibitor compared with the sulfone analogue.

Figure 2.

A superposition of the compound 7 with an analogous mannoside 9 with the triazole group substituted by the sulfone group in the active site of dGMII (PDB ID: 3BLB).45 For a comparison, interactions of triazole and sulfone group with active-site amino acid residues of dGMII (Asp341, Tyr269 and Arg228) are visualized.

Additional docking of the triazole 7 into both dGMII and bLM may explain why no selective binding of 6-8 was observed. The five best docking poses of 7 in dGMII is compared with docking poses in bLM (Fig. 3.). The aryl triazole moiety of 7 binds to hydrophobic regions (the sites B1 and B2 in Figure 3) which are chemically similar in both enzymes. In contrast, the site B3, which consists of a negatively charged acidic dyad Asp270-Asp340 in dGMII and polar neutral dyad Asn262-Ser318 in bLM, and which could be responsible for selective interactions with the inhibitors, is occupied by neither of the docked compounds.

Figure 3.

The best five docking poses for the triazole 7 found for dGMII and bLM. In both cases the benzyl moiety of the inhibitor was found in two binding sites (B1 and B2). A binding site (B3) which may be responsible for a selective binding of the inhibitor was empty. This may explain the lack of selectivity observed for the triazole mannosides.

3. Conclusion

Three triazole conjugates derived from D-mannose showed inhibitory activities against the α-mannosidase from the GH 47 at the micromolar level, while their sulfone analogues were inactive. The triazole conjugate 6 was the most potent inhibitor of the enzyme from the GH family 47 [IC50(AspMan) = 50 μM]; its selectivity is demonstrated by the IC50 ratio of 100 as compared to GH family 38 members. The results from the molecular modelling imply that the interactions of the polar N=N moiety of the inhibitor triazole ring with Arg597 and Leu525 of the enzyme (hERManI) are probably important for binding affinities of triazole conjugates.

The triazole conjugates were weak milimolar inhibitors of animal and plant α-mannosidases from the GH family 38. Thus, the D-mannose triazole structural moiety seems to be inappropriate building block for inhibitors of the α-mannosidases from the GH family 38. On the other hand, the sulfones only inhibited members of this family, although with rather high IC50 values. Thus, further refinements of their structures are required to explore their potential as effective mannosidase inhibitors; furthermore, the inhibitory activity of the triazoles in cell culture assays should be tested to examine the potential of these compounds as inhibitors of N-glycan processing in vivo.

4. Experimental

4.1. General methods

TLC was performed on aluminium sheets precoated with silica gel 60 F254 (Merck). Flash column chromatography was carried out on silica gel 60 (0.040-0.060 mm, Merck) with distilled solvents (hexane, ethylacetate, acetonitrile, methanol). Dichloromethane was dried (CaH2) and distilled before use. All reactions containing sensitive reagents were carried out under an argon atmosphere. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C with a VNMRS 400 MHz Varian spectrometer, chemical shifts are referenced to either TMS (δ 0.00, CDCl3 for 1H) or HOD (δ 4.87, CD3OD for 1H), and to internal CDCl3 (δ 77.23) or CD3OD (δ 49.15) for 13C. Optical rotations were measured on a Jasco P2000 polarimeter at 20 °C. High resolution mass determination was performed by ESI-MS on a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Exactive instrument operating in positive mode. Inhibition assays for GH family 38 enzymes were performed using a microplate reader (Epoch, BioTek and Gen5TM data collection and analysis software), whereas a Shimadzu HPLC system (equipped with an SIL-30AC injector, LC-30AD pump and a RF-20AXS fluorescence detector) was used for the assays of the GH family 47 enzyme.

