Abstract

The Australian approach to tobacco control has been a comprehensive one, encompassing mass media campaigns, consumer information, taxation policy, access for smokers to smoking cessation advice and pharmaceutical treatments, protection from exposure to tobacco smoke and regulation of promotion. World-first legislation to standardise the packaging of tobacco was a logical next step to further reduce misleadingly reassuring promotion of a product known for the past 50 years to kill a high proportion of its long-term users. Similarly, refreshed, larger pack warnings which started appearing on packs at the end of 2012 were a logical progression of efforts to ensure that consumers are better informed about the health risks associated with smoking. Regardless of the immediate effects of legislation, further progress will continue to require a comprehensive approach to maintain momentum and ensure that government efforts on one front are not undermined by more vigorous efforts and greater investment by tobacco companies elsewhere.

Keywords: Advertising and Promotion, Packaging and Labelling, Surveillance and monitoring

A comprehensive approach

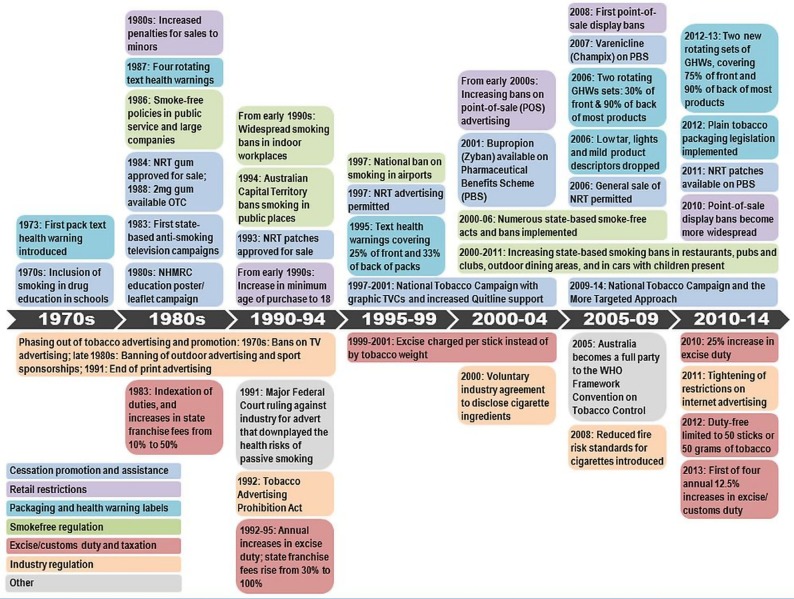

Australia was not the first country in the world to attempt to discourage smoking. It was not until 1973 that a discreet, faint gold-lettered warning about smoking being a health hazard appeared on cigarette packs,1 almost a decade after similar warnings were required in the USA.2 Televised cigarette advertisements continued until the mid-1970s, about 10 years after they had disappeared from television screens in the UK,3 the USA4 and New Zealand.5 Despite this tentative beginning, since the early 1980s Australian Governments of all persuasions have pursued the tobacco control agenda with vigour and determination. An early achiever of international best practice on many different fronts since that time, Australia was one of the first 40 countries to ratify the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC),6 and so became a full Party on 27 February 2005, the date on which the FCTC came into force. The FCTC requires Parties to adopt a systematic and broadly encompassing approach to tobacco control,6 including numerous measures to reduce the demand and supply of tobacco products. Since the early 1980s, the Australian approach to tobacco control has been just such a comprehensive one, encompassing mass media campaigns, consumer information, taxation policy, access for smokers to smoking cessation advice and pharmaceutical treatments, protection from exposure to tobacco smoke and regulation of promotion.7 The timeline depicted in figure 1 shows some of the major milestones and activities on these fronts.

Figure 1.

Timeline of major tobacco control policies in Australia, 1970s to 2014.

Source: Scollo M and Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues 2012 using material from Chapters 1, 2 3, 4, 5, 7, 11, 12A, 13, 14, 15 and 16.

Notes: Health warnings were determined at state level prior to 1996, nationally consistent by agreement. Restrictions on smoking in public places other than in aircraft and airports are covered by state legislation. Antismoking education campaigns have been run at the state level and at the national level commencing with the NHMRC poster/leaflet campaign in the early 1980s.

