Abstract

Endothelin-1 (EDN1) influences both craniofacial and cardiovascular development and a number of adult physiological conditions by binding to one or both of the known endothelin receptors, thus initiating multiple signaling cascades. Animal models containing both conventional and conditional loss of the Edn1 gene have been used to dissect EDN1 function in both embryos and adults. However, while transgenic Edn1 over-expression or targeted genomic insertion of Edn1 has been performed to understand how elevated levels of Edn1 result in or exacerbate disease states, an animal model in which Edn1 over-expression can be achieved in a spatiotemporal-specific manner has not been reported. Here we describe the creation of Edn1 conditional over-expression transgenic mouse lines in which the chicken β-actin promoter and an Edn1 cDNA are separated by a strong stop sequence flanked by loxP sites. In the presence of Cre, the stop cassette is removed, leading to Edn1 expression. Using the Wnt1-Cre strain, in which Cre expression is targeted to the Wnt1-expressing domain of the central nervous system (CNS) from which neural crest cells (NCCs) arise, we show that stable CBA-Edn1 transgenic lines with varying EDN1 protein levels develop defects in NCC-derived tissues of the face, though the severity differs between lines. We also show that Edn1 expression can be achieved in other embryonic tissues utilizing other Cre strains, with this expression also resulting in developmental defects. CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice will be useful in investigating diverse aspects of EDN1-mediated-development and disease, including understanding how NCCs achieve and maintain a positional and functional identity and how aberrant EDN1 levels can lead to multiple physiological changes and diseases.

Keywords: neural crest cell, hypertension, craniofacial, endothelin-A receptor, craniofacial

Introduction

Endothelin-1 (EDN1) is a 21 amino acid (aa) peptide that has a variety of functions in both embryos and adults. Of the three endothelin ligands (EDN1, 2 and 3), EDN1 can bind to either of the two known endothelin receptors, Endothelin-A (EDNRA) and Endothelin-B (EDNRB) (Takayanagi et al., 1991; Yanagisawa, 1994). EDN1 was isolated and characterized based on its potent vasoconstrictive activity (Yanagisawa et al., 1988), where its action on smooth muscle cells results in changes in vascular tone, primarily acting through Ednra. Numerous roles for EDN1 in vascular diseases of the liver, lungs and kidneys have been described, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Dorrington, 1999; Polikepahad et al., 2006), chronic kidney disease (Dhaun et al., 2012; Gagliardini et al., 2011), hypertension (Moorhouse et al., 2013; Speed and Pollock, 2013) and cirrhosis (Moore, 2004). Elevated EDN1 levels have also been implicated in diseases that include Alzheimer’s disease (Palmer et al., 2013), Sickle cell anemia (Morris, 2008), inflammatory bowel disease (Angerio et al., 2005), demylinating diseases (Hammond et al., 2014; Haufschild et al., 2001) and infectious diseases (Freeman et al., 2014). In addition, EDN1 is also implicated in multiple aspects of cancer progression, including epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Bagnato and Rosano, 2007) and in stimulating tumor angiogenesis (Knowles et al., 2005).

While early studies predicted that targeted disruption of Edn1 or Ednra in mice would lead to resistance to hypertension, Edn1−/− (Kurihara et al., 1994) and Ednra−/− (Clouthier et al., 1998) embryos were born with numerous craniofacial and cardiovascular defects due to disruption in cranial and cardiac neural crest cell (NCC) patterning during early embryogenesis. Edn1 is first expressed in the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm of the mandibular portion of the first pharyngeal arch and arches 2–6, transient structures on the ventral embryo surface that give rise to most facial and neck structures (Maemura et al., 1996) (Clouthier et al., 1998; Yanagisawa et al., 1998a; Yanagisawa et al., 1998b). In contrast, Ednra expression is found in all cranial NCCs immediately following emigration of NCCs from the neural tube (Clouthier et al., 1998; Yanagisawa et al., 1998a; Yanagisawa et al., 1998b). From targeted inactivation studies in mice and analysis of mutant and morphant zebrafish, EDN1-mediated EDNRA signaling is now known to establish the identity of NCCs in the mandibular portion of the first pharyngeal arch (Kimmel et al., 2003; Miller and Kimmel, 2001; Miller et al., 2000a; Miller et al., 2007; Nair et al., 2007; Ozeki et al., 2004; Ruest et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2006). In mice, loss of this signaling results in a homeotic transformation of lower jaw structures into more maxillary like structures, including duplication of the maxilla and much of the secondary palate in the lower jaw (Ruest et al., 2004). Similar changes in the maxilla are observed in human Auriculocondylar Syndrome (ACS) patients, in which downstream mediators of EDN1/EDNRA signaling are disrupted (Clouthier et al., 2013; Rieder et al., 2012), illustrating the conserved nature of this pathway in vertebrate facial development. In contrast to these findings, the maxilla of embryos in which an Edn1 cDNA has been inserted into the Ednra locus undergoes transformation into a mandible-like structure (Sato et al., 2008b). This change illustrates that while all cranial NCCs are competent to respond to Ednra signaling, the confinement of signaling is achieved by restricting Edn1 expression to the mandibular arch. However, the ability to induce Edn1 expression in a specific spatio-temporal manner does not exist.

Because of neonatal lethality associated with targeted deletion of either Edn1 or Ednra, experiments designed to better understand the role of Endothelin signaling in adult hypertension and cardiac function have used a conditional loss of function approach (Kedzierski et al., 2003; Shohet et al., 2004). In addition, transgenic mouse strains in which Edn1 expression was driven by its own promoter (Hocher et al., 1997; Shindo et al., 2002) or an endothelial-specific promoter (Amiri et al., 2004) have further illustrated roles for endothelin in endothelial dysfunction (Amiri et al., 2004) hypertension (Leung et al., 2011), renal damage (Hocher et al., 1997; Shindo et al., 2002) and retinal degeneration (Mi et al., 2012). In addition, a role for astrocytic EDN1 in neuropathic pain was demonstrated by transgenic mice in which the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter drove expression of Edn1 (Lo et al., 2005). However, as with the developmental activity of endothelin signaling, none of these approaches have provided the ability to target Edn1 expression in a spatiotemporal manner, thus limiting the utility of these mice in examining how EDN1 functions in human disease.

Here we report the development of an inducible transgenic mouse model in which the expression of Edn1 is regulated by Cre recombinase. We show using the Wnt1-Cre transgenic mouse strain that embryos from four independent lines of transgenic mice have varying elevated levels of EDN1 protein, accompanied by jaw and midfacial defects. These defects are preceded by changes in the expression of genes involved in pharyngeal arch patterning. Because EDN1 can be induced in any tissue at any age by selecting appropriate Cre strains, these mice should prove useful to a variety of scientific fields.

