Abstract

Type-2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s2) and the acquired cluster of differentiation 4 (CD43)+Th2 and Th17 cells contribute to the pathogenesis of experimental asthma; however, their roles in Ag-driven exacerbation of chronic murine allergic airway diseases remain elusive. Herein, we report that repeated intranasal re-challenges with only OVA Ag were sufficient to trigger airway hyperresponsiveness, prominent eosinophilic inflammation, and significantly increased serum OVA-specific IgG1 and IgE in rested mice that previously developed murine allergic airway diseases. The recall response to repeated OVA inoculation preferentially triggered a further increase of lung OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells, whereas CD4+Th17 and ILC2 cell numbers remained constant. Furthermore, the acquired CD4+Th17 cells in Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice, or innate ILC2s in CD4+T cell-ablated mice, failed to mount an allergic recall response to OVA Ag. After repeated OVA re-challenge or CD4+T cell ablation, the increase or loss of CD4+Th2 cells resulted in an enhanced or reduced IL-13 production by lung ILC2s in response to IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation, respectively. In return, ILC2s enhanced Ag-mediated proliferation of co-cultured CD4+Th2 cells and their cytokine production, and promoted eosinophilic airway inflammation and goblet cell hyperplasia driven by adoptively transferred Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells. Thus, these results suggest that an allergic recall response to recurring Ag exposures preferentially triggers an increase of Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells, which facilitates the collaborative interactions between acquired CD4+Th2 cells and innate ILC2s to drive the exacerbation of a murine allergic airway diseases with an eosinophilic phenotype.

Introduction

In developed countries, exacerbation of allergic asthma often results in significant morbidity (1). The recurrent episodes of allergic asthma are often triggered by repeated allergen exposures that may occur upon a background of chronic allergic inflammation and structural changes (2). Repeated exposures to allergens may mediate the maintenance of a persistent inflammatory process, which often results in an increased severity of chronic allergic asthma (3). It has long been postulated that lung resident CD4+Th2 cells induced after primary allergen exposure are responsible for the exacerbation of allergic asthma after allergen re-exposures (4-6). These Ag-experienced CD4+Th2 effector/memory cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 that mediate the eosinophilic inflammation that defines a major subphenotype of asthma (7-9). The discovery of the CD4+Th17 cell lineage and its function in driving airway neutrophilic inflammation has provided insight into the understanding of the heterogeneity of chronic asthma (10-12). Increased expression of IL17 transcripts was found to be associated with patients with severe asthma (13, 14). In murine models of allergic lung diseases, IL-17 produced by CD4+Th17 or IL-17–producing Th2 cells was also shown to contribute to the exacerbation of experimental allergic asthma (15-17). Although many studies have demonstrated the essential roles of Th2 and Th17 immune responses in the pathogenesis of murine allergic airway diseases, little is known about their relative contributions to the Ag-driven exacerbation of murine allergic airway diseases.

In addition to acquired T helper cell immunity, recent studies identified a novel innate cell lineage, type-2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), as potent Th2 cytokine producers involved in the allergic immune response (18-22). Subsequent studies revealed that ILC2s could develop from common lymphoid progenitors and that their differentiation and maintenance require the transcription factors retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor alpha (ROR-α4) and GATA binding protein 3 (GATA-35) (23-25). Notably, ILC2s lack Ag-specific receptors and express high levels of an array of cytokine receptors, including IL-25R (IL-17RB), IL-33R (ST2), IL-7Rα and IL-2Rα (19, 20). ILC2s can rapidly elicit large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation in the presence of IL-7 and/or IL-2 (19, 26). Indeed, ILC2s were functionally impaired in the Il17rb−/−, St2−/−, or common gamma chain (γc)−/−/Rag2−/− mice, which failed to expel helminthic infection effectively (20, 21). These studies highlight the importance of ILC2s in mediating the protective type-2 immune response against parasitic infection by acting as the early cellular source of Th2 cytokines before the development of acquired T cell immunity.

Accumulating evidence also suggest a critical role of ILC2s in initiating airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR 6) and eosinophilic inflammation. Intranasal papain or IL-33 administration induced robust IL-5 and IL-13 production by adoptively transferred ILC2s that were sufficient to drive airway eosinophilia in common gamma chain (γc)−/−/Rag2−/− recipient mice or AHR in Il13−/− mice (26, 27). Four days after the initial exposure to papain and preceding the peak of T cell response, ILC2-deficient mice reconstituted with ROR-α−/− bone marrow displayed significantly less pulmonary inflammation than ILC2-deficient mice transplanted with wild-type (WT7) bone marrow (24). Although these studies highlight the importance of ILC2s in initiating Th2 inflammation in response to intranasal stimuli, the involvement of ILC2s in driving Ag-induced exacerbation of chronic murine allergic airway diseases have been unclear. Notably, Rag2−/− mice that developed functional ILC2s, but lacked the T cell compartment, also exhibited less severe eosinophilic airway inflammation than WT mice after repeated papain inhalation (28). These findings suggest that both the innate and adaptive branches of type-2 immunity are required for the maximum exacerbation of chronic allergic inflammation induced by response to repeated allergen.

In this report, we examine the immune response of innate ILC2s and OVA-specific CD4+Th2 and Th17 cells during the course of the acute, rest, and recall phases of murine allergic airway diseases. We found that in rested mice that were previously sensitized with allergens, repeated OVA Ag re-challenge preferentially induced the accumulation of lung OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells, not Th17 cells or ILC2s, and that this accumulation was associated with the profound eosinophilic inflammation and significant increase of OVA-specific IgE and IgG1. Although ILC2s are not sufficient to mount an Ag recall response, these cells enhanced the eosinophilic inflammation induced by Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells. Thus, our results suggest that lung-resident, Ag-specific Th2 cells co-operate with ILC2s to drive OVA Ag recall induced exacerbation of murine allergic airway diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

BALB/c mice (Thy1.2+) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA). BALB/c mice (Thy1.1+) (stock number 005443), Stat6−/− mice (stock number 002828), IL-4-GFP reporter (4get) mice (stock number 004190) and DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice (stock number 003303) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. IL-17-GFP reporter mice were purchased from BIOCYTOGEN. Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice were generated by crossing Stat6−/− mice with IL-17-GFP reporter mice. All genetically modified mice used in this study were on the BALB/c background or were backcrossed to BALB/c background for more than 10 generations. All mice were used at 6-9 weeks of age, and all experiments employed age- and gender-matched controls to account for any variations in data sets compared across experiments. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Induction of allergic airway diseases

Mice were intranasally sensitized with 70 μg papain (Calbiochem) or Aspergillus oryzae (Sigma-Aldrich) and in the presence of 43 μg OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) protein in 50 μl saline (mixed immediately before administration) or 50 μl saline only every other day for total of 6 times and then rested for 7 days before intranasal administration of OVA protein (100 μg in 50 μl saline) alone, 70 μg papain in 50 μl saline or 50 μl saline only every other day for a total of additional 6 times. Potential endotoxin contamination was removed from OVA by endotoxin-removing gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mice were sacrificed 1 day after the last Ag challenge.