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; OTC, over-the-counter; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; GHW, graphic health warning.

‘Quit’ campaigns established in each state from 1983 used mass media to educate the community about the dangers of smoking.8 Government funding was secured to place advertisements during prime-time television rather than merely in late night ‘community service’ spots.9 Professional public relations activities encouraged media coverage and used celebrities and high-rating television and radio programmes to popularise the ‘Quit’ message.9 Public support for the ‘Quit’ initiative helped to encourage governments to seriously consider, and then start to enact, recommendations from international health agencies to ban all forms of promotion of tobacco products,10 and to raise taxes on tobacco products with the dual objectives of making smoking less affordable, generating additional funds for expanded public education campaigns and replacing tobacco sponsorship of sport.11

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, concerns about the health effects of exposure to other people's smoking12 saw the progressive restriction of smoking in more and more workplaces,13 14 which then generalised elsewhere.15 16 The resultant ever-expanding restrictions on smoking in hospitality venues and public places17 combined with the ever-growing evidence about the health effects and social costs of smoking, all contributed to growing antismoking sentiment. Antismoking norms have been demonstrated to have a profound effect on the frequency18 and uptake of smoking.19

Sustained investment yields results

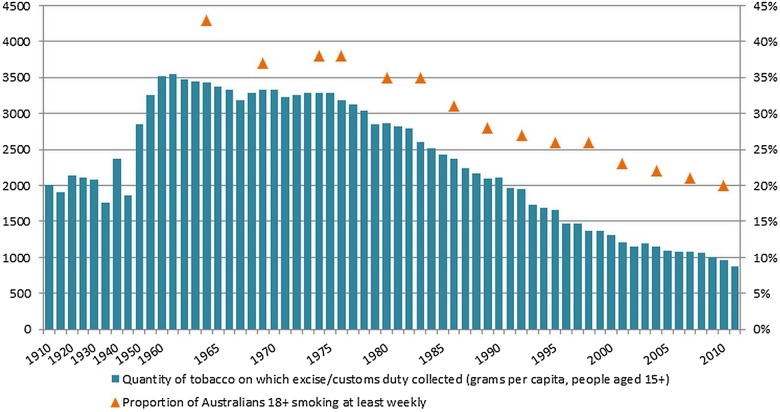

Over the past four decades of intense activity, consumption of tobacco products declined substantially in Australia, reducing from a high of more than 3500 g of tobacco per person (15 years and older) in 1961 to less than an estimated 875 g per capita in recent years (see figure 2). Prevalence of smoking has also declined substantially.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of smoking and per capita consumption of tobacco products, Australia 1910 to 1960 (5-yearly), 1960 to 2011.

Source: Scollo M. Figure I.2 Major tobacco promotion and tobacco control policies and regular smoking & per capita consumption of tobacco products, Australia 1910 to 1960 (5-yrly), 1960 to 2010 in Introduction. Scollo M and Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues 2012.

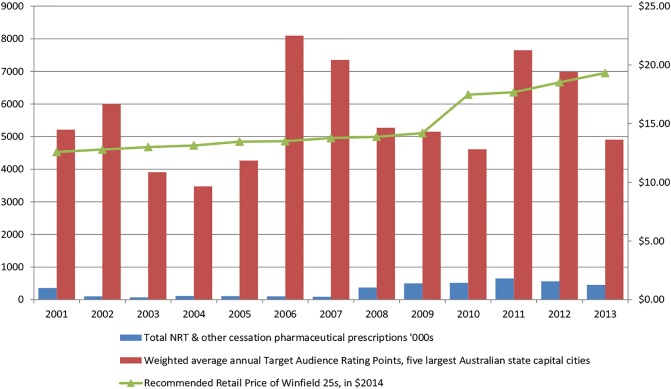

A stall in the decline in prevalence occurred in the mid-1990s, corresponding with reduced expenditure on public campaigns20 and less media interest following a decade of intense political campaigning; however, a major injection of funds through the National Tobacco Campaign in 199721–23 kick-started the decline again in that year.24–26 Campaigns over the late 2000s were funded at more commercially realistic levels in most states. This has allowed Australian smokers to be consistently exposed to television advertisements about the health effects of smoking (see figure 3 for an indication of the annual reach and frequency of that advertising in Australia since 2001).