Materials and methods

Transgene construction and animal production

To create an inducible Edn1 transgene, we first used an expression vector (pBALNLXGFP) in which CMV enhancer-chicken β-actin promoter sequences are separated from a multiple cloning cassette by a loxP-neomycin resistance-triple polyA-loxP “stop” cassette (a kind gift of Drs. A Simeone and F. Tuorto, Institute of Genetics and Biophysics, Naples). Due to the presence of restriction enzyme sites within the components of our final transgene, we had to rebuild the expression cassette in a manner that would allow us to excise the final transgene. All cloning was confirmed by restriction digest. We first digested pBALNLXGFP with SalI and ClaI to isolate the CMV enhancer-chicken β-actin promoter sequences. We also digested pBALNLXGFP with ClaI and EcoR1 to isolate the loxP-neor/3xpolyA-loxP cassette (there is an internal SalI site within the latter sequence which prevents isolation of the two sequences together). The isolated sequences were gel purified (Gel Purification Kit, Qiagen). pBluescriptII SK+ was then digested with SalI and ClaI followed by insertion of CMV enhancer-chicken β-actin promoter sequences, creating the plasmid pBA). This plasmid was then cut with ClaI and EcoR1 and the loxP-neor/3xpolyA-loxP cassette inserted. After purification, the resulting plasmid (pBN) was cut with Not I and blunted. To generate a polyA+ sequence for the transgene, the SV40 polyA+ sequence from pCS2+MT (pCS2+ containing a myc-tag sequence) was first cut with NotI, purified and then the ends blunted using Klenow enzyme. After purification, the plasmid was cut with XhoI and the SV40 polyA+ sequence isolated and gel purified. The sequence was then cloned into pSP73 (Promega) cut with XhoI and SmaI. After purification, this plasmid (pSP-PA) was cut with XhoI and SacI, blunted and cloned into the blunted pBN generated above. The resulting plasmid (pBNS) was then digested with SmaI. The plasmid, pmET-1, containing a full length clone of mouse Edn1, was cut with PstI and SmaI, purified, blunted with T7 polymerase and the liberated band then gel purified and cloned into the SmaI-digested pBNS. The resulting plasmid, pBN-Edn1, was verified by both restriction digests and sequencing. The plasmid was cut with KpnI to liberate the transgene from plasmid sequence, with the transgene isolated and purified as previously described (Clouthier et al., 1997). Injection of the transgene was performed as previously described (Clouthier et al., 1997). 22 founder transgenic mice were generated, with 10 used to establish stable lines. Of these, four were chosen for subsequent analysis. The official nomenclature for theses four lines is: B6.129-Tg(ACTB-Edn1)721Clou (MGI:5538246), B6.129-Tg(ACTB-Edn1)1398Clou (MGI:5538247), B6.129-Tg(ACTB-Edn1)1408Clou (MGI:5538248), and B6.129-Tg(ACTB-Edn1)1416Clou (MGI:5538249).

Embryo genotyping

CBA-Edn1 mice and embryos were genotyped by PCR analysis using genomic DNA prepared from tail biopsies or amniotic sacs. Genotyping was performed using the primers 5′-CAG CGC GGT CCT CAG CAA GT -3′ and 5′- ACC TCC CAC ACC TCC CCC TG -3′. Reactions were visualized on a 3% agarose gel. Successful amplification by PCR resulted in a 500 bp band. The Wnt1-Cre (Danielian et al., 1998), Myf5-Cre (Tallquist et al., 2000) and R26R (Soriano, 1999) strains have been previously described. Cre and lacZ genotyping were performed as previously described (Ruest and Clouthier, 2009; Soriano, 1999). The official nomenclature for the Wnt1-Cre, Myf5-Cre and R26R strains is: 129S4.Cg-Tg(Wnt1-cre)2Sor/J, B6.129S4-Myf5tm3(cre)Sor/J) and B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J.

Determination of transgene homozygosity

To determine homozygosity of CBA-Edn1 mice, a quantitative real time PCR assay was performed in which a region corresponding to part of the fifth exon of Edn1 was amplified using the following PCR primers: 5′-GACCATCTGTGTGGCTTCTAC-3′; 5′-GGAACACCTCAGCCTTTCTT-3′. Primer function was verified in a standard PCR reaction, in which they correctly amplified a 92 bp fragment. Primers used to detect the Ramp3 gene (the internal reference gene) have been previously described (Sakurai et al., 2008). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted as described above for genotyping. Amplification was performed using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen). Each PCR reaction contained 80 ng of genomic DNA and 6.25 pmol of each primer. Reactions were carried out on the MyiQ2 machine (BioRad) using the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min. Results were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method, in which the 2−ΔΔCt (fold change) was calculated by subtracting the ΔCt (Ct for Edn1- Ct for Ramp3) of mutant embryos (homozygous and heterozygous) from the ΔCt of wild type embryos.

Skeleton staining

Skeletal staining of E18.5 embryos with alizarin red (bone) and alcian blue (cartilage) was performed as previously described (Ruest et al., 2004). Stained embryos were analyzed and photographed using the Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope fitted with an Olympus DP-11 digital camera. Seven embryos of each genotype were stained and analyzed, with representative embryos from each strain shown in the figures.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

One E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryo from the 1398 and 1416 lines and one E10.5 control embryo were harvested and stored in RNAlater (Qiagen). Total RNA was extracted from whole embryos using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was prepared from total RNA using the QuantiTect cDNA Synthesis Kit (Qiagen). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using 5 ng of cDNA and the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and QuantiTect Primer Assays for Edn1 and Actb (β-actin; Qiagen). RT-PCR and data analysis was performed using a MyiQ2 machine (BioRad). Data analysis was performed using the ΔΔCt method as described previously (Barron et al., 2011).

Whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH)

Whole mount ISH was performed as previously described (Clouthier et al., 1998) with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled antisense cRNA riboprobes against Edn1 (Clouthier et al., 1998), Dlx3 (Clouthier et al., 2000) and Dlx5 (Ruest et al., 2004) on three embryos from each line being examined. One modification was introduced for detection of Edn1 message, with the color development of embryos in (NBT) and (BCIP) performed for two hours on five consecutive days. Overnight washes in TBST in the dark at 4°C were performed between each day of development. This approach was used to increase the signal to noise ratio, a common problem in analyzing Edn1 expression. Embryos were photographed using an Olympus SZX12 microscope as described above.

Enzyme-linked Immunoassay for EDN1 protein levels

Three E12.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from each of the four lines and three E12.5 control embryos were harvested, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Whole embryos were homogenized using a Polytron PT 10–35 (Brinkmann) in 10 ml of 1 M acetic acid containing 0.01 mM pepstatin A for 30 sec. Homogenates were immediately placed in a boiling water bath for 10 min and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. To concentrate EDN1 protein, Sep-Pak Light C18 cartridges (Waters Corp., Milford, Massachusetts) were primed with a sequence of solutions: 4% acetic acid/86% ethanol; absolute methanol; distilled water; 4% acetic acid. Supernatants were thawed on ice and applied to primed cartridges. Protein was eluted with 4% acetic acid/86% ethanol and then lypholized using a centrifugal evaporator (Speed Vac concentrator, Savant). The lyophilized product was resuspended in sample diluent provided by the human Endothelin-1 immunoassay kit (R&D Systems). This kit employs the quantitative enzyme immunoassay (EIA) technique by using an antibody specific for EDN1. Protein concentration was measured by a Bradford assay (Biorad). Equal amounts of protein per sample were then applied to individual wells of the provided EIA 96-well plate alongside standard and control samples provided in the EIA kit. Each plate was then placed in a SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and the optical density of each well determined by taking readings at 450 nm before correcting by subtracting the reading at 620 nm. The data is presented as fold change between mutant and control embryos for each line, with error bars representing standard deviation. Error analysis was performed using an ANOVA model.