Assessment of airway inflammation by bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cellular analysis and histology

Lungs were washed with 1 ml PBS, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF8) was collected, and total cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Slides were prepared by cytocentrifugation and stained with Fisher HealthCare protocol Hema 3 solutions. BALF cell differential counts were determined using morphologic criteria under a light microscope with evaluation of more than 150 cells per slide. In some experiments, lung tissue was fixed with 10% formalin solution and then submitted to the Pathology Research Core at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center for H&E and periodic acid-Schiff staining.

Assessment of airway hyperresponsiveness

AHR was studied in anesthetized mice 1 day after the last Ag challenge. Anesthesia was delivered by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylaxine/acepromazine (4:1:1) solution (0.2 ml/animal). Changes in airway resistance to methacholine (acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were assessed as previously described (29). Briefly, a tracheostomy was performed, and the mouse was connected to a flexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, QC, Canada). Airway resistance was measured after nebulization of PBS (baseline) and then increasing doses of methacholine (25, 50, and 100 mg/ml).

Isolation of lung cells and flow cytometry

Lungs were dissected and forced through a 40-μm cell strainer to make single-cell suspensions and then analyzed by flow cytometry. In some experiments, lung cells were first enriched for CD11b- and CD19-negative cells by magnetic anti-CD11b and anti-CD19 microbeads and then separated into 2 tubes for staining: T cells were stained with PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD3e (145-2C11), Pacific Blue–conjugated anti-CD4 (RM4-5 or RM4-4), PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated monoclonal antibodies against lineage (Lin 9) markers (NK1.1[PK136], CD11b[M1/70], CD11c[HL3], CD8[53-6.7], B220[RA3-6B2], Gr-1[RB6-8C5], and CD335[NKP46, 29A1.4]), allophycocyanin-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD62L, and/or allophycocyanin–conjugated anti-DO11.10 TCR(KJ-126); ILC2s were stained with allophycocyanin–conjugated rat anti-human/mouse IL-17RB mAb (clone SS13B, a gift from Dr. Kenji Izuhara, Saga Medical School, Japan), PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated mAbs against Lin markers (NK1.1[PK136], CD11b[M1/70], CD11c[HL3], CD3e[145-2C11], CD4[RM4-5], CD8[53-6.7], B220[RA3-6B2], Gr-1[RB6-8C5], and CD335[NKP46, 29A1.4]), PE-conjugated anti-ICOS(7E.17G9), allophycocyanin-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD25(PC61), PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD127(A7R34), V500-conjugated anti-ScaI(Ly6A/E, D7), and biotinylated anti-T1/ST2(DJ8) Abs and then further stained with Brilliant Violet 421–labeled Streptavidin (Biolegend) before analyses with a FACSCanton II (BD Bioscience) or cell sorting with a FACSAria II (BD Bioscience) maintained by the Research Flow Cytometry Core in the Division of Rheumatology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

ELISA

Single-cell suspensions were made from lungs of mice 1 day after the last Ag challenge, 3.0×105 cells were stimulated with medium only, OVA (10 μg/ml), or IL-25 (10 ng/ml) plus IL-33 (10 ng/ml), and in some experiments, anti-mIL-2 mAb (Clone: JES6-1A12, 10μg/ml) were added for 3 days. Collected supernatants were assessed by ELISA for IL-5 (R&D Systems), IL-13 (Antigenix America), IL-4, IL-17 and IFN-γ (BD Biosciences).

Serum OVA-specific IgE and OVA-specific IgG1 were measured using an OVA-IgE ELISA kit (MD Bioproducts) or OVA-IgG1 ELISA kit (Alpha Diagnostic), respectively.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

RNA from sorted cell populations was isolated with an RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA templates were synthesized with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (BioRad). Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed with SYBR Green Chemistry (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI Prism 7900 detection system using previously described primer sets (30, 31). Expression levels of target genes were normalized to endogenous Gapdh transcript levels, and relative quantification of samples was compared to the expression level of indicated genes in naïve CD4+T cells isolated from naïve BALB/c mice as the baseline.

CD4+T cell depletion

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-CD4 mAb (clone GK1.5, 300 μg/mouse in 500 μl PBS; Bio-X cell) or Rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) 24 hours before the first and the fourth OVA re-challenge.

Co-culture and adoptive transfer of OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells and ILC2s

OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells were generated as described (15). DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were first immunized intraperitoneally with 100 μg of OVA in 2 mg of aluminum hydroxide (Thermo Fisher Scientific). CD4+T cells were positively selected from splenocytes and cultured with APCs (irradiated CD4− cells) pulsed with 10 μM OVA323-339 peptide in the presence of anti-IFN-γ mAb (20 μg/ml, XMG 1.2) and IL-4 (10 ng/ml, Peprotech) for 7 days.

ILC2s were induced as previously described (20). BALB/c mice were injected with 400 ng per dose of recombinant mouse IL-25 (R&D Systems) in PBS daily for total of 4 days. Mesenteric lymph nodes were collected and pooled together for single-cell suspensions. After staining the cells with purified rat anti-mouse CD19 (1D3), rat anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70), rat anti-mouse CD8 (53.6.72), and rat anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5) mAbs (Bio-X cell) followed by goat anti-rat microbead staining, cells were enriched for CD19−, CD11b−, CD8−, and CD4− cells using MACS columns. Enriched CD19−, CD11b−, CD8−, and CD4− cells were stained with ILC2s markers as described above, and IL-17RB+ST2+Lin− cells were sorted out as ILC2s. Purified ILC2s were assessed for surface MHC class II expression with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse MHCII (NIMR-4) by flow cytometry. 5.0×104 irradiated splenocytes (APC) depleted of CD4+T cells or purified ILC2s were cultured with 10 μg/ml DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes) at 4°C or 37°C for 3h, extensively washed and fluorescence assessed by flow cytometry.

To examine the interactions between CD4+Th2 cells and ILC2s in vitro, OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells (1.0×105), ILC2s (5.0×104), or OVA-specific Th2 cells (1.0×105) co-cultured with ILC2s (5.0×104) pulsed with 1 μg/ml OVA323-339 peptide for 3 days before the analysis of intracellular cytokine production by flow cytometry or the collections of supernatants for the measurements of cytokine production using ELISA. In some experiments, OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells were labeled with CellTrace Violet (Molecular Probes) before co-culture with or without OVA323-339 peptide-pulsed ILC2s for the analysis of proliferation. For in vivo experiments, Thy1.2+BALB/c mice were i.v. injected with OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells (1.0×106), ILC2s (5.0×105), or both of cell types one day before intranasal challenge with OVA protein (100 μg) for 3 consecutive days. In some experiments, congenic Thy1.1+BALB/c mice were used and treated with 250μg anti-Thy1.1 mAb (clone 19E12, Bio-X cell) intraperitoneally on the day of and 2 days after cell transfer. Total and differential cell counts in BALF were evaluated 24 hours after the last OVA challenge. The left lung was fixed with 10% formalin solution and then submitted to the Pathology Research Core at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center for H&E staining and periodic acid-Schiff staining. The rest of the lung tissue was forced through 40-μm cell strainers to make single-cell suspensions and then stimulated with OVA protein (10 μg/ml) or medium as a control for 3 days. Secreted cytokines in the collected supernatants were assessed by ELISA.