The conjugates 6-8 used in biological tests were lyophilized before the use. p-Nitrophenyl α-d-mannopyranoside (pNP-Manp), jack bean α-mannosidase and alkynes 2a-c were purchased from Sigma; Aspergillus saitoi α1,2-mannosidase was purchased from Prozyme and swainsonine and mannostatin A from Calbiochem. A mixture of manno-tetrasaccharides (supplied by Dr. Machová; 500 μg) was subject to pyridylamination in order to introduce a fluorescent tag and the major tetrasaccharide (Manα1,2-Manα1,2-Manα1,2-Man-PA) was purified by reversed phase HPLC (Hyperclone 5μ ODS C18, 250 × 4 mm; Phenomenex) followed by normal phase HPLC (TSKgel Amide-80, 250 × 4.6 mm; Tosoh) analogous to previously published procedures;48 the peaks containing the fluorescent tetrasaccharide were verified by MALDI-TOF MS and up to two mannose residues could be released from the substrate upon incubation with Aspergillus saitoi α1,2-mannosidase (the innermost α1,2-linkage is resistant due to reduction of the reducing terminus during pyridylamination).

4.2. Chemistry

4.2.1. Synthesis of conjugates (3-5)

To a solution of azide 1 (0.1 g, 0.268 mmol) in DMF: H2O (1.6 mL, 3:1) alkyne 2a-c (1.1 eq) was added followed by sodium ascorbate (0.042 g, 0.214 mmol) and Cu(II) sulphate (0.017 g, 0.107 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for about 3 h. The reaction mixture was poured into satd. NH4Cl (150 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 25 mL). The organic extracts were combined, washed with water, dried and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane:EtOAc 5:2→1:1).

4.2.1.1. 1-(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-mannopyranosyl)-4-phenyl-1,2,3-triazole (3)

Colourless oil (0.11 g, 90%). [α]d = +58 (c 0.5, CHCl3). lit39 [α]d = + 65.5 (c = 1.01, CHCl3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.98 (s, 1H, CHN), 7.87-7.83 (m, 2H, C6H5), 7.47-7.35 (m, 3H, C6H5), 6.08 (d, 1H, J1,2 2.7 Hz, H-1), 6.02 (dd, 1H, J2,3 3.8 Hz, H-2), 5.98 (dd, 1H, J3,4 8.8 Hz, H-3), 5.40 (t, J4,5 9.0 Hz, H-4), 4.40 (dd, J5,6b 5.4 Hz, J6a,6b 12.5 Hz, H-6b), 4.08 (dd, J5,6a 2.7 Hz, H-6a), 3.96 (ddd, H-5), 2.09, 2.07, 2.06, 2.04 (each s, each 3H, 4× CH3CO); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.6, 169.8, 169.7, 169.4 (4× CH3CO), 148.4 (NC=CH), 129.8, 129.0, 128.7, 126.0, 119.9 (C6H5, NC=CH), 83.7 (C-1), 72.3 (C-5), 68.9, 68.4 (C-2, C-3), 66.2 (C-4), 61.7 (C-6), 20.8, 20.7 (2×), 20.6 (4× CH3CO). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C22H25N3O9]H+: 476.16636. Found: 476.16676.

4.2.1.2. 4-Benzyl-1-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-mannopyranosyl)-1,2,3-triazole (4)

Colourless oil (0.11 g, 86%). [α]d = +30 (c 0.5, CHCl3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.35-7.22 (m, 6H, CHN, C6H5), 5.96-5.91 (m, 3H, H-1, H-2, H-3), 5.35 (m, 1H, H-4), 4.33 (dd, J5,6b 5.5 Hz, J6a,6b 12.5 Hz, H-6b), 4.12 (m, 2H, PhCH2), 4.04 (dd, J5,6a 2.6 Hz, H-6a), 3.86 (ddd, H-5), 2.06, 2.04 (2×), 2.03 (each s, each 3H, 4× CH3CO); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.5, 169.8 (2×), 169.4 (4× CH3CO), 148.6 (NC=CH), 138.5, 128.8, 126.8, 121.9 (C6H5, NC=CH), 83.6 (C-1), 72.1 (C-5), 68.9, 68.4 (C-2, C-3), 66.2 (C-4), 61.7 (C-6), 32.22 (PhCH2), 20.8 (2×), 20.7, 20.6 (4× CH3CO). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C23H27N3O9]H+: 490.18201. Found: 490.18225.