Analysis of cellular proliferation and apoptosis

Three E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos each from lines 1398 and 1416 (and three control embryos) were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours on ice and then rinsed through graded ethanols into xylene before paraffin embedding and sectioning along a transverse plane at 7 μm. Detection of proliferating cells was performed using 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation analysis and the Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit (Life Technologies) with Alexa Fluor 594 as the fluorescent label. Detection of apoptosis was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche), with fluorescein as the fluorescent label. Both techniques were performed on the same slide (Barron et al., 2011; Ishii et al., 2005). After both techniques were performed, nuclei were labeled using DAPI. TUNEL, EdU and DAPI fluorescent staining was analyzed on an Olympus BX51 compound microscope fitted with a DP71 digital camera. TUNEL-positive cells (green) were manually counted using ImageJ (NIH) and the cell counter plugin. EdU (red) or DAPI (blue)-labeled cells were automatically counted using ImageJ (NIH) and the analyze particle tool after image threshold adjustment and binary processing. The apoptotic index was calculated by dividing the number of TUNEL-positive cells by the total number of cells (DAPI-positive). The proliferation index was calculated by dividing the number of EdU-positive cells by the total number of cells. Two planes of both maxillary prominences of each embryo were used for cell counting. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Results and Discussion

Creation and analysis CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice

To create a mouse strain in which Edn1 expression could be induced in a specific spatio-temporal pattern in both embryos and adults, we designed a transgene in which the chicken β-actin promoter/enhancer sequence was placed upstream of a mouse Edn1 cDNA (Fig. 1 A). In between these sequences, we inserted a neomycin resistance cassette containing a 3X stop sequence and flanked by loxP sites. Of the 22 founder transgenic mice generated with this construct, 10 were expanded into stable transgenic lines and four were subsequently analyzed in detail (data not shown). All four of these CBA-Edn1 lines produced the expected number of hemizygous pups when crossed with wild type animals (data not shown). Further, homozygous animals from all four lines were achieved at the expected frequency from hemizygous parents and were viable and healthy (data not shown).

Figure 1. Creation of conditional CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice.

A. Design of the CBA-Edn1 conditional transgene. The chicken β-actin (ACTB) promoter is separated from a mouse Edn1 cDNA by a neomycin resistance cassette (neor) flanked by loxP sites. The neor cassette contains a 3X stop sequence, preventing read-through into the Edn1 cDNA. Crossing CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice with mice expressing Cre results in excision of the neor cassette and thus expression of Edn1. B. EDN1 protein levels in E12.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos. CBA-Edn1 animals from all four lines were bred with mice from the Wnt1-Cre strain. Resulting CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos were collected at E12.5 and the level of mature EDN1 for each line measured using an enzyme-linked assay (EIA) (n=3 embryos for each line). The amount of EDN1 is presented as fold-increase over EDN1 levels in control embryos. Error bars represent standard error.

To begin characterization of each line, we examined embryos following tissue-specific activation of the CBA-Edn1 transgene in NCCs. This was accomplished by crossing CBA-Edn1 animals from all four of our lines with mice from the Wnt1-Cre strain (Danielian et al., 1998). Cre expression in this strain occurs in a Wnt1 -expressing cell population within the central nervous system (CNS) from which NCCs arise (Echelard et al., 1994), making it an ideal strain in which to delete genes involved in cranial NCC patterning and development (Chai et al., 2000; Ruest and Clouthier, 2009). CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos were first collected at embryonic day (E) 12.5 and the amount of the mature 21 amino acid form of EDN1 measured using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA). Whole embryo extract was used, as this has been previously shown to be a reliable indicator of EDN protein levels (Clouthier et al., 1998) and allowed us to not pool embryos. We found that embryos from Line 1398 had a 2.64-fold increase in mature EDN1 levels, while embryos from Lines 1416 and 1408 had a 2.38-fold increase and 1.95-fold increase, respectively, in mature EDN1 when compared to control embryos (Fig. 1B). Embryos from Line 721 had a 1.84-fold increase in EDN1 levels. Similar results were obtained in a qRT-PCR assay for Edn1 mRNA in whole E10.5 embryos from Lines 1398 and 1416 (Supp. Fig. 1). These results confirm that levels of mature EDN1 were significantly elevated in all four lines, though differences between lines were not statistically significant.

As described above, Cre expression in the Wnt1-Cre strain results in gene deletion in cells that give rise to NCCs (Danielian et al., 1998). When crossed into the Cre reporter strain R26R, indelible β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity is observed in NCCs and their derivatives (Figure 2D, H, L and (Abe et al., 2007; Chai et al., 2000)). To confirm that the CBA-Edn1 transgene was driving spatial Edn1 expression in a Cre-dependent manner, we performed whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) analysis for Edn1 using E8.5, E9.5 and E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos Based on the EIA results, we focused our analysis on lines 1398 and 1416. In E8.5 control embryos, Edn1 expression was faintly observed in the first pharyngeal arch (Fig. 2A). In E8.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1398 line, broad Edn1 expression was observed in the head, in streams extending from the hindbrain rhombomere 1/2 and 4 regions and in the first pharyngeal arch (Fig. 2B). In embryos from line 1416, expression was primarily limited to the first pharyngeal arch mesenchyme (Fig. 2C). These patterns matched that of β-galactosidase staining in E8.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryos (Fig. 2D), in which Cre expression results in indelible staining in expressing cells and their daughter cells (Soriano, 1999). In E9.5 control embryos, Edn1 expression was present in the ectoderm lining the pharyngeal arches (Fig. 2E). In E9.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1398 (Fig. 2F) and 1416 (Fig. 2G) lines, Edn1 message was additionally observed in the pharyngeal arches and frontonasal prominence, again matching β-galactosidase staining in E9.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryos (Fig. 2H). In E10.5 control embryos, Edn1 expression was not detected in the pharyngeal arches or frontonasal prominence of the embryo, though expression was observed in the optic and otic placodes (Fig. 2I). In contrast, ectopic Edn1 expression in E10.5 CBA-Edn1; Wnt1-Cre embryos was observed in the mandibular and maxillary portions of the first pharyngeal arch and frontonasal prominence from lines 1398 (Fig. 2J) and 1416 (Fig. 2K). Weak expression could also be detected proximally to the pharyngeal arches in embryos from both lines (Fig. 2J, K). This pattern matched that of β-galactosidase staining in E10.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryos (Fig. 2F), including the more proximal staining, likely representing the developing cranial nerves. Similar staining was observed in E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from line 721 (Supp. Fig. 2C). We were unable to detect ectopic Edn1 expression in E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1408 line (Supp. Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Detection of Edn1 expression in CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Edn1 in E8.5 (A–C), E9.5 (E–G) and E10.5 (I–K) control (A, E, I) and mutant embryos from the 1398 (B, F, J) and 1416 (C, G, K) lines. Embryos are shown in lateral view. A–D. At E8.5, endogenous Edn1 expression was confined to first pharyngeal arch (1) (A). In contrast, ectopic Edn1 expression in embryos from the 1398 line was observed in the first pharyngeal arch (1), head and in streams from the hindbrain (arrows) (B). In embryos from line 1416, ectopic Edn1 expression was primarily only observed in the first arch (C). This patters was consistent with that observed in E8.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryo stained in whole-mount for β-gal activity (D). E–H. At E9.5, endogenous Edn1 expression was confined to the ectoderm and endoderm surrounding the mandibular portion of arch 1 and arches 2, 3 and 4 (E). The mesodermal core shows endogenous expression of Edn1 at this age (E). In E9.5 embryos from the 1398 (F) and 1416 (G) lines, ectopic Edn1 expression was observed in pharyngeal arches 1–4 and in the fronto-nasal prominence (fnp). A similar pattern was observed in E9.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryos (H). I–L. At E10.5, endogenous Edn1 expression was confine to the optic (opt) and otic placodes and the pharyngeal arch endoderm between arches 1 and 2 (I). In E10.5 embryos from the 1398 (J) and 1416 (K) lines, ectopic Edn1 expression was observed in pharyngeal arches 1–4 and in the (fnp). Weaker ectopic staining was observed proximal to arches in an area in which the cranial nerves form. This pattern was similar to that observed in E10.5 R26R;Wnt1-Cre embryos (L). ct, conotruncus; h, heart; mx1, maxillary prominence of first pharyngeal arch; md1, mandibular portion of first pharyngeal arch.

