Abstract

Lesions in DNA can block replication fork progression, leading to its collapse and gross chromosomal rearrangements. To circumvent such outcomes, the DNA damage tolerance (DDT) pathway becomes engaged, allowing the replisome to bypass a lesion and complete S phase. Chromatin remodeling complexes have been implicated in the DDT pathways, and here we identify the NuA4 remodeler, which is a histone acetyltransferase, to function on the translesion synthesis (TLS) branch of DDT. Genetic analyses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed synergistic sensitivity to MMS when NuA4 alleles, esa1-L254P and yng2Δ, were combined with the error-free bypass mutant ubc13Δ. The loss of viability was less pronounced when NuA4 complex mutants were disrupted in combination with error-prone/TLS factors, such as rev3Δ, suggesting an epistatic relationship between NuA4 and error-prone bypass. Consistent with cellular viability measurements, replication profiles after exposure to MMS indicated that small regions of unreplicated DNA or damage were present to a greater extent in esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ mutants, which persist beyond the completion of bulk replication compared to esa1-L254P/rev3Δ. The critical role of NuA4 in error-prone bypass is functional even after the bulk of replication is complete. Underscoring this observation, when Yng2 expression is restricted specifically to G2/M of the cell cycle, viability and TLS-dependent mutagenesis rates were restored. Lastly, disruption of HTZ1, which is a target of NuA4, also resulted in mutagenic rates of reversion on level with esa1-L254P and yng2Δ mutants, indicating that the histone variant H2A.Z functions in vivo on the TLS branch of DDT.

Keywords: NuA4, Esa1, Yng2, DNA damage tolerance, H2A.Z

CELLS have evolved mechanisms to repair various types of DNA lesions. However, if damage is present in S phase, then replication forks encountering these obstacles can collapse, resulting in breaks in the genome. To avoid such outcomes, all organisms rely on what are called the DNA damage tolerance (DDT) pathways, which allow bypass of the damage, either by an error-free or an error-prone mechanism. Central to DDT signaling is the ubiquitation (Ub) status of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Both branches require mono-Ub of PCNA on lysine 164 (K164) by Rad6 and Rad18, which are the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and ligase (E3), respectively (Hoege et al. 2002; Stelter and Ulrich 2003). Mono-Ub of K164 promotes error-prone bypass via low-fidelity translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases, which induce mutagenesis (Lehmann et al. 2007; Ulrich 2007). Mono-Ub PCNA can become poly-Ub via K63 linkage in a reaction mediated by Ubc13–Mms2 and Rad5, and this leads to error-free lesion bypass synthesis using the undamaged newly synthesized strand (template switch) (Branzei and Foiani 2007; Branzei 2011). Both of these pathways allow the completion of replication; however, the initial lesion remains for repair at a future time. The DDT pathway is functional in both S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and bulk replication proceeds to completion in the absence of the DDT pathway. Underscoring the importance of G2 events for preserving genomic stability, cellular viability is restored to wild-type levels when the expression of DDT factors, such as the TLS polymerase Rev3, are restricted to G2/M (Karras and Jentsch 2010; Karras et al. 2013).

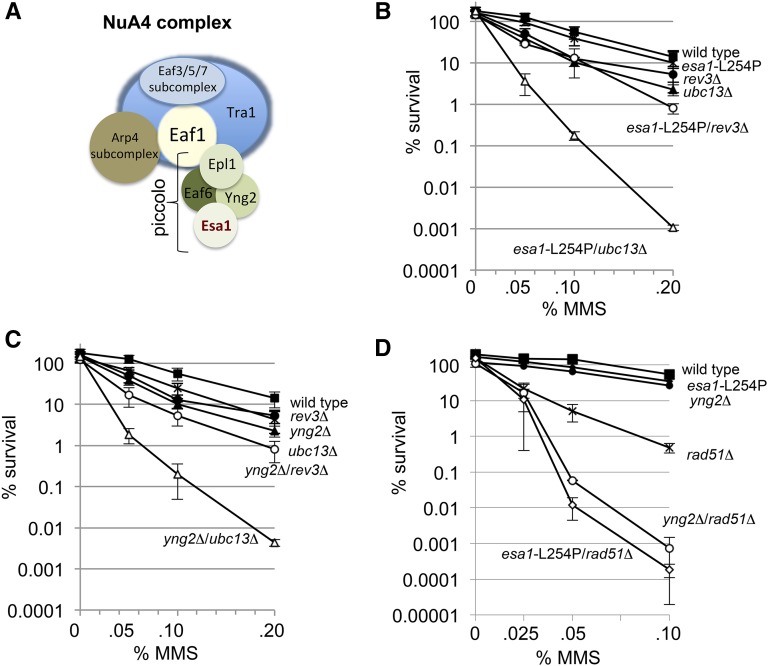

NuA4 is a multicomponent histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complex that primarily acetylates histone H4, H2A, and H2A.Z and functions in transcription and DNA repair (Lu et al. 2009; Price and D’Andrea 2013). Esa1 is the catalytic subunit and part of a NuA4 subcomplex called piccolo that also includes Yng2, Eaf6, and Epl1. Eaf1 is unique to the large complex and it interacts with Epl1 (Figure 1A). In the absence of EAF1, only piccolo NuA4 has activity (Auger et al. 2008; Mitchell et al. 2008). Although Esa1 is the catalytic component of NuA4, other proteins in the complex are required to mediate efficient acetylation. For example, the acetylation of histone H4 and variant H2A.Z are dramatically compromised in yng2Δ and eaf1Δ cells (Loewith et al. 2000; Choy et al. 2001; Choy and Kron 2002; Mehta et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

The NuA4 complex genetically interacts with the DNA damage tolerance (DDT) pathway. (A) Schematic of the NuA4 complex. Esa1 and Yng2 are part of the smaller piccolo NuA4 complex that also includes Epl1 and Eaf6. The large NuA4 complex forms when Epl1 in piccolo interacts with Eaf1. (B) Cell survival was measured after transient exposure to increasing concentrations of MMS for 1 hr at 30° for wild type (JC470), esa1-L254P (JC2767), ubc13Δ (JC2291), esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ (JC2775), rev3Δ (JC2289), and esa1-L254P/rev3Δ (JC2771), (C) yng2Δ (JC2036), yng2Δ/ubc13Δ (JC2285) and yng2Δ/rev3Δ (JC2281), or (D) rad51Δ (JC1362), esa1-L254P/rad51Δ (JC3253) and yng2Δ/rad51Δ (JC2437). Multiple experiments (three or more) were averaged with standard deviation being reported.

The histone variant H2A.Z, encoded by HTZ1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is incorporated into nucleosomes as an H2A.Z–H2B dimer by the ATP-dependent histone deposition complex, SWR1-C (Krogan et al. 2003; Kobor et al. 2004). NuA4 is important for the incorporation and acetylation of H2A.Z. NuA4 acetylates H4, which in turn recruits SWR1-C, the key complex that incorporates H2A.Z into chromatin (Babiarz et al. 2006; Keogh et al. 2006). The presence of H2A.Z functions as a barrier and prevents the spreading of heterochromatin (Meneghini et al. 2003; Babiarz et al. 2006) and its acetylation inhibits eviction by the chromatin remodeler INO80 (Papamichos-Chronakis et al. 2011). As with NuA4 and the INO80 complex (Morrison et al. 2004; Van Attikum et al. 2004; Downs and Cote 2005), H2A.Z also has a role in the DNA DSB response, where it is transiently deposited into chromatin on one side of the break, promoting DNA resection (Kalocsay et al. 2009). Additionally, H2A.Z is important during DNA replication. Combining the null mutation, htz1Δ, with S-phase checkpoint mutants, pol2-12, rad53-1, or mrc1-1, led to a synthetic growth defect. This phenotype is specific for the replication checkpoint, as the loss of canonical DNA damage checkpoint factors, such as CHK1 and RAD9, did not show the same defect with htz1Δ (Dhillon et al. 2006).