Results

Repeated Ag re-challenges preferentially induce eosinophilic airway disease

To study CD4+ T helper cell response to recurrent Ag exposures in the context of allergic inflammation, we first challenged mice 6 times intranasally with OVA Ag plus protease allergens papain to induce an acute phase of pulmonary allergic inflammation. After 7 days of rest, sensitized mice were re-challenged intranasally with OVA or saline only for an additional 6 times prior to subsequent analysis of the pulmonary CD4+ T helper cell response (protocol diagramed in Fig. 1A). Compared to naïve mice, the first episode of repeated intranasal challenge triggered substantial infiltration of the airway by inflammatory cells that included predominantly eosinophils (>40%), neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, as shown in the total and differential cell counts of the BALF (Fig. 1B and data not shown). These sensitized mice produced detectable titers of serum OVA-specific IgE (>1.0 μg/ml) and IgG1 (>1.0×107 U/ml) (Fig. 1C), displayed pathological changes in the lung as evidenced by their prominent mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia, and developed AHR as previously reported (data not shown) (15, 32). Thus, similar to previous studies of a murine allergic airway diseases (15, 32), the first episode of repeated intranasal challenge is sufficient to promptly induce the development of murine allergic airway diseases, termed the ‘acute phase’. After 7 days of rest, much fewer eosinophils and neutrophils were retained in the airway, and mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia were reduced (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Notably, these rested mice produced similar amounts of OVA-specific IgE and IgG1 as mice in the acute phase of murine allergic airway diseases (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the Ag OVA-specific Th2 immune response persists in the rested mice, despite the resolution of pulmonary inflammation. Indeed, re-exposure only to OVA Ag rapidly induced a significant increase in the eosinophil, but not neutrophil, infiltration of the airway, which is positively associated with the number of OVA Ag re-challenges (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, these re-challenged mice also developed a robust humoral response against OVA Ag as evidenced by their elevated serum titers of OVA-specific IgE (>30 μg/ml) and IgG1 (>5.0×108 U/ml) (Fig. 1C). Consequently, repeated re-challenge with OVA Ag only, but not saline or BSA, induced these rested mice to re-develop severe AHR and prominent mucus production and goblet hyperplasia, termed the ‘recall phase’ of murine allergic airway diseases (Fig.1D and E). Together, these data suggest that intranasal OVA re-challenge preferentially triggers airway eosinophilic inflammation and further increases the levels of Ag-specific serum IgE and IgG1 in rested mice that previously developed pulmonary allergic inflammation.

FIGURE 1.

Repeated OVA Ag re-challenges preferentially induce eosinophilic murine allergic airway diseases. (A) Mice were exposed to OVA and papain (tick marks) every other day for total of 6 times (acute phase, days 1-11), rested for 7 days (rest phase, days 12-18), and re-challenged with OVA or saline alone every other day (tick marks) for a total of 6 times (recall phase, days 19-29). Mice were sacrificed and indicated samples were collected for analysis at selected time points (arrows, day 0, 12, 18, 19, 23, and 29). (B-C) BALF (B) and serum (C) samples from naïve mice or mice sacrificed one day after indicated phase, or times of re-challenges were collected for the measurements of BAL total, eosinophil, or neutrophil cell numbers (B) and titers of serum OVA Ag-specific IgE and IgG1 (C). (D-E) Mice that experienced the acute and rest phase, were then re-challenged with saline, BSA, or OVA every other day for total six times at the recall phase. One day after the last re-challenge, their AHR were measured by flexivent (D) and lung sections were analyzed by H&E and periodic acid-Schiff staining (E). Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4-6 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. Scale bars are 100 μm. ***p < 0.001. OVA-, OVA Ag-specific; NS, not significant.

Repeated Ag re-exposures preferentially enhance CD4+Th2 immune response

We next examined the frequency of CD4+T cell compartments before and after repeated OVA Ag re-exposures in IL-4-GFP and IL-17-GFP reporter mice. While very few lung GFP+CD4+T cells could be detected in naive reporter mice (< 1% of total CD4+T cells), the initial set of OVA Ag plus papain challenges, not saline only, induced similar percentages or numbers of CD4+Th2 (15.1 ± 1.2% or 127.8 ± 5.7×103, mean ± SEM) or CD4+Th17 (14.8 ± 1.1% or 140.6 ± 7.8×103, mean ± SEM) cells in the lung of challenged IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice, respectively (Fig. 2A and B and Supplemental Fig. 1B). We confirmed that purified CD4+CD62L−GFP+ cells from challenged IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice produced indicated Th2 or Th17 cytokines, respectively, demonstrating that the GFP expression by these reporter mice faithfully marked indicated T-cell immune response (Supplemental Fig. 1A). After 7 days of rest, the numbers of both CD4+Th cell subsets (67.2 ± 3.9×103 vs. 74.8 ± 5.6×103, Th2 vs. Th17, mean±SEM) decreased significantly (Fig. 2A and B). Notably, repeated OVA Ag re-exposures triggered a substantial increase in lung resident CD4+Th2 cells in both percentage (37.1 ± 1.3%, mean± SEM) and number (341.2 ± 15.5×103, mean± SEM), which were much higher than those in the lungs of mice at the acute phase (Fig. 2A and B). We also observed increased infiltration of CD4+Th17 cells; however, their percentage (15.4 ± 1.1%, mean± SEM) and number (165.7 ± 6.7×103, mean± SEM) appeared similar to those at the acute phase (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly, repeated papain Ag re-exposures also preferentially triggered a significant increase of CD4+Th2 number (227.6 ± 21.6×103, mean± SEM), not CD4+Th17 cells (144.0 ± 3.2×103, mean± SEM), compared to those in the lungs of mice at the acute phase (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Taking the advantage of the KJ1-26 mAb that reacts with TCRs that recognize the MHC class II-restricted OVA323-339 peptide specifically, subsequent analysis further revealed that the percentage and number of lung KJ1-26+CD4+CD62L−IL-4+Th2 cells were significantly increased from the acute phase (0.011 ± 0.005% and 192.7 ± 64.2, mean ± SEM) after repeated OVA Ag re-challenge (0.063 ± 0.006% and 783.3 ± 121.0, mean ± SEM) (Fig. 2C and D). In contrast, repeated OVA Ag re-challenge failed to induce an increase in percentage and number of KJ1-26+CD4+CD62L−IL-17+Th17 cells (0.021 ± 0.008% and 168.3 ± 49.9 at the acute phase; 0.031 ± 0.003% and 264.0 ± 54.8 at the recall phase) (Fig. 2C and D). In concert with these observations, ex vivo OVA or papain Ag re-stimulation induced lung CD4+T cells to produce significantly higher amounts of the Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 at the recall phase than at the rest or acute phase (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. 1C), whereas the amounts of IL-17 and IFN-γ produced by lung CD4+T cells were comparable between the acute and recall phase (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. 1C). These results suggest that lung resident CD4+Th2 cells are the primary cells responsible for mounting an Ag recall response and that the percentage of Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells, not Th17 cells, increased significantly after Ag re-exposure in rested mice that had previously developed allergic airway disease.

FIGURE 2.