4.2.1.3. 1-(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-mannopyranosyl)-4-(2-phenylethyl)-1,2,3-triazole (5)

Colourless oil (0.12 g, 91%). [α]d = +28 (c 0.5, CHCl3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.30-7.17 (m, 6H, CHN, Ph), 5.96 (d, 1H, J1,2 2.6 Hz, J2,3 3.7 Hz, H-2), 5.92-5.89 (m, 2H, H-1, H-3), 5.36 (t, 1H, J3,4 9.1 Hz, H-4), 4.34 (dd, J5,6b 5.2 Hz, J6a,6b 12.5 Hz, H-6b), 4.02 (dd, J5,6a 2.6 Hz, H-6a), 3.76 (ddd, H-5), 3.11-3.00 (m, 4H, Ph(CH2)2), 2.08, 2.06, 2.05, 2.04 (each s, each 3H, 4× CH3CO); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.6, 169.8, 169.7, 169.4 (4× CH3CO), 148.0 (NC=CH), 141.0, 128.6, 128.5, 126.3, 121.3 (C6H5, NC=CH), 83.6 (C-1), 71.9 (C-5), 68.9, 68.5 (C-2, C-3), 66.2 (C-4), 61.6 (C-6), 35.4, 27.4 (Ph(CH2)2), 20.9, 20.8 (2×), 20.7 (4× CH3CO). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C24H29N3O9]H+: 504.19766. Found: 504.19788.

4.2.2. Removal of acetyl protective groups. Synthesis of conjugates (6-8)

Compound 3, 4 or 5 (0.2 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (3 mL) and K2CO3 (0.5 eq) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt until disappearance of starting material (30 min), then filtered and concentrated. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (CH3CN:MeOH 15:1). Evaporation and lyophilisation gave the target compound 6, 7 or 8.

4.2.2.1. 1-α-d-mannopyranosyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3-triazole (6)

White powder (57.2 mg, 93%). [α]d = +82 (c 0.9, MeOH); lit39 [α]d = + 98.0 (c = 1.34, MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 8.50 (s, 1H, CHN), 7.85-7.81 (m, 2H, C6H5), 7.46-7.33 (m, 3H, C6H5), 6.08 (d, 1H, J1,2 2.7 Hz, H-1), 4.76 (dd, 1H, J2,3 3.5 Hz, H-2), 4.12 (dd, 1H, J3,4 8.5 Hz, H-3), 3.86 (dd, J5,6a 2.7 Hz, J6a,6b 12.5 Hz, H-6a), 3.81-3.76 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6b), 3.40 (ddd, J5,6b 6.5 Hz, H-5); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 149.0 (NC=CH), 131.4, 130.0, 129.5, 126.8 (C6H5), 122.1 (NC=CH), 88.5 (C-1), 78.7 (C-5), 72.6 (C-3), 70.1 (C-2), 68.7 (C-4), 62.6 (C-6). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C14H17N3O5]H+: 308.12410. Found: 308.12421.

4.2.2.2. 4-Benzyl-1-α-d-mannopyranosyl-1,2,3-triazole (7)

White powder (57.2 mg, 89%). [α]d = +63 (c 0.6, MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.82 (s, 1H, CHN), 7.42-7.13 (m, 5H, C6H5), 5.90 (d, 1H, J1,2 2.7 Hz, H-1), 4.62 (dd, 1H, J2,3 3.5 Hz, H-2), 4.03-4.00 (m, 3H, H-3, PhCH2), 3.76 (dd, J5,6a 2.7 Hz, J6a,6b 12.5 Hz, H-6a), 3.73-3.65 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6b), 3.25 (m, 1H, H-5); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 148.7 (NC=CH), 140.2, 129.6, 127.5 (C6H5), 123.7 (NC=CH), 88.2 (C-1), 78.5 (C-5), 72.5 (C-3), 70.0 (C-2), 68.6 (C-4), 62.5 (C-6), 32.5 (PhCH2). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C15H19N3O5]H+: 322.13975. Found: 322.13983.