Chromatin modifiers, including NuA4, have been relatively well characterized in the context of DSB repair (reviewed in Papamichos-Chronakis and Peterson 2013; Price and D’Andrea 2013). Mutations in NuA4 result in methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) sensitivity (Clarke et al. 1999; Bird et al. 2002; Choy and Kron 2002; Auger et al. 2008), indicating the complex has a function in mediating the cellular response to replication stress, and cells lacking YNG2 show a defect in the DNA damage response during S phase (Choy and Kron 2002) and exhibit a delay in G2 (Choy et al. 2001). More recently, NuA4 and the RSC2 chromatin remodeler complexes were shown to be critical at trinucleotide repeats for homologous recombination (HR)-dependent postreplication gap repair (House et al. 2014). Taken together, there is an important relationship between the chromatin environment and the cellular response to damaged DNA during replication, and understanding how chromatin events can influence DDT as cells progress from S into G2, when template accessibility becomes restricted, remains to be explored and is the focus of our study.

Here we identify a role for the NuA4 complex in TLS that promotes cell survival as forks encounter damage. When the error-free tolerance pathway and NuA4 HAT activity are disrupted, as in esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ mutants, there is a discernible reduction in viability and chromosome integrity as cells try to deal with damage and recover from exposure to MMS during replication. Moreover, the rates of spontaneous mutagenesis measured with NuA4 mutants indicate a function for the complex in TLS/error-prone bypass, as endogenous damage is encountered during replication. In assessing known chromatin targets of NuA4, namely histone H4 and H2A.Z, we also see genetic interactions with DDT mutants, suggesting one main mechanism by which NuA4 permits TLS, is likely via modifications to chromatin.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and medium

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains used in the mutagenesis reversion assays are isogenic and derived from DBY747 (provided by Wei Xiao, University of Saskatchewan). All other strains are derived from W303 and are RAD5+. YPAD medium contain 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.003% adenine hemisulfate, and 2% glucose. Plates containing MMS (Aldrich 129925) were poured within a day of use.

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| JC470 | MATa ade2-1 trp1-1 his3-11 his3-15 ura3-1 leu2-3 leu2-112 Rad5+ (W303) | R. Rothstein |

| JC604 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK | This study |

| JC1362 | W303 MATa rad51Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2036 | W303 MATa yng2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| JC2090 | W303 MATa htz1Δ::URA3 | This study |

| JC2281 | W303 MATa yng2Δ::URA3 rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC2285 | W303 MATa yng2Δ::URA3 ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2289 | W303 MATa rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC2291 | W303 MATa ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2437 | W303 MATa rad51Δ::HIS3, yng2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| JC2520 | DBY747 MATa his3-D1 leu2-3, 112 trp1-289 ura3-52 | Xiao lab (D. Botstein) |

| JC2521 | DBY747 MATa ubc13Δ::HIS3 | Xiao lab (WXY8-49) |

| JC2524 | DBY747 MATa rev3Δ::LEU2 | Xiao lab (WXY93-82) |

| JC2535 | DBY747 MATa yng2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| JC2613 | DBY747 MATa yng2Δ::URA3 ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2696 | DBY747 MATa rev3Δ::LEU2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2762 | W303 MATa htz1Δ::URA3, rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC2764 | W303 MATa htz1Δ::URA3, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2767 | W303 MATa esa1-L254P::NatRMX4 | This study |

| JC2771 | W303 MATa esa1-L254P::NatRMX4, rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC2775 | W303 MATa esa1-L254P::NatRMX4, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2777 | W303 MATa rev3Δ::LEU2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC2978 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC2979 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3009 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, rev3Δ::LEU2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3053 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, esa1-L254P::NatRMX4, rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC3054 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, esa1-L254P::NatRMX4, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3060 | W303 MATa URA3::GPD-TK, esa1-L254P:: NatRMX4 | This study |

| JC3178 | W303 MATa hhf1::HIS3 hhf2::TRP1-hhf2-K5,8,12,16R HHT2 | This study |

| JC3179 | W303 MATa hhf1::HIS3 hhf2::TRP1-hhf2-K5,8,12,16R HHT2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3195 | W303 MATa hhf1::HIS3 hhf2::TRP1-hhf2-K5,8,12,16R HHT2, rev3Δ::LEU2 | This study |

| JC3207 | DBY747 MATa esa1-L254P:: NatRMX4 ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3216 | DBY747 MATa esa1-L254P:: NatRMX4 | This study |

| JC3253 | W303 MATa rad51Δ::HIS3, esa1-L254P:: NatRMX4 | This study |

| JC3255 | W303 MATa G2-yng2::natNT2 | This study |

| JC3257 | W303 MATa G2-yng2::natNT2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3376 | DBY747 MATa htz1Δ::URA3 | This study |

| JC3378 | DBY747 MATa htz1Δ::URA3, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| JC3387 | W303 MATa G2-yng2-10Flag-3xHIS3::KANMX6::natNT2 | This study |

| JC3588 | DBY747 MATa G2-yng2::natNT2 | This study |

| JC3590 | DBY747 MATa G2-yng2::natNT2, ubc13Δ::HIS3 | This study |

Survival assays

Exponentially growing cells were divided into the indicated concentrations of MMS for 1 hr before plating on YPAD. Plates were photographed using a FujiFilm LAS4000 Image Reader and colonies were counted using Cell Profiler (www.cellprofiler.org). Survivors for each strain were calculated as a percentage of viable cells before transient exposure to MMS. Each graph represents the average of experiments performed in triplicate. Drop assays were performed with 1:10 serial dilutions and plated on YPAD ± MMS.

Mutagenesis assay

All strains used in this assay were DBY747 background. This strain contains the trp1-289 amber allele and spontaneous reversion to TRP1+ is used as a measure of error-prone replication processes, resulting from the activity of TLS polymerases. Measurements were performed via the Luria and Delbruck fluctuation test as previously described (Broomfield et al. 1998). Strains were produced through integration of the URA3 cassette at the YNG2 and HTZ1 locus in the DBY747 strain background. To produce esa1-L254P in this background, PCR of the mutant ESA1 including the NAT resistance marker, was performed from a genomic preparation of JC2767 to generate linear DNA for transformation. To produce the G2–Yng2 construct, the PCR and transformation protocol used for the G2 assay was also used for the DBY747 background. Transformations were confirmed by PCR of genomic preps or sequencing and drop assays at the restrictive temperature for esa1-L254P (37°) to verify integration.