Repeated OVA Ag re-challenges preferentially induce an increased Ag-specific CD4+Th2 immune response. (A-B) Naïve, or 1 day (acute) or 7 days (rest) after 6 OVA and papain sensitizations, or 1 day after 6 OVA re-challenges (recall), (A) expression of IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP and CD62L by CD4+T cells (gated on Lin−CD3+CD4+ cells) from lungs of IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice, respectively, were examined by flow cytometry; (B) Frequency (GFP+CD62L− cells within total CD4+T cells) and number of lung CD4+GFP+CD62L− Th2 or Th17 cells in IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice, respectively, are shown for indicated time points. (C-D) Naïve (D), or, 1 day after 6 OVA and papain sensitizations (acute) or 1 day after 6 OVA re-challenges (recall) (C-D), (C) Flow cytometry of KJ1-26+ cells and their expression of IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP in the lung from IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice (gated on Lin−CD3+CD4+CD62L− cells), respectively, and (D) frequency (GFP+KJ1-26+ cells within total CD4+T cells) and number of lung GFP+KJ1-26+CD4+Th2 or Th17 cells in IL-4-GFP or IL-17-GFP reporter mice, respectively. (E) Lung cells from mice at indicated phases of murine allergic airway diseases were re-stimulated ex vivo with medium (Med) or OVA for 3 days; the amounts of indicated cytokines secreted into the supernatant were examined using ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

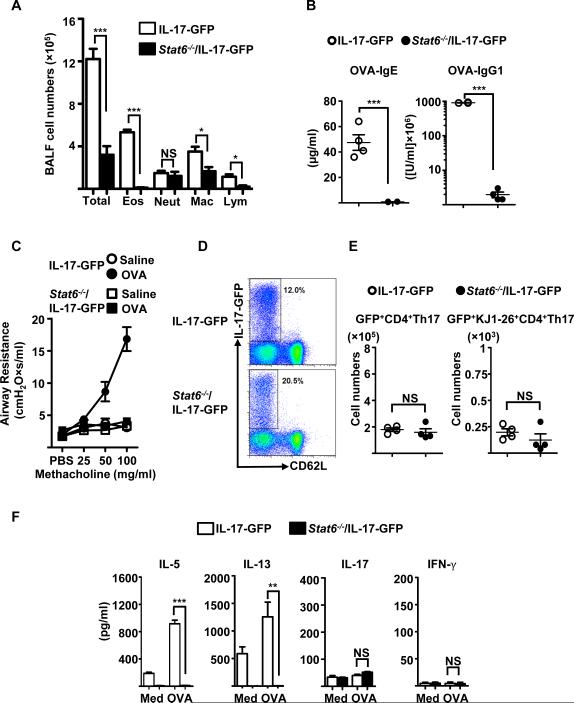

Th17 cells are not sufficient to mount an Ag-induced recall allergic response in the absence of the Th2 cell compartment

Allergen-specific CD4+Th2 cells that reside in the lung after primary allergen exposure have been suggested to be responsible for the exacerbation of allergic asthma after allergen re-exposures (4, 5). To evaluate the essential role of lung resident Th2 cells in mediating OVA recall–induced murine allergic airway diseases, we examined mice deficient in STAT-6, a key transcription factor for Th2 but not Th17 cell differentiation, that were further crossed with IL-17-GFP reporter mice (Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP) (33, 34). Indeed, compared to IL-17-GFP WT mice, Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice lacking the CD4+Th2 cell compartment exhibited substantially reduced infiltration by inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes but not neutrophils, in the airway after repeated intranasal OVA Ag re-challenge (Fig. 3A). Notably, repeated OVA Ag re-challenge failed to induce robust increases of serum OVA Ag-specific IgE and OVA Ag-specific IgG1, as well as AHR, in the Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice (Fig. 3B and C). In concert with the observation of normal neutrophil recruitment, the number of infiltrated CD4+Th17 cells (159.3 ± 26.9×103, mean ± SEM) in the Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice was comparable to that (173.1 ± 9.5×103, mean ± SEM) in IL-17-GFP WT mice (Fig. 3D and E). Additionally, we did not observe an increase of the OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th17 cell recall response to repeated OVA Ag re-challenge (Fig. 3E). Consequently, very low levels of IL-5 and IL-13 cytokines were produced by OVA Ag–stimulated lung cells of Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice ex vivo, whereas their IL-17 and IFN-γ production were similar to those in the IL-17-GFP WT mice (Fig. 3F). Collectively, these results suggest that the CD4+Th2, not Th17, cell compartment is required for mounting the Ag recall allergic immune response.

FIGURE 3.

Th17 cells are not sufficient to mount OVA antigen re-challenge induced eosinophilic murine allergic airway diseases. One day after the last OVA re-challenge, (A) total and differential cell counts in BALF, (B) serum OVA-specific IgE and IgG1 levels (OVA-IgE, OVA-IgG1), and (C) airway resistance to increasing doses of methacholine were measured in WT IL-17-GFP or Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP reporter mice; (D) expression of IL-17-GFP and CD62L by CD4+T cells (gated on Lin−CD3+CD4+ cells) from lungs of WT IL-17-GFP or Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP reporter mice were examined by flow cytometry; (E) numbers of GFP+CD62L−CD4+Th17 cells and GFP+KJ1-26+CD4+Th17 cells in lung from WT IL-17-GFP or Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP reporter mice. (F) Lung cells were re-stimulated with medium (Med) or OVA for 3 days, and the indicated cytokines in supernatant were examined using ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01;***p < 0.001. Eos, eosinophils; Lym, lymophocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neut, neutrophils; NS, not significant; OVA-, OVA Ag-specific.

Repeated OVA Ag re-challenge promotes IL-13 production by ILC2s

Recent studies demonstrated a pivotal role of ILC2s in the initiation of allergic inflammation (26, 27, 35); however, their frequency and function at the acute and recall phase of murine allergic airway diseases have not been addressed. Multicolor flow cytometry analysis identified a dominant cell population that expressed ST2 and IL-17RB but not known cell lineage markers (Lin−) in the lung of mice sensitized with papain plus OVA (Fig. 4A). These Lin−ST2+IL-17RB+ cells also expressed IL-2Rα (CD25), IL-7Rα (CD127), ICOS, and Sca-1, the signature markers of ILC2s (19, 20, 36) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, purified Lin−ST2+IL-17RB+ cells from the lung of mice with allergic airway disease expressed high levels of the transcription factor Rora, Gata3, Id2, Il5, Il13, and Amphiregulin transcripts (Fig. 4B). Thus, these Lin−ST2+IL-17RB+ cells detected in our murine model of allergic lung diseases are the recently described ILC2s (36). Next, we examined the percentage and number of these lung resident ILC2s at the acute, resting, and recall phase of allergic lung diseases and compared their capability to produce the Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 plus IL-33 stimulation ex vivo. Although very few ILC2s (frequency 0.5% ± 0.2%, number 3.3×103 ± 1.3×103, mean± SEM) could be detected in the lung of naïve or saline-challenged mice, the initial intranasal OVA plus papain challenge triggered a significant increase in their percentage (2.5% ± 0.3%, mean ± SEM) and number (64.6×103 ± 4.2×103, mean ± SEM) (Fig. 4C and data not shown). Intriguingly, the percentage (2.2% ± 0.3%, mean ± SEM) and number (63.7×103 ± 1.8×103, mean ± SEM) of ILC2s persisted in the lungs of challenged mice after 7 days of rest (Fig. 4C), although the pulmonary inflammation had largely resolved (Fig. 1B). Notably, compared to their frequency at the acute phase, repeated saline or OVA Ag re-challenge did not further increase lung ILC2 percentage (2.5% ± 0.4%, mean ± SEM) or number (66.8×103 ± 3.4×103, mean ± SEM) at the recall phase (Fig. 4C and data not shown). Treatment with IL-25 plus IL-33 induced ILC2s within lung homogenates from mice at each phase of allergic airway disease to produce comparable amounts of IL-5 (Fig. 4D). Intriguingly, although their numbers remained constant, ILC2s from mice at the recall phase, which developed a significantly increased number of lung CD4+Th2 cells, produced a substantially larger amount of IL-13 than cells within the lung of mice after the acute or rest phase after IL-25 and IL-33 or PMA/ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 4D and E). The increased IL-13 production by lung cells at the recall phase was not primarily contributed by the increased CD4+Th2 cells that also expressed surface ST2 (data not shown), because these CD4+Th2 cells produced 100-fold less amount of IL-13 than that by ILC2s upon IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 2A). These results suggest that, although ILC2 frequency remains constant in the lung of mice during the development of chronic murine allergic airway diseases, their capability of producing IL-13 increases significantly and is positively associated with the number of lung CD4+Th2 cells at the recall phase.