To continue our analysis, E18.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos were stained with alizarin red and alcian blue to allow visualization of bone and cartilage, respectively. Analysis of stained embryos revealed that distinct craniofacial malformations were present in three of the four lines (Fig. 3 and Supp. Fig. 3). Based on the EIA and ISH results, we continued our focus on lines 1398 and 1416. E18.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from Line 1398 presented with a complete homeotic transformation of the upper jaw (maxilla and jugal bones) into a mandible-like structure, complete with duplicated angular and condylar processes (Fig. 3B, K, N). The coronoid process of the mandible appeared to be lost due to fusion of the mandible and duplicated mandible (Fig. 3B, K, N). The malleus and incus were present, though additional cartilage was present that appeared to represent duplication of the malleus and incus (Fig. 4B). The tympanic ring and gonial bone were present but hypoplastic. An ectopic bone was present suggestive of duplicated gonial bone and/or part of the tympanic ring (Fig. 4B). The duplicated incus appeared similar to the structure identified as a duplicated malleus reported for embryos in which Edn1 was knocked into the Ednra locus (Sato et al., 2008a). In addition, the squamosal (Fig. 3B) and palatine (Fig. 3E) bones were hypoplastic, the latter resulting in a palatal cleft. E18.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from Line 1416 showed more significant defects that included a transformation of the maxilla into a mandible-like structure, complete with a duplicated Meckel’s cartilage and hypoplasia of the squamosal (Fig. 3C) and palatine (Fig. 3F) bones. As with embryos from line 1398, the condylar and angular processes were also duplicated, while the coronoid process was lost (Fig. 3C, L, O). Middle ear elements including the tympanic ring and malleus were present but hypoplastic (Fig. 4C). However, the remainder of the middle ear was composed of a large piece of ectopic cartilage, making identification of the incus or aberrant cartilage structures impossible (Fig. 4C). In addition, in 70% of CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1416 line, a large mid-facial cleft was also present (Fig. 3F, I). The cleft did not affect the transformation of the maxilla, suggesting that these two events are not related to each other. CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from line 721 resembled those from line 1416 (Supp. Fig. 3C, F, I). In contrast, craniofacial malformations were not present in CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from line 1408 (Supp. Fig. 3B, E, H). Overall, the presence of ectopic Edn1 appears to correlate with the presence of defects in the developing jaw region. However, based on the comparison of ISH/phenotype results with the EIA results, there are likely differences between EDN1 levels that are not detectable by ISH, potentially reflecting chromatin dynamics of the insertion site (Li et al., 2002; Pikaart et al., 1998; Prioleau et al., 1999; Ryan et al., 1989)

Figure 3. Skull analysis of E18.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos.

A–O. Alizarin red and alcian blue stained skulls to visualize bone and cartilage, respectively. A–C: Lateral view of skulls. D–F: Ventral view of the skull. G–I: Dorsal view of the skull. J–L. Lateral view of lower and upper jaw structures. M–O. Ventral view of lower and upper jaw structures. Distinct craniofacial malformations were observed in embryos from lines 1398 (B, E, H, K, N) and 1416 (C, F, I, L, O) when compared to control embryos (A, D, G, J, M). Both lines presented with transformation of the maxilla (mx) into a mandible-like structure (md*) that was fused with the mandible (md). The duplicated mandible contained a duplicated Meckel’s cartilage (mc*), absent jugal bones (j) and deformed squamosal (sq) bones, absent or hypoplastic palatine (pl) and basisphenoid (bs) bones, and a palatal cleft (arrow). 70% of embryos from line 1416 (F, I) also presented with a large mid-facial cleft. ap, angular process; ap*, duplicated angular process; bo, basisoccipital; cdp, condylar process; cdp*, duplicated condylar process; crp, coronoid process; f, frontal bone; h, hyoid; j, jugal; n, nasal bone; p, parietal bone; pmx, pre-maxilla; pt, pterygoid; sq, squamosal bone; ty, tympanic ring; zps, zygomatic process of the squamosal bone.

Figure 4. Middle ear defects in CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos.

Dissected middle ear structures after staining with alizarin red and alcian blue to visualize bone and cartilage, respectively. A. The middle ear from a control embryo, showing the three middle ear ossicles: malleus (m), incus (i) and stapes (s) in addition Meckel’s cartilage (mc) and the gonial bone (g). B. In CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from line 1398, middle ear defects included an imperfect duplication of the malleus (m*) and incus (i*). There was also additional bone present that could be a duplicated but malformed tympanic ring (ty*) or gonial (g*) bone, though the poor shape prevented a definitive identification. C. In CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from line 1416, the malleus and tympanic ring were present but hypoplastic. The remainder of the middle ear was composed of an unidentifiable ectopic cartilage.

Although homeotic transformation of the maxilla into a mandible-like structure was apparent in mice in which an Edn1 cDNA was inserted into the Ednra locus (EdnraEdn1/+), a midfacial cleft was not observed (Sato et al., 2008a). Without EIA measurement of mature EDN1 levels in EdnraEdn1/+embryos, it is impossible to compare the EDN1 levels between EdnraEdn1/+ and CBA-Edn1;Cre embryos. However, it is conceivable that Edn1 expression is higher in CBA-Edn1;Cre transgenic embryos than that coming from the additional one copy found in EdnraEdn1/+embryos and that this subsequently leads to the midfacial cleft in CBA-Edn1;Cre embryos. We also cannot rule out the possibility that the phenotypic outcome of increased EDN1 in EdnraEdn1/+embryos is partially masked due to reduced EDNRA signaling that occurs when Ednra gene dosage is reduced (Vieux-Rochas et al., 2010).

EDNRA signaling in the mandibular pharyngeal arches initiates a cascade of gene expression required for establishing the identity of NCCs in the mandibular arch (Ruest et al., 2004) (Clouthier et al., 2010). We thus expected that EDNRA-dependent gene expression normally confined to the mandibular portion of the first pharyngeal arch would expand into the maxillary prominence, something observed previously in EdnraEdn1/+ embryos (Sato et al., 2008a). Indeed, expression of Dlx3 expanded in CBA-Edn1 embryos from both the 1398 (Fig. 5B) and 1416 (Fig. 5C) lines, with this expanded expression observed in the rostral mandibular arch mesenchyme, overlying rostral ectoderm and maxillary prominence ectoderm. In CBA-Edn1 embryos from the 1416 line, this maxillary expression extended into the lambdoidal junction (arrow in Fig. 5C). Similarly, aberrant Dlx5 expression was observed extending from the mandibular arch into the maxillary prominence in both lines (Fig. 5E, F). These findings suggest that upregulation of EDRNA signaling in the maxillary prominence leads to an EDNRA-dependent gene expression program that subsequently leads to homeosis of maxillary structures.

Figure 5. Disrupted gene expression in E10.5 CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos.

A–F. Lateral view of embryos from lines 1398 (B, E) and 1416 (C, F) processed for whole mount in situ hybridization (ISH) analysis using digoxigenin-labeled probes. In embryos from both lines, there was ectopic expression of Dlx3 in the rostral arch mesenchyme and overlying ectoderm of the mandibular arch and in the maxillary prominence around the lamdoidal junction (arrows in B and C). Likewise, a proximal expansion of Dlx5 towards the maxillary prominence was observed (arrow in E and F). 1. first pharyngeal arch; 2. second pharyngeal arch.