G2-tag

The G2-tag, composed of the promoter region and first 180 amino acids of Clb2 was integrated N terminal to YNG2, displacing 100 bp of the promoter region before the open reading frame. This region was built into the plasmid backbone of pYM–N31, and was a kind gift from the Jenstch lab (Karras and Jentsch 2010). To confirm the G2–Yng2 expression paralleled that of Clb2, Yng2 was also Flag-epitope tagged at its C terminus to enable detection via a different antibody than Clb2. G2–Yng2 was verified to be cell cycle regulated in the manner of endogenous Clb2 as previously described (Karras and Jentsch 2010). Briefly, cells were either arrested in G1 using α-factor before release into YPAD where samples were taken at 15-min intervals, or cells were arrested in nocodazole (7.5 µg/ml) for 2 hr followed by release into α-factor for 3 hr with samples taken at 1–3 hr in G1. TCA protein extractions were run on SDS–PAGE gels followed by Western blot analysis with antibodies to Clb2 (1:2000, sc-9071, Santa Cruz), Flag (1:1000, clone M2: F1804, Sigma), or Pgk1 (1:1000, 459250, Invitrogen) as a loading control. Additionally, cell cycle stage was monitored by flow cytometry.

PFGE

PFGE gel electrophoresis was performed as described and cells were cultured in the presence of 400 µg/ml bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma, B5002) to enable immunoblot analysis of newly synthesized DNA (Lengronne et al. 2001). Briefly, yeast cells were embedded in low-melting agarose plugs (2 × 107 cells/plug) and genomic DNA was extracted. Chromosomes were separated on a CHEF-DRII instrument (Bio-Rad) for 20 hr at 6 V/cm with switch time beginning at 60 sec and ending at 120 sec at 14°. Quantitation of chromosome intensity was performed by a modified Southern blotting procedure where the transfer is performed in a neutral pH buffer followed by immunoblot using an antibody that recognizes BrdU. Immunoblot of BrdU was performed in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, and 1% milk using a monoclonal antibody against BrdU (1:5000 clone 3D4: 555627, BD Biosciences) and a secondary ab conjugated to HRP. Images were acquired using a FujiFilm LAS4000 Image Reader. Quantitative densitometry was performed on chromosomes 7 and 15 where time points after the MMS chase were compared to levels immediately after MMS treatment (Bio-Rad Quantity One software).

Microarray and qPCR

Wild-type and esa1-L254P cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor for 2 hr and then treated with and without 0.05% MMS for 1 hr. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation and frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to transcriptome profiling and cell cycle progression was confirmed using flow cytometry. Sample preparation and hybridization onto 8 × 15 K Agilent yeast expression microarrays, as well as data normalization and analysis, were carried out based on the protocol described in Kwon et al. (2012). Cluster 3.0 (Eisen et al. 1998) and Java Treeview 1.1.6r2 (Saldanha 2004) were used to create heat-map images of microarray expression data (Supporting Information, Figure S6). The microarray expression data have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus Database and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE66176. Candidate genes from the microarray experiments were further validated by qPCR (Table S1). RNA was isolated as in the microarray experiments and complementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified and quantitated using the SYBR Green method.

Results

NuA4 complex components are epistatic with the TLS pathway

When both branches of the damage tolerance pathway are disrupted, cells are extremely sensitive to UV-induced and MMS-generated damage; lesions are recognized predominantly during DNA replication (Xiao et al. 1999; Brusky et al. 2000; Xiao et al. 2000). To investigate a potential role for the NuA4 complex in the damage tolerance pathway we took a genetic approach and combined a temperature-sensitive allele of the Esa1 acetyltransferase, esa1-L254P (Clarke et al. 1999), with mutants on either the error-free or error-prone/TLS branches of DDT. When esa1-L254P was combined with ubc13Δ or mms2Δ, mutants defective in error-free, there was profound sensitivity to growth on 0.002% MMS, a phenotype that was not observed when esa1-L254P was combined with rev3Δ or rev1Δ mutants defective on the error-prone/TLS branch (Figure S1A).

We continued characterizing the relationship of NuA4 with DDT by disrupting UBC13 or REV3 as representative factors of the error-free and error-prone/TLS branches, respectively. Transient 1-hr exposure to increasing amounts of MMS (0.05–0.2%) was performed to measure recovery after damage. There was ∼10-fold greater loss of viability with esa1-L254P/rev3Δ (1%) compared to the single mutants (10%), at 0.2% MMS concentrations (Figure 1B). However a profound synergistic loss of survival even after 0.05% MMS was observed with esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ double mutants (Figure 1B). Thus, while esa1-L254P shows a genetic interaction with both branches of the pathway, the greatest loss of recovery was observed when NuA4 activity was compromised in combination with the error-free branch.

We wanted to determine if other subcomponents of NuA4 exhibited similar interactions with the TLS branch and chose to disrupt YNG2 and EAF1. The deletion of YNG2 reduces the efficiency of NuA4 acetyltransferase activity, while an EAF1 deletion disrupts attachment of piccolo to the rest of the complex (Figure 1A) (Chittuluru et al. 2011). Cells harboring the yng2Δ mutation showed reduced growth on YPAD (Figure S1B); thus for quantitative survival measurements, we performed viability assays after MMS treatment. The sensitivity of yng2Δ and eaf1Δ cells to MMS was similar to esa1-L254P mutants (Figure S1C). Moreover, combining yng2Δ or eaf1Δ with the loss of UBC13 resulted in a reduction in survival upon MMS treatment that was indistinguishable from esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ mutants (Figure 1C and Figure S1, B–E).

The error-free pathway relies on homologous recombination (HR) components for template switching (Ball et al. 2009) and HR between newly replicated chromatids also rescues stalled replication forks in S phase (Lambert et al. 2005). Therefore, we reasoned that if NuA4 works in TLS then we should observe an additive, if not a synergistic loss of viability after MMS, when combining the loss of NuA4 and HR-specific functions. Indeed, the deletion of RAD51 in combination with either esa1-L254P or yng2Δ showed marked sensitivity to MMS (Figure 1D).

One definitive indicator of DDT branch involvement comes from measuring the mutagenic spontaneous rate of reversion. Polymerases involved in TLS can pair incorrect nucleotides across from a DNA lesion, thus mutations incorporated from TLS utilization can revert the nonfunctional trp1-289 allele to TRP+ (Broomfield et al. 1998). Consistent with previous reports (Brusky et al. 2000) the loss of UBC13 increases the spontaneous mutation rate because the error-prone TLS branch is the only available DDT pathway in ubc13Δ mutants (Table 2). This increase is dependent on a functional TLS pathway as rates for the rev3Δ ubc13Δ double mutants are almost as low as wild type (Table 2). Similar to the loss of REV3, both esa1-L254P and yng2Δ decreased the spontaneous rate of mutagenesis in ubc13Δ cells. The yng2Δ/ubc13Δ mutants have rates similar to rev3Δ/ubc13Δ, suggesting the function of NuA4 in TLS occurs in a “normal” S phase and not only in the presence of exogenous stress (Table 2).

Table 2. Spontaneous mutagenesis rate of reversion.

| Straina | Allele | Rate (× 10−8)b | Foldc |

|---|---|---|---|

| JC2520 | Wild type | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 1 |

| JC2521 | ubc13Δ | 92.07 ± 1.8 | 28 |

| JC2524 | rev3Δ | 1.24 ± 0.8 | 0.4 |

| JC2696 | rev3Δ/ubc13Δ | 13.5 ± 11.6 | 4 |

| JC3216 | esa1-L254P | 2.22 ± 1.1 | 0.7 |

| JC3207 | esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ | 44.1 ± 1.3 | 13 |

| JC2535 | yngΔ | 1.50 ± 1.1 | 0.5 |

| JC2613 | yngΔ/ubc13Δ | 10.9 ± 1.3 | 3 |

| JC3376 | htz1Δ | 8.5 ± 1.2 | 3 |

| JC3378 | htz1Δ/ubc13Δ | 42.64 ± 15.8 | 13 |

| JC3588 | G2-Yng2 | 2.72 ± 1.3 | 0.7 |

| JC3590 | G2-Yng2/ubc13Δ | 82.4 ± 0.7 | 21 |

All strains are isogenic derivatives of DBY747.

