Abstract

We describe a human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program implemented since 2007 in Geneva Canton, Switzerland, that used school services, a public hospital, and private physicians as vaccination providers. We assessed program performance with the evolution of immunization coverage during the first four years of program implementation. We measured vaccination coverage of the target population using individual records of vaccination status collected by service providers and transmitted to the Geneva Canton Medical Office. The target population was 20,541 adolescent girls aged 11–19 years as of September 1, 2008, who resided in the canton when the program began. As of June 30, 2012, HPV vaccination coverage was 72.6% and 74.8% in targeted cohorts for three and two doses, respectively. The global coverage for three doses increased by 27 percentage points from December 2009 to June 2012. Coverage for girls aged 16–18 years at the beginning of the program reached 80% or more four years into the program. High coverage by this HPV vaccination program in Geneva was likely related to free vaccination and easy access to the vaccine using a combination of delivery services, including school health services, a public hospital, and private physicians, covering most eligible adolescent girls.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) represents a group of sexually transmitted viruses of particular interest because of their high prevalence and strong causal association with cervical cancer.1 Cervical cancer is the second most frequently occurring cancer in the world for women.2 Every year in Switzerland, 5,000 women present with a precancerous lesion of the cervix or an in situ carcinoma, and 320 women present with an invasive cervical carcinoma requiring surgical or laser treatment.1 Half of the women presenting with a precancerous lesion of the cervix or an in situ carcinoma are <50 years of age at the time of diagnosis.3 In Geneva, Switzerland, 400 cases of in situ and 30 cases of invasive cervical cancer are diagnosed annually, resulting in 5–10 deaths per year.4 Both morbidity and mortality associated with this infection can be reduced through vaccination.5

Two vaccines to prevent HPV infections have been developed by two companies, Sanofi Pasteur MSD and GSK,6–8 that decrease the incidence of precancerous lesions of the cervix and also that of genital warts, another HPV-related infection.9 Since 2006, following the European Medicine Agency approval of Cervarix® and Gardasil®, these two vaccines have been used in most European countries.5 Cervarix targets HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, and -45, the five most common cancer-causing viral types, including most causes of adenocarcinoma. Gardasil targets HPV-16, -18, and -31, the three common squamous cell cancer-causing viral types, as well as HPV-6 and -11, which are associated with genital warts and respiratory papillomatosis.10 As in the United States, national recommendations on immunization in Switzerland are implemented by states (cantons), which have a wide level of autonomy on health-related matters. In Geneva Canton, the operational strategy was to vaccinate as many eligible (i.e., aged 11–18 years) adolescent girls as possible by sending them individual letters and making vaccination free of charge through all potential health-care providers of this age group (e.g., pediatricians, general practitioners, gynecologists, public hospital clinics, and school health services). This article provides an overview of the establishment of a publicly funded HPV vaccination program in Geneva Canton, preliminary coverage results, and key features of success.

METHODS

Implementation of the HPV vaccination program in Geneva

In Switzerland, immunization policy is defined by the federal immunization commission. Vaccines for children are provided free of charge through the mandatory universal health insurance program. Vaccinations are mostly administered by private physicians and school health services in public schools. In some cantons, state-employed public health nurses and physicians provide preventive services such as vaccination and health education in publicly funded schools. Since 2007, the Swiss Federal Vaccination Commission has recommended HPV vaccination free of charge for adolescent girls aged 11–19 years11 through a cantonal vaccination program. During the 2007–2008 school year, Geneva Canton was among the first cantons in Switzerland to plan and implement such a canton-wide HPV vaccination program through three different and complementary service providers: in public schools, by private physicians, and by the Geneva University Hospital.

During the first year of the program (2007–2008), only the 2,150 girls in seventh grade in public schools of the canton (i.e., aged 11–12 years) could be vaccinated by the School Health Service (i.e., Service Santé de la Jeunesse [SSJ]). Since the 2008–2009 school year, vaccination has been offered free of charge to adolescent girls aged 11–19 years, amounting to approximately 4,000 eligible adolescent girls each year. Girls can be vaccinated by one of three service providers: in public schools (since 2007–2008), by private physicians, or by the Geneva University Hospital.