4.2.2.3. 1-α-d-mannopyranosyl-4-(2-phenylethyl)-1,2,3-triazole (8)

White powder (58.3 mg, 87%). [α]d = +59 (c 0.6, MeOH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.77 (s, 1H, CHN), 7.26-7.13 (m, 5H, C6H5), 5.94 (d, 1H, J1,2 2.5 Hz, H-1), 4.68 (dd, 1H, J2,3 3.5 Hz, H-2), 4.03 (dd, 1H, J3,4 8.7 Hz, H-3), 3.80-3.71 (m, H-4, H-6a, H-6b), 3.21 (ddd, 1H, J4,5 8.8 Hz, J5,6a 2.8 Hz, J5,6b 5.8 Hz, H-5), 3.01-2.97 (m, 4H, Ph(CH2)2); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 148.5 (NC=CH), 142.2, 129.5, 129.4, 127.1 (C6H5), 123.3 (NC=CH), 88.3 (C-1), 78.2 (C-5), 72.5 (C-3), 70.1 (C-2), 68.4 (C-4), 62.5 (C-6), 36.5, 28.3 (Ph(CH2)2). HRMS (ESI-MS): m/z: calcd for [C16H21N3O5]H+: 336.15540. Found: 336.15558.

4.3. Biochemistry

4.3.1. Enzyme preparation

The purification and characterization of recombinant Drosophila melanogaster Golgi (dGMIIb) and lysosomal (dLManII) mannosidases was carried out as we described recently.27

4.3.2. Class II α-Mannosidase assay30

The supernatants of yeast expressing soluble forms of the α-mannosidase were incubated with the substrate PNP-Manp at 37 °C for 2-3 h. The standard assay mixture consisted of 50mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5 for JBMan, pH 5.2 for LManII or pH 5.8 for GMIIb), 2mM pNP-Manp (from 100mM stock solution in DMSO), 1-5 μl enzyme (supernatant of the culture medium) and in case of GMIIb final 0.2mM CoCl2 in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. A blank sample contained no enzyme. The samples were prepared in triplicates. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 0.5 ml of 100 mM Na2CO3 and the absorbance was recorded at 410 nm (spectrophotometer).

4.3.2.1. Inhibition assays30

Inhibition assays of mannose conjugates 6-8 with dLManII and dGMIIb were carried out in the conditions outlined above and the IC50 values were determined. Stock concentrations of inhibitors were made up in DMSO to a concentration of 100 mM and stored at −20°C. The inhibitory effect of DMSO was tested for both enzymes. The 5% DMSO was selected as a maximal final concentration in the assay. This concentration causes 10% or 15% of inhibition of LM or GMIIb, eventually. For this reason maximal concentration of the tested compounds in the reaction was 5 mM and data were obtained in triplicate. The inhibitory effect of the compounds were calculated by percentage of inhibition toward a control sample containing the same concentration of DMSO. Swainsonine and mannostatin A were used as standard mannose inhibitors.

Inhibition of jack bean α-mannosidase activity was performed in microtiter plates in a final volume of 50 μl according to a published protocol.27,49 The tested compounds 6-10 were prepared as stock solutions in DMSO (100 mM) and data were obtained in triplicate over a concentration range of 1-5 mM. 5 μl of jack bean α-mannosidase was pre-incubated for 5 min at 20 °C with the inhibitor under evaluation. The reaction mixture contained 80 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) and 5 mM pNP-Manp. The absorbance of the reaction was measured at 405 nm using microplate reader.