FIGURE 4.

Repeated OVA Ag re-challenge promotes IL-13 production by ILC2s. (A) Cell surface marker expression (CD25, CD127, ICOS, Sca-1) of Lin− ST2+IL-17RB+ cells in the lung 1 day after 6 OVA and papain sensitizations (acute phase). (B) Expression of indicated transcription factor and cytokine genes by purified lung ILC2s (Lin−ST2+IL-17RB+) and CD4+Th2 cells (Lin−CD3+CD62L−GFP+ cells in IL-4-GFP reporter mice), in vitro–generated bone marrow–derived mast cells (BMMCs) and purified spleen eosinophils, neutrophils, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs), B cells, and CD8 T cells was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR using primers referenced in the methods. (C) Frequency (Lin−ST-2+IL-17RB+ cells within total mononuclear cells) and number of lung ILC2s from naïve mice or mice sacrificed 1 day (acute phase) or 7 days (rest phase) after 6 OVA and papain sensitizations or 1 day after 6 OVA re-challenges (recall phase). (D) Total lung cells from mice at indicated time points were stimulated with medium (Med) or IL-25 plus IL-33 for 3 days, and indicated cytokines in the supernatants were analyzed using ELISA. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of intracellular IL-13 production by purified ILC2s (Lin−CD3−CD4−ST2+IL-17RB+ cells) from the lung of mice sacrificed at indicated phases of murine allergic airway diseases. Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. NS, not significant.

ILC2s failed to mount OVA Ag recall response in mice ablated of CD4+ T cells

ILC2s were shown to initiate the early phase of the type-2 immune response against parasitic infection and trigger the allergic immune response (20, 26). To study whether these cells alone can trigger an allergic response in the inflamed lung at the recall phase of allergic lung diseases, we injected anti-CD4 mAb intraperitoneally to deplete CD4+T cells 1 day before the first and fourth OVA Ag re-challenges (Fig. 5A). Indeed, anti-CD4 mAb treatments resulted in a significant reduction in the percentage and numbers of CD4+Th2 cells but not ILC2s in the lung of OVA Ag re-challenged mice (Fig. 5B). Consequently, OVA-induced IL-5 and IL-13 production by Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells in the lung of anti-CD4 mAb–treated mice were significantly less than those of isotype mAb–treated mice. Intriguingly, although ILC2s remaining intact after the loss of lung CD4+T cells (Fig. 5B), these cells responded poorly to IL-25/IL-33 stimulation and produced substantially less amount of IL-13, but not IL-5, IFN-γ, or IL-17, than that by ILC2s of isotype mAb-treated mice (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, despite of comparable frequency or numbers between Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice that lacked CD4+Th2 cell compartment and IL-17-GFP WT reporter mice at both acute and recall phase (Supplemental Fig. 2B), ILC2s in the lung of re-challenged Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice were less capable of producing IL-13 than those in re-challenged IL-17-GFP WT reporter mice in response to IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation ex vivo (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Additionally, anti-IL-2 mAb treatments abrogated the enhanced IL-13 production by ILC2 in the lung of re-challenged IL-17-GFP WT reporter mice in response to IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation ex vivo (Supplemental Fig. 2D). Thereby, repeated OVA Ag re-challenge failed to induce a significant increase in inflammatory cell infiltrations, particularly eosinophils in the BALF, or their serum OVA Ag-specific IgE and OVA Ag-specific IgG1 levels in the mice ablated of CD4+T cells or deficient of Stat6 (Fig. 3A, B, 5D, and E). Furthermore, histological examination showed that these anti-CD4 mAb–treated or Stat6-deficient mice exhibited attenuated peribronchial inflammation and goblet cell hyperplasia (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that ILC2s in the inflamed lung were not sufficient to mediate allergic immune response against repetitive OVA re-challenges in mice lacking CD4+Th2 cell compartment, which can not only mount antigen recall response, but also enhance ILC2 function in their IL-13 production, possibly via their IL-2 production.

FIGURE 5.

ILC2s failed to mount an OVA Ag recall response in mice ablated of CD4+T cells. (A) IL-4-GFP reporter mice were exposed to OVA and papain every other day for total of 6 times during the acute phase, rested for 7 days, and then re-challenged with OVA alone every other day for a total of 6 times during the recall phase. Anti-CD4 or isotype control mAbs were intraperitoneally injected into mice 1 day before the first (day 17) and 1 day before the fourth OVA re-challenges (day 23). Mice were sacrificed 1 day after the last OVA re-challenge when samples were collected for analysis. (B) Frequency and numbers of CD4+Th2 (Lin−CD3+CD62LGFP+) and ILC2s (Lin−CD3−CD4−ST2+IL-17RB+ cells) in the lung of mice treated with indicated mAbs were analyzed 1 day after the last OVA re-challenge. (C) Lung cells were re-stimulated with medium (Med), OVA, or IL-25 plus IL-33 for 3 days, and the indicated cytokines in supernatant were examined using ELISA. (D) Total and differential cell counts in BALF. (E) Serum OVA-IgE and IgG1 levels were measured using ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01;***p < 0.001. Eos, eosinophils; Lym, lymophocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neut, neutrophils; NS, not significant; OVA-, OVA Ag-specific.