Figure 3.

Affordability of tobacco and investment in tobacco control in Australia—media TARPs, recommended price of Winfield 25s (leading Australian brand) and number of prescriptions for pharmaceutical treatments, 2001 to 2013.

Sources: TARPs* Metropolitan TV Monthly TARP Flighter data, 2001–2013. Prepared for Cancer Council Victoria. Macquarie Park, Australia: Nielsen Company Pty Ltd. Prices Australian Retail Tobacconist August editions, 2001 to 2013. Prescriptions Health Insurance Commission, Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule Item reports for nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline. https://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics/pbs_item.shtml

*Note: TARPs are a product of the percentage of the target audience (aged 18+ years) potentially exposed to an advertisement (reach) and the average number of times the target audience is exposed (frequency). 1000 TARPs represents 100% of the target audience receiving 10 advertisements per year, or 50% receiving 20 advertisements per year.

NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; TARP, Target Audience Rating Points.

Tax policy has always been a crucial part of Australia's comprehensive approach to discouraging smoking.27 28 Frequent increases in state fees on tobacco from the early 1980s until their abolition in 1997 carried through to frequent increases in the price of tobacco products, though the effects were somewhat blunted by tobacco companies’ development of large pack sizes which attracted much less tax than smaller packs. The tax on large packets of cigarettes increased substantially following tax reforms adopted in 1999, with further increases associated with the implementation of Australia's Goods and Services Tax in 2000–2001.29 Taxes increased again substantially in April 2010,30 December 2013 and September 2014, with further increases scheduled for September 2015 and 2016. The recommended retail price over time of Winfield 25s, Australia's leading brand,31 is shown in figure 3.

Consistent with a long-standing commitment to a comprehensive approach, Australian governments have not relied on tax alone. A variety of telephone, internet, SMS programmes and smartphone applications have been put in place across the country to support and encourage smokers in their quit attempts. Smoking cessation aids were listed on the national Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in 2001 (bupropion), 2008 (varenicline) and 2011 (nicotine replacement therapies, extended from subsidies limited to war veterans and Indigenous smokers to all Australian smokers). Since 2001, almost three million prescriptions for treatments have been dispensed (see blue bars in figure 3).

Recent initiatives

The social costs of smoking and the case for investment in smoking cessation and tobacco control more generally have been widely accepted in Australia since the late 1990s.32 33 Faced with an ageing cohort of postwar baby boomers and the prospect of a shrinking workforce to support rising healthcare costs, recent Australian governments have looked to tobacco control for continuing returns for their investment in disease prevention. In 2008 and then again in 2012, all governments in Australia—state, territory and federal—signed a national healthcare agreement34 with the ambitious goal of reducing adult daily smoking prevalence to 10% and halving the adult daily smoking rate among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders by 2018 (clause 18.3).35 In May 2010, the Government released its response to a far-reaching and detailed set of recommendations formulated by a national taskforce on preventive health.36 This document affirmed the Government's intention to implement plain packaging and an immediate 25% increase in customs/excise duty on tobacco (announced on the 29 April 2010—see Scollo et al (this volume) for a timeline of events).37 The response document also outlined the Government's commitment to adopting numerous other recommended measures including enlarged graphic health warnings, tightening of restrictions on advertising of tobacco products in particular on the internet, increased funding for mass media campaigns and additional programmes for Indigenous smokers and people living with mental illness. In 2012 the Australian Government and state and territory governments approved a new national tobacco strategy, the NTS 2012–2018,38 which is much more far-reaching than its predecessors39–41 and aims to strengthen and extend activities in all the major streams of tobacco control over the 6 years to 2018.