4.3.3. Class I α-Mannosidase assay

As pNP-Manp is not a substrate for GH family 47 enzymes, an HPLC-based assay was developed using a fluorescently-labelled tetrasaccharide (for its preparation, see above). Approximately 1 μg of manno-tetrasaccharide was incubated with 0.2 μl (4 μU) Aspergillus saitoi α1,2-mannosidase in the absence or presence of 0.01, 0.1 or 1.0 mM inhibitor; all assays were performed at pH 5 (40 mM ammonium acetate) in a volume of 10 μl and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Normal phase HPLC was then performed using a Shimadzu HPLC system (see above) to separate the smaller product from the substrate using a Tosoh Amide 80 column; solvent A was 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 7, and solvent B was 95% (v/v) acetonitrile/water. A gradient (1 ml/min) from 75% solvent B down to 65% was applied over 10 minutes, before holding 65% solvent B for 5 minutes and finally returning to the starting conditions. The conversion of substrate to product was determined by integration of the peak areas (fluorescence with excitation and emission at respectively 320 and 400 nm).

4.4. Molecular Modelling

The crystal structures of dGMII (PDB ID: 3BLB),45 bLM (PDB ID: 1O7D)46 and hERManI (PDB ID: 1FO3)47 were used as 3-D enzyme models of hGMII, hLM and AspMan for docking of synthesized mannosides with the GLIDE program50,51 of the Schrödinger package.52 Protonation states of amino acid residues of enzymes were calculated for the pH = 6.0 ± 1 (dGMII), 4.5 ± 1 (bLM) and 7.0 ± 1 (hERManI) by the Protein Preparation Wizard53 of the Schrödinger package. For docking with dGMII all molecules of water at the active site of dGMII were deleted except one (WAT1820, numbering according to PDB ID: 3BLB). This water has been shown to be conserved in crystal structures of dGMII either with intact substrates and inhibitors.31,32,45,54 For docking with hERManI all except of 8 molecules of water at the active site were deleted (WAT705, 708, 709, 710, 711, 713, 803 and 925, numbering according to PDB ID: 1FO3). In all docking calculations the catalytic acid (Asp341 in dGM and Asp319 in the case of (bLM) was modelled in the protonated form in accordance with its catalytic role as a general acid. The mannoside ligands were docked into the active site in the reactive skew boat B2,5 conformation of the mannose ring and in 3S1 one in the case of hERManI. The receptor box for the docking conformational search was centred at the Zn2+ ion co-factor (for (dGMII and bLM) and Ca2+ ion (hERManI) bound at the bottom of the active site with a size of 39×39×39 Å using partial atomic charges for the receptor from the OPLS2005 force field except for the Zn2+ and side chains of His90, Asp92, Asp204, Arg228, Tyr269, Asp341 and His471 (analogous residues were selected for bLM). For these structural fragments the charges were calculated at the quantum mechanics level with the DFT (Density Functional Theory) method (M06-2X)55,56 using hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) model (M06-2X/LACVP**:OPLS2005) with the QSite program57 of the Schrödinger package. For hERManI an analogous approach was used for the atomic charges calculations (Ca2+ ion, water molecules, side chains of Asn327, Glu570 and Glu663, sequences Glu397-Thr394, Gly459-Ser464, Phe329-Glu330, Ile333-Arg334, Thr688-Glu689, Arg597-Glu599 and Leu525 were treated in the QM part of the QM/MM calculations). The grid maps were created with no Van der Waals radius and charge scaling for the atoms of the receptor. Flexible docking in standard (SP) precision was used. The partial charges of the ligands were calculated at the DFT level (M06-2X/LACVP**). The potential for nonpolar parts of the ligands was softened by scaling the Van der Waals radii by a factor of 1.0 for atoms of the ligands with partial atomic charges less than specified cut-off of 0.15. The 5000 poses were kept per ligand for the initial docking stage with scoring window of 100 kcal mol−1 for keeping initial poses; the best 400 poses were kept per ligand for energy minimization. The ligand poses with RMS deviations less than 0.5 Å and maximum atomic displacement less than 1.3 Å were discarded as duplicates. The post-docking minimization for 10 ligand poses with the best docking score was performed and optimized structures were saved for subsequent analyses using the MAESTRO58 viewer of the Schrödinger package.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency (the project APVV-0484-12), Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of Slovak Republic and Slovak Academy of Sciences (the project VEGA-2/0159/12), the Slovak State Programme Project No. 2003SP200280203 and the Research & Development Operational Programmes funded by the ERDF (Centre of Excellence on Green Chemistry Methods and Processes, CEGreenI, Contract No. 26240120001, and Amplification of the Centre of Excellence on Green Chemistry Methods and Processes, CEGreenII, Contract No. 26240120025) as well as by the Austria Science Fund (FWF, grant P23607 to IBHW).