ILC2s facilitate antigen-specific Th2 cell–driven allergic airway inflammation by enhancing type 2 cytokine production

Recent studies suggest that ILC2s may have the capacity to modulate CD4+T cell differentiation (37). To address whether ILC2s can augment an Ag-specific Th2 immune response, we examined Th2 cytokine production by in vitro–generated OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells co-cultured with or without purified ILC2s in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Consistent with recent reports (37), ILC2s were found to express detectable surface MHCII and had the potential to process OVA antigen, thus inducing a moderate level of OVA specific Th2 cell proliferation (Supplemental Fig. 3B, C and D). Furthermore, co-cultured ILC2s pulsed with OVA323-339 peptide induced OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells to produce significantly larger amounts of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, not IFN-γ production, than those produced by OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells or ILC2s alone stimulated with OVA323-339 peptide ex vivo (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Fig. 3E). Conversely, these activated OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells also enhanced the function of co-cultured ILC2s in producing IL-13 cytokine as revealed by intracellular cytokine staining (Supplemental Fig. 3E). To demonstrate whether ILC2s can enhance an Ag-specific Th2 cell immune response in vivo, allergic responses exhibited by mice that were adoptively transferred with ILC2s alone, OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells with or without ILC2s were examined and compared after repeated Ag challenge. One day after a regimen of three OVA Ag inhalation challenges, the number of infiltrated eosinophils, but not neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, in the airway of mice transferred with both OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells and ILC2s were significantly higher than those in mice transferred with OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells alone or ILC2s alone (Fig. 6B). Correspondingly, mice given both OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells and ILC2s exhibited much more pronounced mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia compared to mice given OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells or ILC2s alone (Fig. 6C). To further confirm that donor-derived ILC2s indeed infiltrated into lung and facilitated OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cell-mediated airway inflammation, congenic Thy1.1+ mice were treated with anti-Thy1.1 mAb to deplete endogenous ILC2s before adoptive transfer with Thy1.2+ cells. Consistently, the numbers of infiltrated inflammatory cells in the airway of anti-Thy1.1 mAb-treated congenic Thy1.1+ mice that were later transferred with both OVA Ag-specific Thy1.2+CD4+Th2 cells and Thy1.2+ILC2s were significantly higher than those in mice received Thy1.2+CD4+Th2 cells alone (Supplemental Fig. 4A-C). In agreement with the observations from the in vitro co-culture assay, the lung cells from mice transferred with both cell types produced much greater amounts of IL-5 and IL-13, but not IL-17 and IFN-γ, after ex vivo OVA protein re-stimulation than lung cells from mice transferred with only Th2 cells or only ILC2s (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these results suggest that innate ILC2s may facilitate Ag-driven re-activation of lung-resident Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells, which in return, promote ILC2 function to produce increased IL-13 cytokine during the Ag recall response.

FIGURE 6.

ILC2s facilitate Ag-specific Th2 cell–driven allergic airway inflammation by enhancing Ag-driven type 2 cytokine production. (A) In vitro–generated OVA-specific Th2 cells, ILC2s, and a combination of OVA-specific Th2 cells and ILC2s were stimulated with OVA323-339 peptide for 3 days; the indicated cytokines in the supernatant were examined using ELISA. (B-D) BALB/c mice were injected i.v. with in vitro–generated OVA-specific Th2 cells, ILC2s, and a combination of OVA-specific Th2 and ILC2s and were challenged intranasally 24 hours later with OVA alone for 3 consecutive days. One day after the last OVA challenge, (B) total and differential cell numbers in BALF were counted, (C) histology of lung sections were examined by H&E and periodic acid-Schiff staining, and (D) lung cells from mice in the indicated groups were re-stimulated with OVA ex vivo for 3 days, and cytokines in the supernatant were examined using ELISA. Data represent one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars denote mean ± SEM. Scale bars are 100 μm. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Eos, eosinophils; Lym, lymophocytes; Mac, macrophages; Neut, neutrophils; NS, not significant.

Discussion

Allergic asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease of the airway. A subgroup of patients with severe asthma often has persistent symptoms and frequent exacerbations, leading to poor disease control and considerable morbidity (1, 38-40). Accumulating clinical evidence suggests that airway eosinophilic inflammation is associated with a subphenotype of asthma that is prone to become exacerbated (41-45); however, the underlying immunological mechanisms that preferentially drive the eosinophilic phenotype of severe asthma remain elusive. In this study, we established a murine model of chronic allergic lung diseases with prominent airway eosinophilic inflammation. We observed that the increase of airway eosinophils was positively associated with the number of repeated intranasal OVA Ag re-challenges, which preferentially drive the OVA Ag-specific humoral and cellular Th2 immune response. Although both OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 and Th17 cells were induced in the lungs of mice that developed acute allergic airway disease, repeated Ag re-challenge preferentially drove the increase of lung OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2, not CD4+Th17, cell numbers. Notably, the increased number of lung CD4+Th2 cells resulted in enhanced IL-13 production by lung ILC2s in response to IL-25 and IL-33 stimulation. Reciprocally, ILC2s could facilitate CD4+Th2 cells to mediate the exacerbation of allergic lung diseases by promoting Ag-specific type 2 cytokine production.

Several animal studies have demonstrated that both CD4+Th2 and Th17 immune responses can occur concomitantly in the lung after aeroallergen exposures and have suggested their roles in driving the heterogeneity and severity of allergic airway disease (15, 16, 46, 47). However, few studies explore the frequency of an Ag-specific CD4+Th2 and Th17 recall response and the relative contributions of Th2 and Th17 cells in the Ag-driven exacerbation of murine allergic airway diseases. Similar to previous observations (48), we showed that the presence of the protease allergens papain or Aspergillus oryzae facilitated the development of lung CD4+Th2 and Th17 immune responses to repeated intranasal OVA Ag challenge and resulted in allergic inflammation in the airway. Intriguingly, after 7 days of rest and the resolution of airway inflammation, repeated intranasal OVA Ag re-challenges alone were sufficient to drive the exacerbation of murine allergic lung diseases with prominent airway eosinophilia in mice that previously experienced airway inflammation. Notably, we found that the number of OVA Ag re-challenges is positively associated with the number of airway eosinophils and that re-exposure to OVA Ag induced a significant increase of lung OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 immune response but not CD4+Th17 immune response. Furthermore, Stat6−/−/IL-17-GFP mice, which lack the Th2 immune compartment, did not exhibit exacerbation after repeated OVA Ag re-challenges, despite their OVA Ag-specific Th17 cell immune response developing normally. Thus, our findings suggest that inhaled allergens may preferentially induce the expansion of lung-resident, Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells, not Th17 cells, supporting the notion that the Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells are the primary cell type responsible for mounting the Ag recall response during allergic inflammation. Similar to our observations, another study demonstrated that OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells induced by inhaled OVA and lipid Ags can recirculate and seed in the lung of a parabiotic partner to mount an OVA Ag-specific Th2 immune response and drive airway allergic inflammation (49). The underlying mechanisms that preferentially mediate the increase of OVA Ag-specific CD4+Th2 immune response after repeated OVA Ag re-challenge are currently unclear. Whether the OX40 ligand-expressing pulmonary dendritic cells (DCs) endowed by thymic stromal lymphopoietin protein (TSLP10) or pulmonary Th2-permissive microenvironment play a critical role in determining the Ag-specific allergic immune response remains to be addressed (50).