The spontaneous mutation rates are the average of at least three independent experiments with standard deviations.

Expressed fold difference compared to wild type.

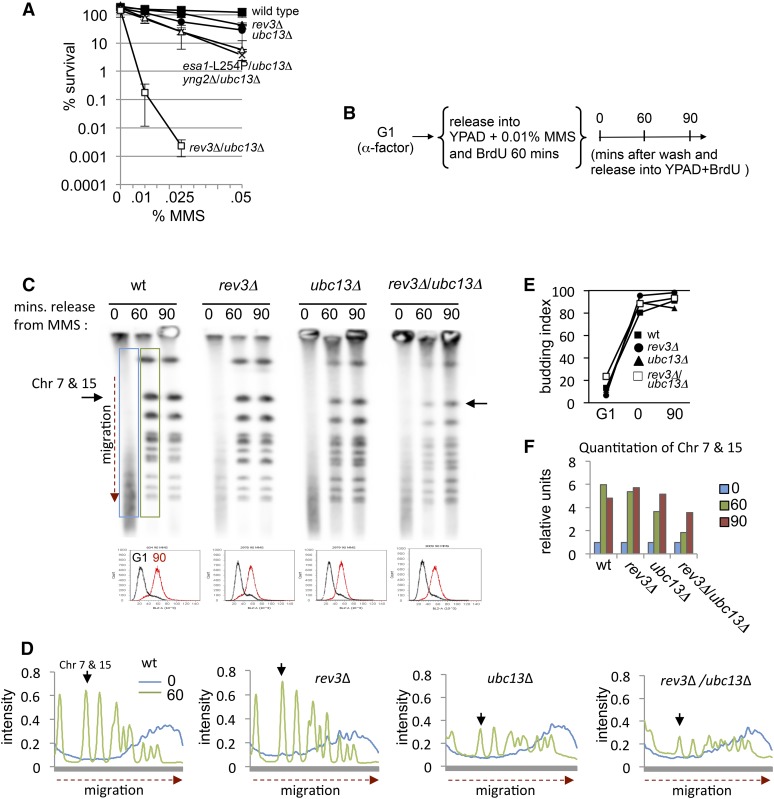

Chromosome integrity is compromised in the absence of the DDT pathway

As mentioned above, when both branches of the DDT pathway are compromised, as with rev3Δ/ubc13Δ mutants, there is a dramatic loss of cell survival after transient exposure to MMS (Figure 2A) (Xiao et al. 1999; Brusky et al. 2000; Xiao et al. 2000). To visualize chromosome integrity in these mutants specifically during replication, we performed PFGE in the presence of BrdU, allowing us to monitor intact chromosomes specifically during DNA replication as cells traverse S phase. Cells were synchronized in G1 with α-factor, then released into 0.01% MMS for 1 hr before recovery in YPAD (Figure 2B). For wild-type cells, intact chromosomes entered the gel and S phase was complete by 60 min (Figure 2, C–F). The migration patterns of cells lacking REV3 look very similar to wild type (Figure 2, C and D) and consistent with rev3Δ mutants having a similar rate of chromosomal rearrangements compared to wild type (Schmidt et al. 2010). However, there was a measurable defect in the recovery of ubc13Δ cells (Figure 2, C–F), which is consistent with error-free being the dominant pathway for lesion bypass during S phase (Huang et al. 2013). Migration was compromised further in rev3Δ/ubc13Δ mutants, and even at 90 min, a reduction of intact newly synthesized chromosomes was measured (Figure 2F). This profile is indicative of persistent DNA damage or small gaps that prevent chromosome entry and correlates with the MMS sensitivity observed when both the error-prone and the error-free pathways are disrupted (Figure 2, A, C, and D). There were no delays in the G1/S transition or the completion of bulk replication during S phase as measured by budding index and flow cytometry (Figure 2, C and E). This is consistent with the observations of rad18Δ mutants, which fail to delay S phase progression upon MMS treatment, when both error-prone and error-free pathways are nonfunctional (Huang et al. 2013). However, cells lacking RAD18 do exhibit a G2/M arrest from “secondary” damage, such as single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gaps, arising from defects in repair behind the fork and not directly from the initial alkylation lesions (Huang et al. 2013).

Figure 2.

Decreased cell survival after MMS exposure correlates with DNA damage in G2. (A) Cell survival was measured after transient exposure to increasing concentrations of MMS for 1 hr with wild type (JC470), ubc13Δ (JC2291), rev3Δ (JC2289), and rev3Δ/ubc13Δ (JC2777). (B) Cells were arrested in α-factor for 2 hr followed by release into YPAD media containing bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 400 µg/ml) and 0.01% MMS for 1 hr. Following MMS treatment, cells were released into YPAD + BrdU before samples were collected at the indicated time points. (C) Pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed, followed by a Southern transfer to nitrocellulose, and blotted with α-BrdU antibodies in wild type (JC604), rev3Δ (JC2978), ubc13Δ (JC2979), and rev3Δ/ubc13Δ (JC3009). The cell cycle stage was monitored by flow cytometry where G1 (black) and the 90-min time points after MMS release (red) are shown. (D) The BrdU signal at the 0 min (blue) and 60 min (green) time points were quantified by ImageJ with the migration distance of chromosomes vs. the intensity of BrdU plotted, giving a measure of newly synthesized chromosomes during one round of DNA replication. (E) Budding index was performed with samples to measure G1/S transition. (F) Quantitative densitometry was performed on the BrdU signal from chromosomes 7 and 15 after release from MMS using Bio-Rad Quantity One software at 0 min (blue), 60 min (green), and 90 min (red).

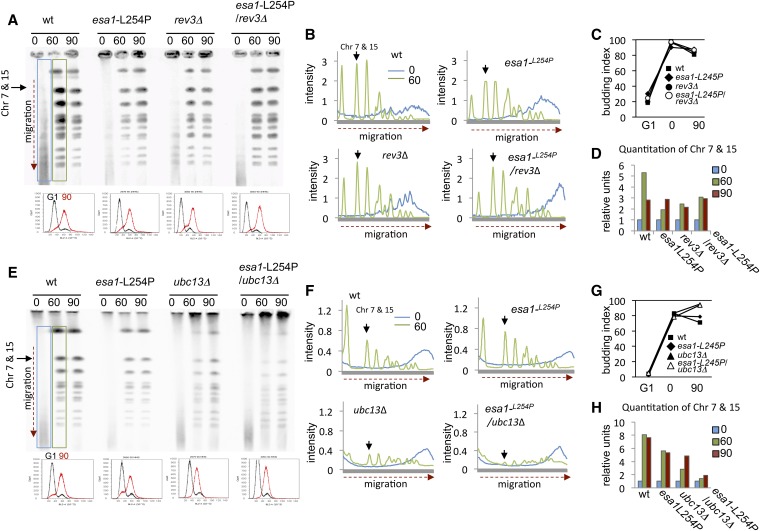

In previous PFGE experiments performed in asynchronous conditions, yng2Δ mutants showed persistent DNA damage after MMS treatment (Choy and Kron 2002). Cells lacking YNG2 showed a slight growth delay (Figure S1B) and we never achieved effective synchronization of yng2Δ mutants. Therefore to characterize NuA4 in replication we combined the esa1-L254P allele with DDT pathway mutants (Figure 3). Compared to wild-type cells, esa1-L254P mutants showed a slight defect in chromosome migration, which did not change by the further loss of REV3 (Figure 3, A–D; Figure S3). However, esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ double mutant cells showed a dramatic reduction in chromosome entry even when the bulk of replication, as monitored by flow cytometry, was complete (Figure 3, E–H; Figure S4). Thus, similar to rev3Δ/ubc13Δ mutants, the loss of NuA4 specifically with disruption of the error-free branch resulted in replication-associated DNA damage. Moreover, in rev3Δ/ubc13Δ and esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ double mutants, the loss of chromosome integrity as cells traverse S phase is dependent on MMS. The entry of newly synthesized DNA purified from these mutants entered the gel and migrated at levels indistinguishable from wild type after 150 min release into YPAD + nocodazole to prevent mitosis (Figure S2B; Figure S4A).