Tobacco plain packaging—a logical progression

Australia has been described by the tobacco industry as the world's ‘darkest market’.42 Tobacco advertising has been banned in virtually every form of media—on TV and radio through the 1970s, on billboards and outside shops during the 1980s, in the print media and through sports sponsorship during the 1990s and at point of sale from the early 2000s, with retail display of products banned altogether in most states from about 2010.43 By the mid-2000s, attractive design of packs was one of the few ways that Australian tobacco companies could continue to promote their products. World-first legislation to standardise the packaging of tobacco44 was both a response to this marketing strategy and a logical next step to further reduce the misleadingly reassuring promotion of a product known to cause the death of more than half of its long-term users.45

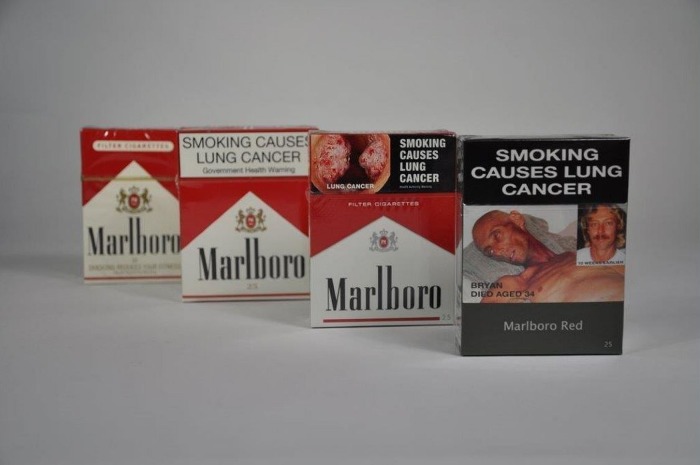

Enlarged graphic health warnings—another logical progression

In addition to some of the earliest and strongest television-led antismoking campaigns,8 clear and direct information for tobacco consumers on product packaging has also been an important part of the Australian approach, with four rotating warnings introduced on cigarette packs in 19871 and bold text warnings in 1995.46 47 Australia was one of the first countries in the world to follow Canada's lead with graphic health warnings complemented by comprehensive back-of-pack information explicating the warning statement implemented in 2006.48 Once again, the refreshed, larger pack warnings which started appearing on packs at the end of 201249 were a logical progression of efforts to ensure that consumers are better informed about the health risks associated with smoking (see figure 4).

Figure 4.

Marlboro cigarettes displaying changing consumer product information—as they appeared in Australia from 1987 (rear), the late 1990s, the late 2000s (second from front) and from December 2012 after the introduction of plain packaging (front).

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection.

Evaluating impact

The decline in smoking in Australia since the late 1990s resulted from more people quitting, and fewer young people taking up smoking.50–52 In line with the findings of research throughout the rest of the world,53 studies measuring short-term effects have been able to attribute reductions in smoking prevalence in Australia to increasing taxes,27 28 greater expenditure on social marketing campaigns27 28 54 55 and smoke-free policies.28 56 Multivariate analysis of the effects of policy on prevalence of smoking among adolescents in various Australian states from 1990 to 2005 also indicates strong effects for increases in the price of tobacco products, expenditure on social marketing and comprehensiveness of smoke-free policies in public places.57 However, such studies tell only part of the story.

As illustrated in US Surgeon General's reports, which have exhaustively reviewed the evidence about the effectiveness of tobacco control over the past five decades,58 59 smoking is a multi-factorial problem—a tug-of-war between the forces which promote and facilitate the use of tobacco products and the forces which discourage and inhibit its use; a tug-of-war played out at the individual, household and community levels as well as in the wider culture. Each of the regulatory, educational and clinical factors highlighted in figure 1 vary widely in their techniques and effects, some of which are contributory rather than independent,58 and difficult to capture at the population level through standard statistical analysis.60–63 However, it seems likely that each would have contributed in some way to reduce tobacco smoking—either directly or indirectly—by having: reduced the glamour and appeal of tobacco products; increased knowledge about health effects; reduced cues and opportunities for smoking; reduced the social acceptability and other rewards of smoking and increased its costs; increased smokers’ knowledge about how to manage the quitting process; or reduced withdrawal symptoms during quitting.

The studies in this volume examine the impact of Australia's tobacco plain packaging legislation and the simultaneously introduced enlarged graphic health warnings37 not on smoking prevalence, which is affected by a variety of demographic, marketing and policy factors over time, but rather on the perceived appeal of tobacco packaging, the effectiveness of health warnings and consumer misperceptions of harm.64–66 67 Downstream effects on attitudes, beliefs and intentions are also examined,68 69 as are tobacco industry claims about possible and unintended consequences.70–73 Regardless of the immediate effects, further progress in Australia will continue to require a comprehensive approach to maintain momentum and ensure that government efforts on one front are not undermined by more vigorous efforts and greater investment by tobacco companies elsewhere.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this topic

Australia has been an early achiever on many different fronts in tobacco control.