The ILC2, a new member of the innate lymphoid cell lineage, was recently identified in a search for non-B/non-T cells that respond to IL-25 stimulation by initiating type-2 immune responses against parasitic infection or driving acute airway inflammation (18-20, 51, 52). Systemic administration of IL-25 or IL-33 cytokine in mice is sufficient to trigger a substantial influx of ILC2s into the peripheral lymphoid tissues and to activate these cells to produce large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 that initiate acute allergic inflammation in the absence of Ags and prior to the development of adaptive immunity (19-21, 51, 53). However, the frequency and function of ILC2s during the manifestations of chronic allergic disorders driven by the adaptive immunity after prolonged allergen exposures have not been addressed. In our murine model of chronic allergic lung diseases, we observed that after the lung infiltration triggered by the initial allergen exposures during the acute phase, the number of lung ILC2s remained constant during the resting and recall phases, regardless of the number of Ag re-challenges or number of lung-resident CD4+Th2 cells. Indeed, ablation of CD4+T cells in mice that developed acute allergic airway disease failed to affect ILC2s frequency after repetitive OVA Ag re-challenge. Notably, the function of lung ILC2s to produce IL-13 in response to IL-25/IL-33 stimulation ex vivo correlated positively with the number of lung CD4+Th2 cells after repeated OVA Ag re-challenge. These intriguingly findings suggest that the lung ILC2s function may be regulated by environmental cues induced by the acquired CD4+Th2 cell compartment and are in concert with a recent finding showing that although ILC2s constitutively secrete IL-5, their capability to produce IL-13 depends on allergic inflammation (54). The molecular mechanisms underlying how Th2 cells might influence the function of ILC2s are currently unclear. However, IL-2 from CD4+T cells has been suggested to be a key factor in this process (37, 55). Together, these results suggest that the frequency and number of ILC2s are sustained after mice develop allergic airway disease regardless of the inflammatory status in the lung and that the number of CD4+Th2 cells correlates positively with their IL-13 production.

Originally termed as “accessory cells” due to their surface expression of MHC class II (51), ILC2s have been suggested to have a function in modulating CD4+T cell–mediated immune response (56, 57). Indeed, recent studies demonstrate that ILC2s can facilitate the initiation of CD4+Th2 cell immune response at the sensitization phase of allergic lung inflammation (58, 59), possibly via a cell-cell contact– and MHC class II–dependent manners (37). Similarly, MHCII-expressing ILC2s are also shown to promote protective CD4+Th2 immune response against parasitic helminth infection (60). In support of these findings, our results also show that co-cultured ILC2s that expressed MHC class II could enhance type 2 cytokine production by OVA-specific CD4+Th2 cells in the presence of OVA peptide. Furthermore, we showed that co-transfer of ILC2s facilitated the Ag-driven CD4+Th2 cell immune response, which exacerbated airway inflammation, mucus production, and goblet cell hyperplasia in mice. Our results suggest that in addition to the role in facilitating the initiation of CD4+Th2 immune response, ILC2s may promote the re-activation of Ag-specific CD4+Th2 effector/memory cells, resulting in the exacerbation of chronic airway allergic inflammation. Thus, our findings point out a view that after allergic sensitization by DCs (61), infiltrated ILC2s may play an important accessory role to promote local allergen recall response at the chronic phase of allergic asthma, as recently suggested by Gasteiger et al. (62). The detailed molecular mechanisms by which ILC2s interact with Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells to promote allergen recall response remain to be determined.

Clinical studies suggest that a subgroup of patients with early-onset asthma exhibits eosinophilic inflammation that is associated with the increased number of lung T cells and decreased lung function and that this subgroup should be categorized as a major subphenotype of asthma driven by Th2 inflammation (1, 8, 9, 63). The observations from our studies using a murine model of chronic allergic lung diseases suggest that the increased lung-resident, Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells augment the capability of ILC2s to produce IL-13; reciprocally, ILC2s potentiate the response of Ag-specific Th2 cells to Ag re-exposure to produce elevated type 2 cytokines and exacerbate allergic airway inflammation. Our intriguing findings suggest that the persistent eosinophilic inflammation may be the consequence of the collaborative interactions between infiltrating ILC2s and the preferentially accumulated Ag-specific CD4+Th2 cells driven by recurrent allergen exposures. Whether such reciprocal interplays between innate ILC2s and adaptive CD4+Th2 cells underlie the mechanisms by which allergic individuals with early-onset asthma and the persistent eosinophilia phenotype later develop severe asthma remain to be examined. Further characterizations of the molecular mechanisms involved in the crosstalk between lung-resident CD4+Th2 cells and ILC2s may provide additional insights into the design of therapeutic approaches to prevent the exacerbation of severe allergic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Hottinger for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI090129) and American Lung Association / American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AI-169584-N).