Abbreviations

- GMII

Golgi α-mannosidase II

- hGMII

human Golgi α-mannosidase II

- dGMII

Drosophila melanogaster α-mannosidase II

- dGMIIb

catalytic domain of Drosophila melanogaster Co(II)-activated Golgi α-mannosidase IIb, recombinant enzyme homolog of human Golgi α-mannosidase II

- LM

lysosomal α-mannosidase

- hLM

human lysosomal α-mannosidase

- bLM

Bos taurus lysosomal α-mannosidase

- dLManII

catalytic domain of Drosophila melanogaster lysosomal α-mannosidase II, recombinant enzyme homolog of human lysosomal α-mannosidase

- JBMan

jack bean α-mannosidase (Canavalia ensiformis)

- AspMan

Aspergillus saitoi α1,2-mannosidase

- hERManI

human endoplasmic reticulum α-mannosidase I

Footnotes

Supplementary data. 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the compounds 6-8 and examples of HPLC data. Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version

References

- 1.Tornoe CW, Meldal M. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952–3015. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolb HC, Sharpless KB. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses JE, Moorhouse AD. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1249–1262. doi: 10.1039/b613014n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutz JF, Zarafshani Z. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2008;60:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baskin JM, Bertozzi CR. Qsar Comb. Sci. 2007;26:1211–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tron GC, Pirali T, Billington RA, Canonico PL, Sorba G, Genazzani AA. Med. Res. Rev. 2008;28:278–308. doi: 10.1002/med.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agalave SG, Maujan SR, Pore VS. Chem-Asian J. 2011;6:2696–2718. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poláková M, Beláňová M, Mikušová K, Lattová E, Perreault H. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:289–298. doi: 10.1021/bc100421g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marra A, Staderini S, Berthet N, Dumy P, Renaudet O, Dondoni A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013:1144–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jogula S, Dasari B, Khatravath M, Chandrasekar G, Kitambi SS, Arya P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013;2013:5036–5040. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee C, Makinen K, Savolainen J, Leino R. Chem-Eur. J. 2013;19:7961–7974. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang GN, Andre S, Gabius HJ, Murphy PV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:6893–6907. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25870f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu TL, Hanson SR, Kishikawa K, Wang SK, Sawa M, Wong CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2614–2619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson BL, Bornaghi LF, Poulsen SA, Houston TA. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8115–8125. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giguere D, Patnam R, Bellefleur MA, St-Pierre C, Sato S. Roy, R. Chem. Commun. 2006:2379–2381. doi: 10.1039/b517529a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tejler J, Skogman F, Leffler H, Nilsson UJ. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:1869–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bokor E, Docsa T, Gergely P, Somsak L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmon AJ, Williams ML, Maresca A, Supuran CT, Poulsen SA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:6058–6061. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson BL, Innocenti A, Vullo D, Supuran CT, Poulsen SA. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:1945–1953. doi: 10.1021/jm701426t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li TH, Guo LN, Zhang Y, Wang JJ, Li ZH, Lin L, Zhang ZX, Li L, Lin JP, Zhao W, Li J, Wang PG. Carbohydr. Res. 2011;346:1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson BL, Long H, Sim E, Fairbanks AJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:6265–6267. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang JJ, Garrossian M, Gardner D, Garrossian A, Chang YT, Kim YK, Chang CWT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hradilová L, Poláková M, Dvoráková B, Hajdúch M, Petruš L. Carbohydr. Res. 2012;361:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azcune I, Balentova E, Sagartzazu-Aizpurua M, Santos JI, Miranda JI, Fratila RM, Aizpurua JM. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013:2434–2444. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossi LL, Basu A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:3596–3599. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dedola S, Hughes DL, Nepogodiev SA, Rejzek M, Field RA. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemčovičová I, Šesták S, Rendic D, Plšková M, Mucha J, Wilson IBH. Glycoconjugate J. 2013;30:899–909. doi: 10.1007/s10719-013-9495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winchester B. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1984;12:522–524. doi: 10.1042/bst0120522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goss PE, Baker MA, Carver JP, Dennis JW. Clin. Cancer. Res. 1995;1:935–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poláková M, Šesták S, Lattová E, Petruš L, Mucha J, Tvaroška I, Kóňa J. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah N, Kuntz DA, Rose DR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9570–9575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong W, Kuntz DA, Ernber B, Singh H, Moremen KW, Rose DR, Boons GJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8975–8983. doi: 10.1021/ja711248y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rose DR. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 2012;22:558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue T, Yoshida T, Ichishima E. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995;1253:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tempel W, Karaveg K, Liu ZJ, Rose J, Wang BC, Moremen KW. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29774–29786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallee F, Karaveg K, Herscovics A, Moremen KW, Howell PL. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41287–41298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karaveg K, Siriwardena A, Tempel W, Liu ZJ, Glushka J, Wang BC, Moremen KW. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16197–16207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Percec V, Leowanawat P, Sun HJ, Kulikov O, Nusbaum CD, Tran TM, Bertin A, Wilson DA, Peterca M, Zhang SD, Kamat NP, Vargo K, Moock D, Johnston ED, Hammer DA, Pochan DJ, Chen YC, Chabre YM, Shiao TC, Bergeron-Brlek M, Andre S, Roy R, Gabius HJ, Heiney PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9055–9077. doi: 10.1021/ja403323y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwardt O, Rabbani S, Hartmann M, Abgottspon D, Wittwer M, Kleeb S, Zalewski A, Smiesko M, Cutting B, Ernst B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:6454–6473. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbein AD, Tropea JE, Mitchell M, Kaushal GP. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:15599–15605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah N, Kuntz DA, Rose DR. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13812–13816. doi: 10.1021/bi034742r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayakiri H, Takase S, Shibata T, Okamoto M, Terano H, Hashimoto M, Tada T, Koda S. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:4015–4016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang MS, Elbein AD. Plant Physiol. 1983;71:551–554. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogawa S, Morikawa T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000:1759–1765. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuntz DA, Nakayama S, Shea K, Hori H, Uto Y, Nagasawa H, Rose DR. Chembiochem. 2010;11:673–680. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heikinheimo P, Helland R, Leiros HKS, Leiros I, Karlsen S, Evjen G, Ravelli R, Schoehn G, Ruigrok R, Tollersrud OK, McSweeney S, Hough E. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:631–644. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vallee F, Yip P, Lipari F, Sleno B, Romero P, Karaveg K, Moremen K, Herscovics A, Howell PL. Glycobiology. 2000;10:1141–1141. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paschinger K, Hykollari A, Razzazi-Fazeli E, Greenwell P, Leitsch D, Walochnik J, Wilson IBH. Glycobiology. 2012;22:300–313. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuntz DA, Ghavami A, Johnston BD, Pinto BM, Rose DR. Tetrahedron:Asymmetry. 2005;16:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, Mainz DT. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glide, version 5.7. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrödinger Suite 2011 Protein Preparation Wizard; Epik version 2.2. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]; Impact version 5.7. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]; Prime version 3.0. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuntz DA, Zhong W, Guo J, Rose DR, Boons GJ. Chembiochem. 2009;10:268–277. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008;120:215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y, Truhlar DG. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:157–167. doi: 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qsite, version 5.7. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maestro, version 9.2. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.