Figure 3.

DNA lesions remain in G2 when the error-free pathway is disrupted in combination with the loss of NuA4 acetyltransferase activity. PFGE, cell cycle progression, and quantification were determined (as in Figure 2) for (A–D) wild type (JC604), esa1-L254P (JC3060), rev3Δ (JC2978), and esa1-L254P/rev3Δ (JC3053) and (E–H) ubc13Δ (JC2979) and esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ (JC3054).

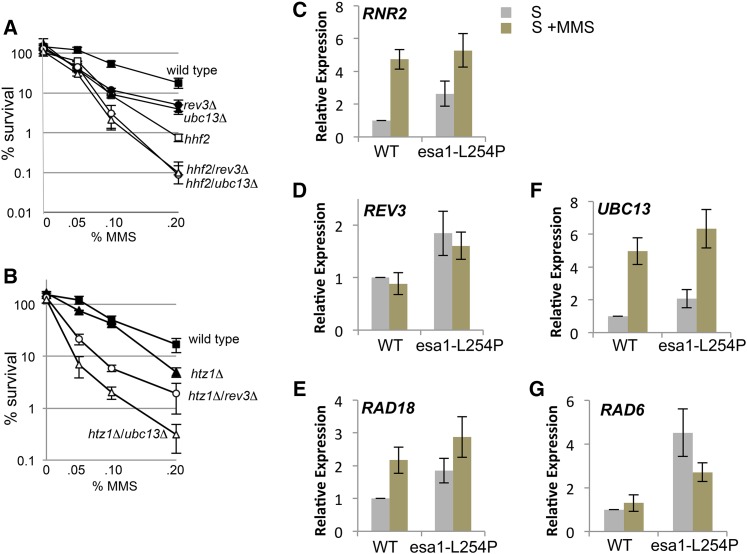

NuA4 targets of acetylation interact genetically with the DDT pathway

To determine if known chromatin substrates of NuA4 contribute to TLS, we investigated histone H4 and H2A.Z. Acetylation of H4 is important for the cellular response to DNA damage (Megee et al. 1995; Bird et al. 2002), and we performed viability experiments when DDT pathway mutants were combined with a histone H4 allele where its acetylation sites, K5, K8, K12, and K16 were mutated to arginine, hhf2K→R. Both double mutants were more sensitive than either respective single mutant, with hhf2K→R/ubc13Δ mutant cells being the most sensitive (Figure S5A). However, we did not observe a differential sensitivity between the double mutants after transient exposure to MMS (Figure 4A). When the hhf2K→R mutant was combined with either rev3Δ or ubc13Δ both double mutants showed a similar loss of viability between the levels measured for esa1-L254P/rev3Δ and esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ at 0.2% MMS (compare Figure 4A with Figure 1B). Why the hhf2K→R/rev3Δ mutant is more sensitive than the esa1-L254P/rev3Δ remains to be determined. It could be that there is compensation from another acetyltransferase such as Hat1, which targets histone H4 for K12 acetylation (Ai and Parthun 2004; Li et al. 2014).

Figure 4.

Transcription of DDT factors is not dramatically altered in esa1-L254P mutants upon MMS treatment. (A) Viability assays as described in Figure 1 were performed for wild type (JC470), rev3Δ (JC2289), ubc13Δ (JC2291), hhf2K→R (JC3178), hhf2K→R/rev3Δ (JC3195), hhf2K→R/ubc13Δ (JC3179) and (B) htz1Δ (JC2090), htz1Δ/rev3Δ (JC2762), and htz1Δ/ubc13Δ (JC2764). (C–G) qRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods was performed on wild-type and esa1-L254P cells treated with α-factor for 2 hr followed by release into normal YPAD (S phase) or YPAD with 0.05% MMS (S + MMS) for 1 hr. Candidate genes in the DDT pathway were analyzed for expression with and without MMS. The qRT-PCR values from target genes were normalized to ALG9 (Table S1), as its transcript levels were most stable throughout the cell cycle.

In contrast to histone H4 mutants, which showed similar genetic interaction with both branches of DDT, the disruption of HTZ1, in combination with ubc13Δ was more sensitive to MMS than either single mutant and more sensitive than htz1Δ/rev3Δ (Figure 4B; Figure S5B). While htz1Δ/ubc13Δ cells show an additive genetic interaction, they were not as sensitive to MMS as either esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ or yng2Δ/ubc13Δ double mutants (compare Figures 1, B and C with Figure 4B), which demonstrates the role of NuA4 in damage tolerance extends beyond H2A.Z-mediated events. Nonetheless, the loss of HTZ1 reduced the endogenous spontaneous rate of mutagenesis in ubc13Δ to the same degree as esa1-L254P (∼13-fold over wild type), which is half that of cells lacking UBC13 alone (28-fold over wild type; Table 2), indicating that H2A.Z has a very important role in TLS.

Transcriptional analysis of esa1-L254P mutants during MMS treatment

Histone acetylation, both H4 and H2A.Z, is critical for transcriptional regulation, thus we investigated if NuA4 impinged on the tolerance pathway via transcriptional alterations in DDT factors or target genes in the DNA damage response. To this end, we first took an unbiased approach and performed microarray analysis to assess the genome-wide levels of transcription in wild-type vs. esa1-L254P cells during MMS treatment. Samples were prepared from cells synchronized with α-factor and released into YPAD ± 0.05% MMS for 1 hr. A similar pattern of expression was observed globally in esa1-L254P mutants compared to wild-type cells in response to MMS, including genes that participate in the DNA damage response pathways and DDT (Figure S6).

We next performed qRT-PCR to validate the expression of candidate genes in the DDT pathway and a representative component of the DNA damage response. Similar to wild-type cells, RNR2 expression was up-regulated in esa1-L254P mutants in response to MMS. This is consistent with what has been observed with other NuA4 factors, as yng2Δ mutants were able to up-regulate RNR3 (Figure 4C) (Choy and Kron 2002). Furthermore, when challenged with MMS, esa1-L254P mutants showed similar levels of expression compared to wild type for the DDT factors we measured (Figure 4, D–G). Even though global expression patterns are similar, some differences were observed (Figure S6B), so we cannot dismiss esa1-L254P-dependent transcriptional changes that might impinge on the damage tolerance pathway. However, the expression patterns of factors directly involved in the error-prone and error-free branches are not dramatically altered, suggesting defects in their transcriptional levels are not responsible for the loss of recovery when NuA4 mutants are combined with the loss of UBC13.