Vaccination data monitoring was available through a list of girls who had received their first, second, and third shots and were sent three times per year to the State Medical Office. Participating private practitioners (i.e., pediatricians, gynecologists, internists, and general practitioners) received the vaccine doses free of charge. Every three months, they transmitted individual electronic vaccination forms—including name; date of birth; and number and date of first, second, or third dose—to the State Medical Office. Geneva University Hospital offered vaccination to those who did not have a private physician or who could not or did not want to use SSJ. They applied the same procedure as private practitioners and submitted vaccination forms to the State Medical Office every three months.

Program promotion

Geneva University Hospital vaccination was offered on a voluntary basis. Public information and the vaccine promotion were therefore essential to reach the targeted coverage of 80% with three doses. All service providers contributed to this activity and received promotional documents, including posters and brochures prepared and printed locally or by the Federal Office of Public Health. On the basis of the federal immunization commission positioning, the Federal Office of Public Health makes official recommendations and ensures that recommended vaccines are included in the list of services covered free of charge by the national insurance plan. All eligible adolescent girls (or their parents if they were <16 years of age) received a letter from the State Medical Office containing three vaccination vouchers for the first, second, and third injections. When the state HPV vaccination program was launched, all teen girls aged 16–19 years—16 being the age of sexual majority in Switzerland—or their parents if they were 11–15 years of age received a letter with information on the HPV vaccine. This letter included three vouchers to complete and present at the time of vaccination. These vouchers were sent by the health-care provider to the HPV program coordinator and used for their reimbursement and statistics. The SSJ sent a separate mailing offering vaccination in schools. The mailing for girls <16 years of age included a parental consent form. A reminder letter was sent to all eligible girls. An automated electronic reminder via short messaging service and an individual letter were also sent to the eligible girls owning a mobile phone who had received their first injection at the Geneva University Hospital vaccination center.12

Estimation of HPV vaccination coverage of the target population

At the beginning of the Geneva vaccination program in September 2007, 20,541 adolescent girls aged 11–19 years were eligible for vaccination, with a new yearly cohort of approximately 2,400 11-year-old girls. This number was used as the denominator to estimate immunization coverage with two and three doses of vaccine; this yearly denominator was supplied by the Service for Research in Education of the canton of Geneva based on an official government database. To determine the numerator, each service provider transmitted a nominal list of the people who had received their first, second, or third doses of HPV vaccine to the State Medical Office on a quarterly basis. Coverage for these cohorts was measured three times: on December 31, 2009, a year and a half after the program started; on June 30, 2011, after three years; and on June 30, 2012, four years into the program. We conducted statistical analysis using Stata® version 10.0.13 All personal identifiers were removed prior to the analysis.