ILC2s, type-2 innate lymphoid cells

CD4, cluster of differentiation 4

ROR-α, retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor alpha

GATA-3, GATA binding protein 3

AHR, airway hyperresponsiveness

WT, wild-type

BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Lin, Lineage

TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin protein

References

- 1.McDonald VM, Gibson PG. Exacerbations of severe asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;42:670–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:445–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley SJ, Goldthorpe S, Craven M, Morris J, Woodcock A, Custovic A. Exposure and sensitization to indoor allergens: association with lung function, bronchial reactivity, and exhaled nitric oxide measures in asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2003;112:362–368. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, Tsicopoulos A, Barkans J, Bentley AM, Corrigan C, Durham SR, Kay AB. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mojtabavi N, Dekan G, Stingl G, Epstein MM. Long-lived Th2 memory in experimental allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2002;169:4788–4796. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein MM. Targeting memory Th2 cells for the treatment of allergic asthma. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:107–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YH, Ito T, Homey B, Watanabe N, Martin R, Barnes CJ, McIntyre BW, Gilliet M, Kumar R, Yao Z, Liu YJ. Maintenance and polarization of human TH2 central memory T cells by thymic stromal lymphopoietin-activated dendritic cells. Immunity. 2006;24:827–838. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzel SE, Schwartz LB, Langmack EL, Halliday JL, Trudeau JB, Gibbs RL, Chu HW. Evidence that severe asthma can be divided pathologically into two inflammatory subtypes with distinct physiologic and clinical characteristics. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;160:1001–1008. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9812110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang YH, Wills-Karp M. The potential role of interleukin-17 in severe asthma. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2011;11:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosmi L, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. Th17 cells: new players in asthma pathogenesis. Allergy. 2011;66:989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcorn JF, Crowe CR, Kolls JK. TH17 cells in asthma and COPD. Annual review of physiology. 2010;72:495–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molet S, Hamid Q, Davoine F, Nutku E, Taha R, Page N, Olivenstein R, Elias J, Chakir J. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2001;108:430–438. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barczyk A, Pierzchala W, Sozanska E. Interleukin-17 in sputum correlates with airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. Respiratory medicine. 2003;97:726–733. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2003.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YH, Voo KS, Liu B, Chen CY, Uygungil B, Spoede W, Bernstein JA, Huston DP, Liu YJ. A novel subset of CD4(+) T(H)2 memory/effector cells that produce inflammatory IL-17 cytokine and promote the exacerbation of chronic allergic asthma. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:2479–2491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lajoie S, Lewkowich IP, Suzuki Y, Clark JR, Sproles AA, Dienger K, Budelsky AL, Wills-Karp M. Complement-mediated regulation of the IL-17A axis is a central genetic determinant of the severity of experimental allergic asthma. Nature immunology. 2010;11:928–935. doi: 10.1038/ni.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakashin H, Hirose K, Maezawa Y, Kagami S, Suto A, Watanabe N, Saito Y, Hatano M, Tokuhisa T, Iwakura Y, Puccetti P, Iwamoto I, Nakajima H. IL-23 and Th17 cells enhance Th2-cell-mediated eosinophilic airway inflammation in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:1023–1032. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-086OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallon PG, Ballantyne SJ, Mangan NE, Barlow JL, Dasvarma A, Hewett DR, McIlgorm A, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1105–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, Locksley RM. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Perrigoue JG, Spencer SP, Urban JF, Jr., Tocker JE, Budelsky AL, Kleinschek MA, Kastelein RA, Kambayashi T, Bhandoola A, Artis D. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature. 2010;464:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/nature08901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong SH, Walker JA, Jolin HE, Drynan LF, Hams E, Camelo A, Barlow JL, Neill DR, Panova V, Koch U, Radtke F, Hardman CS, Hwang YY, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nature immunology. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halim TY, MacLaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoyler T, Klose CS, Souabni A, Turqueti-Neves A, Pfeifer D, Rawlins EL, Voehringer D, Busslinger M, Diefenbach A. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37:634–648. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, McKenzie AN. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012;129:191–198. e191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamijo S, Takeda H, Tokura T, Suzuki M, Inui K, Hara M, Matsuda H, Matsuda A, Oboki K, Ohno T, Saito H, Nakae S, Sudo K, Suto H, Ichikawa S, Ogawa H, Okumura K, Takai T. IL-33-Mediated Innate Response and Adaptive Immune Cells Contribute to Maximum Responses of Protease Allergen-Induced Allergic Airway Inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;190:4489–4499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintz-Cole RA, Gibson AM, Bass SA, Budelsky AL, Reponen T, Hershey GK. Dectin-1 and IL-17A suppress murine asthma induced by Aspergillus versicolor but not Cladosporium cladosporioides due to differences in beta-glucan surface exposure. J Immunol. 2012;189:3609–3617. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swaidani S, Bulek K, Kang Z, Liu C, Lu Y, Yin W, Aronica M, Li X. The critical role of epithelial-derived Act1 in IL-17- and IL-25-mediated pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182:1631–1640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, Angelosanto JM, Laidlaw BJ, Yang CY, Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Turner D, Diamond JM, Goldrath AW, Farber DL, Collman RG, Wherry EJ, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1045–1054. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kheradmand F, Kiss A, Xu J, Lee SH, Kolattukudy PE, Corry DB. A protease-activated pathway underlying Th cell type 2 activation and allergic lung disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:5904–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan MH, Schindler U, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ. Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity. 1996;4:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Kephart GM, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33-responsive lineage-CD25+ CD44(hi) lymphoid cells mediate innate type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation in the lungs. J Immunol. 2012;188:1503–1513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE, Powrie F, Vivier E. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirchandani AS, Besnard AG, Yip E, Scott C, Bain CC, Cerovic V, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells drive CD4+ Th2 cell responses. J Immunol. 2014;192:2442–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chanez P, Wenzel SE, Anderson GP, Anto JM, Bel EH, Boulet LP, Brightling CE, Busse WW, Castro M, Dahlen B, Dahlen SE, Fabbri LM, Holgate ST, Humbert M, Gaga M, Joos GF, Levy B, Rabe KF, Sterk PJ, Wilson SJ, Vachier I. Severe asthma in adults: what are the important questions? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007;119:1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holgate ST, Polosa R. The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006;368:780–793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell MC, Busse WW. Severe asthma: an expanding and mounting clinical challenge. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2013;1:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Green RH. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;178:218–224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, Hargadon B, Parker D, Bradding P, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, Marshall RP, Bradding P, Green RH, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:973–984. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miranda C, Busacker A, Balzar S, Trudeau J, Wenzel SE. Distinguishing severe asthma phenotypes: role of age at onset and eosinophilic inflammation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2004;113:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saglani S, Lloyd CM. Eosinophils in the pathogenesis of paediatric severe asthma. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;14:143–148. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phipps S, Lam CE, Kaiko GE, Foo SY, Collison A, Mattes J, Barry J, Davidson S, Oreo K, Smith L, Mansell A, Matthaei KI, Foster PS. Toll/IL-1 signaling is critical for house dust mite-specific helper T cell type 2 and type 17 [corrected] responses. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;179:883–893. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-974OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnamoorthy N, Oriss TB, Paglia M, Fei M, Yarlagadda M, Vanhaesebroeck B, Ray A, Ray P. Activation of c-Kit in dendritic cells regulates T helper cell differentiation and allergic asthma. Nature medicine. 2008;14:565–573. doi: 10.1038/nm1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fattouh R, Pouladi MA, Alvarez D, Johnson JR, Walker TD, Goncharova S, Inman MD, Jordana M. House dust mite facilitates ovalbumin-specific allergic sensitization and airway inflammation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;172:314–321. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-198OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scanlon ST, Thomas SY, Ferreira CM, Bai L, Krausz T, Savage PB, Bendelac A. Airborne lipid antigens mobilize resident intravascular NKT cells to induce allergic airway inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2113–2124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu YJ, Soumelis V, Watanabe N, Ito T, Wang YH, Malefyt Rde W, Omori M, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. TSLP: an epithelial cell cytokine that regulates T cell differentiation by conditioning dendritic cell maturation. Annual review of immunology. 2007;25:193–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fort MM, Cheung J, Yen D, Li J, Zurawski SM, Lo S, Menon S, Clifford T, Hunte B, Lesley R, Muchamuel T, Hurst SD, Zurawski G, Leach MW, Gorman DM, Rennick DM. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hurst SD, Muchamuel T, Gorman DM, Gilbert JM, Clifford T, Kwan S, Menon S, Seymour B, Jackson C, Kung TT, Brieland JK, Zurawski SM, Chapman RW, Zurawski G, Coffman RL. New IL-17 family members promote Th1 or Th2 responses in the lung: in vivo function of the novel cytokine IL-25. J Immunol. 2002;169:443–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Krummel MF, Chawla A, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilhelm C, Hirota K, Stieglitz B, Van Snick J, Tolaini M, Lahl K, Sparwasser T, Helmby H, Stockinger B. An IL-9 fate reporter demonstrates the induction of an innate IL-9 response in lung inflammation. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ni.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Licona-Limon P, Kim LK, Palm NW, Flavell RA. TH2, allergy and group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nature immunology. 2013;14:536–542. doi: 10.1038/ni.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halim TY, McKenzie AN. New kids on the block: group 2 innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation in the lung. Chest. 2013;144:1681–1686. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gold MJ, Antignano F, Halim TY, Hirota JA, Blanchet MR, Zaph C, Takei F, McNagny KM. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells facilitate sensitization to local, but not systemic, TH2-inducing allergen exposures. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;133:1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halim TY, Steer CA, Matha L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, McKenzie AN, Takei F. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliphant CJ, Hwang YY, Walker JA, Salimi M, Wong SH, Brewer JM, Englezakis A, Barlow JL, Hams E, Scanlon ST, Ogg GS, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Dendritic cells and epithelial cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity in asthma. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nri2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gasteiger G, Rudensky AY. Interactions between innate and adaptive lymphocytes. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2014;14:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nri3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wenzel S. Severe asthma: from characteristics to phenotypes to endotypes. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;42:650–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.