Restricting Yng2 to G2/M fully supports TLS

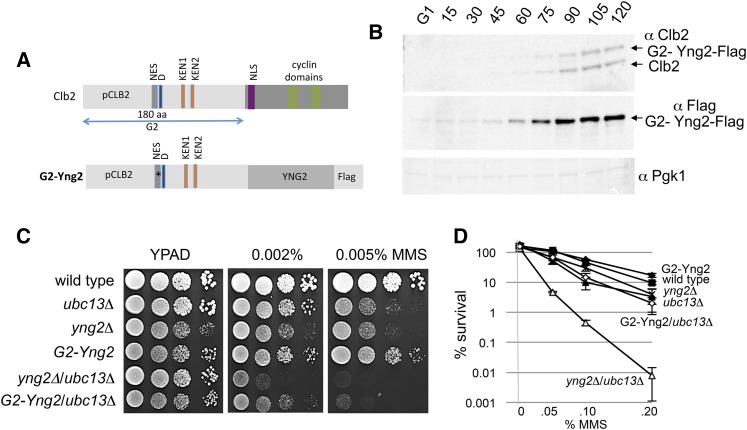

Restricting the expression of DDT factors, both TLS and error-free, to G2/M fully supported damage tolerance and indicated that TLS can occur after S phase (Karras and Jentsch 2010). This was demonstrated by expressing REV3 from late S to G2 by fusing it to the regulatory elements of Clb2, which is a mitotic cyclin expressed only in G2/M before its rapid degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome system that targets D- and KEN-box degrons (Figure 5A) (Karras and Jentsch 2010). We took a similar approach and restricted the expression of YNG2. A G2–Yng2 fusion protein was generated where the CLB2 promoter sequence and the N-terminal 180 aa were inserted in front of the YNG2 open reading frame (Figure 5A). The expression pattern of the G2–YNG2 fusion was indistinguishable from Clb2 (Figure 5B; Figure S7). Similar to yng2Δ cells, G2–Yng2 mutants were slightly slow growing compared to wild type (Figure 5C); however, in contrast to yng2Δ mutants, the sensitivity of G2–YNG2 to MMS was similar to wild-type cells (Figure 5, C and D). Moreover, the sensitivity of G2–YNG2/ubc13Δ mutant cells to MMS approached the levels measured with ubc13Δ single mutants (Figure 5D). The deletion of YNG2 completely abrogated the TLS pathway and the spontaneous rate of mutagenesis observed in yng2Δ/ubc13Δ was indistinguishable from that of rev3Δ/ubc13Δ cells (Table 2). However, TLS was fully restored in cells where Yng2 was expressed only in G2/M, as the spontaneous rate of mutagenesis in G2–YNG2/ubc13Δ double mutants is approximately equal to the rates measured in ubc13Δ cells (Table 2). In all, our data support a function for NuA4 in TLS after S phase that is fully functional in G2.

Figure 5.

Restricting expression of the NuA4 subunit Yng2 to G2 of the cell cycle rescues the cellular viability after MMS treatment. (A) Schematic of Clb2 (top panel) showing the nuclear-export signal (gray), D (blue), KEN boxes (orange), the nuclear localization signal (purple), and two cyclin domains (green). In G2–Yng2 (bottom panel) the YNG2 gene was fused to the G2 tag (Karras and Jentsch 2010), which includes the DNA sequence of the CLB2 promoter (pCLB2; activated in G2) and 180 aa of Clb2 with the nuclear export signal mutated, L26A, indicated by an asterisk (*) and the D- and KEN-box degrons. The G2 tag reacts with the Clb2 antibody and for the purposes of determining expression patterns by Western blot the G2–Yng2 fusion was further Flag tagged because it was difficult to differentiate G2–Yng2 from Clb2 due to their sizes. All subsequent analyses were performed with a G2–Yng2 fusion that did not have a Flag epitope tag. (B) G2–Yng2 and Clb2 are expressed only in G2/M. G2–Yng2–10Flag cells (JC3387) were arrested in G1 with α-factor for 3 hr, followed by release into YPAD with samples collected at the indicated time points prior to SDS–PAGE and Western blot analysis with α-Clb2, α-Flag (to visualize G2–Yng2–Flag), and α-Pgk1 as a loading control. (C and D) Drop assays (1:10 serial dilutions) from exponentially growing cultures were performed on YPAD ± media containing the indicated concentrations of MMS at 30° and viability assays as described in Figure 1 were performed for wild type (JC470), ubc13Δ (JC2291), yng2Δ (JC2036), G2–YNG2 (JC3255), yng2Δ/ubc13Δ (JC2285), and G2–YNG2/ubc13Δ (JC3257).

Discussion

The DDT pathway allows for the bypass of DNA damage that is present during replication. Chromatin reassembly after fork passage and how the chromatin environment contributes to DDT function is only starting to be considered (Falbo et al. 2009; Ball et al. 2014; Gonzalez-Huici et al. 2014; House et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2014). Our data indicate that the histone acetyltransferase, NuA4, has a role in DDT with a measureable role in error-prone/TLS bypass. While DDT reduces the frequency of fork collapse, there is a paradox because engagement of the error-prone/TLS branch leads to increased mutagenesis in addition to retention of the original lesion. When the error-free pathway is disrupted, the rate of mutagenesis increases as all forks encountering obstacles are processed via the error-prone branch of the pathway. When both pathways are disrupted, as with the ubc13Δ/rev3Δ double mutant, the rate of mutagenesis reverts; however, this also coincides with a severe loss of viability after exposure to DNA damage. Two NuA4 alleles, esa1-L254P and yng2Δ, as well as htz1Δ mutant cells exhibit phenotypes consistent with their involvement in the error-prone branch. When combined with the loss of UBC13, the double mutants showed additive sensitivity to MMS and all decreased the mutagenic reversion rates in ubc13Δ background cells.

Our data suggest that the function of NuA4 is not attributable to specific changes in transcription, which could indirectly alter the kinetics of repair. We did not observe dramatic changes in the expression patterns of DDT pathway members or DNA damage response genes when comparing esa1-L254P to wild-type cells. However, when chromosome integrity was monitored during replication by PFGE, damage persisted in rev3Δ/ubc13Δ and esa1-L254P/ubc13Δ mutants alike. Unfortunately, performing PFGE on synchronized cultures as in Figure 2 and Figure 3 was challenging to interpret for yng2Δ and htz1Δ cells, as these mutants exhibit cell cycle defects and S phase alteration even in the absence of MMS exposure (Dhillon and Kamakaka 2000; Choy and Kron 2002). Taken together, our data are consistent with a model that NuA4 has a direct role in error-prone/TLS damage tolerance rather than controlling the transcription of TLS factors. Unfortunately, DNA alkylation generated by MMS exposure is indiscriminate in nature, precluding site-specific recruitment studies, such as chromatin immunoprecipitation, with NuA4 complex components.

Chromatin targets of NuA4 that influence genome stability are histone variant H2A.Z, encoded by HTZ1, and histone H4 (Papamichos-Chronakis and Peterson 2013). The role of H4 acetylation in the DNA damage response is to loosen nucleosome interactions and to serve as a substrate for chromatin remodelers such as SWR1-C and RSC2. Similar to H2A.Z, histone H4 acetylation is important for error-prone/TLS; however, in contrast to H2A.Z, but consistent with House et al. (2014), we found that H4 acetylation is also important in error-free bypass after exposure to MMS. Interestingly, cells harboring hhf2K→R led to a greater loss of viability when combined with rev3Δ (Figure 4A) compared to the NuA4/rev3Δ double mutants, perhaps indicating NuA4-independent modifications to histone H4 in error-free bypass.