It was the first country in the world to standardise the packaging of tobacco products.

What this paper adds

This paper provides a brief history of Australia's comprehensive approach to tobacco control and explains the rationale for adoption of plain packaging legislation and enhanced graphic health warnings.

Footnotes

Contributors: MW and MS conceived of this paper. MS and MB coordinated collection of data and undertook data analysis. MS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to the finalisation of the manuscript.

Funding: Production of this paper was supported by Cancer Council Victoria.

Competing interests: The authors wish to advise that MS was a technical writer for and MW a member of the Tobacco Working Group of the Australian National Preventive Health Task Force and MW was a member of the Expert Advisory Committee on Plain Packaging that advised the Australian Department of Health on research pertaining to the plain packaging legislation. MW holds competitive grant funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, US National Institutes of Health, Australian National Preventive Health Agency and BUPA Health Foundation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Scollo M. Chapter 12.1 Health warnings. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, 2013. http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/a12-1-1-history-health-warnings [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centres for Disease Control. Selected actions of the U.S. Government regarding the regulation of tobacco sales, marketing, and use (excluding laws pertaining to agriculture or excise tax). Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2012. [updated 15 Nov 2012; Aug 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/by_topic/policy/legislation/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. Television Act, 1964, (1964). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1964/26.

- 4. Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act, (1969). http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/15/1331.

- 5.The Smokefree Coalition. The history of tobacco control in New Zealand 2012. http://www.sfc.org.nz/infohistory.php

- 6.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. New York: United Nations, 2003. 2302. http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scollo M, Winstanley M. Introduction. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Quit Victoria, 2012. http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce J, Dwyer T, Frape G, et al. Evaluation of the Sydney ‘Quit For Life’ anti-smoking campaign. Part 1. Achievement of intermediate goals. Med J Aust 1986;144:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer. Quit evaluation studies. Melbourne: Victorian Smoking and Health Program, 1985 to 2001. http://www.quit.org.au/browse.asp?ContainerID=1755 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powles JW, Gifford S. Health of nations: lessons from Victoria, Australia. Br Med J 1993;306:125–6. 10.1136/bmj.306.6870.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borland R, Winstanley M, Reading D. Legislation to institutionalize resources for tobacco control: the 1987 Victorian Tobacco Act. Addiction 2009;104:1623–9. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makkai T, McAllister I. Public opinion towards drug policies in Australia 1985 to 95. Canberra: Australian Government, 1998. http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/previous20series/other/21-40/public20opinion20towards20drug20policies20in20australia201985-95.html [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakefield M, Roberts L, Owen N. Trends in prevalence and acceptance of workplace smoking bans among indoor workers in South Australia. Tob Control 1996;5:205–8. 10.1136/tc.5.3.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borland R, Morand M, Mullins R. Prevalence of workplace smoking bans in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health 1997;21:694–8. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1997.tb01782.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh R, Tzelepis F. Support for smoking restrictions in bars and gaming areas: review of Australian studies. Aust N Z J Public Health 2003;27:310–22. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh R, Tzelepis F, Paul C, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke in homes, motor vehicles and licensed premises: community attitudes and practices. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26:536–42. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merom D, Rissel C. Factors associated with smoke-free homes in NSW: results from the 1998 NSW Health Survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:339–45. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alamar B, Glantz S. Effect of increased social unacceptability of cigarette smoking on reduction in cigarette consumption. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1359–63. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Mathios A, et al. Youth smoking, cigarette prices, and anti-smoking sentiment. Health Econ 2008;17:733–49. 10.1002/hec.1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill DJ, White VM, Scollo MM. Smoking behaviours of Australian adults in 1995: trends and concerns. Med J Aust 1998;168:209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill D, Alcock J. Background to campaign. In: Hassard K, ed. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report. Vol 1 Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-metadata-tobccamp.htm [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill D, Borland R, Carroll T, et al. Perspectives of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign. In: Hassard K, ed. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report. Vol 2 Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000:1–9. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-tobccamp_2-cnt.htm [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill D, Carroll T. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control 2003;12:ii9–14. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakefield M, Freeman J, Boulter J. Changes associated with the National Tobacco Campaign: pre and post campaign surveys compared. In: Hassard K, ed. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report. Vol 1 Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-metadata-tobccamp.htm [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan N, Wakefield M, Freeman J. Changes associated with the National Tobacco Campaign: results of the second follow-up survey. In: Hassard K, ed. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report. Vol 2 Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000:21–75. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-tobccamp_2-cnt.htm [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakefield M, Freeman J, Inglis G. Ch 5 Changes associated with the National Tobacco Campaign: results of the third and fourth follow-up surveys. In: Hassard K, ed. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign; evaluation report. Vol 3 Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2004. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-tobccamp_3-cnt [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakefield M, Durkin S, Spittal M, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on monthly adult smoking prevalence: time series analysis. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1443–50. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakefield MA, Coomber K, Durkin SJ, et al. Time series analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence among Australian adults, 2001–2011. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:413–22. 10.2471/BLT.13.118448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scollo M, Younie S, Wakefield M, et al. Impact of tobacco tax reforms on tobacco prices and tobacco use in Australia. Tob Control 2003;12:ii59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudd K, Swan W, Roxon N. Minister, Treasurer, Minister for Health. Anti-Smoking Action. Canberra 29 April 2010. Available from: http://pmtranscripts.dpmc.gov.au/browse.php?did=17255 [Google Scholar]