OUTCOMES

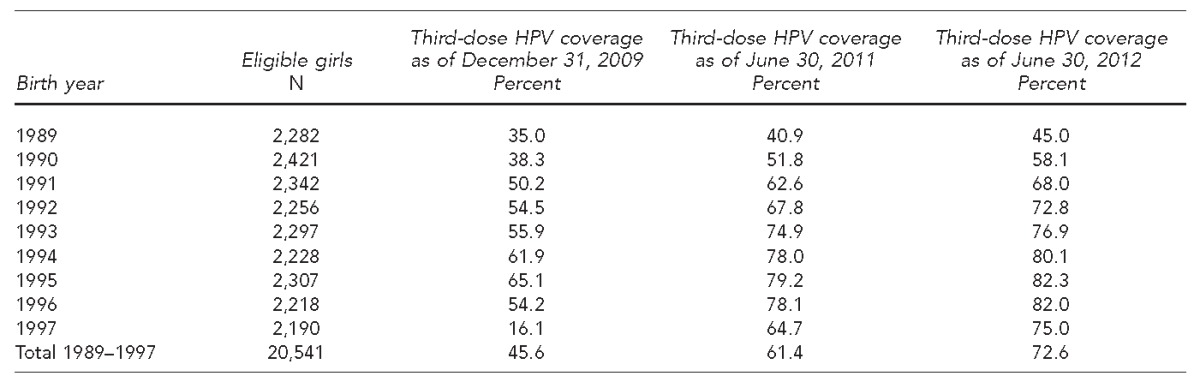

A year and a half into the program, three-dose HPV coverage for the 1989–1997 birth cohort was 45.6% (Table). Coverage had progressed to 61.4% after three years and 72.6% after four years, a 27-percentage-point increase in 2.5 years. Two-dose HPV coverage increased from 47.9% to 63.2% to 74.8% at the 1.5-, 3-, and 4-year marks, an increase of 27 percentage points in 2.5 years for the target population (data not shown). The vast majority of girls who received their second dose also received the third dose, with an average difference of only two points (data not shown). To date, the highest coverage was reached among girls born between 1994 and 1996 (aged 16–18 years at the beginning of the program), and at least 80% of them had received three doses of vaccine four years into the program (Table).

Table.

Evolution of third-dose HPV coverage from December 31, 2009, to June 30, 2012, for adolescent girls born between 1989 and 1997 in Geneva Canton, Switzerland

HPV = human papillomavirus

Service providers covered different age groups. SSJ vaccinated 80% of the 14-year-old girls, 60% of the 13-year-old girls, and <10% of those aged 16–21 years. Medical doctors in private practice vaccinated 50%–70% of the target population except in the 13- to 14-year-old age group. Geneva University Hospital (ad hoc vaccination center) vaccinated about 50% of girls aged 18–19 years and a much lower proportion (5%–15%) of those aged 11–14 years. The proportion of eligible girls who did not get the second and/or third dose after receiving the first dose was similar for all age groups regardless of the service providers, with the exception of the SSJ (data not shown).

LESSONS LEARNED

Within a fairly short period of time, the HPV vaccination program implemented in Geneva has achieved immunization coverage as high as 82% in the main target group. One reason for this success could be related to the opportunity given the target audience to be vaccinated by different providers (e.g., school health service, Geneva University Hospital, and physicians in private practice). Media interest, public promotion of the vaccination program, and direct mailing with free vouchers have also played an important role in the program's success. Although the monitoring system was relatively complex for vaccination providers, it helped to improve coordination and collaboration between the various stakeholders and the State Medical Office. In Geneva, the State Medical Office coordinated the HPV vaccination program, imposing for management purposes a strict registration system for monitoring financial and HPV vaccine flow. This monitoring scheme made it possible to follow trends in vaccination uptake in the target population during the four-year period.

To date, Geneva Canton is the only canton in Switzerland that has published comprehensive, population-based coverage data.12 A first estimation of HPV coverage for the entire Swiss population was conducted in 2013 (Personal communication, Claire Anne Wyler, School Health Service, Geneva, January 2014), indicating a rate of 51% (95% confidence interval 48.4, 52.9) for three doses of vaccine in girls aged 16 years. Unfortunately, many Swiss cantons, especially Geneva Canton, did not participate in this study; as such, comparison with our results was difficult.

If cervical cancer is to be eliminated as a public health problem, increasing and maintaining high HPV vaccination coverage of new cohorts remains the main programmatic challenge. In 19 out of 29 European Union countries that have launched HPV vaccination programs, coverage rates vary widely from only 17% in Luxembourg to 84% in Portugal for three doses. In 2010, of seven countries reporting coverage data, only Portugal and the United Kingdom had full vaccination coverage rates >80% for their target groups.14 In the U.S., vaccination coverage for adolescents aged 13–17 years with two and three doses significantly increased annually for the 2007–2012 period: from 16.9% to 43.4% for two doses and from 5.9% to 33.4% for three doses. However, this coverage rate is still lower than results in Europe or Geneva.15

There is no explanation for the better acceptability of HPV vaccination in Switzerland than in other countries. As for Geneva Canton, there might be less hesitation about immunization compared with other countries. To better understand these differences, further research will be conducted to determine the motivation and reason for nonvaccination in our context.