We find the htz1Δ mutation resembles cells that have lost NuA4 activity (Figure 4B; Table 2). Indeed, deletion of HTZ1 renders cells more sensitive to MMS when combined with either ubc13Δ or rev3Δ, but shows the strongest genetic interaction when combined with ubc13Δ. Importantly, htz1Δ reduced the mutagenic rate of ubc13Δ to the level of esa1-L259/ubc13Δ double mutants (Table 2), indicating the involvement of both NuA4 and H2A.Z in TLS bypass. Indeed, NuA4 activity drives H2A.Z incorporation (Durant and Pugh 2007; Altaf et al. 2009; Altaf et al. 2010), and nucleosomes containing H2A.Z promote a more flexible chromatin environment (Babiarz et al. 2006), which would keep newly assembled chromatin behind the fork in an accessible state. Characterization of H2A.Z in transcription has shown its enrichment at promoter regions from a characteristic chromatin pattern, defined by its incorporation in two nucleosomes flanking a nucleosome-depleted region (Yuan et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2007; Cairns 2009).

We speculate that perhaps ssDNA gaps are similar to this structural pattern and that H2A.Z helps maintain these genomic regions in a state conducive to the recruitment of error-prone/TLS factors. Expanding on potential function(s), ssDNA gaps are innately fragile and susceptible to double-stranded break (DSB) formation. The presence of H2A.Z at these regions would augment DSB repair (Adkins et al. 2013) or, if irreparable, aid in DNA break relocalization to the nuclear periphery (Horigome et al. 2014). We predicted there would be less chromatin associated H2A.Z in esa1-L254P cells upon MMS treatment; however, fractionation experiments showed no discernible change in H2A.Z levels in mutants compared to wild-type cells (Figure S8). Differences could be below detection, as previous work monitoring the level of chromatin bound H2A.Z in cells lacking INO80, which catalyzes its eviction, suggest subtle H2A.Z redistribution at specific loci is not reflected by changes in H2A.Z levels in bulk chromatin (Papamichos-Chronakis et al. 2011).

A number of groups have shown that bulk replication is able to finish in the absence of the DDT pathway (Liberi et al. 2005; Lopes et al. 2006; Branzei et al. 2008; Karras and Jentsch 2010) and that ssDNA gaps, which contain the lesion, are generated after the replicative polymerases move past the site of damage (Lehmann and Fuchs 2006; Karras and Jentsch 2010). A model has been presented that error-free bypass commences in S phase and is the preferred branch; however, if the lesion cannot be bypassed, then the Mec1 checkpoint is activated and error-prone/TLS bypass proceeds subsequent to S phase (Karras and Jentsch 2010). When the expression of TLS polymerases is restricted to G2/M, error-prone bypass operates effectively (Karras and Jentsch 2010). Utilizing the same “G2-tag” system with Yng2 fully rescued the viability of cells exposed to MMS and restored the high rate of mutagenesis when combined with the loss of UBC13. This study does not exclude additional roles for NuA4 or even an S phase role for the complex in TLS during normal cell cycle progression. However, our data do identify the critical function of NuA4 in TLS is fully restored when its expression is restricted to G2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Jentsch for the G2-tagging plasmid pGIK43 (D3218) and Wei Xiao and Lindsay Ball for advice and yeast strains. For their experimental expertise, we appreciate Armelle Lengronne and Georgios Karras. This work was supported by Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions (salary to J.C.) and by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP-82736, MOP-137062, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council 418122 awarded to J.C. G.C. is supported by research grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Canada Foundation for Innovation. M.R.-Y., K.C.-R., and I.G. are supported by Queen Elizabeth II graduate scholarships.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.174490/-/DC1.