- 31.NSW Retail Tobacco Traders’ Association. Cigarette price lists. Australian Retail Tobacconist 2001 to 2013;60 to 69.

- 32.Abelson P. Applied Economics. Returns on investment in public health. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2003. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-roi_eea-cnt.htm [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurley S. Chapter 17. The economics of tobacco control. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, eds. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, 2013. http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-17-economics [Google Scholar]

- 34.COAG Reform Council. National Healthcare Agreement: baseline performance report for 2008–09. Sydney: COAG Reform Council, 2010. http://www.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/content/national_agreements.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 35. Excise Tariff Amendment (Tobacco) Act 2014, Stat. No 9 (2014). http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2014A00009.

- 36.Australian Government. Taking preventative action: government's response to Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2010. http://yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/Content/report-preventativehealthcare [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scollo M, Lindorff K, Coomber K, et al. Standardised packaging and new enlarged graphic health warnings for tobacco products in Australia—legislative requirements and implementation of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 and the Competition and Consumer (Tobacco) Information Standard, 2011. Tob Control 2015;24:ii9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Intergovernmental Committee on Drugs Standing Committee on Tobacco. National Tobacco Strategy 2012–2018. Canberra: Australian Government, 2013. http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/national_ts_2012_2018 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health. National Health Policy on Tobacco in Australia and examples of strategies for implementation. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health, 1991. 1 p. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Expert Advisory Committee on Tobacco. National Tobacco Strategy 1999 to 2002–03, prepared for the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Services, 1999. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/Publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-metadata-tobccstrat.htm [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. Australian National Tobacco Strategy 2004–2009. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2005. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/tobacco-strat [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter SM. Going below the line: creating transportable brands for Australia's dark market. Tob Control 2003;12:iii87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman B. Chapter 11. Advertising and promotion of tobacco. In: Scollo M, ed. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria, 2013. http://www.TobaccoInAustralia.org.au [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tobacco Plain Packaging Act. http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2011A00148.

- 45.Preventative Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. National Preventative Health Strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. http://www.preventativehealth.org.au/internet/preventativehealth/publishing.nsf/Content/national-preventative-health-strategy-1lp [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trade Practices (Consumer Product Information Standards) (Tobacco) Regulations—repealed, 83 and 408 (1994 (Cth)). http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/num_reg/tppisr1994n83741/

- 47.Borland R, Hill D. The path to Australia's tobacco health warnings. Addiction 1997;92:1151–7. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Trade Practices (Consumer Product Information Standards) (Tobacco) Regulations 2004, no.264 (2004 (Cth)). http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/num_reg/tppisr20042004n264741/

- 49. Competition and Consumer (Tobacco) Information Standard,—F2011L02766 (2011). http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2011L02766.