Vaccination in boys is expected to facilitate the eradication of cervical cancer, reduce transmission of the virus, increase herd immunity, and contribute to the prevention of HPV-associated diseases in both genders. However, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health does not yet recommend HPV vaccination for men. This issue remains important, as more incremental benefits are expected through the inclusion of boys in the vaccine program.16

Limitations

Our study was subject to several limitations. First, we could not follow individuals' vaccination history and use the number of eligible residents, as it was known in cantonal statistics at the beginning of the program, as the denominator of coverage calculation. However, this methodological choice should only have had a marginal impact on the coverage estimate and its trend because the cohort of eligible patients remained fairly stable during this short period of time. Second, not all service providers transmitted the nominal lists of vaccinated people for monitoring. Thus, there was a bias in the evaluation of our coverage.

CONCLUSION

Although estimated HPV vaccination coverage has not yet reached 80% in all eligible age groups, it has been increasing over time and a favorable trend seems to be emerging. Easy and free access to vaccination; well-coordinated delivery services, including school health, public hospitals, and private physicians; and general and individual information played a major role in this program's success. In the future, an important challenge will be determining if this strategy is the best one for maintaining and further increasing coverage with younger cohorts and expanding the target population to young men.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the State Medical Office of Geneva.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berchtold A, Michaud PA, Nardelli-Haefliger D, Suris JC. Vaccination against human papillomavirus in Switzerland: simulation of the impact on infection rates. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Report of the consultation on human papillomavirus vaccines. Geneva: WHO; 2005. Also available from: URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/WHO_IVB_05.16.pdf [cited 2013 May 7] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Judson PL, Habermann EB, Baxter NN, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Trends in the incidence of invasive and in situ vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1018–22. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000210268.57527.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.University of Geneva. Geneva: University of Geneva; 2009. [Cancer in Geneva: incidence, mortality, survey, and prevalance, 2003–2006] Also available from: URL: http://www.unige.ch/medecine/rgt/publicationquadriennale/publication_1970_2006.pdf [cited 2013 Jun 10] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lugarini J, Maddalo F. Results of a vaccination campaign against human papillomavirus in the province of La Spezia, Liguria, Italy, March–December 2008. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:19342. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.39.19342-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petignat P, Bouchardy C, Sauthier P. [Cervical cancer screening: current status and perspectives] Rev Med Suisse. 2006;2:1308–9. 1311–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petignat P, Untiet S, Vassilakos P. How to improve cervical cancer screening in Switzerland? Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13663. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal Office of Public Health. Human papilloma virus (HPV) [cited 2013 Jun 15] Available from: URL: http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00682/00684/03853/index.html?lang=en.

- 9.Tomljenovic L, Spinosa JP, Shaw CA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines as an option for preventing cervical malignancies: (how) effective and safe? Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:1466–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper DM. Currently approved prophylactic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:1663–79. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federal Office of Public Health. Factsheets [cited 2013 Jun 15] Available from: URL: http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/medizin/00682/00685/03212/index.html?lang=en.

- 12.Jeannot E, Sudre P, Chastonay P. HPV vaccination coverage within 3 years of program launching (2008–2011) at Geneva State, Switzerland. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:629–32. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.StataCorp. Stata®: Version 10.0. College Station (TX): StataCorp; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Center of Disease and Control. ECDC guidance on HPV vaccination: focus on reaching all girls. 2012 [cited 2013 Jul 11] Available from: URL: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/press/news/_layouts/forms/News_DispForm.aspx?ID=497&List=8db7286c-fe2d-476c-9133-18ff4cb1b568.

- 15.Stokley S, Curtis CR, Jeyarajah J, Harrington T, Gee J, Markowitz L. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007–2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2013—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(29):591–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crosignani P, De Stefani A, Fara GM, Isidori AM, Lenzi A, Liverani CA, et al. Towards the eradication of HPV infection through universal specific vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:642. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]