Communicating editor: J. A. Nickoloff

Literature Cited

- Adkins N. L., Niu H., Sung P., Peterson C. L., 2013. Nucleosome dynamics regulates DNA processing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20: 836–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai X., Parthun M. R., 2004. The nuclear Hat1p/Hat2p complex: a molecular link between type B histone acetyltransferases and chromatin assembly. Mol. Cell 14: 195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaf M., Auger A., Covic M., Cote J., 2009. Connection between histone H2A variants and chromatin remodeling complexes. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87: 35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaf M., Auger A., Monnet-Saksouk J., Brodeur J., Piquet S., et al. , 2010. NuA4-dependent acetylation of nucleosomal histones H4 and H2A directly stimulates incorporation of H2A.Z by the SWR1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 15966–15977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger A., Galarneau L., Altaf M., Nourani A., Doyon Y., et al. , 2008. Eaf1 is the platform for NuA4 molecular assembly that evolutionarily links chromatin acetylation to ATP-dependent exchange of histone H2A variants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 2257–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiarz J. E., Halley J. E., Rine J., 2006. Telomeric heterochromatin boundaries require NuA4-dependent acetylation of histone variant H2A.Z in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 20: 700–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. G., Zhang K., Cobb J. A., Boone C., Xiao W., 2009. The yeast Shu complex couples error-free post-replication repair to homologous recombination. Mol. Microbiol. 73: 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball L. G., Xu X., Blackwell S., Hanna M. D., Lambrecht A. D., et al. , 2014. The Rad5 helicase activity is dispensable for error-free DNA post-replication repair. DNA Repair (Amst.) 16: 74–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. W., Yu D. Y., Pray-Grant M. G., Qiu Q., Harmon K. E., et al. , 2002. Acetylation of histone H4 by Esa1 is required for DNA double-strand break repair. Nature 419: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., 2011. Ubiquitin family modifications and template switching. FEBS Lett. 585: 2810–2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., Foiani M., 2007. Template switching: from replication fork repair to genome rearrangements. Cell 131: 1228–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., Vanoli F., Foiani M., 2008. SUMOylation regulates Rad18-mediated template switch. Nature 456: 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomfield S., Chow B. L., Xiao W., 1998. MMS2, encoding a ubiquitin-conjugating-enzyme-like protein, is a member of the yeast error-free postreplication repair pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 5678–5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusky J., Zhu Y., Xiao W., 2000. UBC13, a DNA-damage-inducible gene, is a member of the error-free postreplication repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 37: 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns B. R., 2009. The logic of chromatin architecture and remodelling at promoters. Nature 461: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittuluru J. R., Chaban Y., Monnet-Saksouk J., Carrozza M. J., Sapountzi V., et al. , 2011. Structure and nucleosome interaction of the yeast NuA4 and Piccolo-NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complexes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18: 1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy J. S., Kron S. J., 2002. NuA4 subunit Yng2 function in intra-S-phase DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 8215–8225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy J. S., Tobe B. T., Huh J. H., Kron S. J., 2001. Yng2p-dependent NuA4 histone H4 acetylation activity is required for mitotic and meiotic progression. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 43653–43662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A. S., Lowell J. E., Jacobson S. J., Pillus L., 1999. Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon N., Kamakaka R. T., 2000. A histone variant, Htz1p, and a Sir1p-like protein, Esc2p, mediate silencing at HMR. Mol. Cell 6: 769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon N., Oki M., Szyjka S. J., Aparicio O. M., Kamakaka R. T., 2006. H2A.Z functions to regulate progression through the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs J. A., Cote J., 2005. Dynamics of chromatin during the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle 4: 1373–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant M., Pugh B. F., 2007. NuA4-directed chromatin transactions throughout the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 5327–5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M. B., Spellman P. T., Brown P. O., Botstein D., 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falbo K. B., Alabert C., Katou Y., Wu S., Han J., et al. , 2009. Involvement of a chromatin remodeling complex in damage tolerance during DNA replication. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16: 1167–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Huici V., Szakal B., Urulangodi M., Psakhye I., Castellucci F., et al. , 2014. DNA bending facilitates the error-free DNA damage tolerance pathway and upholds genome integrity. EMBO J. 33: 327–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoege C., Pfander B., Moldovan G. L., Pyrowolakis G., Jentsch S., 2002. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigome C., Oma Y., Konishi T., Schmid R., Marcomini I., et al. , 2014. SWR1 and INO80 chromatin remodelers contribute to DNA double-strand break perinuclear anchorage site choice. Mol. Cell 55: 626–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House N. C., Yang J. H., Walsh S. C., Moy J. M., Freudenreich C. H., 2014. NuA4 initiates dynamic histone H4 acetylation to promote high-fidelity sister chromatid recombination at postreplication gaps. Mol. Cell 55: 818–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Piening B. D., Paulovich A. G., 2013. The preference for error-free or error-prone postreplication repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae exposed to low-dose methyl methanesulfonate is cell cycle dependent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33: 1515–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalocsay M., Hiller N. J., Jentsch S., 2009. Chromosome-wide Rad51 spreading and SUMO-H2A.Z-dependent chromosome fixation in response to a persistent DNA double-strand break. Mol. Cell 33: 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras G. I., Jentsch S., 2010. The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell 141: 255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras G. I., Fumasoni M., Sienski G., Vanoli F., Branzei D., et al. , 2013. Noncanonical role of the 9-1-1 clamp in the error-free DNA damage tolerance pathway. Mol. Cell 49: 536–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh M. C., Mennella T. A., Sawa C., Berthelet S., Krogan N. J., et al. , 2006. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A variant Htz1 is acetylated by NuA4. Genes Dev. 20: 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Dejsuphong D., Adelmant G., Ceccaldi R., Yang K., et al. , 2014. Transcriptional repressor ZBTB1 promotes chromatin remodeling and translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 54: 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobor M. S., Venkatasubrahmanyam S., Meneghini M. D., Gin J. W., Jennings J. L., et al. , 2004. A protein complex containing the conserved Swi2/Snf2-related ATPase Swr1p deposits histone variant H2A.Z into euchromatin. PLoS Biol. 2: E131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan N. J., Keogh M. C., Datta N., Sawa C., Ryan O. W., et al. , 2003. A Snf2 family ATPase complex required for recruitment of the histone H2A variant Htz1. Mol. Cell 12: 1565–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon E. J., Laderoute A., Chatfield-Reed K., Vachon L., Karagiannis J., et al. , 2012. Deciphering the transcriptional-regulatory network of flocculation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS Genet. 8: e1003104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S., Watson A., Sheedy D. M., Martin B., Carr A. M., 2005. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell 121: 689–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W., Tillo D., Bray N., Morse R. H., Davis R. W., et al. , 2007. A high-resolution atlas of nucleosome occupancy in yeast. Nat. Genet. 39: 1235–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A. R., Fuchs R. P., 2006. Gaps and forks in DNA replication: rediscovering old models. DNA Repair (Amst.) 5: 1495–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A. R., Niimi A., Ogi T., Brown S., Sabbioneda S., et al. , 2007. Translesion synthesis: Y-family polymerases and the polymerase switch. DNA Repair (Amst.) 6: 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A., Pasero P., Bensimon A., Schwob E., 2001. Monitoring S phase progression globally and locally using BrdU incorporation in TK(+) yeast strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 1433–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang L., Liu T., Chai C., Fang Q., et al. , 2014. Hat2p recognizes the histone H3 tail to specify the acetylation of the newly synthesized H3/H4 heterodimer by the Hat1p/Hat2p complex. Genes Dev. 28: 1217–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberi G., Maffioletti G., Lucca C., Chiolo I., Baryshnikova A., et al. , 2005. Rad51-dependent DNA structures accumulate at damaged replication forks in sgs1 mutants defective in the yeast ortholog of BLM RecQ helicase. Genes Dev. 19: 339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R., Meijer M., Lees-Miller S. P., Riabowol K., Young D., 2000. Three yeast proteins related to the human candidate tumor suppressor p33(ING1) are associated with histone acetyltransferase activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 3807–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M., Foiani M., Sogo J. M., 2006. Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol. Cell 21: 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P. Y., Levesque N., Kobor M. S., 2009. NuA4 and SWR1-C: two chromatin-modifying complexes with overlapping functions and components. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87: 799–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megee P. C., Morgan B. A., Smith M. M., 1995. Histone H4 and the maintenance of genome integrity. Genes Dev. 9: 1716–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M., Braberg H., Wang S., Lozsa A., Shales M., et al. , 2010. Individual lysine acetylations on the N terminus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae H2A.Z are highly but not differentially regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 39855–39865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini M. D., Wu M., Madhani H. D., 2003. Conserved histone variant H2A.Z protects euchromatin from the ectopic spread of silent heterochromatin. Cell 112: 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L., Lambert J. P., Gerdes M., Al-Madhoun A. S., Skerjanc I. S., et al. , 2008. Functional dissection of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase reveals its role as a genetic hub and that Eaf1 is essential for complex integrity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 2244–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A. J., Highland J., Krogan N. J., Arbel-Eden A., Greenblatt J. F., et al. , 2004. INO80 and gamma-H2AX interaction links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling to DNA damage repair. Cell 119: 767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichos-Chronakis M., Peterson C. L., 2013. Chromatin and the genome integrity network. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichos-Chronakis M., Watanabe S., Rando O. J., Peterson C. L., 2011. Global regulation of H2A.Z localization by the INO80 chromatin-remodeling enzyme is essential for genome integrity. Cell 144: 200–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price B. D., D’Andrea A. D., 2013. Chromatin remodeling at DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 152: 1344–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha A. J., 2004. Java Treeview: extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics 20: 3246–3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K. H., Viebranz E. B., Harris L. B., Mirzaei-Souderjani H., Syed S., et al. , 2010. Defects in DNA lesion bypass lead to spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements and increased cell death. Eukaryot. Cell 9: 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelter P., Ulrich H. D., 2003. Control of spontaneous and damage-induced mutagenesis by SUMO and ubiquitin conjugation. Nature 425: 188–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich H. D., 2007. Conservation of DNA damage tolerance pathways from yeast to humans. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35: 1334–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H., Fritsch O., Hohn B., Gasser S. M., 2004. Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 119: 777–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Chow B. L., Fontanie T., Ma L., Bacchetti S., et al. , 1999. Genetic interactions between error-prone and error-free postreplication repair pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 435: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Chow B. L., Broomfield S., Hanna M., 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD6 group is composed of an error-prone and two error-free postreplication repair pathways. Genetics 155: 1633–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G. C., Liu Y. J., Dion M. F., Slack M. D., Wu L. F., et al. , 2005. Genome-scale identification of nucleosome positions in S. cerevisiae. Science 309: 626–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.