It is surprising that we did not see more substantial changes in mandible development, though major defects were also not observed in embryos in which Edn1 was knocked into the Ednra locus (Sato et al., 2008a). We have previously shown that there is a threshold level of EDN1 required for normal lower jaw development during a narrow window of arch development (Clouthier et al., 2003), with EDN1 activity dispensable after E9.5 (Clouthier et al., 2003; Ruest et al., 2005). Taken with the current findings, it is likely that EDN1 activity patterns all cells within a region (meaning that there is not a gradient of action), a hypothesis supported by in vivo rescue experiments in edn1 mutant zebrafish embryos (Miller et al., 2000b). In addition, even though the levels remain high later in arch development, the ability to respond to EDN1 likely diminishes.

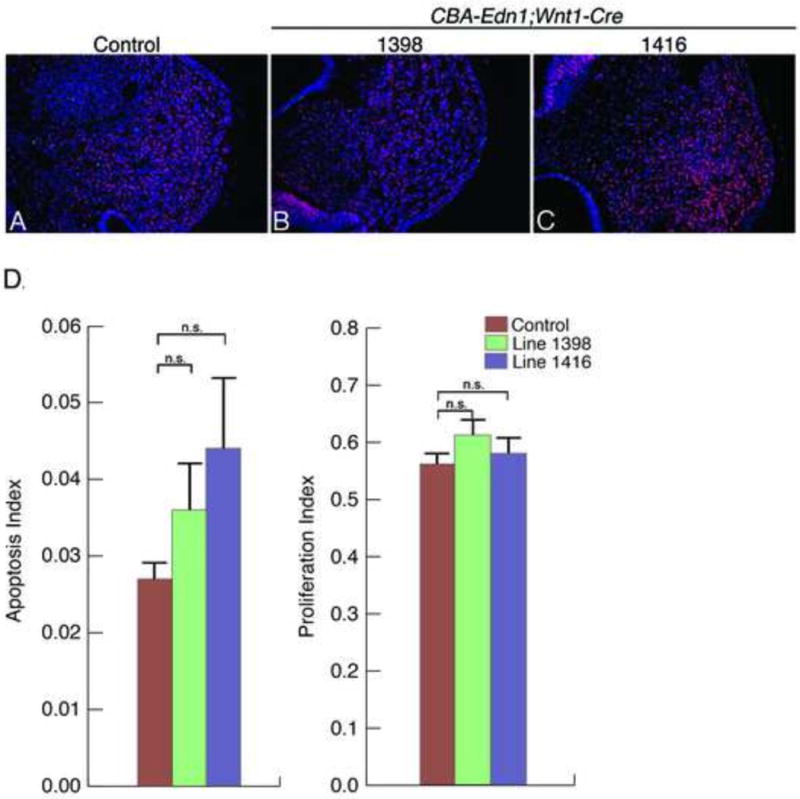

Elevated EDN1 levels do not lead to changes in NCC proliferation or survival

Increased Edn1 expression in cranial NCCs could lead to midfacial clefts for several reasons, including disrupted NCC migration, proliferation or survival. A defect in migration seems less likely, as EDN1 typically acts as an attractant for multiple cell types, including astrocytes (Kuhlmann et al., 2005) and both trophoblast (Liu et al., 2012) and chondrosarcoma (Wu et al., 2013) cells. In addition, loss of EDNRA signaling does not lead to detectable changes in NCC migration into the mandibular portion of the first arch (Abe et al., 2007), further suggesting that EDN1 functions at time periods after NCC migration is complete. In contrast, EDN1 has been associated with proliferation of multiple cell types, including endothelial (Kuhlmann et al., 2005) and colon cancer cells (Grant et al., 2007), while also often associated with inhibition of apoptosis in multiple cellular settings (Del Bufalo et al., 2002; McWhinnie et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2005; Shichiri et al., 2000). To determine whether the observed midfacial clefts could be due to early changes in NCC proliferation and/or survival within the developing maxillary prominences, we performed both cell proliferation and apoptosis analysis. These analyses were performed on the same sections through two planes of the maxillary prominence in E10.5 embryos. At this age, we did not observe significant differences in either proliferation or apoptosis of cells in the maxillary prominence (Fig. 6A–D) between control and CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1398 and 1416 lines. The apoptosis index in embryos from Line 1416 trended higher (p=0.08), with the variation in cell death between embryos also higher in this line than in Line 1398 (data not shown). Higher cell death in some Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos from the 1416 line may point to embryos that will go on to show a midfacial cleft at E18.5, though it is currently not possible to prove such a correlation. Overall, our results suggest that Edn1 overexpression does not lead to an immediate change in NCC-derived mesenchyme growth or survival during their initial patterning period. Rather, the observed defects likely arise during later differentiation of the NCC derived mesenchyme. Similar midfacial defects have recently been described in embryos containing phosphorylation variants of the bHLH factor Hand1 (Firulli et al., 2014). While the basis for the defects in these embryos is not completely clear, Hand1 is a downstream mediator of EDNRA signaling, suggesting the cellular affect of the two may share a common mechanism. Further detailed analysis of gene expression associated with midline development during early facial patterning will be required to determine address these questions.

Figure 6. Cell proliferation and death in CBA-Edn1;Wnt1-Cre embryos.

A–C. Representative sections showing the maxillary prominence region of E10.5 control embryos (A) and E10.5 embryos from lines 1398 (B) and 1416 (C). Cell proliferation was detected and quantified on sections from EdU-treated embryos after EdU-incorporation staining (red). Cell death (TUNEL) was detected and quantified on the same sections (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). D. The total number of cells (DAPI) and labeled cells (TUNEL or EdU) were counted and the apoptosis and proliferation indexes calculated as the total number of TUNEL- or EdU-positive cells divided by the total number of DAPI-positive cells. There was no significant differences (n.s.) in either proliferating cells (1398: p=0.1; 1416: p=0.5) or cells undergoing apoptosis (1398: p=0.2; 1416: p=0.08) relative to control embryos. Error bars represent standard error.

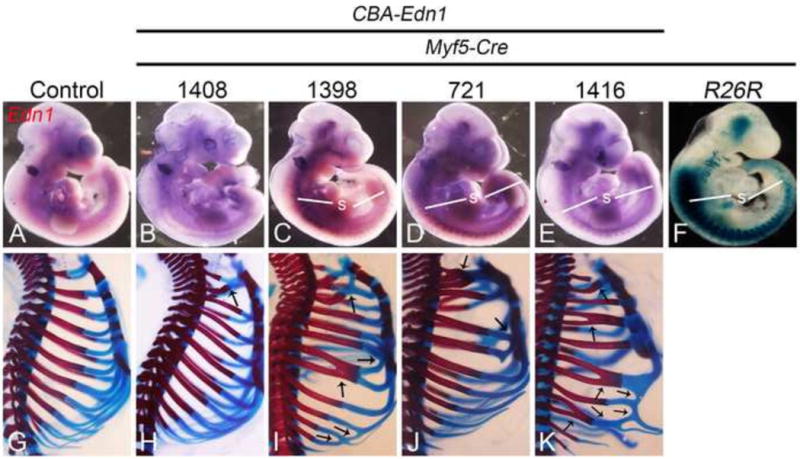

Defects in CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryos

To illustrate that Edn1 expression could be induced in other Cre strains, we took advantage of the mesoderm-specific Cre strain Myf5-Cre (Tallquist et al., 2000). This strain was crossed into our four CBA-Edn1 strains and embryos collected at E10.5 for whole mount ISH. In three of our four lines, ectopic Edn1 expression was observed in somitic mesoderm and brain (Fig. 7C–E) in a similar pattern to that observed for β-gal staining in E10.5 R26R;Myf5-Cre embryos (Fig. 7F). We were unable to detect ectopic Edn1 expression in embryos from Line 1408 (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that Edn1 expression in at least three of our CBA-Edn1 transgenic mouse strains can be achieved at likely any age through the use of tissue and/or temporally regulated Cre transgenic mouse strains.