- 50.Australian Data Archive Social Sciences collection. National Drug Strategy Household Survey, 2010 [database on the internet]. Australian National University 2011. [cited Dec 2011]. http://www.ada.edu.au/social-science/01237

- 51.Germain D, Durkin S, Scollo M, et al. The long-term decline of adult tobacco use in Victoria: changes in smoking initiation and quitting over a quarter of a century of tobacco control. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012;36:17–23. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Highlights from the 2013 survey: tobacco smoking. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. [updated 27 Jul; AIHW cat. no. PHE 145]. http://www.aihw.gov.au/alcohol-and-other-drugs/ndshs/2013/data-and-references/ [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson LM, Avila Tang E, Chander G, et al. Impact of tobacco control interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: a systematic review. J Environ Public Health 2012;2012:961724 10.1155/2012/961724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control 2012;21:127–38. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Cancer Institute. Part 4—Tobacco control and media interventions. The Role of the Media. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph no. 19. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2008. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/tcrb/monographs/19/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 56.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies. Lyon, France: IARC, 2009. 13. http://com.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/prev/handbook13/ [Google Scholar]

- 57.White V, Warne C, Spittal M, et al. What impact have tobacco control policies, cigarette price and tobacco control program funding had on Australian adolescents’ smoking? Findings over a 15-year period. Addiction 2011;106:1493–502. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.US Department of Health and Human Services. Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2000. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2000/complete_report/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 59.US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2012/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chapman S. Commentary: if you can't count it...it doesn't count: the poverty of econometrics in explaining complex social and behavioural change. Health Promot J Austr 1999;9:206–7. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borland R. On apparent consumption and what goes up in smoke: a commentary on Bardsley & Olekalns. Health Promot J Austr 1999;9:208–9. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bardsley P, Olekalns N. The impact of anti-smoking policies on tobacco consumption in Australia. Health Promot J Austr 1999;9:202–5. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chapman S. Unravelling gossamer with boxing gloves: problems in explaining the decline in smoking. BMJ 1993;307:429–32. 10.1136/bmj.307.6901.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wakefield M, Coomber K, Zacher M, et al. Australian adult smokers’ responses to plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings 1 year after implementation: results from a national cross-sectional tracking survey. Tob Control 2015;24:ii17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White V, Williams T, Faulkner A, et al. Do larger graphic health warnings on standardised cigarette packs increase adolescents' cognitive processing of consumer health information and beliefs about smoking-related harms? Tob Control 2015;24:ii50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White V, Williams T, Wakefield M, et al. Has the introduction of plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings changed adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette packs and brands? Tob Control 2015;24:ii42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller C, Ettridge KA, Wakefield MA. “You're made to feel like a dirty filthy smoker when you're not, cigar smoking is another thing all together.” Responses of Australian cigar and cigarillo smokers to plain packaging. Tob Control 2015;24:ii58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brennan E, Durkin S, Coomber K, et al. Are quitting-related cognitions and behaviours predicted by proximal responses to plain packaging with larger health warnings? Findings from a national cohort study with Australian adult smokers. Tob Control 2015;24:ii33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Durkin S, Brennan E, Coomber K, et al. Short-term changes in quitting-related cognitions and behaviours after the implementation of plain packaging with larger health warnings: findings from a national cohort study with Australian adult smokers. Tob Control 2015;24:ii26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scollo M, Bayly M, Wakefield M. Did the recommended retail price of tobacco products fall in Australia following the implementation of plain packaging? Tob Control 2015;24:ii90-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scollo M, Bayly M, Wakefield M. The advertised price of cigarette packs in retail outlets across Australia before and after the implementation of plain packaging: a repeated measures observational study. Tob Control 2015;24:ii82–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Scollo M, Zacher M, Coomber K, et al. Changes in use of types of tobacco products by pack sizes and price segments, prices paid and consumption following the introduction of plain packaging in Australia. Tob Control 2015;24:ii66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scollo M, Zacher M, Coomber K, et al. Use of illicit tobacco following introduction of standardised packaging of tobacco products in Australia: results from a national cross-sectional survey. Tob Control 2015;24:ii76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]