Figure 7. Detection of Edn1 expression and phenotypic analysis in CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryos.

A–E. Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis of Edn1 expression in E10.5 control (A) and CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryos (B–E). Ectopic Edn1 expression was undetectable in embryos from line 1408 (B). In contrast, embryos from lines 1398 (C), 721 (D) and 1416 (E) had ectopic Edn1 expression in the somites (s). F. Analysis of staining in E10.5 R26R;Myf5-Cre embryos stained in whole-mount for β-gal activity. Staining was observed in several sites, including the somites, core pharyngeal arch mesoderm, and head. G–K. Lateral view of the trunk region from alizarin red/alcian blue-stained E18.5 CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryos from all four lines. Embryos from all lines displayed various rib abnormalities, characterized by random fusions of bony and cartilaginous portions of different ribs (arrows), though the severity and number of fusions differed between lines.

To determine whether aberrant Edn1 expression induced skeletal changes in CBA-Edn1 ;Myf5-Cre embryos, bone and cartilage-stained E18.5 embryos from all four lines were examined. Because of the ectopic Edn1 expression in somites, we first examined the thoracic skeleton. In all four lines, fusions between the first and second costal cartilages were observed (Fig. 7H–K), with varying other costal cartilage fusions observed in embryos from lines 1398, 1408 and 1416 (Figs. 7I–K). In lines 1398, 1408 and 1416, fusions were also observed between adjoining ribs (Fig. 7I–K). There did not appear to be a specific pattern to the fusions, as they were not bilaterally symmetric in a single embryo (data not shown). However, while the pattern of defects differed between sides, the overall severity of rib defects was similar between embryos of a specific line (data not shown). These changes may reflect defects in dermamyotome development due to EDN1 action. Myf5 is expressed in the dorsomedial aspects of the dermamyotome (Cossu et al., 1996), with the development of both ribs and dermamytome-derived intercostal muscles disrupted in Myf5Jae/Jae mutants (Kablar et al., 1997). Pdfga expression in Myf5Jae/Jae mutant embryos is downregulated in the myotome, suggesting that PDGFA is a direct or indirect target of MYF5 during myotome development (Tallquist et al., 2000). While expression of Pdgfa from the Myf5 locus (Myf5PDGFA/PDGFA) rescues the rib formation defects observed in Myf5ae/Jae mutant embryos, extensive fusions between ribs exist (Tallquist et al., 2000). These fusions have been hypothesized to result from the intercostal muscle defects (Tallquist et al., 2000), since the intercostal muscles normally separate forming ribs (Huang et al., 2000). It is thus plausible that expression of Edn1 in the dermamyotome disrupts intercostal development, potentially through induction of early cell death. Similar rib fusions are observed in Splotch mutants, in which loss of Pax3 results in failure to maintain Pdgfra expression and subsequent elevated apoptosis in the somites by E12.5 (Conway et al., 1997). Similar apoptosis patterns have been found in Pdgfra mutant embryos (Soriano, 1997). Whether EDN1 affects these pathways or influences cellular patterning and survival will require further analysis.

While rib changes were evident in all lines, one CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryo from the 1416 line had a partial homeotic transformation of the maxilla into a mandible (Supp. Figure. 4). Because this change has to result from changes in NCC patterning, this implies a non-cell autonomous action of EDN1 derived from mesodermal cells in the pharyngeal arches. While ectopic Edn1 expression in the pharyngeal arch region does not appear robust, the source of EDN1 is almost certainly from the facial region, as pre-pro-EDN1 has a half-life of around 15 min (Inoue et al., 1989) and typically acts close to its site of activation from an inactive to active form by endothelin converting enzyme-1 (ECE1) (Yanagisawa et al., 1998b). This mode of non-cell autonomous action of EDN1 matches that of its normal mode of action during mandibular arch patterning, when EDN1 from primarily the ectoderm drives EDNRA signaling (Nair et al., 2007; Tavares et al., 2012). While it is possible that EDN1 caused changes affecting migration, proliferation or survival of NCCs prior to their arrival in the arches of CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryos, such changes were not observed even when EDN1 activity occurred in NCCs prior to the onset of migration (via Wnt1-Cre activity). This further indicates that EDN1 action occurs in the arches.

We cannot completely exclude the possibility that Cre expression is leaky in the Myf5-Cre line, resulting in Cre activity in NCCs (and thus a cell autonomous explanation), though Cre expression in Myf5-Cre mice was achieved by inserting Cre into the Myf5 locus (Tallquist et al., 2000). In addition, none of the 48 studies associated with this strain have reported expression of Cre in NCCs (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/007893.html). Finally, we have previously shown using R26R;Myf5-Cre embryos that β-gal-positive cells are not observed in either NCCs or their daughter cells (Tavares et al., 2012). Together, these studies support the idea that the skull changes observed in CBA-Edn1;Myf5-Cre embryo occur in a non-cell autonomous manner.

In conclusion, we have created four lines of CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice in which the expression of Edn1 is prevented by the inclusion of a strong stop cassette between the CBA promoter/enhancer sequence and EDN1. As the stop cassette is flanked by loxP sites, Edn1 expression can be induced in a spatio-temporal manner in both embryos and adult mice by crossing Edn1 transgenic mice with appropriate Cre transgenic mouse strains. These mice should be useful in further understanding mechanisms of EDN1 action during NCC patterning and early vasculature development. In addition, it is likely that these mice can be used to both understand how EDN1 activation in numerous adult diseases contributes to the disease phenotype and determine the benefit of pharmaceutical intervention of EDN1 action as a treatment paradigm.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Creation of conditional chicken ®-actin-endothelin-1 transgenic mice is described.

Tissue-specific Edn1 expression is induced by two different Cre transgenic lines.

Cre expression results in development defects of varying severity between lines.

These mice will be useful for further analysis of EDN1 action in embryos and adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Holly Buttermore and Elvin Garcia for technical assistance. CBA-Edn1 transgenic mice were made at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Transgenic Technology Center under direction of Dr. Robert E. Hammer. This work was supported by grants from NIH/NIDCR (DE014181, DE018899 and DE023050) to D.E.C.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health, Contract grant number: DE014181, DE018899 and DE023050 (to D.E.C).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abe M, Ruest LB, Clouthier DE. Fate of cranial neural crest cells during craniofacial development in endothelin-A receptor deficient mice. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:97–105. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.062237ma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri F, Virdis A, Fritsch-Neves M, Iglarz M, Seidah NG, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL, Schiffrin RL. Endothelium-restricted overexpression of human endothelin-1 causes vascular remodeling and endothleial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144462.08345.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerio AD, Bufalino D, Bresnick M, Bell C, Brill S. Inflammatory bowel disease and endothelin-1: a review. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2005;28:208–213. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200504000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato A, Rosano L. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer progression: a crucial role for the endothelin axis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:85–94. doi: 10.1159/000101307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron F, Woods C, Kuhn K, Bishop J, Howard MJ, Clouthier DE. Downregulation of Dlx5 and Dlx6 expression by Hand2 is essential for initiation of tongue morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138:2249–2259. doi: 10.1242/dev.056929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Han J, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Comerford SA, Hammer RE. Hepatic fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, and a lipodystrophy-like syndrome in PEPCK-TGF-b1 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2697–2713. doi: 10.1172/JCI119815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Garcia E, Schilling TF. Regulation of facial morphogenesis by endothelin signaling: insights from mouse and fish. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2962–2973. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Hosoda K, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Yanagisawa H, Kuwaki T, Kumada M, Hammer RE, Yanagisawa M. Cranial and cardiac neural crest defects in endothelin-A receptor-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:813–824. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Passos-Bueno MR, Tavares ALP, Lyonnet S, Amiel J, Gordon CT. Understanding the basis of Auriculocondylar syndrome: Insights from human, mouse and zebrafish studies. Am J Med Genet, Part C. 2013;163:306–317. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Williams SC, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Cell-autonomous and nonautonomous actions of endothelin-A receptor signaling in craniofacial and cardiovascular development. Dev Biol. 2003;261:506–519. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouthier DE, Williams SC, Yanagisawa H, Wieduwilt M, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Signaling pathways crucial for craniofacial development revealed by endothelin-A receptor-deficient mice. Dev Biol. 2000;217:10–24. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway SJ, Henderson DJ, Copp AJ. Pax3 is required for cardiac neural crest migration in the mouse: evidence from the splotch (Sp2H) mutant. Development. 1997;124:505–514. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Kelly R, Tajbakhsh S, Di Donna S, Vivarelli E, Buckingham M. Activation of different myogenic pathways: myf-5 is induced by the neural tube and MyoD by the dorsal ectoderm in mouse paraxial mesoderm. Development. 1996;122:429–437. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP. Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Current Biol. 1998;8:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bufalo D, Di Castro V, Biroccio A, Varmi M, Salani D, Rosano L, Trisciuoglio D, Spinella F, Bagnato A. Endothelin-1 protects ovarian carcinoma cells against paclitaxel-induced apoptosis: requirement for Akt activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:524–532. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaun N, Webb DJ, Kluth DC. Endothelin-1 and the kidney–beyond BP. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:720–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington KL. A role for natriuretic peptides as well as endothelins in the hypoxic lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 1999;66:208–209. doi: 10.1159/000029378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Cis-acting regulatory sequences governing Wnt-1 expression in the developing mouse CNS. Development. 1994;120:2213–2224. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firulli BA, Fuchs RK, Vincentz JW, Clouthier DE, Firulli AB. Hand1 phosphoregulation within the distal arch neural crest is essential for craniofacial morphogenesis. Development. 2014;141:3050–3061. doi: 10.1242/dev.107680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BD, Machado FS, Tanowitz HB, Desruisseaux MS. Endothelin-1 and its role in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Life Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.04.021. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardini E, Buelli S, Benigni A. Endothelin in chronic proteinuric kidney disease. Cont Nephrol. 2011;172:171–184. doi: 10.1159/000328697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K, Knowles J, Dawas K, Burnstock G, Taylor I, Loizidou M. Mechanisms of endothelin 1-stimulated proliferation in colorectal cancer cell lines. Br J Surg. 2007;94:106–112. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TR, Gadea A, Dupree J, Kerninon C, Nait-Oumesmar B, Aguirre A, Gallo V. Astrocyte-derived endothelin-1 inhibits remyelination through notch activation. Neuron. 2014;81:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufschild T, Shaw SG, Kesselring J, Flammer J. Increased endothelin-1 plasma levels in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuro Ophthalmol. 2001;21:37–38. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocher B, Thone-Reineke C, Rohmeiss P, Schmager F, Slowinski T, Burst V, Siegmund F, Quertermous T, Bauer C, Neumayer HH, Schleuning WD, Theuring F. Endothelin-1 transgenic mice develop glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and renal cysts but not hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1380–1389. doi: 10.1172/JCI119297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Zhi Q, Schmidt C, Wilting J, Brand-Saberi B, Christ B. Sclerotomal origin of the ribs. Development. 2000;127:527–532. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Mitsui Y, Kobayashi M, Masaki T. The human preproendothelin-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14954–14959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii M, Han J, Yen HY, Sucov HM, Chai Y, Maxson JRE. Combined deficiencies of Msx1 and Msx2 cause impaired patterning and survival of the cranial neural crest. Development. 2005;132:4937–4950. doi: 10.1242/dev.02072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kablar B, Krastel K, Ying C, Asakura A, Tapscott SJ, Rudnicki MA. MyoD and Myf-5 differentially regulate the development of limb versus trunk skeletal muscle. Development. 1997;124:4729–4738. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzierski RM, Grayburn PA, Kisanuki YY, Williams CS, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Schneider MD, Yanagisawa M. Cardiomyocyte-specific endothelin a receptor knockout mice have normal cardiac function and an unaltered hypertrophic response to angiotensin II and isoproterenol. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8226–8232. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8226-8232.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ullmann B, Walker M, Miller CT, Crump JG. Endothelin 1-mediated regulation of pharyngeal bone development in zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:1339–1351. doi: 10.1242/dev.00338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles J, Loizidou M, Taylor I. Endothelin-1 and angiogenesis in cancer. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2005;3:309–314. doi: 10.2174/157016105774329462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann CR, Most AK, Li F, Munz BM, Schaefer CA, Walther S, Raedle-Hurst T, Waldecker B, Piper HM, Tillmanns H, Wiecha J. Endothelin-1-induced proliferation of human endothelial cells depends on activation of K+ channels and Ca+ influx. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Kurihara H, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Maemura K, Nagai R, Oda H, Kuwaki T, Cao WH, Kamada N, Jishage K, Ouchi Y, Azuma S, Toyoda Y, Ishikawa T, Kumada M, Yazaki Y. Elevated blood pressure and craniofacial abnormalities in mice deficient in endothelin-1. Nature. 1994;368:703–710. doi: 10.1038/368703a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JW, Wong WT, Koon HW, Mo FM, Tam S, Huang Y, Vanhoutte PM, Chung SS, Chung SK. Transgenic mice over-expressing ET-1 in the endothelial cells develop systemic hypertension with altered vascular reactivity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang M, Han H, Rohde A, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Evidence that DNase I hypersensitive site 5 of the human beta-globin locus control region functions as a chromosomal insulator in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2484–2491. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Li Q, Na Q, Liu C. Endothelin-1 stimulates human trophoblast cell migration through Cdc42 activation. Placenta. 2012;33:712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AC, Chen AY, Hung VK, Yaw LP, Fung MK, Ho MC, Tsang MC, Chung SS, Chung SK. Endothelin-1 overexpression leads to further water accumulation and brain edema after middle cerebral artery occlusion via aquaporin 4 expression in astrocytic end-feet. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:998–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maemura K, Kurihara H, Kurihara Y, Oda H, Ishikawa T, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Yazaki Y. Sequence analysis, chromosomal location, and developmental expression of the mouse preproendothelin-1 gene. Genomics. 1996;31:177–184. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhinnie R, Pechkovsky DV, Zhou D, Lane D, Halayko AJ, Knight DA, Bai TR. Endothelin-1 induces hypertrophy and inhibits apoptosis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:L278–286. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00111.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi XS, Zhang X, Feng Q, Lo AC, Chung SK, So KF. Progressive retinal degeneration in transgenic mice with overexpression of endothelin-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53:4842–4851. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Kimmel CB. Morpholino phenocopies of endothelin 1 (sucker) and other anterior arch class mutations. Genesis. 2001;30:186–187. doi: 10.1002/gene.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Schilling TF, Lee K, Parker J, Kimmel CB. sucker encodes a zebrafish Endothelin-1 required for ventral pharyngeal arch development. Development. 2000a;127:3815–3828. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Schilling TF, Lee KH, Parker J, Kimmel CB. sucker encodes a zebrafish Endothelin-1 required for ventral pharyngeal arch development. Development. 2000b;127:3815–3838. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Swartz ME, Khuu PA, Walker MB, Eberhart JK, Kimmel CB. mef2ca is required in cranial neural crest to effect Endothelin1 signaling in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2007;308:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. Endothelin and vascular function in liver disease. Gut. 2004;53:159–161. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhouse RC, Webb DJ, Kluth DC, Dhaun N. Endothelin antagonism and its role in the treatment of hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15:489–496. doi: 10.1007/s11906-013-0380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CR. Mechanisms of vasculopathy in sickle cell disease and thalassemia. Hematology. 2008;2008:177–185. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair S, Li W, Cornell R, Schilling TF. Requirements for endothelin type-A receptors and endothelin-1 signaling in the facial ectoderm for the patterning of skeletogenic neural crest cells in zebrafish. Development. 2007;134:335–345. doi: 10.1242/dev.02704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JB, Udan MS, Guruli G, Pflug BR. Endothelin-1 inhibits apoptosis in prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:631–637. doi: 10.1593/neo.04787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki H, Kurihara Y, Tonami K, Watatani S, Kurihara H. Endothelin-1 regulates the dorsoventral branchial arch patterning in mice. Mech Dev. 2004;121:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JC, Tayler HM, Love S. Endothelin-converting enzyme-1 activity, endothelin-1 production, and free radical-dependent vasoconstriction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36:577–587. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikaart MJ, Recillas-Targa F, Felsenfeld G. Loss of transcriptional activity of a transgene is accompanied by DNA methylation and histone deacetylation and is prevented by insulators. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2852–2862. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polikepahad S, Moore RM, Venugopal CS. Endothelins and airways–a short review. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2006;119:3–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prioleau MN, Nony P, Simpson M, Felsenfeld G. An insulator element and condensed chromatin region separate the chicken beta-globin locus from an independently regulated erythroid-specific folate receptor gene. EMBO J. 1999;18:4035–4048. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder MJ, Green GE, Park SS, Stamper BD, Gordon CT, Johnson JM, Cunniff CM, Smith JD, Emery SB, Lyonnet S, Amiel J, Holder M, Heggie AA, Bamshad MJ, Nickerson DA, Cox TC, Hing AV, Horst JA, Cunningham ML. A human homeotic transformation tesulting from mutations in PLCB4 and GNAI3 causes auriculocondylar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruest LB, Kedzierski R, Yanagisawa M, Clouthier DE. Deletion of the endothelin-A receptor gene within the developing mandible. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319:447–454. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0988-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruest LB, Clouthier DE. Elucidating timing and function of endothelin-A receptor signaling during craniofacial development using neural crest cell-specific gene deletion and receptor antagonism. Dev Biol. 2009;328:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruest LB, Xiang X, Lim KC, Levi G, Clouthier DE. Endothelin-A receptor-dependent and -independent signaling pathways in establishing mandibular identity. Development. 2004;131:4413–4423. doi: 10.1242/dev.01291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TM, Behringer RR, Martin NC, Townes TM, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. A single erythroid-specific DNase I super-hypersensitive site activates high levels of human beta-globin gene expression in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1989;3:314–323. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Kamiyoshi A, Watanabe S, Sato M, Shindo T. Rapid zygosity determination in mice by SYBR Green real-time genomic PCR of a crude DNA solution. Transgenic Res. 2008;17:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Kawamura Y, Asai R, Amano T, Uchijima Y, Dettlaff-Swiercz DA, Offermanns S, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H. Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange reveals the selective use of Gq/G1 1-dependent and -independent endothelin 1-endothelin type A receptor signaling in pharyngeal arch development. Development. 2008a;135:755–765. doi: 10.1242/dev.012708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Kurihara Y, Asai R, Kawamura Y, Tonami K, Uchijima Y, Heude E, Ekker M, Levi G, Kurihara H. An endothelin-1 switch specifies maxillomandibular identity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008b;105:18806–18811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807345105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichiri M, Yokokura M, Marumo F, Hirata Y. Endothelin-1 inhibits apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells induced by nitric oxide and serum deprivation via MAP kinase pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:989–997. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo T, Kurihara H, Maemura K, Kurihara Y, Ueda O, Suzuki H, Kuwaki T, Ju KH, Wang Y, Ebihara A, Nishimatsu H, Moriyama N, Fukuda M, Akimoto Y, Hirano H, Morita H, Kumada M, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Kimura K. Renal damage and salt-dependent hypertension in aged transgenic mice overexpressing endothelin-1. J Mol Med. 2002;80:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohet RV, Kisanuki YY, Zhao XS, Siddiquee Z, Franco F, Yanagisawa H. Mice with cardiomyocyte-specific disruption of the endothelin-1 gene are resistant to hyperthyroid cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2088–2093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307159101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. The PDGFa receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Gen. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed JS, Pollock DM. Endothelin, kidney disease, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:1142–1145. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi R, Ohnaka K, Takasaki C, Ohashi M, Nawata H. Multiple subtypes of endothelin receptors in porcine tissues: characterization by ligand binding, affinity labeling and regional distribution. Regul Pept. 1991;32:23–37. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Weismann KE, Hellstrom M, Soriano P. Early myotome specification regulates PDFGA expression and axial skeleton development. Development. 2000;127:5059–5070. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares ALP, Garcia EL, Kuhn K, Woods CM, Williams T, Clouthier DE. Ectodermal-derived Endothelin1 is required for patterning the distal and intermediate domains of the mouse mandibular arch. Dev Biol. 2012;371:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieux-Rochas M, Mantero S, Heude E, Barbieri O, Astigiano S, Couly G, Kurihara H, Levi G, Merlo GR. Spatio-temporal dynamics of gene expression of the Edn1-Dlx5/6 pathway during development of the lower jaw. Genesis. 2010;48:262–373. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MB, Miller CT, Swartz ME, Eberhart JK, Kimmel CB. phospholipase C, beta 3 is required for Endothelin1 regulation of pharyngeal arch patterning in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2007;304:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MB, Miller CT, Talbot JC, Stock DW, Kimmel CB. Zebrafish furin mutants reveal intricacies in regulating Endothelin1 signaling in craniofacial patterning. Dev Biol. 2006;295:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MH, Chen LM, Hsu HH, Lin JA, Lin YM, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Huang CY, Tang CH. Endothelin-1 enhances cell migration through COX-2 up-regulation in human chondrosarcoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3355–3364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa H, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Clouthier DE, Yanagisawa M. Role of Endothelin-1/Endothelin-A receptor-mediated signaling pathway in the aortic arch patterning in mice. J Clin Invest. 1998a;102:22–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa H, Yanagisawa M, Kapur RP, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Clouthier DE, de Wit D, Emoto N, Hammer RE. Dual genetic pathways of endothelin-mediated intercellular signaling revealed by targeted disruption of endothelin converting enzyme-1 gene. Development. 1998b;125:825–836. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M. The endothelin system: a new target for therapeutic intervention. Circulation. 1994;89:1320–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.